Nino Pirrotta, an outstanding historian of Italian music, once proposed the title of this chapter as a joke, but it contains an important insight and provides an excellent frame for discussing some issues of major consequence.1 Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), previously best known as a composer of polyphonic part-songs, or madrigals, was also a major player in the “monodic revolution,” the rise to dominance of harmony–supported solo singing in the first decade of the seventeenth century. Owing to the unusual length of his career and the places where he happened to live, moreover, he made distinguished contributions to the burgeoning repertoire of music for the stage during more than one phase of its development. His first “musical tale,” as the nascent opera was called, dates from 1607, his last from shortly before his death, thirty-six years later. The first was performed before an invited assembly of nobles in Mantua and had a mythological theme. The last was performed before a paying public in Venice and had a theme from history. Stylistically as well as socially and thematically, the two works were worlds apart. To all intents and purposes, whether historical, theoretical, or practical, they belonged to different genres. It was the second that actually bore the designation opera, and that still looks like one.

The first was called Orfeo, and it was a favola in musica on the same music-myth previously (and separately) musicalized by the Florentine courtier-musicians Jacopo Peri and Ciulio Caccini. The other, L’incoronazione di Poppea (“The crowning of Poppea,” the emperor Nero’s second wife), was designated a dramma musicale or opera reggia (“staged work”), work being the literal meaning of the word opera, which has stuck to the genre ever since. Both works still have a toehold on the fringes of today’s repertory, although neither is without interruptions in its performance history. They are the earliest and for today’s audiences the exemplary (“classic”) representatives of the noble musical play and the public music drama, respectively. To put it a little more loosely and serviceably, they are the prime representatives of the early court and commercial operas. As Pirrotta implied, comparing them, the common author notwithstanding, will be a study in contrasts and a powerfully instructive one.

Because he was so widely recognized by his contemporaries as the most gifted and interesting composer in Italy, Monteverdi (though he had no hand in its inception) became willy-nilly the spokesman and the scapegoat of the new manner of composing (or seconda prattica, as Monteverdi himself called it). It was captious criticism from detractors that made it necessary for Monteverdi to engage in defensive propaganda. But that redounded to our good fortune, because it enables us directly to compare his preaching with his practice, his professed intentions with his achievement.

By the time he composed Orfeo, Monteverdi had been an active composer for a quarter of a century. His first publication, a book of three-voice motets, came out in 1582, when he was the fifteen-year-old pupil of Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, an important Counter-Reformation composer who had studied with Vincenzo Ruffo and who was the maestro di cappella at the cathedral of Cremona, Monteverdi’s birthplace. By the late sixteenth century Cremona, a city in Lombardy southeast of Milan, was already famous as a manufacturing center for string instruments. The Amati family had established there the workshop where the design of the modern violin family began to be standardized in the earlier part of the century. Antonio Stradivari (1644–1737), who apprenticed with Niccolo Amati, and who is still thought of as the greatest of all violin makers, inherited the Cremonese art and brought it to its peak.

In view of his city’s traditions, it is perhaps not surprising that Monteverdi’s first official appointment should have been as a suonatore di vivuola, a string player, in the virtuoso chamber ensemble maintained by Vincenzo Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua. (As far as we know, however, Monteverdi never composed a single piece of textless instrumental music.) He was engaged in 1590 and remained at the Mantuan court until a few months after Vincenzo’s death in 1612, when he was summarily fired in a notable show of ingratitude by the new Duke Francesco, in whose honor Orfeo had been originally performed.

By then Monteverdi was a famous musician. He had been maestro di cappella at Mantua for eleven years. By the time of his accession to the post in 1601 he had already published four books of madrigals (one of them containing sacred madrigals) and had already been famously attacked by a conservative music theorist named Giovanni Haria Artusi for harmonic liberties in madrigals that would eventually be published in his next book (1603). The controversy enhanced his reputation enormously, especially when he joined in himself, first (and sketchily) in the preface to his Fifth Book of Madrigals (1605). That book made him by common consent, and by virtue of the debates that surrounded his work, the leading composer of madrigals at the tail end of the genre’s history.

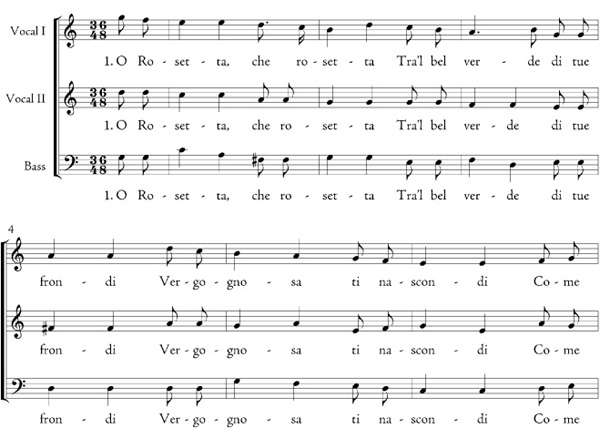

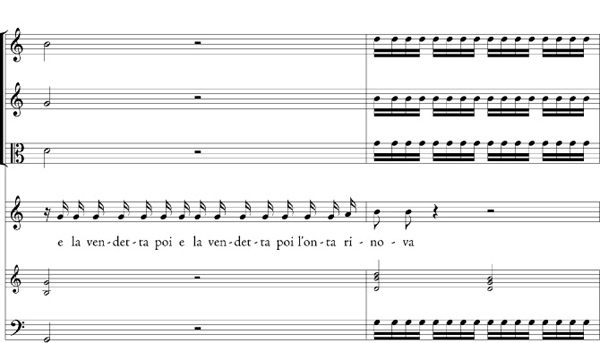

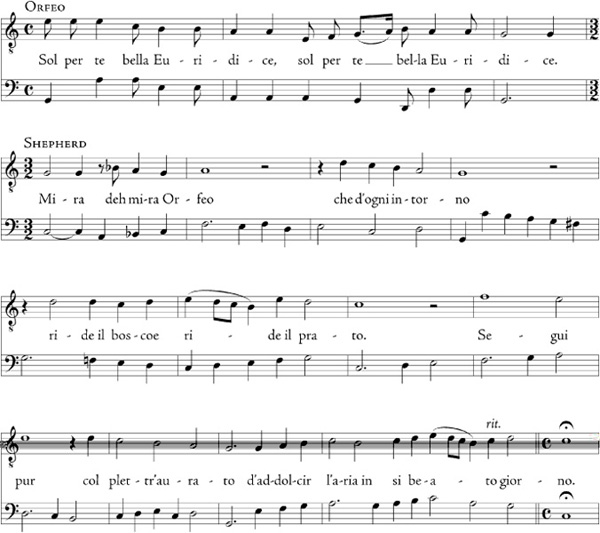

Two years later—in 1607, the year of Orfeo—Monteverdi fully responded to his critics. The answer was included in a new book of what were actually rather innocuous little convivial compositions that he called scherzi musicali (literally “musical jests”): strophic, homophonic canzonetti and balletti (love songs and dance-songs) in three parts to racy “Anacreontic” (wine-women-song) verses by the poet Gabriello Chiabrera, full of catchy “French” rhythms (as Monteverdi called them) based on hemiolas, but without harmonic audacities or any adventurous word painting to speak of. But it was Monteverdi’s first publication to include a basso continuo, and the strophic songs had instrumental ritornelli between the stanzas. This demonstrative use of what was known as the “concerted” (concertato) style, albeit on a chamber scale, was in itself already a deposition in favor of the latest musical techniques and their implied esthetic (for a sample see Ex. 1-1). But the book also contained a formal statement of principles, one that ever since the seventeenth century has been among the most quoted documents in music history.

EX. 1-1 Claudio Monteverdi, Scherzi musicali: O rosetta

The full title of the 1607 publication was this: Scherzi musicali a tre voci di Claudio Monteverde, raccolti da Giulio Cesare Monteverde suo fratello, con la dichiaratione di una lettera che si ritrova stampata nel quinto libro de suoi madrigali (“Musical jests in three voices by Claudio Monteverdi, collected by his brother Julius Caesar Monteverdi, with a declaration based on a letter that is found printed in his Fifth Book of Madrigals).” Using his younger brother, also a composer, as a mouthpiece, Monteverdi wrote what amounted to a manifesto of the “second practice.” The term became standard, as did his famous slogan—“Make the words the mistress of the music and not the servant” (far che l’oratione sia padrona del armonia e non serva), which managed to sum up in a single sound bite the whole rhetorical program of the radical musical humanists of the preceding century.

The discussion of the first and second practices in the Declaration is itself a masterpiece of rhetoric. The chief appeal of Artusi and other upholders of the polyphonic tradition had always been to the authority of established practice. The ars perfecta (the “perfected” polyphonic style) was supreme because it was the hard-won culmination of a long history, not the lazy whim of a few trendy egotists. At first the Declaration seems to honor that pedigree. The first practice, defined as “that style which is chiefly concerned with the perfection of the harmony,” is traced back to “the first [composers] to write down music for more than one voice, later followed and improved upon by Ockeghem, Josquin des Prez, Pierre de la Rue [court composer to the Holy Roman Emperor in the early sixteenth century], Jean Mouton, Crequillon, Clemens non Papa, Gombert, and others of those times.” Finally granting flattering recognition to Artusi’s own chief authorities, the Declaration concludes that the first practice “reached its ultimate perfection with Messer Adriano [Willaert] in composition itself, and with the extremely well-thought-out rules of the excellent Zarlino.” Just what Artusi might have said.

But this recognition of the ars perfecta’s pedigree was only a rhetorical foil. In the very next breath Monteverdi claimed for himself a much older and more distinguished pedigree. “It is my brother’s aim,” wrote Giulio Cesare, “to follow the principles taught by Plato and practiced by the divine Cipriano [de Rore] and those who have followed him in modern times,” namely Monteverdi’s teacher Ingegneri, plus Marenzio, Giaches de Wert, Luzzasco Luzzaschi (a madrigalist who worked at Ferrara and accompanied a famous trio of virtuoso sopranos—the so-called concerto delle donne—at the harpsichord), Peri, Caccini, “and finally by yet more exalted spirits who understand even better what true art is.” Plato, the Monteverdian argument implies, beats Ockeghem any day. Who, in the age of humanism, would dare disagree?

As early as 1610 Monteverdi, rather spectacularly mistreated by his patrons in Mantua, was casting about for a more satisfactory position. Several of his letters testify to his resentment of the high-handed way in which the Gonzagas dealt with their servant despite his standing in his profession. Like the anecdotes that circulated in the sixteenth century concerning Josquin des Prez, they testify to what we might call artistic self-consciousness and “temperament” of a sort that later came to be highly prized by artists and art lovers. But where the Josquin anecdotes are apocryphal, the Monteverdi letters are hard documents, the earliest we have of artistic “alienation.” His hair-raisingly sarcastic reply to an invitation to return to Mantua in 1620 still makes impressive reading, and while it probably marked him as nothing more than a crank so far as the Gonzagas were concerned, it marks him for what we now might call a genius; it has in consequence become far and away the most famous letter by a composer before the eighteenth century.2

By the time he wrote it, Monteverdi had been living in Venice for seven years, serving as maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s Cathedral. He had attracted the interest of the Venetians with a large book of concerted psalm motets for Vespers, plus some continuo-accompanied madrigalistic “antiphons” and a couple of Masses, one of them, unexpectedly, in the stile antico, or old fashioned polyphonic style, based on a famous motet by the sixteenth-century Flemish composer Nicholas Gombert. This Vespers collection was actually written, it seems, in hopes of gaining employment in Rome; and yet its appeal to the home city of the grand concerted (mixed vocal - instrumental) style seems almost predestined.

Monteverdi’s tenure in Venice did not overlap with that of Giovanni Gabrieli, who had died in 1612; there is no evidence that the two greatest Venetian church composers ever met. Nor, contrary to the easy assumption, was Monteverdi hired to replace Gabrieli, who had served not as choirmaster but as organist. (Monteverdi replaced the previous choirmaster at St. Mark’s, a minor figure named Giulio Cesare Martinengo, who died in July 1613.) The position suited him magnificently, in part because Venice was a republican city where the chief cathedral musician enjoyed a higher social prestige than he could ever have attained in a court situation. He stayed on the job for three decades, until his death; after about 1630, however, he occupied the post only nominally, living chiefly on a pension in semiretirement. This, as we shall see, freed him for other kinds of work in his late years.

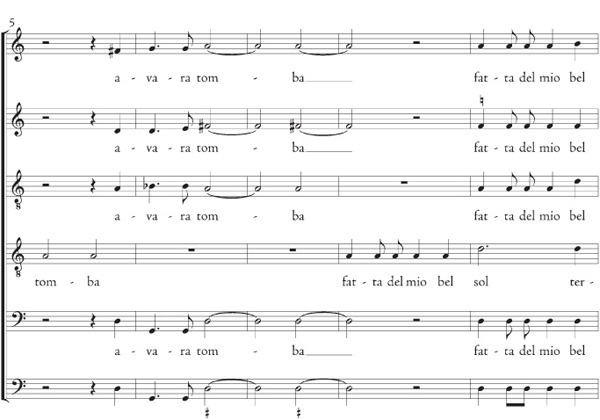

Once in Venice, Monteverdi composed only in the concerted style. He did not publish the service music he wrote in his actual job capacity until his retirement, but he continued to issue madrigals with some regularity, beginning with the Sixth Book in 1614, his last publication in which traditional polyphonic madrigals, left over from his late Mantuan period, appeared cheek by jowl with continuo compositions. They include what could probably be called Monteverdi’s a cappella masterpiece (and probably his last non-continuo composition)—a spectacular cycle of six madrigals, Lagrime d’amante al sepolcro dell’amata (“A lover’s tears at his beloved’s grave”), composed in 1610 to a cycle of poems by Scipione Agnelli that poured subject matter in the recent, racy pastoral mode into an ancient, rigid mold: the old sestina form of Arnaut Daniel, the most virtuosic fixed form of the twelfth-century Provencal poets known as troubadours, as later adapted by the Italian poet Petrarch in the fourteenth century.

(The term sestina, derived from the word “six,” denotes a cycle of six six-line stanzas in which the poet is limited to six rhyme words—that is, three rhymed pairs—that have to be deployed in each stanza in a different prescribed order; the six stanzas exhaust the possible permutations. Writing sensible, let alone moving verse under such constraints is a feat that few poets manage successfully; most sestinas, including Agnelli’s in the opinion of some connoisseurs, fall into the category of valiant attempts.)

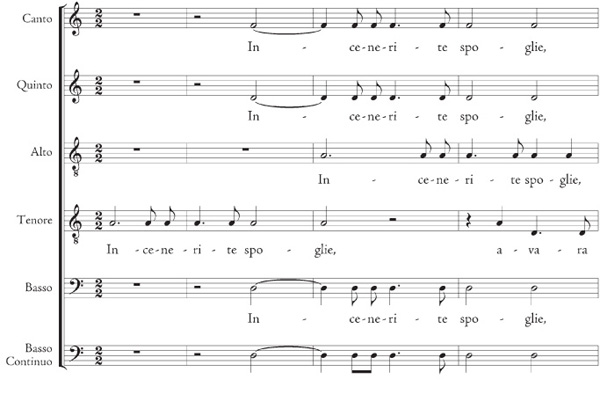

By the time he composed the Lagrime d’amante, even Monteverdi’s polyphonic style had been touched by the monodic stile recitativo, as the opening of the first madrigal (Incenerite spoglie, “Ashen Remains”) vividly suggests. Here, certainly, the words of the spiritually benumbed and torpid mourner at the tomb (clearly identified with the tenor) are the “mistress of the music” (Ex. 1-2), and the static harmony mimics the early operatic style of Peri.

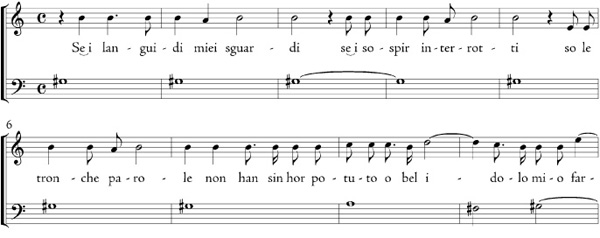

Monteverdi’s Seventh Book of Madrigals, issued in 1619, actually bore the title Concerto. One of its most characteristic items, however, the famous “Lettera amorosa” (love letter), is a monody, the most extended one that Monteverdi ever conceived outside of an actual theatrical situation, or for a single soliloquizing voice. And yet it is theatrical all the same, as Monteverdi recognized by designating the piece as being in genere rappresentativo, “in the representational style.” The style had its technical requirements, notably the static bass, and these are met entirely, so that the whole work becomes an unprecedented 12-minute unstaged scena: music for staging in the theater of the mind (Ex. 1-3).

Monteverdi’s Eighth Book (1638), his last and most lavish in its instrumentation, was called Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi (“Madrigals of love and war,”) and also included a few little works (opuscoli) specially designated as being in genere rappresentativo. The earliest item in the book and, in its inextricable mixture of the martial and the erotic, possibly its conceptual kernel, was a setting Monteverdi had made in 1624 of a sizeable chunk from Gerusalemme liberata (“Jerusalem delivered,” 1581), the celebrated epic poem of the crusades by Torquato Tasso, whom Monteverdi might have known during his early years in Mantua.

EX. 1-2 Claudio Monteverdi, Sestina (Madrigals, Book VI), no. 1 (Incenerite spoglie), mm. 1–9

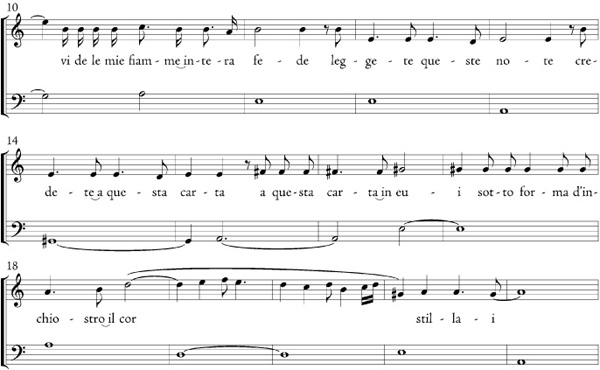

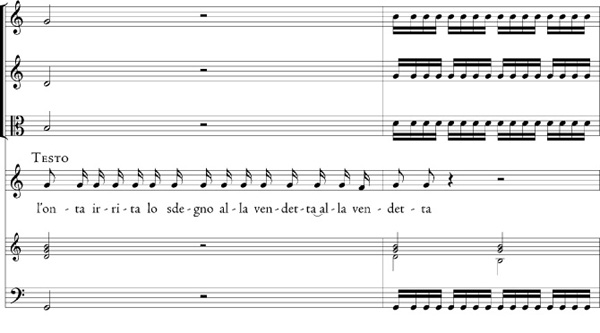

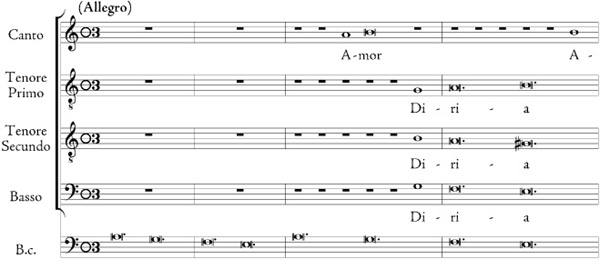

The poem, like any epic, is a narrative, but Monteverdi solved the problem of turning it into a dramatic representation by selecting one of its best-known episodes, called the “Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda,” in which the hero Tancred engages in ferocious hand-to-hand combat with a soldier whom he finally kills, but who in dying reveals herself to be his former lover Clorinda. It is a scene with dialogue, suitable for dramatic treatment, plus a narrator (or the testo, the “text-reciter,” as Monteverdi calls him) who gets most of the lines, and whose graphic description of the gory fight is acted out by the protagonists in mime.

To give adequate expression to this exceptionally violent text, Monteverdi invented a new style of writing, which he called the “agitated style” (stile concitato), and which consisted of repeated notes articulated with virtuosic rapidity. In his preface, Monteverdi related his stile concitato to the Pyrrhic foot of Greek dramatic poetry, which “according to all the best philosophers… was used for agitated warlike dances.”3 (This correspondence was no doubt arrived at after the fact, but like a good humanist Monteverdi reports the “discovery” as if it had been some sort of disinterested scholarly research.) Most of the concitato effects were assigned to the basso continuo and to the concertato string instruments; it was the origin of the string tremolo that has been a dependable resource ever since for imitating agitation both physical (as in stormy weather) and emotional, and linking them. In the Combattimento, the concitato rhythms move imperceptibly from strictly mimetic imitations (the hoofbeats of Tancred’s horse, the clashing of swords, the exchange of physical blows) to more metaphorical representations of conflict. At the very climax of battle, the testo gets to match speed with the instrumentalists to electrifying effect (Ex. 1-4).

EX. 1-3 Claudio Monteverdi, Concerto (Madrigals, Book VII), Lettera amorosa (Se i languidi miei sguardi), mm. 1–22

O my idol, if my languishing glances, my interrupted sighs, my faltering words, have not been able to make you believe in the sincerity of my passion, then read these notes, believe this paper, this paper on which I have poured out my heart.

EX. 1-4 Claudio Monteverdi, Combattimento, fifth stanza, L’onta irrita lo sdegno a la vendetta

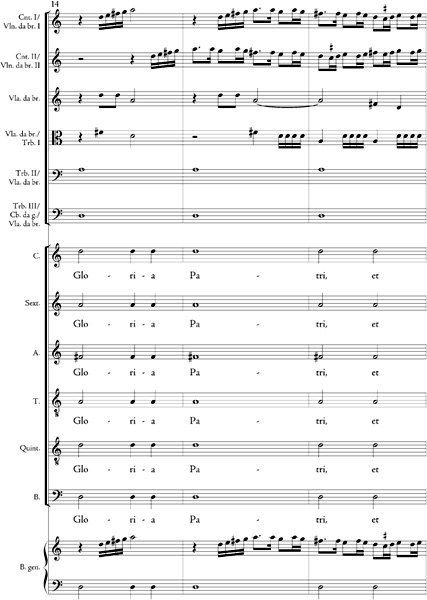

In another “theatrical opuscule” from the Eighth Book, a setting of Rinuccini’s famous canzonetta Lamento della ninfa, “The nymph’s lament” (Ex. 1-5), Monteverdi again turned a narrative into a dramatic scena by framing the complaint of a rejected lover, sung as a solo aria over a ground bass, with narration by a trio of male singers (satyrs?), as if eavesdropping on her grief. The ostinato bass line is no longer one of the standard aria or dance tenors of the sixteenth century, but a four-note segment (tetrachord) of the minor scale, descending slowly by degrees from tonic to dominant—a figure that Monteverdi, through his affecting use of it, helped establish as an “emblem of lament” (so dubbed by Ellen Rosand, a historian of the Venetian musical theater) that would remain standard for the rest of the century and a good deal beyond.4

This was a new sort of dramatic or representational convention: a musical idea that is independent of any image in the poem, that does not portray the nymph’s behavior iconically or hook up with any observable model in nature; a musical idea associated with a literary one, in short, not through mimesis or direct imitation but by mere agreement among composers and listeners. This, of course, is the way most words acquire their meaning. The new technique could be called lexical or indexical (as opposed to mimetic) signification, and it became increasingly the standard way of representing emotion in the musical theater. The most fascinating aspect of Monteverdi’s use of it is the way he plays off its regularity by making the phrasing of the voice part unprecedentedly irregular and asymmetrical for an aria, and the similar way in which he uses its strong and regular harmonic structure to anchor a wealth of strong, “ungrammatical” and otherwise possibly incomprehensible dissonances between voice and bass.

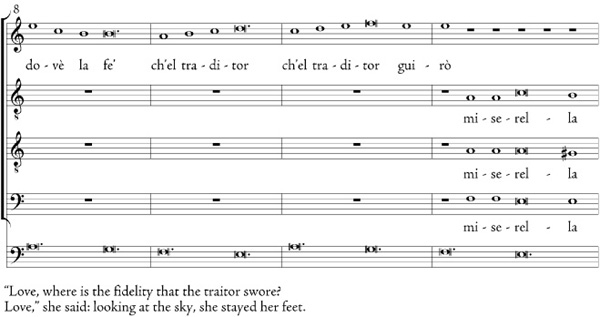

Monteverdi issued most of his Venetian church music in 1641 in a huge retrospective collection titled Selva morale et spirituale (“A Righteous and Spiritual Forest [i.e., large accumulation]).” Most of its contents resemble the contents of the 1610 Vespers collection: continuo madrigals on sacred or liturgical texts, and grand concerti in the Gabrieli mode. One of the latter, a Mass Gloria, sometimes known as the “Gloria concertata,” is a spectacular “theatricalization” of the liturgy, as originally sanctioned by the Counter Reformation. It is utterly unlike any previous liturgical setting of the Mass Gloria, and the very opening is the chief symptom of that difference. Monteverdi’s setting is possibly the first Mass Gloria in which the opening words “Gloria in excelsis Deo” are set to original music by the composer rather than being left for the celebrant to intone as a memorized chant formula. And the reason for this considerable liberty—one that, if not expressly forbidden, would not likely have occurred to any composer as desirable before the seventeenth century—lay in an old madrigalist’s inveterate eye for musically suggestive antitheses, and an old theatrical hand’s ability to render them vivid. What could be more irresistible than to contrast bright “glorious” melismas and the high angelic voices of sopranos caroling “on high” (in excelsis) with low-lying “terrestrial” sonorities and the slow-moving rhythms of peace, its tranquil enjoyment affirmed with mellow chromatic inflections?

So Monteverdi’s Venetian music, while chiefly written for church and chamber, was increasingly couched in theatrical terms: church-as-theater as determined by the Counter Reformation ideal, and chamber theater in the form of opuscoli in genere rappresentativo. What life in Venice did not give him much opportunity to create was actual theatrical music, and that was because Venice, being a republic, had no noble court and consequently no venue for the performance of favole in musica. What actual theatrical music Monteverdi composed during his tenure at St. Mark’s was written on commission from north Italian court cities (including Mantua, his old stamping ground), where there continued to be a demand for intermedii, for favole and balli, or court ballets. Monteverdi wrote (or is thought to have written) at least seven theatrical works between 1616 and 1630, but for the most part their music has been lost.

EX. 1-5 Claudio Monteverdi, Madrigals, Book VIII, Non havea febo (Lamento della ninfa), mm 1–12

The situation in Venice changed drastically when the Teatro San Cassiano opened its doors during the carnival season of 1637. This was the Western world’s first public music theater—the world’s first opera house—and it seems in retrospect inevitable that it should have been Venice, Europe’s great meeting place and commercial center, that brought it forth. “There and then,” as Rosand has written, “opera as we know it assumed its definitive identity—as a mixed theatrical spectacle available to a socially diversified, and paying audience: a public art.”5 This was a greater novelty, perhaps, than we can easily appreciate today, after centuries of public music-making for paying audiences. But it made a decisive difference to the nature of the art purveyed, and learning to appreciate this great change will teach us a great deal about the nature of art in its relationship to its audience. In a word, it will teach us about the politics of art and (for our present purposes even more pressing) about the politics of art history, which like the music theater itself is a genere rappresentativo, an artful representation of reality.

In classical times, and again since the “Renaissance,” or revival of secular learning in the sixteenth century, most history has actually been biography, the story of great men and great deeds. Since the nineteenth century, which was not only the “Romantic era” but also the era of Napoleon and Beethoven, and of a triumphant middle class of “self-made men,” the great men celebrated by historians have typically been great neither because of high birth or hereditary power, nor because of their election by God, but rather by virtue of their individual talents and their ability to realize their destinies, especially in the face of obstacles. (This, we can easily see, is an exact description of both the Napoleonic myth and the myth of Beethoven.) Like Josquin des Prez before him, (see “Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century,” chapter 14), Monteverdi has been Beethovenized by historians. For a long time, the standard account of his life and works was a book by the German musicologist Leo Schrade called Monteverdi, Creator of Modern Music.6

FIG. 1-2 Carnival festivities on the Piazza San Marco, Venice.

An art historiography that is centered on great creative individuals will be a historiography centered on what is called poetics. This word has an etymology similar to the words “poetry” or “poetic”, but has an altogether different meaning and a very useful one that should be kept free of the more commonly used words that resemble it. All of these words stem from the Greek verb poiein, “to make.” The word “poetics” remains close to this original meaning and refers to the creative process, the actual making of the artwork.

The near-exclusive focus on poetics—on making—that is typical in post-Romantic historiography can lead to what is sometimes called the “poietic fallacy.” (The peculiar spelling “poietic,” derived from the Greek root word, is used here simply to lessen the possibility of confusion with the more ordinary meaning of “poetic.”) The poietic fallacy is the assumption that all it takes to account for the nature of an artwork is the maker’s intention, or—in a more refined version—the inherent (or immanent) characteristics of the object that the maker has made.

There has been considerable (quite diversely motivated) resistance to this model of art historiography since twentieth century, and some revision of it. This book will reflect that resistance and revision to some extent. It will pay as much or possibly more attention to larger social, economic, and religious forces as to the personal intentions of composers and theorists. (It could go without saying, but perhaps it had better be said anyway, that complete disregard of such intentions would be just as partial and just as distorted a viewpoint as its opposite: composers are influenced by all sorts of “larger forces,” as are we all, but subjectively—and directly—they are most of all influenced by music.)

And yet when it comes to the neoclassical impulse that gave birth to dramatic music at the end of the sixteenth century, which found expression in so much explicit theorizing, it is hard not to follow the “poietic” model, putting things mainly in terms of artists’ and theorists’ expressive aspirations and achievements. But like any other form of art (at least those that have been successful), dramatic music, of course, had an “esthesic” side as well (from the Greek aisthesis, “perception”), reflecting the viewpoint and the expectations of the audience. (“Esthesics,” like “poetics,” has a more common cognate—“esthetics,” the philosophy of beauty—with which it should not be confused.) In fact the esthesics of dramatic music is perhaps more of a determining factor (or at least more obviously a determining factor) in its development than in any other branch of musical art, and it is very closely bound up with politics. Before we can understand “opera from Monteverdi to Monteverdi”—that is, the differences between Monteverdi’s Orfeo of 1607 and his Incoronazione di Poppea of 1643—that bond has to be explored.

One important aspect of the “esthesics” of early dramatic music was its descent in part from the sixteenth-century Florentine court spectacles known as intermedii. All the earliest favole in musica were fashioned to adorn the same kind of north Italian court festivities, flattering the assemblages of “renowned heroes, blood royal of kings” who were privileged to hear them, potentates “of whom Fame tells glorious deeds, though falling short of truth,” as La Musica herself puts it in the prologue to Monteverdi’s Orfeo—first performed during the carnival season of 1607 to fête Francesco Gonzaga, the hereditary prince of Mantua, where the composer was employed. The words were written by the prince’s secretary, Alessandro Striggio (the son of a famous Mantuan madrigalist of the same name), and the whole occasion had a panegyric (prince-praising) subtext.

FIG. 1-3 Francesco Gonzaga (1466–1519), depicted on a Mantuan coin.

Thus the revived musical drama—the invention of a humanistic coterie of Florentine nobles—reflected (and was meant to reflect) the recovered grandeur and glory of antiquity on the princes who were its patrons. Like most music that has left remains for historians to discuss, it was the product and the expression of an elite culture, the topmost echelons of contemporary society. To put it that way is uncontroversial. But what if it were said that the early musical plays were the product and the expression of a tyrannical class—a product and an expression, moreover, that were only made possible by the despotic exploitation of other classes? That would direct perhaps unwelcome attention at the social costs of artistic greatness. Such awareness follows inescapably from an emphasis on the “esthesic,” however; and that is perhaps one additional reason why the “poietic” side has claimed so vast a preponderance of scholarly investigation.

One scholar who did not flinch from the social consequences of the untrammeled pursuit of artistic excellence was Manfred Bukofzer, in a still unsurpassed essay, “The Sociology of Baroque Music,” first published in 1947. Bukofzer characterized the early musical plays, of which Monteverdi’s Orfeo was the crowning stroke, as the capital artistic expression of the twin triumphs of political absolutism and economic mercantilism, an expression that brought to its pinnacle the traditional exploitations of the arts “as a means of representing power.” It was precisely this exploitation that, in Bukofzer’s view, brought about the stylistic metamorphosis that, following the terminology of his time, he called the metamorphosis from “Renaissance” to “Baroque.” His description is vivid, and disquieting:

Display of splendor was one of the main social functions of music for the Counter Reformation and the baroque courts, made possible only through money; and the more money spent, the more powerful was the representation. Consistent with the mercantile ideas of wealth, sumptuousness in the arts became actually an end in itself…. However, viewed from the social angle the shining lights of the flowering arts cast the blackest of shadows. Hand in hand with the brilliant development of court and church music went the Inquisition and the ruthless exploitation of the lower classes by means of oppressive taxes.7

With the spread of musical plays from the opulent courts of Italy to the petty courts of northern Europe—chiefly Germany, where the first musical play was Dafne, a setting of the Florentine court poet Ottavio Rinuccini’s libretto for the earliest of all favole in musica (originally set by Peri for performance in 1597) as translated by Martin Opitz, court poet of the Holy Roman Empire, with music by Heinrich Schütz, a former pupil of Gabrieli, performed to celebrate a princely wedding at the court of Torgau in 13 April 1627—the costs became ever more exorbitant and the bankrolling methods ever more drastic. “The Duke of Brunswick, for one, relied not only on the most ingenious forms of direct and indirect taxation but resorted even to the slave trade,” Bukofzer reports. “He financed his operatic amusements by selling his subjects as soldiers [in the Thirty Years’ War] so that his flourishing opera depended literally on the blood of the lower classes.”8 The court spectacles thus bought and paid for apotheosized political power in at least three ways. The first and most spectacular—and the most obvious—was the fusion of all the arts in the common enterprise of princely aggrandizement. The monster assemblages of singers and instrumentalists (the former neoclassically deployed in dancing choruses like those of the Greek drama, the latter massed in the first true orchestras) were matched, and even exceeded, by the luxuriously elaborate stage sets and theatrical machinery. Second, the plots, involving mythological or ancient historical heroes caught up in stereotyped conflicts of love and honor, were transparent allegories of the sponsoring rulers, who were addressed directly, as we know, in the obligatory prologues that linked the story of the opera to the events of their reign.

Third, most subtly but possibly most revealing, severe limits were set on the virtuosity of the vocal soloists lest, by indecorously representing their own power, they upstaged the personages portrayed, or worse, the personages allegorically magnified. The ban on virtuosity reflected the old aristocratic prejudice, inherited from Aristotle, that found its most influential neoclassical expression in Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, in which noble amateurs are enjoined to affect sprezzatura (“a certain noble negligence,” or nonchalance) in their singing lest they compromise their standing as “free men” by an infusion of servile professionalism. Giulio Caccini, the leading early monodist, had explicitly revived the concept of sprezzatura in the preface to his famous songbook Nuove musiche of 1601 and in so doing gave some precious insight into the manner and purpose of the moderate, intimate, elegantly applied throat-music called gorgia, comparable in some ways with the intimate style of singing known in the twentieth century as crooning.

Caccini’s preface contained a sarcastic, even cranky comparison between the subtle gorgia he employed and the unwritten (extemporized or memorized) passaggii—real virtuoso fireworks—with which less socially elevated singers peppered their performances. Passaggii, Caccini sneered, “were not invented because they were necessary to the right way of singing, but rather, I think, for a certain titillation they afford the ears of those who do not know what it is to sing with feeling; for were this understood, then passages would no doubt be abhorred, since nothing can be more contrary to producing a good effect.” The matter is couched outwardly in terms of fastidious taste, but the social snobbery lurking within is not hard to discern. Virtuosity is “common.” Those who indulge it or encourage it with their applause are to be despised as vulgar, “low class.” (To find Caccini’s heirs in this antipopulist bias, chances are one need only read one’s local music critic or record reviewer.)

Not surprisingly, virtuosity found a natural home in the commercial music theater. It is only one of the reasons for regarding the Venetian Teatro San Cassiano and the year 1637, not the Florentine Palazzo Pitti or the year 1597, as the true time and place of the birth of opera as we know it now. Where the court spectacles, even Orfeo, now seem like fossils—ceremonially exhumed and exhibited to sober praise from time to time (and dependably extolled in textbooks) but undeniably dead—the early commercial opera bequeathed to us the conventions by which opera has lived, in glory and in infamy, into our own time. From now on, the word opera as used in this book will mean the commercial opera. Anything else will be called by a different name, whether or not its creators chose to do so.

As Ellen Rosand has written, modern operagoers can still recognize in seventeenth-century Venetian works “the roots of favorite scenes: Cherubino’s song, Tatiana’s letter, Lucia’s mad scene, Ulrica’s invocation, even Tristan and Iseult’s love duet.”9 With these references to characters and scenes from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century operas by Mozart, Chaikovsky, Donizetti, Verdi, and Wagner, all pillars of the modern repertoire, and surely not by accident, Rosand has named four potent female roles, one fairly neutered masculine partner, and a delectable cross-dresser. Ever since opera opened its doors to a paying public—a public that had to be lured—it has been a prima-donna circus with a lively transsexual sideshow, associated from the very beginning with the carnival season and its roaring tourist trade. Uncanny, nature-defying vocalism easily compensated for the courtly accoutrements—the sumptuous sets, the intricate choruses and ballets, the rich orchestras—that the early commercial opera theaters could not afford. Never mind the noble union of all the arts: what the great Russian basso Fyodor Chaliapin called “educated screaming” is the only bait that public opera has ever really needed, and its attraction has never waned.

The greatest screamers of all, and the most completely “educated” (that is, cultivated), were the male prima donnas known as castrati, opera’s first international stars, whose astounding sonority and preternaturally florid singing style confirmed opera in an abiding aura of the eerie. Although castrati originated not in the theater but in the churches of sixteenth-century Italy, where females could not perform but a full range of singers was desired, and where (as the historian John Roselli has put it) “choirboys were no sooner trained than lost,”10 the burgeoning commercial opera stage with its exhibitionism and its heroics gave these unearthly singers their true arena. In an age that valued finely honed symbolic artifice, these magnificent singing objects—artists made, not born—were “naturally” the gods, the generals, the athletes, and the lovers. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century “serious opera” is unthinkable (and unrevivable) without them.

Here too there are social costs to consider; for if it was to be musically effective, castration had to take place, so to speak, in the nick of time. That meant that the necessary surgery had to be performed on boys before they reached the age of consent. For this reason the operation was always officially illegal, even though the practice catered in large part to the most official social strata. When Charles Burney, the eighteenth-century English music historian, went in search of information on the practice, he was given a royal runaround: “I was told at Milan that it was at Venice; at Venice, that it was at Bologna; but at Bologna the fact was denied, and I was referred to Florence; from Florence to Rome, and from Rome I was sent to Naples.”

Greedy parents were often responsible; a prospective castrato was supposed to be brought to a conservatory to be tested “as to the probability of voice,” as Burney put it.

But, he continued,

it is my opinion that the cruel operation is but too frequently performed without trial, or at least without sufficient proof of an improvable voice; otherwise such numbers could never be found in every great town throughout Italy, without any voice at all, or at least without one sufficient to compensate such a loss.11

And as other travelers reported, no churchyard in Italy was without a contingent of unemployed or failed castrati, begging for their subsistence. The eunuchs of Italy were not all heroes.

By the end of the seventeenth century the serious—the noble and the heroic—was only one of the available operatic modes. The commercial opera was from the first a bastard genre, in which crowd-pleasing comic characters and burlesque scenes or interludes compromised lofty classical or historical themes in violation of traditional (that is, Aristotelian) dramatic rules, before being segregated by snobbish dramatic purists (in the eighteenth century) into discrete categories of “serious” (opera seria) and “comic” (opera buffa). And this was the other great difference—an even more significant difference—between court music spectacles and commercial opera: the latter, at first under cover of comedy, introduced oppositional, anti-aristocratic politics into the genre. The commercial (later the comic) opera, originally instituted as a carnival entertainment, became a very hotbed of what the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin called “carnivalism”: authority stood on its head.

It was already a license to display operatic divas (women singers, literally “goddesses”), veritable warbling courtesans, to the public gaze, and a notorious Jesuit critic, Giovan Domenico Ottonelli, lost little time in rising to the bait. In a treatise of 1652 called Delle cristiana moderazione del theatro, he denounced the theaters of the “mercenarii musici” (money-grubbing musicians) as voluptuous and corrupting in contrast to the edifying spectacles mounted “ne’ palazzi de’ principi grandi” (at the palaces of great princes).12 But the most significant licenses were as much political as moral and marked the public opera indelibly. Public opera became a world where satyrs romped and Eros reigned, where servant girls outwitted and chastised their masters, where philandering counts were humiliated, and where—later and more earnestly—rabbles were roused and revolutions were abetted. No one had to be sold into slavery to support it; and yet, for the most cogent of reasons, opera became the most stringently watchdogged and censored of all forms of art until the twentieth century, when that distinction passed to motion pictures.

Examples of opera’s disruptive and destabilizing vectors can be drawn from any phase in its history, beginning with the earliest, and the promised comparison of Monteverdi’s two most famous theatrical pieces, sole survivors in the repertory of the court and market genres of seventeenth-century Italy, will make an ideal vantage point for observing them since they epitomized the two artistic and political poles.

Orfeo was officially mounted not by the Mantuan court itself but by an Academy or noble learned society—the Accademia degli Invaghiti (“Academy of those captivated [by the arts]”) as it was called—but that was just a front to make the production look like a gift, since the academicians (whose ranks included both the librettist Striggio and the princely honoree) were all courtiers. Its orchestra surpassed that of any intermedio in its range of colors, although no more than a fraction of the full assembly of instruments plays at any one time, so that relatively few musicians were required as long as their ranks included “doublers” who could take different nonoverlapping parts.

The published score (Venice, 1609) calls for a ceaselessly churning fundamento or continuo contingent of five keyboard instruments (two harpsichords, two flue organs, one reed organ or regal), seven plucked instruments (three chitarroni, two mandolinlike citterns, and two harps), and three bass viols. The string ensemble, which mainly played ritornellos between the stanzas of the strophic numbers, consisted of a basic band of twelve ripieni or ensemble members and two soloists on “French violins” (evidently meaning small dancing-master “pocket fiddles” or pochettes). Finally there was an assortment of wind and brass, some of them reserved for the infernal scenes: two end-blown whistle flutes or recorders, two cornetti, three trombe sordini (“mute trumpets,” probably with slides), five trombones, and a clarino, meaning a trumpet played in its highest register.

The brass colors were to be flaunted first in a toccata (= tucket in English, Tusch in German)—a quasi-military fanfare that, according to the published score, was to be played three times from various places around the hall to silence the audience and invest the proceedings with appropriate pomp. (Contemporary accounts of the premire suggest that a tucket—perhaps this very one—was played before all Mantuan court spectacles; the one in Orfeo—as so often in the case of apparent innovations—was just the first to get written down.) Bukofzer’s point about the interest in ostentatious displays of power that the Counter Reformation church shared with the “baroque courts” is nicely confirmed by Monteverdi’s reuse of the Orfeo toccata three years later in a very uncustomary way to back up the choral falsobordone (choral recitation) for the Invitatory (opening Psalm verse) in his Vespers of 1610 which, we recall, was originally intended for Rome, the Counter Reformation command center. The concluding doxology is sampled in Ex. 1-6.

EX. 1-6 Claudio Monteverdi, Vespro della beata virgine (1610), Deus in adiutorium meum intende (doxology), mm. 14–18

As in the case of Rinuccini’s libretto for Peri’s Euridice, Striggio’s for Orfeo revises its mythological subject to avoid a tragic conclusion. In the myth, after losing Eurydice a second time, Orpheus turns against all women, for which reason a rioting chorus of jealous Bacchantes tears him to pieces. In the Orfeo libretto Orpheus’s father Apollo, the divine musician, translates Orpheus into the heavenly constellation that bears his name, substituting serene apotheosis for bloody cataclysm. There is also a somewhat didactically pointed clash between virtuosity and true eloquence in Orpheus’s great act III aria Possente spirto, his plea to the ferryman Charon to transport him across the river Styx to the Underworld. The aria consists of five strophes over a ground bass. The first four are decorated with flowery passaggii that exploited the famous skills of Francesco Rasi, a pupil of Caccini, who sang the title role. His florid stanzas are sung in alternation with fancy instrumental solos for the “French violins” mentioned earlier, for harp (standing in for the Orphic lyre), and for cornetto. When all of this artifice leaves Charon unmoved, Orpheus, in desperation, drops all pretense of crafty rhetoric and makes his final appeal in unadorned recitativo to a bare figured bass, the very emblem of sincerity. (Charon, while too oafish to respond, nevertheless falls asleep at this, possibly charmed by Apollo, and Orpheus steals his boat; it is the single touch of comic relief.) Above all, and perhaps strangely to us who know what opera has become, there is virtually no love music in this tender favola, for all that it concerns the parting and reuniting of lovers. Orpheus sings on and on about his love for Eurydice, but he does not express it directly through music—that is, to her. Indeed, as it took a feminist critic, Susan McClary, finally to point out, Eurydice, with only a couple of very plain-sung lines in act I and a couple more in act IV, is hardly a character at all in what is at bottom a very decorous, an inveterately “noble,” and an insistently masculine spectacle in its focus on natural male vocal ranges and on the ideal of self-possession.13 This focus is made explicit in the scene where Orpheus loses Eurydice for the second time and a chorus of spirits sing the moral (intended not only for Orpheus but for the young prince Francesco in whose honor the favola was performed): only he who can subdue his passions with reason is worthy of reward. Indeed, the original performance observed the interdiction on female singers in serious places like the palazzi de’ principi grandi, casting the solo feminine roles—from La Musica to the Messenger to Eurydice herself—for castrati or, in some cases, possibly, for boys.

What, then, can account for this oddly restricted work’s enduring hold on audiences, even nonnoble ones, even to this day? Of all the individual acts, the second might best suggest the answer in the way Monteverdi’s music mirrors the implicit point of the whole favola, which is in essence a music-myth, a demonstration of music’s power to move the affections. For in the second act Monteverdi and his librettist contrived a determined clash between “phenomenal” and “noumenal” music, as defined by the critic Carolyn Abbate: music actually “heard” as such on stage, and music that symbolizes the emotions expressed in speech. It concentrates the radical humanist message into a more powerful dose than any other contemporary composer imagined.

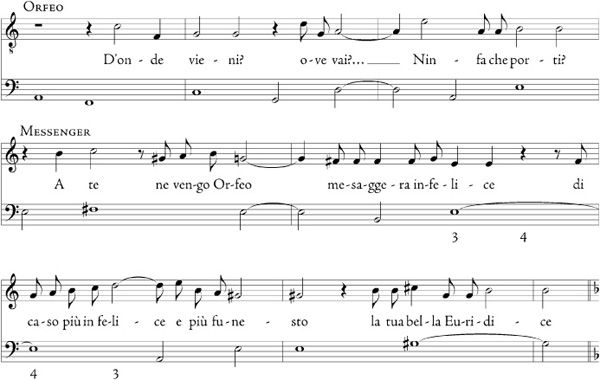

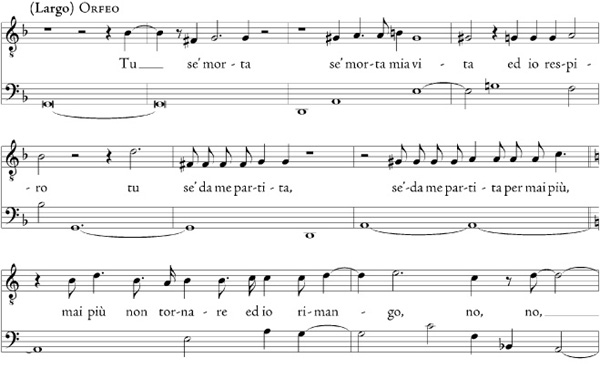

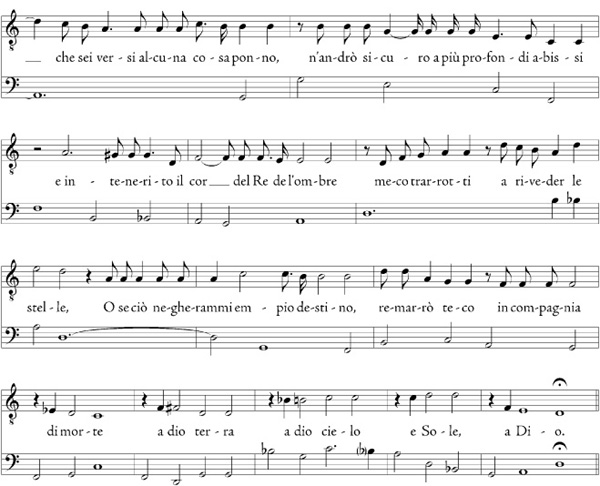

The act begins with a celebration of the wedding of Orpheus and Eurydice. Orpheus, surrounded by his friends the shepherds, celebrates his love. They do it as a kind of concert consisting, after an invocation by the title character, of no fewer than four strophic arias, veritable scherzi musicali with lavishly scored instrumental ritornelli, in all likelihood danced as well as sung. The first three are sung respectively by a shepherd, by two shepherds, and by the full chorus. Then comes Orfeo’s big number, the aria Vi ricorda o bosch’ombrosi, in which he gives catchy vent to his joy, using the elegant hemiola meter Monteverdi designated in his Scherzi of 1607 as “French” (=elegant, as in “French pastry”). Repeated references in the verses to Orpheus’s lyre leave no doubt that he is playing along to accompany the singing, and that the songs and dances are literally that—actual songs and dances performed “phenomenally” on stage.

After Orpheus has finished, one of the shepherds bids him strike up another song with his golden plectrum; but before Orpheus can comply, the baleful “Messenger” (actually the nymph Sylvia) bursts in with the horrible news of Eurydice’s death and silences the stage music for good and all (Ex. 1-7). But the phenomenal music is silenced only so that the noumenal music, the real music of lyric eloquence, can work its wonders on the audience. From here until Orpheus and the Messenger depart the scene (he to fetch Eurydice back, she to hide in shame at having broken such bitter news) no instrument is heard but those of the fundamento, whose music goes symbolically “unheard” on stage.

EX. 1-7 Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo, Act II, messenger breaks in on song and dance

The central business of the act is the exchange between Orpheus and the nymph Sylvia (fulfilling the same function as the nymph Daphne in Rinuccini’s Euridice libretto), which is clearly modeled on, but just as clearly far surpasses, the analogous scene in Peri’s and Caccini’s earlier favole (Ex. 1-8). Monteverdi actually pays Peri the homage of imitation in his deployment of jarring tonalities; but where Peri had contrasted the harmonies of E major and G minor in large sections corresponding to the main divisions of Orpheus’s soliloquy, Monteverdi uses the contrast at very close range to underscore the poignancy of the dialogue psychologically.

EX. 1-8 Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo, Orfeo gets the horrifying news from the messenger

The harmonic disparity between Orpheus’s lines and Sylvia’s symbolizes his resistance to the untimely news she has brought him. He breaks in on her narrative with G minor—Ohimè, che odo? (“Oh no, what am I hearing?”)—as soon as she has mentioned the name of Eurydice (on an E-major harmony), as if to deflect her from the bitter message she is about to deliver, but she comes right back with E major and resolves the chord cadentially to A on the word morta, “dead.” When Orpheus responds with another Ohimè, this time he takes up the same harmony where she left it and confirms it with D, the next harmony along the circle of fifths: the message has sunk in, and he must accept it.

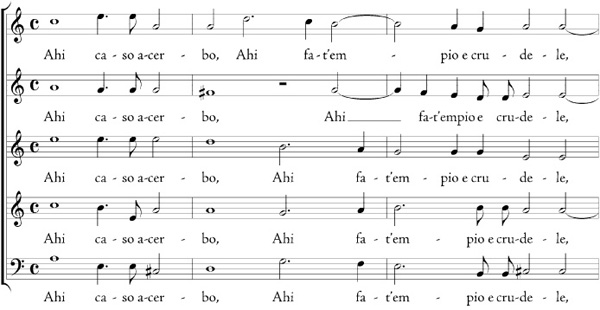

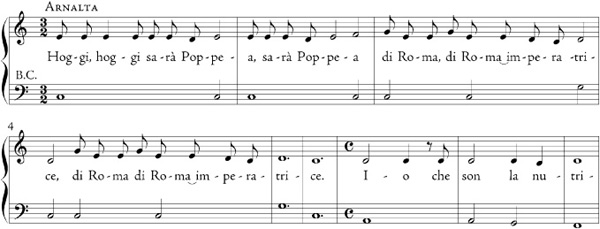

Once again, as in Euridice, the same horrific events are recounted rather than portrayed: not only out of delicacy, but because the composer’s interest is in portraying not events but emotions, those of the Messenger herself and those of Orpheus. When Orpheus finds his voice again after temporarily becoming (as one of the shepherds puts it) “a speechless rock,” Monteverdi again shows his reliance upon Peri as a model, but once again only to surpass his predecessor. Monteverdi’s central soliloquy, like Peri’s, builds from stony shock to resolution, but does so with a fullness of gradation that mirrors much more faithfully—and recognizably!—the process of emotional transmutation (Ex. 1-9). The secret lies in the bass, which begins with Periesque stasis but gradually begins to move both more rhythmically and with a more directed harmonic progression, approaching some middle ground between recitativo and full-blown song. (Later this middle-ground activity would be called arioso.) Orpheus having spoken and left, the chorus strikes up a formal dirge by turning the messenger’s opening lines (“Ah, grievous mischance…”) into a ritornello, the messenger’s notes forming the bass, against which a pair of shepherds sing lamenting strophes that recall the previous rejoicing with bitter irony (Ex. 1-10). Whether to regard the dirge as phenomenal or noumenal music is a nice question; but in any event it is formalized and ritualized emotion that is here being expressed, rather than the spontaneous outpouring that provides the act with its center of dramatic gravity. In this most affecting act of Orfeo, then, the dramatic strategy has been to frame dramatic recitative with decorative aria. The commercial opera would eventually reverse this perspective.

EX. 1-9 Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo, Orfeo’s recitative (“Tu se’ morta”)

In one of the most impressive feats of self-rejuvenation in the history of music, the septuagenarian Monteverdi, bestirred by the institution of public opera theaters, or else offered terms he could not refuse, came out of retirement and composed a final trio of operas for the Teatro SS. Giovanni e Paolo, one of several competitors that quickly sprang up to challenge San Cassiano, the original opera house. The first was Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria (Ulysses’ Return to His Homeland), after Homer’s Odyssey. The second, now lost, concerned another mythological subject, the wedding of Aeneas. The last was L’incoronazione di Poppea, not a mythological but a historical fantasy based on Tacitus and other Roman historians. The librettist was Giovanni Francesco Busenello, a famous poet who was active in the Accademia degli Incogniti (the Academy of the Disguised), a society of libertines and skeptics who dominated the early Venetian commercial theater and did their best to subvert the values of court theatricals for the greater enjoyment of the paying public.

EX. 1-10 Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo, Chorus (“Ahicasoacerbo”)

Busenello’s libretto celebrates neither the reward of virtue nor (as in Orfeo) the chastisement of vice. It is a celebration of vice triumphant and virtue mocked. The librettist’s own argomento or synopsis, published in 1656 in his collected works, puts the story very concisely:

Nero, enamored of Poppaea, who was the wife of Otho, sent the latter, under the pretext of embassy, to Lusitania [Portugal], so that he could take his pleasure with her—this according to Cornelius Tacitus. But here we represent these actions differently. Otho, desperate at seeing himself deprived of Poppaea, gives himself over to frenzy and exclamations. Octavia, wife of Nero, orders Otho to kill Poppaea. Otho promises to do it; but lacking the spirit to deprive his adored Poppaea of life, he dresses in the clothes of Drusilla, who was in love with him. Thus disguised, he enters the garden of Poppaea. Love [i.e., the god Eros] disturbs and prevents that death. Nero repudiates Octavia, in spite of the counsel of [the philosopher] Seneca, and takes Poppaea to wife. Seneca is sentenced to death, and Octavia is expelled from Rome.14

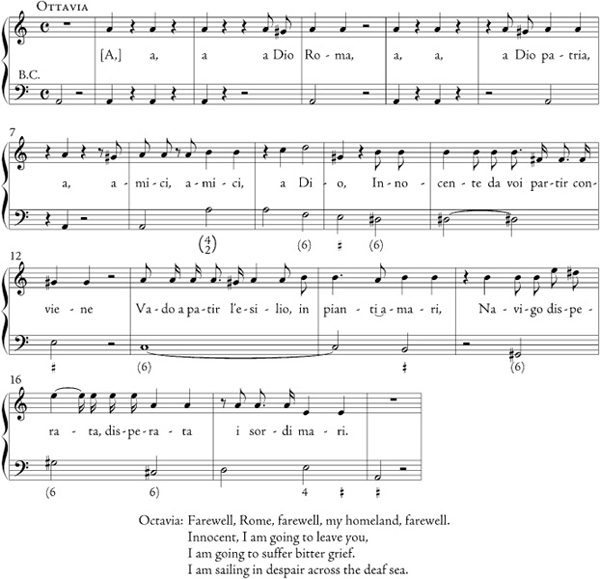

Monteverdi’s setting of this most unedifying—and in places virtually obscene—entertainment has the skimpiest of orchestras (just a little ritornello band notated in three or four staves for unspecified instruments, most likely strings), but it is cast throughout for flamboyant voice types that could never have existed in the court favole: two superbly developed prima-donna roles (the more virtuosic of them the fork-tongued, string-pulling title character, the more poignantly monodic one the wronged and rejected wife), two male parts for shrill castrato singers (the higher of them the feminized, manipulated Emperor Nero, the other the stoical wronged husband), and a quartet of low-born comic characters—one of them, a ghastly crone (Poppaea’s former wet nurse Arnalta) often played by a male falsettist in drag—who spoof, intentionally or not, the passions and gestures of their betters.

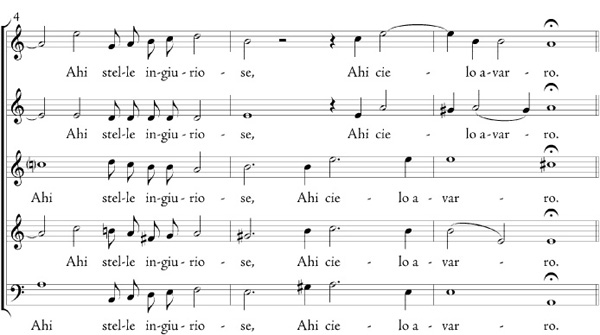

As often in Shakespeare, Monteverdi’s shorter-lived contemporary, the comic scenes are paired with the most serious ones. Thus, the scene in which Seneca carries out Nero’s sentence of death by committing suicide surrounded by his loving disciples is immediately followed by one in which Octavia’s page is shown chasing her lady-in-waiting, coyly singing the while that he is “feeling a certain something” (Sento un certo non so che) between his legs. And the opera’s most tragic moment, Octavia’s farewell to Rome as she boards the ship that is to take her into exile (Ex. 1-11), is followed immediately by the most farcical—Arnalta’s gloating at her mistress’s impending elevation, and her own (Ex. 1-12). Elsewhere the page, the opera’s “lowest” character, directly mocks Seneca, its most exalted one (Ex. 1-13).

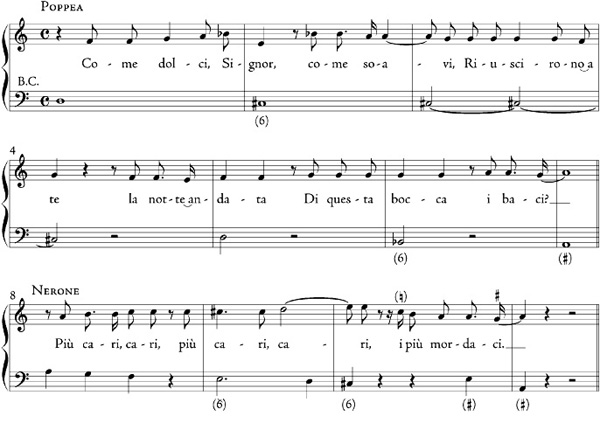

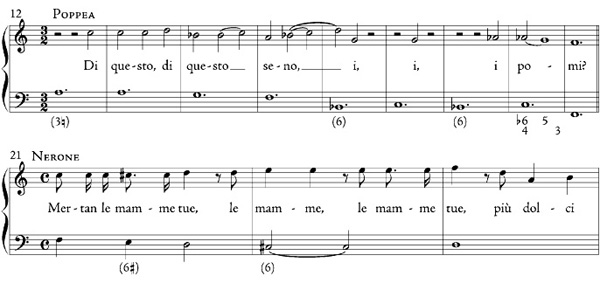

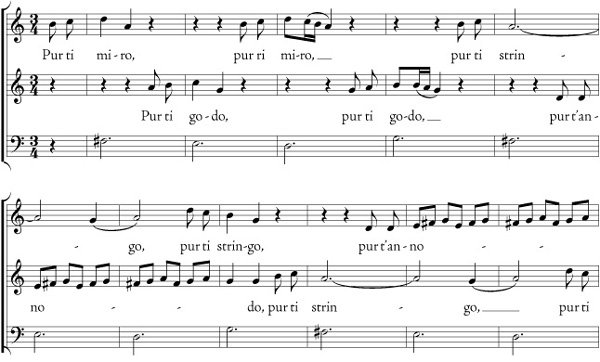

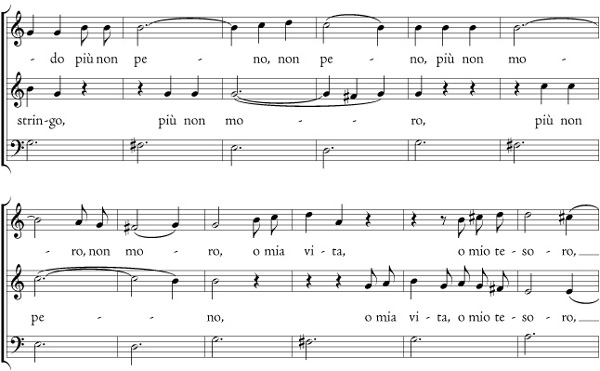

The relationship between Nero and Poppaea is represented frankly as lustful, and that lust is given graphic musical representation. In an early lovers’ dialogue, Poppaea flaunts her lips, her breasts, and her arms at Nero, and the composer, taking on the role of stage director, seems to prescribe not only her lines and their delivery but her lewd gestures as well. Nero, in response, makes explicit reference to their sexual encounters, even to “that inflamed spirit which, in kissing, I spilled in thee” (Ex. 1-14). And in the opera’s famous culminating number, the duet Pur ti miro, an arching, bristlingly sensual lust duet (for two sopranos, impossible to savor today at full outlandish strength even when the part of Nero is not transposed to the range of a “natural” man but sung by a woman), the music, in its writhing, coiling movements, the increased agitation of the middle section, and the dissonant friction between the singers’ parts (or between them both and the bass: see especially the setting of the words piú non peno, piú non moro in Ex. 1-15), leaves no doubt that the lovers are enacting their passion before us, whether or not the stage director dares show them in the act.

EX. 1-11 Claudio Monteverdi, L’incoronazione di Poppea, Act III, scene 6 (Octavia), mm. 1–18

EX. 1-12 Claudio Monteverdi, L’incoronazione di Poppea, Act III, scene 7 (Arnalta), mm. 1–28

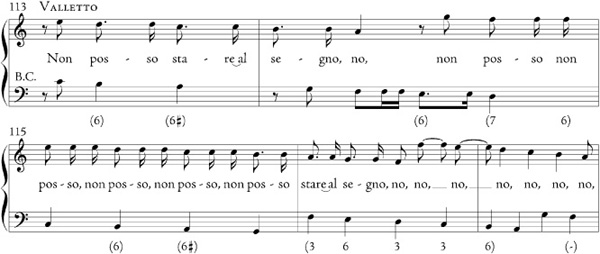

EX. 1-13 Claudio Monteverdi, L’incoronazione di Poppea, Act I, scene 6, mm. 113–41

This duet, of which the final, opera-ending section is given in Ex. 1-15, symbolizes and formally celebrates in the guise of a ciaccona, a slow dance over a mesmerizing ground bass (again a descending tetrachord at the beginning and the end, but in the lubricious major rather than the lamenting minor), a craving that has subverted all moral and political codes. (Its form, with a contrasting middle section and a reprise of the opening “from the top” [da capo], would become increasingly popular with opera composers and eventually replace the strophic aria.) Where Orfeo, the court pageant, celebrated established order and authority and the cool moderation that its hero tragically violates, Poppea, the carnival show, brings it all down: passion wins out over reason, woman over man, guile over truth, impulse over wisdom, license over law, artifice (in persuasion, in the singing of it, in the voice itself) over nature.

EX. 1-14 Claudio Monteverdi, L’incoronazione di Poppea, Act I, scene 10, mm. 1–38

EX. 1-15 Claudio Monteverdi, L’incoronazione di Poppea, final scene, no. 24 (ciaccona: Pur ti miro), end

Scholars now agree that Pur ti miro, once thought to be the aged Monteverdi’s sublime swan song, was not written by him at all, but by a younger composer (maybe Francesco Cavalli, Monteverdi’s pupil; maybe Benedetto Ferrari; maybe Francesco Sacrati, now regarded as the prime suspect) for a revival in the early 1650s. Only that version, presumably one of many that circulated in the theaters at the time, has survived. And so it is now the standard text, but it had no such status in its own day. That is another difference between the court spectacles and the earliest real operas. The court operas, performed once only, were then printed up as souvenirs of the festivities for which they were composed in fully edited, idealized texts that resembled books. These scores could become the basis of later productions (and did so in the case of Orfeo), but that was not their primary purpose.

Commercial operas, by contrast, were not published at all until comparatively recent times. Like today’s commercial (e.g., “Broadway”) musical shows, they existed during their runs and revivals in a ceaseless maelstrom of negotiation and revision, existing in a multitude of versions—for this theater, for that theater, “for the road,” for this star or that—and never attained the status of finished texts. It distorts them considerably even to contemplate them from the purely “poietic” standpoint that has become the rule for “classical music.” They were esthesic objects par excellence, not texts but performances, embodying much that was unwritten and unwritable, directed outward at their audience, not at history, the museum, posterity, the classroom, or any other place where poietics is of primary interest.

Once again we observe that the fully textual (or textualized) condition we associate with “classical music” and its permanent canon of masterpieces came into being much later than many types of music that eventually entered its orbit, sometimes with distorting or invidious result. And yet the commercial opera never did altogether supplant the courtly, since they occupied differing social spheres and have only lately met, uneasily, on the modern operatic stage.

Ever since 1637, then, the world of opera has been a divided world, its two political strains—the edifying and the profitable, the authoritarian and the anarchic, the affirmational and the oppositional—unpeacefully coexisting, the tension between them conditioning everything about the genre: its forms, its styles, its meanings (or its attempts to circumvent meaning), its performance practices, its followings, its critical traditions. The same political tension lies behind every one of the press skirmishes, reforms, and “querelles” that dot operatic history (and that we shall be tracing in due course), and it informs the intermission disputes of today. Nothing else attests so well to opera’s cultural significance, and nothing else so well explains the durability of this oldest of living musical traditions in the West.