![]()

Percussion Instruments and Their Usage

The seventeenth century marks a curious period in the history of percussion instruments. On the one hand, the usage and performance techniques of most percussion instruments apparently remained quite stable during these years. By contrast, the kettledrums or timpani, virulently condemned by Sebastian Virdung in 1511 as “the ruination of all sweet melodies and of all music,”1 were transformed from strictly outdoor, military instruments into an important component of concerted-music ensembles, particularly in sacred music. Because of these disparate evolutions, we will consider the performance practices and musical styles associated with percussion instruments outside the kettledrum family only in general terms,2 concentrating on the developments in musical style that shaped the literature and performance practices of the timpani.

PERCUSSION

Seventeenth-century sources generally corroborate Benjamin Harms's assertion that the construction and performance practices of most percussion instruments have changed relatively little in the centuries since the instruments’ first appearance.3 Two of the most important seventeenth-century authors who discuss instruments outside the kettledrum family are French (Marin Mersenne, 1636, and Pierre Trichet, ca. 16404), yet where percussion instruments and techniques are concerned, these writers concur to a remarkable extent not only with previous treatises, but also with their German contemporary Michael Praetorius.5 Indeed, the most important differences lie in the authors’ views on the merits of individual instruments. The French authors devote considerable space to a variety of percussion instruments, whereas Praetorius states that there is no need to discuss what he considers the “ragamuffin instruments” (lumpen-instrumenta)—including cymbals, cowbells, strawfiddles, hand cymbals, handbells, tambourines, field drums, anvils, and various Turkish instruments—because they “do not really belong in music.”6

This situation necessitates three important observations about perceptions and usages of the non-kettledrum percussion instruments in the seventeenth century. First, most verbal descriptions inevitably reflect French practices and tastes; concerning German opinions we have only Praetorius's dismissal and the fortunately detailed (and, for the time, remarkably ethnomusicological) illustrations provided in the Theatrum instrumentorum at the end of his De Organographia (1619; see Figs. 9.1 and 9.2). Second, the fact that Praetorius's lumpen-instrumenta, with the exception of strawfiddles, were all traditionally used in military music suggests that the rhythms used in playing these instruments might well have reflected the performance traditions of military music, which Praetorius and other theorists clearly do not consider true music. Finally, the late seventeenth century seems to have witnessed the emergence of somewhat distinct national drumming styles in military music, and this development would have influenced percussion instrumentation employed in any given piece on a specific occasion.7

Frame Drums: Hand Drum and Tambourine

These instruments, generally consisting of a cylindrical frame with a skin stretched across one end or (more seldom) both, are discussed by Trichet and illustrated by Mersenne and Praetorius.8 Information on the construction of the hand drums is limited to the explanation that the shell was usually made of wood and covered with some sort of skin; occasionally a snare was stretched across the bottom skin of the two-headed hand drum. These drums might be between two and five inches deep and six and fourteen inches across.9

Mersenne describes the tambourine as the tabour de Bisquaye and states that it consists of pairs of jingles (thin plates of metal or white iron) suspended on leather strings spanning slots cut into the shell; Trichet associates it with the Basques and their neighbors the Béarnois, and describes it as being about twelve inches across, shaped like a sieve or sifter.10

Hand drums and tambourines alike were played with the hand, not sticks or beaters. Hand drums probably made use of the same variety of techniques still employed today, using different parts of the hand and different types of finger strokes. Mersenne states only that the tambourine is played with the fingers; Trichet specifies that it is held in the left hand and played with agile movements of the fingers of the right hand.11

Figure 9.1. Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum II, Theatrum instrumentorum, plate 23; field timpani (1); field drums (2); Swiss fipple flute (3); anvil (4).

Though contemporary sources provide no clear indication of the musical contexts in which hand drums and tambourines were used, one might assume that both were employed in dance music (especially since there have evidently been no fundamental changes in performance technique such as those that might result from use of the instrument in a different stylistic context).

Figure 9.2. Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum II, Theatrum instrumentorum, plate 29: satyr pipes (1 and 2); American horn or trumpet (3); a ring, played by the Americans in the way we [Germans] play the triangle (4); American shawm (5); cymbals, upon which the Americans play in the way we play bells (6); a ring with jingles, which they throw into the air and catch again (7); American drums (8 and 9).

Two-Headed Cylindrical Drums:

Field Drum and Tabor

The principal differences between these drums and the hand drums were their dimensions, the manner in which they were struck, and their functions. In addition, there evidently was a substantial difference in function between the field drum and the tabor, though the construction was similar.

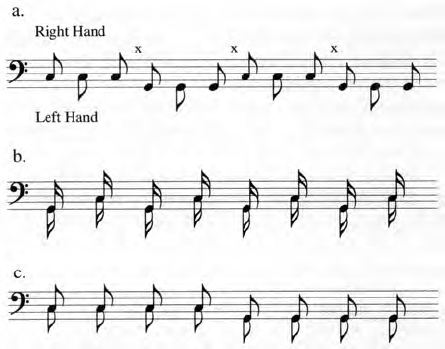

The most detailed description of the field drum is provided by Trichet, who states that it was normally used by the French in warfare as elsewhere and could be as much as two feet long and almost as wide. Each end was to be covered with a strong hide that was fastened near the rim by means of hoops, which in turn were bound to the hoops at the other end of the shell by means of cords. One head was to be spanned by a double string (snare), which preferably was made of gut, and the other head struck by two sticks, the size of which varied according to the dimensions of the drum.12 Mersenne illustrates two varieties of field drum. In the first, the tension on the rim of each head is adjusted by means of a counterhoop, whose suspension is controlled by tightening or loosening a node located on one side of the shell; a similar node on the other side of the shell was used to adjust the other head. The relatively precise tuning facilitated by this mechanism led Mersenne to discuss the use of field drums (not just timpani) in choirs of four or more, and to use this pitch differentiation in his sample rhythms for the drum (see Example 9.1).13

Mersenne's second variety of field drum (evidently corresponding to that discussed by Trichet) provides for no such flexibility in tuning the heads; they are attached directly to one another. Mersenne associates this drum with a pair of cymbals almost identical to modern ones and leaves no doubt as to his lack of respect for the two instruments, stating that the greatest pleasure they afforded consisted in the interest they held for artists and scientists.14

Example 9.1. Marin Mersenne, Harmonie universelle, drum rhythms.

The tabor was generally used along with a pipe, the two instruments played by a single person. It was suspended from the elbow, forearm, or wrist of one person and played with a single stick; the other hand was used on the three fingerholes of a fipple flute. Sebastian Virdung stated in 1511 that this combination was common among the French and the Dutch; Trichet stated only that it was common among the French.15

Since Mersenne and Trichet prescribed that the dimensions of cylindrical drums corresponded to the sticks used, and since the tabor was played with only one stick, the tabor itself probably tended to be smaller than field drums.

Other Nonpitched Percussion Instruments:

Cymbals, Triangles, Castanets, and Clappers

Mersenne's derogatory reference to cymbals marks the only appearance of plate-like cymbals in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writings on percussion.16 By contrast, the seventeenth-century preference seems to have been for small, handheld cymbals, each shaped like a small bowl. To judge from the illustrations provided by Praetorius and Mersenne, the diameter of these cymbals was not much greater than the span of the hand—perhaps six to eight inches.17

Mersenne stated that triangles were held suspended in the left hand and struck with a beater held in the right; they could be made of silver, brass, and all other metals, but ordinarily steel was used because of its “more piercing, merry, and exciting sound.” Around the bottom edge should be suspended a series of circular rings made of the same metal as the triangle itself.18

Mersenne and Trichet also mention castanets and clappers—groups of two or three pieces of metal or wood joined at one end and free to clap against one another at the ends. Both authors were impressed by the rapid diminutions possible on these instruments, stating that this effect “defied the imagination.”19 Trichet associated the castanets specifically with the Spanish, and Mersenne implied this association by stating that they were frequently used with the guitar; one might assume that they could also be used outside the context of music in the Spanish style, but no direct evidence to this effect seems to have survived.

Strawfiddle and Bells

The brittle tone of the strawfiddle or Strohfiedel (a xylophone with a single row of wooden bars resting on a wooden frame and supported by a bed of straw to keep the frame from damping the vibrations altogether) is aptly testified to by the instrument's appearance in Hans Holbein's terrifying sixteenth-century woodcut series Bilder des Todes (1532/1538).20 Apparently, however, Holbein's feelings were not universally held in the seventeenth century: Praetorius illustrated a similar instrument with fifteen graduated bars, and Mersenne stated that it provided as much pleasure as any other musical instrument, illustrating and discussing a Flemish variety consisting of seventeen bars, the highest of which was tuned a seventeenth higher than the lowest. Mersenne also reports that the longest bars were about ten inches long and suggests that they should be made of a “resonant wood such as beech” (though any number of other materials could be used, including other woods as well as brass, silver, and stones).21

But for Mersenne, bells were the most excellent of all percussion instruments: to them are devoted fully forty-seven of the sixty pages on percussion in the “Book on Instruments.” These bells, however, are not a series of graduated metal bars arranged according to pitch (the modern glockenspiel of orchestral bells), but traditional bells suspended with the open end down and struck by a clapper. In addition, the Italians G. B. Ariosti and G. Trioli wrote compositions for the sistro or timbale musicale, a glockenspiel with twelve bars played with wooden hammers.

The Sources

The fundamental change in the role of the kettledrums in seventeenth-century musical life is reflected in their greater prominence in contemporary writings about music. In the sixteenth century and earlier, information concerning the instruments and their use in contemporary music was transmitted primarily through iconographic sources and passing remarks in contemporary accounts of festivals, processions, and the like. But the seventeenth century produced at least five substantial discussions of the drums in writings about music. These writings, together with iconographic evidence and the relatively few surviving specimens of seventeenth-century instruments, provide a clear and exciting view of the performance practices and literature of the drums during their crucial period of transition.

The implication of this improved source situation can be fully appreciated only against the backdrop of the role the drums played in earlier times. In general, the timpani had been ignored in treatises on music; the earliest substantial discussion was Sebastian Virdung's 1511 diatribe in Musica getutscht. Referring to the “tympanum of St. Jerome” discussed in the so-called Dardanus letter often cited in contemporary discussions of sacred music,22 Virdung goes on to describe his contemporary timpani:

Of this instrument [the tympanum of St. Jerome] I know absolutely nothing, for the thing one now calls “tympanum”—the large field kettledrum—is made of a copper kettle and covered with calfskin, and is struck with sticks in such a way that it thunders very loudly and brightly.…These drums…cause much unrest for the honorable, pious elders, for the infirm and the ailing, and for the worshippers in the monasteries who must read, study, and pray; and I believe and hold it for truth that the devil conceived and invented them, for there is nothing holy or even good about them; instead, they are the ruination and the oppression of all sweet melodies and of all music. Thus, I can be absolutely certain that this “tympanum” that was used in worshipping God must have been a completely different thing than the drums we use now, and that we are completely wrong to give the name to that devilish instrument which is actually not worthy to be used in music…For if beating or rattling is to be music, then so must binders or coopers or those who make barrels also be musicians…23

The vehemence of Virdung's diatribe suggests that he was arguing against a practice that was gaining (or had already gained) some acceptance, as does the fact that he included the instruments at all. This impression seems to be corroborated by Michael Praetorius a century later. In volume II of Syntagma Musicum (1619), the Wolfenbüttel Kapellmeister condemns the timpani in language strikingly similar to Virdung's discussion, but in volume III (published the same year) he suggests the drums’ use, in the company of the trumpets, as a defining characteristic of the first of thirteen styles of arranging chorales and hymn tunes for polychoral ensembles. That Praetorius had so completely reversed his ideas on polychoral scoring techniques—an issue central to early seventeenth-century musical style—within the space of a year seems unlikely; more probably, he was simply reluctant to contradict Virdung's authority directly in De Organographia—a volume obviously conceived as a successor to Musica getutscht.24

After Praetorius we encounter two important French discussions of the drums: the “Livre des instruments” of Marin Mersenne's Harmonie universelle (1636) and Pierre Trichet's Traité des instruments de musique (ca. 1640). These are followed at century's end by Daniel Speer's important discussion of the timpani in his Vierfaches musikalisches Kleeblatt (1697).25 In addition to providing information concerning the construction and design of the instruments and mallets themselves, these sources reveal much about the way the drums were viewed in the seventeenth century and the musical contexts in which they were employed.

Finally, the seventeenth century provided a crucial source of information not available for the study of the drums during early periods: a multitude of actual scores and parts specifically designating the use of the timpani. The earliest known such work—Heinrich Schütz's setting of Psalm 136, performed in Dresden on November 2, 1617—was followed closely by Michael Praetorius's polychoral setting of the Christmas hymn In dulci jubilo, published in his Polyhymnia caduceatrix et panegyrica (Wolfenbüttel, 1618).26 These works, both of which call for ad libitum realization of the timpani part, were followed in France at mid-century by a number of notated parts in the operas and ballets of Jean-Baptiste Lully. The 1680s witnessed the emergence of a number of notated parts in Austria—primarily Salzburg, where Andreas Hofer and Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber composed numerous sacred works employing the drums, including Biber's so-called “Festival Mass” (1682), which was long misattributed to Orazio Benevoli and erroneously cited as the work used for the dedication of the Salzburg Cathedral in 1628.27 In the closing decades of the century, notated timpani parts began to appear throughout Germany and Austria, thereby documenting the performance practices of the drum in the works of lesser-known composers such as Johann Philipp Krieger and Philipp Heinrich Erlebach, as well as those of Sebastian Knüpfer and Johann Schelle. These notated parts, some of which are replete with annotations from the timpanists who performed them, supplement the vast number of references to occasions at which the timpani and trumpets were employed ad libitum, and they provide a luxuriously detailed outline of the drums’ development.

Instruments and Mallets

Two commonly held misconceptions about the early timpani need to be corrected. First, the large kettledrums, with their screw-tightened heads and metal hemispherical kettles, are not (as is commonly believed) evolutionary descendants of the smaller nakers, whose heads were customarily lace-tightened and whose kettles, often as not, were made of wood or clay. Iconographic evidence clearly demonstrates that both varieties of drum—and a bewildering array of curious admixtures of their respective features—coexisted in both the East and West as far back as the thirteenth century. Moreover, small neck-laced kettledrums continued to be produced in what is now Western Europe up to the late nineteenth century—indicating, presumably, that they were still used in some musical contexts during that period. In other words, the timpani did not actually replace their supposed forebears; they merely occupied a more prominent position in the music that has been the subject of musicological and organological discussion (viz., orchestral music as opposed to, for example, dance-ensemble music).

More important for specific application in performance practice is the matter of the mallets used during the seventeenth century. Conventional wisdom has long held that the early timpani were played with wooden sticks and that the idea for covered mallets was developed by Hector Berlioz—an assumption clearly reflected in numerous “original-instrument” recordings that reveal an unreasonably harsh timpani timbre. The assumption that the use of softer covered mallets was Berlioz's innovation may stem from Berlioz himself; like many of the composer's eminently quotable anecdotes, however, it is ultimately untenable.28

In fact, most seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writings concerned with the performance of concerted music discuss uncovered wooden sticks as the exception rather than the rule. Daniel Speer, for example, states that the heads of the mallets were “wrapped in the shape of a small wheel,” and an anonymous author writing in Johann Adam Hiller's Wöchenliche Nachrichten und Anmerkungen die Musik betreffend in 1768 makes a similar remark, without indicating that the sound produced by such sticks was muffled rather than “usual.”29 The head of the mallet, according to these and other writers, could be either bead- or disc-shaped, but in most cases it was covered with leather, cloth, or wool. These possibilities seem to be corroborated by numerous illustrations that clearly suggest covered rather than unwrapped mal-lets.30 Thus the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century depictions of uncovered mallets in outdoor performance situations may well say more about the drums’ use in those contexts than in the performance of concerted music.

Three aspects of the drums’ construction merit discussion here. First, the modern timpanist uses heads of uniform texture and thickness, usually made from machine-honed aborted calfskin or (more commonly in the past twenty years) Mylar or polyethylene terephthalate; the eighteenth-century timpanist, however, generally had to work with thicker, hand-scraped heads made from some variety of animal skin. Calfskin was probably the most common material for the heads (it is cited by both Virdung and Praetorius31), but other materials were used, as well: Mersenne suggests sheepskin and advises against using muleskin, and the anonymous article in the 1768 Nachrichten und Anmerkungen states that muleskin and goatskin were also used.32 Some sources (Speer and Johann Philipp Eisel among them) suggest that the half-tanned heads were to be smeared with brandy or garlic and dried in the sun or at some distance from a small fire, but another anonymous eighteenth-century author quoted by Johann Ernst Altenburg in his Versuch einer Anleitung zur heroisch-musikalischen Trompeter- und Pauker-Kunst (Halle, 1770/1795) disagrees, suggesting that pure water could be used instead, without risk of corrosion.33 Obviously, for modern performers the latter is more practical—a means of maintaining the humidity and tension of the head similar to the way calfskin bass-drum heads are rubbed down with water to prepare them for use in concerts.

Second, though early timpani were generally smaller than their modern counterparts, the variation in size was considerable, even if one sets aside the smallest drums as belonging to the family of nakers rather than timpani. In general, the diameter of the modern drums used for the range of pitches normally encountered in the Baroque timpani literature, G to d, ranges from twenty-five to thirty-two inches (a modern twenty-five-inch drum will reach the pitch of f—virtually unheard-of in the Baroque literature). But Mersenne and Trichet speak of the largest early seventeenth-century French drums as about twenty-four inches in diameter, and the scale provided in Praetorius's Theatrum instrumentorum of Syntagma Musicum II suggests diameters of approximately seventeen and twenty-four inches.34 Even more interesting is that Mersenne, whose illustration reveals that his remarks concern neck-laced timpani apparently made of wood, prescribes that the pitch of the drums derived not so much from the tension on the heads as from the depths of the kettles.35 The timpani were to be employed in choirs of anywhere from three to eight drums, the kettles of which were to be scaled according to Pythagorean pitch ratios. Thus, if the largest drum available had a diameter of twenty-four inches, a drum tuned a fourth higher would be eighteen inches in diameter and a drum tuned an octave higher would be twelve inches in diameter. This prescription reflects the continuation of an old tradition of using timpani choirs—a transition that was first suggested in illustrations by Leonardo da Vinci and later developed into the use of multiple timpani in works by Johann Philipp Krieger, Christoph Graupner, Antonio Salieri, Antoine Reicha, and, of course, Felix Mendelssohn and Hector Berlioz.36

One final physical feature of the Baroque timpani merits description here: a device known as the Schalltrichter (lit., sound-bell), which was intended to increase the resonance of the drums. Similar in shape to the bell of a modern horn, the Schalltrichter was loosely mounted on the bottom inside of the kettle, extending upward into the interior of the drum from a small central hole at the bottom of the kettle. Surviving specimens clearly indicate that timpani continued to be made with the Schalltrichter well into the nineteenth century, but since the device was first mentioned by Eisel (who stated in 1738 that it was “currently in vogue”37), its use in the seventeenth century must remain a matter of conjecture. As we shall see, however, other aspects of early Baroque performance practice suggest that such a Trichter would have been useful already in the early seventeenth century.

Beating Spot

Equally profound differences were produced by one aspect of the Baroque timpanist's technique that has largely eluded scholarly attention: the different beating spot. The modern timpanist, whose drums for the Baroque repertory range from twenty-five to thirty-two inches in diameter, typically strikes the head about one-fourth the distance from the edge to the center of the drum. This technique emphasizes the harmonically related modes of vibration and effects a relatively long decay time, thus providing maximum resonance and a rich harmonic spectrum for the nominal pitch. There is also one disadvantage, however: the fundamental is almost completely absent. The nominal, or perceived, pitch sounds one octave above the fundamental, with accompanying partials a fifth, an octave, and a tenth higher; in effect, then, the fundamental is suppressed by its longer-lasting and harmonically richer overtones.38

In contrast to modern practice, all available evidence indicates that the Baroque timpani were struck exactly in the center of the head or within a centimeter or two of the center—the only location at which the audible pitch is the fundamental. This beating spot produced a sound substantially different from that for which modern timpanists strive: the decay was virtually immediate, and the pitch was deprived of the clarifying effect provided by the upper partials.

The sound produced by beating in the center might seem extremely unmusical by modern standards. But when one considers that the timpani were first used only in outdoor military contexts (where the open air would render negligible any lengthier decay time produced by striking closer to the edge), and that the Schalltrichter was apparently introduced not long after it had become common to use the drums indoors (where a longer decay time and greater clarity of pitch would have made an appreciable difference in the musical effect of the drums), the different beating spot seems logical.

Further evidence makes the argument even more convincing. For example, it would have been infinitely easier for a horse-mounted timpanist to strike the center of the smaller drums than to place his strokes as prescribed by modern practice. Moreover, early iconographic evidence, which usually is notoriously fraught with contradictions and inconsistencies, almost without exception clearly shows the drums being struck at the center of the head. And finally, the Schalltrichter makes no discernible difference in the tone or pitch of the drums if one strikes in the modern beating spot; if the beating spot falls in the center of the head, however, the device makes an appreciable difference in tone and pitch. In other words, the peculiar “sound-bell” popular in the early eighteenth century was evidently introduced to compensate for the thuddy tone produced by striking at the center of the head—and it both corroborates the early beating spot and indicates that greater resonance became desirable as the drums were increasingly used indoors, in concerted music.39

For the modern timpanist using Baroque-style drums, this means that the heads should be much tighter than they would be if one were to play in the usual modern beating spot. Tuning should be done by striking the head just off center in order to produce the nominal pitch in the same octave as if one struck a modern drum closer to the edge. The Schalltrichter will increase the resonance and clarity of the pitches, but the tone will still have a substantially shorter decay time than the modern norm. This quicker decay in turn facilitates what is probably the most far-reaching difference between Baroque and modern performance techniques: the liberal embellishment of the notated parts.

Embellishments

Though contemporary documents show that timpani were a regular component of concerted-music ensembles whenever a festive, courtly, or military context was to be suggested, most composers seldom wrote out timpani parts. In France, however, a tradition of notated timpani parts arose around mid-century (initially in the works of Jean-Baptiste Lully, and then in the works of his successors at the royal court). These parts, in keeping with general French notational trends, are extremely detailed. Evidently, the drums were provided with a notated part whenever their use was desired,40 and the specificity of the notation would have discouraged extensive ad libitum embellishment. Even the celebrated Marche pour deux timballiers (ca. 1685) by André Danican Philidor Sr. provides little room for embellishment, even though these pieces—surely designed as court entertainment—would have been a natural venue for virtuosic embellishment.

Outside France, a different practice seems to have obtained. If any single trait can be identified as common to almost all seventeenth-century timpani parts notated outside Lully's domain, it is that these parts comprise mostly “white notes” or other notes of relatively long rhythmic duration, rather than the typically busy figurations of the French parts, or those of the remainder of the ensemble in the more florid textures in which the timpani commonly are used. But since even modern drums are incapable of projecting the full duration of a note through the activity of an entire ensemble without using a roll, one must conclude that the Baroque timpanist was not expected to execute, for example, a notated whole note by simply striking the head and letting it ring. Instead, it was assumed that the timpanist would embellish the part as needed in order to maintain a sounding timpani presence throughout the duration of the notated rhythm.

Though there are exceptions to this general notational practice,41 general avoidance of detailed figures in Baroque timpani parts left the way in which the notated rhythms were embellished to the imagination of the timpanist. After all, guild-trained players—whose training centered around the art of embellishment—generally laid claim to all performance opportunities, sacred as well as secular, and no experienced guild player would have been inclined simply to strike the drums and let the dry, unadorned note die away with a simple thud. What follows is a summary of the various types of embellishments and their appropriate usages.

Schlagmanieren

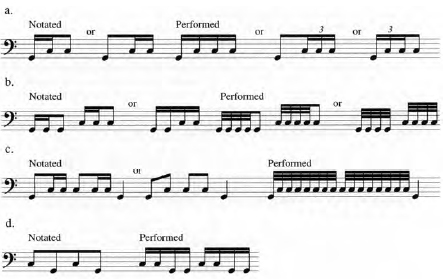

The term Schlagmanieren, or “beating ornaments,” is collectively applied to the ornaments employed in timpani performance practices of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.42 The simplest of these figures are gestures commonly used in the eighteenth-century timpanist's vocabulary. A second group (known as Schläge, or strokes) has to do more with visual effects than with sound. And a third, more complicated group comprises the Zungen, or tonguings—specifically formulated rhythmic diminutions of different patterns of written notes. In general, these figures should be coordinated with those of the trumpets and employed liberally, according to the timpanist's discretion, in order to embellish timpani parts as other parts were embellished during the Baroque.

Virtually the only one of the first group of embellishments generally used today is the roll. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, two varieties of this figure existed. First, there was the roulement, a rapid, unmeasured series of strokes on a single drum. Marin Mersenne described this figure as follows in 1636: “[I]t is first necessary to note that some beat the drum so fast that the mind or the imagination cannot comprehend the multitude of blows that fall on the skin like a very violent hailstorm.”43 Whether the roulement was executed with single or bounced strokes is uncertain; the type of stick used may well have influenced the decision more than considerations of sound quality.

The second type of roll was called the Wirbel—the usual modern German term for the unmeasured roll. Unlike the modern roll (and the Baroque roulement), the Wirbel was a definitely measured series of strokes between the two drums. Moreover, the illustrations of this figure in Altenburg's treatise demonstrate that the Wirbel existed in two forms, the einfacher Wirbel (simple Wirbel) and the Doppel-Wirbel (double Wirbel). As shown in Example 9.2, the only difference between these two was their different metrical structures.

Example 9.2. Wirbel and doppel-wirbel (from Johann Ernst Altenburg, Versuch einer Anleitung…, 129). Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig. Used by permission.

An important point concerning the use of the roulement and the Wirbel must be addressed here. Generally, performances of early music and studies of timpani performance practices continue to regard the addition of a roll (roulement) on the final note of a composition as the most authentic manner of execution. Contemporary evidence suggests otherwise, however. Speer, for example, says of the final-cadence: “Before the final cadence, the timpanist must always play a good, long Wirbel, and after this, just as the trumpets cut off, first play the last, and very strong, stroke on the drum tuned to c and placed to the right-hand side.”44

In other words, the material immediately preceding the final cutoff must be definitely measured and may be played between the two drums—quite the opposite of the roulement, whose notes should be indistinguishable and (presumably) played on a single drum. Speer also provided a musical illustration of this sort of ending, which he dubbed the “final flourish,” or final-cadence (Example 9.3).45

Example 9.3. Final-cadence (from Speer, Musikalisches Kleeblatt, 219).

But the roulement and Wirbel were not the only ways in which performers filled longer note values. If Altenburg's treatise is any indication, performers could also embellish a half note or whole note by means of any combination of quarter notes, eighth notes, or triplets. The only guideline seems to have been that the general contours of the passage should concur with those of the notated parts (for example, a passage in which a notated whole-note C is followed by a notated whole-note G should include C and G on the respective downbeats).

The second family of embellishments, known as the Schläge (strokes or beats), were characterized according to the idiomatically timpanistic technique involved in their execution. Conceptually, the simplest of these are the Kreuzschäge and Doppel-kreuzschläge (cross-stickings and double cross-stickings). As shown in Example 9.4a, the cross-stickings are a clear counterpart to modern triplet cross-stickings.46 The execution of the double cross-stickings, on the other hand, is more difficult: as shown in Example 9.4b, Altenburg's notation of two stems on the noteheads suggests that each note was to be played by striking the head simultaneously with both sticks—a notion that is borne out by descriptions of the figures as late as the mid-nineteenth century.47 In addition, the achtel- or einfache Schläge (eighth-note or simple strokes, Example 9.4c) evidently were to be played by striking the drums simultaneously with both sticks, alternating the strokes of each stick from half height to full height (a visual effect known today in the snare-drum technique as “half-switching”).

Example 9.4. (a) Cross-stickings; (b) double cross-stickings; (c) eighth-note or simple beatings.

The Schläge are telling indications both of the improvisatory nature of Baroque timpani performance practices and of the importance of visual—almost theatrical—techniques for realizing the parts authentically: since most involve techniques that in some way compromise the tone quality of the drums, intrinsically musical effects cannot be their raison d'être. Cross-stickings, though sometimes a musical necessity in the later repertory (as at the end of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony), are rarely necessary in the earlier literature; double cross-stickings are an even more explicitly visually conceived figure; and the einfache Schläge, with their dramatic half-switching of the mallets, clearly were designed to please the eye at least as much as the ear.

A more intrinsically musical motive led to the codification of the final group of figures, the Zungen (lit., tonguings), whose name obviously reflects the timpani's close affinities to the trumpets in terms of musical usages and performance practices. The Zungen are in fact nothing more than diminutions employed by the players of the lower trumpet parts (those notated at g–g' and commonly designated principal or quinta) and the timpanist, whose part generally doubled that of the lower trumpet rhythmically and melodically.

Contemporary sources suggest that six different Zungen were in use by the mid-eighteenth century. As shown in Example 9.5a–c, the einfache Zungen (simple or single tonguings) were performed by adding a single note to the original notated part, and the Doppel-Zungen (double tonguings) by adding two strokes to the original figure; the ganze Doppel-Zungen (complete double tonguings) were an extension of the Doppel-Zungen. In addition, the figure common in timpani parts could be embellished by means of the tragende Zungen (whose name presumably derived from the “carrying” motion created by moving the sticks rapidly between the drums without cross-sticking; see Example 9.5d). The timpanist's decision as to which of these diminutions should be employed was probably determined by factors such as tempo, rhythmic activity in the remainder of the ensemble, embellishments added by the trumpets or other instruments, and harmonic context—or simply his own invention.

Example 9.5. (a) Simple tonguings as notated and realized; (b) double tonguings as notated and realized; (c) extended double tonguings as notated and realized; (d) carrying tonguings as notated and realized.

CONCLUSIONS

The advent of notated percussion parts and the proliferation of treatises discussing percussion during the seventeenth century largely eliminated the first question that percussionists face in music of earlier centuries: when to play. Percussion instruments may occasionally have been used in the context of dance or other instrumental music;48 timpani could be used whenever trumpets were present; and trumpets could be added whenever a piece was performed to suggest a courtly or festive occasion.

Rather than face this issue, the performer dealing with a notated or ad libitum part in a piece of seventeenth-century music faces an issue that is at once more bewildering and yet more rewarding, too: how to realize the part in a historically authentic manner. The best response to this issue is to remember that there is no single best response. Variety and invention were as much the prerogative of the performer as they were of the composer, and aside from using instruments that had not yet come into existence, the only way to give an “inauthentic” performance was to perform strictly according to what was notated.

NOTES

1. Virdung, Musica getutscht: fol. 13r.

2. For further discussion of these issues, see Blades, Percussion; further, Blades and Montagu, Early Percussion; Montagu, Making Early Percussion; and especially Harms, “Early Percussion” in Kite-Powell, Renaissance.

3. Harms, “Early Percussion”: 161.

4. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle: 3. Percussion instruments discussed in Book 7, one of the “Books on Instruments” (trans. Chapman). Trichet's Traité des instruments de musique was first published under the editorship of François Lesure, in Annales musicologiques 3 (1955): 283–287, and 4 (1956): 175–248. Though the work was begun around 1630, the section on percussion presumably dates from after 1636, since in it Trichet refers to “Mersenne's book on instruments” (i.e., book 7 of Harmonie universelle).

5. Praetorius, Syntagma II: esp. 4, 78–79. Praetorius/Blumenfeld, Syntagma II: 4, 78–79; Praetorius/Crookes, Syntagma II: 23, 77–78.

6. Ibid.: 78–79.

7. For information concerning the emergence of national styles of playing field drums and tabors, see Tabourot, Historic Percussion, esp. 118–125.

8. Trichet/Lesure, Traité, 238–239; Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 53; Praetorius, Syntagma II, Theatrum instrumentorum: plates 23, 29.

9. Harms, Early Percussion: 162.

10. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 53; Trichet/Lesure, Traité: 238–239.

11. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 53; Trichet/Lesure, Traité: 239.

12. Trichet/Lesure, Traité: 238.

13. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: between pp. 56 and 57.

14. Ibid., 7: 53.

15. Virdung, Musica getutscht: [24]; Trichet/Lesure, Traité: 238.

16. Praetorius's Theatrum instrumentorum includes in plate 29 a set of “cymbals [Becken] that the Americans play like we play the bells”: a set of four graduated plate-shaped objects with indented bells, resting on a frame of long crossbars and suspended above the ground. Unfortunately, Praetorius provides no further information about these instruments.

17. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 49; Praetorius, Syntagma II: Theatrum instrumentorum, plate 40.

18. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 49.

19. Trichet/Lesure, Traité: 247; Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 49. A rare notated example of castanet music may be found in Feuillet, Choréographie: 100–102.

20. For a reproduction, see Blades, Percussion: 204.

21. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 3: 175–176.

22. The reference is to the instruments described in a letter to Dardanus supposedly written by St. Jerome. For a description of the letter and the instruments discussed in it, see Hammerstein, “Instrumenta”: 129–132.

23. Virdung, Musica getutscht: fol. 12v.

24. See Cooper, “Realisation and Embellishment.”

25. Speer, Grundrichtiger Unterricht. For a rather free translation of Speer's treatise, see Howey, Speer.

26. For a magnificent recording of this setting of In dulci jubilo, complete with an authentically realized timpani part, see the recording by Paul McCreesh under “Suggested Listening.”

27. The misattribution of the Mass was originally made by W. A. Ambros in the second edition of his Geschichte der Musik (Leipzig, 1881): 144. The first discussion referring directly to the timpani appears to have been Kirby, “Kettle-Drums.” Kirby's article was in turn cited by several widely read studies of percussion. Titcomb, “Kettledrums”: 154; Gangware, “Percussion”: 138; Peters, Drummer-Man, 48; Blades, Percussion: 236. For a concise overview of the corrected attribution, see Hintermaier, Missa Salisburgensis.

28. In the Traité de l'orchestration (1844), Berlioz stated that most orchestras still used only wooden sticks and wooden sticks covered with leather, and then asserted that the “most musical” effect could be obtained by using sticks with sponge ends. Berlioz also notes that sponge-headed sticks should be used when the works of the “old masters” specified that the timpani were to be covered or muffled, thereby distinguishing “modern masters” (presumably including himself) from those older ones. See Berlioz, Treatise: 380, 385.

29. Howey, Speer: 171–172; “Von den Paucken, deren Gebrauch und Mißgebrauch in alten und neuen Zeiten,” Wöchenliche Nachrichten und Anmerkungen die Musik betreffend 2 (1768): 216.

30. For an early example of these pictures, see the anonymous painting of trumpeters and timpani, ca. 1569, reproduced in Naylor, Trumpet and Trombone: plate 155. The painting, held in the Badische Landesbibliothek, Karlsruhe, shows a timpanist using sticks covered with what clearly appears to be a soft, textured material.

31. Virdung, Musica getutscht: 25; Praetorius, Syntagma II: 25.

32. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle: 51; “Von den Paucken”: 208.

33. Altenburg, Versuch: 123 [recte 132]. A digital reproduction may be accessed at http://books.google.com/books?id=in4vAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=altenburg,+versuch+einer+anleitung&source=bl&ots=tzPPU2obqB&sig=cqbYLTmEk00xmFdMQ_DX_EjGfOc&hl=en&ei=SQKkTMuVMITGlQfwusDyCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBcQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

34. Praetorius, Syntagma II, Theatrum instrumentorum: plate 23.

35. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 54.

36. On the use of multiple timpani in the Baroque repertory, see Cooper, “Performance Practices,” 78–81. A little-known early nineteenth-century example of a prominent solo for three timpani is found in the Piano Concerto in ![]() Major by Ignaz Moscheles, in which the timpani state the subject, solo, in the first movement. For a reproduction of this solo, see Allge-meine Musik-Zeitung 24 (1821): 550.

Major by Ignaz Moscheles, in which the timpani state the subject, solo, in the first movement. For a reproduction of this solo, see Allge-meine Musik-Zeitung 24 (1821): 550.

37. Eisel, Musicus autodidacticus: 66.

38. For a useful overview of the pitch differences effected by different beating spots, see Rossing, “Acoustics”: 18–30, esp. 22, 25–26.

39. My own experience indicates that when one uses Baroque-sized timpani and beats in the center of the drum in a chamber made mostly of wood or stone, that is, the indoor acoustic context in which the timpani were usually employed through the high Baroque, the sound is more like that of a pizzicato cello or double bass than of a timpani struck at the normal beating spot.

40. Indeed, the centralization of French musical life that occurred under Lully in the latter part of the seventeenth century certainly would have fostered the specific notation of all desired parts, simply in order to ascertain that those parts were not omitted in performance.

41. A good example of this kind of exception is the introductory timpani solo of Sebastian Bach's Christmas Oratorio, which in its original version in BWV 214 would have lent itself to free improvisation. For a discussion of this part, see Cooper, “Realisation and Embellishment.”

42. The usual translation of this term, “manners of beating,” is insufficient because it neglects that in eighteenth-century German, Manieren was the usual term for ornaments.

43. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle 7: 56.

44. Speer, Kleeblatt: 219ff. The mention of the c drum standing on the right-hand side indicates that Speer was speaking from the viewer's perspective, not the timpanist's (who would have said that the c drum was placed to the left). Speer's statement was echoed almost verbatim, but with the placement of the drums corrected, in Eisel, Musicus autodidatus.

45. Speer's decision to notate the part at C and g, a tuning seldom encountered in the actual Baroque literature, reflects the traditional treatment of the timpani as transposing instruments. This example would best be regarded a written for timpani in G, in effect, drums tuned to G and d.

46. Cross-stickings are necessary here because the timpani were positioned with the smaller drum (c) at the player's left hand and the larger one (G) to the right.

47. See, for example, Bernsdorf, “Doppelkreuz-Schlag,” in Neues 1: 712. Isolated examples of this technique occur at the beginning of the “March to the Scaffold” in Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique and the third movement (mm. 318–322) of Mahler's Fourth Symphony.

48. Berthold Neumann argues that percussion instruments were not widely used in polyphonic dance music. See Neumann, “Kommt pfeift,” and responses to it by Ben Harms and Peggy Sexton in Historical Performance 5/1 (Spring 1992): 32–34.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Altenburg, “Versuch”; Avgerinos, Handbuch; Avgerinos, Lexikon; Beck, Encyclopedia; Berlioz, Treatise; Blades, Percussion; Blades/Montagu, Early Percussion; Bowles, “Double”; Bowles, Timpani; Bowles, “Using”; Cooper, “Performance Practices”; Cooper, “Realisation and Embellishment”; Eisel, Musicus; Hardy/Ancell, “Comparisons”; Harms, “Renaissance”; Hintermaier, Missa Salisburgensis.; Kirby, “Kettel-Drums”; Mersenne, Harmonie universelle; Montagu, Making Early Percussion; Neumann, “Kommt”; Powley, “Little-Known”; Rossing, “Acoustics”; Tabourot, Historic Percussion; Trichet, Traité.

Suggested Listening

Michael Praetorius. Mass for Christmas Morning, Paul McCreesh and the Gabrieli Consort and Players, Deutsche Grammophon Archiv CD 439 250–2.