3

Hear the mighty rumbling

En hoor jy die magtige dreuning?

oor die veld kom dit wyd aangesweef:

die lied van ’n volk se ontwaking

wat harte laat sidder en beef.

Van Kaapland tot bo in die Noorde

rys dawerend luid die akkoorde

Dit is die LIED van Jong Suid-Afrika.

At high school we all knew the words of Eitemal’s ‘The Song of Young South Africa’ and sang it with fiery patriotism. In 1968 Eugene, too, knew these words. He was nineteen and on the verge of adulthood. Like most boys of that age he was filled with hormones, not afraid to take risks, giving no thought to their consequences – and far more impressionable than he realised.

My own sons are at this age and already spreading their wings. I find the impulsiveness, drive and physical perfection – and, above all, the fearlessness and unshakeable will to live – of boys in this stage of their lives fascinating. I wonder about Eugene’s nature, and his experiences, directly after school at a time when national service in the military (or police) was not an option but an order.1

Eugene had gone to the Army College in Pretoria in 1967, aiming to study for a BMil degree at Saldanha, but for a variety of reasons things did not work out. Although he enjoyed the training, he was shocked by the junior and non-commissioned officers’ behaviour and foul language. Their sole purpose, it seemed to him, was to break the troops’ spirit. This left him disillusioned with the defence force.2

Eugene at the end of 1967, shortly after he left the South African Army College in Pretoria.

But what the defence force did succeed in was to reveal his calling. The troops were shown the propagandist ‘shockumentary’ Africa Addio (Farewell Africa), which portrays the end of the colonial era in Africa. Among other footage, it shows scenes of the aftermath of the Mau-Mau rebellion in Kenya and the revolution in Zanzibar. Internationally, the documentary was heavily criticised as racist in some circles.

However, it upset Eugene deeply. ‘For the first time in my life I saw the savagery that one human being could inflict upon another. Not only what black could do to white, but what black could do to black. I don’t think I was mature enough to handle the impact [of the film]. In any case, that day I decided that such savagery would never happen in our country – that white people would not be wiped out.’3

Then, at nineteen, he made the decision that would change his life: he wanted to fight terrorism. He left the army after a year and joined the South African Police (SAP), believing he could live out this calling there. ‘Furthermore, this would save me the trouble of having to communicate with others, and I wouldn’t have to humiliate myself any longer. My naivety was blatant. I learnt later that you can run, but you can’t hide from your problems. It didn’t even occur to me that I would have to do ordinary station work and daily policing and that that would entail communicating with the public.’4

In June 1968 Eugene (in the middle photo in the third row, third from right) graduated from the Police College in Pretoria West. He was a group leader.

The first few times I took the road to Pretoria Central, I asked myself if I would ever really understand anything about Eugene’s life. I have never been in the police force, I am not married to a policeman, and have never been in a war. I dislike aggressive men and the blood and guts in horror movies. A natural place to start would be to talk to people who were part of Eugene’s life and work environment.

When I explained this to Eugene one day he looked at me dead serious. ‘Make friends with Larry Hanton. He is like my brother. He can open doors for you if you want a better understanding of things. Take him with you wherever you go. He knows everything and everyone. I’m making him personally responsible for you.’

This was a novelty for me: did I then need someone to look after me?

Larry is a former member of the police’s special task force, also called the Takies, and Eugene’s long-standing colleague and friend. His nickname was Priester (Pastor). I was apprehensive about our first meeting in a bar in Queen Street in Kensington, Johannesburg. Larry was on his way to the 35-year reunion of the Takies and was dressed up for the event in his only pair of long pants and an open-necked shirt. An unobtrusive man, but one not to be judged by his appearance – beneath the calm exterior is an intelligent man with a capacity for razor-sharp observation. He must be shy, I thought later – the entire evening he never stopped talking. He was anything but a gunslinger.

Larry lives on a yacht in Durban harbour and is at peace with the world. He has a soft heart, a sense of humour and the disposition of a true policeman: he wants to get things done. Like all the former policemen with whom I spoke, the police – the ‘Force’ – had been his whole life: it had shaped him. Speaking to me often released a flood of memories with him.

With patience and a great willingness to share his nuanced insight, Larry was my guide on my journey along the track of Eugene’s life. For the next three years he took me into an inner circle of former policemen, Koevoet and task-force members, as well as Vlakplaas operators. Larry opened doors for me that as a woman and a civilian I probably never would have passed through.

One of our first visits was to Koos Brits, who was stationed at Benoni where Eugene was sent after his initial training at the Police College. Brits now manages his transport businesses from two lock-up garages in Pomona on the East Rand. The cement floor of the garage was scrubbed clean, his desk was perfectly aligned and an orderly fifteen or so laminated police certificates hung dutifully on the wall, while nature scenes from a calendar decorated another wall. ‘You have to make the place liveable,’ he explained.

We sat on two chairs and a drum full of oil. Brits is lean, his long beard speckled with grey. How did he remember Eugene as a very young policeman, and what was it like to work for him later?

Brits remembered that first day clearly. ‘It was a Saturday morning and a group of newly trained blougatte was offloaded at the Benoni police station in Bedford Avenue. I was on duty in the charge office and “received” the group. One youngster stood out. He was well built and wore black glasses with heavy frames. Little did I know that he was destined to walk a long road in the history of the SAP. His stutter also struck me.

‘Eugene was allocated to my group; I helped him with his first accident report. Soon he took to the books and wrote exams. It was clear that he had ambition.’

Eugene later became Brits’s section sergeant. ‘Nobody went off duty until all reports were completed,’ he said. ‘Gene had a short fuse, though. He got angry quickly and wouldn’t take any backchatting. When he was cross he began to stutter even more and went pale. Then you knew it was best to disappear.’

Yet he was popular and had many friends, Brits said. ‘And cocky, I tell you.’

He drew deeply on his cigarette. ‘But he was not impossible to persuade. If you did your homework and came to him with a new plan, he would hear you out.’

Later, when I told Eugene about my visit to Brits, it was the remark about his cockiness that got a reaction. ‘You know, the SAP guys may have thought that I kept to myself or didn’t want to talk to them. But I couldn’t talk! Stuttering is hugely stigmatised and I suffered quite badly from it. But I never gave up and simply swallowed my embarrassment.’

In time Eugene was promoted to warrant officer and ordered to form a crime prevention squad. Brits and Larry Hanton were among the members of this squad. ‘It was soon clear that you had to do your work properly or you’d be out,’ said Brits. ‘We were successful under Gene’s command. I admired how he gave you credit if you did good work. On many nights, when the station was quiet, we would braai a piece of meat behind the mine dump in Snake Road. Or sometimes on a Saturday, after a successful day, we would get together for a few beers and have a post mortem before going off duty.’

Eugene’s experiences as a young policeman on the East Rand prepared him, but also started hardening him. Benoni was, in his own words, ‘a hell of a rough place’ at that time, but the policemen who worked with him were ‘seasoned old dogs and even rougher’:

My first day kicked off with night duty at 22h00, a vehicle inspection and, at 22h10, a hotel fight at which troublemakers were breaking the place down. I learnt in a few minutes that night that it was all about survival, not about how you won. I could not believe the barbarism of the whites – against fellow whites.

An old Justitia magazine (top) and a photo of the Police College (bottom). Eugene was such a bookworm as a child that he even read copies of his father’s Justitias.

It also occurred to me that my uniform was the trigger, the detonator, for those who were in conflict with one another to join forces against me as a policeman. It is probably wrong of me to think like this, but we never encountered good or decent people – just troublesome ones. That same evening there were father-beating-mother-half-to-death incidents, and child molestation, trespassing, motor accidents, serious injuries, stabbings, drunk driving, housebreaking and any number of other culture shocks.

When I recall it now, it is as if I am looking at a Salvador Dali painting. The veneer of refinement, law-abidingness and good-naturedness was thin.

Yet that night I realised that a successful career in the SAP was something I wanted to – and would – achieve. The East Rand, especially Benoni, was a good training ground, but one incident is burnt into my memory.

In 1969, two or three days after Christmas, Constable Hennie Coetzer and I were called out to a disturbance of the peace complaint, common at this time of year. It was about 02h00 or 03h00 in the morning when we arrived at the house. As the two of us climbed out of the police van we heard a loud crack but did not think it was anything to worry about.

But at the open front door we came upon a bloodied woman in her pyjamas, leaning against the wall. She had been shot in the chest. By that time we had realised the seriousness of the situation and had drawn our weapons. In the dining room we found a man who had just shot himself; his legs were still jerking. He had a head wound and was beyond help. The man had a 9 mm and a .22 pistol with him, and extra rounds.

In the first bedroom we found two small blonde girls, each with a shot to the crown of her head. In the next room, a woman – dead, also bullet wounds – and two little boys, still very small, shot in the head. In the main bedroom we found a policeman who had been shot in his bed. It was Detective Sergeant Corrie Strydom.

And in the sitting room, a Christmas tree with flickering lights and toys. A house filled with corpses, children’s bodies at Christmas time … and the start of my sleepless nights and nightmares. There was no reason for them to have died. In those early-morning hours I looked up at the heavens and asked: ‘God, are You asleep – why the children?’

A Christmas with a bitter barb. I was barely 20 years old.

Another incident that will always remain with me was a serious motorcar accident that Constable Hennie Coetzer and I came upon in Benoni one Sunday afternoon in 1970 on the Brentwood Park–Kempton Park road. A heavy motorbike had collided head-on with a motorcar.

At the scene we began to follow procedure and took control of the scene, regulated the traffic and made the necessary measurements. I walked to the body of the motorcyclist to make sure he was dead. At first I thought I was hallucinating: from his lower jaw and tongue I could see straight into the gullet. I couldn’t breathe; all I could do was stare. My fingertips went ice cold.

When I had pulled myself together, I went in search of the rest of his head. About 10 metres from the body I found the brain. Another 5 metres away I found the crash helmet, but nothing else. The skull was still missing.

Back with Coetzer, I noticed him looking down at my hands. He asked if I had been injured: my hands were covered in blood. Then I looked inside the helmet and saw the top of the deceased’s skull lining the inside of it.5

Between 1969 and 1974 Eugene completed a total of nine periods of service with the Police Anti-Terrorism Unit (PATU) in Rhodesia. These so-called kitbag squads were so named because their members, most of whom were from the SAP, had to be mobile in the veld and carry all their equipment themselves. For weeks on end they patrolled on foot in the farming and tribal areas of north-eastern Rhodesia, along the Mozambican border. After 1974 the SAP officially withdrew from the conflict, but in talking to former officers I heard that some had secretly stayed behind.

Since I knew very little about our involvement in the Rhodesian conflict I asked Hennie Heymans, a former brigadier, why the SAP had been drawn into a conflict in a neighbouring state. Heymans is the editor of the online police journal eNongqai and an expert on the history of the South African Police. ‘The reason why SAP members were sent to Rhodesia is simple: sending in army troops could be interpreted as an attack on Britain’s rebel colony of Rhodesia,’ he explained. ‘The police, on the other hand, acted as part of a policing initiative.’

In his report for Professor Anna van der Hoven, Eugene wrote extensively on his experiences in Rhodesia and how they influenced him as a young policeman.

Late in 1968 I was called up for my counter-insurgency course and before Christmas I was sent to the Victoria Falls in Rhodesia, where the border base of the SAP’s anti-insurgency unit (SAP-TIN) was. This unit also transferred police members for service in PATU.

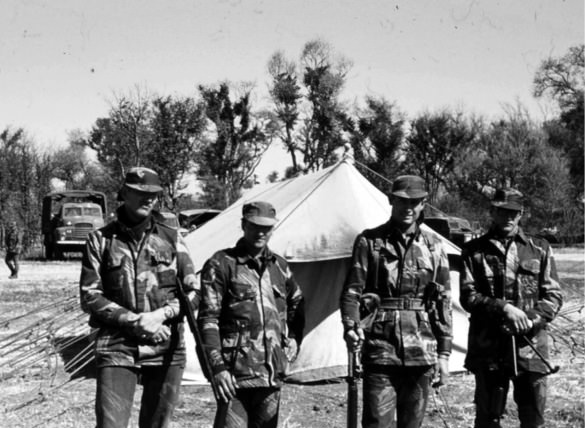

Top and bottom: A very young Eugene during one of his first periods of service at the Police Anti-Terrorism Unit (PATU) in the former Rhodesia.

Although the service period went without incident, a fellow policeman and friend, Constable Cooper from Port Elizabeth, died after falling ill. He died the day after we were supposed to load him onto an air force flight to South Africa. The pilot had refused to transport him, fearing he had an infectious disease such as yellow fever.

The next day we received a message that our friend had died of cerebral malaria. This, after he had complained continually to the doctor at the base that he was sick, and had presented all the symptoms of malaria. But the doctor couldn’t care less – he lounged around all day at the Vic Falls hotel, going to the casino and chasing women. Our friend died. There was talk among the older men that they wanted to teach the doctor a lesson, but nothing came of this. He was later transferred.

That was my first experience of the kind of treatment the wounded and sick received from our own people. Today I have no doubt that this treatment led to the death of many young troops and policemen.

The days in the Rhodesian bush were too comfortable, as if terrorism didn’t exist. However, with my military background I could identify the gaps in our equipment, formations and numbers should it come down to battle. But it was a case of shut-your-mouth-and-get-on-with-your-work. The everything-is-okay syndrome reigned – for as long as nothing happened.

I learnt a huge amount from the Rhodesian instructors and also, of course, from my own experiences and observations. Every time we went to Rhodesia, we were first sent on a three- to four-week orientation course. We had to learn, or re-learn, basic ‘bushwise’ principles. New measures against the terrorists were being implemented – and the terrorists were coming in far more sophisticated, better trained, more determined and in greater numbers. These courses were of huge importance later in my life.

Here I encountered the Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI), who presented some of the courses, but I still felt as if something was missing. On one of the most intensive courses along the Bambeyi River I saw how the Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR) operated. This was the first time I had observed such professional and determined fighting spirit and fighting capacity. For me a black unit such as this, with one or two white members, seemed to be the answer. The white members were very good: less conventional, but still too conventional in the face of the unconventional terrorists they had to confront.

On a subsequent course I encountered Rhodesian Special Air Service (RSAS) officers who were absolutely unconventional and worked in small or large groups, depending on needs and circumstances. But they lacked black members. In my view a combination of the two units – the RAR and the RSAS – would be Africa’s answer to terrorism. I was still too young to be taken seriously and, when I mentioned my thoughts to my friends, their answer was: ‘Fuck the bush, man – we’ve only got a few more days to go. We just want to make it back home.’

Two incidents stand out from this time. The first may not have had such a great impact on me because of my youth and ignorance, but showed the cold-bloodedness and murderous intent of the enemy’s actions. The second shocked me and made me realise that we weren’t dealing with human beings.

The first incident took place in the early 1970s when five SAP members stationed at the Victoria Falls were captured by Zipra/Zanla terrorists while swimming in the Zambezi River.6 One man was kept alive, but the others were taken a short distance away and were summarily executed. When we went to relieve the unit, local people showed us where they had been murdered. The body of the other policeman was never found. Even during the peace discussions between then prime minister, John Vorster, and the Zambian president, Kenneth Kaunda, no answers were forthcoming. Security information that reached us in bits and pieces indicated that the abductee had been tortured so cruelly that he had died from his injuries, and that those who had been executed had in fact been the lucky ones.

I was under the impression that if you surrendered or put your hands up, you would then be protected according to certain stipulations such as those of the Geneva Convention. This belief was finally shattered in 1974 during my service with PATU. I understood from the Rhodesian police that no convention, of any kind, meant anything to these so-called freedom fighters. I did not have a copy of the convention myself and was not trained in convention protocol; I never found one on any terrorist either. Nothing in the actions of SWAPO, the ANC, PAC or Zipra/Zanla ever indicated that they had been trained in these legalities. All we knew was that we needed to capture terrorists alive for intelligence purposes.

Top: Here Eugene stands next to a so-called ‘pislelie’ during one of his periods of service.

Top: PATU members often hunted when they were out in the Rhodesian bush. Eugene is on the far right.

The second incident was really bad. During a second attempt at peace negotiations between Rhodesia and the so-called freedom fighters, with South Africa, Britain and Zambia acting as facilitators, all forces in Rhodesia were told that when the ceasefire came into force, there was to be no firing on any terrorist, even if provoked. The terrorists could also give themselves up and move around freely without weapons.

During this time a group of about seven SAP members and one black British South Africa Police (BSAP) member took two vehicles to Mount Darwin for servicing. On the border, at the Mazoe River, they noticed a group of black men hitchhiking in fatigues. They were members of the Zipra/Zanla forces.

When the front vehicle stopped, one of the men climbed up and held a pistol to the driver’s head. The police members riding on the back of the second vehicle were also held at gunpoint. The hitchhikers then hauled AK-47s from the bushes nearby. All the policemen were captured and taken to a nearby shop where they were exhibited as prisoners and humiliated. The terrorists then left with our men.

At the Mazoe River, they began to shoot at them.

The Mazoe was in full flood. When our men tried to escape they came under fire. As far as I know, only two survived. When the message reached us, we immediately wanted to launch a follow-up operation but the terrorists had moved over the Mazoe Bridge to a ‘frozen’ area to which no other security forces had access. The peace negotiations were still underway and we could not act. The discussions eventually broke down, but by that time it was too late.

This event had an enormous impact on me. I have thought so many times in my life about how our men had no chance. If this was the ideology we were up against, surely we were justified in resisting it with every fibre of our being, using any means? These so-called humanists with their AK-47 rifles were not the democrats they claimed to be. I decided that day to fight against this scum, this rubbish who acted under the banner of justice, with every conceivable means at my disposal.

To rub salt into these raw wounds, about a week later two uniformed SAP colonels turned up at the PATU base and told us that when we returned to South Africa we were not to mention anything about the events at the Mazoe Bridge. I can only hope and pray the events of that day were not orchestrated by the Selous Scouts in an effort to scupper the negotiations. Because I took part in so many covert operations later in my life, I cannot exclude the possibility. I have made many enquiries about this, however, and have found nothing to substantiate my suspicion.

I remember so many incidents as a PATU officer. Our PATU groups were known as ‘sticks’. Each stick comprised five men – four white men and a black officer of the Rhodesian BSAP. A stick was the number of heavily equipped members that one Alouette helicopter could transport safely to a specific patrol area or for an operational follow-up.

Our foot patrols were thorough, difficult and exhausting. Patrols could last from a few days to between 14 and 18 days. We reprovisioned in the veld (in other words: ‘There’s your food, there are your radio batteries, now bugger off back into the veld’). My stick comprised me, two other white members and two black BSAP members.

PATU was sometimes used for enforcing the ‘keeps’, the safe settlements established to protect the local population from Zipra/Zanla guerrilla intimidation and influence. Some of these keeps were attacked periodically. We also provided ordinary services such as setting up observation posts and laying ambushes.

PATU was also used as bait. No guerrilla group would ever leave a small group of five men in peace – they would certainly attack us or try to lead us into an ambush. This would give the joint control centre the opportunity to unleash troops and other groups of the security forces on the guerrilla forces. This is not unusual in warfare and is all part of the job. If you didn’t like it, you might as well pack up and go home or to a base where you could lie and tan all day.

But PATU paid a high price for these tactics. One day, our stick was waiting for a vehicle to pick us up for re-deployment. The pick-up point was a rural trading store. We watched the vehicle approach. It was 150 metres from the store when a deafening sound hit us and the vehicle disappeared in a fireball and a cloud of black smoke.

The vehicle had detonated a landmine with its right front wheel. Given the force of the explosion and the damage to the vehicle, it must have been more than one landmine or a landmine with additional TNT booster charges. The mine had not been buried – it had simply been laid in a deep pool of water that had collected on the two-track road.

The driver, a Rhodesian, was in a critical condition. These Rhodesians – older reservists were usually used as drivers – were hardened veld people and, like this man, they were volunteers.

Top and bottom: The Rhodesian bushveld posed many challenges for soldiers on both sides of the conflict and provided cover for numerous war atrocities.

His visible injuries were to his feet and his lower legs to just under his knees. That was what we could identify. Internal injuries – back and neck injuries, torn retinas, torn brain membranes and burst eardrums – were not our department. The driver was still breathing, and groaning, and blood was spurting from both his ankles in time with the beating of his heart – which was no longer beating as strongly.

It was horrifying. By then I had witnessed many vehicle and motorcycle accident scenes. While I had been at, and investigated, more gruesome scenes than this one, the wounded were always the paramedics’ or ambulance staff’s problem.

This man was not a ‘problem’ – he was one of us. We lifted him out of the vehicle as gently as possible. It was only when he was lying on the ground that the full extent of his injuries struck us. The radio operator had called in the casevac [casualty evacuation] helicopter while the explosion still echoed in the surrounding hills.

No vehicle is landmine-proof. The sandbags in the body of the vehicle and on the floor of the driver’s cab had only made a difference up to a certain point. That point was the driver’s knees … Both Achilles tendons had been torn off the bone; all the veins and smaller blood vessels hung like loose threads, and the bone was pulverised to a fine grit. Higher up between his knees, and also between his ankles, a sort of sack of finely ground bone and liquidised tissue, veins, nerves and muscle had formed.

We staunched the bleeding and made him as comfortable as possible, but he was medically unstable. At that moment the first helicopter began to circle like an eagle above us. We heard, later, that he had been flown to a South African hospital and that both his legs had been amputated below the knees. He survived and was sent back home to Rhodesia.

Today I know it was all for nothing.

The landmine had not been in the water for long; the barefoot tracks led to a kraal 200 metres away. Two men, both elderly, were in the kraal. The footsteps led directly to them. They were arrested but would not say anything. The insurgents had probably given them the mine and told them to place it on the road. The men had just placed it in the pool of water and it had worked. Easy, trouble-free, effective.

They would have had no choice: if they refused, they would have been accused of aiding the security forces, of being anti-revolutionary, and would have paid with their lives that same night.

They climbed dejectedly into the helicopter that took them away for further follow-up investigations and interrogation. What more could happen to them where they were going than what would have happened to them that night had they not planted the mine? Neutrality is no option in this kind of war.

Those who defied the freedom fighters – or, rather, the terrorists – often fell victim to the so-called Rhodesian Way. Early one morning I saw an example of this when Rhodesian security branch officers turned up at the PATU base and requested armed accompaniment to investigate a murder committed by the enemy a few kilometres from the base. The victim had been professionally tortured and killed the previous night, then displayed as a ‘bush message’ to the local black community. What his crime was we will never know, but clearly the rules and legalities of warfare applied only to the security forces and not to the terrorists.

Or were other forces perhaps at work? Was this part of that shadow war so few knew about? I know, now, that covert forces are a widespread phenomenon and that every army or police force involved in a war denies their existence. In all wars there are forces that circumvent the constitution and rules of conventional warfare. Everything is admissable in these forces’ unconventional operations. Their reasoning is: We show the enemy how the war against them will and must be fought – we give them a taste of their own medicine.

A few weeks later I thought of the kraal victim again as I stared at the viciously tortured body of another black man – undoubtedly a victim of the liberation forces. Or was he the victim of a pseudo-terrorist team, perhaps?

The victim had been stabbed with the triangular bayonet found on the SKS rifle and the Chinese version of the AK-47. From his toes to the shins, then in the knees, the thighs, the genitals, then the stomach, the chest, the mouth, the face and, later, the eyes. No single wound would have been fatal at the time of the torture, but surely excruciatingly painful. To the point of death, and back again. I don’t doubt that the man prayed for the release that only death could bring.

I photographed the body and the scene, then the people who stood and watched the exhumation. I wanted to see what I could read on their faces and in their eyes once the photos were developed. The SB men [the Special Branch of the British South Africa Police] did the usual interrogation, but followed the trail no further. We did not remove the body for an autopsy, took no further steps; we left the victim for the people of the kraal to bury as they saw fit. That was that …

Eugene (bottom and above, far right) with fellow soldiers in Rhodesia and the PATU insignia (below).

However, my commanding captain, Captain Adriaan de la Rosa, who had been in discussion with the SB men, called me in and asked me to hand over all the film I had used at the time – particularly the roll that was in my camera that morning – and the notebook in which I had recorded my murder scene observations. The SB men explained that I would get them all back once they had developed the rolls of film, but I never saw them again. In any case, the tortured man was another triumphant victory for the ‘liberators’.

With this image fresh in my memory I ended my service in Rhodesia. Looking back, I think my emotional blunting began with those early experiences as a young policeman in Rhodesia. The resolution with which I departed was that this kind of monster – that we had seen in action from the Belgian Congo southwards – would never be allowed to take over South Africa.

I completed nine periods in Rhodesia, which spanned three to four months at a time. In 1973, for six or seven months I was part of the state president’s guard, but I was very unhappy with my working conditions as they were not what I expected. In 1974 I was transferred back to Benoni and, during that time, I went to Rhodesia again. I was also in South West Africa for two months, where people who murder civilians were hunted down.

In 1975 I wrote my examinations for promotion to lieutenant and passed all my subjects except Statutory Law. I rewrote the subject in 1976 and went on an officer’s course that I passed and completed. After the officer’s course I wanted to get away from the East Rand. I felt I needed to start training myself in station work. The best option would be a small station where you have to do everything yourself and learn from your mistakes.

At my request I switched places with a fellow officer and became station commander at Ruacana, in the northern part of South West. This brought me closer to my real goal: to become involved in counter-terrorism.7

Good and bad, right and wrong, us and them. In Rhodesia Eugene was initiated; he transitioned from boy to man. Two things went almost unnoticed. On one side, his natural leadership came to the fore: Eugene the alpha male awakened. On the other, the principle of ‘us versus them’, ‘me against the enemy’, became ingrained.

It was as if everything that had happened to him thus far came together and flowed, liquid, through a funnel to form the essence of the soldier.

Like many boys, Eugene had from a young age believed in the archetypal ideal of the hero-soldier. In the book Man and his Symbols, compiled by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, I read the following description of the myth of the hero: ‘Over and over again one hears a tale describing a hero’s miraculous but humble birth, his early proof of superhuman strength, his rapid rise to prominence or power, his triumphant struggle with the forces of evil, his fallibility to the sin of pride, and his fall through betrayal or a “heroic” sacrifice that ends in his death.’8

Would Eugene’s ideal of the heroic soldier ever be reconciled with the real world? For how long can a soldier stay true to his seemingly honourable intentions before he is contaminated – by the violence he must perpetrate, or by his own pride?

In her evaluation report, Professor van der Hoven singles out some of Eugene’s important attributes: ‘Strong leadership ability … a quick temper … exceptional endurance, which placed the accused in a position to persevere for a long period while operating in a war situation.’

Shortly before Larry and I left Koos Brits’ lock-up garage that day, Brits said something that made me realise, again, what a decisive influence one’s parents have on one’s life.

‘I think Gene’s entire existence was focused on proving to himself that he was not a softy and could hold his own through thick and thin. The man had difficult childhood years, believe me,’ said Brits, looking pointedly at me, ‘but let’s leave it there.’

Van der Hoven also writes that because of experiences in his childhood years, Eugene learnt to suppress his emotions. ‘As a result he comes across as emotionally cold,’ she says. ‘This also contributed to the heartlessness and determination with which he could pursue and kill the enemy. Because of the long periods he worked in a war situation, emotional blunting gradually occurred.’9

After Eugene’s departure to South West, Koos Brits had only sporadic contact with him: once at Maleoskop, the police training centre in present-day Mpumalanga where Brits was an instructor, and again in 1982/1983 in Koevoet, where Brits went for classified duty. Brits tells of how Eugene nominated him to join C1 – the covert unit at Vlakplaas – a few years later, but that he did not accept ‘mainly because of the opposition of my wife … and that was just as well.

‘I still remember reading Dirk Coetzee’s revelations about Vlakplaas, and the series of subsequent arrests, including Gene’s, one Sunday on the front page of Rapport. Believe me, I was shocked. I knew about some of the operations that the government had ordered, but Gene also crossed the line in some ways. But let’s leave it at that … things happened that were not right and the man received his punishment. The painful thing about this whole episode is how those who gave the orders stabbed him in the back.’

Koos said goodbye with a smoker’s cough and a firm handshake.

‘Did you ever hunt?’ I asked Eugene one day.

‘I must have shot a total of three buck in my life. Then I would exchange it for a buck another guy had shot. I can’t eat something I have killed.

‘I had a bloody rooster that walked around on our plot at the police quarters but once the children gave him a name – it was Red – I said: “Well, you know, we are going to eat Red one of these days”.

‘Audrey protested: “You can’t say that!”

‘The eldest shed a little tear and they chased Red around so I couldn’t catch him. Then I said: “It’s okay, I’ll go and buy a chicken for us.”’

He looked away. ‘You know, once you’ve hunted people, shooting a buck is never the same again. It sounds bad – but that’s how it is.’

The hairs on my neck stood on end.

Eugene left Benoni for northern South West Africa a day or two after Christmas 1976.

‘In considering the accused’s personal circumstances, the court held that the accused had committed the offences within a particular context and period. He sought to act according to an ideology that had influenced him from his youth and that had been reinforced through the influence and example of other police officers and the accused’s superior officers. Both commanding officers and politicians had approved of his actions by giving him awards and commendations, whether he had acted upon instructions or on his own initiative. The accused’s religious convictions, patriotism and belief that his actions would prevent the downfall of a civilised system led his actions to contradict norms he would otherwise probably have followed.’

– QUOTED FROM JUDGE WILLEM VAN DER MERWE’S SENTENCING PROCEEDINGS IN EUGENE DE KOCK’S CRIMINAL TRIAL, 30 OCTOBER 1996.