![]()

Meter and Tempo

We call the musical style of the seventeenth century “Baroque” in order to acknowledge the extravagant, glorious, sometimes even bizarre quality of this brilliant and emotional music. Innovations in the notation of seventeenth-century music gradually changed Renaissance mensural notation to accommodate this expressive and dramatic style. Three significant aspects of mensural notation changed: (1) the tactus, a down-and-up gesture of the hand to which note values were tied, was increasingly described as having various speeds, and over the course of the seventeenth century it encompassed a longer period of time and became what we call the measure; (2) note values smaller than those included in the mensural system were commonly used; (3) the proportions of mensural notation were still written in the course of a composition to change the relationship of notes to the tactus, but they also began to be freestanding signs, placed at the beginning of the composition and therefore not directly related to a normative tactus or note duration. Time signatures evolved from these but indicate instead what notes are to be included in a measure or bar.

This discussion of seventeenth-century notation will center on that used for most genres of instrumental and vocal music: motets, Masses, madrigals, fantasias, sonatas, concertos, arias, and songs. In addition, three important genres of seventeenth-century music—dramatic recitative, compositions imitating improvisation, and dance music—required performers to interpret the notation of meter and tempo quite differently.1

Of these three genres, the first and most characteristic of a new style in the Baroque was the performance and notation of the recitative. this style, basic to the new opera, was sometimes called recitar cantando or stile rappresentativo. The notation uses the sign![]() and more or less requires the performer today to think of a beat equal to the quarter note, since the singer's part is written using half, quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes while the bass mainly sustains whole notes, except at cadences when the harmony moves faster. Despite notation that seems mathematically correct, descriptions of performance stress that the singer must disregard precise notation in favor of declaiming the text in music according to the cadence and sense of the words. Because of the usefulness and popularity of dramatic declamation in opera, the recitative style was transplanted to other genres, including sacred music and even instrumental music, where the performer would strive to give the effect of declamation in a free and emphatic delivery. The notation of Claudio Monteverdi's Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda is a characteristic example of recitar cantando.

and more or less requires the performer today to think of a beat equal to the quarter note, since the singer's part is written using half, quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes while the bass mainly sustains whole notes, except at cadences when the harmony moves faster. Despite notation that seems mathematically correct, descriptions of performance stress that the singer must disregard precise notation in favor of declaiming the text in music according to the cadence and sense of the words. Because of the usefulness and popularity of dramatic declamation in opera, the recitative style was transplanted to other genres, including sacred music and even instrumental music, where the performer would strive to give the effect of declamation in a free and emphatic delivery. The notation of Claudio Monteverdi's Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda is a characteristic example of recitar cantando.

Dance music, from the early seventeenth-century collection in Michael Praetorius's Terpsichore (1612), through Italian and French collections of dances, culminating in the dances of Jean-Baptiste Lully, Marin Marais, and Louis Couperin near the end of the century, used the usual mensuration and meter signs of the period, with whatever tempo indications are found in lyrical music, but the performer was also guided by the dance itself, through knowing its tempo and metrical structure.

Compositions imitating improvisation were characteristic of much solo music for instruments, mainly as versions of preludes that might have titles such as toccata, intonazione, intrada, and præambulum, among many other names. The French devised a special notation for their préludes non mesurés, using whole notes throughout, to avoid specifying duration or metrical structure, which was left entirely up to the performer. The notation used for other improvisational imitations was usually “correct” in regard to its mathematical accuracy on the page but was supplemented with verbal directions to interpret the notation freely in general as well as in specific instances. The genre itself became well enough known that freedom in performance, called stylus phantasticus by German writers, could be applied almost by rule to appropriate compositions.2

To turn to the mainstream of notation in the seventeenth century, let us first examine the historical notation from which it evolved.

INTRODUCTION TO MENSURAL NOTATION

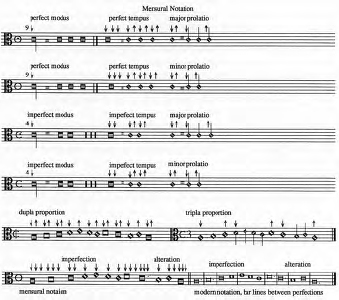

In the early seventeenth century (i.e., in the music of Monteverdi and Praetorius) and in the practice of some musicians well into the late seventeenth century (for instance, Marc-Antoine Charpentier), we find mostly a continuation of sixteenth-century mensural notation, a brief summary of which must suffice here; the interested reader may wish to consult more complete studies.3 In the late fifteenth century, treatises by Franchinus Gaffurius4 and Johannes Tinctoris5 described and reformed mensural notation practices that remained influential during the sixteenth century, although then as now, notation continued to evolve. The mensural notation system was similar to written language in having ambiguities and duplications of meaning that required the reader to consider the context in order to interpret the signs correctly.

In early sixteenth-century practice, the principal note values of mensural notation—the longa, breve, and semibreve—were divided in half or in thirds to make smaller notes. The term modus governed the subdivision of the longa—if perfect, into three breves; if imperfect, into two. Tempus governed the subdivision of the breve into three or two semibreves, and prolatio, major or minor, divided semibreves into three or two minims. A perfect breve was equal to three semibreves, and a perfect semibreve to three minims. In American English, these names have changed: a breve is now a “double whole note,” a semibreve is a “whole note,” and a minim is a “half note.”

The term “perfection” designated three equal units that in total corresponded to the next-larger note value in both tempus and prolatio. If a single breve was notated, it was equal to three semibreves. However, if a breve and a semibreve comprised the “perfection,” the breve was “imperfected” by the semibreve and thus equaled only two semibreves, with the remaining one-third of the perfection made up by the semibreve. Another change in the duration of a note was caused by alteration. If a perfection had only two semibreves, the second one was altered and became twice as long so as to make up the three-thirds of the perfection. Both imperfection and alteration of note values became less frequent in the notation of the seventeenth century.

Example 18.1. Mensural notation

The performer was responsible for recognizing units equal to a “perfection,” aided by rules (for instance, similis ante similem perfecta est—a note followed by its like is perfect) valid at various levels of note values. Where there might be doubt, a “dot of division” would be placed after the note value that completed the perfection to keep it from being reduced one-third in duration or to ensure the alteration of the second semibreve. A device adopted to enforce the reduction of note values by one-third was to fill in, or blacken, the note heads to be imperfected. If the notes were perfect, blackening them made them imperfect; if they were imperfect, blackening made them into “triplets.”

The old sign for tempus perfectum was a circle, and for tempus imperfectum a half circle; prolatio major was indicated by a dot placed inside the circle or half circle, and prolatio minor by no dot. The speed of the various note values was normally linked to the human pulse by the down-and-up gesture of the tactus, the duration of which was equal to the semibreve.

Signs at the beginning of a part indicated whether tempus and prolation were perfect or imperfect, major or minor. this allowed notes that looked exactly alike to be either duple or triple subdivisions of the next larger note. The modus could be indicated by combinations of rests but was usually of no practical significance to sixteenth-century musicians and even less to those of the seventeenth century.

Note values smaller than the minim (half note) always divided the next-larger note by two, unless their appearance was altered by adding a dot of augmentation. In other words, what we recognize as quarter notes, eighth notes, sixteenths, and even smaller notes were always just half of the next-larger note value. They invariably indicated fast notes and were used to write ornamentation examples for learners in method books, and also when composers wished to specify ornamentation within their compositions.

In addition to these signs, mensural notation included proportions: mathematical fractions such as ![]() ,

,![]() and

and ![]() that were placed after the mensuration sign at the beginning or where they were needed in the composition to change the meter, tempo, or both. Proportions changed the relation of notes to the tactus.

that were placed after the mensuration sign at the beginning or where they were needed in the composition to change the meter, tempo, or both. Proportions changed the relation of notes to the tactus. ![]() indicates that two of the same notes replace one,

indicates that two of the same notes replace one, ![]() indicates that three replace one, and

indicates that three replace one, and ![]() means that three of the following equal two of the preceding. Duple proportion was more usually indicated by a vertical slash through the mensuration sign:

means that three of the following equal two of the preceding. Duple proportion was more usually indicated by a vertical slash through the mensuration sign: ![]() was changed to

was changed to ![]() instead of using the fraction

instead of using the fraction ![]() .

.

Both ![]() and

and ![]() indicated the same duple mensural subdivision on all levels of notation and were used interchangeably at the beginning of a composition. However, interpretations of proportions differed and led to confusion. If

indicated the same duple mensural subdivision on all levels of notation and were used interchangeably at the beginning of a composition. However, interpretations of proportions differed and led to confusion. If ![]() in one voice were contrasted simultaneously with

in one voice were contrasted simultaneously with ![]() in another voice, the proportion was required to be exactly

in another voice, the proportion was required to be exactly ![]() ; under

; under ![]() the same notes would move twice as fast as under

the same notes would move twice as fast as under ![]() . In some instances,

. In some instances, ![]() and

and ![]() were not intended to signify a difference of speed but reflected the genre of the composition. Some theorists defined

were not intended to signify a difference of speed but reflected the genre of the composition. Some theorists defined ![]() as one and a half times faster than

as one and a half times faster than ![]() rather than twice as fast, thereby introducing another uncertainty for performers.

rather than twice as fast, thereby introducing another uncertainty for performers.

Tempo was regulated with a steady gesture, called the tactus, usually given by one of the singers with a down-and-up motion of the hand. The tactus was considered to be equal to a person's resting pulse, and therefore generally moderately slow. The duration of the tactus was measured from the bottom of one downstroke to the bottom of the next and normally was equal to the semibreve, our whole note. Breves were equal to two tactus in imperfect tempus, and minims were equal to one half of the tactus in minor prolation. The tactus could be indicated by an equal down-and-up motion for all duple meters, or by a downstroke twice as long as the upstroke for triple meters.

Proportion signs could theoretically indicate tempo changes of almost infinite complexity, but only three proportions were commonly used: ![]() (dupla),

(dupla), ![]() (tripla), and

(tripla), and ![]() (sesquialtera). After a change made by a proportion sign, a change back to the original relation of notes to the tactus could be indicated by the original mensuration sign or by reversing the numbers of the proportion fraction.

(sesquialtera). After a change made by a proportion sign, a change back to the original relation of notes to the tactus could be indicated by the original mensuration sign or by reversing the numbers of the proportion fraction.

Theoretically—or rather, pedagogically—the tactus was an unchanging beat, and consequently the note values proceeded (usually) faster in relation to the tactus by the proportion indicated. A proportion could bring a sharp tempo change, which a present-day musician might think would be the main goal of such notation, but this was sometimes not the case. Changes in note values often accompanied proportions, with the result that tempo changes were altered or even negated. For example, the proportion 2:1 made the breve equal to the tactus instead of the semibreve, but if the note values were doubled in size, only the appearance of the notation would change, not the tempo. This might signal a stylistic change or change of genre to a performer rather than a change of tempo.

Triple proportions often were reduced to a single number 3. The performer must rely on the context of the music to know whether this indicates tripla ![]() or sesquialtera

or sesquialtera ![]() . If the music becomes unreasonably fast by supposing a tripla proportion, or too slow by supposing a sesquialtera proportion, the performer must adjust. Different signs could indicate the same proportion; for instance

. If the music becomes unreasonably fast by supposing a tripla proportion, or too slow by supposing a sesquialtera proportion, the performer must adjust. Different signs could indicate the same proportion; for instance ![]() is the same as

is the same as ![]() .

.

As far as was possible, the older notation was maintained by many seventeenth-century theorists and musicians writing conservative compositions. Monteverdi's notation for the Mass and Vespers of 1610, for instance, is old-fashioned and suitable for the seriousness of sacred vocal music. For the notation to be read correctly, performers had to follow the mensural conventions quite closely and judge tempos by proportions in relation to the tactus. Editions that make changes in the notation to make it more easily read should still make it possible to reconstruct the original note values, tempos, and proportions so that the performer is aware of these aids to interpretation.

MENSURAL NOTATION OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

The Tactus and the Beat

There are some important differences between our idea of the beat in music and the tactus of the early seventeenth century. Both are “beats,” in the sense that the hand (or foot) can fall and rise to indicate a period of time that is equal to the duration of a note, but the tactus was taught to students as an unvarying pulsation against which note values could be performed: notes of large size were slow, and smaller notes were faster, which served to give variety of tempo. The tactus was normally equal to the semibreve, our whole note, but its relationship to notes could be altered by mathematical proportions, indicating, for instance, that two notes be should performed in the time of one, or three in the time of two.

Our “beat” is entirely variable, and although it is usually identified with the quarter note, it can be equated with the half note or eighth note (or dotted half, dotted quarter, dotted eighth, or other note value) by the time signature. Then, with the help of a multitude of tempo words, the performer forms a concept of how fast the beat is. The musical measure is another modern concept, signifying a group of beats to be performed in a manner to distinguish a hierarchical relationship among them, often described as “accented” and “unaccented.”

The conductor of the tactus presumably was chosen because of an ability to execute a constant, steady, unvarying beat, like a clock. this ideal tactus giver might have been something of a pedagogical myth in the early seventeenth century, but the image was retained, along with a normative tempo for the tactus, equal to the resting pulse, or ca. MM = 60. The modern conductor does more than give the beat, of course, but giving the tempo is one of his or her most important functions. My experience is that there are practical limits to how slow or how fast a conductor may beat so as to be followed by an ensemble. If the beat is too slow, the conductor “subdivides,” which doubles the speed of the beat and associates it with the next-smaller note value. If the beat is too fast, then he or she consolidates two beats in one, halves the speed, and associates it with the next-larger note value. In metronome indications, the beat seems to become too slow around MM 40, and too fast around MM 130–135. this provides a range of more than triple the speed of the slowest beat.

A subdivision or consolidation of the conductor's beat was recognized by some seventeenth-century musicians and theorists, such as Andreas Ornithoparcus in John Dowland's translation of 1609:

Of the Division of tact

Tact is threefold, the greater, the lesser, and the proportionate. The greater is a Measure made by a slow, and as it were reciprocall motion. The writers call this tact the whole, or totall tact. And, because it is the true tact of all Songs, it comprehends in his motion a semibreefe not diminished: or a Breefe diminished in a duple.

The lesser Tact, is the half of the greater, which they call a Semitact. Because it measures by it [sic] motion a Semibreefe, diminished in a duple: this is allowed onely by the Unlearned.

The Proportionate is that, whereby three Semibreefes are uttered against one, (as in a Triple) or against two, as in a Sesquialtera.6

I believe that the choice between them depended upon which note value was more conveniently associated with the tactus in performance. Generally, notation using mainly large note values such as the breve (double whole note), semibreve (whole note) and minim (half note)—Praetorius's “motet style”—suggests the tactus maior, equal to the breve. Notation using smaller note values, including half notes, quarter notes, eighths, and sixteenths—“canzona style”—suggests the tactus minor.7

The Speed of the Tactus in the Seventeenth Century

Recognizing the notational difference between motet style and canzona style gives rise to a seeming paradox in the speed of the tactus: when performing motet-style notation with mainly breves (double whole notes) and whole, half, and quarter notes, the tactus (equal to the breve) generally was faster in order that these notes not proceed at a deadly slow pace; and in the canzona style, with half, quarter, eighth and sixteenth notes, the tactus (equal to the whole note) was slower so as not to rush the fast notes.

Other variations of tempo come from a performer's reaction to the meaning of the text. Marin Mersenne's 1636 discussion of the tactus advocates a normative speed, about MM = 60, but he tells us that the ordinary practice of performers varied the speed and the way of indicating the beat, “to suit the custom of singing masters to beat the measure at whatever speed they wish.” Mersenne discussed how the speed of the tactus was frequently quickened or slowed “following the characters, words, or the various emotions they evoke.”8

Two seventeenth-century treatises by Agostino Pisa9 and Pier Francesco Valentini10 are entirely devoted to the tactus and suggest by implication that its normative speed was slower. The seventeenth-century tactus requires minute investigation, because it so often included many small notes which necessarily slow it down. However, Valentini describes a battuta veloce, a “fast beat,” as well as a battuta larga, a “slow beat,” indicating that the tactus had become quite variable. Although neither Pisa nor Valentini specifically states that the normative tactus is slower than before, this might be deduced from the meticulous precision of their description of how to beat the tactus. Both writers describe the tactus gesture as beginning with the descent of the hand, rather than beginning at the bottom of the stroke, which, as Margaret Murata has seen, dissociates the tactus stroke from metrical accentuation. It is very hard to accent the beginning of the descent of the hand.11

Adriano Banchieri also wrote about the tactus,

diverse opinions are in print in volumes, folios, and discourses, some of which maintain that the Battuta begins with the falling of the hand and ends with its ascent; others maintain that it begins on the beat, and terminates on the upstroke; and others say that the motions are sung, and others that the stops [are sung, that is that one sings only when the hand moves or when the hand has come to a stop]. I have observed all these caprices, and I honor them all, leaving to everyone his own opinion. However, I also admire the virtuosi [i.e. the performers], with their fine grace; and forasmuch as actual practice has made it clear to me, I will say briefly that the musical Battuta has several actions, and wishing to describe it, it seems best to divide it into two motions and two stops; the motions we will call descending and ascending, and the stops the downbeat and the upbeat…

Banchieri's examples show that he thinks the tactus begins on the downbeat.12 Does this also suggest that stress or accent may be associated with the gesture?

John Playford and Christopher Simpson in the mid-seventeenth century describe the “measure of the tactus” to musical beginners as quite slow:

To which I answer (in case you have none to guide your Hand at the first measuring of Notes) I would have you pronounce these words (one, two, three, four) in an equal length, as you would (leisurely) read them: Then fancy those four words to be four Crotchets, which make up the quantity or length of a Semibreve, and consequently of a Time or Measure: In which, let these two words (One, Two) be pronounced with the Hand Down; and (Three, Four) with it up.13

Other descriptions of notation link the speed of the tactus to the size of notes used, to the mensuration signs, to proportion signs, or combinations of these in notation. Over the entire century, there seems to be no question that the tactus came to indicate a longer and longer span of time.

Theorists in this instance were reacting to changes that had already taken place in notation and performance, illustrated by compositions in Wilhelm Joseph Wasielewski's excellent Anthology of Instrumental Music from the End of the Sixteenth to the End of the Seventeenth Century, which faithfully reproduces the notation of the original sources.14 Compositions from the early seventeenth century written in the mensuration sign ![]() can be guided by a tactus equal to the whole note: Canzonas La Capriola and No. 2 by Florentio Maschera (pp. 1 and 2), Sonata con tre Violini by Giovanni Gabrieli (p. 13), and even the Canzon à tre by Tarquinio Merula (1639, p. 29) would possibly work with a whole-note tactus. The compositions early in the century written in

can be guided by a tactus equal to the whole note: Canzonas La Capriola and No. 2 by Florentio Maschera (pp. 1 and 2), Sonata con tre Violini by Giovanni Gabrieli (p. 13), and even the Canzon à tre by Tarquinio Merula (1639, p. 29) would possibly work with a whole-note tactus. The compositions early in the century written in ![]() seem reliably to work with a tactus equal to the double whole note: Canzon per sonar, primi toni (p. 4) and the Sonata pian’ e forte by Giovanni Gabrieli (p. 7). The Sonata by Massimiliano Neri (1651, p. 34) has more contrasting note values as well as tempo words (Adagio, Allegro, piú Presto) to indicate tempo changes and quite possibly a slower tactus, perhaps even a subdivided beat equal to the half note. Another composition from the same composer in the same year on page 38 requires a quarter-note beat, as does the Sonata for Violin and Bass by Biagio Marini (1655, p. 40). Most of the later compositions written in

seem reliably to work with a tactus equal to the double whole note: Canzon per sonar, primi toni (p. 4) and the Sonata pian’ e forte by Giovanni Gabrieli (p. 7). The Sonata by Massimiliano Neri (1651, p. 34) has more contrasting note values as well as tempo words (Adagio, Allegro, piú Presto) to indicate tempo changes and quite possibly a slower tactus, perhaps even a subdivided beat equal to the half note. Another composition from the same composer in the same year on page 38 requires a quarter-note beat, as does the Sonata for Violin and Bass by Biagio Marini (1655, p. 40). Most of the later compositions written in ![]() in the collection require four quarter-note beats per bar: Giovanni Legrenzi (1655, 1663, pp. 42–43), Giovanni Battista Vitali (1667, 1668, pp. 47 and 49), Giovanni Battista Mazzaferrata (1674, p. 53), and so on.

in the collection require four quarter-note beats per bar: Giovanni Legrenzi (1655, 1663, pp. 42–43), Giovanni Battista Vitali (1667, 1668, pp. 47 and 49), Giovanni Battista Mazzaferrata (1674, p. 53), and so on.

The gradually increasing use of tempo words through the century is also striking in the anthology, as is the number of compositions written with modern triple time signatures, which will be discussed later in this essay.

Notation using a tactus sometimes subordinates the perceptible metrical structure of the music to metrically neutral notation in order to clarify tempo relationships. Biagio Marini's Romanesca per violino solo e basso (1620, p. 18) is a prime example, in which the triple meter of the composition is written in ![]() through four partes. The reason for this seemingly obtuse notation is that the tactus implied no metrical structure through accentuation, unlike our concept of the beat and the measure, but it was taken as a reliable guide to tempo. The tempos of the subsequent gagliarda and corente are suggested through proportions and the durations of larger and smaller notes.

through four partes. The reason for this seemingly obtuse notation is that the tactus implied no metrical structure through accentuation, unlike our concept of the beat and the measure, but it was taken as a reliable guide to tempo. The tempos of the subsequent gagliarda and corente are suggested through proportions and the durations of larger and smaller notes.

SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MENSURATION AND PROPORTION SIGNS

Duple Meter Signs

The common, almost ubiquitous signs used to designate duple meters in the early seventeenth century are visually familiar to performers today: ![]() and

and ![]() , which we call “common time” and equate with a quarter-note beat, four to the measure; and alla breve or “cut time,” thought to indicate a half-note beat, two to the measure. Banchieri's Cartella musica of 1614 tells us how musicians interpreted

, which we call “common time” and equate with a quarter-note beat, four to the measure; and alla breve or “cut time,” thought to indicate a half-note beat, two to the measure. Banchieri's Cartella musica of 1614 tells us how musicians interpreted ![]() and

and ![]() in the seventeenth century:

in the seventeenth century:

It is true that nowadays, by means of a misuse converted into a [common] usage, both [tempi] have come to be executed in the same way, [by] singing and resting according to the value of the semibreve, and beating the Major Perfect [![]() ] fast [presto] (since it has white notes) and the Minor Perfect [

] fast [presto] (since it has white notes) and the Minor Perfect [![]() ] slow [adagio], since it has black notes. The one and the other turn out [to be] the same, except that there is a difference between the two in the proportions of equality, in sesquialtera of inequality, tripla and hemiolia.15

] slow [adagio], since it has black notes. The one and the other turn out [to be] the same, except that there is a difference between the two in the proportions of equality, in sesquialtera of inequality, tripla and hemiolia.15

Michael Praetorius's Syntagma Musicum III gives more details of this change as well as other changes in the practical use of mensural notation. His was an influential treatise for seventeenth-century musicians and is a valuable guide to us today, particularly for showing how much mensuration and proportion signs need the context of genre and style for a proper interpretation:

At the present time these two signs [![]() and

and ![]() ] are used;

] are used; ![]() usually in madrigals and

usually in madrigals and ![]() in motets. Madrigals and other cantiones that abound in quarters and eighths under the sign

in motets. Madrigals and other cantiones that abound in quarters and eighths under the sign ![]() , move with a faster motion; motets, on the other hand, that abound in breves and semibreves under the sign

, move with a faster motion; motets, on the other hand, that abound in breves and semibreves under the sign ![]() [move with a] slower [motion]; therefore the tactus in the latter is faster, and in the former is slower, by which a mean between two extremes is kept, lest too slow a speed produce displeasure in the ears of the listener, or too fast a speed lead to a precipice, just as the horses of the sun snatched away Phaeton, when the chariot obeyed no reins.

[move with a] slower [motion]; therefore the tactus in the latter is faster, and in the former is slower, by which a mean between two extremes is kept, lest too slow a speed produce displeasure in the ears of the listener, or too fast a speed lead to a precipice, just as the horses of the sun snatched away Phaeton, when the chariot obeyed no reins.

This indicates to me that motets and other sacred music written with many black notes and given the sign ![]() must be performed with a tactus that is somewhat grave and slow. this can be seen in Orlando [di Lasso]'s four-voiced Magnificat and Marenzio's early sacred and other madrigals. Each person can consider these matters for himself and, considering the text and harmony, take the tactus more slowly or more quickly.

must be performed with a tactus that is somewhat grave and slow. this can be seen in Orlando [di Lasso]'s four-voiced Magnificat and Marenzio's early sacred and other madrigals. Each person can consider these matters for himself and, considering the text and harmony, take the tactus more slowly or more quickly.

It is certain, and important to note, that choral concertos must be taken with a slow, grave tactus. Sometimes in such concertos, madrigal and motet styles are found mixed together and alternated, and these must be regulated through conducting the tactus. From this comes an important invention. Sometimes…the Italian words adagio and presto, meaning slow and fast, are written in the parts, since otherwise when the signs ![]() and

and ![]() so often alternate, confusion and problems may arise.16

so often alternate, confusion and problems may arise.16

For Praetorius's contemporaries, the uncertainty of how to interpret this notation was sufficient to initiate the “important invention” of including a verbal description of tempo change. We may interpret from what he writes that the tempo words, the notation signs, and note values indicate an uncertain but moderate acceleration (presto or velociter) or deceleration (adagio or tardè) in the speed of the tactus; only much later do these words indicate extreme variations of tempo.

Étienne Darbellay's investigation of tempo and tactus in the notation of Frescobaldi shows that what Banchieri and Praetorius have written about ![]() and

and ![]() applies to Frescobaldi's music, particularly the Capricci of 1624, with their lively and contrasting tempos.17 Frescobaldi uses only

applies to Frescobaldi's music, particularly the Capricci of 1624, with their lively and contrasting tempos.17 Frescobaldi uses only ![]() as a duple mensuration sign in his Capricci of 1624 but employs note sizes that contrast with one another to mark different styles. For instance, notation using whole, half, and quarter notes can be equated with

as a duple mensuration sign in his Capricci of 1624 but employs note sizes that contrast with one another to mark different styles. For instance, notation using whole, half, and quarter notes can be equated with ![]() , and notation using quarters, eighths, and sixteenths imply

, and notation using quarters, eighths, and sixteenths imply ![]() . Darbellay takes Praetorius's description of the predominant note values of the two genres, madrigal and motet, as one of the major points to be observed in assigning the different tempos of the tactus, using the term Notenbild, or “note picture.” this clarifies an important point for instrumental music, where there is no text to guide one as in the motet or madrigal, but where the note values may be clearly differentiated. In duple meters, seventeenth-century performers read large note values to signify slow music, and small notes fast music, although the tactus would be adjusted so as to avoid the most extreme tempo differences implied by the notation alone.

. Darbellay takes Praetorius's description of the predominant note values of the two genres, madrigal and motet, as one of the major points to be observed in assigning the different tempos of the tactus, using the term Notenbild, or “note picture.” this clarifies an important point for instrumental music, where there is no text to guide one as in the motet or madrigal, but where the note values may be clearly differentiated. In duple meters, seventeenth-century performers read large note values to signify slow music, and small notes fast music, although the tactus would be adjusted so as to avoid the most extreme tempo differences implied by the notation alone.

Triple Meter Signs

Triple meter signs are a good deal more complex than duple signs. For the first time in notational practice, “freestanding” proportional signs, that is, triple proportions that do not refer to a previously established integral value, are frequently found at the beginning of a composition. Sometimes, later in the work, a sign might indicate a value to which the proportion would have been related, had the sign come first, but sometimes the freestanding proportion is the only meter sign. ![]() ,

,![]() , or plain 3 will usually introduce a composition with three half notes to the bar or beat and

, or plain 3 will usually introduce a composition with three half notes to the bar or beat and ![]() ,

, ![]() , or plain 3 will indicate a bar or beat equal to three whole notes. These freestanding signs, which may or may not deserve to be called proportions, are found in place of the now obsolete signs of the semicircle with a dot that indicated major prolation and the circle that indicated tempus perfectum in sixteenth-century mensural notation. The tempo significance of freestanding triple signs may be more subject to a performer's interpretation than true proportions, since they have no relation to a normative duple tactus, but only the suggestion of tempo that note values alone give.

, or plain 3 will indicate a bar or beat equal to three whole notes. These freestanding signs, which may or may not deserve to be called proportions, are found in place of the now obsolete signs of the semicircle with a dot that indicated major prolation and the circle that indicated tempus perfectum in sixteenth-century mensural notation. The tempo significance of freestanding triple signs may be more subject to a performer's interpretation than true proportions, since they have no relation to a normative duple tactus, but only the suggestion of tempo that note values alone give.

Examples of proportio tripla as freestanding signatures are found in Praetorius's Urania of 1613, specifically parts 5 (Surrexit Christus), 8 (Allein Gott), 15 (Erstanden ist der heilge Christ), among other sections of the work. Proportio sesquialtera as a freestanding signature is found in the last three movements of Monteverdi's Vespers of 1610. Praetorius's Musarum Sioniarum Motectœ et Psalmi Latini of 1607 includes as part 34 a “Canticum trium puerorum” of fourteen verses, with alternating verses that have signatures of ![]() and 3, each a separate piece ending with a double bar. Te sections in

and 3, each a separate piece ending with a double bar. Te sections in ![]() use eighth notes as their smallest value, with quarter and half notes predominating, which implies that the tactus is tardior, slower. Te sections in 3 have three whole notes to the tactus, which probably is celerior, faster. Another example is from Lodovico Grossi da Viadana's Concerti ecclesiastici of 1602: Sanctorum Mentis begins with the sign

use eighth notes as their smallest value, with quarter and half notes predominating, which implies that the tactus is tardior, slower. Te sections in 3 have three whole notes to the tactus, which probably is celerior, faster. Another example is from Lodovico Grossi da Viadana's Concerti ecclesiastici of 1602: Sanctorum Mentis begins with the sign ![]() 2 and uses three whole notes to a tactus.

2 and uses three whole notes to a tactus.

The use of triple meters within compositions beginning with ![]() or

or ![]() is very frequent in the first half of the seventeenth century. For these, the proportional meaning of the fractions

is very frequent in the first half of the seventeenth century. For these, the proportional meaning of the fractions ![]() and 2 is exact and refers to the normative tempo of the tactus signified by

and 2 is exact and refers to the normative tempo of the tactus signified by ![]() or

or ![]() , confirmed by the size of notes employed under these signs. One of the most celebrated pieces using these signs and proportions is Monteverdi's Sonata sopra Sancta Maria, included in the Vespers of 1610, which has been thoroughly discussed by Roger Bowers, a scholar of medieval music, in a recent and important article.18 There are seven changes to

, confirmed by the size of notes employed under these signs. One of the most celebrated pieces using these signs and proportions is Monteverdi's Sonata sopra Sancta Maria, included in the Vespers of 1610, which has been thoroughly discussed by Roger Bowers, a scholar of medieval music, in a recent and important article.18 There are seven changes to ![]() from

from ![]() , all sesquialtera proportions that replace a duple tactus equal to a whole note with a tactus equal to three half notes. Of these changes, all are straightforward except the fifth return to

, all sesquialtera proportions that replace a duple tactus equal to a whole note with a tactus equal to three half notes. Of these changes, all are straightforward except the fifth return to ![]() at tactus 130, p. 262 in the Malipiero edition. Monteverdi's notation here, while written in

at tactus 130, p. 262 in the Malipiero edition. Monteverdi's notation here, while written in ![]() , uses blackened minims (filled-in half notes, identical to quarter notes) with the number 3 written above to indicate that there are three to each tactus, half-note triplets, for all parts except for the treble “cantus firmus,” which is notated in longer duple note values. The result of this unusual notation is precisely equal to the proportion of

, uses blackened minims (filled-in half notes, identical to quarter notes) with the number 3 written above to indicate that there are three to each tactus, half-note triplets, for all parts except for the treble “cantus firmus,” which is notated in longer duple note values. The result of this unusual notation is precisely equal to the proportion of ![]() , used in the rest of the composition.

, used in the rest of the composition.

This has been changed in the Malipiero edition by halving the value of the blackened half notes so that they not only look like, but have the value of triplet quarter notes, which also requires halving the value of the simultaneous quite ordinary notation of the cantus firmus that sings a repetition of the ostinato phrase “Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis.” Malipiero's change of Monteverdi's notation has been incorporated into many if not all other modern editions, and Roger Bowers's correction of it has not been accepted by all. There is a question as to why Monteverdi used such unusual old-fashioned notation to indicate the same result as ![]() proportion. Bowers's answer, truly ingenious as well as thoroughly medieval in its reasoning, is that by using this notation Monteverdi contrived a setting comprising an equal number of duple and triple tactus: 147 (this number reflecting the Trinity multiplied by the Seven Joys and the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin). this seems to me not an impossible interpretation, but perhaps one not entirely typical of the thinking of seventeenth-century musicians.

proportion. Bowers's answer, truly ingenious as well as thoroughly medieval in its reasoning, is that by using this notation Monteverdi contrived a setting comprising an equal number of duple and triple tactus: 147 (this number reflecting the Trinity multiplied by the Seven Joys and the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin). this seems to me not an impossible interpretation, but perhaps one not entirely typical of the thinking of seventeenth-century musicians.

Bowers asserts that Monteverdi's notation is medieval, and his view avoids emphasizing the changes that have altered aspects of it to fit the more modern practice of musicians of the early Baroque era. His main point is that this notation is according to mensural principles of long standing and in accord with the theorists of the early seventeenth century.

In Frescobaldi's Capricci of 1624, the first Sopra Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La begins with the sign ![]() with whole, half, and quarter notes, suggesting a tactus celerior equal to the breve. The first proportion (m. 33) with the sign

with whole, half, and quarter notes, suggesting a tactus celerior equal to the breve. The first proportion (m. 33) with the sign ![]() with a dot followed by 3 (

with a dot followed by 3 (![]() 3) equates three half notes to the former whole note—in other words, a

3) equates three half notes to the former whole note—in other words, a ![]() or sesquialtera proportion. The music returns to

or sesquialtera proportion. The music returns to ![]() (m. 48) with some eighth and sixteenth notes as well as half and quarter notes. Perhaps the tactus would be given slightly more slowly. The next proportion is

(m. 48) with some eighth and sixteenth notes as well as half and quarter notes. Perhaps the tactus would be given slightly more slowly. The next proportion is ![]() (measure 77), a tripla proportion with three whole notes to the tactus, which might be given a bit faster. The next

(measure 77), a tripla proportion with three whole notes to the tactus, which might be given a bit faster. The next ![]() (measure 84) has mainly sixteenth notes; consequently, one might use a tactus equal to the whole note, given more slowly. Further changes continue through the 196 measures of the piece.

(measure 84) has mainly sixteenth notes; consequently, one might use a tactus equal to the whole note, given more slowly. Further changes continue through the 196 measures of the piece.

Praetorius gives a thorough exposition of the Signis proportionatis in Tactu Inœquali.19 He states that under triple signs, the large notes are slower and the small notes faster than they would be in a strict proportion. Perhaps the most important element in Praetorius's explanation is that the sign itself signifies the speed of the tactus, although the genre of composition and the size of the notes must also be considered.

Praetorius adds another triple meter, the Sextupla, seu Tactu Trochaico Diminuta,20 measured with an ordinary duple tactus. The term sextupla, Praetorius writes, means that there are six semiminims (quarter notes) in one tactus. These are sometimes written with the number 3 over each group of three notes. The sextupla can be notated in three ways. (1) In hemiolia minore (all black notes under the sign ![]() ), here there are three black minims or semibreve cum minima on the downstroke, and three on the upstroke. If the sign

), here there are three black minims or semibreve cum minima on the downstroke, and three on the upstroke. If the sign ![]() is used for hemiolia minore, it indicates a proportion equating six semiminims or black minims with the tactus. (2) The second sextupla is used by the French and Italians in “Courranten, Sarabanden,” and other similar pieces. Minims and semiminims are used in place of the black semibreves and black minims of the first sextupla. The sign

is used for hemiolia minore, it indicates a proportion equating six semiminims or black minims with the tactus. (2) The second sextupla is used by the French and Italians in “Courranten, Sarabanden,” and other similar pieces. Minims and semiminims are used in place of the black semibreves and black minims of the first sextupla. The sign ![]() indicates that six semiminims equal four of those before the sign. (3) The third way, Praetorius cautions, has proved so difficult for performers that he is uncertain whether it should be used. The sign sesquialtera,

indicates that six semiminims equal four of those before the sign. (3) The third way, Praetorius cautions, has proved so difficult for performers that he is uncertain whether it should be used. The sign sesquialtera, ![]() , is used with semibreves and minims, but the tactus must be taken very fast, which often causes confusion; therefore he has written a retorted

, is used with semibreves and minims, but the tactus must be taken very fast, which often causes confusion; therefore he has written a retorted ![]() before the

before the ![]() proportion to indicate this fast speed. An example of this last notation is found in Praetorius's Puericinium of 1621, no. 4, Singet und klinget, on page 30 of vol. XIX of the Gesamtausgabe. Praetorius is uncertain enough of the performer's familiarity with this to write a considerable preface in the score in explanation, and to mark the music with both presto and celeriter.

proportion to indicate this fast speed. An example of this last notation is found in Praetorius's Puericinium of 1621, no. 4, Singet und klinget, on page 30 of vol. XIX of the Gesamtausgabe. Praetorius is uncertain enough of the performer's familiarity with this to write a considerable preface in the score in explanation, and to mark the music with both presto and celeriter.

Frescobaldi's use of this sextupla (sei per quatro) meter can be seen in Capriccio V, sopra la Bassa Fiamenga, at measure 57, more or less in the first kind of notation described for sextupla by Praetorius.

The relationship of ![]() and

and ![]() to the various kinds of triple proportions, while complex, can be rationally understood in most cases. The relationship is less clear when a triple meter follows a recitative-like section written in

to the various kinds of triple proportions, while complex, can be rationally understood in most cases. The relationship is less clear when a triple meter follows a recitative-like section written in ![]() , which must be performed freely according to the dramatic declamation of the words. Examples of this abound in the cantatas of Barbara Strozzi, for example Cieli, Stelle, Deitadi from her Op. 8. The first of Schütz's Kleine geistliche Konzerte of 1636 begins with a recitative-like section which is labeled stylo oratorio to warn the singer of its declamatory nature. A succeeding triple proportion cannot be calculated on the basis of a reliable steady tactus but perhaps might be regarded as if it were a freestanding metrical sign.

, which must be performed freely according to the dramatic declamation of the words. Examples of this abound in the cantatas of Barbara Strozzi, for example Cieli, Stelle, Deitadi from her Op. 8. The first of Schütz's Kleine geistliche Konzerte of 1636 begins with a recitative-like section which is labeled stylo oratorio to warn the singer of its declamatory nature. A succeeding triple proportion cannot be calculated on the basis of a reliable steady tactus but perhaps might be regarded as if it were a freestanding metrical sign.

At this point in our discussion of seventeenth-century notation, the main principles of the conservative notation still widely used in the first half of the century have been considered.

THE ADVENT OF TIME SIGNATURES

The third major change in notation comes when freestanding triple mensural proportion signs were transformed into the fractional numbers of modern time signatures. Along with the invention and increasing use of these “new signs” used by “the Italians” (according to Jean Rousseau in 1683) comes a recognition that the measure (of the tactus) is no longer the duration of the musical beat, but rather a collection of beats organized by a different perception of meter.

An antique and conservative view of proportions is given by Pier Francesco Valentini in more than 150 pages of a closely written manuscript.21 For Valentini, whatever number and size of notes replace those previous to the proportion, they occupy an equal amount of time. For instance, for him the proportions of ![]() and

and ![]() differ only in the size of the notes used, not in their speed.

differ only in the size of the notes used, not in their speed.

Valentini gives examples of many numerical proportions, both duple and triple, and shows the value of every note in relation to the tactus. Each proportion is preceded by a mensuration sign that allows the performer to know the relationship of notes to the tactus both before and after the proportional change. Valentini explores every possible proportion regardless of its practical use, including superparticular proportions such as ![]() , 76, and

, 76, and ![]() , multiple proportions such as

, multiple proportions such as ![]() and

and ![]() , and submultiple proportions such as

, and submultiple proportions such as ![]() and

and ![]() .22 Among the plethora of fractions cited are those that subsequently became time signatures.

.22 Among the plethora of fractions cited are those that subsequently became time signatures.

One interpretation of proportions is based on the equivalence of notes to one another; in ![]() three of any note value after the sign becomes equivalent to two before it. In

three of any note value after the sign becomes equivalent to two before it. In ![]() , three semibreves become equivalent to two semibreves, and under

, three semibreves become equivalent to two semibreves, and under ![]() , three minims to two minims. In another system, the tactus is the unit of equivalence: in

, three minims to two minims. In another system, the tactus is the unit of equivalence: in ![]() , the note values of three-thirds of a tactus become equivalent to two halves. The results are not altered, but Dahlhaus points out that the second system is closer to establishing the semibreve as the “whole note,” the equivalent of a measure.23

, the note values of three-thirds of a tactus become equivalent to two halves. The results are not altered, but Dahlhaus points out that the second system is closer to establishing the semibreve as the “whole note,” the equivalent of a measure.23

Most theorists continued to hold that the speed of notes was relevant to the normative tactus of ![]() and

and ![]() , the signs governing mensural tempus (tempo in Italian), a word that evolved to mean the speed of notes. Proportion numbers were sometimes used alone, without a mensural sign to specify their relation to the tactus. this was not approved by most conservative theorists during the seventeenth century, including Giovanni Maria Bononcini, who wrote: “finally it must be said that to use the proportions without mensural signs is (as Valerio Bona says in his Regole di musica) like sending soldiers on the field without a captain.”24

, the signs governing mensural tempus (tempo in Italian), a word that evolved to mean the speed of notes. Proportion numbers were sometimes used alone, without a mensural sign to specify their relation to the tactus. this was not approved by most conservative theorists during the seventeenth century, including Giovanni Maria Bononcini, who wrote: “finally it must be said that to use the proportions without mensural signs is (as Valerio Bona says in his Regole di musica) like sending soldiers on the field without a captain.”24

It is in Bononcini's triple meter signatures and those of Lorenzo Penna (without mensural signs) that we begin to recognize the familiar time signatures of modern measures.

According to Bononcini they are:25

tripla maggiore: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() with three semibreves to the tactus, two on the down-stroke, one on the upstroke.

with three semibreves to the tactus, two on the down-stroke, one on the upstroke.

tripla minore: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , with two minims on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

, with two minims on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

![]() , tripla di semiminime.

, tripla di semiminime.

![]() , tripla di crome.

, tripla di crome.

![]() , sestupla di semiminime.

, sestupla di semiminime.

![]() , sestuple di crome.

, sestuple di crome.

![]() , dodecupla di crome.

, dodecupla di crome.

![]() , dodecupla di semicrome.

, dodecupla di semicrome.

Penna calls them signs of tripola, not proportions, and they are:26

![]() , tripola maggiore, formerly indicated by

, tripola maggiore, formerly indicated by ![]() , three semibreves to the tactus, two on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

, three semibreves to the tactus, two on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

![]() , tripola minore, formerly indicated by

, tripola minore, formerly indicated by ![]() , three minims to the tactus, two on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

, three minims to the tactus, two on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

![]() , la tripola picciola, ó quadrupla, ó semiminore, ó di semiminime, semiminims and minims, two semiminims on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

, la tripola picciola, ó quadrupla, ó semiminore, ó di semiminime, semiminims and minims, two semiminims on the downstroke, one on the upstroke.

![]() , la tripola crometta,, ó ottina, ó di crome.

, la tripola crometta,, ó ottina, ó di crome.

![]() , la semicrometta.

, la semicrometta.

![]() ,la sestupla maggiore.

,la sestupla maggiore.

![]() , la sestupla minore.

, la sestupla minore.

![]() , la dosdupla.

, la dosdupla.

Meter signatures with six in the numerator indicate three notes on the downstroke and three on the upstroke ; with twelve in the numerator, there are six on the downstroke and six on the upstroke.

The number of signs is small compared to those given by Valentini, but Penna mentions that he is explaining only those most frequently used. Penna includes a few additional proportions, the hemiolia maggiore and minore, that were “formerly used,” and also the proportions ![]() and

and ![]() , included as tripola, leftovers from Valentini's odd mensural proportions. Penna's explanation is brief, but he mentions that there “are others in other forms.” He also explains some traditional uses of a proportional sign, for example, turning it upside-down signifies a return to the notation before the proportion was introduced.

, included as tripola, leftovers from Valentini's odd mensural proportions. Penna's explanation is brief, but he mentions that there “are others in other forms.” He also explains some traditional uses of a proportional sign, for example, turning it upside-down signifies a return to the notation before the proportion was introduced.

Bononcini retains the mensural ![]() as a guide to his new signs. His general explanation of triple signs involves comparing the tactus and the notes before the proportion sign to those after it.

as a guide to his new signs. His general explanation of triple signs involves comparing the tactus and the notes before the proportion sign to those after it.

Of the others indicated, for greater brevity, they follow this general rule: the lower number indicates which note values went or were understood to go to the beat, and the upper number how many notes will go in the future (i.e. after the sign).27

Penna gives no reason for the omission of a mensural sign (tempo) before the numerical proportion in his signatures, but in 1714, Wolfgang Caspar Printz comments on this:

If the music begins with an irrational proportion [![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ] most of the new musicians omit the mensural sign, and use only the numbers that show the proportion. this is not without cause, as the denominator of the indicated proportion already has the ability to show the length of the tactus: therefore the mensural sign is superfluous, unnecessary, and should be abolished.28

] most of the new musicians omit the mensural sign, and use only the numbers that show the proportion. this is not without cause, as the denominator of the indicated proportion already has the ability to show the length of the tactus: therefore the mensural sign is superfluous, unnecessary, and should be abolished.28

Even in 1714, the fractional number of the time signature is explained as a proportion, but the omission of the mensural sign is explained as if it did not affect the proportional interpretation of the signature.

It seems that the proportion sign is still recognized in its traditional meaning by Bononcini, but he has this to say about the beat that regulates the speed of notes according to the various meter signs:

It should be noted that all of the proportions corresponding to an equal beat are given by the same equal beat, and all the proportions of the unequal beat by the identical unequal beat. The motion does not vary except—occasionally—in speed, now an ordinary pace, now slow, and now fast, according to the wish of the composer, for this reason the parts of a composition are given different signs. Under these signs the same beat easily regulates [the music], as may be seen in the works of Frescobaldi and other learned composers, and in my own opera sesta.29

Bononcini does not explain what signs these are, and the first to come to mind today tempo words such as allegro and adagio, may not have been in his mind. Frescobaldi was one of the first to specify that the “proportion” itself indicates the speed of the beat: “In the triplas, or sesquialteras, if they are major let them be played slowly if minor somewhat more quickly if of three semiminims more rapidly if ![]() , move the beat fast.”30

, move the beat fast.”30

Frescobaldi's interpretation of proportion signs is repeated by many performers and writers in the seventeenth century including Bononcini.

Carissimi amplifies this instruction and includes numerical signatures and the genre of the composition as determinants of the tempo. ![]() , for example, is used in “slow compositions and serious works in the Stylo Ecclesiastico,”

, for example, is used in “slow compositions and serious works in the Stylo Ecclesiastico,” ![]() is “used somewhat more briskly than the former, particularly in the serious style, and therefore the beat must be given somewhat faster.”

is “used somewhat more briskly than the former, particularly in the serious style, and therefore the beat must be given somewhat faster.” ![]() “requires a faster beat than the last as this tripla is used mostly in ariettes and happy pieces.”31

“requires a faster beat than the last as this tripla is used mostly in ariettes and happy pieces.”31

Printz formulates a general rule to govern the speed of the tactus as indicated by proportional signatures:

The length of the trochaic beat is indicated by the lower number of the proportion, therefore this rule should be observed: the smaller the lower number of the proportion, the slower the beat; and the larger the number, the faster the beat.32

Étienne Loulié agrees with this formulation.33

Jean Rousseau derives the speed of some of his triple time signatures from individual note values that are equivalent before and after the fractional sign. He first explains that there are six varieties of ordinary signs, that is, ![]() ,

, ![]() , 2,

, 2, ![]() , 3, and

, 3, and ![]() then that there are four more,

then that there are four more, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , that are “new signs used for only a certain time.” Later he mentions the origin of the “new signs” when he states that “the Italians” also used

, that are “new signs used for only a certain time.” Later he mentions the origin of the “new signs” when he states that “the Italians” also used ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , signs that he does not discuss.34 French music of this period that is written in imitation of the Italian style often uses Italian meter signs:

, signs that he does not discuss.34 French music of this period that is written in imitation of the Italian style often uses Italian meter signs:

Under the sign of ![]() (called thus because in place of the four quarter notes of

(called thus because in place of the four quarter notes of ![]() this measure has only three), the beat is given with three strokes, faster than under the triple simple, 3. As the quickness of these strokes makes them difficult to beat, each gesture is made by two unequal strokes, two quarter notes on the down, and one quarter on the up stroke. Under the sign of

this measure has only three), the beat is given with three strokes, faster than under the triple simple, 3. As the quickness of these strokes makes them difficult to beat, each gesture is made by two unequal strokes, two quarter notes on the down, and one quarter on the up stroke. Under the sign of ![]() , there are three eighth notes instead of eight in

, there are three eighth notes instead of eight in ![]() . The beat is given as it is under the sign of

. The beat is given as it is under the sign of ![]() , but much faster.35

, but much faster.35

Jean Rousseau's explanation contradicts the concept that a measure is equated with the tactus; there are a number of beats in a measure, unless the speed is so fast that it is uncomfortable to give a full gesture to each “beat.” He recognizes that the measure and the tactus are now seen to be quite different from each other.

A change in the meaning of the word tact has also occurred in German late in the seventeenth century. Daniel Merck uses it both in its traditional meaning of tactus and in its modern German sense of “measure,” which makes no sense at all unless the two meanings are understood appropriately and supplied by the reader. “Tripla Major wird diser genennet /…in welchem drey gantze Tact erst einen Tact ausmachen.” (“Tripla Major, as it is called,…is when three whole notes make one measure.”)36 Perhaps Merck's meaning was clear to his contemporary readers, but it can now be understood only by using two terms for the word tact.

Two additional signs, 3 (triple simple) and 2 (le binaire) are frequently used in French tablatures to indicate a basic triple or duple metrical organization. 3 was conducted with two downbeats and one up for slow tempos, one downbeat of two pulses and an upbeat of one pulse for faster tempos, or one downbeat (or upbeat) of three pulses for very fast tempos.37

Loulié states that 3 is the same as ![]() , while Rousseau indicates that it is conducted by three quick strokes (trois temps légers), in contrast to

, while Rousseau indicates that it is conducted by three quick strokes (trois temps légers), in contrast to ![]() 3, which is conducted by three slow strokes. Regardless of the time signatures of French notation, the genre of the piece determines the speed of the music. Georg Muffat (writing about French music) remarks that “gigues and canaries need to be played the fastest of all, no matter what the time signature.”38

3, which is conducted by three slow strokes. Regardless of the time signatures of French notation, the genre of the piece determines the speed of the music. Georg Muffat (writing about French music) remarks that “gigues and canaries need to be played the fastest of all, no matter what the time signature.”38

There are still problems in indicating the tempo of music through time signatures. Saint Lambert comments on the liberties taken by musicians contrary to the rules of tempo implied by signatures and gives an example from the practice of the most eminent musician of the day:

Often the same man marks two airs of completely differing tempo with the same time signature, as for example M. de Lully, who has the reprise of the overture to Armide played very fast and the air on page 93 of the same opera played very slowly, even though this air and the reprise of the overture are both marked with the time signature ![]() , and both have six quarter notes per measure distributed in the same way.39

, and both have six quarter notes per measure distributed in the same way.39

Saint Lambert gives a number of other examples of the confusion surrounding the tempo significance of time signatures and comments that “musicians who recognize this drawback often add one of the following words to the time signature of the pieces they compose: Lentement, Gravement, Légèrement, Gayement, Vite, Fort Vite, and the like, in order to compensate for the inability of the time signatures to express their intention.”40

Note values and time signatures often needed the help of tempo words in order to fully transmit the composer's choice of tempo to performers, but these words were still only secondary indications in the late seventeenth century.

Notation of music from the later seventeenth century often seems so much like the music with which we are familiar that only in a few instances are we reminded that it is different. Sometimes editors rewrite the music, and of course they should inform the performer of what has been done. The most frequent changes made are to rebar the original notation, usually shortening what seem like excessively long measures; to substitute modern time signatures, for instance to replace ![]() with

with ![]() ; and to halve the note values—for instance, to replace half notes and

; and to halve the note values—for instance, to replace half notes and ![]() with quarter notes and

with quarter notes and ![]() . Editors of music of the first half of the seventeenth century are more likely to have made these changes, and they are the cause of most of the confusion that can overtake a knowledgeable performer of this repertory. If you have to use a rewritten edition, the best solution is to try to reconstruct the original notation in order to understand what it implied. All good editions make it possible to reconstruct the original notation if changes have been made, and the very best editions reproduce the original notation, with explanations (if they are required) to enable modern performers to solve unfamiliar problems.

. Editors of music of the first half of the seventeenth century are more likely to have made these changes, and they are the cause of most of the confusion that can overtake a knowledgeable performer of this repertory. If you have to use a rewritten edition, the best solution is to try to reconstruct the original notation in order to understand what it implied. All good editions make it possible to reconstruct the original notation if changes have been made, and the very best editions reproduce the original notation, with explanations (if they are required) to enable modern performers to solve unfamiliar problems.

Much of the music of the seventeenth century is of such high quality and strong emotional force that the intuitions of good performers will lead to good performances even if only a full understanding of the notation will allow the music to shine forth as intended.

NOTES

1. In addition, an entirely different kind of notation called tablature was used for several instruments, notably for plucked string instruments such as lute, theorbo, and guitar, for the viola da gamba played as a lyra viol, and for keyboard music. Tablature notation was even invented for the recorder. Most tablature depicts finger position on the instrument rather than musical pitch and conveys technical information to the performer not included in standard notation. this notation is extremely useful to performers on the particular instruments, now as well as then, but cannot usefully be read by anyone else.

2. See the prefaces to Frescobaldi's Toccate e partite d'intavolatura di cimbalo, 1615, 1616, 1628, 1637, in the Gesamtausgabe, vol. III, ed. P. Pidoux. A translation of Frescobaldi's preface is in McClintock, Readings: 133. See also Hogwood, “Frescobaldi.” For French preludes, see Moroney, “Unmeasured Preludes”: 143.

3. Apel, Notation, is still valuable, but no longer available except on the internet; a digital reproduction may be accessed at http://www.scribd.com/doc/47893060/APEL-Willi-•-The-Notation-of-Polyphonic-Music-900-1600-1949-facsimile-on-music-notation. The most recent study is Berger, Mensuration. The articles “Notation” and “Proportions” in New Grove are also useful.

4. Digital reproductions of Gaffurius's treatise Practica musicæ can be accessed at http://imslp.org/wiki/Practica_musicae_(Gaffurius,_Franchinus)

5. Digital reproductions of several of Tinctoris's treatises and information on his life can be accessed at http://www.stoa.org/tinctoris/tinctoris.html

6. Ornithoparcus, Micrologus, lib. 2, ch. 6: 46. A digital reproduction of the treatise may be accessed at http://books.google.com/books?id=iVg8AAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=ornithoparcus+andreaqs&source=bl&ots=8YlzbscAP0&sig=t13KXESoGxbOCIkF2IhU1Q12rFw&hl=en&ei=cr2fTOmxMcXfgeu3YTxCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CCYQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q&f=false. In Ornithoparcus & Dowland, Compendium: 166.

7. See Praetorius/Kite-Powell, Syntagma III: 68ff, esp. footnotes 29 and 32.

8. Mersenne, Harmonie universelle, Livre cinquiesme de la composition, Proposition XI: 324.

9. Pisa, Battuta.

10. Valentini, Trattato: 34. para. 64, and p. 62, para. 129.

11. Murata, “Valentini”: 330.

12. Cranna, Banchieri: 472–473.

13. Simpson, Compendium: 18–19.

14. Wasielewski, Anthology. The first edition was published in 1874, and Da Capo Press, New York, reissued the Anthology in 1973, with notes by John G. Suess.

15. Cranna, Banchieri: 115. A digital reproduction can be accessed at http://imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/e/e6/IMSLP23500-PMLP53564-cartella_musicale_1614.pdf

16. Praetorius, Syntagma III: 50–51. “Jetzigerzeit aber werden diese beyde Signa meistentheils also observiret, daß das ![]() fürnehmlich in Madrigalien, das

fürnehmlich in Madrigalien, das ![]() aber in Motetten gebraucht wird. Quia Madrigalia & aliœ Cantiones, quœ sub signo

aber in Motetten gebraucht wird. Quia Madrigalia & aliœ Cantiones, quœ sub signo ![]() , Semiminimis & Fusis abundant, celeriori progrediuntur motu; Motectœ autem, quœ sub signo

, Semiminimis & Fusis abundant, celeriori progrediuntur motu; Motectœ autem, quœ sub signo ![]() Brevibus & Semibrevibus abundant, tardiori: Ideo hîc celeriori, illic tardiori opus est Tactu, quò medium inter duo extrema servetur, ne tardior Progressus auditorum auribus pariat fastidium, aut celerior in Prœcipitium ducat, veluti Solis equi Phaëtontem abripuerunt, ubi currus nullas audivit habenas.

Brevibus & Semibrevibus abundant, tardiori: Ideo hîc celeriori, illic tardiori opus est Tactu, quò medium inter duo extrema servetur, ne tardior Progressus auditorum auribus pariat fastidium, aut celerior in Prœcipitium ducat, veluti Solis equi Phaëtontem abripuerunt, ubi currus nullas audivit habenas.

“Darvmb deuchtet mich nicht vbel gethan seyn / wenn man die Motecten, vnd andere geistliche Gesänge / welche mit vielen schwarzen Noten gesetzt seyn / mit diesem Signo ![]() zeichnet; anzuzeigen / daß alßdann der tact etwas langsamer vnd gravitetischer müsse gehalten werden: Wie dann Orlandus in seinen Magnificat 4. Vocum vnd Marentius in vorgedachten Spiritualibus vnd andern Madrigalibus solches in acht genommen. Es kan aber ein jeder den Sachen selbsten nachdenken / vnd ex consideratione Textus & Harmoniœ observiren, wo ein langsamer oder geschwinder tact gehalten werden müsse.

zeichnet; anzuzeigen / daß alßdann der tact etwas langsamer vnd gravitetischer müsse gehalten werden: Wie dann Orlandus in seinen Magnificat 4. Vocum vnd Marentius in vorgedachten Spiritualibus vnd andern Madrigalibus solches in acht genommen. Es kan aber ein jeder den Sachen selbsten nachdenken / vnd ex consideratione Textus & Harmoniœ observiren, wo ein langsamer oder geschwinder tact gehalten werden müsse.

“Dann das ist einmal gewis vnd hochnötig / das in Concerten per Choros ein gar langsamer gravitetischer Tact müsse gehalten werden. Weil aber in solchen Concerten bald Madrigalische / bald Motetten Art vnter einander vermenget vnd vmbgewechselt befunden wird / muss man sich auch im Tactiren darnach richten: Darvmb dann gar ein nötig inventum, das bißweilen / (wie drunten im I. Capittel des Dritten Theils) die Vocabula von den Wälschen adagio, presto, h.e. tardè, Velociter, in den Stimmen darbey notiret vnd vnterzeichnet werden / denn es sonsten mit den beyden Signis ![]() vnd

vnd ![]() so offtmals vmbzuwechseln / mehr Confusiones vnd verhinderungen geben vnd erregen möchte.” See also Praetorius/ Kite-Powell, Syntagma III: 69–71. A digital reproduction can be found at http://www.archive.org/stream/SyntagmaMusicumBd.31619/PraetoriusSyntagmaMusicumB3#page/n0/mode/2up and at http://imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/9/91/IMSLP68477-PMLP138176-PraetoriusSyntagmaMusicumB3.pdf.

so offtmals vmbzuwechseln / mehr Confusiones vnd verhinderungen geben vnd erregen möchte.” See also Praetorius/ Kite-Powell, Syntagma III: 69–71. A digital reproduction can be found at http://www.archive.org/stream/SyntagmaMusicumBd.31619/PraetoriusSyntagmaMusicumB3#page/n0/mode/2up and at http://imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/9/91/IMSLP68477-PMLP138176-PraetoriusSyntagmaMusicumB3.pdf.

17. Darbellay, “Tempo Relationships”: 301–326.

18. Bowers, “Reflections”: 347–395. The music is in the Monteverdi Opere, ed. Malipiero, 14: 250–273.

19. Praetorius, Syntagma III: 52–54; see also Praetorius/Kite-Powell, Syntagma III: 71–73.

20. Ibid.: 73–79; in Praetorius/Kite-Powell, Syntagma III: 86–91.

21. Valentini, Trattato: 300–459.

22. this classification of proportions by antique mathematical terminology is explained in Morley, Plaine and Easie, original edition p. 17, vers. 18, and on pp. 127–128 in the modern edition. A digital reproduction can be accessed at http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc86/m1/1/

23. Dahlhaus, “Taktsystems”: 230–236.

24. Bononcini, Musico prattico: 14. “Per ultimo si deue auuertire, che l'introdurre le proporzioni ne i canti, senza segno del Tempo e (come dice Valerio Bona nelle sue Regole di musica) come mettere i soldati in Campo senza Capitano.”

25. Ibid.: 20–23.

26. Penna, Primi albori: 36–40.

27. Bononcini, Musico prattico: 11. “De gli altri poi che seguono, per maggiore brevità si da questo regola generale, che il numero sotto posto denota quante figure andavano, ò s'intende, che andastero alla battuta, & il sopra posto, quante ne vadino per l'avenire.”

28. Printz, Compendium: 16. “Wenn der Gesang mit einer irrationalen Proportion anfängt / lassen die meisten neuen Musici das Signum quantitatis mensuralis weg / und setzen unter die Zahlen / so die Proportion andeuten / allein: und zwar nicht ohne Ursache. Denn weil die untere Zahl der vorgeschriebenen Irrationalen Proportion schon die Krafft hat die Länge des Tactes anzudeuten / so ist das Signum quantitatis mensuralis überflüssig / unnöthig / und also / vermöge…abzuschaffen.”

29. Bononcini, Musico prattico: 17–24. “Si deue auuertire, che tutte le proporzione di battuta eguale, si deuono constituire sotto l'istessa battuta eguale, e tutte le proporzione di battuta ineguale si deuono anch'esse constituire sotto la medesima battuta ineguale, non variandosi altro che alle volte il moto in questa maniera, cioè facendolo hora ordinario, hora adagio; & hora presto, secondo il voler del Compositore; per il che si possono far composizione, nelle quali le parti siano segnate diuersamente, purche i segni possano essere gouernate facilmente da una istesia battuta, come in diuerse Opere de Frescobaldi, e di molt’ altri dotti Compositore si puï vedere, & eziando nella sesta mia opera.”

30. Frescobaldi, Il primi libro de capricci: preface. “E nelle trippole, ò sesquialtere, se saranno maggiori, si portino adagio, se/minori alquâto più allegre, se di tre semiminime, più allegre se saranno sei per quattro si di/aillor tempo con far caminare la battuta allegra.” See also Hammond, Frescobaldi: 226–227.

31. Carissimi, Ars cantandi: 15.

32. Printz, Compendium: ch. 4: 17. “Die Länge des Trochaischen Tactes wird angedeutet durch die untere Zahl der vorgeschriebenen Proportion, davon diese Regul ist Acht zu neh-men: Je kleiner die untere Zahl der Proportion ist / je langsamer soll der Tact geschlagen werden; und je grösser dieselbe Zahl ist / je geschwinder soll der Tact geschlagen werden.”

33. Loulié, Élemens: 29.