![]()

National Singing Styles

Divers Nations have divers fashions, and differ in habite, diet, studies, speech and song. Hence it is that the English doe carroll; the French sing; the Spaniards weepe; the Italians…caper with their voyces; the others barke; but the Germanes (which I am ashamed to utter) doe howle like wolves.

–Andreas Ornithoparcus, Musicæ active micrologus (1515), translated by John Dowland, 1609

As to the Italians, in their recitatives they observe many things of which ours are deprived, because they represent as much as they can the passions and affection of the soul and spirit, as, for example, anger, furor, disdain, rage, the frailties of the heart, and many other passions, with a violence so strange that one would almost say that they are touched by the same emotions they are representing in the song; whereas our French are content to tickle the ear, and have a perpetual sweetness in their songs, which deprives them of energy.

–Marin Mersenne, Harmonie universelle, 1636

Although one might assume that the human voice has not changed over the centuries, many elements of seventeenth-century vocal performance practice differed considerably from modern singing. There was no single method of singing seventeenth-century music; indeed, there were several distinct national schools, each of which evolved during the course of the century. The differences between French and Italian singing were widely recognized in this period, and the merits of each were debated well into the eighteenth century.1 There were also distinctive features in German, English, and Spanish singing.

Though the Italian school was the most influential outside its borders, much less source material by Italians survives than by Germans. In reading the sources, confusion inevitably arises regarding terminology and the repertories and regions to which it is applied. Writers use the same term, such as tremolo, with different meanings, which in turn may not correspond to modern usage. Though laryngology was not an established science in the seventeenth century, some writers ventured into the area of vocal physiology, frequently creating more confusion than clarification.

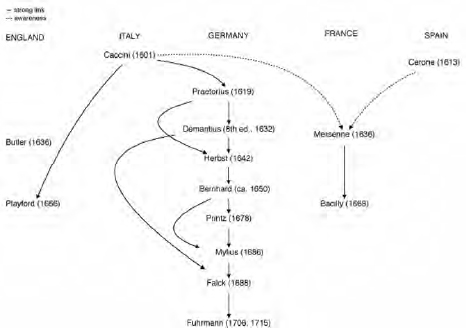

FIGURE 1.1. Linkage of selected seventeenth-century singing treatises.

Examining the linkages among treatises reveals both continuity and evolution within a national style over time and crosscurrents among regions. Figure 1.1 shows this linkage for Italian and German sources. While there was considerable musical exchange between Italy and Germany, there are still characteristics that give the music and its performance style an Italian or German “accent.”

Most of the defining characteristics of national styles of singing derive from language.2 As Andrea von Ramm has observed,

The characteristic sound of a language can be imitated as a typical sequence of vowels and consonants, as a melody, as a phrasing. There is an established rhythmical impulse of a language and a specific area of resonance involved for this particular character of a language or a dialect. In German one can say instead of ‘Dialekt’ also ‘Mundart.’…This causes a different sound, a different resonance and a different singing voice, depending on the language sung.3

Seventeenth-century writers on singing also recognized the importance of language. Christoph Bernhard discussed Mundart at some length in Von der Singe-Kunst oder Manier:

The first [aspect of a singer's observation of the text] consists in the correct pronunciation of the words…such that a singer not rattle [schnarren], lisp or otherwise exhibit bad diction. On the contrary, he ought to take pains to use a graceful and irreproachable pronunciation. And to be sure in his mother tongue, he should have the most elegant Mund-Arth, so that a German would not speak Swabian, Pomeranian, etc, but rather Misnian or a speech close to it, and an Italian would not speak Bolognese, Venetian or Lombard, but Florentine or Roman. If he must sing in something other than his mother tongue, however, then he must read that language at least as fluently [fertig] and correctly as someone born to it. As far as Latin is concerned, because it is pronounced differently in different countries, the singer is free to pronounce it as is customary in the place where he is singing.4

The importance of Mundart makes it essential to open the Pandora's box of historical pronunciations, which in their specifics are beyond the scope of this essay. While Italian (a language full of dialects) has changed little in its pronunciation in the last four centuries, French and English have changed profoundly. As a literary language, German was in its infancy in the seventeenth century; it did not achieve a standardized pronunciation for the theater until the late nineteenth century. Even the same language, such as Latin, was pronounced differently in different places (and still is). Research in historical pronunciations yields many revelations in the poetry and expands the palette of sounds available to the aural imagination.5

The singer's art was closely aligned with the orator's during the Baroque period. The clear and expressive delivery of a text involved not only proper diction and pronunciation, but also an understanding of the rhetorical structure of the text and an ability to communicate the passion and meaning of the words. How this was achieved differed according to the particular characteristics of the language and culture as well as the musical style. The swing of the pendulum between the primacy of the words and the primacy of the music that occurred during the seventeenth century is important to bear in mind as we survey singing in Italy, France, Germany, England, and Spain.

ITALY, CA. 1600-1680

During the 1580s and 1590s, florid singing in Italy reached a zenith with singers who excelled in the gorgia style of embellishments. These singers included women, boys, castratos, high and low natural male voices, and falsettists. The term gorgia (= throat) identified the locus of this technique, involving an intricate neuromuscular coordination of the glottis, which rapidly opens and closes while changing pitch or reiterating a single pitch, an action that is apparently innate to the human voice.6 A basic threshold of speed is required in order for throat articulation to work easily. The glottal action can be harder or softer depending on the degree of clarity and the emotional expression desired;7 the Italians apparently used a harder articulation than the French. In 1639 André Maugars observed that the Italians “perform their passages with more roughness, but today they are beginning to correct that.”8 Throat articulation works best when the vocal tract is relaxed and there is not excessive breath pressure.9

Lodovico Zacconi described gorgia singers as follows:

These persons, who have such quickness and ability to deliver a quantity of figure in tempo with such velocity, have so enhanced and made beautiful the songs that now whosoever does not sing like those singers gives little pleasure to his hearer, and few of such singers are held in esteem. This manner of singing, and these ornaments are called by the common people gorgia; this is nothing other than an aggregation or collection of many eighths and sixteenths gathered in any one measure. And it is of such nature that, because of the velocity into which so many notes are compressed, it is much better to learn by hearing it than by written examples. 10

In Italy, throat-articulation technique was often referred to as dispositione.11 There is ample evidence that it was carried over with the advent of monody and the new, more declamatory styles of singing, in spite of changes in ornamentation style and vocal technique. We find ornaments, such as the ribattuta di gola (“rebeating of the throat”), for example, whose very name suggests its performance technique. Giulio Caccini described the trillo, a repercussion on one pitch, as a “beating in the throat.”12

Learning a repercussion ornament was recognized as a good way to master throat articulation. Caccini remarks that the trillo and gruppo are “a step necessary unto many things.”13 It is in this context that we should understand Zacconi's remark that “the tremolo, that is, the trembling voice, is the true gate to enter the passages [passaggi] and to become proficient in the gorgia.”14 Equating Zacconi's tremolo with pitch-fluctuation vibrato, as some scholars have done, contradicts the nature of throat-articulation technique.15 I understand his reference to the continuous motion of the voice to refer to the rapid opening and closing of the glottis, which in the trillo is done continuously on one note. Learning this glottal action independent of changing pitch is enormously helpful as a first step, before advancing to passaggi and other ornaments involving rapid changes of pitch. As Zacconi says, it indeed “wonderfully facilitates the undertaking of passaggi.”16 It is impossible to use throat articulation and continuous vibrato simultaneously, because the two vocal mechanisms are in laryngeal conflict with each other. Because Zacconi's remarks so clearly refer to the gorgia style, it is highly unlikely that his tremolo signifies either pitch-fluctuation vibrato or intensity vibrato.17

The decision to use throat-articulation technique has a direct bearing on other stylistic decisions beyond the issue of vibrato. Because of the innate neuromuscular speed involved, the technical choice of throat articulation is directly linked to decisions regarding tempo. Given the fairly narrow physiological range of possible speeds, we can gauge the tempo range for pieces using throat articulated passaggi reasonably accurately.18

The declamatory style of singing developed by singer-composers such as Jacopo Peri and Caccini extended speech into song. It most likely involved a laryngeal setup known today as “speech mode,” in which the larynx is in a neutral position, with a relaxed vocal tract and without support from extrinsic muscles. Speech mode would have easily accommodated the continued use of throat articulation. What was new, compared to Renaissance practice, was the role (and style) of ornamentation in expressing the text and the use of a more flexible breath stream to reflect the increasing exploitation of the qualitative nature of the Italian language. This flexible breath stream would have ebbed and flowed with the accentuation of the text.19

The increased interest in the qualitative nature of Italian is tied to the development of the stile rappresentativo. Musical rhythms evolved from the characteristic rhythms associated with different poetic line lengths and poetic feet. Singers were highly sensitive to the different dynamic stresses for the verso piano, verso tronco, and verso sdrucciolo.20 As Ottavio Durante says in the preface to his Arie devote (1608), “You must pay attention to observe the feet of the verses; that is to stay on the long syllables and to get off the short ones; for otherwise you will create barbarisms.”21 Giovanni Battista Doni, in his Trattato della musica scenica (1633-35), defined three levels of speech in the stile recitativo: narrative, expressive recitative, and special recitative (a style in between the other two), each of which had its own subtly different characteristic style of speech, compositional style, and manner of singing.

Consistent with the extension of speech into singing was the relatively narrow vocal compass of much of the music in the new style in the early decades of the century and the general preference for “natural” register rather than falsetto. Caccini was quite explicit: “From a feigned voice can come no noble manner of singing, which only proceeds from a natural voice.”22 Bellerofonte Castaldi, in his preface to Primo mazzetto di fiori (1623), wrote:

And because they treat either love or the scorn which a lover has for his beloved, they are represented in the tenor clef, whose intervals are proper and natural for masculine speech; it seems laughable to the Author that a man should declare himself to his beloved with a feminine voice and demand pity from her in falsetto.23

Falsettists certainly were common in church choirs24 and were preferred to less skilled boys for solo parts.25 The overriding conclusion to make from Caccini's comment is not to switch registers within the same piece but to transpose, if necessary, to avoid doing so. This is basically a one-register concept. For the new style of the early seventeenth century, the falsettist was not yet the operatic voce mezzana.26

Different voice registers had been recognized as early as the Middle Ages. In the Lucidarium (1318), for example, Marchettus of Padua mentions three registers: vox pulminis, vox gutturus, and vox capitis.27 Jerome of Moravia, in the Tractatus de musica (after 1272), identifies vox pectoris, vox gutturis, and vox capitis.28 Yet many questions persist regarding the concept of register in the seventeenth century, namely: (1) Were different voice registers used or mixed within the same piece? (2) If so, how many registers were recognized? (3) What was the nature of the transition from one register to another? (4) What was the quality of each register? and (5) How do these early terms relate to modern concepts of register?

Most seventeenth-century writers discuss only two registers, natural and falsetto; Zacconi, however, discusses three: voce di testa, voce di petto, and a mixture of the two, called voce obtuse. He generally prefers the voce di petto to the voce di testa.29 The need to develop a smooth passage between registers is not addressed in Italian sources before Pier Francesco Tosi's Opinioni (1723). Of primary importance to early seventeenth-century Italians was the distinction between “natural” register and “falsetto.”

Another aspect of the new style of Italian singing involved greater attention to subtle dynamic shadings and colorings of the voice to express the text. The new flexible airstream facilitated the greater use of dynamics, especially in ornaments such as the messa di voce (a gradual crescendo and diminuendo) and esclamatione (the inverse). The crescendo was not necessarily correlated with pitch-fluctuation vibrato, as is often the case today. Durante tells us to make a crescendo on the dot and in ascending chromatic progressions.30

In the absence of dynamic indications in the music, the rhetorical structure of the text and the qualitative ebb and flow of the Italian language provide a dynamic chiaroscuro from which one can shape a flexible dynamic plan. However, it is important to bear in mind the underlying dynamic shape of the voice, which I call the “vocal pyramid,” a concept for multiple voices that dates back as far as Conrad von Zabern (De modo bene cantandi, 1474).31 In this “pyramid” the lowest voices are fuller and heavier, the highest voices softer and finer. This is a balance somewhat different from what we often hear today, when choirs are somewhat “top-heavy.” Hermann Finck articulated this concept in a polyphonic context in his Practica musica (1556): “A discant singer sings with a tender and soothing voice, but a bass with a sharper and heavier one; the middle voices sing their melody with a uniform sound and pleasantly and skillfully strive to adapt themselves to the outer voices.”32

As solo singing developed, Italian singers incorporated this choral-sound concept into the individual voice. Singers today are generally taught to phrase to the highest point of the musical line, whereas in text-centered music of the early Baroque, the rhetorical stress customarily takes advantage of the greater strength of the lower range. This became more fully developed later in the century as compositional practice utilized a more expanded vocal range. The “pyramid” has enormous implications both for dynamics in general and for the dynamic shape and direction of each phrase.

Another important characteristic of the new style was a certain rhythmic freedom, called sprezzatura. The singer was relatively free to depart from a regular tempo and from the notated musical rhythms in order to inflect the text. Rodolfo Celletti describes sprezzatura quite aptly:

It signifies a kind of singing liberated from the rhythmic inflexibility of polyphonic performance and allowing the interpreter, by slowing down or speeding up the tempo to “adjust the value of the note to fit the concept of the words” and hence to make the phrasing more expressive.33

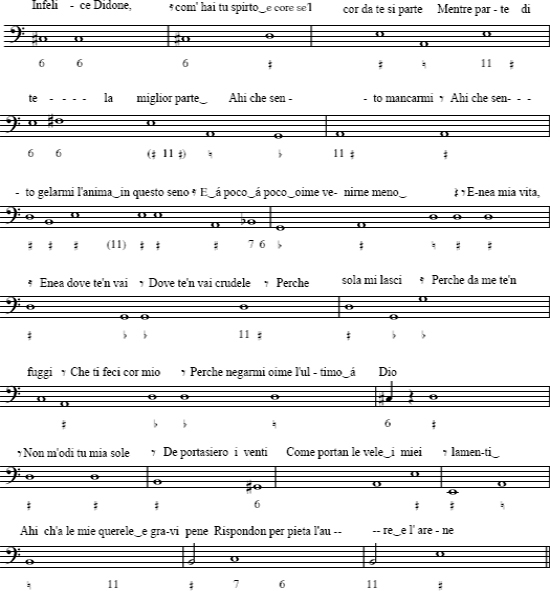

Modern singers, trained to sing with absolute rhythmic precision, need time to become comfortable with the concept of sprezzatura. The easiest way to incorporate it into singing is by first declaiming the text in an impassioned way as an orator or actor might. When I am not singing from memory, I often use a small prompt book with the texts set out according to the poetic lines, so that I can see the text as poetry freed from the musical notation. Sprezzatura can be equally daunting to a continuo player used to counting measures. In Ensemble Chanterelle, a group with which I perform regularly, theorbist Catherine Liddell has developed a notation system for works in stile recitativo, shown in Example 1.1, which reproduces only the singer's text and the bass pitches corresponding to the correct syllables, without any durational values (plus any necessary figures and some shorthand reminders about chord arpeggiation). This allows me total rhythmic freedom, frees her from unnecessary visual information, and enables both of us to make each performance responsive to the inspiration of the moment.

Perhaps the overriding characteristic of Italian singing in the first part of the century was the passionate engagement of the singer with the music, which in turn engaged the audience. Marco da Gagliano described hearing Jacopo Peri:

No one can fully appreciate the sweetness and the power of his airs who has not heard them sung by Peri himself, because he gave them such grace and style that he so impressed in others the emotion of the words that one was forced to weep or rejoice as the singer wished.34

This passionate engagement becomes all the more important today when performing for an audience (mostly) unfamiliar with the language, the poetry, the music, and the style.

The changes in Italian singing that took place in the generation after Caccini and Peri are closely tied to the rise and influence of the castratos and to the stylistic developments in the opera and the cantata that altered the balance between text and music. These changes did not happen overnight and were by no means complete by the end of the seventeenth century, but they were well established by musical developments in Rome and Venice. They involved greater divisions among recitative, arioso, and aria; greater pictorialization of ornamentation to depict or idealize particular words; changes in the shapes, ranges, and character of the vocal lines; and more generalized (and less nuanced) emotional states portrayed in the aria. In the process, speech gave way in the aria to lyricism and spectacle; subtlety gave some ground to sonority; and singers became virtuosos of the highest order. Venetian opera in particular glorifed the art of singing.35

EXAMPLE 1.1. Excerpt from Sigismondo d'India, Lamento di Didone (1623), illustrating a notation system devised by a skilled continue player, Catherine Liddell, for works in stile recitative. It reflects performance decisions made in rehearsal. This is most apparent with respect to tied and untied notes in the bass that depart slightly from the original notation, and with respect to words that are subject to elision and have been deliberately separated by the singer for dramatic reasons.

Some explanation of the markings in the score:

( ) around figured bass signs indicates that the pitches in parentheses are covered in the vocal part.

- is used in the text (1) to indicate when a bar line or a bass note occurs in the middle of a syllable, (2) to indicate a long(er) note in the vocal part, (3) to provide a visual cue to signal a chord with a special affect, or (4) to signal a consonantal cue by the singer.

![]() alerts the continuo player to either a place of elision in the text or an antici-pazione della syllaba at cadential points.

alerts the continuo player to either a place of elision in the text or an antici-pazione della syllaba at cadential points.

The Teatro dei Barberini and the Venetian public theaters were larger than the halls of noble palaces where opera had its first performances,36 but still significantly smaller and with smaller orchestral forces than we normally find today. The Venetian opera “orchestra” often consisted of only two violins and a large continuo group, thus putting more focus on the singers.37 Castratos, with their penetrating sound quality, wide ranges, large breath capacity, and extensive musical training, were ideal voices for the theater.38 The hermaphroditic quality of their voices gave them the ability to play both male and female roles.

There are characteristics of the castrato voice that we will never be able to duplicate in our time, even though the last castrato, Alessandro Moreschi, sang in the Sistine Chapel until 1913. Modern technology has enabled us to hear an electronic synthesis of the voices of soprano Ewa Mallas-Godlewska and countertenor Derek Lee Ragin, used in the 1995 movie Farinelli, in an attempt to approximate a castrato voice. Whatever one thinks of the results, this is obviously not a viable solution for live performance. The question of what voice type is the best substitute for a castra-to―a male falsettist, a female mezzo-soprano, or a female soprano-is still open to debate.39

Composers capitalized on the wide ranges of the castratos, which in turn led to an expansion of range in every voice type. At the top of their ranges, castratos rarely went higher than a”.40 Lyric, low, coloratura bass voices, such as the Demon in Stefano Landi's Sant'Alessio (1631), traversed C up to f”. While the tessituras on the whole seem to us now to be generally low, range became an important aspect of character delineation. Although higher voices of castratos and females were generally preferred, bass voices were also given important roles, while the tenor voice was largely neglected.

In the absence of a mid-century Italian source on singing as comprehensive as Tosi's Opinioni of 1723, the music itself can provide clues to the evolution of vocal technique. In order to accommodate the wider ranges, singers likely used more than one vocal register. Falsetto and head voice would have been necessary to achieve the upper extension of the range. For female singers, head voice alone may have sufficed, though there is nothing from a laryngeal point of view to have precluded the use of falsetto at any point in the range.41 Tosi is the first source to discuss this issue, though it is unclear whether his equation of voce di testa with falsetto extends to all voice types.42 We can only surmise how smoothly blended was the transition between registers before the end of the seventeenth century. It was certainly of the utmost importance to Tosi, who preferred head voice for executing passaggi and other ornaments. A blended register transition still did not mean that the Italians preferred a unified color to the voice; composers exploited the contrasts between the top and bottom. Like pop singers today, Italian Baroque singers were adept at switching between different registers, laying the foundation for the cantar di sbalzo techniques so essential for singers in the eighteenth century.

The predominance of speech mode that characterized the stile rappresentativo began to reach its limitations with the need for more sound and the development of a more lyrical aria style; it continued, of course, as the technique for recitative. Recitative style evolved into a more rapid, parlando character, though vestiges of the older stile rappresentativo can be heard in Antonio Cesti's Orontea (1656), for example, alongside the newer arioso and parlando styles. Troat articulation also continued into the eighteenth century. There is no reason to think that the flexible airstream so characteristic of Italian Baroque vocal technique would have changed, either, as the qualitative aspect of the words did not lose its importance altogether. Singers added to these resources a more cantabile style of singing, capable of a wide variety of colors and dramatic characterizations. If their breath technique and laryngeal position were not fundamentally changed in order to execute the glottal action of throat articulation and to project the qualitative aspect of the Italian language, then this style of singing would have involved increased use of subtle adjustments of the vocal tract itself to achieve greater intensity of sound and more variety of sound qualities.

This cantabile style continued to allow singers extremely fine pitch control. Any increase in sonority would not have been so great as to lead to pitch distortion or to constant pitch-fluctuation vibrato. While singers then and now might agree that it is important to sing in tune, the definition of what is “in tune” has changed considerably. For those of us raised in a predominantly equal-tempered sound world, unequal temperaments can be a revelation. Modern computer technology and tuning boxes now make it possible to access exactly all sorts of different tuning systems with precision. Of chief importance for singers is not only developing the ear to match the pitches of the continuo and obbligato instruments, but also recognizing the implications of accurate pitch and temperament for how one sings and how one responds to the music. Temperament itself has expressive dimensions.43

Chromaticism was also an important expressive device, used by many Italian composers. In the seventeenth century, the major and minor semitone, such as D# and ![]() , were distinctly different pitches, as Maugars indicates in describing the singing of Leonora Baroni: “When she passes from one note to another she sometimes makes you feel the divisions between the enharmonic and the chromatic modes with such artistry that there is no one who is not greatly pleased by this beautiful and diffcult method of singing.”44

, were distinctly different pitches, as Maugars indicates in describing the singing of Leonora Baroni: “When she passes from one note to another she sometimes makes you feel the divisions between the enharmonic and the chromatic modes with such artistry that there is no one who is not greatly pleased by this beautiful and diffcult method of singing.”44

The distinction between the major and minor semitone has strong implications for the amplitude of pitch-fluctuation vibrato.45 In order to preserve the distinction between the major and minor semitone, the total amplitude of pitch-fluctuation could not have exceeded a quartertone-substantially smaller than what we hear today. In comparison to modern operatic singing, this involves a completely different vocal aesthetic, a different technique, and a different way of conceiving of vocal sound altogether. One cannot sing this repertory successfully using a technique that requires suppression of vibrato in the vocal tract to “straighten” the sound, which may cause tension and fatigue. In order to maintain pitch control, one must use much less air pressure than in modern operatic singing. Any “straightening” of the sound must be done at the point of imaging the sound before one sings, not after it has been initiated.

As opera developed, a singer's skill in acting became increasingly important. Maugars observed that Italian singers “are almost all actors by nature.”46 The anonymous author of the acting treatise Il corago (ca. 1630) reminds us that “above all, to be a good singing actor, one must also be a good speaking actor.”47

FRANCE

We are fortunate in having several detailed sources on French singing from the seventeenth century, the most important of which are Bénigne de Bacilly's Remarques curieuses sur l'art de bien chanter (1668) and Marin Mersenne's Harmonie universelle (1636).48

French singing did not undergo the radical changes seen in the Italian school at the turn of the seventeenth century,49 though the French were certainly aware of developments in Italy. Mersenne, for example, mentions Caccini, who performed at court in 1604/1605. There were notable champions of the Italian style of singing in France, as demonstrated by various efforts (ultimately unsuccessful) to establish Italian opera there. One of Louis XIII's favorite singers, Pierre de Nyert, the teacher of Bacilly and Michel Lambert, studied briefly in Rome, and a handful of castratos sang at the court of Louis XIV prior to 1700.50 Although Italianisms became increasingly present in French music toward the end of the century, in the main the style and technique of French singers differed considerably from those of their Italian counterparts.

Early seventeenth-century French singing retained many aspects of sixteenth-century technique, particularly with respect to breathing. I have described the French approach to breathing as a “steady-state” system, where air pressure, speed, and volume remain virtually constant.51 Such a system is perfectly suited to the quantitative nature of the seventeenth-century French language and to the chanson mesurée and air de cour. Troat articulation, known in France as disposition de la gorge or simply disposition, was also used in the elaborate doubles, ornamented second verses of airs, as well as for agréments.

Airs de cour were published in great numbers throughout the century and served as the model for the operatic airs of Jean-Baptiste Lully. They were often performed in the salons of the précieux, for an elite audience as preoccupied with the refinement of language as with dress and manners. Singers had to be as concerned with pronunciation as with any other aspect of their art. The French took the concept of Mundart very seriously.

Pronunciation meant more to the French than just the accurate delivery of the sounds of speech. It involved (1) proper execution of the sounds of the language without foreign accent; (2) clear delivery of those sounds so that the words could be understood in a room of any size; (3) the proper observance of syllabic quantity; and (4) inflection of the words in a way that facilitated perception of both their meaning and their underlying passion. French actors were highly skilled in these aspects of pronunciation. We know that Lully developed his style of recitative in part by hearing the declamation of the actress Marie La Champmeslé. Singing required a more heightened and exaggerated declamation than speech, one that conveyed both the character of the words and the passion they expressed. Perhaps it is the spirit of Cartesian rationalism that explains why French writers on singing-Mersenne and Bacilly in particular-codified and preserved the art of French singing diction in detail.

Any thorough investigation of French singing diction must confront the differences between the seventeenth-century and modern versions of the language, as well as the differences between the quantitative character of French at this time and other qualitative European languages. Because of its defining importance to French vocal style and technique, one can make a strong argument for using historical pronunciation in performances of seventeenth-century French vocal music. The details of pronunciation with respect to both vowels and consonants are available in the primary sources. Bacilly also discusses syllabic quantity in great detail.52 The most striking difference between seventeenth-century court pronunciation and modern French in terms of vowel sounds is the -oi vowel, which was pronounced oé or oué until the Revolution.53

Even before the publication of René Descartes's Passions de l'âme (1649), Mersenne (Descartes's schoolmate and correspondent) had observed, “each passion and affection has its proper accent.”54 Mersenne outlines three primary passions, each with varying degrees of intensity: anger, joy, and sadness. Anger, for example, is best conveyed by abruptly cutting off end syllables of words and by reinforcing final notes.

The projection of a particular passion was chiefly achieved by the degree of emphasis given to the consonants—either through duration or forcefulness of articulation. Bacilly outlines a technique of prolonging or suspending consonants, later called “consonant doubling” by Jean-Antoine Bérard.55 The Italians, by comparison, centered their expression in the vowels, which could bloom and color with the qualitative inflection of the words.56 If we regard Italian singing as “singing on the vowel,” then we can view French singing as “singing on the consonant.”57

Bacilly devotes a chapter to the technique of consonant inflection to express the passion of the words. Consonants that are to be prolonged can be sung (i.e., given pitch, in the case of voiced consonants) and sustained (for voiced consonants and fricatives) longer or shorter and articulated harder or softer, depending on the passion being expressed. The force of the consonant articulation would not alter the dynamic level of the subsequent vowel(s), which was governed by the steady-state airstream onto which the consonants were placed. The prolongation of the consonants would affect, however, both the duration of the subsequent vowel(s) and the relationship of the vowels and consonants with respect to the rhythm. Prolonged consonants can bleed over into the beat, rather than coming slightly ahead of the beat as is normally done in singing Italian. This technique, which is similar to some styles of pop singing today, should not be confused with the plosive, aspirated consonants associated with some schools of modern choral diction or with the German approach to consonants discussed below.58

Because consonants contain much greater expressive information in the French school, the interaction between singer and accompanist(s) is different. The accompanist must listen in a different way to coordinate with the consonants—both in time and character—more than with the vowels. The resulting articulation matches quite well with the style brisé of plucked instruments, which is perhaps why Bacilly preferred the theorbo for accompanying the voice.

The French found a way of compensating for most singers’ tendency to spend less time on consonants in singing than in speaking. They intuitively understood what we now know scientifically, that to reach a threshold of intelligibility, a brief acoustic event such as a consonant needs to be higher in amplitude or longer in time. They also understood the expressive parameters in amplitude and duration to convey meaning and feeling. With consonants voiced on a precise pitch, we can be virtually certain that subvocal “scooping” was not a general feature of French singing at this time.

Both Mersenne and Bacilly describe a quality of the ideal singing voice that is related to harmonie, a certain quality of body or focus in the sound that was independent of the overall size of the voice. Mersenne describes this quality as being like “a canal which is always full of water” as opposed to a “thin trickle,”59 while Bacilly describes it as the “amount of tone or harmonie present in the voice” that “nourishes the ear.”60

Because of the degree to which consonants were “sung” in the French school, proper pitch control was of great importance. Mersenne's comments on intonation and evenness make it clear that vibrato was an ornament in the French school. He indicates that there should be no fluctuation in pitch when sustaining a tone, even when there is a crescendo or decrescendo.61

By the early eighteenth century, we can document several types of ornamental vibrato used by the French. One type, produced in the throat, Michel Pignolet de Montéclair terms the tremblement feint, in which the beating was “almost imperceptible.”62 The faté was a breath vibrato appropriate for long notes, in which the amplitude was so small that it did not “raise or lower the pitch.” This is perhaps more akin to what we would regard as intensity vibrato today. Montéclair described a third type of vibrato: “The balancement which the Italians call tremolo produces the effect of the organ tremolo. To execute it well, it is necessary that the voice make several little aspirations more marked and slower than those of the faté.”63 Montéclair also describes a nonvibrato tone appropriate for long notes: “The son flé is executed on a note of long duration…without any vacillation at all. The voice should be, so to speak, smooth like ice, during the entire duration of the note.”64

Délicatesse was a quality highly prized by the French, especially in the execution of ornaments, as Mersenne indicated in describing the trill:

And if one wishes to do this trill with all its perfection, one must even more redouble the trill on the note marked with a fermata [d'un point dessus], with such a délicatesse that this redoubling is accompanied by an extraordinary lightening [adoucissment] that contains the greatest charms of the singing proposed.65

Mersenne is describing a kind of singing so delicate that the finest nuances of throat articulation could be executed. This is chamber singing at its most subtle. The visual analogue to the delicate filigree of French ornamentation style is the lacelike decoration of the silver furniture at Versailles (most of which was melted down to pay for Louis XIV's aggressive wars).66

Perhaps the most important characteristic in an ideal French singing voice was douceur, a quality of sweetness that Bacilly felt came naturally to a belle voix and that could be cultivated in others. Mersenne wrote,

But our singers imagine that the esclamationi and the accenti which the Italians use in singing smack too much of Tragedy or Comedy, which is why they don't want to do them, though they ought to imitate what is good and excellent in them, because it is easy to temper the esclamationi and to accommodate them to the douceur Françoise, in order to add what they have more of in the Pathetic to the beauty, clarity and sweetness of trills, which our musicians do with such good grace, when having a good voice they have learned the method of proper singing from good masters.67

There is no extended discussion of vocal registers in French sources until the late eighteenth century.68 One possible conclusion is that they used primarily only one register, at least for a given piece. The French, who favored equality over variety, clearly did not employ a vocal concept similar to the Italian “pyramid.”

The French did recognize the existence of natural and falsetto registers. Bacilly observed that natural-voiced singers scorned falsettists and that the falsetto voice tended to be more brilliant (éclatante), the natural voice, more in tune. Bacilly preferred small voices and high voices and generally felt that female voices (and falset-tists) were at an advantage over male voices, though not entirely. He writes, Bacilly distinguished different qualities of voices-pretty, good, light, big, expressive, brilliant-but viewed them as qualities in different singers, not incorporated in one voice. The French recognized the individual variety in the human voice and felt that not every singer was equally suited to every type of expression.

It is established that feminine voices would have the advantage over masculine ones were it not for the fact that the latter have more vigor and strength for executing runs and more talent for expressing the passions than the former. For the same reason, falsetto voices bring out much more clearly what they sing than natural voices. However, they are somewhat harsh and often lack intonation, so that instead of being well cultivated they seem to be faded [passé] in nature. In addition I cannot avoid mentioning in passing an error all too common in the world concerning certain falsetto voices…whether because one is set awry in spirit or perhaps because these sorts of voice are in some fashion against Nature, it is easy to scorn them and to speak ill of those who possess such voices. Although upon reflection one must observe that they owe everything in their vocal art to their voices thus elevated in falsetto, which renders certain ports de voix, certain intervals and other charms of singing quite differently than the tenor voice.69

Bacilly considered the following to be vocal faults: singing in the nose; poor voice projection; poor trills and accents; placing ornaments incorrectly, such as at the end of a song; executing runs with the tongue and with unevenness and rushing (avec certaine inégalité & précipitation); poor pronunciation; and confusing long and short syllables. Bacilly preferred to hear the musical talents of a singer rather than the vocal quality in and of itself.70

Both Mersenne and Bacilly identified four general voice types: basse (or bassetaille), taille, haute-contre, and dessus.71 Of these four, the haute-contre has been the least well understood and was for Lully perhaps the most important, for he wrote many title roles for this voice type, reflecting the French preference for higher voices of both sexes.72 It is generally accepted today that the French haute-contre was not a falsetto voice, but a very high natural one with a range from g to a', extending occasionally to b'.73

The French stressed the qualities of intonation, evenness, clarity, flexibility, sweetness, sonority, and body in the ideal singing voice. French singing was expressive in the small, highly nuanced details of text delivery-especially in the conso-nants―and ornamentation. There was a clear demarcation between principal notes and notes of ornamentation. This is a vocal aesthetic substantially different from that cultivated by modern singing methods.

GERMANY

German sources on singing from the seventeenth century outnumber both Italian and French. As the chart in Figure 1.1 indicates, there are strong links among the German sources. The model established by Michael Praetorius in Syntagma Musicum III (1619) was imitated throughout the century by writers who tried to convey what they understood of the Italian style of ornamented singing. Though there was increasing impact of Italian musical developments in Germany as the century progressed, the vocal aesthetic that emerges from German treatises changed relatively little, except in its attitude toward falsetto.

Praetorius called attention to the close connection between singing and oratory. It was important for a singer to have not only a good voice, but also an understanding and knowledge of music, skill in ornamentation (which required throat articulation), good diction, and proper pronunciation. We can establish from Praetorius that the Germans ca.1620, like the Italians ca. 1600, used throat articulation, prized the development of good breath control, and did not favor using falsetto. Praetorius's description of the requisites of a good singing voice has been quoted frequently, in modern times often as a defense for using continuous vibrato:74

The requisites are these: that a Singer first have a beautiful, lovely, agile [zittern] and vibrating [bebende] voice…and a smooth [glatten], round throat for diminutions; secondly, the ability to hold a continuous long breath without many inhalations; thirdly, in addition, a voice…which he can hold with a full and bright [hellem] sound without Falsetto (which is a half and forced voice).75

In the above quotation, Praetorius's term zittern probably signifies more than its literal meaning of “trembling.” Considered in light of Zacconi's discussion of the importance of the tremolo for learning the gorgia technique and singing passaggi (see above), it is likely that Praetorius (who learned much from Italian theorists) was referring not to continuous pitch-fluctuation vibrato, but to that “trembling” of the voice that is the essence of glottal technique, and hence the source of vocal agility. When considered in the context of the standards of intonation during this period, Praetorius's use of the word bebende could perhaps best be translated as “shimmering,” again conveying a voice using intensity vibrato rather than pitch-fluctuation vibrato. Though Johann Andreas Herbst would later quote this passage verbatim,76 it is perhaps not insignificant that forty-six years later (and sixty-nine years after Praetorius) Georg Falck, who also follows the passage closely, omits the words zittern and bebende altogether in his description of the ideal singing voice.77

Christoph Demantius outlined six important elements in proper singing in his influential Isagoge artis musicae (8th ed., 1632): (1) accurate pronunciation of vowels; (2) careful attention to semitones; (3) matching the tone of voice to the affect of the text; (4) correct intonation and proper awareness of the harmony; (5) avoidance of shouting; and (6) proper attention to the text and avoidance of breath articulation or “ha-ha-ha” in coloratura passages. Though he makes no direct reference to throat articulation, Demantius's admonition against breath articulation or aspiration is quite clear and was closely quoted by Falck.78 Demantius did not mention vibrato.

Christoph Bernhard outlined nine elements of good singing, the first of which he called fermo, which was keeping the voice steady on all notes except when doing a trillo (single-note repercussion) or an ardire, an ornamental type of vibrato for passionate expression. In any other context, polished singers did not use pitch-fluctuation vibrato, which Bernhard termed tremolo, with the exception of basses, who used it seldom and only on short notes.79

Bernhard's student Wolfgang Mylius followed Praetorius's model in his Rudimenta Musices (1686), except that, in his description of the ideal singing voice, he omitted the word zittern and used belebende, meaning “lively,” where Praetorius had used bebende: “First a youth or singer must have by nature a beautiful, lovely, lively [belebende] voice well-disposed to a trill and a smooth, round throat.”80

Praetorius, Wolfgang Caspar Printz, and Falck all used the term zittern in connection with what we would call a trill today, but which they called tremolo.81 Mylius also used zittern to refer to the two-note trill, while Printz and Falck used it in conjunction with the single-note trillo.82 Zittern thus seems to refer to vocal agility, implying throat articulation, akin to the Italian term dispositione. Printz used the term Bebung to describe the trilletto, probably an intensity vibrato: “Trilletto is only a vibrating [Bebung] of the voice so much gentler than the trillo that it is almost not struck [with the throat].”83 Intensity vibrato or “shimmer” gives vitality to a tone while keeping the pitch steady. Printz's description of his trilletto seems to have been the basis for Martin Heinrich Fuhrmann's tremoletto, which he described in terms not unlike Printz's: “Tremoletto is a vibrating [Bebung] of the voice, almost not struck at all, and happens on one note or in one Clave, as is best to show on the violin, when one lets the finger remain on the string and as with the shake, slightly moves and makes the tone shimmer [schwebend] .” 84 Furhmann also gave a musical example, shown in Example 1.2. This further clarifies Praetorius's use of the term bebende. The evidence in the German sources clearly supports the use of intensity vibrato and strongly suggests very limited use of pitch-fluctuation vibrato as a fundamental aspect of the German vocal aesthetic throughout the seventeenth century.

EXAMPLE 1.2. “Tremoletto” from Martin Fuhrmann, Musicalischer Trichter, p. 66.

Printz provided a very detailed description of the lightness and rapidity of throat articulation, which was the principal technique for executing ornaments. He recommended keeping the mouth in an average opening, the cheeks in a natural position (not raised, as in a “smile” position), the tongue relaxed, and the jaw still.85 Printz's comments should dispel any notion that a single-note trillo sounded like a bleating of a goat: “Troat articulation (the beating in the throat) happens very gently, so that the voice does not become fatigued [geschleisset] .” 86

In the second half of the century, the Germans seem to have followed an evolution similar to the Italian school, though a bit later, in mixing the falsetto with the natural voice. With the greater cultivation of different voice registers, the Germans also followed the Italians in applying the “pyramid” shape of the voice. Printz articulated this concept quite explicitly: “The more a voice ascends and the higher it is, the more subtle and softer it should sing, and the lower a voice gets, the greater the strength should be given to it.”87 The pyramid concept provides the dynamics that are not notated in the score.

The German vocal ideal then was one of a lovely, light, well-supported voice that accorded itself to the meaning of the words, was agile, unforced, and “shimmering” (i.e., with intensity vibrato), using falsetto only when absolutely necessary at the top of the range and, in the second half of the century, following the “pyramid” shape of the Italian school.

Printz, like Bacilly and Mersenne, understood the need for greater clarity in singing consonants, especially in larger spaces. His solution was to make the consonants higher in amplitude (not longer in duration as discussed above for French singing), with a forceful, hard pronunciation:

The consonants should be very strongly pronounced, especially in large rooms or in open spaces. Vowels are easy to do on account of their sounds, but not consonants. So that one can understand the consonants from far away, they must be pronounced harder than in normal speech, yea almost excessively hard.88

The German language, like Italian, is qualitative. German writers recognized the dynamic ebb and flow of the language in good oratory and in good singing.89 It is likely, then, that German singers used a flexible breath stream similar to the Italians', whose style(s) and technique(s) of singing they so frequently emulated.

ENGLAND

We have few English sources on singing from the seventeenth century, though there is a considerable body of material on oratory, rhetoric, and acting.90 The evolution from the lute songs of John Dowland to the continuo songs of the Lawes family (Henry and William) to the late songs of Henry Purcell shows remarkable developments in both declamatory style and vocal technique. Part of this evolution, of course, involved a synthesis of an indigenous English style with Italian and, to a lesser extent, French influencess, in addition to the gradual development of professional singing.

The migration of Italian music and musicians to England in the early decades of the century involved the madrigal more than monody. Before about 1625, English solo singing largely perpetuated sixteenth-century practice.91 Only two court musicians arrived from Italy in the years between 1603 and 1618.92 A very few English musicians, notably Dowland, Nicholas Lanier, and possibly John Coprario, traveled to Italy. Robert Dowland published a lute-song version of Caccini's “Amarilli, mia bella” in 1610, and other versions of this song (some quite florid) were circulated in manuscripts, but relatively few Italian monodies were exported to England.

The English Renaissance style of singing is outlined in William Bathe's Briefe Introduction to the Skill of Song (ca. 1587). Bathe stressed the importance of (1) singing the vowels and consonants distinctly, according to local pronunciation; (2) having a breath technique to sing long phrases and a tongue capable of clear enunciation at a fast tempo; (3) a knowledge of musical notation and the proper proportion of note values; and (4) maintaining a clear voice for proper intonation.93

Lanier introduced the Italian stylo recitativo to England ca. 1613 in Tomas Campion's Squires’ Masque (1613). Lanier's Hero and Leander (ca. 1628) is a direct imitation of Claudio Monteverdi's recitative-lament style, though it is hampered a bit by the greater profusion of consonants and the different accentual patterns of the English language.

Charles Butler's Principles of Musick (1636) is one of the earliest seventeenth-century sources to discuss singing in detail. He called attention to the importance of the text as the element that sets singing apart: “Good voices alone, sounding onely the notes, are sufficient, by their Melodi and Harmoni, to delight the ear: but beeing furnished with soom laudable Ditti they becoom yet more excellent.”94

Butler further indicated that the punctuation of the text should provide the punctuation for the music. A singer's observation of textual and musical punctuation is important in shaping the rhetorical and dramatic structure of any vocal piece. Early seventeenth-century English composers often amplified the text through different rhetorical means of word repetition.95 Declaiming the text, both for diction and rhetorical emphasis, is extremely important in this repertory. Pronouncing the words distinctly was an important consideration for an English singer, particularly in an age in which the quality of the poetry often exceeded that of the music. Butler understood the importance of proper posture when singing and seems to describe the use of speech mode in advocating that singers sing “as plainly as they would speak”:

Concerning the Singers, their first care shcolde bee to sit with a decent erect posture of the Bodi, without all ridiculous and uncoomly gesticulations, of Hed, or Hands, or any other Parte: then ((that the Ditti (which is half the grace of the Song) may bee known and understood)) to sing as plainly as they woolde speak: pronouncing every Syllable and letter (specially the Vouels) distinctly and treatably. And in their great varieti of Tones, to keepe stil an equal Sound: (except in a Point) that one voice droun not an other.96

One possible interpretation of “equal” in the passage above is that the English in the first third of the century did not use “pyramid” registration (at least in a polyphonic context) and favored an equal balance of all the voices. However, this interpretation is possibly contradicted by Butler's observation, again in a polyphonic context, that “The Bass is so called, becaus it is the basis or foundation of the Song, unto which all other Parts bee set: and it is to be sung with a deepe, ful, and pleasing Voice…. The Treble…is to bee sung with a high cleere sweete voice.”97 Butler's concept of “equality” in this case might have meant equal within the parameters of the pyramid-a balance different from the modern norm.

Butler's description of the countertenor voice also is puzzling: “The Countertenor or Contratenor, is so called, becaus it answeret the Tenor; thowgh commonly in higher keyz: and therefore is fttest for a man of a sweete shril voice.”98 What Butler meant by “shril” is unclear; it may simply be an indication of falsetto. Edward Huws Jones has argued that the English countertenor voice is equivalent to the modern tenor, the English “tenor” to the modern baritone.99 René Jacobs regards the low Purcellian countertenor and the French haute-contre as having “very much in common .” 100 By the time of Purcell, the countertenor voice used both natural and falsetto registers.

John Playford's translation of Caccini's preface to Le nuove musiche (1602) was not published until the 1664 edition of A Breefe Introduction.101 Playford's glosses on Caccini are of considerable interest, particularly with respect to the trillo. Playford indicated that one can approximate the sound of the trillo by shaking the finger upon the throat, and also that it could be done by imitating the “breaking of a sound in the throat which men use when they lure their hawks.”102

Playford's “Directions for Singing after the Italian Manner” lasted through the twelfh edition of A Breefe Introduction (1694). It seems that the early Italian methods persisted in England until at least ca. 1680 and likely into the early1690s, considerably longer than in Italy. According to Ian Spink, the trillo had become obsolete in England by 1697.103

During the Restoration there was a resurgence of interest in Italian music. The king had his own group of Italian musicians, and castratos and other Italian performers arrived bringing the music of Giacomo Carissimi and Alessandro Stradella, among others, to the awareness of the English. The existence of Pietro Reggio's treatise The Art of Singing (1678) further suggests that in the last quarter of the century, the English used a fundamentally Italian singing technique, but it would have accommodated the English language and the mixed musical style of the period.104

Pronunciation of English changed considerably during the seventeenth century: Restoration English, for example, is even further removed from modern “BBC” English than seventeenth-century French is from its modern counterpart. There was significant interest in England in establishing a standardized orthography during this period, and as a result there are some very useful sources for historical pronunciation. Among the most detailed is Christopher Cooper's The English Teacher or the Discovery of the Art of Teaching and Learning the English Tongue (1687).105 Using Restoration pronunciation changes the vowel sonorities significantly from modern English and restores many rhymes that are now considered “eye rhymes.”

In comparison to Italian, seventeenth-century English was regarded as problematic for setting to music. Playford wrote:

The Author hereof [i.e., Caccini] having set most of his Examples and Graces to Italian words, it cannot be denyed, but the Italian language is more smooth and better vowell'd than the English by which it has the advantage in Musick, yet of late years our language is much refined, and so is our Musick to a more smooth and delightful way and manner of singing after this new method by Trills, Grups and Exclamations, and have been wed to our English Ayres, above this 40 years and Taught here in England; by our late Eminent Professors of Musick, Mr. Nicholas Laneare, Mr. Henry Lawes, Dr. Wilson and Dr. Coleman, and Mr. Walter Porter, who 30 years since published in Print Ayres of 3, 4, and 5 Voyces, with the Trills and other Graces to the same. And such as desire to be Taught to sing after this way, need not to seek after Italian or French masters, for our own Nation was never better furnished with able and skilful Artists in Musick, then it is at this time, though few of them have the Encouragement they deserve, nor must Musick expect it as yet, when all other Arts and Sciences are at so low an Ebb.106

Playford is referring to a quality of smoothness in singing the text, reflecting the Italianate “singing on the vowel.” Depending on the style in a late seventeenth-century English piece, I sometimes slant my text delivery to include aspects of both the Italian and French schools.

Vibrato was a vocal ornament in English singing as it was elsewhere in Europe.107

SPAIN

Spanish contributions to musical developments in Italy were significant: the Spanish may have given Italy the castrato voice.108 Many elements from Spanish spoken theater (such as buffo parts, the character of the servant-confident, and the mixture of different elements of social class) were incorporated into Italian opera. While these elements sparked many musical developments in Italy, they did not lead to the same degree of innovation in Spain, where the Baroque arrived much later than elsewhere in Europe. The court of Philip IV was conservative, the musical life of the chapel heavily steeped in the Renaissance Flemish tradition. Foreign influencess on Spanish musical life in the second half of the century were also limited, though this was not for lack of exposure.109

The principal treatise we have for Spanish singing is Domenico Pietro Cerone's El melopeo, published in Naples in 1613 and written in Spanish (not Cerone's native language), possibly in order to curry favor with Philip III and the Spanish viceroy in Naples. A very conservative work, El melopeo nonetheless exerted a profound influence in Spain that lasted into the late eighteenth century. An enormous volume, it is the earliest music treatise still surviving that was brought to the New World.110

Book VIII of El melopeo deals with glosas, which we might call in English “running divisions,” and with garganta technique, the throat articulation technique that singers used to execute them. One can view this section as Cerone's diminution manual in the sixteenth-century tradition of Diego Ortiz, and of Tómas de Santa Maria, from whom Cerone borrowed some examples.

Cerone says little about vocal technique and claims that his aim is to aid the beginning glossador; yet he does tell us that cantar de garganta means the same thing as cantar de gorgia in Italian.111 The glosas require agility (destreza), lightness (ligereza), clarity (claridad), and time (tiempo). These descriptive words are strikingly similar to the words used by the French in outlining the ideal singing voice. Cerone makes it clear that the number of notes in a division do not need to add up metrically but that perfection consists more in maintaining the time and the measure than in running with lightness, because if one reaches the end too late or too soon, everything else is worthless. He also recommends, unlike the Italians, doing the division in one breath. Execution of divisions for Cerone requires primarily (1) strength of the chest (fuerça de pecho), by which I think he means breath capacity rather than strong air pressure-since he goes on to say he means by this being able to sing to the end of the line, and (2) the disposition of the throat.

Spanish singers used a fundamentally Renaissance vocal style and technique until very late in the seventeenth century. Many of the texts of later seventeenth-century tonos and tonadas are of a narrative or descriptive nature, not expressive in the manner of an Italian monody. Their general style is restrained and simple, though they may have been ornamented in the garganta style. Louise Stein has pointed out that most of the actress-singers active on the Spanish stage were not well educated and were trained by rote in a traditional, popular style,112 in marked contrast to the training of the Italian castratos.

One of the challenges in performing Spanish vocal music of this period lies in finding a balance between the accentuation of the text and the (often complex) musical rhythms. Sprezzatura does not seem to have been adopted by the Spanish. Although one might occasionally apply “corrective” word accentuation, the overriding rhythmic vitality of the music seems to take precedence as a general rule over accentual matters of the text. This creates a typically Spanish dynamism between the words and the music.

CONCLUSION

The pan-European approach that has characterized many performance-practice surveys dealing with singing and the widespread availability of recordings in our own time have led to a regrettable homogenization of performance styles in present-day performances of seventeenth-century music. As we have shown, significant differences existed among the various national schools of singing during the seventeenth century. There are also aspects of the singing of Jacopo Peri, Caterina Martinelli, Barbara Strozzi, Anna Renzi, John Pate, John Gosling, Antoine de Boesset, Michel Lambert―to name but a handful of great singers from the seventeenth century—that were probably as distinctive and unique to each of them as is the case in the singing of Placido Domingo, Renée Fleming, Barbra Streisand, Bobby McFerrin, and Andrea Bocelli today. In performing seventeenth-century vocal music (or any vocal music, for that matter), one must match technique and style not only to the time period, region, physical setting, genre, voice type, and range required, to the accompanying instrument(s), pitch standard, and tuning system being used, and to the particular piece of music at hand, but also to the unique characteristics of one's own voice and musical personality.

Exploring historical vocal techniques and the culture(s) in which they were developed connects us to the music more directly and enriches our understanding of it. It also makes it easier to sing!

NOTES

The first epigraph is from Dowland, Ornithoparcus: 88.

The second epigraph is from the translation in MacClintcock, Readings: 173.

1. For a comparison of these two schools, including audio examples, see Sanford, “Comparison.”

2. See Sanford, “Comparison”: paras. 1.1 and 1.2.

3. von Ramm, “Singing Early Music”: 14.

4. “Das erste bestehet in rechter Aussprache der Worte, die er singend fürbringen soll, dannenhero ein Sänger nicht schnarren, lispeln, oder sonst ein böse Ausrede haben, sondern sich einer zierlichen und untadelhaften Aussprache befleissen soll. Und zwar in seiner Muttersprache soll er die zierlichste Mund-Arth haben, so dass ein Teutscher nich Schwäbish, Pommerisch [etc.], sondern Meissnisch oder der Red-Arth zum nächsten rede, und ein Italiener nicht Bolognessich, Venedisch, Lombardisch, sondern Florentinisch oder Römisch spreche. Soll er aber anders als in seiner Muttersprache singen, so muss er dieselbe Sprache zum aller wenigsten so fertig und richtig lesen, alss diejenigen, welchen solche Sprache angebohren ist. Was die Lateinische Sprache anbelanget, weil dieselbige in unterschiedenen Ländern unterschiedlich ausgesprochen wird, so steht dem Sänger frey, dieselbe so, wie sie an dem Orthe, wo er singt, üblich ist, auszusprechen.” Bernhard, Von der Singe-Kunst, 36. Bernhard goes on to say that it is also prudent to pronounce Latin in an Italian manner.

5. For further information on historical pronunciations, see Copeman, Singing in Latin; Duffin, “National Pronunciations” and “Pronunciation Guides”; Sanford, “Guide.”

6. The first writer to identify the locus of this technique was Maffei, Discorso: 30. For a more physiological and scientific description of this technique, see Sherman/Brown, “Singing Passaggi.”

7. This is my empirical observation. Sherman/Brown did not address this issue.

8. Maugars, Response, trans. in MacClintock, Readings: 122.

9. See Sanford, “Comparison”: para. 2.2. Sherman/Brown, “Singing Passaggi”: 36n24, have observed: “Increasing the subglottal breath pressure has the following effects…it makes the execution of florid passages difficult or impossible.”

10. Zacconi, Prattica di musica: 58: “Questi tali che hanno tanta prontezza, & possanza di pronuntiar a tempo tanta quantità di figure con quella velocità pronuntiate: hanno fatto, & fanno si vaghe le cantilene; che chi hora non le canta come loro a gli ascoltavanti da poca sodisfattione, & poco da cantori vien stimato. Questo modo di cantare, & queste vaghezze dal Volgo communemente vien chiamata gorgia: la qual poi non è altro che un aggregato, & collettione di molte Chrome, & Semichrome sotto qual si voglia particella di tempo colligate: Et è di tal natura, che per la velocità in che si restringono tante figure; molto meglio si'impara con l'udito che con gli'essempii.” See also MacClintock, Readings: 69.

11. For more detailed discussion see Sanford, “Comparison”: par. 7.1 and audio examples 15, 16. See also Sanford, Vocal Style: 51ff; and Greenlee, “Dispositione”: 47-55.

12. “Cioè il cominciarsi dalla prima semiminima, e ribattere ciascuna nota con la gola.” Caccini, Nuove musiche: preface.

13. Strunk, Source Readings, Baroque: 25.

14. Zacconi, Prattica: 60: “che il tremolo, cioè la voce tremante è la vera porta d'intrar dentro a passaggi, & di impataonirse [sic] delle gorgie.” See also MacClintock, Readings: 73.

15. See, for example, Harris, “Voices”: 105.

16. Zacconi, Prattica: 60: “acilita mirabilmente i pincipii de passaggi.” See also MacClintock, Readings: 73

17. Gable, “Observations”: 94, suggests this. Intensity vibrato is produced with a different vocal mechanism than the trillo, so the former would not lead directly into the latter. See also Kurtzman, Monteverdi Vespers: 388-389.

18. If, for example, one chooses to use throat articulation for passaggi with note values transcribed as modern sixteenth notes, a normative tempo range would be from![]() 104/106 at the slower end to

104/106 at the slower end to![]() 122/124 at the faster. For audio examples using throat articulation, see my recordings of Purcell's “Hark, the echoing air” on the CD From Rosy Bowers, Albany Records Troy #127 (1994), which at around

122/124 at the faster. For audio examples using throat articulation, see my recordings of Purcell's “Hark, the echoing air” on the CD From Rosy Bowers, Albany Records Troy #127 (1994), which at around![]() 108 is one of the fastest recorded tempos for this piece to date, and the final Presto (V) movement of Antonio Bononcini's “Laudate Pueri” on the CD Antonio and Giovanni Bononcini: Sonatas and Cantatas, Centaur CRC 2630 (2003), which is at a tempo of

108 is one of the fastest recorded tempos for this piece to date, and the final Presto (V) movement of Antonio Bononcini's “Laudate Pueri” on the CD Antonio and Giovanni Bononcini: Sonatas and Cantatas, Centaur CRC 2630 (2003), which is at a tempo of![]() 122. Both of these audio examples are available on iTunes.

122. Both of these audio examples are available on iTunes.

19. See Sanford, “Comparison”: paras. 2.2, 2.6, and audio examples 4, 8.

20. See New Grove Dictionary of Opera: s.v. “Stile rappresentativo.”

21. “Bisogna avvertire di osservare i piedi de i versi, cioé di trattenersi nelle sillabe lunghe, e sfuggir nelle brevi, perche altrimeni si faranno de barbarismi.” See also Sanders, “Vocal Ornaments”: 70-71.

22. “Ma dalle voce finta non può nascere nobilità di buon canto: che nascer à da una voce naturale comoda per tuta le corde.” Strunk, Source Readings, Baroque: 31-32. Praetorius also reiterated Caccini's point of view. See below.

23. “E perche trattano o d'Amore, or di sdegno che tiene l'Amante con la cosa amata, si rappresentano sotto Chiave di Tenore, cui intervalli sono propri, e natural del parlar mascolino, parendo pure al Autor sudetto cosa da ridere che un huomo con voce Feminina si metta a dir le sue ragioni, e dimandar pietà in Falsetto ala sua innamorata.”

24. See Kurtzman, Vespers: ch. 15.

25. Viadana remarks in the preface to Concerti ecclesiastici (1605), for example, “Che in questi Concerti saranno miglior effetto i Falsetti, che i Soprani naturali, si perche per lo piu Putti cantano trascuramente, e con poca gratia come anco perche si è atteso alla Lontananza, per tender piu vaghezza, no vi è peró dubbio, che non si puo pagare condenari un buon Soprano naturale: ma se netrovano pochi.” (“In these concertos, falsettos will have a better effect than natural sopranos; because boys, for the most part, sing carelessly, and with little grace, likewise because we have reckoned on distance to give greater charm; there is, however, no doubt that no money can pay a good natural soprano; but there are few of them.”) Trans. in Strunk, Source Readings, Baroque: 62.

26. For a discussion of the voce mezzana, see Jacobs, “Controversy”: 289.

27. See Gerbert, Scriptores: 3: 120. See also Herlinger, Lucidarium: 540 (14.1.11 and 14.1.15) and 542 (14.1.18).

28. [When chant is sung by two or more singers,] “Tertium est, ut voces dissimiles in tali cantu no misceant, cum non naturaliter, sed vulgariter loquendo, quedam voces sint pectoris, quedam gutturis, quedam vero sint ipsius capitis.” Coussemaker, Scriptorum: 1:93b.

29. Zacconi, Prattica: 77r.

30. Sanders, “Vocal Ornaments”: 73.

31. “…whoever wishes to sing well and clearly must employ his voice in three ways: resonantly and trumpet-like for low notes, moderately in the middle range and more delicately for the high notes, the more so the higher the chant ascends.” Trans. in Conrad/Dyer, “Singing”: 217. See also Jacobs, “Controversy”: 289.

32. MacClintock, Readings: 62.

33. Celletti, Bel Canto: 16.

34. MacClintock, Readings: 189.

35. See Rosand, Opera: esp. ch. 8.

36. Celletti, Bel Canto: 19.

37. Rosand, Opera: 24.

38. The Sistine Chapel had begun replacing falsettists with castratos in the late sixteenth century. See Kurtzman, Vespers: ch. 15.

39. For more detailed discussion of the castrato voice, see Heriot, Castrati; New Grove, s.v. “Castrato”; Haböck, Kastraten; Sawkins, “For and against.”

40. Celletti, Bel Canto: 39. Burney recounts that the castrato Matteo Berselli, who was active in the 1720s, could go from c' to f'” with “the greatest of ease.” Quantz gives Farinelli's range as from a to d'” in 1726, adding several notes a few years later. See Sanford, Vocal Style: 23.

41. I use my falsetto for special effects. Many popular female singers do, as well.

42. See Tosi, Opinioni: 37ff. See also Julianne Baird's remarks concerning Tosi in the following chapter. Many writers after Tosi equated head voice and falsetto.

43. For a general introduction to temperaments, see Neuwirth, Musical Temperaments. See also Myers, “Tuning and Temperament,” in this volume and Duffin, “Tuning and Temperament,” in the Renaissance volume of this series.

44. MacClintock, Readings: 122.

45. See Moens-Haenen, Vibrato.

46. MacClintock, Readings: 122.

47. Trans. in Termini, “Baroque Acting”: 149. For more information on singers’ acting and movement in the seventeenth century, see Brooke A. Bryant, The Seventeenth-Century Singer's Body: An Instrument of Action. PhD dissertation, City University of New York, 2009.

48. Other sources include Jean Millet (1666), Jean Rousseau (1683), François Raguenet (1702), and Jean-Laurent Le Cerf de la Viéville (1704).

49. Anthony (French Baroque: 45) has discussed the musical conservatism of France in the seventeenth century.

50. See Sawkins, “For and Against.”

51. See Sanford, “Comparison”: para..2.5.

52. See also Ranum, Harmonic Orator.

53. For a discussion and examples of seventeenth-century French pronunciation, see Sanford, “Comparison”: pars. 5.1, 6.1-6.4 and audio examples 5, 13, 16. See also Sanford, “Guide,” and Gérold, L'Art: 215ff.

54. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle: 2:367.

55. Bacilly, Remarques: 307ff.

56. To hear examples of this Italian approach, see Sanford, “Comparison”: audio examples 4, 6, 8, 15.

57. Ibid.: audio examples 5, 9, 13, 16.

58. Ibid.: audio examples 5, 13, 14.

59. “Il y a encore une autre qualité de la voix qui la rend plaine, & solide, & qui augmente son harmonie, ce que l'on peut expliquer par la comparaison d'un canal qui est toujours plain d'eau, quand elle coule, ou par celle d'un corps, & d'un visage charnu & en bon point; au lieu que les voix qui sont privées de cette qualité, sont semblables å un filet d'eau qui coule par un gros canal, & à un visage maigre, & decharné.” Mersenne, Harmonie universelle: 2:354. See also Sanford, Vocal Style: 5f.

60. “Il y a encore une Remarque à faire dans la difference des Voix, par le plus ou le moins de son & d'harmonie qu'elle produisent, c'est à dire qu'il en est qui remplissent, ou pour parler dans les termes de l'Art, qui nourissent mieux l'oreille que d'autres plus deliées, & que dans le langage ordinaire on nomme des Filets de Voix, bien qu'elles se fassent entendre d'aussi loin, qu'elles ayent autant ou plus d'étendue que les premieres.” Bacilly, Remarques: 47. See also Sanford, Vocal Style: 6.

61. “La justesse consiste à prendre le tone proposé, sans qu'il soit permis d'aller plus haut, ou plus bas que la chorde, ou la note au'il faut toucher, & entonner. L'égalité est la tenue ferme, & stable de la voix sur une mesme chorde, sans qu'il soit permis de la varier en la haussant ou en la baissant, mais on peut l'affoiblir, & l'augmenter tandis que l'on demeure sur une mesme chorde.” Mersenne, Harmonie universelle: 2:353.

62. “On appuye d'abord le Tremblement feint, comme si l'on avoit dessein de former un Tremblement parfait, mais aulieu de battre longtems, on ne donne après cet appuy, et å l'extremité de la note, qu'un petit coup de Gosier dont le battement est presqu'imperceptible.” Montéclair, Principes: 83.

63. “Le Balancement que les Italiens appellent Tremolo produit l'effet du tremblant de l'Orgue. Pour le bien executer, il faut que la voix fasse plusieurs petittes aspirations plus marquées et plus lentes que celles du Flaté.” Ibid.: 85.

64. “Le son file s'execute sure une note de longue durée, en continuant la voix sans qu'elle vacille aucunement. Le voix doit être, pour ainsy dire, unie comme une glace, pendant toutte le durée de la note.” Ibid.: 88. See also Sanford, Vocal Style: 231.

65. “Et si l'on veut faire cette cadence avec toute sa perfection, il faut encore redoubler la cadence sur la note marquée d'un point desssur, avec une telle delicatesse, que ce redoublement soit accompagné d'un adoucissement extraordinaire, qui cõtienne les plus grands charmes du Chant proposé.” Mersenne, Harmonie universelle: 2:355.

66. For examples of this silver furniture, see: http://www.boutiquesdemusees.fr/en/shop/products/details/815-exhibition-catalogue-when-versailles-was-furnished-in-silver.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IomiAXYcsOs

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yhmlqzhJeSc&feature=related

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x4ydzi_versailles-retrouve_school

http://www.apollo-magazine.com/reviews/473256/enthroned-in-silver.thtml

67. “Mais nos Chantres s'imaginent que les exclamations ![]() les accents dont les Italiens usent en Chantant, tiennent trop de la Tragedie, ou de la Comedie, c'est pourquoy ils ne veulent pas les faire, quoy qu'ils deussent imiter ce qu'ils ont de bon

les accents dont les Italiens usent en Chantant, tiennent trop de la Tragedie, ou de la Comedie, c'est pourquoy ils ne veulent pas les faire, quoy qu'ils deussent imiter ce qu'ils ont de bon ![]() d'excellent, car il est aisé de tem-perer les exclamations

d'excellent, car il est aisé de tem-perer les exclamations ![]() de les accommoder à la douceur Françoise, afn d'ajoûter ce qu'ils ont de plus pathetique à la beauté, à la netteté,

de les accommoder à la douceur Françoise, afn d'ajoûter ce qu'ils ont de plus pathetique à la beauté, à la netteté, ![]() à l'adoucissement des cadences, que nos Musiciens font avec bonne grace, lors qu'ayant une bonne voix ils ont appris la methode de bien chanter des bons Maistres.” Mersenne, Harmonie universelle: 2:357.