![]()

Basso Continuo

The term basso continuo designates a mode of accompaniment in use primarily between 1600 and 1750. Continuo practice embraces a wide spectrum of activities and styles, but all such accompaniment includes one thing in common: at least one player of any continuo part produces harmony, the choice of which the composer has designated or the music suggests, but the exact notes of which are left up to the performer. Thus a continuo part has two components: a bass line, which is provided by the composer and is generally to be performed as notated (except for possible octave displacements and restriking or tying of bass notes), and a set of harmonies, which may be specified by signs or implied by standard chord progressions within a given style; the notes that produce these harmonies are not written out, but are rather improvised by one or more players.

The idea of adding a chordal accompaniment to vocal or instrumental pieces had been practiced in one way or another for over a century, either by improvisation or by reading “short score” (meaning that the keyboard player or lutenist plays the notes sounded by the various parts, rather than an improvisatory realization), but the practice grew with special intensity in the declining years of the sixteenth century as musicians began writing—and publishing—such music in the convenient shorthand method of figured (and unfigured) basses. As the practice spread, it was applied to older-style polyphonic textures, as well as to the newer ones of solo melody. Readers may consult A Performer's Guide to Renaissance Music (Schirmer Books, 1994; 2nd ed. Indiana University Press, 2007), an earlier volume of this series, for a segment sketching the historical development of basso continuo.

ACCOMPANYING SOLOISTS

When Vincenzo Galilei learned, at first to his horror, that Girolamo Mei's research into Greek music indicated that the texts were sung without accompaniment, he knew that modern songs could not be sung literally solo even if it was the surest way to achieve a proper affect. European ears were too used to harmony by this point; Pietro de’ Bardi reports that Galilei himself set a passage from Dante, presumably to be sung in the new style and “precisely accompanied by a consort of viols.”1 It soon became clear that when working with singers, the best way to provide flexible, expressive accompaniments was on a lute—or, more particularly, the chitarrone. Sigismondo d'India, Jacopo Peri, Vittoria Archilei, and many others sang to their own accompaniment on the chitarrone, surely the most sensitive way to match accompaniment with solo. The early books of solo song, beginning with Caccini's Le Nuove musiche of 1602, recommend the chitarrone as the favored accompanying instrument, with harp and harpsichord as suitable alternatives.

Instrumental soloists had been accompanied in various contexts throughout the sixteenth century. In its last twenty years or so, a specific repertory developed for virtuoso players, especially of the cornett, recorder, and viola da gamba, who would play (or improvise) elaborate ornamental passages based on a polyphonic piece such as a madrigal, chanson, or motet. In his Tratado de glosas, Diego Ortiz gives instructions for this practice as early as 1553, and further examples are seen down through the end of the century. An entire style and repertory of viol music—that for viola bastarda—was built on this approach; it, too, is a style of instrumental solo playing with accompaniment, generally provided by a keyboard or lute player using the polyphonic piece as a model.2

ORGAN BASSES

In the choir loft, organists accompanied their choirs for sonority as well as to help them stay together—and in tune—more easily, especially in the multichoir pieces newly popular in Rome and Venice, where each choir might have a separate organ assigned to it. At first, these “accompaniments” simply doubled the singers’ music, but in 1602 Lodovico Grossi da Viadana's Cento concerti ecclesiastici documented a newer practice in which the organist was given only a bass line over which harmonies were to be added, rather than simply doubling all of the vocal parts. This notational shorthand eventually freed continuo players from doubling the vocal parts and encouraged a simpler, chordal accompaniment that provided more rhythmic freedom to the singers as well, since their parts were no longer being doubled. The organ part thus became a separate, integral, and indispensable part of the music, where previously it had been used simply to enrich the sound and/or help the performers. It is for this reason that Viadana's work is generally cited as the first to use basso continuo; in any event, this is the first writer known to use the term in print.

LARGE CONTINUO ENSEMBLES

Accompanimental textures were not limited to just a few instruments. We know from the recorded practice of the Florentine intermedii, from the Ferrarese concerto grande, and from the writing of Agostino Agazzari that it was popular to accompany large ensembles with a variety of instruments, each contributing its most interesting characteristics (e.g., the chitarrone's sonorous low bass strings, long drawn-out chords on the lirone, scales and ornaments gently plucked over the whole range of the harp, etc.). Agazzari explains that accompanying instruments are divided into two types: instruments of foundation (such as harpsichords, lutes, and organs) to provide the basic chordal harmonies, and instruments of ornamentation (such as violins and lutes, now playing melodically) to improvise ornaments based on the harmonies and general shape of the music.

Continuo batteries remained a basic and popular texture for most of the seventeenth century. In addition to specific examples, such as Claudio Monteverdi's Orfeo (1607), with its three chitarrone, ceteroni, harps, two harpsichords, organ, and regal, and Luigi Rossi's Orfeo (1647) with four harpsichords, four theorbos, two lutes, and two guitars, we have generic combinations peculiar to specific countries, such as the organ and theorbo in England, or the harp and guitar in Spain. In fact, it would seem that continuo ensembles of five to ten players were not uncommon. In 1683 one observer remarked that in Venetian opera houses it was difficult to see the action on stage “because of the forest of theorbo necks.”3

PERFORMANCE

Continuo accompaniment requires one or more chordal instruments, the choice and number depending on the size of the performance space, how many people are being accompanied, and what they are doing. In addition, different repertories and musical styles sometimes entail the use of specific instrumental combinations, as suggested above. Incidentally, it should also be noted that not all “continuo parts” were necessarily intended for players: in his Musicalische Exequien (1636), Heinrich Schütz provides a bass part labeled for either the “violon or the director (Dirigent).” This would seem to be a part that could be used by the player of the lowest line, or, in lieu of a full score, by a leader to help keep track of the proper harmonies.4

DOUBLING THE BASS LINE

It has long been thought that continuo in Baroque music involved two components, a chordal instrument (harpsichord, organ, lute, etc.) and a sustaining instrument (cello, viol, bassoon, trombone, etc.). While this classic “team” does appear to have been standard for later Baroque music, the use of a bowed bass instrument to double the written bass line is no longer considered standard for music of the seventeenth century.5 The situation is complicated and varies from repertory to repertory but can be summarized as follows: secular solo song was originally conceived for voice and lute or chitarrone and does not require or benefit from the addition of a bowed bass in most cases up until the very active bass lines of the second half of the seventeenth century. There are several reasons for this: (1) the bass lines at this time are largely unmelodic and simply represent the lowest note of the harmony; (2) the decay of a plucked sound gives the singer a transparent texture over which to deliver the text clearly; and (3) the fewer performers involved, the more flexible the performance can be, which is undoubtedly the reason Caccini and others considered self-accompaniment the ideal for the repertory. Bass-line doubling was practiced in special cases (e.g., Monteverdi's Combattimento), or used in the theater for more carrying power. In England many lute songbooks include a part for bass viol, but there is no evidence the practice continued after John Attey's collection of 1622, or that it was more than an option in the first place. In the sacred repertory, Viadana makes it clear that he assumes the organ to be used as standard accompaniment. No mention is made of a bowed bass, nor would its use have been assumed at this time. The organ was frequently doubled by a chitarrone, however, providing a clearer bass than the organ can produce on its own. The combination of organ and chitarrone was a very popular one, as may be seen in surviving church documents and accounts of performances.6

Archlutes and theorbos were considered melodic bass instruments as well as continuo instruments and often doubled the bass line in addition to playing chords. This is important to keep in mind, since most of the discussion about bass-line doubling over the past quarter century has centered on the question of doubling by sustaining instruments, such as bass viol, cello, or bassoon. For much of the seventeenth century, doubling by a plucked instrument was preferred, since it provided clarity without muddying the texture. Situations in which sustained instruments were used to double the bass line usually involved either highly active lines, or acoustical environments that required an especially strong bass, as in large churches (e.g., Heinrich Schütz, Michael Praetorius, Andreas Hammerschmidt, the Roman oratorios, Maurizio Cazzati, etc.) or in theater venues (English masques, Italian opera, etc.).

In fact, the whole idea of doubling seems to have arisen in situations either where the bass needed extra clarity or support, or where the music needed extra emphasis, as in the few bars of Monteverdi's Orfeo where it is specified. Nearly all of the evidence for doubling in the first half of the century is found in reference to large concerted music performed in churches; it seems to have been the exception rather than the rule. Concerted music with voices and strings (including Monteverdi's Eighth Book of Madrigals; Johann Rosenmüller, Giacomo Carissimi, and many other German and Italian sources) make it clear that bowed bass instruments normally played with the strings but not with the voices. This sets up a clear antiphonal effect: voice(s) with continuo, contrasted with strings and continuo. When the bass is doubled throughout, this structure is lost. An interesting exception to this is the Italian practice of a string ensemble improvising a chordal accompaniment over the bass, as discussed by Agazzari and indicated by Domenico Mazzocchi, Francesco Cavalli, and others.7

Many modern performers of seventeenth-century music fail to recognize that bowed bass players of the period often had their own independent partbooks and did not automatically play from the “continuo” book; Monteverdi's Vespers (1610) and Eighth Book of Madrigals (Madrigals of Love and War, 1638) provide two well-known examples. Italian collections of sonatas (Biagio Marini, Dario Castello, Giovanni Battista Fontana, etc.) included a partbook for bowed bass, which plays only when there is an independent part. In fact, the bowed bass partbook rarely includes the bass of the continuo until much later—indeed, as late as 1697, Bernardo Tonini suggests that a cello may double the bass line ad libitum.8 The whole question of bass-line doubling must be considered on a repertory-by-repertory basis.

BASSES FIGURED AND UNFIGURED

As the practice of providing accompanists with only a bass line caught on, composers and theorists used different ways to indicate the harmonies. Many basses were provided without any figures, on the assumption that players would be able to supply appropriate harmonies based on the line itself (and by listening to what was going on above); some theorists (e.g., Francesco Bianciardi, Alessandro Scarlatti, and Bernardo Pasquini9) devote a relatively large amount of space to teaching this skill.

In any event, the earliest use of figures (both numbers and signs) is sparse, and at no time can we assume that all figures are necessarily given, nor are octaves or rhythmic placement precisely specified. The figures are an aid to sensitive accompaniment, not a prescription of a keyboard part. In Italy, after bass lines had been published with figures for a few decades, players evidently developed this sensitivity to a high degree, for continuo lines began appearing there (again) with no figures.

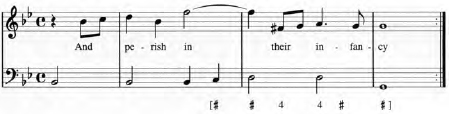

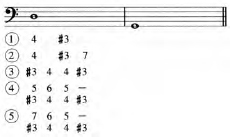

So players must be aware that virtually all continuo parts, practically speaking, are only partially figured to a greater or lesser extent. Sometimes the missing figures are obvious, but often more than one solution exists, lending the performer freedom to come up with expressively creative solutions. (A particularly interesting case is Matthew Locke's How Doth the City, for which John Blow published a continuo part and for which we also have Locke's own performance copy, with additions in his own hand. Locke added harmonies the original could never be thought of as suggesting.10) Many writers give advice for handling figureless passages and/or single notes in characteristic positions—for example, a bass line rising a half step generally calls for placing a first-inversion triad on the first note; the penultimate note of a cadence, if it drops a fifth or rises a fourth to the final note, should by convention be figured in one of the ways shown in Example 17.1.

Example 17.1. Conventional patterns for realizing a falling fifth at a cadence.

A solitary sharp or flat used alone, without a numeral, simply means to raise or lower, respectively, the third above the bass note. Thus, in a part with one flat in the signature, a G with a sharp above it indicates a G-major chord. Also, note that continuo figures serve as reporters of the harmony as much as they indicate what to actually play: every figure does not need to be played even if present—especially when accompanying soloists.

BASSO SEGUENTE

A basso seguente is a composite line consisting of the lowest-sounding part at any given moment, whether the notes of the written bass line or not. If you are playing continuo from the bass line, there may be passages where it rests—and therefore the accompanying ensemble rests, as well (basso non-continuo, as it were). Accompanists playing from a basso seguente part, on the other hand, continue playing at all times, for as a serial compilation of whatever is the lowest-sounding line, it never stops. Adriano Banchieri mentions and describes this practice in 1607, also calling it barittono.11 When an upper line momentarily became the functional bass, it was referred to as a bassetto and generally was to be played in its proper octave and not one octave down; the relevant measures appear in the basso continuo part, but in the “home” clef of the visitor. (Schütz provides an exception when he mentions in the Musicalische Exequien [1636] that if a part is in alto or tenor clef, such as a trio for two sopranos and alto, the Violon may double the lowest-sounding part an octave down.)

POINTERS ON STYLE

There is no one package of stylistic advice that can accommodate all Baroque music; however, several basic principles surface consistently.

The essence of continuo playing is to provide harmony and rhythm, and to provide gestures that match or complement the solo part(s). Continuo players need to shape and inflect lines, using crescendos, diminuendos, messe di voce, and esclamationi, together with the voices and instruments being accompanied. The playing should be spontaneous, inventive, and interactive. Continuo playing that strives merely to stay out of the soloist's way actually makes it more difficult for singers and string players to create the kinds of affects required in early Baroque music, since a flat, neutral shape counteracts a highly inflected one. At the same time, hyperactive continuo playing diverts attention from the solo parts and usually works at cross purposes with them. As Bénigne de Bacilly observed in 1668,

If the theorbo isn't played with moderation—if the player adds too much confusing figuration (as do most accompanists more to demonstrate the dexterity of their fingers than to aid the person they are accompanying) it then becomes an accompaniment of the theorbo by the voice rather than the reverse. Be careful to recognize this, so that in this marriage the theorbo does not become an overpowering, chiding spouse, instead of one who flatters, cajoles, and covers up one's faults.12

Four parts is the norm, but to imitate the shape and gestures of the solo line(s), the texture of continuo chords needs to be as varied as possible—according to Bianciardi and Giovanni Domenico Puliaschi13—with full chords for strong beats, strong syllables, and dissonances, and thinner chords for weak beats, weak syllables, and resolutions. Constant four-part texture is useful as an exercise in voice leading, but it creates a relentless texture and prevents dynamics or inflection on harpsichords or organs. The thickness and complexity of the accompaniment should also match the forces at hand—full ensembles generally require four-part harmony and more, but for soloists one must often reduce the number of notes in the right hand, a practice recommended by Agazzari (1607), Praetorius (1619), Wolfgang Ebner (1653), and Lorenzo Penna (1672).14

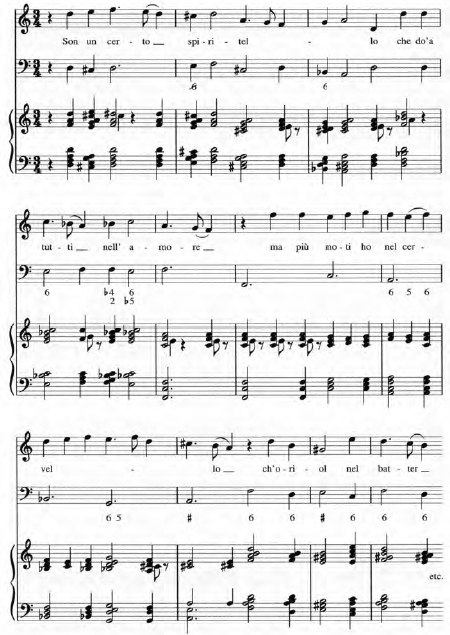

Example 17.2. Dieterich Buxtehude, Fürchtet dich nicht, BuxWV 30, Sonata, mm. 1–11. Reprinted with permission of Schirmer Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Macmillan from Dieterich Buxtehude: Organist in Lubeck by Kerala J. Snyder: Copyright © 1987 by Kerala J. Snyder.

When using the organ, players must also be careful about registration. Schütz has specific suggestions for this, cautioning his players only to use a still Orgelwerk (“soft organ registration,” suggesting flutes) in the Musicalische Exequien so that the words might be understood.15 In the Psalmen Davids he also recommends using differing registrations (soft and loud) to underscore the differences between the small and large groups of singers (Favorito and Capella, respectively;16 see Schütz, Psalmen Davids, 1619;17 this advice is echoed in Praetorius, as well).18 Viadana takes a different tack, noting that volume should be controlled by varying the thickness of keyboard texture, not by adding/subtracting stops.19

DOUBLING THE BASS AN OCTAVE DOWN

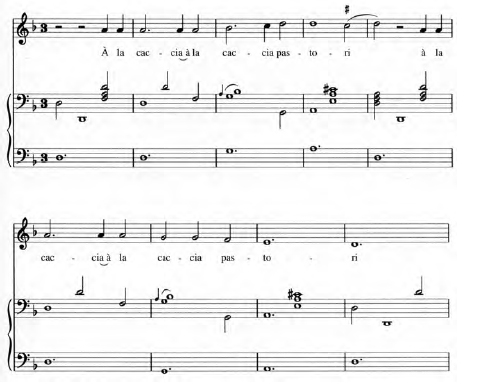

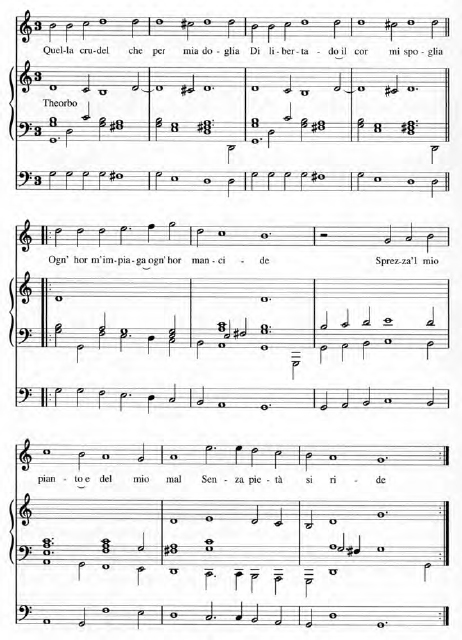

Several writers suggest that the bass line can be played or doubled an octave lower to provide a richer sonority.20 Alessandro Piccinini considered the contrabassi to be the soul of the chitarrone and the archlute and recommended that they be used as much as possible.21 Existing seventeenth-century realizations make extensive use of this sixteen-foot register (see Examples 17.2 and 17.3).

Example 17.3. Angelo Notari, A la caccia.

Example 17.4. Bellorofonte Castaldi, Capricci a due stromenti cioè tiorba e tiobina (1622).

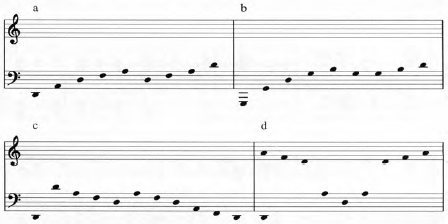

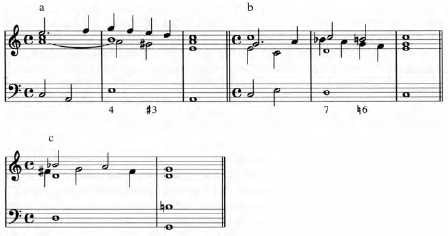

ARPEGGIATION AND OTHER TIME FILLERS

If the sound dies away (as on a harpsichord or lute), restrike chords, or notes of chords, as necessary to keep some sort of presence.22 Girolamo Frescobaldi and Penna both recommend to “spread the chords (arpeggiare), in order not to leave a void in the instrument.”23 Vary the speed and pattern of arpeggios, mixing them with block chords according to metric placement, rhythmic function, note values, and so forth. Use slower, fuller arpeggios to fill out long notes, and quicker rolls for shorter, more rhythmic chords. One common way to fill up a long note is to roll a chord on the downbeat and play the bass down the octave in the middle of the bar (see Example 17.4).

Place bass notes firmly on the beat, rolling the chord afer the note.24 Pianists and guitarists often learn to anticipate the beat with the bass and its rolled chord in order to put the treble note on the beat. This approach is inappropriate in continuo playing, as it puts the bass before the beat and creates serious ensemble problems. It is unfortunately a difficult habit to break. Arpeggios can go from the bottom up, or from the top down (usually with the bass not played together with the top note in that case), or may start with the bass and then jump to a higher pitch and proceed down and back up again (see Example 17.5).

Example 17.5. Sample arpeggio patterns for continuo realization.

In dance music, long cadential notes often require a rhythmic filler, as can be seen in the cadences of solo pavans or courantes, for instance (see Example 17.6).

Example 17.6. Sample cadential patterns for continuo realization.

Another common method of expanding chords is through the addition of acciaccature or passing tones, which could either be used to enrich an arpeggio or add spice to a block chord25 (see Example 17.7).

Example 17.7. Continuo realization of an aria, ca. 1700, from Anonymous, Regole…d'accompagnare (Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense MS RI; reproduced in Borgir, Performance, 134). Reprinted by permission.

REGISTER AND AFFECT

Bianciardi recommends varying the register to suit the affect—for example, a low register for doleful music, a higher one for more animated passages. In essence, seventeenth-century sources advocate imitating the affect and inflection of the words as much as possible through varying the timbre, dynamics, register, chord voicing, articulation, and shaping. Thus harsh, bright colors may be used for “anguish,” “pain,” or “torment”; beautiful sounds for “sweetness” or “pleasure”; low, earthy colors for “earth,” “hell”; high celestial sounds for “heaven,” “angelic.” Recent scholarship also documents that extreme, unprepared, and unresolved dissonances, as well as acciaccature and other such features, were widely used in Italy to better convey affect in vocal music.26

DOUBLING THE SOLOIST

Opinions vary on this. Many writers echo the opinion of Agazzari, who suggested in 1607 that one should “be careful to avoid as far as possible, the same note which the soprano is singing, and not to make diminutions on it, so as not to double the voice part and obscure the goodness of the said voice…therefore it is good to play within quite a small compass and low down,”27 while Penna (1672) suggests doubling a part if it is sung by a soprano or alto28 and Johann Staden (1626) says that you should try to avoid doubling the soprano, but that it is not always possible.29 The implication is that solo parts should not be doubled consistently, but that doubling the odd note is unavoidable, except in sacred vocal polyphony or English viol fantasias (William Lawes, John Jenkins, etc.), in which the organ plays a short score of all the parts.

The question extends to dissonances and thirds as well. Andreas Werckmeister (1698) cautioned:

It is also not advisable that one should always just blindly play, together with the vocalists and instrumentalists, the dissonances which are indicated in the Thorough-Bass, and double them: for when the singer expresses a pleasing emotion by means of the dissonance written, a thoughtless accompanist may, if he walk not warily, spoil all the beauty with the same dissonance: therefore the figures are not always put in order that one should just blindly join in with them; but one who understands composition can see by them what the composer's intention is, and how to avoid countering them with anything whereby the harmony might be injured.30

This passage is a reminder that figures are frequently “descriptive” of the harmonies in solo parts and not necessarily “prescriptive” of what the continuo player should play. However, beware of the “table-scraps” school of continuo playing, an approach that forbids the doubling of all dissonances and thirds and requires the accompanist to avoid all notes in the solo part(s), playing only what is left over. The problem with this manner of playing is that it forces the player to concentrate on what not to play, rather than on how best to make appropriate gestures. While exposed thirds and dissonances are often better left to the soloist, habitually avoiding them leaves the continuo player with the fewest notes to play at the moments of greatest tension, the opposite of what is musically required. It is both awkward and unnatural to avoid them rigorously; indeed, written-out parts of the period indicate that players often doubled thirds and dissonances in the interest of creating the most sonorous and inflected lines possible. (Thirds sound less obtrusive if doubled in a lower octave, rather than at the top of a chord. This also makes intonation less tricky.)

Dissonances may be doubled for more bite, even in octaves for extra emphasis, but resolutions are best left to the solo part(s) to lighten the moment of resolution. A full chord with the dissonances doubled can then be contrasted by thinner chords on the weaker beats to achieve an effective hierarchy between tension and relaxation. Dissonances cannot be convincingly conveyed when the continuo plays only a root and fifth, because there is often not enough sound for the soloist to rub against. Such a texture is also too thin to give the dissonances the pungency they require. In meantone temperament bare fifths are quite sour, which is probably the reason they so rarely occur in solo lute and keyboard music of the period. In addition, written-out accompaniments usually double dissonances rather than avoid them. Some sources show continuo instruments playing a major triad against a 4–3 suspension in a solo part, or a 6 chord against a 7–6. This is another way to create a strong clash on the dissonances to add to the continuo player's bag of tricks.31

At the same time, beware the idea of consistently doubling everything and/or adding constant rhythmic subdivision at the top of the texture, as one sometimes hears. While there is evidence of very full-textured playing in the eighteenth-century sources, mainstream seventeenth-century practice does not appear to have involved such extreme doubling and subdivison, which has the effect of straitjacketing the soloist(s), especially in recitative music.32 In Italian monody, for instance, the continuo player needs to give the singer as much rhythmic freedom as possible by not adding subdivisions or runs that force his or her hand. Runs are generally distracting in continuo playing except as a special effect (e.g., for flashes of lightning or a torrent of water), or as a link connecting one section of a piece with another, especially in dance music.

This brings up another crucial but rarely discussed feature of early Baroque continuo practice: it seems likely that continuo players generally played standard harmonic progressions for most of the seventeenth century, allowing composers to add extraordinary dissonances and “blue notes” in the solo parts to clash against the accompaniment (see Example 17.8, especially the downbeat of the third measure). Editors and scholars are often puzzled by these dissonances and sometimes try to realize extraordinary harmonies to take them into account. In fact, based on the figuring in original sources and surviving realizations, it seems clear that these blue notes were not to be realized, but that they represent a special kind of dissonance designed to clash against straightforward harmonies.

Example 17.8. Henry Lawes, Sweet Stay Awhile (figures editorial).

CADENCES

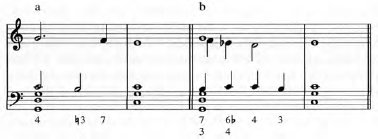

Seventeenth-century cadences generally involve 4–3 or 7–6 suspensions; however, these were elaborated in a variety of interesting and often daring ways. While dominant–tonic movement in the bass was nearly always harmonized with a 4–3 suspension, a seventh could be added after the third, or a third before the fourth. This allows the possibility of playing a flatted sixth with the fourth, or even of adding a seventh to the first third (see Example 17.9).

Example 17.9. Sample realizations for cadential suspensions.

The English had a particular predilection for false relations in cadences, as may be seen in John Blow's examples for accompanying standard cadences that include flatted thirds and sixths on the downbeat of the penultimate bars, forming most telling dissonances with the “operative” notes of the passage called for by the figures.33 A flatted sixth over a dominant can be harmonized with a major third going to a fourth in addition to the more usual six–four harmony (see Example 17.10).

Example 17.10. John Blow, sample realizations for cadential suspensions.

Many writers mention that final cadences (or medial cadences of any importance) should be taken with a major third, whether called for by the figures or not. This advice spans the century from Agazzari (1607)34 to Locke (1673).35 The minor third was an imperfect interval and was generally avoided in cadences except in overlapping imitative entrances, and in France. Friedrich Niedt explained, “I know very well, it is true, that French composers do the opposite, but everything is not good just because it comes from France.”36 In some situations, an open chord (without a third) is indicated in string or voice parts, providing the continuo player with an alternative to playing every cadence major. In Restoration England, cadences of all three varieties are found: major, minor, and open, giving the continuo player options according to the desired effect.

CONTRARY MOTION

On a keyboard, the overall effect should be of the right hand playing in contrary motion to the left. Virtually all writers mention this; Penna (1672) adds that if it is not possible, then the right hand should play parallel tenths with the bass, certainly an easy way around many difficult passages.37

PARALLEL MOTION

Many writers agree that while parallel fifths and octaves should be avoided in composed music, they are not particularly noticeable in continuo improvisations and should not be worried about unduly. As Viadana writes, “The Organ part is never under any obligations to avoid two Fifths or two Octaves, but those parts which are sung by the voices are” (1602).38 However, do be careful to avoid parallels between the outer voices or, slightly less problematically, between an inner voice and an outer one.

BASS RUNS

When the bass line has diatonic runs, chords should be played on the first notes of groups (e.g., four or eight), depending on the speed of the piece and the note values. Locke (1673) adds that you may substitute parallel thirds or tenths in the right hand for chords, and that the theorbo player need not play chords at all.39 Plucked instruments may strum the harmony in the rhythm of the bass line to produce more direction in the line if desired.

When the bass line moves by skip, each note may require its own chord, although in practice the speed of the piece determines how many chords can be played—the faster the speed, the fewer the chords. In any event, chords in the right hand of a keyboard part should be taken with as many common notes between them as possible. Werckmeister suggests that “when the Bass leaps, the other parts should some of them remain stationary, or only rise and fall by step with the leaping Bass.”40

ADDED ORNAMENTATION

Some specific suggestions about ornamentation as culled from period sources may be useful to help set the stage for a discussion of the nature of a good continuo part. Viadana (1602) and Girolamo Giaccobi (1609) suggest adding some passages, while Agazzari (1607) says to avoid inordinate scales and runs but that some ornamentation is allowed;41 he specifically mentions gruppi, trills, and accenti.42 Banchieri (Eclesiastiche sinfonie, 1607) admonishes the player to not ornament the bass line,43 while Francesco Gasparini encourages it.44 An Italian theorbo manuscript in Modena provides pages of elaborately ornamented cadences,45 while Thomas Mace's examples (1676) indicate a somewhat less florid approach. Praetorius (1619) recommends ornamentation on the organ if one is using a bright registration but to forego it when accompanying on the regal,46 and Schütz writes in 1623 that the organist and/or violist should add runs and embellishments when a singer holds or repeats a note.47 If the solo line is in the bass register, the continuo part will often be a less elaborate skeleton thereof and should not be ornamented. Penna (1672) mentions that “With a Bass, one may indulge in some little movements, but if the Bass has passages, it is not good to move at the same time”; nor should one make divisions at all if the soloist is a soprano, alto, or tenor.48 Penna also gives detailed advice on the playing of cadential trills in either or both hands, which one presumes was a standard addition through the century—yet Penna's suggested trills are anything but standard.49

See also the section Independent Contributions of the Accompanist, below.

IMITATIVE ENTRANCES

Concerning imitative sections, writers agree that the accompanist should double the first voice entering without supplying chords. Heinrich Albert (1640) says that chords should begin with the second entrance;50 Penna (1672)51 and Bartolomeo Bismantova (1677)52 declare that chords should not begin until all voices have had their entrance, with each line of counterpoint doubled by the keyboard player. Viadana notes that after doubling the first entrance without chords, it is up to the accompanist to decide whether to add them or not.53 Schütz would literally underscore the bass entry in an imitative texture by having the violon remain silent until the bass makes its entrance, and then doubling it.54 Eighteenth-century writers confirm that all fugal entries should be doubled on the keyboard, without chords, and there is no reason to doubt that it was not fairly standard practice in seventeenth-century music as well. Fugal movements require a knowledge of counterpoint, so that the accompanist will be aware of those places where entrances in inner parts cannot be indicated in the continuo parts but would have been expected.

TASTO SOLO

One special effect in eighteenth-century music is to have the keyboard player play single notes in the bass line without supplying any harmonies. This effect, called tasto solo, is not found in seventeenth-century keyboard sources except in the case of imitative entries, although Galeazzo Sabbatini's system (1628) does include playing the odd individual note without chords.55 Some theorbo accompaniments of Bellerofonte Castaldi and Johann Hieronymus Kapsberger also have such passages.

INDEPENDENT CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE ACCOMPANIST

Agazzari and Penna, writing at opposite ends of the century (1607 and 1672), both suggest that the accompanist might imitate something just heard in the soloist's part.56 Taking advantage of opportunities to answer a motive introduced by a soloist increases interaction while avoiding distraction. In southern Italy this developed into a practice known as partimento, in which common figures in the bass were answered in kind in the treble, or vice versa. Neapolitan treatises included systematic exercises to familiarize students with the most common situations (see Example 17.11).57

CHOICE AND NUMBER OF INSTRUMENTS IN THE CONTINUO ENSEMBLE

Instrumentation in early Baroque opera grew out of the tradition of the sixteenth-century intermedii, in which a great deal of symbolism was associated with various instruments. Thus wind instruments accompanied Neptune and sea monsters, pastoral characters were accompanied by recorders, Bacchus with crumhorns, Orpheus with the harp or lute, and so forth. According to Emilio de’ Cavalieri, in the preface to his Rappresentatione di anima, e di corpo (1600), continuo scoring should change according to the affect, not necessarily according to who is singing. Thus a monochromatic character such as Caronte, in Monteverdi's Orfeo (1607), is accompanied by the regal, while Orfeo, who goes through an enormous variety of emotions during the course of the opera, is accompanied by organ alone, organ and chitarrone, harp, strings, and so forth. According to scorings suggested in seventeenth-century sources, as well as contemporary comments made about different instruments, the following summary is suggested:

Chitarrone. For expressive music, recitatives, laments, light dances, and the like. The theorbo was listed as the preferred instrument to accompany solo song in Italy and France for the first half of the century and in England until 1687, when the harpsichord is listed first on a title page for the first time. The chitarrone was also widely used to accompany dance music and ritornelli for one or two violins (e.g., Biagio Marini, Scherzi; Salamone Rossi, Gagliarde, etc.).

Example 17.11. Francesco Durante, solo partimento exercise (from Partimenti, ossia intero studio di numerate (Bologna, Museo Biblografia Musicale, MS M.14–7; reproduced in Borgir, Performance, 143). Reprinted by permission.

Harpsichord. For rhythmic music, moments of turbulence (Orfeo, Acts 2 and 4), martial music (Monteverdi's Combattimento), and neutral characters (such as the shepherds in Orfeo). This is not to say that harpsichords never accompanied expressive music; they clearly did. The harpsichord was usually listed as the second choice after the chitarrone on title pages of Italian monody collections and English songbooks until the last decade of the century. Sources suggest, however, that the dynamic and timbral variety of the chitarrone was preferred for delicate, expressive music.

Guitar. For light vocal music, dances, and comic characters in the theater.

Organ. For serious and tranquil moments; often coupled with the chitarrone. The organ was widely used in operatic productions at court, as well as in secular chamber music, as Monteverdi makes clear in a letter from June 2, 1611, describing the use of chitarroni and organ to accompany madrigals. To what extent organs were used in commercial theaters is not yet known. In England the combination of organ and theorbo was the standard continuo group in consort music.

Regal. For underworld figures, bizarre characters, bass voices.

Lirone. For laments, often with a bowed bass or chitarrone to supply the bass line.

Harp. For celestial music, music of the gods.

Strings realizing a chordal “accompagnato.” Used to highlight moments of special importance (e.g., “Sol tu nobile Dio” from Monteverdi's Orfeo; Cupid's “Ho difeso” in Poppea; “Amico hai vinto” from the Combattimento; the first performance of Lamento d'Arianna).

Seventeenth-century musicians tended to typecast instruments to a certain extent, especially in the theater, avoiding the weaknesses of each instrument as much as possible. Of course, performers strove to overcome these weaknesses in order to be able to express the greatest variety of affects on each instrument. It is insulting to suggest to harpsichordists that the dynamics they learn to create through varying the touch are not enough, or that guitars are incapable of playing slow, serious music. There will always be exceptions to the basic principles to create variety and character.

FULL-VOICE ACCOMPANIMENT

Finally, it must also be remembered that the first half of the seventeenth century was a time of transition into the constant use of basso continuo we associate with the early eighteenth century, and thus often with “Baroque music” in general. Composers (such as Schütz) did not always favor its use, in some works including continuo parts only at the behest of their publishers in order to appear à la mode, and many of the continuo theorists who wrote the manuals from which we derive our knowledge of continuo practice and style also advocated writing out accompaniments exactly from the score—starting with Viadana himself.58 If the vocal counterpoint is reproduced exactly, the composer's carefully constructed voice leading is preserved and the piece is not subject to unexpected and sloppy-sounding collisions between accompanist and singers, the intentional use of such dissonance in the service of affect notwithstanding. Organists especially should be aware of this when deciding how and whether to accompany sacred music from the period and should consult the very useful review of the situation by Gregory Johnston.59

REVIEW OF SOURCES

Continuo treatises are not of the greatest help when actually playing music, as there is very little that can really prepare one for the sensitive requirements of following a soloist and providing supportive accompaniment while improvising from a given bass line that may or may not have figures. Experience in both playing and watching/listening to others play is the only true teacher here. Although the sources do offer a few comments that are of help, they are at times amusingly contradictory. F. T. Arnold (The Art of Accompaniment from a Thorough-bass [1931, repr. 1965]) and Peter Williams (Figured Bass Accompaniment [1970]) have each organized discussion on the dos and don'ts of stylistic accompaniment with reference to period sources, so it is unnecessary to repeat this advice; readers are encouraged to refer to their work for further information. Instead, the following is a compilation of some seventeenth-century treatises either specifically devoted to or at least including basso continuo instruction, listed chronologically by date of first printing or appearance, with some indication of probable instrument(s) intended.

Lodovico Grossi da Viadana. Cento concerti ecclesiastici. Rome, 1603. Organ.

Agostino Agazzari. Del sonare sopra il basso. Siena, 1607. Many instruments.

Francesco Bianciardi. Breve regolo per imparar a sonare sopra il basso con ogni sorte d'instrumento. Siena, 1607. Many instruments.

Adriano Banchieri. “Dialogo musicale.” Printed in the 2nd ed. of L'organo suonarino. Venice, 1611. Organ.

Michael Praetorius. Syntagma Musicum III. Wolfenbüttel, 1619. He quotes freely, with useful editorial comment, from both Viadana and Agazzari. Many instruments.

Johann Staden. Kurzer und einfältiger Bericht für diejenigen, so im Basso ad Organum unerfahren, was bey demselben zum Theil in Acht zu nehmen (appended to his Kirchenmusik, Ander Theil). Nuremberg, 1626. Organ.

Galeazzo Sabbatini. Regola facile e breve per sonare sopra il basso continuo nell’ organo, manacordo, ò altro simile stromento. Venice, 1628. Organ, harpsichord, “or other similar instrument.”

Heinrich Albert. A set of nine rules without separate title, given in the preface to his Arien, vol. 2. Königsberg, 1640. No instrument specified, but organ, harpsichord, and lute are all mentioned.

Wolfgang Ebner. A set of fifteen rules printed by Johann Andreas Herbst in his Arte prattica et poetica. Frankfurt, 1653. None mentioned, but he was an organist.

Nicolas Fleury. Méthode pour apprendre facilement à toucher le théorbe sur la basse-continué. Paris, 1660. Theorbo.

Lorenzo Penna. Li primi albori musicali per li principianti della musica figurata, libro 2. Bologna, 1672. “Organ or harpsichord” in title, but in the book he mentions only the organ.

Matthew Locke. Melothesia, or Certain Rules for Playing upon a Continued-Bass. London, 1673. Harpsichord, organ.

John Blow. “Rules for Playing of a Through Bass upon Organ & Harpsicon.” London, BL Add. MS 34072; ca. 1674. Organ and harpsichord.

Gaspar Sanz. Instruccion de musica sobre la guitarra española. Zaragoça, 1674. Guitar.

Bartolomeo Bismantova. Compendio musicale. Ms. Ferrara, 1677. Keyboard instrument.

Perrine [first name unknown]. Table pour apprendre à toucher le luth sur la basse continué. Paris, 1682. Lute.

Jean-Henri d'Anglebert. Principes de l'accompagnement, printed in his Pièces de clavecin, vol. 1. Paris, 1689. Harpsichord.

Denis Delair, Traité de l'accompagnement pour le théorbo et la clavessin. Paris, 1690. Theorbo and harpsichord.

Andreas Werckmeister. Die nothwendigsten Anmerckungen und Regeln wie der Bassus continuus oder General-Bass wohl könne tractiret werden. Ascherleben, 1698. Keyboard instrument.

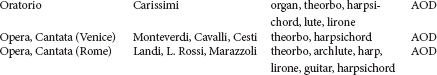

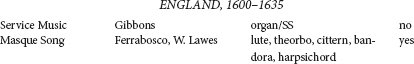

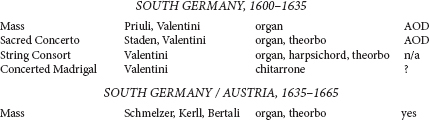

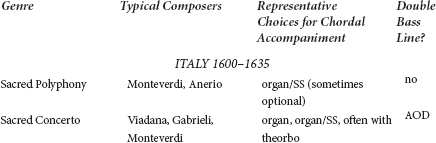

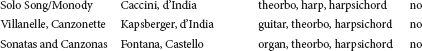

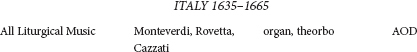

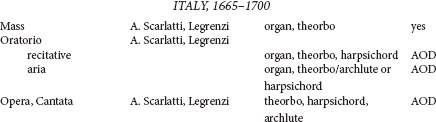

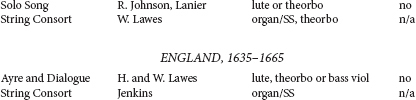

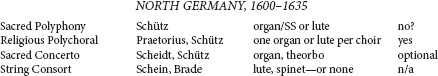

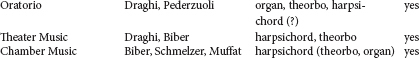

SUMMARY GUIDE TO SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CONTINUO PRACTICE

The chart on the following pages provides a rough overview of continuo practice in seventeenth-century Europe, arranged geographically, chronologically, and by genre. It may be used to amplify and confirm general observations in the text.

In the chordal accompaniment column, we have listed instruments associated with continuo accompaniment for the given repertory, because they are mentioned on title pages, in performance parts, or in descriptions of performances. They represent the best and most probable choices, in rough priority order, generally speaking.

The question of whether to double the bass line rarely lends itself to an unequivocal answer. Where we know period practice with some certainty, the word “no” or “yes” appears in the far right column. Other entries are given best-guess estimates, sometimes with elaboration, based both on recent scholarship and our own intuition. Indeed, one purpose of these explanations is to give a sense of the ambiguity surrounding the topic; players should make informed decisions accordingly.

We have not attempted to specify which instrument should be used for doubling. The choices are manifold, the terminology seldom clear. For example, “violone” can mean a member of the viol family at either eight-foot or sixteen-foot pitch; it was also a synonym for “violoncello” in late seventeenth-century Italy (see the chapter “Violoncello and Violone” by Marc Vanscheeuwijck in this volume; also, Bonta, “From Violone to Violoncello”). Doubling at sixteen-foot pitch was practiced at times (e.g., early seventeenth-century Germany), but it is simply inadvisable to make categorical statements using the terms “always,” “never,” and “sixteen-foot pitch” in the same sentence.

In consort or orchestral textures where all lines including the bass are played by string or wind instruments as a matter of course, this column is marked “n/a,” since the question of doubling is irrelevant.

“SS” in the third column means “short score”–style accompaniment, meaning that the keyboard player (or lutenist) plays the notes the chorus is singing, not an improvisatory realization.

“AOD” in the last column stands for “as occasion demands”; see notes referenced to each.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Our chart represents likely possibilities for continuo instrumentation with evidence to support these possibilities drawn from period title pages and/or surviving parts, of which only a few are detailed here. This cannot guarantee a complete or unified picture, but it is a starting point from which performers can elaborate and refine by working firsthand with original sources. Modern editions are often misleading in matters of instrumentation, as they combine two similar parts into one line, or suggest doublings that are not indicated in the original. For some repertories, one or more secondary sources are especially important in accessing or interpreting this information; these are noted individually, with full entries found in the bibliography for this chapter.

In Viadana's Cento concerti ecclesiastici (1602), the organ is surrogate for a vocal ensemble and should basically double the vocal polyphony or sound like vocal polyphony in its absence; the bass line should not be doubled as a matter of course. Agazzari, however, suggests the participation of a violone in large ensembles and adds that it makes a nice effect when “touching the octave below the bass” from time to time; his instruction is published with sacred music in 1607. Chitarrone, violone, and so on were sometimes included as part of a separate choir in polychoral music; their participation was with that choir and was not necessarily considered as “doubling.” This is seen through mid-century.

Separate bass parts are provided for pieces with independent bass lines.

![]()

An accompanying bowed string on the bass line is used only when other strings are playing; it thus becomes part of a string ensemble. It does not play in a polyphonic vocal texture unless violins are also playing.

![]()

Peri and Cavalieri mention the participation of a “lira grande” (= lirone) in their prefaces. This instrument, because of its unusual tuning, is unable to perform the notated bass line but provides a sustained chordal accompaniment (refer to the remarks under Large Continuo Ensembles above). In Orfeo, Monteverdi specifies a bass bowed string in only three short passages, apart from the five-part string band. All are at turbulent, highly charged emotional points and would seem to be intended for special effect.

Bibliography: Borgir, Performance; Stubbs, L'armonia

In a collection of psalms published in 1660, Cazzati suggests “organs” or, if unavailable, violone, trombone, or some similar instrument (for reference pitch); this does not correspond to “doubling” the line. Also, some polychoral collections designate a part with one of the choirs as “violone o tiorba”; these are not in addition to organ parts for those choirs and do not “double” anything. But doubling does seem to have been standard practice in especially large churches such as San Petronio in Bologna. Otherwise, the bass line cannot be heard with clarity.

Evidence from earlier operatic practice, coupled with indications in oratorio scores of the 1640s and 1650s, suggests that bass lines were occasionally doubled depending on the desired effect. Certainly, it makes more sense to double moving bass lines in arioso sections than those in static recitative passages. Doubling is also less likely in lighter musical textures.

![]()

Bibliography: Borgir, Performance; Murata, Operas; Dixon, “Continuo Scoring”; Mason, Chitarrone

Surviving parts (or lack of them) indicate that small ensembles (one or two solo voices + bc) were not performed with the bass line doubled, while larger groups were.

![]()

An independent part for cello or archlute is provided in most cases.

![]()

Bass-line doubling was becoming more common at this time, but was still optional. Trio sonata collections as late as 1697 still list cello doubling as beneplacito. In sonate da camera of Corelli and others, double the bass line only if it is melodically interesting.

![]()

Bibliography: Allsop, Trio Sonata; Borgir, Performance

Bass lines were probably doubled to make them clearer in large, resonant rooms such as the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall.

Lighter dance music, such as Jenkins's lyra consorts, was often accompanied by a harpsichord doubling the upper parts.

![]()

In anthems and services with string parts, the practice appears to have been to double the bass line only when the upper strings were playing. Holman also notes that bass viols were employed at times to double the bass singers.

![]()

First wording found on title pages of Restoration collections (e.g., Playford's Theatre of Music); second in Purcell's 1698 publication and Blow's of 1700. Note the conjunction “or” in each case.

![]()

Some performance accounts list bass viols with the continuo group, apart from and in addition to the bass member of the string ensemble. Also, some English theatrical producers followed the French practice of including bass-line doubling to accompany singing, but not instrumental pieces (sinfonias, act tunes, dances, etc.).

![]()

The continuo line is considered one of the “parts” in each of Purcell's publications (Sonatas in III Parts; Sonatas in IV Parts) and must be played by a bowed string, but this is not the same as “doubling” it. The 1683 publication (“III parts”) lists “organ and harpsichord” on the title page; that from 1697 (“IV parts”) lists “harpsichord or organ.”

Bibliography: Holman, Fiddlers

Bibliography: Kirchner, Generalbaß

![]()

One set of parts of Schütz's Weihnachtshistorie (1664) shows that—in that performance, anyway—the organ played all the time but the harpsichord accompanied only the Evangelist's recitatives and one other passage; it did not play during the choruses.

The second and third volumes of Schützs Symphoniæ Sacræ (1647 and 1650) include two partbooks for basso continuo, one each for organ and violon, while Hammerschmidt says that a bowed bass at eight- or sixteen-foot pitch may be added if desired. Rosenmüller's bass parts follow the Italian practice of doubling the bass only as a part of a string consort, not during vocal solo passages.

![]()

Bibliography: Kirchner, Generalbaß

![]()

Continuo lines were doubled at eight' and sixteen' as necessitated by the acoustics.

![]()

Bibliography: Kirchner, Generalbaß; Snyder, Buxtehude

The rubric “organ and violone” seems standard in this repertory.

![]()

No detailed account of the 1662 performance of Il pomo d'oro remains. Guido Adler quotes a 1662 Florentine account of a Cesti serenata, for which continuo was provided by a “grossen Spinet (mit zwei Registern), von der Theorbe und dem Contrabass…die vollstimmigen Chöre sollen ausserdem noch einer Bassviola und dem kleinen Spinett begleitet werden” (Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich 6: xxiv). It is unclear what difference is intended between Contrabass and Bassviola in this context. This account does not indicate whether the bowed instruments played throughout; it is unlikely they did at this early date. The operas of Steffani in the early eighteenth century, for example, do not include bass-line doubling when the archlute plays.

![]()

Schmelzer's instrumental pieces, which include bass with strings, specify organ continuo

![]()

Biber's scores (as well as those of other German composers) often specify fagotto on the continuo line.

Manuscript sources of this repertory sometimes include as many as four copies of the continuo part, suggesting participation by a varied and colorful ensemble.

France, 1600–1635: no basso continuo repertory

Prints with basso continuo do not appear in France until Constantijn Huygens's Pathodia Sacra et Profana (1647), followed by Henri du Mont's Cantica sacra of 1652. However, accounts of performances with lutes and theorbos from the 1610s and later suggest that the practice was not unknown in France in the early part of the century.

Bass violins were the bottom of the five-part string ensemble “house band,” but viols were used to double the bass line in vocal sections, both solo and choral.

![]()

Bibliography: Eppelsheim, Orchester; J. Sadie, Bass Viol; Sadler, Role

![]()

Bibliography: Stein, Songs

NOTES

1. Strunk, Source Readings: 364.

2. See Paras, Music.

3. Worsthorne, Venetian: 98; cited in Mason, Chitarrone: 116.

4. Kite-Powell, “Notation.”

5. Borgir, Performance; Dixon, “Continuo”; O'Dette, “Continuo.”

6. See Dixon, “Continuo.”

7. See Rose, “Agazzari.” An English and German translation, along with a transliteration of the original Italian text, may be accessed at: http://icking-music-archive.org/scores/agazzari/delsonare.pdf. Included is a letter written by Agazzari found as an appendix in Adrian Banchieri's Conclusioni nel suono dell'organo.

8. Tonini, Suonate da chiesa a tre (Venice, 1697): preface.

9. Bianciardi, Breve regola (1607); A. Scarlatti, London, British Library Add MS 14244; B. Pasquini; Bologna, Biblioteca G. B. Martini MS D138 [ii].

10. Locke, Anthems and Motets: xviii.

11. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 899.

12. Bacilly, Remarques, trans. Caswell: 11.

13. Bianciardi, Breve regole (1607); Puliaschi, Musiche (1618): preface.

14. These four sources cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 70, 99, 131, and 153, respectively.

15. Kirchner, Generalbaß: 30.

16. Ibid.

17. Schütz, Psalmen: preface, xii.

18. Praetorius, Syntagma III: 138–139; Praetorius/Kite-Powell, Syntagma III: 144–145.

19. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 15.

20. Agazzari, 1607, cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 70; Bianciardi, 1607, cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 78.

21. Piccinini, Intavolatura: preface.

22. Caccini, Nuove musiche, cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 42–43.

23. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 154, and Tagliavini, “Art”: 299–308.

24. Simpson, Division Viol: 9.

25. Penna, Li primi albori: 186–187; cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 146–147n41.

26. See de Goede, “From Dissonance.”

27. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 70.

28. Cited in ibid.: 148.

29. Cited in ibid.: 109.

30. Cited in ibid.: 210.

31. See Mortensen, “Unerringly Tasteful.”

32. Christensen, Generalbaß-praxis: 39–88.

33. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 170.

34. Cited in ibid.: 69.

35. Cited in ibid.: 156.

36. Cited in ibid.: 228.

37. Cited in ibid.: 136.

38. Cited in ibid.: 18.

39. Cited in ibid.: 157.

40. Cited in ibid.: 207.

41. Cited in ibid.: 70, 72.

42. Cited in ibid.: 70.

43. Cited in Williams, Figured Bass 1: 30.

44. Gasparini, L'armonico pratico: 104–110 (90–94 of trans.).

45. See Caffagni, “Modena”: 25–42.

46. Cited in Kirchner, Generalbaß: 33. See also Praetorius/Kite-Powell, Syntagma Musicum III: 134–151, esp. 145.

47. Cited in Williams, Figured Bass 1: 63.

48. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 153.

49. Penna, Li primi albori: 152–181, cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 138–146.

50. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 129.

51. Cited in ibid.: 150.

52. Bismantova, Compendio: [83]–[84].

53. Cited in Arnold, Thoroughbass: 14.

54. Cited in Kirchner, Generalbaß: 129.

55. Arnold, Thoroughbass: 115–120.

56. Ibid.: 72 and 148, respectively.

57. Borgir, Performance: 141–147.

58. See Arnold, Thoroughbass: 15; see also Praetorius/Kite-Powell, Syntagma Musicum III: 135.

59. Johnston, “Polyphonic Keyboard.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SECONDARY SOURCES

Allsop, “Role”; Allsop, “Trio” Sonata; Arnold, Thoroughbass; Ashworth, “Continuo Realization”; Bonta, “Sacred Music”; Bonta, “Violone to Violoncello”; Borgir, Performance; Burnett, “Bowed String”; Christensen, “Generalbass-Praxis”; de Goede, “From Dissonance”; Dixon, Continuo; Eppelsheim, Orchester; Fortune, “Continuo Instruments”; Fortune, “Italian Secular Song”; Garnsey, “Hand-Plucked”; Gasparini, L'armonico pratico; Goldschmidt, “Instrument-Begleitung”; Hancock, “General Rules”; Hansell, “Orchestral Practice”; Heering, Regeln; Hill, “Realized Continuo”; Holman, “Continuo Realizations”; Holman, Fiddlers; Jander, “Concerto Grosso”; Johnston, “Polyphonic Keyboard”; E. H. Jones, English Song; E. H. Jones, “To Sing and Play”; Kinkeldey, Orgel und Klavier; Kirchner, Generalbaß; Kite-Powell, Renaissance; Kite-Powell, “Notation”; Locke, Anthems and Motets; Mason, Chitarrone; Mortensen, “Unerringly Tasteful”; Murata, Papal Court; Nuti, Performance; O'Dette, Continuo; North, Continuo Playing; Paras. Music; Rose, “Agazzari”; Sadie, Bass Viol; Sadler, “Keyboard Continuo”; Schneider, Anfänge; Schütz, Psalmen Davids; Schnoebelen, “Performance Practices at San Petronio”; Schünemann, “Hertel”; Simpson, Division-Viol; Snyder, Buxtehude; Stein, Songs; Strizich, “Chitarra barocca”; Strunk, Source Readings; Stubbs, L'armonia; Tagliavini, “Art”; Walker, German Sacred; Williams, “Basso Continuo”; Williams, Continuo (New Grove); Williams, Figured Bass; Wilson, Roger North.