![]()

Trombone

In the beginning of the seventeenth century, the trombone consolidated the gains it had made over the course of the previous century. By this time the cornett had generally replaced the shawm in the standard wind ensemble, thus making it more flexible and more suitable for indoor as well as outdoor events. The trombone is a true “switch-hitter”: fully capable of playing loud, outdoor music, when blown more discreetly it also blends nicely with voices and violins, as well as cornetts. This more subtle side of the trombone's personality also made it quite amenable to use in church.

The instrument also embarked on new endeavors. In 1597 Giovanni Gabrieli published in Venice the first compositions to specify trombones (along with other instruments)—the famous Sonata pian’ e forte and two canzonas. During the next thirty years or so, reams of music with parts for trombones, both instrumental and concerted vocal works, rolled off Italian presses. And quite early in the new century, the trombone began to participate in the newly developed practice of basso continuo, sometimes doubling the printed continuo part exactly, at other times simplifying it, and occasionally embellishing it.

The instrument was known by the name “sackbut” (and its cognates) in England and sacqueboute in France throughout the seventeenth century, but it has always been called trombone in Italy and Posaune or trombone (the latter especially in musical scores) in Germany. With the advent of the early-music movement in the mid-twentieth century, the term sackbut was adopted to refer to “reproductions” of early trombones, as a convenient way of distinguishing them from their modern counterparts.

THE INSTRUMENT

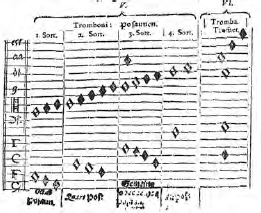

Michael Praetorius describes four sizes of the instrument:1

1. Alto (Alto oder discant Posaun [see Figure 7.1, no. 4]). Praetorius does not specifically state the pitch of the alto trombone, but the customary pitch must have been D. Its range was B to d” or e” (see Figure 7.2). Praetorius remarks that because of its small size, the sound of the alto trombone is inferior to that of the tenor; and moreover the latter, with practice, can be played as high as the alto.

Figure 7.1. Michael Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum II, Theatrum instrumentorum (1620), plate 8.

2. Tenor (Gemeine rechte Posaun [Figure 7.1, no. 3]). The tenor was pitched in A, although “first position” apparently was not generally played with the slidefully closed. Near the end of De Organographia (the main text of Syntagma II),2 Praetorius recommends using a trombone—particularly one made in Nuremberg—with its slide extended by the width of two fingers (zwei Querfinger) as the best source for an a in “choir pitch” (Chormasse, or north German Chorthon).3 A Nuremberg trombone was considered to be so consistent in pitch that it could serve as a pitch standard, yet the two-finger extension was required to allow for necessary adjustments of tuning.4

Plate VIII at the end of Syntagma II in the Theatrum instrumentorum (Figure 7.1) shows extra lengths of tubing, one straight and one coiled, that when fitted to the tenor trombone probably could lower the pitch of the instrument by a half step and whole step, respectively. The natural range of the instrument is identified in the text as E to f', but the table on page 20 of De Organographia lists g' to a' for the top (see Figure 7.2). The table also shows extension of this range from A1 to g”. Factitional tones (false or “bendable” notes), mentioned by Praetorius for the Octav-Posaun (see point 4 below), and/or pedal tones must have been used to obtain the lowest notes.

3. Bass (Quart-Posaun or Quint-Posaun [see Figure 7.1, nos. 15 and 2]). These two terms literally mean “fourth-trombone” and “fifth-trombone,” referring to the interval each sounds below the tenor—that is, E and D. Praetorius and others, however, often used the term Quart-Posaun in a generic sense to refer to any bass trombone, regardless of its specific pitch. The illustrations in Theatrum instrumentorum show two so-called Quart-Posaunen, varying slightly in size and configuration. Each instrument is fitted with a pushrod attached to a tuning slide, which probably was capable of lowering the pitch of the instrument by atleast a half step. Herbert Myers notes that each instrument is also fitted with a whole-tone crook.6 Thus instrument no. 2 in Figure 7.1, set up as depicted here, is technically a Quint-Posaun. But instrument no. 1 in Figure 7.1 is larger than no. 2, and to this issue we shall return shortly. Both of the bass trombones shown in Figure 7.1 have handles attached to the moveable slide-stay, without which it would be impossible to reach the lowest positions.

Praetorius gives the range of the Quart-Posaun as A1 or G1 to c' (extendable downward to F1 and upward to g')—thus he probably actually has the Quint-Posaun in mind here. He says that a tenor player can easily learn to play the Quint-Posaun by reading bass-clef parts as if they were in tenor clef.

Figure 7.2. Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum II, De Organographia (1619), p. 20.

4. Double-bass—Octav-Posaun. This instrument, rarely used, plays an octave below the tenor, and its normal range is E1 to a. The extended range is from C1 to c', but C1 and D1 are described as “falset” (i.e., factitious) notes which can be obtained with practice. Praetorius mentions two forms of the instrument: one is twice as long as the tenor in all dimensions,7 whereas the other, not physically as large, achieves its low pitch by means of crooks and a larger bore. Myers suggests that this second type of Octav-Posaun may be represented in Figure 7.1, no. 1, which Praetorius identifies as a Quart-Posaun and other scholars have assumed to be a Quint-Posaun, since it is clearly larger than instrument no. 2. The woodcuts in Theatrum instrumentorum were drawn to scale, with rulers (in Brunswick feet and inches) across the bottom of some of the plates. Myers carefully measured each drawing in plate VIII and discovered that even without its crook in place, instrument no. 1—which also appears to have a wider bore than no. 2—stands not a fourth or a fifth, but a major sixth below the tenor. With the whole-tone crook in place and the tuning slide extended, the instrument would thus be an octave below the tenor.8

Figure 7.3. Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum II, Theatrum instrumentorum, plate 6 (detail).

An illustration in Marin Mersenne's Harmonie universelle (1636) shows a tenor trombone with a double coil of tubing inserted between the slide and bell sections, which, he tells us, lowers the pitch of the instrument by a fourth, converting it into a Quart-Posaun.9 He further states that the instrument can be disassembled at several points, which are indicated by some of the letters in the diagram. The instrument therefore had friction joints rather than solder joints.

Figure 7.4. Marin Mersenne, Harmonie universelle, vol. 3, p. 271.

In seventeenth-century sources one occasionally finds referencesto the Sekund-Posaun and/or Terz-Posaun, instruments apparently tuned a whole step and a third below the tenor in A. These terms must refer to tenor trombones with one or two additional coils of tubing inserted between slide section and bell section, as we have seen in Praetorius's plate VIII (Figure 7.1, no. 3). A painting by Lodovico Carracci (II paradiso, ca. 1616) shows what must be a Sekund-Posaun.10

Figure 7.5. Lodovico Carracci, Il paradiso (ca. 1616). Bologna, Church of San Paolo (detail).

By the latter part of the century, the soprano trombone had appeared, though only one such instrument survives.11 No published music from the period has parts written specifically for it.

The tenor was by far the most common size of the instrument during this period. There are a few references to bass trombones in Italian sources from the early part of the century, but in general, neither the alto nor the bass was used widely outside the German-speaking orbit. Significantly, the lone surviving Oktav-Posaun was made by a Nuremberg-born craftsman, Georg Nicolaus Öller, who immigrated to Stockholm.

Seventy-six trombones made in the seventeenth century still survive, including forty tenors, seventeen basses, seventeen altos, one soprano, and one contrabass. More than two-thirds of these were manufactured in Nuremberg; all of them were made in German-speaking regions or by makers who were native to those regions. Surviving basses are mostly from the early part of the century, while altos do not appear in significant numbers until the middle of the century.

Choosing an Instrument

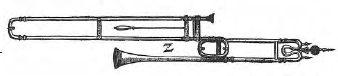

The market for reproductions of historical trombones is small and only a handful of makers build them today. Many of the “reproductions” made in the 1960s and 1970s were essentially just narrow-bore trombones with small bells, manufactured with little regard to historical specifications or methods of construction. In recent years, more faithful copies have become easier to find.

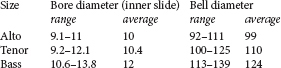

Historically, trombones varied in dimension to some extent, just as they do today. The following tables give the range of dimensions for bore and bell, with an approximate average for each.

Tenor bells tend to increase in diameter at the end of the century, particularly in the work of the Nuremberg maker Johann Carl Kodisch, but bore size, while variable, does not show a similar trend. The average thickness of the metal in the bell section is approximately .3 mm.

Early trombones were not lacquered, nor did they have slide stockings or water keys, though many reproduction instruments have them. It is unlikely that their presence has a noticeable effect on tone quality, but the prospective purchaser of an instrument should weigh the advantages and disadvantages and make a choice based on his or her needs. Virtually all surviving antique bass trombones have tuning slides, but tenors and altos do not. The principal purpose of the tuning slide on the early bass trombone was to alter the basic pitch of the instrument rather than to make small adjustments in tuning, but it is difficult to believe that early performers never thought of using them for the latter purpose. Again, the presence or absence of this device probably makes very little difference in tone quality, although their presence makes necessary a rather long cylindrical section within a section that is conical on the originals.12

Table 7.1. Dimensions (in millimeters) of Extant Seventeenth-Century Trombones

Some trombonists interested in playing early music but reluctant to spend the money required to purchase a high-quality reproduction instrument have resorted to cutting down the bell of a small-bore trombone. If the bell of the modern instrument has significant terminal flare, cutting off the last inch or so probably will not have a profound effect on pitch.

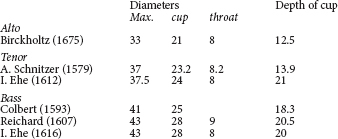

Choosing a Mouthpiece

Only a very few antique trombone mouthpieces survive. Their most salient characteristics are a broad, relatively flat rim, a bowl-shaped cup with a sharp-edged throat, and no back-bore. As some makers of early trombones do not supply mouthpieces with their instruments, it may be necessary to have a mouthpiece custom made. Dimensions for historical mouthpieces are given in Fischer (p. 52), Smith (p. 32), and Baines (p. 115). Baines's measurements of five surviving mouthpieces appear in Table 7.2.

A good instrument is expensive, but the money will virtually be wasted if a modern mouthpiece is used, since it will be very difficult to obtain the proper sound. David Smith argues that the trombone and its modern counterpart represent rather different acoustical systems, and therefore a mouthpiece designed to operate with one system is incompatible with the other.13 A modern trombone player, when converting to the early trombone, will frequently be reluctant to use a historical mouthpiece. The response will prove to be quite different, the tone quality may be airy at first, and the mouthpiece may simply not “feel right.” It takes some time to adjust to an unfamiliar mouthpiece.

PLAYING TECHNIQUE

Modern players of the trombone understand the instrument to have seven positions, disposed chromatically. In the seventeenth century, however, the tenor trombone was considered to have four diatonic positions, called “draws” (Zugen), corresponding approximately to modern first, third, fifth, and sixth positions. The earliest known illustration of these draws appears in Aurelio Virgiliano's Il Dolcimelo (ca. 1590). Praetorius describes the first draw as played, not with the slide fully closed, but pulled out by the width of two fingers (zwei Querfinger, or two fingers placed parallel to one another—approximately one and one-half inches). At least this is how he derives the a used as a tuning standard for organs in north German choir pitch (Chormass or ChorThon), which he mentions near the end of De Organographia (see endnote 2). He does not discuss the four draws in detail, but he marks them on the slide in the illustration of one of his bass trombones (see Figure 7.1, no. 2 above). Daniel Speer says that the first draw is by the mouthpiece (though he does not mention the “floating” first position discussed by Praetorius); the second, next to the bell; the third, four fingers beyond the bell; the fourth, as far as the arm can reach. He further notes that sharps are played by adjusting the slide upward from the main draw by the width of two fingers; the flats, by moving downward by the same distance. The alto trombone and Quint-Posaun, according to Speer, have only three draws, a major second apart.14

Table 7.2. Dimensions of Early Trombone Mouthpieces (in millimeters)

We have seen that early tenor trombones were built in A, altos in D, basses in E or D. Modern reproductions of tenors, however, are typically made in ![]() at a' = 440 Hz, with altos usually in

at a' = 440 Hz, with altos usually in ![]() and basses in F or

and basses in F or ![]() . In the seventeenth century, pitch standards varied considerably from one region to another, but in north Germany and Italy, throughout this period and well into the eighteenth century, trombones typically had to conform to ChorThon, a pitch standard that was approximately one-half step above modern pitch, or a'= 460/465 Hz. Coincidentally, this means that the seventeenth-century player's a was roughly the same pitch as a modern player's

. In the seventeenth century, pitch standards varied considerably from one region to another, but in north Germany and Italy, throughout this period and well into the eighteenth century, trombones typically had to conform to ChorThon, a pitch standard that was approximately one-half step above modern pitch, or a'= 460/465 Hz. Coincidentally, this means that the seventeenth-century player's a was roughly the same pitch as a modern player's ![]()

Many seventeenth-century composers who wrote for the trombone understood the instrument's tonal characteristics quite well, and this is reflected in the tonalities or modalities of their compositions. For example, Giovanni Martino Cesare wrote his La Hieronyma for solo tenor trombone and continuo (1621; see below under Repertory) in the Aeolian mode on A (i.e., A minor, from a modern perspective), which fits very nicely on an instrument in that key. The anonymous Czech sonata (ca. 1660; see below under Repertory), for trombone and continuo, is in D. Biagio Marini's Sonata for four trombones (1626) is in D, as is Johann Hentzschel's Canzon (1649) for eight trombones, and Johann Georg Braun's Canzonato (1658) for four trombones. Daniel Speer's Sonata for four trombones (1685) is in D and his two sonatas for three trombones (1697) are in A and E, respectively. Thus these composers seem to have had in mind the most suitable keys for trombones. It is perhaps worth noting that for a tenor trombone in A, the low ![]() is playable only in the fourth draw extended (without recourse to crooks) and hence difficult to execute in fast passages. Significantly, composers of this era tended to avoid this note when writing music intended exclusively for trombones. By way of comparison, we may note that near the end of the eighteenth century, when the basic pitch of the tenor trombone was considered to be

is playable only in the fourth draw extended (without recourse to crooks) and hence difficult to execute in fast passages. Significantly, composers of this era tended to avoid this note when writing music intended exclusively for trombones. By way of comparison, we may note that near the end of the eighteenth century, when the basic pitch of the tenor trombone was considered to be ![]() , Wolfgang A. Mozart wrote the trombone solo in the Tuba mirum of his Requiem in the key of

, Wolfgang A. Mozart wrote the trombone solo in the Tuba mirum of his Requiem in the key of ![]() major.

major.

Figure 7.6. Hans Burgkmair and others, Der Triumphzug Maximilians I (1526), plate 78 (detail).

Some surviving historical trombones built before 1630 have tubular slide-stays, but in most cases these are probably later replacements. Some trombones built after 1630 also have flat stays, but tubular stays, which were often telescoping, became more common after that date. Players of the modern trombone often find it uncomfortable to hold a replica trombone with flat stays, as grasping it in the modern way is awkward at best. The right hand, wrapped around the moveable slide-stay, is relatively comfortable, but the left hand, with the left thumb hooked onto the bell-stay and fingers wrapped around the immoveable slide-stay, is not. One of the principal problems—apart from the sharp edges of the flat slide-stays and bell-stay—is that the bell-stay is positioned too far from the immoveable slide-stay for the left hand to wrap around both comfortably. The early grip was not standardized, but Keith Mc-Gowan, in an article in Early Music, demonstrates a more appropriate and comfortable manner of holding the instrument, based on early iconography—in particular, the illustrations of trombonists from the set of woodcuts known as The Triumph of Maximilian I (Hans Burgkmair and others, 1526).15 In this grip, the player makes no attempt to grasp the bell-stay and instead wraps the index and middle fingers around the mouthpipe, with the ring and little fingers underneath the immoveable slide-stay, the thumb wrapping around that same stay. The right hand holds the moveable slide-stay underhanded (see Figure 7.6). Early pictures of trombonists vary considerably, but many show the player holding the instrument rotated approximately ninety degrees clockwise (from the player's perspective) from the customary modern position. In this position, then, the slide-stays are roughly parallel to the ground, the bell-stay, perpendicular to it.

Embouchure

Embouchure development is a difficult and time-consuming process, and for this reason, conversion of musicians with little or no previous experience on a brass instrument requires a great deal of patience. The mouthpiece typically should be placed equidistant laterally between the corners of the mouth, with more of the mouthpiece on the upper lip than on the lower. It is important to keep the corners of the mouth firm while playing. For help in embouchure development, the novice trombone player is encouraged to seek the assistance of a teacher of modern trombone.

ARTICULATION AND ORNAMENTATION

Articulation for wind instruments is described in several sources from the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. One of the most comprehensive of these is Girolamo Dalla Casa's Il vero modo di diminuir (1584); Francesco Rognoni-Taeggio (Selva di varii passaggi, 1620) describes very similar articulations. Both treatises illustrate various types of “double-tonguing” for the cornett, primarily for playing diminutions. Bruce Dickey summarizes these articulation practices in his chapter on the cornett in this volume. Dickey says that there are “three kinds of double tonguings: (1) te che te che, (2) te re te re, and (3) le re le re. The first of these tonguings was described as hard and sharp, the third as smooth and pleasing, the second as intermediate.”16 As Dickey notes, Giovanni Maria Artusi in 1600 states that unlike the cornett, the trombone had only one tonguing. It is difficult to believe, however, that early trombonists did not resort to double-tonguing in fast passages, particularly when playing with cornettists who were double-tonguing. Perhaps we can forgive Artusi for his remarks about the trombone, however, for the rapid divisions found in trombone parts in such works as Francesco Rognoni-Taeggio's Susanne ung jour and the sonatas of Dario Castello (see below under Repertory), which would be almost impossible to execute without double-tonguing, were written two decades and more after Artusi's treatise appeared. Praetorius mentions two virtuosos capable of playing in the extreme ranges of the tenor instrument, Phileno of Munich (i.e., Phileno Cornazzini, also a cornettist) and Erhardum Borossum of Dresden. The latter musician, according to Praetorius, could play the tenor trombone as high as a cornett and as low as a bass trombone, with leaps and ornaments in the manner of a viola da bastarda or cornett.

The trills indicated for trombones in Castello's sonatas were probably intended as repeated-note ornaments, in the manner described in Giulio Caccini's Le Nuove musiche (1602). In music composed during the latter part of the century, the tr sign should usually be interpreted as an alternating-note trill, executed with the lip. Speer states that trombonists should perform trills with the chin, which amounts to the same thing.

Occasionally the trombonist was expected to play a tremolo, though the meaning of this term fluctuated in the early seventeenth century. In a passage in long notes from Biagio Marini's La Fosacarina: Sonata à 3 con il tremolo, for two violins (or cornetts), trombone, and continuo, the trombonist is instructed to “tremble with the instrument” (tremolo col strumento), the violins, simultaneously, to “tremble with the bow” (tremolo con l'arco). Exactly what Marini means here is clarified by an instruction in the organ part: “set the tremolo” (metti il tremolo). Thus the organist is to activate the tremulant stop, creating a gentle and affective pulsating of the sound, produced by varying the pressure in the wind chest. The violins, playing half notes, are to imitate the organ tremulant by varying the pressure of the bow on the string, within a single bow stroke, while the trombone creates undulations with the breath. This effect is not frequently required in trombone parts, though it is occasionally indicated later in the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth—sometimes in more descriptive notation, with repeated eighth notes connected by slurs, and sometimes with staccato dots accompanying the slurs.

REPERTORY

As mentioned above, trombones were used extensively in church music in the early seventeenth century, doubling or replacing voices, joining the continuo, or providing a completely independent voice. When playing with voices, trombonists often performed parts not specifically designated for any instrument, either replacing a voice or doubling it. They could play the middle and lower parts of generic instrumental music—particularly dance music, such as that in Johann Hermann Schein's Banchetto musicale (1630). But as noted above, beginning in 1597 with Giovanni Gabrieli's collection Sacræ symphoniæ, parts were frequently written specifically for them, in both concerted vocal and purely instrumental works. Bruce Dickey's chapter “Cornett and Sackbut” in this guide identifies some of the many collections of instrumental music for which the cornett-and-trombone ensemble, typically in five or more parts, is suitable, though usually not specified.

So much music was written for trombones in the seventeenth century that it is impossible to list more than a representative sampling here. The homogeneous trombone ensemble was not particularly common, yet a few such works written specifically for such an ensemble survive. They include:

For three trombones and continuo:

Daniel Speer, two Sonatas (1697) (Musica Rara)

For four trombones and continuo:

Johann Georg Franz Braun, Canzonato (1658) (Max Hieber)

Giovanni Martino Cesare, La Bavara (1621) (Musica Rara)

Biagio Marini, Canzona (1626) (Ensemble Publications)

Daniel Speer, Sonata (1685) (Ensemble Publications)

For five trombones and continuo:

Moritz von Hessen, Pavan (Ensemble Publications)

For eight trombones and continuo:

Tiburtio Massaino, Canzona (1608) (Musica Rara)

Johann Hentzschel, Canzon (1649) (R. Ebner)

For trombone solo:

Giovanni Martino Cesare, La Hieronyma (1621) (Max Hieber)

Francesco Rognoni Taeggio/Orlando di Lasso, Susanne ung jour (1620)

Anonymous (Czech), Sonata for Trombono solo and Basso (late 1600s)

(Ensemble Publications)

Of these solo works, the first and third have continuo parts. The second, Francesco Rognoni Taeggio's setting for Violone Over Trombone alla Bastarda of Orlando di Lasso's four-part chanson Susanne ung jour, is quite interesting. The “bastard” style referred to here involves the instrumentalist jumping from one part to another, ornamenting copiously, while a chordal instrument—most likely a keyboard—plays the preexisting chanson. Bastarda settings were more commonly written for string instruments, and it is significant that in Rognoni's setting the trombone serves as an alternative for the violone. Conversely, in Cesare's La Hieronyma (which is not a bastarda setting) the trombone is mentioned before the viola. The interchangeability of the trombone with a low-pitched string instrument thus parallels the cornett's relationship to the violin.

Another “bastard” setting with trombone is P. A. Mariani's Canzon à 2 alla Bas-tarda Per il Trombone, e Violino Per il Deo Gratias (1622; see below under Repertory). As with the work by Rognoni, the trombone player's progress through the various ranges is indicated by means of clef changes. The title of the work indicates that it was intended for church performance, as a substitute for the Deo Gratias at the end of the Mass.

There are further possibilities for solo music for trombone. The ranges of the four solo canzonas for bass instrument by Girolamo Frescobaldi are perhaps more suitable for the bass trombone than the tenor, though with the use of factitional tones they can be played on the latter instrument. And Frescobaldi's five canzonas for solo treble instrument and continuo work well on a tenor trombone, with the solo part transposed down an octave. This practice has some historical justification, as tenor singers often treated solo vocal works written for soprano in the same way.

Also worthy of note for performers are several sacred works with solo voices, for which trombones provide the only accompaniment apart from the continuo. Jerome Roche calls these works “trombone motets.”17 Among many such works, I cite the following (all with basso continuo or basso seguente):

Giovanni Gabrieli, Suscipe clementissime (1615), for six voices and six trombones (Gabrieli, Opera omnia, vol. 4).

Ludovico da Viadana, O bone Jesu (1602), for tenor voice and two trombones (Edition Walhall).

Amante Franzoni, Sonata sopra Sancta Maria (1613), for soprano voice and four trombones.18

Ercola Porta, Corda Deo dabimus (1620), for soprano and alto voices and three trombones.

Giovanni Martino Cesare, Beata Virgo Maria (1621), for tenor voice and three trombones.

Heinrich Schütz, Fili mi Absalon (1629), for bass voice and four trombones (Bärenreiter).

Schütz, Attendite, popule meus (1629), for bass voice and four trombones (Bärenreiter).

Andreas Hammerschmidt, Gott mir sei gnädig (1642), bass voice and two trombones (Parow'sche Musikalien).

Johann Rudolf Ahle, Herr, nun läßt Du deinen Diener (1658), for bass voice and four trombones (Parow'sche Musikalien).

Ahle, Höre Gott (1665), for five voices and seven trombones (A-R Editions, Recent Researches in the Music of the Baroque Era, vol. 131).

The two works by Schütz are some of the most satisfying works ever written for trombones.

Music for Trombone in Small Mixed Ensembles

Particularly in Italy, the trombone sometimes appeared in small ensembles with violins and/or cornetts. Some rather virtuosic writing for the trombone can be found in the works of the enigmatic Venetian composer Dario Castello. Sonata quinta from his 1621 collection is written for treble instrument, trombone (or violetta), and continuo. The trombone part is every bit as active as the treble part (probably intended for violin or cornett), engaging in fast-paced dialogues with the higher instrument. In the middle of the composition both instruments have rather extended, florid solo passages, improvisatory in style. The sonatas for two violins, trombone, and continuo by Antonio Bertali are similar in format to Castello's, with elaborate but brief solo passages for all three concertizing instruments. Bertali's trombone parts appear to have been composed with the tenor trombone in mind, though both sonatas published by Musica Rara require an occasional low D, which on a tenor must be played as a factitious tone. Selected works in this category include:

Giovanni Paolo Cima, Sonata (1610) for cornett and trombone, or violin and violone.

Giovanni Picchi, two Sonatas for violin, trombone, and continuo; two Sonatas for two violins and trombone (1625) (Studio per Edizioni Scelte [facs. ed.]).

Biagio Marini, La Foscarina (1617), for two violins or cornetts, trombone, and continuo (Ars Antiqua).

P. A. Mariani, La Guaralda (1622), for violin, trombone, and continuo, “per il Deo Gratias.”

Antonio Bertali (1605–69), two Sonatas for two violins, trombone, and continuo (Musica Rara).

John Hingeston (1606–83), Fantasia for cornett and trombone (Musica Rara).

Dario Castello, five Sonatas for one treble instrument and trombone, two Sonatas for two treble instruments and trombone, two Sonatas for two treble instruments and two trombones, one Sonata for two violins and trombone (2 books, 1621 and 1629) (Studio per Edizioni Scelte [facs. ed.]; some edited in Recent Researches in the Music of the Baroque Era, vols. 23 and 24).

Bartolomeo Mont'Albano, two Sinfonias for two violins and trombone (1629).

Adam Jarzebski, one Concerto (i.e., canzona) for soprano instrument and “bastarda” or trombone; one Concerto for bassoon and trombone (1627) (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne).

There are so many large vocal works with parts for trombones from the seventeenth century that it is pointless to list even a representative sampling here.

The seventeenth century eventually took its toll on the trombone. By the 1630s the instrument had entered a decline, which was particularly profound in Italy. Perhaps the plagues that ravaged the peninsula at this time had something to do with this; and farther north, the Thirty Years’ War certainly had a negative effect. By the end of the century, the trombone had become marginalized in Italy, France, England, Spain, and the Low Countries, though it continued in frequent use in the German-speaking orbit, particularly in church and civic music, in both Catholic and Protestant regions.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Howard Weiner in preparing this article.

NOTES

1. Praetorius, Syntagma II: esp. 20, 31–32, and plates VI and VIII; Praetorius/Crookes—Syntagma II: 20, 43–44.

2. Praetorius, Syntagma II: 232.

3. See Myers, “Praetorius’ Pitch”: 29–45; see also Myers, Chapter 20, “Pitch and Transposition” in this volume.

4. The two-finger extension may also have been necessary because of the position of the left hand; see McGowan, “The World”: 441–466, esp. 449.

5. Concerning the identification of the size of the trombone marked no. 1 in Figure 7.1, see below, under “Double-bass (Oktav-Posaun) .”

6. See Myers, “Praetorius’ Pitch”: 38.

7. Refer to Will Kimball's website (http://www.kimballtrombone.com/trombone-history-timeline/17th-century-first-half/) at the following entry: “1620, Germany: Also included, on a separate plate of Praetorius's Sciagraphia, is a highly-decorated bass trombone similar to an extant trombone by Johann Isaac Ehe (Nuremberg, 1612) (Praetorius II, plate 6; Naylor 196; public domain image).”

8. Ibid.

9. Refer to Will Kimball's website (http://www.kimballtrombone.com/trombone-history-timeline/17th-century-first-half/) at the following entry: “1636, France: Mersenne explains that in France, it is customary to create a bass trombone by simply adding a crook or tortil to the tenor trombone, lowering the pitch by a fourth (Bate 136).”

10. Refer to Will Kimball's website (http://www.kimballtrombone.com/trombone-history-timeline/17th-century-first-half/) at the following entry: “1616, Bologna, Italy: Ludovico Carracci's Paradise, an altarpiece painting located in the Church of San Paolo Maggiore, features an angel-trombonist situated prominently among a group of angel-musicians (see facing detail and full image below; public domain) (Komma, [Karl Michael. Musikgeschichte in Bildern. Stuttgart (1961):] 109; Emiliana, [Andrea. Le storie di Romolo e Remo di Ludovico, Agostino e Annibale Carracci in Palazzo Magnani a Bologna. Bologna, (1989):] 167).” For a color detail see also Bruce Dickey's online article “Why did the cornetto die out?” at http://www.concertopalatino.com/Decline_of_Cornetto.html.

11. An instrument by Christian Kofahl (Grabow, 1677), now in the Musikinstrumentenmuseum Schloss Kremsegg, Kremsmünster, Austria. For more on the soprano trombone, see Howard Weiner, “The Soprano Trombone Hoax,” Historic Brass Society Journal 13 (2001): 138–160.

12. I am grateful to Howard Weiner for this observation (personal communication, June 2010).

13. D. Smith, Trombone: 12–34.

14. Speer, Grundrichtiger: 222–223.

15. See McGowan, “The World”: 441–466, esp. 447–451.

16. Dickey, “Cornett and Sackbut,” in this volume.

17. Roche, North Italian: 82.

18. The soprano solo is quite similar to Monteverdi's work of the same name, though the instrumental parts are not.