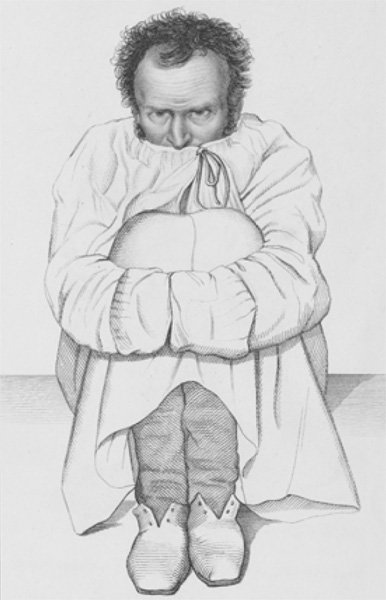

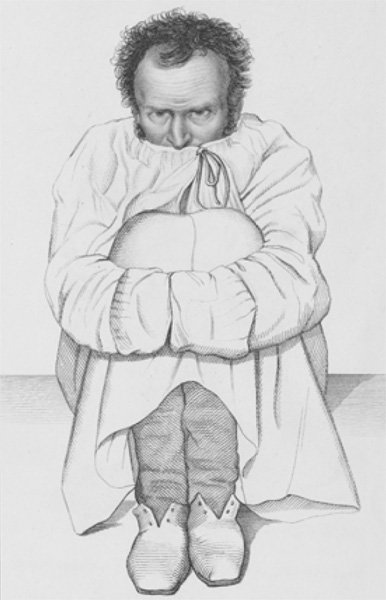

Man in a strait-jacket. French asylum, 1838. Wellcome Collection

Henri Laborit broke the surface and gasped for air. He had nearly been taken down, the Sirocco pulling him under until he fought free and kicked up through the dark. He was one of the lucky few with a life jacket. The sea was being churned by panicked men. Oil fires lit the surface. He had to fight off three soldiers, “unfortunate idiots,” he called them, who, it appeared, did not know how to swim. They were panicking, arms windmilling, clutching at anything that floated, trying to use Laborit as a life raft. “I had to get rid of them,” he wrote later, although he never wrote how he did it. Laborit kept his distance from the dying men, fires, and bobbing bodies, turned on his back—a swimmer’s trick—and looked at the stars.

It was just after one in the morning the night of May 30, 1940. Henri Laborit was a junior medical officer on the small French destroyer Sirocco. They had been helping with the great evacuation of troops at Dunkirk, after the Nazi Blitzkrieg had smashed three Allied armies and trapped the survivors in a little pocket around the port, their backs to the English Channel. Every Allied ship within a day’s steaming had raced to the area to pull men out of France. Laborit’s destroyer arrived at the height of the action, zigzagging toward shore through clouds of black smoke and the remains of half-sunken ships. Soldiers lined the seawalls and beaches; some stood hip-deep in the water, rifles raised above their heads. The Germans were trying to kill everything that moved. “There were no doubts in the minds of the crew that their days were numbered,” Laborit remembered. But the Sirocco managed to pick up eight hundred French riflemen, packed them shoulder to shoulder on deck, and, as dusk fell, pulled away. All they had to do now was make it to England.

Dover was less than fifty miles away, but the waters off Dunkirk were shallow and treacherous, and German planes were everywhere, so they moved slowly along the coast for miles, waiting for dusk and the chance to make a break for it. Everyone was on high alert. Around midnight, just as they were ready to dash for England, someone spotted a German torpedo boat emerging from behind a buoy. Laborit watched as two torpedoes sped toward them and barely missed, just off the bow, wakes shining in the dark. Then a second round of torpedoes hit them dead-on. The Sirocco shuddered; Laborit felt the stern lift. German dive-bombers zeroed in on the flames, and a second tremendous explosion ripped the Sirocco open. Laborit thought the ship’s ammunition magazine had been hit. He saw riflemen’s bodies flying through the air. Then he was in the water.

The ship sank quickly, the bombers flew off to find other prey, and Laborit floated on his back. As the hours went by, he saw men around him slowly losing their strength. He was very cold; his mind began to wander. He had been trained as a physician just before the war and knew what was happening. The freezing sea was sucking the heat out of his body, and hypothermia was setting in. If it went on much longer, he would die. How long? His fingers and feet were already starting to go numb, legs getting sluggish. Lower the body’s temperature enough and you went into a sort of shock reaction, blood pressure plummeting, breathing growing shallow, the body going white and still. Would it take an hour? Several?

Laborit saw it happening around him. Ninety percent of the riflemen they picked up at Dunkirk would die that night. So would half of the Sirocco’s crew.

He forced himself to keep moving. He noticed that he was still wearing his helmet, a stupid thing to do, and fumbled with the strap until he got it off. He watched it slowly fill with seawater. There must be a hole in it, he thought. He stared at the helmet until it sank. His mind was slowing down.

Somehow he made it until dawn, when he saw a few dim lights and heard some distant calls. A small British warship was looking for survivors. He could see men, using the last of their strength, thrashing desperately around it, clamoring to get aboard. Sailors on deck were throwing lines, and the swimmers were clawing at one another to get to them. It was a madhouse. The Sirocco’s survivors were so weak that some could not make the climb—they would get partway up, lose their grip, and fall back on top of the others. Men were drowning. Laborit forced himself to hold off, waiting for the chaos to settle. Then, with an enormous effort, he swam alongside, grabbed a slippery rope, and began hauling himself up. He made the rail, was pulled over, and immediately passed out. He came to in a tub of warm water with someone slapping his face, saying, “C’mon, Doc, put some effort into it!”

Laborit, suffering from exhaustion and exposure, was taken to a French military hospital where, as he recovered, he fell into an odd, floaty sort of depression. Today we would call it post-traumatic stress. All Laborit knew was that he felt off-balance, as if the solid ground beneath him had turned to quicksand. “I found myself distraught by the idea of having to continue to live,” he remembered. He was twenty-six years old.

But here, too, he fought his way back. There was some public attention to distract him. He was one of the heroes of the Sirocco, as the press called them. He was awarded a medal. He found comfort in working at medical duties. He developed a dark sense of humor. But still everything felt a little distant, as if he were watching life through a window.

When the French military felt he had recovered enough, his commanders decided that he would benefit from a change of scene and sent him to a naval base in Dakar, the capital of Senegal in North Africa. Here, in the sun and sand, he practiced general medicine for a few hours in the mornings and spent the rest of the day painting, writing, and riding horses. He had a slight build but was good-looking, almost movie star handsome with his thick, dark hair; he was also smart, ambitious, and accustomed to money—his father was a physician, his mother came from an aristocratic family—and a little snobby. He hated being exiled with his wife and small children in the sweltering “backwater” of Africa and desperately wanted to get back to France. To take his mind off his boredom, he decided to specialize in surgery. He found mentors among the doctors of Dakar and essentially trained himself in the arts of cutting and sewing, using cadavers from the local morgue. He had skillful hands. But he had little patience.

Once he started operating on living patients, despite his skill and best efforts, things often went wrong. Regularly, seemingly for no reason, in the middle of an operation a wounded soldier’s blood pressure would nose-dive, his breath would grow shallow, and his heart would start racing. It was a bad sign. Often the patient died on the table, not from the operation itself, but from a condition called “surgical shock.” No one knew what caused it, and at the time there was little that could be done to counter it. No one knew why some patients went into shock while others did not. Nothing seemed to alter the odds.

Laborit decided to find some answers. As he moved from post to post through the rest of the war, he sought out whatever medical literature he could find on the subject of surgical shock. And he began to put together a picture. Shock, most experts thought, was a response to injury (including the injury of being laid out on a table and cut open by a surgeon). Researchers were just learning that wounded animals react to injury by releasing a flood of chemicals into their blood, molecules like adrenaline that trigger a flight-fight-or-freeze response. Adrenaline increases heart rate, speeds up metabolism, and alters blood flow. Laborit came to believe that the keys to surgical shock would be found in the chemicals the body released into the blood when it was injured.

That was one approach, but not the only one. Some researchers thought shock was more mental than physical. After all, a shock response could be triggered by fear as well as injury. Threaten someone with a knife—convince them you’re going to hurt them—and their heart speeds up, their breath grows ragged, they sweat. Mental stress by itself, in other words, can cause a shock response. Laborit had seen that with his own patients, who, in the hours before an operation, sometimes got so tense, so anxious about the coming pain, that they started exhibiting signs of shock well before scalpel touched skin. Maybe surgical shock was simply an extension of this—a natural reaction that went too far, that somehow spiraled out of control.

Laborit brought the two ideas together. His thinking went like this: The patient’s anxiety and fear of pain before an operation triggered the release of chemicals in the blood. Then the physical shock of the operation ramped it up a notch. The mental stress and physical reactions were tied.

So perhaps the answer was to short-circuit the process by easing the fear before the operation. Ease the fear, lower the anxiety, and you might be able to block or slow the blood chemicals from triggering fatal shock.

But what were these chemicals? Very little was known about molecules like adrenaline because they were released in very small amounts, were quickly diluted to almost undetectable levels in the blood, and then disappeared entirely within minutes. More was being learned about adrenaline all the time, but it wasn’t the only such molecule—there were others yet to be identified. Laborit read everything he could on the subject, thereby becoming one of those rare surgeons who deeply understood biochemistry and pharmacology, and began to play with ideas about moderating stress chemicals in the body.

His patients became his test subjects. When the war ended, Laborit was still in North Africa. But now his ennui was lifted because he was engaged in his research, testing ways to try to calm his patients and put them at ease before their operations. He would mix various drugs into chemical cocktails designed to lower anxiety. It was hard to find the right mix of ingredients. Physicians in the past had tried a lot of things to keep patients quiet, from shots of whiskey to sleeping pills, morphine to knockout drops (see this page). But all of these, in Laborit’s view, were imperfect. All of them had side effects, some of which could be dangerous. They weakened patients as well as relaxed them. They put patients to sleep. Laborit wanted his patients strong and tranquil, unworried before their operations, but not unconscious until they were actually on the table. The Greeks had a word for what he wanted: ataraxia, the mental state of a person who was free from stress and anxiety but at the same time strong and virtuous. He wanted to create ataraxia with drugs. So he kept searching and testing.

To this he added another idea, perhaps spurred by his time in the water after the Sirocco sank. He decided to try cooling his patients down. If he could slow their metabolisms, he thought, he might be able to help relax the shock reaction. He pioneered a procedure he called “artificial hibernation,” using ice to cool his patients along with the drugs.

This approach, a historian later wrote, was frankly revolutionary. Other researchers were going the opposite way, trying to counter shock once it started by giving shots of adrenaline—exactly the wrong thing, Laborit thought. He was convinced that his artificial hibernation, coupled with the right drugs, would do the job.

By 1950, Laborit was reporting a string of positive results in medical journals. His work gained him so much attention that his bosses decided to rescue him from the hinterlands, bringing him to the center of all things French, Paris.

Ah, Paris! Paris was the world to any ambitious Frenchman (or -woman). It was home of the nation’s political leaders and business headquarters; its religious elite and military top brass; its best writers, composers, and artists; the nation’s top university (the Sorbonne) and leading intellectuals (the French Academy); its finest houses and most beautiful music, fashion, and food; the best libraries and research centers, museums, and training centers. If you were French and you were a leader in your field, your heart yearned for a post in Paris.

And now Laborit had arrived. He was transferred to the nation’s most prestigious military hospital, the Val-de-Grâce, just a few blocks from the Sorbonne. There, with access to a wide range of experts and far greater resources, he widened his research.

He needed a drug expert, and he found one in the form of an enthusiastic researcher named Pierre Huguenard. Laborit and Huguenard went to work perfecting his artificial hibernation technique, accompanied by cocktails shaken up from atropine, procaine, curare, different opioids, and sleeping drugs.

Another of the chemicals the body released in response to injury, histamine, caught their interest. Histamines were involved in all sorts of things in the body, not only released in response to injury but also involved in allergic reactions, motion sickness, and stress. Perhaps histamine played a role in the shock reaction. So Laborit threw another ingredient into his cocktail: an antihistamine, a new kind of drug then being intensively developed for the treatment of allergies. And that’s when things began to get interesting.

Antihistamines looked like the next great family of miracle drugs. They had effects on everything from hay fever to seasickness, the common cold to Parkinson’s disease. Drug companies were working feverishly trying to sort it all out and make versions that could be patented.

But, like all drugs, they also had side effects. One was particularly troubling when it came to marketing: Antihistamines often caused what one observer called “a disturbing drowsiness” (today’s nondrowsy antihistamines were still decades away). This was not like the sleepiness caused by sedatives and sleeping pills. Antihistamines didn’t slow down everything in the body. Instead, they seemed to be aimed toward a specific part of the nervous system: what doctors in the 1940s referred to as the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves (today it’s the autonomic nervous system). These make up the body’s background nervous system, the signals and responses that operate below the level of our conscious minds; they are the nerves that help regulate breathing, digestion, and heartbeat, for example. And it would be among these nerves, Laborit thought, that the secrets of the shock reaction would be found. He wanted a drug that acted on these nerves specifically, without greatly affecting the conscious mind. Antihistamines looked like they might be just the thing.

So he and Huguenard began testing. They found that adding the right dose of the right antihistamine in the hours before surgery yielded patients who, although still conscious, Laborit wrote, “felt no pain, no anxiety, and often did not remember the operation.” As an added benefit, Laborit found that his patients needed less morphine for pain. His antihistamine-enriched cocktails, along with artificial hibernation, were resulting in less surgical shock and fewer deaths.

But there was much more to do. He didn’t really want an antihistamine in his cocktail—he wasn’t treating allergies or motion sickness, after all—as much as he wanted one of the side effects of an antihistamine. He was looking only for the reduced anxiety, the euphoric quietude he had seen in some patients. He wanted an antihistamine that was all that side effect. So he wrote to France’s biggest drug company, Rhône-Poulenc (RP), and asked the researchers there to find one.

Luckily, he reached the right people at the right time. RP was very actively looking for newer, better antihistamines and, like all drug companies, had plenty of failures sitting on the shelf—drugs that had been too toxic, or had too many side effects. They began retesting their failures.

A few months later, in the spring of 1951, the firm delivered to Laborit an experimental drug called RP-4560. They had stopped working with it because it had virtually no use as an antihistamine. But it had a strong effect on the nervous system. Animal tests had shown it was relatively safe. It might be just what Laborit was looking for.

It turned out to be the best thing he’d ever thrown into a cocktail. It was very powerful; a small amount was all that was needed. And it did the job: RP-4560 given before a variety of different kinds of surgery, from wound treatment to minor operations, lowered patients’ anxiety, improved mood, and lessened the need for other drugs. The patients who took it were awake and aware but seemed to tolerate their pain better and required less anesthesia in order to lose consciousness. It was strange, really. It wasn’t that the pain was gone. They realized that they were in pain, but seemed not to worry about it. They knew they were going in for an operation, but seemed not to care. They were disinterested, Laborit found—“detached” from their stress.

His findings became the talk of Val-de-Grâce. And Laborit, now enthusiastic, became a promoter. One day over lunch in the staff canteen, he listened as a friend—the head of the hospital’s psychiatric department—bemoaned the need to put his severely ill mental patients in straitjackets, an old lament raised by generations of caregivers for the insane. How sad it was that in many cases the mad were too agitated, too manic, too dangerous to be cared for without restraints. They would scream and thrash, sometimes attacking others or hurting themselves. So they had to be knocked out with drugs, or strapped into beds, or straitjacketed. What a pity.

It gave Laborit an idea. He told his luncheon companions that instead of restraints, they might want to try giving these manic patients a dose of RP-4560 and cooling them down with ice.

Every morning, the mad could be found in the waiting room at Sainte-Anne, where the dregs of the night before had been hauled in by police or family members, “brains boiling with fury, overwhelmed with anguish, or dead-beat,” one physician recalled. They were the maniacs, the ravers, the ones who saw hallucinations and heard voices, the despondent, the lost.

When it became too much, they ended up at Sainte-Anne, the only psychiatric hospital within the boundaries of Paris. Every big city had its own version of Sainte-Anne, a government-sponsored mental hospital, an asylum designed to remove the mad from society, to help them and keep them safe—and out of sight.

They were called mental “asylums” for good reason: The mentally ill needed a refuge. For most of history, the mad had been left to the mercy of their families, who with rare exceptions hid the worst afflicted in back bedrooms and locked them into basements. Some were treated kindly, and others were chained, beaten, and starved.

That changed with the Industrial Revolution and the growth of cities. With increasing stress and the dispersion of families, the mad increasingly ended up on the streets. They became the responsibility of others—or of no one.

Charitable organizations were formed, and social movements mounted to care for them humanely. Beds, food, and medical care had to be found. In America, the answer in the nineteenth century was to build large asylums, designed to be models of advanced care, with park-like grounds, airy workshops, and professional therapy overseen by physicians trained specifically in the treatment of mental disorders. The asylum’s design would allow separation of men from women, the violent from the nonviolent, the curable (who were often housed in the front, most visible rooms) from the incurable (often locked in the back, where the cries and smells would be less troubling to visitors). Diets would be healthful and simple, punishment would be rare, and here, as one writer put it, “they would gradually come to their senses thanks to the salutary effects of the asylum environment.”

There would be benefits for medical science, too. With all sorts of madness gathered in one place, physicians of the mind would be better able to study a range of conditions under somewhat controlled circumstances, allowing a deeper understanding of mental disease, and increasing the chance of finding cures.

Man in a strait-jacket. French asylum, 1838. Wellcome Collection

That was the ideal, in any case. And in many ways, it was successful.

In Britain, for example, no more than a few thousand patients were kept—imprisoned, often—in a handful of mental asylums like the infamous Bethlem Royal Hospital, outside of London, better known as Bedlam. In the eighteenth century, Bedlam became infamous for allowing bored visitors to pay a little money and walk through to goggle at the inmates, turning madness into an evening’s entertainment. A century later there were sixteen large asylums in the London area alone. The average number of patients per asylum rose from less than sixty in 1820 to ten times that number within a few decades. In America, numbers of patients rose just as fast. By 1900 American asylums were buckling under the strain of 150,000 mental patients.

Most of these were supported by the public, through state and county budgets, or by charitable organizations. The result was that the price of care in these public asylums was low for families. The numbers kept going up as more and more families dropped off their senile grandparents, alcoholic uncles, and mentally disabled children at bargain prices. Police did the same with drug addicts, corner ravers, and disturbers of the peace. Workhouses, poorhouses, hospitals, and jails added their own overflow. The huge asylums filled to bursting.

The Hospital of Bethlem [Bedlam] at Moorfields, London: seen from the north, with people walking in the foreground. Engraving. Wellcome Collection

Many of these inmates were curable. Asylums worked best for cases in which the patient had suffered a temporary mental breakdown or was working through a trauma and who, after a few weeks of rest and peace, could be released.

But many were deemed incurable cases. These included the “senile” elderly (today we would say they have some form of dementia, like Alzheimer’s disease), the developmentally disabled, and those who had lost touch with reality entirely and could not find their way back. This latter group—the ones who curled into a corner and didn’t move for months on end, or talked nonsense endlessly, saw things that weren’t there, or heard voices telling them what to do—are now generally termed schizophrenic. Again, because no one was sure what caused any of these diseases, no one could fix them. As one expert put it, “In 1952, the six inches between one’s ears were the least explored territory on the planet.” What was known was this: Once these “incurables” entered an asylum, chances were they’d never leave. They were in the back rooms for life, joined by more every year. The overall numbers just kept going up, and the proportion of worst-case patients who could not be treated—only cared for—got bigger every year. By the early twentieth century almost every asylum was overstuffed and understaffed. They had morphed from places of rest and recuperation to loud, crowded holding pens, “loony bins” concerned less with curing than with security and sedation. Asylums became, as one expert said, “dustbins for hopeless cases.”

In addition—and this turned out to be important—they were ever-deepening money-sinks for government budgets. The big asylums were, for the most part, funded with state and county tax monies, and as they grew, every year they took a bigger and bigger bite out of government budgets. Every attempt to cut costs led to less humane care. Reports of patient abuse grew. Taxpayers were getting tired of it.

What about the science? Here, too, nothing good seemed to be happening. The sad fact is that the chances of getting cured in a mental asylum in 1950 were not much better than they had been in 1880. There had been great excitement about the possibilities of better care through lobotomies and electroshock when these methods were first introduced in the early twentieth century, but after the enthusiasm waned, every new advance soon proved marginal. When it came to their toughest cases, especially schizophrenia, asylum doctors were making little headway. Psychiatrists, despite amassing an impressive and ever-growing knowledge base about mental health, were unable for the most part to help their sickest patients.

The morning routine at Sainte-Anne mental hospital in Paris went like this in 1952:

The well-dressed heads of the hospital’s main wards would visit the waiting area and review what the night had washed up at their door. The waiting area was a rich panoply of all that could go wrong with the human mind. Physicians could find examples of every sort of insanity, and noted those who fell into an area of current research interest. The morning review, one Sainte-Anne physician wrote, was like “Going shopping in the mental illness market.”

The most interesting cases were marked down for those researchers who were known to have an interest in them. The less severe cases, those most likely to be helped, were taken to the Free Department for voluntary inpatients (“voluntary” was a misnomer; a few came in on their own, but most were brought by police or committed by family members). The tougher cases ended up in the more restrictive Men’s or Women’s Departments, the wards with locked doors, where they could be carefully monitored and, if necessary, restrained.

Somewhere else in the hospital on those mornings in the early 1950s, striding the halls or marching across the grounds trailed by a retinue of underlings, was the director of Sainte-Anne, Jean Delay. He was a short but commanding figure, a true intellectual in the mid-twentieth-century mold, insightful in many ways, interested in many things, and endlessly skeptical. “The most brilliant, the most secretive, the most discrete, the most sensitive, and the most rigorous of French psychiatrists,” a colleague wrote after his death. Delay was a true “artist of medicine.”

As a young man he had wanted to be a writer, and in addition to his work in mental health he would pen fourteen works of literature, including well-received novels and biographies, an effort that would win him election to that intellectual zenith of literature and thought, the French Academy.

And so Delay, a forceful figure in an elegant dark suit, watched over Sainte-Anne, evaluating the scene as if from a distance, weighing, analyzing, and transforming the hot simmer of patients into columns of cool facts, keeping his feelings to himself, focusing on research that could help, looking for measurable results.

Delay was careful, correct, and precise in everything. Freud and his followers might have made a fad of psychoanalysis and talk therapy, and wealthy neurotics might get some relief from talking about their dreams and sex lives, but Delay knew that this meant nothing in a mental asylum. His patients had deeper problems, likely rooted in physical dysfunctions of their brains. Delay believed that severe mental illness came from biology, not personal experience. He was, for his day, a revolutionary who wanted to free psychiatry from Freud’s woolly thinking and unproven theories and move it toward becoming a real science, rooted in measurement and statistics, able to take its place proudly among the accepted fields of medicine. The keys, he believed, would be found in the tissues and chemicals of the brain.

But his brilliance and beliefs had yielded little in the way of cures. This was a failure rooted in the same problem that faced all psychiatrists: In the end, no one knew what caused madness. Finding cures, therefore, was a near impossibility. Psychiatrists ended up trying almost any therapy in hopes of finding something that worked, but nothing seemed able to alter the trajectory of deep madness. Many asylum doctors and staff members became despondent after years of butting their heads against the wall; depression was common among caregivers, and suicide was not unknown. It came from their inability to help those most in need of help. One of Delay’s top lieutenants felt this way after a decade working at Sainte-Anne: “What I had learned in nearly ten years did not help me at all in treating mental illness. . . . I was a powerless onlooker.”

The raving and thrashing young man had been in and out of Val-de-Grâce twice already, and both times the doctors at Laborit’s Paris military hospital had done all they could for him: sedatives, anesthetic treatments, insulin coma treatments, and twenty-four electroshock sessions. “Jacques Lh,” as he was called in their reports, would begin to respond, get a little calmer, and they would let him out. A few weeks later he would be back, out of control, threatening violence. So this time, in January 1950, they tried something new: Laborit’s experimental drug, RP-4560. No one knew how much to give. For his surgical patients, Laborit had found that 5 to 10 milligrams worked well. So the Val-de-Grâce psychiatrists gave Jacques ten times that much. Within a few hours, the young man was asleep. And when he woke, to the physician’s astonishment, he remained calm for eighteen hours before falling back into his mania. They gave him another dose of Laborit’s drug, and another, as often as they thought necessary, at levels they hoped would work. They tossed in some sedatives and whatever else they thought might help. And something strange happened. Jacques’s calm periods lengthened. By the end of three weeks, his condition had improved so dramatically that he was, as the reports noted, rational enough to play bridge. And so he was released.

When an account of this unusual single case involving an experimental drug was published later that year, it caused a minor stir in psychiatric circles. Some physicians were eager to test Laborit’s drug. But others were deeply suspicious—both of the whole idea of drug therapy for mental disease (other than putting patients to sleep, there had been an unbroken history of failed drugs) and of Laborit himself. Laborit might be brilliant, but he was also seen as a little too sure of himself, a little too cocky. He had been publishing his successes with RP-4560 in surgery, pushing his artificial hibernation approach. He more than hinted that the drug might have applications in the mental health field. But Laborit was not a psychiatrist, had little training in mental health, and was far from an expert. To the psychiatric leaders in France, he was a surgeon with some odd ideas. What do surgeons know about the human mind?

Still, these were interesting results. RP-4560 trickled out into the medical community, eagerly shared with interested physicians by the drug’s maker, Rhône-Poulenc. Through 1951, RP-4560 was tried on a number of patients with a variety of problems, and a surprising number of them seemed to get better. It helped relieve itching and anxiety in a patient with eczema. It helped stop the vomiting of a pregnant woman. And it seemed to work across a wide range of mental patients: It was tried on neurotics, psychotics, depressives, schizophrenics, catatonics—even patients thought to have psychosomatic disorders. Dosages were guess-and-test; durations of treatment were uncertain. Sometimes the drug did nothing. But many times it helped.

And in some cases, the effects seemed miraculous.

What was needed next were large-scale tests by reputable experts. It was the beginning of a year that one historian of psychology called “The French Revolution of 1952.”

Jean Delay, like Laborit, was interested in the general idea of shock. But his interest focused on the beneficial mental effects of various types of shocks. Shock treatments were all the rage in mental asylums. In 1952 the focus was on electroshock (more properly, electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT). But there were other techniques that used drugs or even induced fevers to create a shock effect. In some cases, for no reasons anyone really understood, these treatments led to striking improvements. But only in some cases. Often shock seemed to do no good at all.

Delay wanted something better. He was an early proponent of ECT. He had seen some severely ill mental patients emerge from ECT sessions much improved and better able to function. But even under the most careful conditions, there were still many failures. And in the early days, ECT was close to barbaric and often dangerous. ECT patients jerked and writhed as the electricity jolted them. Some went into spasms so strong they broke bones. Some died.

Delay, always on the lookout for biological treatments, was also more willing than most psychiatrists to experiment with drugs. His staff tried various chemicals to treat depression and catatonia. Delay personally experimented with LSD soon after its discovery, and in the early 1950s his people tested the effects of mescaline on both normal and psychiatric patients. Drugs were useful tools, Delay believed.

Sainte-Anne was a good place to try new things. One day in late 1951, one of Delay’s top men, Pierre Deniker, walked in with a story about his brother-in-law, a surgeon, who had heard about some new methods for preventing shock that were being tried out at the military hospital. The fellow doing this work, Laborit, reported patients who were calm and passive when cooled and given a cocktail of drugs. The brother-in-law told Deniker, “You can do what you like with them.” And Deniker, like Laborit, thought about treating mental patients with the drug. Perhaps it could help calm the most agitated, confused, and violent among them. Sainte-Anne started testing Laborit’s drug, RP-4560. The first patient was Giovanni A., a fifty-seven-year-old laborer brought in by the police in March 1952, raving and incoherent. He had been creating a disturbance in the streets and cafés of Paris, wearing a flowerpot on his head and shouting nonsense at people. He looked like a schizophrenic, an incurable.

Under Deniker’s supervision, he was given a shot of RP-4560, laid down, and cooled with ice packs. Giovanni stopped shouting. He grew calm, seemed to fall into a daze, as if he were watching everything around him from a distance. He slept. The next day they repeated the procedure. He remained calm as long as he received regular doses of the drug. And he gradually got better. His fits of yelling and babbling became fewer. After nine days he was able to have a normal conversation with his doctors. After three weeks, he was discharged.

No one at Sainte-Anne had ever seen anything like it. It was as if Giovanni had regained his lost sanity—as if Giovanni the incurable had somehow been cured. Deniker quickly tried the new drug on more patients. At first he continued mimicking Laborit’s artificial hibernation approach, cooling the patients with ice packs after their injection, using so much ice that pharmacy services had trouble keeping up. But his nurses, annoyed by the constant attention the ice required, suggested trying RP-4560 without the cooling. They found they didn’t need the ice; with mental patients, the drug alone worked just as well.

The nurses loved RP-4560. One or two shots turned even the most difficult and dangerous patients into meek lambs. Deniker and Delay respected their nurses; they knew they were onto something special with this drug when the head nurse came to them, impressed, and asked, “What is this new drug?” You couldn’t fool nurses.

Delay took a personal interest in the work and was often at Deniker’s side. They expanded their tests. Every case was carefully tracked, the results meticulously charted.

And patterns began to emerge. Yes, RP-4560 helped patients sleep, but not like a standard sleeping pill. It didn’t knock them out. It left them “steeped in sweet indifference,” as Delay put it—conscious, better able to communicate, but distanced from their madness. With that distance often came the ability to reason: Over time, the drug made many patients less mentally confused and more coherent.

They started trying it on the most severe cases at Sainte-Anne, including the incurables, patients who had been locked away for years, suffering from deep depression, catatonia (in which patients stopped moving or responding), schizophrenia, and any sort of psychosis that was not responsive to other therapies. In every case, they noted, the drug had “a powerful and selective calming effect.”

One major problem with the deeply mad was that doctors could simply not talk to them. Without that communication, therapies were limited. The real revolution began as many Sainte-Anne patients—not all, but many—began to talk with their doctors. Their wits had returned. RP-4560 did more than calm patients down. It “dissolved delirium and hallucinations,” one physician marveled. “We were astonished and fired with enthusiasm by these results,” remembered another.

Almost as important as the effect on patients was the effect on the staff. Asylum doctors and nurses, accustomed to constant noise in the back wards, punctuated by outbursts and screams, found themselves in a new world, a much quieter, calmer place where progress was possible. Accustomed to accepting that many of their patients would never be cured, they suddenly found themselves able to communicate, to move cases forward, to give patients hope.

The most touching incidents involved incurables who had been locked away for years, fated to die in the asylum. When they got their first shots of RP-4560 and began to regain their senses, it was as if Rip Van Winkle were waking up. When they were, for the first time in years, able to talk, and were asked, “What year is it?” they would answer with the long-ago date when they first came to Sainte-Anne. Now they rejoined the world, understood what had happened to them, began to communicate, to listen to something other than the voices in their heads, to take part in occupational therapy, to talk through their problems. They began to heal.

These effects were so stunning that no one outside of Sainte-Anne would have believed them if Delay hadn’t announced they were real. Delay’s intellectual eminence and reputation for careful research commanded attention. He delivered his first results with RP-4560 on a fine spring day in 1952, in the elegant mansion of the Académie Nationale de Chirurgie on the Rue de Seine. Curiosity was intense, and the audience included most of France’s top psychiatrists and psychologists. Delay delivered a clear and elegant talk that astounded his listeners and ignited a firestorm of interest.

Somewhat oddly, although he credited the work of several other early researchers, Delay did not mention Laborit’s name. Laborit and his colleagues at the military hospital were offended by the slight, which became the start of a small personal and professional battle for scientific credit that smoldered for years. The fact was that they both deserved credit: Laborit spurred the creation of RP-4560 and suggested its value; Delay’s work legitimized it for psychiatric care and introduced it to the world.

Between May and October 1952, Delay and Deniker published six articles detailing their early tests on dozens of patients suffering from mania, acute psychosis, insomnia, depression, and agitation. A picture emerged: This was an important new advance for the treatment of some, but not all, mental disturbances. It was especially valuable in the treatment of mania, confusion, and possibly schizophrenia. But it did not work for depression. And, like all drugs, it had side effects: Too much given over time could leave patients too drowsy, too indifferent, too unemotional—it could make them into zombies.

More and more physicians began asking for samples of the experimental drug, and Rhône-Poulenc was happy to oblige. It was tested throughout France, then spread into the rest of Europe. Reports came back of a startlingly wide range of effects, many of them outside of psychiatry. As Laborit had found, it was good in prepping patients for surgery and seemed to boost the effects of anesthetics, making it possible to lower their doses. It was an aid in sleep therapy, eased motion sickness, helped calm the nausea and vomiting of expectant mothers. And everyone agreed that it appeared to be remarkably safe.

Rhône-Poulenc wasn’t quite sure what to do with all this good news. RP-4560 did so many things that the company couldn’t decide how to market it. So they put it on the market in the fall of 1952 under the vague heading of “a new nervous system modifier,” a bit like a narcotic, a bit like a hypnotic, a sedative, a painkiller, an anti-vomiting drug, and a booster of anesthetics rolled up into one. All this, plus there were positive effects on mental illness. It was good for surgeons, obstetricians, and psychiatrists alike. What kind of trade name do you use for a drug like that? Something vague, something hinting at big things. So it was released as Megaphen in France and Largactil (“large action”) in the United Kingdom. But most physicians called it by its new chemical name, chlorpromazine (CPZ).

Psychiatrists and other mental health workers had been waiting for decades for their miracle drug, something that would do for mental illness what antibiotics did for infections, antihistamines did for allergies, and synthetic insulin did for diabetes. CPZ looked like what they had been waiting for.

This all happened before adequate animal tests were done, before any knowledge of how CPZ worked in the body, and without knowing whether, in the long term, it would prove safe.

Rhône-Poulenc sold the American rights to their new drug to Smith, Kline & French (SKF), an aggressive, up-and-coming drugmaker. SKF got it ready for testing by the FDA. “They were so smart,” one researcher said of the company’s work. SKF submitted it to the FDA for the treatment of nausea and vomiting, saying nothing about mental health. That made approval a slam dunk; the FDA gave it a thumbs-up within weeks of submission in the spring of 1954. Once it was FDA approved, and thus deemed safe, physicians were free to prescribe the drug for whatever they wanted (this practice of “off-label” prescribing would become an important part of marketing many other drugs). SKF trade-named it, somewhat vaguely, Thorazine. And they began pushing hard for its use in mental hospitals.

SKF’s job now was to sell the new drug not to the public, but to America’s doctors. They put everything they had into it, launching a marketing blitz that became something of a legend. They flew Delay and Deniker over from France to give talks; created a fifty-member task force that organized medical meetings, lobbied hospital administrators, and put on events for state legislatures highlighting the possible use of the drug in lowering the asylum load. They made sure every new journal article noting positive effects for CPZ got a wide reading, encouraged research, and even produced a TV show, The March of Medicine, in which the president of SKF himself talked about the new drug’s effects.

Thorazine “took off like a shot,” one of SKF’s directors remembered. SKF’s PR department went into overdrive, pushing out the word to newspapers and magazines. “Wonder Drug of 1954?” a Time magazine story asked. The enthusiasm was fueled by real-world experience. Stories flew from doctor to doctor. There was the mental patient who hadn’t said a word for thirty years, and after two weeks on Thorazine told his caregivers that the last thing he remembered was going over the top of a trench in World War I. Then he asked his doctor, “When am I getting out of here?”

“That,” his doctor said, “was an honest-to-God miracle.”

There was the physician who read the journals, saw the drug work, then took out a second mortgage on his house and put all the money into SKF stock. It was a good investment: The new drug was a blockbuster. By 1955, Thorazine alone accounted for one-third of SKF’s sales; the company had to go on a hiring spree and put up new production facilities to keep up with demand.

It was just a taste of what was coming. In 1958, Fortune magazine ranked SKF the number two corporation in America for net after-tax profit on invested capital. Its revenues shot up more than sixfold between 1953 and 1970, with Thorazine bringing in the lion’s share of the money. The company pumped a good part of that profit back into research, building a state-of-the-art lab to find more mind drugs. Other companies did the same.

And mind drugs were suddenly everywhere. The term “mind drugs” as used in this book does not encompass every substance that can affect your mood or mental state, a roster that could include everything from your morning coffee to your evening cocktail, along with just about every street drug you can buy. The new mind drugs, the ones that first showed up in the 1950s, are legal drugs developed by pharmaceutical companies specifically to relieve mental disorders.

CPZ was the first, in 1952, becoming the first of a family of drugs we now call “antipsychotics.” It was followed in short order by Miltown, the first everyday tranquilizer for treating minor anxiety, in 1955. Miltown was found by accident, when a researcher looking for a preservative for penicillin noted that some of his test rats were looking very relaxed. It became a sensation in the United States, a “martini in a pill” that could take the edge off stress, and it was quickly picked up by Hollywood stars—within a few years Jerry Lewis was making jokes about Miltown when he hosted the Oscars—high-level executives, and suburban wives. Other “minor tranquilizers” like Librium and Valium soon followed, the start of a popular craze for the pills the Rolling Stones called “Mother’s Little Helper.”

Then a Swiss researcher, working in the early 1950s on a cure for tuberculosis, noticed that some of his ill, depressed TB patients were dancing in the halls after they took one of his experimental drugs. It was called iproniazid, and it became one of the first antidepressants, hitting the market in the late 1950s and opening the door for Prozac and a flood of other antidepressants through the 1980s and 1990s.

Suddenly psychiatrists, who just a few years earlier had no drugs to get at the worst symptoms of mental disorders, had several new families of drugs to choose from. A whole new area of research, psychopharmacology, arose. Pushed by the kind of aggressive marketing to physicians that SKF had perfected with Thorazine, these new drugs all had their moments in the sun as they went through their Seige cycles—tranquilizers became signature drugs of the 1960s and 1970s; antidepressants bloomed into blockbuster drugs in the 1980s and 1990s; and the growing family of antipsychotics, which today includes Seroquel, Abilify, and Zyprexa, rank today among America’s top-selling drugs.

Why did all of these mind drugs suddenly appear in the 1950s? Perhaps it had something to do with society’s need to deal with the pain and stress of World War II, or the desire to escape from the conformity of the Eisenhower era. Whatever the reasons, the new mind drugs changed American attitudes toward taking pills. Now pharmaceuticals were not something you took only to battle a serious health problem: Now they were something you took after work to chill out, or over time to change your ability to cope with everyday reality. The mind drugs of the 1950s set the stage for the next wave of recreational drugs in the 1960s, when popping more colorful, more mind-expanding hallucinogens became a craze. Mind drugs changed American culture.

And they certainly revolutionized mental health care. SKF’s PR blitz for Thorazine helped make the drug a huge hit in public mental hospitals. At first psychiatrists had been slow to accept it, believing that no pill could really solve mental problems, that the road to mental health had to run through Freud and talk therapy, not drugs. Many psychiatrists argued that Thorazine simply masked the underlying problems, it didn’t fix them. A split began to rupture the mental health community, with psychotherapists—followers of Freud, often in private practice, dealing with one patient at a time, often well paid—on one side, and asylum doctors—often in a public hospital, less well paid, and dealing with scores or hundreds of patients—on the other. The Freudians were in charge of much of the professional infrastructure for psychiatry in the 1950s, and “I can tell you the pioneers in psychopharmacology were looked upon as quacks and frauds,” one of the drug pioneers said. “I was accused of being no different than the guys who sold snake oil in the Wild West days.” The idea that a pill could be used to treat an organ as complex, as mysterious, as finely tuned as the human brain was unbelievable. Those who promoted such unbelievable chemical cures seemed no better than the old patent drug salesmen hawking their wares at small-town medicine shows.

It was the asylum doctors who really appreciated what CPZ could do. It was a breakthrough drug, something truly new, something that offered hope. As deeply ill patients became able to talk for the first time since their disease started, they told their caregivers things like “I can cope with the voices better” and “it brings me back into focus.” While they might still hear voices and suffer from delusions, these symptoms didn’t bother them as much. They could now talk about what they were experiencing. They could function.

As CPZ use spread, the straitjackets went into cupboards. Patients who were unreachable began to open up. One physician remembered a catatonic patient, a man who had spent years silently twisted into a strange posture that resembled an owl, getting a regimen of the drug. After a few weeks he greeted his doctor normally, then asked for some billiard balls. When he got them, he began juggling.

“Look, you can’t imagine,” said another early adopter. “You know we saw the unthinkable—hallucinations, delusions eliminated by a pill! . . . It was so new and so wonderful.” By 1958, some mental health hospitals were spending 5 percent of their budgets on CPZ.

And then came the exodus.

For two centuries, the number of patients in asylums had risen inexorably. But in the late 1950s, to almost everyone’s surprise, for the first time in history, the numbers started going down.

The two reasons were drugs and politics. The drugs, of course, were CPZ and all the copycat antipsychotics that followed. With them, doctors could keep patients’ symptoms under control enough to allow them to leave the hospitals and return to their families and communities. Many were able to hold down jobs. Unlike opiates or sleeping pills, the new drugs were just about impossible to overdose on. Nobody would want to anyway, because antipsychotics do not make you euphoric. They simply allowed patients to tamp down their symptoms enough to function. None have ever been drugs of abuse. So instead of being housed for years in an asylum, patients could now be diagnosed, treated, given a prescription, and released.

The politics came from state and county budget-makers, who had long worried about the mushrooming costs of public mental health facilities. Getting patients out of the asylums and mental hospitals was a win-win: Patients got to live their lives, and taxpayers got out of paying a tremendous bill. If the asylums shrank, so would the tax burden. Money would be freed for other programs. Some would go to community-based counseling, which would keep in touch with the newly released patients, make sure they kept up on their drugs, and (it was hoped) track their success integrating back into society. The rest could be used for other priorities, like education.

The era of community-based mental health care started, and the old mental hospitals emptied. Thousands of patients were released every year, many carrying a prescription for CPZ. In 1955, there were more than a half-million patients in U.S. state and county mental health hospitals. By 1971, the number had been cut almost in half. By 1988 it was down by more than two-thirds. The giant old asylums on their green grounds were torn down or turned into luxury hotels.

The first years of this shift were a very strange time. Physicians who thought they’d never be able to help schizophrenic patients were watching them walk back into lives outside. Schizophrenic patients who never imagined leaving the asylum suddenly found themselves trying to piece together lives that had been shattered years earlier.

It was rarely easy. Suddenly patients were released, one physician remembered, to find that their husbands and wives were married again, that they had no jobs, that their ability to cope, while improved, was not what it was before they went in. Everything depended on taking their meds; if they did not, increasing numbers ended up back on the streets. While many newly released patients managed to successfully integrate back into their homes and communities, others did not. The situation was made worse when government agencies didn’t adequately fund much needed community mental health efforts.

The exodus grew after 1965, when new Medicare and Medicaid programs offered coverage for nursing home care but not for specialty psychiatric care in state mental hospitals. That meant that tens of thousands of elderly mentally ill patients, many with Alzheimer’s, were moved out of mental hospitals and into nursing homes, with the cost of their care shifted from state to federal budgets. The use of antipsychotics in nursing homes shot up. So did Medicare costs.

The dream of integrating mental patients back into society began fraying at the edges. Increasing numbers of younger patients, especially those who found themselves unable to live with their families, ended up housed in jail. More than half of male prisoners today, according to one recent survey, have been diagnosed with mental illness, along with three-quarters of female prisoners. Mentally ill homeless people can be seen on the streets of every American city and many smaller towns.

We’re still dealing with the fallout. The number of beds in public mental health hospitals—designed to be available to poor people—has declined dramatically. At the same time, the number of beds in private mental health facilities—for the wealthy—have shot up.

CPZ changed the very soul of mental health care. In 1945, about two-thirds of the patients at Houston’s Menninger Clinic took part in psychoanalysis or psychotherapy. In 1969, only 23 percent did. In the 1950s, most American medical schools had a few part-time psychiatrists on their faculty, and those few were often thought of as something akin to woolly-headed witch doctors by the rest of the professors. Today every American medical school has a full department of psychiatry.

Not that many people see a psychiatrist anymore. You don’t need to in order to get a prescription for a mind drug. In 1955, just about anyone who went to their local doctor with a serious mental problem was referred immediately to a psychiatrist (who would likely put them into analysis). Today, most general practitioners are willing and often able to diagnose the problem themselves and prescribe a pill. In the 1950s, schizophrenia was blamed on bad parenting, emotionally cold “refrigerator mothers,” and the home environment. Today, it’s seen as a biochemical dysfunction that has little to do with parenting. In 1955, people with minor anxiety, minor depression, standard-issue worries or behavioral problems, trouble paying attention, or any of a thousand other minor mental problems, were expected to work through their issues with the help of their families and friends. Today, most of them take drugs.

For good or ill, CPZ changed it all.

In the ten years after it first reached the market, CPZ was taken by fifty million patients. But today it’s hardly used at all.

It’s been superseded by new formulations that have taken over the market, an evolution fueled by CPZ’s negative side. The more the older drug was used in the 1950s and 1960s, the more patients started turning up with strange side effects. There was the “purple people” issue, when the skin of high-dose patients turned a strange sort of violet-gray. Others got rashes or developed sun sensitivity. In some, blood pressure would drop precipitously. Others developed jaundice or blurred vision.

These were relatively minor. Side effects were expected with any new drug, and most of CPZ’s could be fixed with proper dosing. But then came something more troubling. Physicians around the world found that some of their long-term patients, maybe one in seven, again mostly those on higher doses, were getting twitchy, their tongues poking out uncontrollably, lips smacking, hands shaking, faces twisted into grimaces. They couldn’t seem to stop moving, shifting from foot to foot, rocking in place. They walked with a jerky gait. It looked to some physicians like symptoms of encephalitis or Parkinson’s disease. The condition, named tardive dyskinesia, was very serious. Even when the doctors lowered their doses, the symptoms could persist for weeks or months. In some patients they didn’t go away even when the drug was stopped entirely.

So major drug companies searched for the next big antipsychotic, something that could do what CPZ did, but with added benefits and fewer side effects. There were twenty on the market by 1972. But none of this first wave was more than marginally better than the drug used by Laborit and Delay.

In the 1960s Jean Delay was at the height of his career. His work with CPZ had changed the world of medicine, he was widely respected, and he was being showered with a growing list of honors.

Then, on May 10, 1968, it all came tumbling down. Paris’s May Revolution brought thousands of student revolutionaries into the streets, and some of them decided to take over Delay’s office at Sainte-Anne. The students believed that madness was not so much biological, as Delay thought, as it was a social construct used to enforce conformity. Delay symbolized the establishment, powers that used CPZ like a “chemical straitjacket” to control anybody they deemed undesirable. Delay was everything that was wrong with psychiatry and society. The students pushed into the great man’s office and shouted their ideas at him, emptied his desk drawers, tossed his papers in the air, and refused to leave. They occupied Delay’s rooms for a month. Rumors said that they stripped his diplomas and awards from the wall and sold them as war booty in the square of the Sorbonne (when in fact one of his daughters had gone to his office and talked a student guard into letting her take most of them home). When Delay tried to lecture, they sat in the hall, playing chess and making rude comments. It was a humiliating public repudiation of his life’s work.

It broke him. Delay gave up his position and never went back.

Laborit, in his own way, flourished. He never got over his resentment of Delay’s downplaying his work with CPZ, a grudge he held for the rest of his life. But he went on to earn many honors of his own—including the Lasker Award for medicine, second in prestige only to the Nobel Prize—and became something of an outspoken hero, his hair modishly long, his comments on psychiatry free-flowing, his Gallic good looks earning him a moment as a movie star when he played himself in Alain Resnais’s 1980 film, Mon Oncle d’Amérique.

The antipsychotics did more than empty the asylums and change the practice of psychiatry. They opened the door to studies of the brain that are continuing to shake our ideas of who we are.

The big question through the 1950s was: How does CPZ do what it does? It took a decade of research and a major change in how we view brain function to find the answer.

Before CPZ, most researchers viewed the brain as an electrical system, like a very complex switchboard with messages flashing over the wires (nerves). Things went wrong when the wires got messed up. Treatments like ECT could reboot the system. Lobotomies could cut out a faulty section of wiring.

After CPZ, scientists realized that the brain was less like a switchboard and more like a chemical laboratory. The trick was to keep the molecules in the mind in proper balance. Mental illness was redefined as a “chemical imbalance” in the brain, with shortages or surpluses of one chemical or another. Mind drugs worked by restoring the chemical balance.

Many years of intensive research showed that CPZ altered the levels of a class of molecules called neurotransmitters, which are essential in moving impulses from one nerve cell to the next. By using drugs like CPZ as tools to study brain chemistry, researchers have now identified more than one hundred different neurotransmitters; CPZ affected levels of dopamine and several others. Researchers at other drug companies began finding more antipsychotics that affected different arrays of neurotransmitters to varying degrees.

In the late 1990s a new string of antipsychotics began to appear with trade names like Abilify, Seroquel, and Zyprexa. These “second generation” antipsychotics weren’t all that different than the first ones, including CPZ, but they did offer a somewhat lower risk of tardive dyskinesia. They were very effectively marketed as a great breakthrough. And, because they were somewhat safer, more doctors felt comfortable giving them to more patients and often prescribed off-label for conditions for which they had never been FDA approved: PTSD in veterans, eating disorders in children, anxiety and agitation in the elderly. Nursing homes, prisons, and foster homes began using the drugs to keep their charges quiet and under control. By 2008 antipsychotics had grown from a specialty drug used almost exclusively by severely ill mental patients to the bestselling class of drugs in the world.

The more mind drugs like CPZ were studied, the more they helped open up the chemical mysteries of the brain. And the more we learn about the breathtakingly complex brains we carry around, the less we seem to know. The human brain is the one system in the body that makes the immune system look simple. We’ve barely begun the long journey to understanding consciousness.

Perhaps more important, from a cultural angle, is how these drugs have changed our sense of who we are and how we relate to medicine. If our moods, our emotions, our mental abilities are simply chemical in nature, well, then we can change all that with chemistry. With drugs. Our mental states are no longer who we are. They are symptoms that can be treated. If we’re anxious, we can take a drug for that. If we’re depressed, we can take another. Trouble concentrating? Another.

Of course, it’s not that simple. But many people are acting as if it is.