2

Boy soldier

Midrand’s office buildings flash past and, ten minutes later, the Voortrekker Monument looms fatefully ahead. I am on my way to Pretoria Central, Classic FM’s volume turned up high. I hum the words of ‘Gabriella’s Song’ from the movie As it is in Heaven, the story of an internationally renowned conductor who was bullied as a youngster at school and later returned to his hometown where he had a Damascene experience. The N1 is clear this early on a Sunday.

I laugh when I think back to how naïve I was during my first visits. My ignorance was probably my saving grace. Once, for example, I wanted to give something to Eugene. I thought of a book, but which book? A prison story? I decided on Shantaram (where the main character spends a long time in an Indian prison), a packet of biltong and two Lindt chocolates. There must have been an angel on my shoulder that day since I passed through both security checkpoints with the gifts undetected.

Eugene had a support network like very few other prisoners; his affairs were in order. Later, I managed to organise six books and six periodicals that he is allowed to receive monthly and for which he needs a letter of approval from the psychiatrist at Pretoria Central. I also saw to the list of people he wished to see in his allotted visiting hours. We spoke about the books he was interested in and I tried as far as possible to fill his wish list. In between I introduced him to some of my favourites: Cormac McCarthy’s epic trilogy (All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing and Cities of the Plain), Peter Høeg’s Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow and the Stieg Larsson trilogy (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl who Played with Fire and The Girl who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest).

Eugene de Kock as a young boy with his brother, Vosloo, also called ‘Vos’.

I wondered how long it would take before he started trusting me. In my view a true discussion involves two-way communication, a give and take of information and energy. After the umpteenth visit I began to think that, locked up in Pretoria Central, Eugene had simply forgotten how to do this. Even after the seventh, eighth visit, a jumble of stories still poured out in an endless stream, about Koevoet, Vlakplaas, events and contacts, people I didn’t know, prison anecdotes – as if his desire to talk was insatiable. While he always told his stories with a twinkle in his eye, he kept the real Eugene carefully hidden.

Then, one Sunday morning, everything changed. ‘Today, you will talk and I will listen,’ he said. I knew then that we had reached a turning point. From that day I could engage in the kind of conversation with him one would expect in ordinary interaction. No more politics, war stories or hidden agendas. Slowly but surely, piece by piece, Eugene began to share his inner self with me.

Getting to this point was extremely difficult for him, he admitted to me much later. Although he did not want to show it, talking about personal matters was foreign to him.

In time, he arranged for me to meet his brother, Vos, and Rita, Vos’s wife, on their plot in Sundra on the East Rand. They would give me more personal background information and I could look through some family photo albums.

‘Turn left at the yellow house with the green roof,’ said Vos when I phoned him. ‘I am at the house next door. I’ll wait at the gate.’

At eleven o’clock on a Wednesday morning, Vos was waiting on the pavement, holding his four-year-old grandson, Alexander, by the hand. ‘Get in, son,’ he said. ‘We’re going to have a drink.’

The likeness between Vos and his brother is remarkable. The characteristic De Kock facial features and disposition struck me time and again during the course of that day. As soon as he got into my car, Vos started talking – as intense and committed a storyteller as Eugene. After an eye operation he has virtually no eyesight, but he knows the area and provided precise directions. Even from the back seat he realised when I had taken a wrong turn.

We drove through the dry, white landscape – this was mine and mealie world – to the Grasdak lapa, a restaurant and pub. Everyone there knew Vos. Later, Rita and their youngest daughter arrived. Feet up against the wooden counter, we drank Smirnoff Spins, shooters and whisky. There was much talking and drinking. Despite the conviviality I felt awkward and out of place: I remained an observer.

Here the past is still very much alive – an Afrikaner world from pre-1994. I thought about my own circle of friends and other Afrikaners I knew, and wondered how, almost 20 years after the country’s first democratic election, people could be Afrikaners in so many different ways.

Earlier, I had managed to trace Eugene’s Grade 3 teacher. She had remembered him as a well-mannered, above-average learner who offered her peanut butter and banana sandwiches at break. I also spoke to his aunt, Naomi van Etten, who regularly visited the De Kocks on weekends. From the accounts she and Vos gave, it seems Eugene was a sensitive and lovable little boy. When Aunt Naomi came to visit it was the greatest treat for the two boys to creep into her bed in the early mornings and curl up next to her. She was like their older sister.

Top: The De Kock home on a Sundra small holding on the East Rand.

Top: The ten-year-old Eugene (left), with his brother, Vos.

In the 1950s, life for the average Afrikaner boy was simultaneously complicated and simple. Boys were taught to be men; they were not allowed to cry and had to master activities like hunting. Afrikaner children (and, for the most part, Afrikaner women) knew not to question authority: the word of the patriarch, the dominee, the teacher and the government was law. As Max du Preez puts it, ‘God, [the Afrikaner] volk, patriarchy and the Broederbond all came together very cosily.’1

One of Vos’s remarks stood out for me. ‘Just before he died my father told the two of us, “The old lion is dead. They are going to come for you cubs.” This was a warning to Gene.’

At 00:30 that night we stopped at his gate again. ‘Vos, you know what?’ I said. ‘The roof of the yellow house is red now.’

I drove off with a carload of photos and stories.

To understand Eugene better I first had to get an idea of his origins. I decided to go back in time and try to form a picture of him as a child. For information about his upbringing and formative influences, I turned to his family, but also to his own description of his childhood years, written in a report for a criminologist at the time of his criminal case.2

I should actually have been Josias Alexander de Kock, but my father broke with family tradition. The firstborn son of each generation of De Kocks is supposed to have this name. However, when I was born on 29 January 1949, my father decided to call me Eugene Alexander after the writer, Eugene Marais. Father had great admiration for the works by Marais.

Lourens Vosloo de Kock had a successful career in the Department of Justice. He was a public prosecutor in Springs during my early childhood years when we lived on a plot outside the town. Later he was magistrate, regional court magistrate in South West Africa and president of regional courts in Johannesburg.

Mother’s name was Jean, but everyone called her Hope. She was very artistic and she nurtured in me a love of music – opera and light classical music. My parents had divergent interests. My mother had always wanted to travel overseas, but I could never persuade my father to take her. He was conservative and did not like new things. In later years they did, however, travel the country.

Father was Afrikaans-speaking and Mother English-speaking. The children at school3 sometimes teased me and my brother, Vossie, who is 18 months younger than me, about this … My parents also supported different political parties – Father voted for the National Party and Mother for the United Party. Father was also a senior member of the Broederbond, but he never spoke about it. I was still at school when he joined this organisation.

Three of my mother’s brothers fought in the Second World War and all returned. My grandfather on my mother’s side was a British soldier who fought against the Boers and had joined up at fifteen (he added a year to his real age to qualify) to fight in the old republics against the Afrikaners. However, after the Anglo-Boer War [1899-1902] he remained in the country and married an Afrikaner woman who had been in the Potchefstroom concentration camp … My grandfather on my father’s side was a hard-working, honest, straightforward farmer, and my grandmother came from a very refined Afrikaner family.

Top: The De Kock family at their home in Commissioner Street in Boksburg. Eugene is second from the left. His mother, Hope, sits to his right. His father, Lourens, is in the foreground.

Top: Eugene and Vos outside the Boksburg house.

Mother was a widow when Father married her and she was very well off. Her first husband came from an old British family but he died shortly after their wedding after being stung by a bee. I still have a signet ring, which must be about 200 years old, an heirloom he gave her. It is gold and as heavy as a Kruger rand. After her first husband died, my mother inherited a great deal of money but the De Kocks squandered it. Father’s family borrowed money and never returned it … there was this scheme and that scheme. Father bought a car and rolled it, bought a second car and rolled that too – that kind of thing.

While living on the plot, my mother farmed with chickens and made a good living from it. I helped her to slaughter the chickens although I had not even started school yet. It was easy enough to pull the feathers off but when they cut the bird open I realised it was the very chicken we were going to eat that night. Despite my young age, it troubled me that meat or chicken came to the dinner table at a price.

We were raised strictly and with discipline. Father’s word was law; in my parental home I learnt never to question authority. My earliest memory of my father is of him giving me a hiding one weekend when I bothered him while he was busy planting seedlings. I pulled out some newly planted seedlings instead of weeds by mistake.

If I had to describe him in a single word, it would be ‘domineering’. He could be heartless. There was never any praise or recognition for my or Vossie’s good work.

‘If you don’t work, you are destined to become railway porters,’ Father would always warn us. This was his way of teaching us to work hard and to accept adversity. I presume he thought this was the only way in which one could make a success of one’s life. Our school holidays, for example, were never real holidays, because we had to work for most of the time. From the age of twelve I spent my holidays helping out on the small piece of land near Boksburg Father rented from a friend of his. We harvested mealies by hand because he had no combine harvester and we had to drag the grain bag along with us. We worked from daybreak to back-break.

My father grew up during the Depression and had a hard life as a child. His parents lost their farm in the Stutterheim-Komga area. It was a massive farm of a few thousand morgen where they farmed cattle and crops. He attended an Afrikaans school up until Standard 8 and then completed Standard 9 and 10 at Dale College in King William’s Town, where he was taught in English.

After school my father joined the [extreme nationalist organisation] Ossewabrandwag.4 He was arrested, and an English magistrate persuaded him to resign from the organisation. He then moved to Benoni to work at the Department of Justice, starting at the bottom as as an interpreter/messenger. He could speak, read and write fluent Xhosa, and English as well – skills few Afrikaners had.

I grew up in an [Afrikaner] nationalist home and we were strongly anti-communist. Father was a member of the Dutch Reformed Church and, in time, even became an elder. When we were little, he donated a large sum of money for the construction of a new church steeple in Sundra. It was about R700 – a huge amount of money at the time. However, while my brother and I were forced to go to Sunday school, our parents were not regular churchgoers. This troubled me a great deal and the obligatory Sunday school attendance made me so rebellious that as an adult I never became a regular churchgoer.

At first my father was a junior and, later, a senior Rapportryer. He was also a member of the Broederbond’s executive council but later he resigned from the organisation because they refused to acknowledge the black man as a person. My parents taught us that although there were cultural differences between the different racial groups, black people also had rights.

In my early childhood years our family gave me a solid foundation and a strong sense of family loyalty. There was a congenial and warm atmosphere in our house and I always felt safe.

But one evening everything changed. I was six years old.

Father was often disparaging of Mother. She told me later, for example, that before they went to social events he would warn her not to disgrace him. Once they were at the event he always belittled her publicly. Father smoked heavily and was inclined to drink too much. This was when the arguments began.

I had been aware for some time of the atmosphere that had begun to develop in the house because of their conflict. Initially they only quarrelled late at night and tried to hide it from us, but the fighting became more open. One day, after a terrible fight, my bubble of security was burst. Mother got into the car to drive off, and Father didn’t even try to stop her. Vossie and I peered out of the study window to see what was going on outside. He began to cry and was very scared.

I did not cry, but I experienced the extreme anxiety that we were going to be left behind, that my mother was going to desert us. It was a feeling of absolute fear, such as I had never felt before. In later years I would be afraid on numerous occasions, but I never again experienced such intense fear – not during the Border War, the political unrest or even when I was involved in hand-to-hand combat with the enemy.

The 1963 Year Book of Voortrekker High School, which Eugene attended, in Boksburg. He was then in Standard 7 (Grade 9).

My mother was a dear person, kind-hearted and good to anyone in need. I loved her a great deal and was very protective of her. My father was not a bad man, except for the way he humiliated and broke my mother down … He never lifted his hand to her, not even a finger, but personally I would have chosen physical assault over the verbal and psychological abuse he subjected her to. He was an incredibly strong man, but his tongue! He hurt her deeply with his words.

I remember an incident at our home one evening in a fair amount of detail. A group of my father’s friends was visiting. At that stage we were struggling financially and my father had a heated argument with the father of a boy who was in my class at school. I think Father had invested money with him and it was probably the usual story where he had promised him a greater return than he could eventually pay. The men were all half drunk when Father told me: ‘Eugene, go and get the axe.’

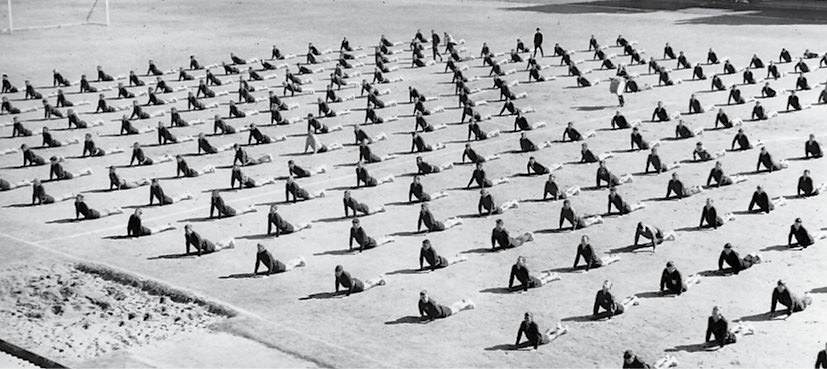

Uniform: This photo of a gymnastrade appeared in the 1963 Year Book of Voortrekker High School.

I reckoned that, seeing the guy had stolen our money, I had better get the axe. Things could end very badly, but what did I know? I was a child and if your father ordered you to do something, you did it. Luckily the man decided to beat a hasty retreat, but it was an ugly episode during which my mother had gone to hide in the bedroom. Mercifully, Vossie was asleep.

Through hard work, Father also managed to get himself out of that financial pickle.

Despite his domineering attitude, Eugene’s father was an important role model. As a young boy he looked up to his father who from a young age had taught him and his brother the basics of hunting. ‘He also taught us to swim, fish, catch eels and even how to slaughter poultry and sheep,’ writes Eugene. It was his father who taught him to drive at the age of eleven, after which he ‘drove for long distances on public and gravel roads, although I could barely see over the steering wheel or reach the clutch’.

Even today, Eugene can clearly remember his first hunt near their house on the Sundra smallholding.

That day I had nothing to do; I only wandered around. I was still too young for a catapult and that sort of thing. The next minute I saw a bird sitting on a branch ‒ it looked at me and I watched it carefully. The bird remained perched on the branch and then it was as if a silence descended. I half looked down and picked up a clod of earth. It lay flat in my hand and, as I threw it, I sensed immediately that it was on course … I hit the bird.

I was scared stiff, but proud because I had hunted. Father always took me with him when he went to shoot the mousebirds that ate his grapes and fruit. I would say from that moment onwards I also felt like a hunter.

I picked up the bird and ran straight to my mother: ‘Look, look,’ I said.

She looked at me with a pained expression. Today I think it may have been caused by what she realised was my loss of innocence. What I saw in her eyes that day I was destined to see many more times in my adult life in the eyes of parents who had lost their children – the infinite sadness caused by total loss. Mother said nothing except that we should go and bury the bird under the vine pergola.

At six I was given my first windbuks, an air rifle, and learnt to shoot. In those years all young boys had an air rifle or a shotgun. Mine was a Falke 70 that was too heavy for me to handle properly, but Father urged both me and Vossie – who had to fire with the rifle rested because he was still so small – to keep practising. He trained us until we could hit a coin from a distance of 15 metres, and we both became dead-accurate shots.

My father was a male role model for us. He was a macho man and a typical Afrikaner.

I was a Voortrekker from Grade 1 to Standard 10 [Grade 12]. Vos and I enjoyed the veld camps a lot. As a result of the Voortrekker camps and my experiences with hunting and fishing, I developed a love of Africa, nature and wildlife. When I was fifteen, I was allowed to go on a camp to Maun and the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

Our vehicle broke down near Maun on the Makgadikgadi pans. We were a mixed group of about 40 Voortrekkers and Boy Scouts – to improve relations between Boer and Brit. It was 1964 and I was the youngest of the group; the rest were all matric pupils. We were lost for about ten days without any contact with the outside world. Even air searches could not find us.

We had enough food but were short of water; we had to dig to find it. I was the only one in the group who was happy and at home in the veld. It was my natural habitat. Then already I saw how big boys and grown men become panicky and belligerent under pressure. They were frightened, especially at night. But I was a fish in water. I felt no fear at all.

From a young age I had taken refuge in books. At primary school I had already dispensed with Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. I read everything I could lay my hands on: Die Swart Luiperd, Rooi Jan, Trompie, Fritz Deelman. I read the Patrys series and even my father’s Justitia5 journals. At nine I received my first Bible, but I rarely read it. When I turned twelve my parents began to order Reader’s Digest books for me.

For as long as I can remember the honey badger, or ratel, has been my totem. The first book that I read by myself was Buks, which was about a honey badger. I can’t even remember how old I was. I was fascinated by the story of the honey badger and the otter who had so many problems with each other.

When I went to high school I started reading Heinz G. Konsalik and in Standard 8 I started on the collected works of [Afrikaans author] CJ Langenhoven. My father owned the entire first edition. I also read all the magazines – Huisgenoot, Sarie, Brandwag, Femina. It is probably obvious that I led a protected life as a child.

Yet I knew from an early age that I wanted to be a soldier one day. As a child I read countless books about the Second World War, particularly about the German armed units, their tactics and so on. In History class at school we also learnt about Napoleon – the battle at Borodino fascinated me. I had great respect for the German soldiers’ capabilities, their training and their precision.

I have no idea why I wanted to become a soldier; nothing pushed me in that direction. It was almost as if it was in every fibre of my being. It was a feeling I had; this was simply what I was.6

The De Kock boys had a strict upbringing. On weekends, Eugene had to do tasks around the house and during the holidays he had to work on farms or do postal deliveries. There was not much visiting or playing with friends. Sometimes he did his homework with one or two friends but there was ‘no running around, not during the day or in the evenings’:7

My father also did not allow us to listen to LM Radio. Look, the 1960s were a different era and anyone who did not listen to Boeremusiek was a ducktail. But on Sunday evenings Mother would slip into my room and push a small radio under my pillow. Then it was my chance to listen to LM. I also enjoyed my mother’s favourites – Sinatra, Chopin, Caruso (still on old 78s), which we would listen to together. This is how my love of classical music developed. My father would not even go to the movies but he would drop my mother and us boys off at movies like Taxi to Tobruk, Polyanna and all the old Afrikaans movies such as Die Onderwyseres en die Bosveldboer and Groenkoring.

Top and bottom:

Eugene and his brother were both members of the Voortrekker movement. These initiation rituals took place during a Voortrekker camp the boys attended. Photo credit: Vosloo de Kock.

At that time, women and children were considered to be a man’s possessions. My father’s word was law and everyone had to dance to his tune … listen to what he wanted to listen to on the radio, do as he said.

The stutter Eugene developed as a young child greatly influenced his school years. His speech impediment was to shape him significantly as a person.

Although I am actually left-handed, at primary school I was forced to write with my right hand. Old Mrs Jankowitz – will I ever forget her name? – smacked my left hand from Grade 1 onwards until I began using my right hand. I don’t know whether my speech problem may have started then. In any case, it did me great damage.

We were all so terrified of our teachers. In Grades 1 and 2 the children would rather wet themselves than ask to leave the room. They would also wet themselves when the teachers began to scream at them. As for me, I froze in fear when they became abusive and I couldn’t get a single word out.

Today I am right-handed, but I can also shoot left-handed, though not equally well. With my left hand I am good with a pistol and above average with rifles. I also write reasonably well left-handed. However, at school I constantly thought I was doing something wrong. You didn’t mention this to your parents – you didn’t want to get another hiding at home. When they eventually realised what was going on, it was already too late. While my mom knew I was left-handed, they weren’t aware of what was happening at school.

I completed my high-school education at Voortrekker High School in Boksburg and in general I cannot complain about my school days. Aside from my speech impediment – which proved a severe handicap and in reality forced me to avoid people – school was not a bad experience. I never failed a subject and while I was an average scholar, in History I stood head and shoulders above my classmates as it was my favourite subject. Geometry and algebra were not my strong point and frustrated me because I did not understand them. In later years, I looked at geometry again out of interest and found that I could, indeed, master it. Did I lag behind or was our teaching inadequate? I don’t know.

What I do know is that the rest was beaten into us, usually with a cane, blackboard compass or a thick plank, sometimes across your back while you were seated. I will never forget how much dust could be raised from a blazer by such a blow.

On occasion I was a class captain – everyone took turns – and later also a prefect. Prefects were elected by all the learners in the school. I presume I was chosen because I treated everyone the same: it made no difference to me which side of the railway tracks you came from (Boksburg North and Boksburg East were separated by the railway line). I was always assigned to the furthest-flung parts of the school grounds where the troublemakers hung out, but never reported any of them.

I had a few very good friends, played rugby and took part in long distance. At home I trained alone by running in the evenings – long distances – and also built a weightlifting system using materials available to me. I even used containers filled with sand.

My weekends were rather predictable. On Friday afternoons I had to mow the lawn and dig the garden beds. Then I had to do some cleaning and my schoolwork until darkness fell. Vos could not help because of his leg. As a young child he was admitted permanently at the Far East Rand Hospital for a few years with TB, first in one leg and then in the other. Mother told me later that on both occasions the doctors wanted to amputate Vossie’s leg, but both times my father had refused – not a son without legs!

Saturdays were nice. There were always rugby matches that lasted until about two o’clock. After that we did homework and then, from about seven to nine o’clock, you could visit your girlfriend. My girlfriend’s name was Estelle. She was in Standard 6 and I in Standard 9. She had dark, copper-red hair and a sprinkle of freckles over her nose. She was a bright girl, always first or second in her class, and she excelled in everything she did. Estelle was beautiful. Her family lived a few blocks away from us, but I would have walked to Upington just to see her for those two hours.

When I arrived at her parents’ house her father would always be on the front porch busy sharpening his pocket knife.

‘Do you know what this pocket knife is for?’ he would say when he greeted me.

‘No, Oom.’

‘To cut it off.’

Thereafter he ignored me until about eight-thirty, when he started to cough.

Estelle and I would spend the entire evening talking in the sitting room, sitting on opposite ends of the couch.

No hand-holding was allowed. By about ten to nine I would start paving the way for the farewell kiss at the front door. When we turned away from each other, we were both weak at the knees. I only wish that at the time I had known more about girls, about the female gender. I mean, even when you had a wet dream, you only imagined your girlfriend’s face and her body down to about her navel – beyond that, you knew fuck-all.

Estelle and I were a couple for almost eight years and I loved her very much. I planned to marry her, but I didn’t want to be poor like so many policemen. I wanted to do things properly and be able to take care of her. At that stage I had to go to Rhodesia [today Zimbabwe] regularly for long periods to serve in the Police Anti-Terrorist Unit (PATU). This meant extra money; I wanted to go one last time to save enough money to buy her an engagement ring.

She said, ‘Gene, please don’t go.’

I would be away for five months. I went anyway – and, ja well, then I received a ‘Dear John’ letter. Of course it was my fault; I should not have gone that last time. I really wanted to marry her, but other men hunted her down mercilessly in my absence.

That was one of the greatest tragedies of my life.8

Eugene’s speech impediment made him an outsider since childhood. He became a young man who swallowed his words and his emotions, who communicated haltingly with the world. He kept quiet in obedience to his father and had an over-developed sense of responsibility towards his mother.

We had few discussions at home. We had to perform our duties and carry out our tasks properly or we got a hiding. I was afraid of my father’s temper. We could not reason with him at all. Because of this, Vos and I took our problems to my mother. She comforted and tried to protect us.

So, there was poor communication between us boys and Father because he was so domineering, impatient, strict and unapproachable. He very often gave us hidings – which sometimes bordered on assault. He was extremely aggressive and he would hit us with a cane until it broke. If we cried he would hit us again. We learnt to suppress our emotions and hide our pain and heartache. I learnt not to cry or look for sympathy.

Top: ‘Every Friday we had cadet practice at school. We were taught how to march and shoot with a .22 rifle,’ Eugene says. He is second from left (with cap and glasses). The man on the far right is a teacher.

In my last two years at school my father and mother both became more involved in my school activities. Why, I do not know and at that point it also did not matter to me. Father supported me during rugby matches and gave me advice when I played lock for the first team in Standard 9 and matric – but by then it was too late …

In time, my parents drifted apart. Mother told me about this and discussed it with me. Yet I never hated my father. I was afraid of him and when he was angry or aggressive I usually avoided him. In later years I stayed away from him too, but kept in touch with my mother and sent her money so that she could have things like a microwave oven – which my father would not buy. It was not that he couldn’t afford one or was stingy; he simply didn’t believe in such things. New innovations did not interest him; he clung to the ‘old days’. It was a struggle to persuade him to buy a TV and a titanic battle to persuade him to get M-Net. That was, again, for Mother’s benefit and to keep her company. Father only watched sport and the news.

Despite their divergent interests, there was a bond of love between my parents. Or rather, a kind of relationship or friendship that kept them together – a friendship based on mutual respect, trust, understanding, support and the I-am-there-for-you principle. Some of these characteristics naturally flew out of the window when Father drank heavily, but always the relationship would be repaired. While Mother was good-natured, hard-working and solid, she could also be volatile when angered. But she was usually the gentle one.

One night in the early 1980s I challenged my father when he again became abusive towards my mother. I told him I would no longer stand for his behaviour. He got aggressive and wanted to start a physical fight. I refused to back down and told him that this was not a father-son issue, that he had to realise my mother was the weaker one. I told him I would no longer tolerate his behaviour, whether directed at my mother or not. That if he raised a finger to her, he would unleash years of pent-up rage in me. Then, we both stepped down.

From that day onwards, my relationship with my father changed dramatically. We developed the kind of bond I had longed for since childhood. From that moment, there was mutual respect and proper communication. This incident still brings tears to my eyes: not the event itself, but the thought of the wasted years that we would never recover.9

Professor Anna van der Hoven is a criminologist who, in 1996, drew up an evaluation report for Eugene’s criminal court case. In it, she wrote that children can acquire aggressive behaviour patterns through ‘family influences, subcultural influence and direct experience’.

She went on to write that ‘in the typical Afrikaans culture small boys were taught to be “men”, and not to cry. They were taught to suppress emotions such as sadness, empathy, tenderness and so on. However, living out one’s aggression was considered acceptable and was encouraged – for example, through contact sports such as rugby.’ 10

According to her, Eugene’s father was the ‘absolute authority’ in the home, an authority that was never questioned or challenged. Furthermore: ‘In the typical Afrikaans home children were indoctrinated to respect the government. Whatever the government decided was be accepted as correct. Further indoctrination was brought to bear by the Voortrekker movement and cadets; in which the accused [De Kock] participated until matric. Afrikaans children were taught to obey authority and not to be critical … The result was that the accused accepted orders from an authority such as the police more readily.’

At 35, Eugene had stood up to his father for the first time. At the same time, however, he strove to follow in his father’s macho footsteps, because this was the route to praise and recognition.