wild rhododendrons

EXPLORATION, SETTLEMENT, AND GROWTH

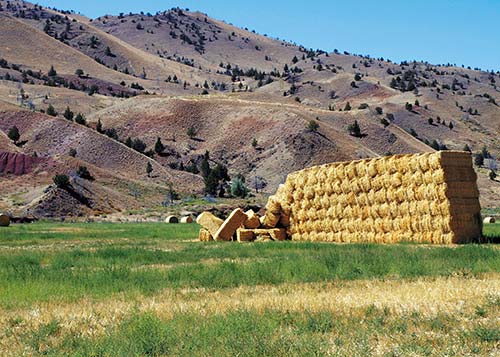

northeastern Oregon, where ranching and farming are important.

If Oregon were part of a jigsaw puzzle of the United States, it would be a squarish piece with a divot carved out of the center top. To the west is the Pacific Ocean, with some 370 miles of beaches, dunes, and headlands; to the east are the Snake River and Idaho. Up north, much of the boundary between Oregon and Washington is defined by the mighty Columbia River, while southern Oregon lies atop the upper borders of California and Nevada.

Moving west to east, the major mountain systems start with the Klamath Mountains and the Coast Range. The Klamaths form the lower quarter of the state’s western barrier to the Pacific; the eastern flank of this range is generally referred to as the Siskiyous. To the north, the Oregon Coast Range, a younger volcanic range, runs north-south in parallel to the coastline. The highest peaks in each of these cordilleras barely top 4,000 feet and stand between narrow coastal plateaus on the west side and the rich agricultural lands of the Willamette and Rogue Valleys on the other. Running up the west-central portion of the state is the Cascade Range, which extends from northern California to Canada. Five of the dormant volcanoes in Oregon top 10,000 feet above sea level, with Mount Hood, the state’s highest peak, at 11,239 feet.

Beyond the eastern slope of the Cascades, semiarid high-desert conditions begin. In the northeast, the 10,000-foot crests of the snowcapped Wallowas rise less than 50 miles away from the hot, arid floor of Hells Canyon, itself about 1,300 feet above sea level. The Great Basin desert—characterized by rivers that evaporate, peter out, or disappear underground—makes up the bottom corner of eastern Oregon. Here the seven-inch annual rainfall of the Alvord Desert seems as if it would be more at home in Nevada than in a state known for blustery rainstorms and lush greenery. In addition to Hells Canyon, the country’s deepest hole in the ground (7,900 feet maximum depth), Oregon also boasts the continent’s deepest lake: Crater Lake, with a depth of 1,958 feet.

Each part of the state contains well-known remnants of Oregon’s cataclysmic past. Offshore waters here feature 1,477 islands and islets, the eroded remains of ancient volcanic flows. Lava fields dot the approaches to the High Cascades. East of the range, a volcanic plateau supports cinder cones, lava caves, and lava-cast forests in the most varied array of these phenomena outside Hawaii.

Erosion has exposed many volcanic curiosities in eastern Oregon.

The imposing volcanic cones of the Cascades and the inundated caldera that is Crater Lake, formed by the implosion of Mount Mazama 6,600 years ago, are some of the most dramatic reminders of Oregon’s volcanic origins. More fascinating evidence can be seen up close at Newberry National Volcanic Monument, an extensive area south of Bend that encompasses obsidian fields and lava formations left by massive eruptions. (Geologists have cited Newberry on their list of volcanoes in the continental United States most likely to erupt again.) Not far from the Lava Lands Visitors Center in the national monument are the Lava River Cave and Lava Cast Forest—created when lava enveloped living trees 6,000 years ago.

Scientists exploring Tillamook County in 1990 unearthed discontinuities in both rock strata and tree rings, indicating that the north Oregon coast has experienced major earthquakes every several hundred years. They estimate that the next one could come within the next 50 years and be of significant magnitude. With virtually every part of the state possessing seismic potential that hasn’t been released in many years, the pressure along the fault lines is increasing.

In coastal areas, one of the greatest dangers associated with earthquakes is the possibility of tsunamis. When the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake hit Japan, Oregon’s coastal residents fled to higher ground; although most of the state’s coast was spared, eight-foot waves along the southern coast damaged the harbor in Brookings.

However pervasive the effects of seismic activity and volcanism are, they must still share top billing with the last ice age in the grand epic of Oregon’s topography. At the height of the most recent major ice age glaciation, the world’s oceans were 300 to 500 feet lower, North America and Asia were connected by a land bridge across the Bering Strait, and the Oregon coast was miles west of where it is today. The Columbia Gorge extended out past present-day Astoria. As the glaciers melted, the sea rose.

When that glacial epoch’s final meltdown 12,000 years ago unleashed water dammed up by thousands of feet of ice, great rivers were spawned and existing channels enlarged. A particularly large inundation was the Missoula Floods, which began as ice dams broke up in what’s now northern Idaho and western Montana, releasing epic floods of glacial meltwater. These floodwaters carved out the contours of what are now the Columbia River Gorge and the Willamette Valley.

Oregon’s location equidistant from the equator and the north pole subjects it to weather from both tropical and polar airflows. This makes for a pattern of changeability in which calm often alternates with storm, and extreme heat and extreme cold seldom last long.

Oregon’s weather is best understood as a series of valley climates separated from each other by mountain ranges that draw precipitation from the eastbound weather systems. Moving west to east, each of these valley zones receives progressively lower rainfall level, culminating in the desert on the eastern side of the state.

Wet but mild, average rainfall on the coast ranges from a low of 64 inches per year in the Coos Bay area to nearly 100 inches around Lincoln City. The Pacific Ocean moderates coastal weather year-round, softening the extremes. Spring, summer, and fall generally don’t get very hot, with highs generally in the 60s and 70s and seldom topping 90°F. Winter temperatures only drop to the 40s and 50s, and freezes and snowfall are quite rare.

If there is one constant in western Oregon, it is cloudiness. Portland and the Willamette Valley receive only about 45 percent of maximum potential sunshine; more than 200 days of the year are cloudy, and rain falls an average of 150 days. While this might sound bleak, consider that the cloud cover helps moderate the climate by trapping and reflecting the earth’s heat. On average, fewer than 30 days of the year record temperatures below freezing. Except in mountainous areas, snow usually isn’t a force to be reckoned with. Another surprise is that Portland’s average annual rainfall of 40 inches is usually less than totals recorded in New York City, Miami, or Chicago. In the southern valleys, Ashland and Medford typically record only half the yearly precipitation of their neighbors to the north, as well as higher winter and summer temperatures.

The landscape of central and eastern Oregon by and large determines the weather, but you can almost always count on weather out here to be more extreme than in western Oregon. In summer, mountainous areas will be cooler, while the extensive desert basins of eastern Oregon can be scorching. Winter can bring snow and cold temperatures across the entire region.

With 4,400 known species and varieties, Oregon ranks fourth among U.S. states for plant diversity, including dozens of species found nowhere else.

The mixed-conifer ecosystem of western Oregon—dense, far-reaching forests of Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock interspersed with bigleaf maple, vine maple, and alder—is among the most productive woodlands in the world. In southern Oregon, you’ll find redwood groves and rare myrtle trees, prized by woodworkers for their distinctive coloring and grain, while huge ponderosa pines are a hallmark of central and eastern Oregon. A particularly striking autumnal display along the McKenzie River mixes red vine maple and sumacs with golden oaks and alders against an evergreen backdrop.

Of the 19 million acres of old growth that once proliferated in Oregon and Washington, less than 10 percent survive. Naturalists describe an old-growth forest as a mixture of trees, some of which must be at least 200 years old, and a supply of snags or standing dead trees, nurse logs, and streams with downed logs. Of all the old-growth forests mentioned in this volume, Opal Creek in the Willamette Valley most spectacularly embodies all of these characteristics.

While giant conifers and a profuse understory of greenery predominate coastal forests, this ecosystem represents only the most visible part of the Oregon coast’s bountiful botany. Many coastal travelers will notice European beachgrass (Ammophila arenaria) covering the sand wherever they go. Originally planted in the 1930s to inhibit dune growth, the thick, rapidly spreading grass worked too well, solidifying into a ridge behind the shoreline, blocking the windblown sand from replenishing the rest of the beach, and suppressing native plants.

Freshwater wetlands and bogs, created where water is trapped by the sprawling sand dunes along the central coast, provide habitats for some unusual species. Best known among these is the cobra lily (Darlingtonia californica), which can be viewed up close just north of Florence. Also called pitcher plant, this carnivorous bog dweller survives on hapless insects lured into a specialized chamber, where they are trapped and digested.

trillium in Portland’s Forest Park

Coastal salt marshes, occurring in the upper intertidal zones of coastal bays and estuaries, have been dramatically reduced due to land “reclamation” projects such as drainage, diking, and other human disturbances. The halophytes (salt-loving plants) that thrive in this specialized environment include pickleweed, saltgrass, fleshy jaumea, salt marsh dodder, arrowgrass, sand spurrey, and seaside plantain. Coastal forests include Sitka spruce and alder riparian communities, which provide resting and feeding areas for migratory waterfowl, shore and wading birds, and raptors.

While not as visually arresting as the evergreens of western Oregon, the state’s several varieties of berries are no less pervasive. Found mostly from the coast to the mid-Cascades, invasive Himalayan blackberries favor clearings, burned-over areas, and people’s gardens. They also take root in the woods alongside wild strawberries, salmonberries, thimbleberries, currants, and salal. Within this edible realm, wild-food connoisseurs especially seek out the thin-leafed huckleberry found in the Wallowa, Blue, Cascade, and Klamath Ranges. Prime snacking season for all these berries ranges from midsummer to mid-fall.

No less prized are the rare plant communities of the Columbia River Gorge and the Klamath-Siskiyou region. A quarter of Oregon’s rare and endangered plants are found in the latter area, a portion of which is in the valley of the Illinois River, a designated Wild and Scenic tributary of the Rogue. Kalmiopsis leachiana, a rare member of the heath family endemic to southwestern Oregon, even has a wilderness area named after it.

Motorists will treasure such springtime floral fantasias (both wild and domesticated) such as the dahlias and irises near Canby off I-5; tulips near Woodburn; irises off Highway 213 outside Salem; the Easter lilies along U.S. 101 near Brookings; blue lupines alongside U.S. 97 in central Oregon; apple blossoms in the Hood River Valley near the Columbia Gorge; pear blossoms in the Bear Creek Valley near Medford; bear grass, columbines, and Indian paintbrush on Cascades thoroughfares; and rhododendrons and fireweed along the coast.

East of the Cascades, the undergrowth is often more varied than the ground cover in the damp forests on the west side of the mountains. This is because sunny openings in the forest permit room for more species and for plants of different heights. And, in contrast to the white flowers that predominate in the shady forests in western Oregon, “dry-side” wildflowers generally have brighter colors. These blossoms attract color-sensitive pollinators such as bees and butterflies. On the opposite flank of the range, the commonly seen white trillium relies on beetles and ants for propagation, lessening the need for eye-catching pigments.

Autumn is the season for those who covet wild chanterelle and matsutake mushrooms. September through November, the Coast Range is the prime picking area for chanterelles—a fluted orange or yellow mushroom in the tall second-growth Douglas fir forests. In the spring, fungus-lovers’ hearts turn to morels. Of course, you should be absolutely certain of what you have before you eat wild mushrooms, or any other wild food. Farmers markets are usually good places to find an assortment of wild mushrooms.

Oregon’s creatures great and small are an excitingly diverse group. Oregon’s relatively low population density, abundance of wildlife refuges and nature preserves, and biomes running the gamut from rainforest to desert explain this variety. Throughout the state, numerous refuges, such as the South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, the Jewell Meadows Wildlife Area preserve for Roosevelt elk, and the Finley National Wildlife Refuge provide safe havens for both feathered and furry friends.

For many visitors, the most fascinating coastal ecosystems in Oregon are the rocky tide pools. These Technicolor windows offer an up-close look at one of the richest—and harshest—environments, the intertidal zone, where pummeling surf, unflinching sun, predators, and the cycle of tides demand tenacity and special adaptation.

The natural zone where surf meets shore is divided into three main habitat layers, based on their position relative to tide levels. The high intertidal zone, inundated only during the highest tides, is home to creatures that can either move, such as crabs, or are well adapted to tolerate daily desiccation, such as acorn barnacles and finger limpets, chitons, and green algae. The turbulent mid-intertidal zone is covered and uncovered by the tides, usually twice each day. In the upper portion of this zone, California mussels and goose barnacles may thickly blanket the rocks, while ochre sea stars and green sea anemones are common lower down, along with sea lettuce, sea palms, snails, sponges, and whelks. Below that, the low intertidal zone is exposed only during the lowest tides. Because it is covered by water most of the time, this zone has the greatest diversity of organisms in the tidal area. Residents include many of the organisms found in the higher zones, as well as sculpins, abalone, and purple sea urchins.

Standout destinations for exploring tide pools include Cape Arago, Cape Perpetua, the Marine Gardens at Devil’s Punchbowl, and beaches south and north of Gold Beach, among many others. Tide pool explorers should be mindful that, despite the fact that the plants and animals in the pools are well adapted to withstand the elements, they and their ecosystem are actually quite fragile, and they’re very sensitive to human interference. Avoid stepping on mussels, anemones, and barnacles, and take nothing from the tide pools. In the Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge and other specially protected areas, removal or harassment of any living organism may be treated as a misdemeanor punishable by fines.

Few sights along the Oregon coast elicit more excitement than that of a surfacing whale. The most common large whale seen from shore along the West Coast of North America is the gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus). These behemoths can reach 45 feet in length and 35 tons in weight. The sight of a mammal as big as a Greyhound bus erupting from the sea has a way of emptying the mind of mundane concerns. Wreathed in seaweed and sporting barnacles and other parasites on its back, a California gray whale might look more like the hull of an old ship were it not for its expressive eyes.

Some gray whales are found off the Oregon coast all year, including an estimated 200-400 during the summer, though they’re most visible and numerous when migrating populations pass through Oregon waters on their way south December-February and northward early March-April. This annual journey from the rich feeding grounds of the Bering and Chukchi Seas of Alaska to the calving grounds of Mexico amounts to some 10,000 miles, the longest migration of any mammal. On the Oregon coast, their numbers peak usually during the first week of January, when as many as 30 per hour may pass a given point. By mid-February, most of the whales will have moved on toward their breeding and calving lagoons on the west coast of Baja California.

Early March-April, the juveniles, adult males, and females without calves begin returning northward past the Oregon coast. Mothers and their new calves are the last to leave Mexico and move more slowly, passing Oregon late April-June. During the spring migration, the whales may pass within just a few hundred yards of coastal headlands, making this a particularly exciting time for whale-watching from any number of vantage points along the coast.

Pacific harbor seals, California sea lions, and Steller sea lions are frequently sighted in Oregon waters. California sea lions are characterized by their 1,000-pound size and their small earflaps, which seals lack. Unlike seals, they can point their rear flippers forward to give them better mobility on land. Lacking the dense underfur that covers seals, sea lions tend to prefer warmer waters.

With warming oceans, sea lions are more numerous than ever in Oregon.

Steller sea lions can be seen at the Sea Lion Caves. They also breed on reefs off Gold Beach and Port Orford. In the largest sea lion species, males can weigh more than a ton. Their coats tend to be gray rather than the nearly black California sea lions. They also differ from their California counterparts in that they are comfortable in colder water.

Look for Pacific harbor seals in bays and estuaries up and down the coast, sometimes miles inland. They’re nonmigratory, have no earflaps, and can be distinguished from sea lions because they’re much smaller (150-300 pounds) and have mottled fur that ranges in color from pale cream to rusty brown.

In recent decades, dwindling Pacific salmon and steelhead stocks have prompted restrictions on commercial and recreational fishing in order to restore threatened and endangered species throughout the Pacific Northwest. Runs are highly variable from year to year; for more information about fish populations and fishing restrictions, see the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s website (www.dfw.state.or.us).

The salmon’s life cycle begins and ends in a freshwater stream. After an upriver journey from the sea of sometimes hundreds of miles, the spawning female deposits 3,000-7,000 eggs in hollows (called redds) she has scooped out of the coarse sand or gravel, where the male fertilizes them. These adult salmon die soon after mating, and their bodies then deteriorate to become part of the food chain for young fish.

Within three or four months, the eggs hatch into alevin, tiny immature fish with their yolk sac still attached. As the alevin exhaust the nutrients in the sac, they enter the fry stage, and begin to resemble very small salmon. The length they remain as fry differs among various species. Chinook fry, for example, immediately start heading for saltwater, whereas coho or silver salmon will remain in their home stream for one to three years before moving downstream. The salmon are in the smolt stage when they start to enter saltwater. The five- to seven-inch smolts will spend some time in the estuary area of the river or stream while they feed and adjust to the saltwater.

When it finally enters the ocean, the salmon is considered an adult. Each species varies in the number of years it remains away from its natal stream, foraging sometimes thousands of miles throughout the Pacific. Chinook can spend as many as seven years away from their nesting (and ultimately their resting) place; most other species remain in the salt for two to four years. Spring and fall mark the main upstream runs of the Pacific salmon. It is thought that young salmon imprint the odor of their birth stream, enabling them to find their way home years later.

The salmon’s traditional predators such as the sea lion, northern pikeminnow, harbor seal, black bear, Caspian tern, and herring gull pale in comparison to the threats posed by modern civilization. Everything from pesticides to sewage to nuclear waste has polluted Oregon waters, and until mitigation efforts were enacted, dams and hydroelectric turbines threatened to block Oregon’s all-important Columbia River spawning route.

Oregon is home to cougars, also known as mountain lions. As human development encroaches on their territory, sightings of these large cats become more common. Although they tend to shy away from big people, they’ve been known to attack children and small adults. For this reason, if no other, keep your kids close to the adults when hiking. Oregon also supports several packs of gray wolves.

Wild Kiger mustangs, descendants of horses that the Spanish conquistadors brought to the Americas centuries ago, live on Steens Mountain and are identified by their hooked ears, thin dorsal stripes, two-toned manes, and faint zebra stripes on their legs. Narrow trunks and short backs are other distinguishing physical characteristics.

Black bears (Ursus americanus) proliferate in mountain and coastal forests of Oregon. Adults average 200 to 500 pounds and have dark coats. Black bears shy away from people except when provoked by the scent of food, when cornered or surprised, or when humans intrude into territory near their cubs. Female bears tend to have a very strong maternal instinct that may construe any alien presence as an attack on their young. Authorities counsel hikers to act aggressively and defend themselves with whatever means possible if a bear is in attack mode or shows signs that it considers a hiker prey. Jump up and down, shout, and wave your arms. It may help to raise your jacket or pack to make yourself appear larger, but resist the urge to run. Bears can run much faster than humans, and their retractable claws enable black bears to scramble up trees. Furthermore, bears tend to give chase when they see something running.

If you see a bear at a distance, try to stay downwind of it and back away slowly. Bears have a strong sense of smell, and some studies suggest that our body scent is abhorrent to them. Our food, however, can be quite appealing. Campers should place all food in a sack tied to a rope and suspend it 20 feet or more from the ground and away from your tent.

Sportspeople and wildlife enthusiasts alike appreciate Oregon’s big-game herds. Big-game habitats differ dramatically from one side of the Cascades to the other, with Roosevelt elk and black-tailed deer in the west, and Rocky Mountain elk and mule deer east of the Cascades. The Columbian white-tailed deer is a seldom-seen endangered species found in western Oregon. Pronghorn reside in the high desert country of southeastern Oregon. The continent’s fastest mammal, it is able to sprint at over 60 mph in short bursts. The low brush of the open country east of the Cascades suits their excellent vision, which enables them to spot predators.

Many of the most frequently sighted animals in Oregon are small scavengers. Even in the most urban parts of the state, it’s possible to see raccoons, skunks, chipmunks, squirrels, and opossums. West of the Cascades, the dark-colored Townsend’s chipmunks are among the most commonly encountered mammals; east of the Cascades, lighter-colored pine chipmunks and golden-mantled ground squirrels proliferate in drier interior forests. The latter two look almost alike, but the stripes on the side of the chipmunk’s head distinguish them. Expect to see the dark-brown cinnamon-bellied Douglas squirrel on both sides of the Cascades.

Beavers (Castor canadensis), North America’s largest rodents, are widespread throughout the Beaver State, though they’re most commonly sighted in second-growth forests near marshes after sunset. Fall is a good time to spot beavers as they gather food for winter. The beaver has long been Oregon’s mascot, and for good reason: It was the beaver that drew brigades of fur trappers and spurred the initial exploration and settlement of the state. The beaver also merits a special mention for being important to Oregon’s forest ecosystem. Contrary to popular belief, the abilities of Mother Nature’s carpenter extend far beyond the mere destruction of trees to dam a waterway. In fact, the activities associated with lodge construction actually serve to maintain the food chain and the health of the forest by slowing waters to create a habitat for a variety of freshwater and woodland creatures.

You won’t go far in the Oregon coast woodlands or underbrush before you encounter the state’s best-known invertebrates—and lots of them. There are few places on earth where these snails-out-of-shells grow as large (3-10 inches long) or as numerous. The reason is western Oregon’s climate: moister than mist but drier than drizzle. This balance, combined with calcium-poor soil, enables the native banana slug and the more common European black slug (the bane of Oregon gardeners) to thrive.

Because most desert animals are nocturnal, it’s difficult to see many of them. Nonetheless, their variety and exotic presences should be noted. Horned lizards, kangaroo rats, red-and-black ground snakes, kit foxes, and four-inch-long greenish-yellow hairy scorpions are some of the more interesting denizens of the desert east of the Cascade Mountains.

The Pacific Flyway is an important migratory route that passes through Oregon, and the state’s varied ecosystems provide habitats for a variety of species, ranging from shorebirds to raptors to songbirds. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has established viewpoints for wildlife- and bird-watching at 12 Oregon national wildlife refuges.

osprey

In the winter, the outskirts of Klamath Falls become inundated with bald eagles. Along the lower Columbia east of Astoria and on Sauvie Island, just outside Portland, are other bald eagle wintering spots. Visitors to Sauvie Island will be treated to an amazing variety of birds. More than 200 bird species come through here on the Pacific Flyway, feeding in grassy clearings. Look for eagles on the island’s northwest side. Herons, ducks of all sorts, and geese also live on the island.

Other birds of prey, or raptors, abound all over the state. Northeast of Enterprise, near Zumwalt, is one of the best places to see hawks. Species commonly sighted include the ferruginous, red-tailed, and Swainson’s hawks. Rafters in Hells Canyon might see golden eagles’ and peregrine falcons’ nests. Portlanders driving the Fremont Bridge over the Willamette River also might get to see peregrine falcons. Along I-5 in the Willamette Valley, look for red-tailed hawks on fence posts, and American kestrels, North America’s smallest falcons, sitting on overhead wires.

Turkey vultures circle the dry areas during the warmer months. Vultures are commonly sighted above the Rogue River. In central Oregon, ospreys are frequently spotted off the Cascades Lakes Highway south of Bend, nesting atop hollowed-out snags near water (especially Crane Prairie Reservoir).

In terms of sheer numbers and variety, the coast’s mudflats at low tide and the tidal estuaries are among the best birding environments. Numerous locations along the coast—including Bandon Marsh, Three Arch Rocks near Cape Meares, and South Slough Estuarine Research Reserve near Coos Bay—offer outstanding opportunities for spotting such pelagic species as pelicans, cormorants, guillemots, and puffins, as well as waders such as curlews, sandpipers, and plovers, plus various ducks and geese. Rare species such as tufted puffins and the snowy plover enjoy special protection here, along with marbled murrelets, which feed from the ocean but nest in mature forests up to 30 miles inland. The Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge, which comprises all the 1,400-plus offshore islands, reefs, and rocks from Tillamook Head to the California border, is a haven for the largest concentration of nesting seabirds along the West Coast, thanks to the abundance of protected nesting habitat.

Malheur Wildlife Refuge, in the southeast portion of the state, is Oregon’s premier bird and birder retreat and stopover point for large groups of sandhill cranes, Canada and snow geese, whistling swans, and pintail ducks.

In the mountains, look for Clark’s nutcracker or the large Steller’s jay, whose grating voice and dazzling blue plumage often commands the most attention. Mountain hikers are bound to share part of their picnic lunch with these birds. At high elevations, the quieter Clark’s nutcracker will more likely be your guest.

Unfortunately, the western meadowlark, the state bird, has nearly vanished from western Oregon due to loss of habitat, but thanks to natural pasture east of the Cascades, you can still hear its distinctive song. The meadowlark is distinguished by a yellow underside with a black crescent pattern across the breast and white outer tail feathers.

Long before Europeans came to this hemisphere, indigenous people thrived for thousands of years in the region of present-day Oregon. The leading theory concerning their origins maintains that their ancestors came over from Asia on a land or ice bridge spanning what is now the Bering Strait.

Despite common ancestry, the people on the rain-soaked coast and in the Willamette Valley lived quite differently from those on the drier eastern flank of the Cascade Mountains. Those west of the Cascades enjoyed abundant salmon, shellfish, berries, and game. Broad rivers facilitated travel, and thick stands of the finest softwood timber in the world ensured that there was never a dearth of building materials. A mild climate with plentiful food and resources allowed the wet-siders the leisure time to evolve a complex culture rich with artistic endeavors, theatrical pursuits, and such ceremonial gatherings as the traditional potlatch, where the divesting of one’s material wealth was seen as a status symbol.

After contact with traders, Chinook, an amalgam of Native American tongues with some French and English thrown in, was the common argot among the diverse nations that gathered in the Columbia Gorge each year. It was at these gatherings that the coast and valley dwellers would come into contact with Native Americans from east of the Cascades. These dry-siders led a seminomadic existence, following game and avoiding the climatic extremes of winter and summer in their region. In the southeast desert of the Great Basin, seeds and roots added protein to their diet.

The introduction of horses in the mid-1700s made hunting much easier. In contrast to their counterparts west of the Cascades, who lived in 100-by-40-foot longhouses, extended families in the eastern groups inhabited pit houses when not hunting. The demands of chasing migratory game necessitated caves or simple rock shelters.

Twelve separate nations populated what is now Oregon. Although these were further divided into 80 tribes, the primary allegiance was to the village, and “nation” referred to language groupings such as Salish and Athabascan.

The coming of European settlers meant the usurpation of Native American homelands, exposure to European diseases such as smallpox and diphtheria, and the passing of ancient ways of life. Violent conflicts ensued on a large scale with the influx of settlers doing missionary work and seeking government land giveaways in the 1830s and 1840s. In the 1850s, mining activity in southern Oregon and on the coast incited the Rogue River Wars, adding to the strife brought on by annexation to the United States.

These events compelled the U.S. federal government to send in troops and eventually to set up treaties with Oregon’s first inhabitants. The attempts at arbitration in the 1850s added insult to injury. Tribes of different—indeed, often incompatible—backgrounds were rounded up and grouped together haphazardly on reservations, often far from their homelands. In the century that followed, modern civilization destroyed much of the ecosystem on which these cultures were based. An especially regrettable result of colonization was the decline of the Columbia River salmon runs due to overfishing, loss of habitat, and pollution. This not only weakened the food chain but treated this spiritual totem of the many Native American groups along the Columbia as an expendable resource.

For a while, there was an attempt to restore the balance. In 1924 the federal government accorded citizenship to Native Americans. Ten years later, the Indian Reorganization Act provided self-management of reservation lands. Another decade later, a court of treaty claims was established. In the 1960s, however, the government, acting on the premise that Native Americans needed to assimilate into mainstream society, terminated several reservations.

Recent government reparations have accorded many indigenous peoples preferential hunting and fishing rights, monetary and land grants, and the restoration of status to certain disenfranchised bands. In Oregon, there are now nine federally recognized tribes and six reservations: Warm Springs, Umatilla, Burns Paiute, Siletz, Grand Ronde, and Coquille. Against all odds, their culture is still a vital part of Oregon; the 2010 census estimated that over 53,000 Oregonians are Native American. Native American gaming came to Oregon in the mid-1990s, and Native Oregonians now operate a number of lucrative casinos in the state; the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, owners of the phenomenally popular Spirit Mountain Casino, are among the state’s biggest philanthropists.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Spanish, British, and Russian vessels came to offshore waters here in search of a sea route connecting the Atlantic with the Pacific. Accounts differ, but the first sightings of the Oregon coast have been credited to either Spanish explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (in 1543) or English explorer Francis Drake (in 1579). Other voyagers of note included Spain’s Vizcaíno and De Aguilar (in 1603) and Bruno de Heceta (in 1775), and Britain’s James Cook and John Meares during the late 1770s, as well as George Vancouver (in 1792).

Sea otter and beaver pelts added impetus to the search for a trade route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. While the Northwest Passage turned out to be a myth, the fur trade became a basis of commerce and contention between European, Asian, and eventually American governments.

The United States took interest in the area when Robert Gray sailed up the Columbia River in 1792. The first U.S. overland excursion into Oregon was made by the Corps of Discovery in 1804-1806. Dispatched by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the lands of the Louisiana Purchase and beyond, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their party of 30 men—and one woman, Sacajawea—trekked across the continent to the mouth of the Columbia, camped south of present-day Astoria during the winter of 1805-1806, and then returned to St. Louis. Lewis and Clark’s exploration and mapping of Oregon threw down the gauntlet for future settlement and eventual annexation of the Oregon Territory by the United States. The expedition also initially secured good relations with the Native Americans in the West, thus establishing the preconditions to trade and the missionary influx.

Following Lewis and Clark’s journey, there were years of wrangling over the right of the United States to settle in the new territory (when Lewis and Clark made their journey, Oregon and Washington were British territory). Nonetheless, American John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company established a trading fort at Astoria in 1811, though British war ships soon dispersed the settlement. It wasn’t until 1818, as part of the settlement of the War of 1812, that the country west of the Rockies, south of Russian America, and north of Spanish America was open for use by U.S. citizens as well as British subjects.

During the 1820s, the British Hudson’s Bay Company continued to hold sway over Oregon country by means of Fort Vancouver on the north shore of the Columbia. More than 500 people settled here under the charismatic leadership of John McLoughlin, who oversaw the planting of crops and the raising of livestock. Despite a growing number of farms and settlements along the Willamette River, as the trappers began to put down roots, several factors presaged the demise of British influence in Oregon. Most obvious was the decline of the fur trade as well as Britain’s difficulty in maintaining its far-flung empire. Less apparent but equally influential was the lack of European women in a land populated predominantly by male European trappers and explorers. If the Americans could attract settlers of both genders, they’d be in a position to create an expanding population base that could dominate the region.

The first step in this process was the arrival of missionaries. In 1834, Methodist soul-seekers led by Jason Lee settled near Salem. Four years later, another mission was started in the eastern Columbia River Gorge. In 1843, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman’s missions started up on the upper Columbia in present-day Walla Walla, Washington. The missionaries brought alien ways and diseases for which the Native Americans had no immunity. As if this weren’t enough to provoke a violent reaction, the Native Americans would soon have their homelands inundated by thousands of settlers lured by government land giveaways.

Despite Easterners’ ignorance of western geography and the hardships it held, more than 53,000 people traversed the 2,000-mile Oregon Trail between 1840 and 1850 en route to the Eden of western Oregon. Though many of these settlers were driven by somewhat utopian ideals, there was also the attraction of free land: This march across the frontier was fueled by the offer of 640 free acres that each white adult male could claim in the mid-1840s.

In 1850, the Donation Land Act cut in half the allotted free acreage, reflecting the diminishing availability of real estate. But although a single pioneer man was now entitled to only 320 acres, and single women were excluded from land ownership, as part of a couple they could claim an additional 320 free acres. This promoted marriage and, in turn, families on the western frontier and helped to fulfill Secretary of State John C. Calhoun’s prediction that American families could outbreed the Hudson’s Bay Company’s bachelor trappers, thus winning the battle of the West.

Another route west was the Applegate Trail, pioneered by brothers Lindsay and Jesse Applegate in the mid-1840s. Each had lost sons several years before to drowning on the Columbia River. The treacherous rapids here had initially been the last leg of a journey to the Willamette Valley.

On their return journey to the region, the brothers departed from the established trail when they reached Fort Hall, Idaho. Veering south from the Oregon Trail across northern Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, they traversed the northeast corner of California to enter Oregon near present-day Klamath Falls. A southern Oregon gold rush in the 1850s drew thousands along this route.

There was enough unity among American settlers to organize a provisional government in 1843. Then, in 1848, the federal government decided to accord Oregon territorial status. The new Oregon Territory got off to a rousing start thanks to the California gold rush of 1849. The rush occasioned a housing boom in San Francisco and a need for lumber, and the dramatic population influx created instant markets for the agriculture of the Willamette Valley. The young city of Portland was in a perfect position to channel goods from the interior to coastal ports and prosper economically.

However, strategic importance and population growth alone do not explain Oregon becoming the 33rd state in the Union. In 1857, the Dred Scott decision had become law. This had the effect of opening Oregon to slavery, as a territory didn’t have the legal status to forbid the institution as a state had. While slavery didn’t lack adherents in Oregon, the prevailing sentiment was that it was neither necessary nor desirable. If Oregon were a state instead of a territory, however, it could determine its own policy regarding slavery. A constitution (forbidding free black residents as well as slavery) was drawn up and ratified in 1857, and sent to Washington DC for approval. However, the capital was engulfed in turmoil about the status of slavery in new American states, and only after a year and a half of petitioning did Oregon finally enter the Union, on Valentine’s Day 1859.

During the years of the Civil War and its aftermath, internal conflicts were the order of the day within the state. By 1861, good Willamette Valley land was becoming scarce, so many farmers moved east of the Cascades to farm wheat. They ran into violent confrontations with Native Americans over land. Miners encroaching on Native American territory around the southern coast eventually flared into the bloody Rogue River Wars, which would lead to the destruction of most of the indigenous peoples of the coast.

In the 1870s, cattle ranchers came to eastern Oregon, followed by sheep ranchers, and the two groups fought for dominance of the range. However, overproduction of wheat, uncertain markets, and two severe winters spelled the end to the eastern Oregon boom. Many eastern Oregon towns grew up and flourished for a decade, only to fall back into desert, leaving no trace of their existence.

In the 1860s and 1870s, Jacksonville in the south became the commercial counterpart to Portland, owing to its proximity to the Rogue Valley and south coast goldfields as well as the California border. The first stagecoach, steamship, and rail lines moved south from the Columbia River into the Willamette Valley; by the 1880s, Portland was joined to San Francisco and the east by railroad and became the leading city of the Pacific Northwest.

In the modern era, Oregon blazed trails in the thicket of governmental legislation and reform. The so-called Oregon system of initiative, referendum, and recall was first conceived in the 1890s, coming to fruition in the first decade of the 1900s. The system has since become an integral part of the state’s democratic process. In like measure, Oregon’s extension of suffrage to women in 1912, a 1921 compulsory education law, and the first large-scale union activity in the country during the 1920s were red-letter events in U.S. history. However, blacks were still excluded from residency in the state.

The 1930s were exciting years in the Pacific Northwest. Despite widespread poverty, the foundations of future prosperity were laid during this decade. New Deal programs such as the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps undertook many projects around the state. Building roads and hydroelectric dams created jobs and improved the quality of life in Oregon, in addition to bolstering the country’s defenses during wartime. Hydroelectric power from the Bonneville Dam, completed in 1938, enabled Portland’s shipyards and aluminum plants to thrive. Low utility rates encouraged more employment and settlement, while the Columbia’s irrigation water enhanced agriculture.

Thanks to mass-production techniques, 10,000 workers were employed in the Portland shipyards. But in addition to laying the foundations for future growth, the war years in Oregon and their immediate aftermath were full of trials for state residents. Vanport—at one time a city of 45,000—grew up in the shadow of Kaiser aluminum plants and the shipyards north of Portland, but it was washed off the map in 1948 by a Columbia River flood. Tillamook County forests, which supplied Sitka spruce for airplanes, endured several massive fires that destroyed 500 square miles of trees.

With the perfection of the chainsaw in the 1940s, the timber industry could take advantage of the postwar housing boom. During that decade, the state’s population increased by nearly 50 percent, growing to over 1.5 million. During the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers carried out a massive program of new dam projects, resulting in construction of The Dalles, John Day, and McNary Dams on the main stem of the Columbia River as well as the Oxbow and Brownlee Dams on the Snake River. In addition, flooding on the Willamette River was tamed through a series of dams on its major tributary watersheds, the Santiam, the Middle Fork of the Willamette, and the McKenzie.

Politically, the late 1960s and 1970s brought environmentally groundbreaking measures spearheaded by Governor Tom McCall. The bottle bill, land use statutes, and the cleanup of the Willamette River were part of this legacy. The 1990s saw the Oregon economy flourishing, fueled by the growth of computer hardware and software industries here as well as a real estate market favorable to an Oregon Trail-like stream of new settlers. The demographics of Oregon’s new arrivals as well as its changing economic climate helped to sustain the state’s image as a politically maverick state, with Oregon leading the way in physician-assisted suicide, extensive vote-by-mail procedures, legalized marijuana, and the Oregon Health Plan, a low-cost health insurance program for low-income residents.

Oregon’s economy has traditionally followed a boom-bust cycle. Even though it has in recent decades diversified away from its earlier dependence on resource-based industries, the economic bust of 2008 left over 10 percent of Oregonians unemployed, second only to Michigan in unemployment.

The state’s major industries today include a booming high-tech sector (Intel is the state’s largest employer), primary and fabricated metals production, transportation equipment fabrication, and food processing. Important nonmanufacturing sectors include wholesale and retail trade, education, health care, and tourism. Portland is home to a number of sports and recreational gear companies, including Nike, Adidas America, Columbia, and other sportswear companies with headquarters in the Rose City area.

In agriculture, organic produce, often sold in farmers markets, and other specialty products have helped many small farmers to survive. Other agricultural products include nursery crops (Monrovia is the nation’s largest Christmas tree nursery, and Oregon is the number one Christmas tree state); wine grapes; berries, cherries, apples, and pears; and gourmet mushrooms, herbs, and cheese. Wheat, cattle, potatoes, and onions are the stalwarts of the eastern Oregon economy. Oregon wineries, most of them small operations, turn out increasingly excellent wine to meet the demands of a thirsty global market. With the legalization of marijuana in late 2015, the enormous black market in pot production has edged into the mainstream economy, with over $60 million in tax revenues generated in 2016.