9

Askari

In his book Askari, Jacob Dlamini writes that double agents – izimpimpi (an Nguni word for ‘spies’) or amaMbuka (Zulu for ‘traitors’) – are nothing new in our society, and points to the treason that took place among Afrikaners in the Anglo-Boer War. The terms describing traitors or askaris are always loaded, writes Dlamini, ‘and their meanings are always context-specific, politically constructed, contested and subject to change. Collaboration is marked by ambiguity …’1

The askaris were unique to Vlakplaas, members of freedom movements like the ANC and PAC whom the Security Branch had arrested and persuaded to work for their former enemy. In exchange for their co-operation, they were remunerated and escaped prosecution. The askaris were indispensable to the Security Branch, helping them to identify their former comrades.2

‘The purpose of Vlakplaas at this stage was ostensibly as a place to rehabilitate “turned terrorists” or, as they were called, askaris. The askaris were eventually divided into units and supervised by white Security Branch members, and it was this change that transformed Vlakplaas into a counter-insurgency unit,’ concluded the TRC in its final report.3

The askari system was an effective and ruthless weapon in the Vlakplaas arsenal.

According to former Vlakplaas askari Gregory Sibusiso Radebe, the average askari blended into society with ease: ‘Ordinary South Africans like you see every day were there. There were also guys of notable intelligence … and that probably is what made that unit the spearhead in the Security Branch’s fight against the ANC. I think it was probably the only unit that could blend in anywhere in the country and bring information in the shortest time possible.’4

Most of the askaris were not prepared to work with the Security Branch of their own accord – they were ‘persuaded’ to do so. According to former brigadier Hennie Heymans, their motivation for becoming askaris varied. Some were disillusioned with the freedom movements they belonged to, others were just plain homesick, while some let themselves be bribed by the salaries and perks. Some clearly knew the consequences of refusing to work with the Security Branch.

Eugene denied, again, to me the allegation that under his command an askari was burnt to death at Vlakplaas while operatives were having a braai. According to him, when the askaris arrived at Vlakplaas they had already been recruited, and were consequently not tortured there. ‘What would actually happen was that on a new askari’s arrival, he would get new clothes, a salary and a pistol for personal protection. Of course, some askaris deny this now because they feel guilty. When the askaris got a hiding, it was because they asked for it. Almost all of them were extremely difficult people.’5

Under Eugene’s command, a few askaris who ‘went astray’ and threatened to leak information about the unit were murdered by Vlakplaas operatives. When I spoke to former Security Branch members, I learnt that in the intelligence world it is common practice to get rid of a source or a colleague whose loyalty is in question. One such askari, Moses Ntehelang, was murdered at Vlakplaas itself.6 (In late December 2014, the Missing Persons Task Team of the National Prosecuting Authority traced Ntehelang’s remains with Eugene’s help.)

Top: Two askaris during training.

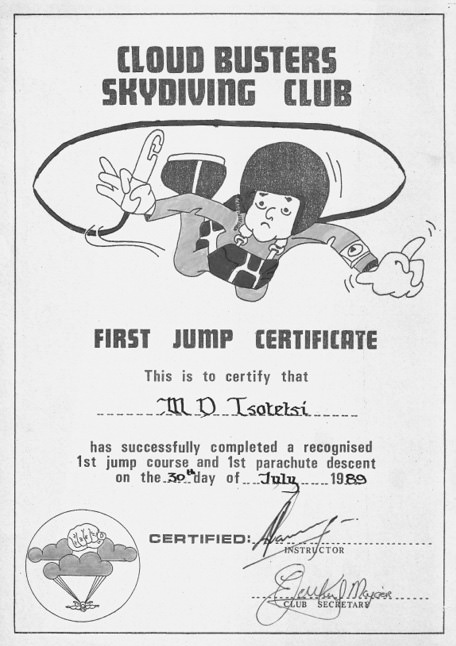

Top: A certificate that was issued to askaris who completed their parachute training successfully.

For Eugene it was important not only to maintain control over the askaris, but also to improve their living conditions. To secure remuneration for them without revealing their involvement in the Security Branch, they were registered as informants. They lived in their own quarters at Vlakplaas; Eugene felt as responsible for them as he did for his black fellow policemen in Koevoet:

I encouraged the askaris to study and improve their knowledge, with the assurance they would get the fees back for all the subjects they passed.

The retraining of the askaris was upgraded to special forces standard under my command, and they were also trained in the use of all types of weapons of Eastern and Western origin. Helicopter drills followed, as well as lectures on the Police Act, standing orders, regulations and law subjects.

There was a large framed copy of the ANC Freedom Charter in the lecture hall. I put it up myself in 1986 and said, ‘Let’s see what I can provide for you on this list.’

A programme resulted that encouraged further studies with financial rewards and saw askaris appointed as permanent SAP members to secure housing subsidies and medical and pension benefits. In this way I provided stability and security for them and their families, and their children had a future and could go to school.’7

Dlamini also refers to the training of the askaris in his book: ‘According to the former askari Gregory Sibusiso Radebe, “we did intense physical training at places like Penge mine and Maleoskop … There was not so much theory, though De Kock liked to have us watch war movies – he seemed to like the movies of the Vietnam war”.’8

Top and above: Askaris at shooting practice and performing other training exercises at the Penge mine.

With colleagues Nick Vermeulen and Lionel Snyman, Eugene also began training the askaris in parachute jumping. Some of the askaris in the first and second group received their wings from Adriaan Vlok, Minister of Law and Order. ‘I received no support whatsoever from my senior officers in this regard. While they were not opposed to the training, I had to devise plans myself to acquire money and parachutes – which we did,’ wrote Eugene.9

Former Vlakplaas operatives whom I talked to all agreed that the first black parachute unit was founded more as a team-building initiative than a fully-fledged parachute unit. Johnny (pseudonym), a former Vlakplaas operative and instructor, explained: ‘The askaris were difficult people. When people compete in dangerous sports or activities, group solidarity develops. That was primarily what we wanted to achieve.’

As Vermeulen – a former task-force member and Vlakplaas operative – said: ‘If you can jump with me, you can fight with me too.’

The main question for Eugene and the Security Branch was the extent to which they could trust the askaris. They were always a source of concern and uncertainty: ‘Consequently, they were reminded in subtle ways that they could not afford to betray the Security Branch,’ Eugene wrote in his application for presidential pardon. ‘I established an internal counter-intelligence unit within Vlakplaas. All the telephones the askaris used were tapped. I used some of the senior black members to listen in on their conversations and report back to me. In this way I tried to find out timeously when an askari’s loyalty to Vlakplaas came under suspicion.’10

At the same time Eugene sympathised with the askaris and their families, knowing that their former organisations labelled them informants.

ANC supporters were directly and indirectly requested to act against these informants. There was no greater treachery, for the freedom movements, than that of the askaris. People suspected of working with the Security Branch were brutally murdered: ‘[I]ndividuals accused of collaboration would have tyres doused with petrol placed around their necks or on their bodies and then set alight … the necklace was a weapon … of the masses themselves to cleanse the townships [of] … collaborators.’11

According to Eugene, firearms could not be officially issued to askaris because they were not members of the SAP. Many did not qualify for weapons licences either since some had criminal records, but they were issued firearms in any event.

‘Some askaris were attacked and had their firearms stolen; others lost – or simply sold – theirs. During the period of unrest and riots I devised a system in which members would guard the homes of those who were on duty. The children of askaris would also be protected at their schools, if necessary … [but] no such situations arose.’12

There was always a chance the askaris’ weapons could by used by freedom fighters in terror attacks. For this reason, Eugene viewed askari weapon losses with deep suspicion. ‘Many of them, according to information we received, considered approaching– or threatened to approach – the political organisations they had betrayed. The murders of Brian Ngqulunga and Goodwill Sikhakhane fall into this category.’13

Eugene described many askaris – and some white Vlakplaas operatives – as ‘difficult people’ who tried his patience endlessly. In addition, he alleged that most of the askaris committed crimes while working at Vlakplaas. He had to use his influence to prevent them being prosecuted, because he feared they would disclose their involvement with, and further information about, Vlakplaas. He found it difficult to discipline the askaris because the danger was always that they might reveal their involvement at Vlakplaas in revenge.

Top: A rare photo of a group of askaris with their instructors during training at the Penge mine.

Top: Braaiing was a favourite pastime for many members of the police.

In Dlamini’s book, former askari Oscar Linda Moni admits to being terrified of Eugene: ‘I had the fear of God that was instilled in me … life as an askari and at Vlakplaas was governed by violence.’ Moni tells of ‘extreme military discipline at Vlakplaas, which was accompanied by occasional beatings, almost on a weekly basis, on the various members who happened to indulge in unauthorised use of alcohol or ill treated their wives’.14

According to Moni, Eugene doled out punishment regardless of race. ‘[A]nybody was a candidate if they should transgress the disciplinary lines that were set.’15

Involuntarily, I thought again of Eugene’s nickname from his Koevoet days: Fok-fok de Kock. He swung between being ‘furious, hopeless, or both’ about the behaviour of his white and black colleagues at Vlakplaas. ‘I controlled the use of dagga and alcohol when I took command at Vlakplaas. Dagga smoking was not tolerated and the use or abuse of alcohol was restricted to times when the men were off duty. I even had to keep an eye on the men’s use of cough medicine because of its addictiveness. One morning I punched Tok Bezuidenhout, a so-called white askari, from under his bottle of cough medicine.’16

I asked Eugene about Moni’s allegation that they got beatings almost weekly. He denied it happened that frequently and explained that corporal punishment was only meted out after a council of black members had decided on it. This council comprised a black SAP captain, two former ANC members, two former PAC members and two black SAP members.

‘A few of them were properly thrashed, but they asked for trouble and got it. One askari challenged me in front of the entire unit: Jimmy Mbane said he was the ANC light-heavyweight boxing champion and would fuck me up. I hit him only once – broke his false teeth, top and bottom, clean through the middle. He had to have another set made when his mouth had healed. He lost his title.’

When Vlakplaas disbanded, all the askaris who were still SAP members were given retrenchment packages. ‘We did this because they were clearly not in a position to do ordinary police work. However, a number of askaris became loyal policemen and kept silent when they were discharged,’ wrote Eugene.17

The extent of the murders, torture and kidnappings by Vlakplaas operatives was revealed in great detail during Eugene’s criminal trial, the evidence he and others gave before the TRC, and in books such as A Long Night’s Damage, which he wrote with Jeremy Gordin, as well as in A Human Being Died that Night by psychologist Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela.

One incident that drew considerable media attention was that of askari Glory Sedibe. Sedibe was one of the young protesters who left the country after the Soweto riots in 1976, joined the ANC and became a member of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). Code-named MK September, he rose high in MK structures. In 1986 he was arrested by the Swaziland police, then abducted from a Swazi jail by Vlakplaas operatives under Eugene’s command. After lengthy torture and interrogation sessions in Piet Retief, he turned. He worked as an askari at Vlakplaas until the early 1990s, when he joined the directorate of covert information. In 1994 he died of a heart attack, although it is alleged that he had been poisoned. In the police file opened on Sedibe while he was still an MK member, a note struck Eugene: ‘He cares greatly for his operatives and agents and takes good care of them.’

A man to respect, even as an enemy.

Eugene’s description of Sedibe’s abduction gives a glimpse not only of operatives’ actions during covert activities, but also of the complexity of the issue of betrayal, specifically in the askaris’ case. In an unpublished manuscript, Eugene writes about this as follows:

On 12 December 1986 there were discussions in General [Johan] Van der Merwe’s office about September Machinery, an Umkhonto we Sizwe unit in Swaziland that was giving the Security Branch a headache. Glory Sedibe was the head of September Machinery.

In terms of an agreement between the South African security police and the Swazi police, Sedibe [after his arrest by the Swaziland police] was held in a small, unremarkable police station with only one policeman on duty at night. This was to give the South African Security Branch the opportunity to kidnap Sedibe and bring him to South Africa. He was well known to the Security Branch as an excellent and successful operative: astute, one who knew the basic rules of security and counter-espionage and was consequently difficult to track down.

On our arrival at the police station, we approached it from a distance to avoid attracting the police official’s attention. Only one light was on in the police station; it was locked up and there was no sign of the policeman. Not a good sign. It was raining, freezing cold in fact. I forced my AK-47 bayonet into a small gap in a window in the administration building, then climbed through with my model 92 Beretta pistol and silencer ready in my hand. I had no doubt that either we had received shit information, or that the situation had changed since we had crossed the border into Swaziland.

The other Vlakplaas operatives followed me in dead silence. This was an ambush. In my mind I could already smell the gunpowder and see the blood, shit and snot spatter as I had seen so often in the past, especially with fights at close quarters.

I heard a shuffle in the corridor and saw a young Swazi policeman with a G3 automatic assault rifle creeping up on us. At three metres I aimed my pistol directly at his face and told him, softly, to put his weapon down. He looked at me, flicked his eyes to his rifle barrel, looked back up at me and saw in my eyes that I knew his safety was on. In my eyes he saw what he had seen in the pistol barrel aimed directly between his eyes – his death. He lowered his weapon, slowly.

Our immediate problem was to find out how many more policemen and weapons there were. We then found the person in charge, who had no rifle. If he’d had one, we would have bled to death in that police station in Swaziland that night.

I took the keys from the official in charge. Opening the cells, we came upon one cell that had three people in it. We locked the two police officials in the cell and chased the other two prisoners – two stock thieves – out into the cold. They were highly annoyed, and moaned about the cold and being fucked around by a bunch of strangers.

Meanwhile, the other six Vlakplaas operatives were fighting Sedibe for their lives. Desperation and the litres of adrenalin pumping through his system were making him give six hardened and fit men – three of whom were big and heavy – pure hell. He was eventually throttled unconscious and carried to the vehicle.

In the vehicle, he came to and got violent again. Out of sheer desperation, one of the black operatives hit him so hard in the face with his Makarov pistol that the silencer bent. Then Sedibe went down. He would wear those Makarov scars on his nose as a medal of honour. As he should have – with pride.18

The askaris’ fates were sealed, from the outset, by their decision to commit treason. Discussing Dlamini’s book, journalist Andrew Donaldson suggests that Dlamini tries ‘to understand Sedibe’s motives, to “explain” Sedibe, and understand why he made the choices he did, to collaborate with a sworn enemy, and to do so without buying, as Dlamini puts it, “into apartheid assumptions about how race determined the moral choices and political loyalties of individuals”.’19

Eugene claims Sedibe’s comrades in Swaziland betrayed him for financial gain. ‘I made it clear at the TRC hearings that MK September was not the traitor they [the Security Branch and the ANC] made him out to be. He was abducted from a prison and brought to South Africa. He was neither a defector nor recruited traitor. He was true MK, and did not do a single thing for money. When I countered the allegations by Colonel Visser [head of the Security Branch in Nelspruit] and his allies during the TRC hearing that MK September was a traitor, they knew only too well not to let the discussion go any further: more answers from my side would inevitably have lead to the disclosure of their ANC sources active in Swaziland and Mozambique.

‘They [the Security Branch] were protecting their ANC sources by creating the false impression that all the information was generated by MK September … Even today they have to protect these sources, some of whom are high-ranking, because these same sources protect them now that the times and the government have changed.

‘MK September’s fate was sealed – in a way, he was already lost when he said goodbye to his wife and young daughter on the morning of his departure to Swaziland. His Judas Iscariot was very well rewarded. In the final instance he was really responsible for MK September’s death; it was as if he had pulled the trigger himself and sent a friend and comrade into the abyss.’20

Eugene believes Sedibe was betrayed a second time in 1994, that he was murdered by ‘the man under whose control he was and who worked for the directorate of secret intelligence … Sedibe was murdered by those whom he had no option but to trust.’ He maintains that Sedibe was killed by the same poison used to murder Knox Dlamini, a Swazi supporter of the ANC.21

There are so many untold stories in the ranks of the erstwhile security forces on one hand and the former freedom fighters on the other … far more than came to light during the hearing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Sedibe’s story is only one of them, writes Jacob Dlamini: ‘But it complicates how we think about apartheid and its legacies, and reminds us of the stories that still refuse to be told. As a nation, we would do well to examine the taboos, the secrets and the disavowals at the core of our collective memories.’22