1

Anger in Teens: The Problem and the Solution

So, you’ve considered all of the “w” questions of the introduction and are certain you’re in the right place. Before we launch into the PURE method—its skills and strategies—you must first understand the nature of your teen’s anger. Without the right conceptual hooks to hang your new skills on, your good intentions may simply fall by the wayside.

In this chapter you will:

- Develop your appreciation for the needs and possible mental health factors driving teen anger.

- Learn about the unintentional communication patterns between parents and kids that keep anger in the picture.

- Begin to engage in practices of mindfulness and positive psychology, and learn how these concepts are embedded in the PURE method.

The Ancient Context for Anger

Imagine trading in your living room, illuminated by the glow of its flat screen, for a fire-lit cave with a cold stone floor. You’re a prehistoric human and a saber-toothed tiger is preying on your family. Without anger, what would you do? How would things turn out for you and your kin? What would happen to the human species?

For millennia anger has protected and sustained us against physical threats. Our brains evolved limbic, or emotional, processing structures to spark us to self-maintaining action—that is, to fight, flight, or freeze reactions. These have allowed us to survive dangers and persist through to the present day.

What if, as prehistoric humans, we sat cross-legged in a full-lotus position outside the mouths of our ancestral caves, meditating with eyes peacefully closed for hours on end? We might cultivate some presence, but that flame of awareness would soon be snuffed out. (Hungry tiger, anyone?). Without anger—without the fierce flailing of indignant energy to fight, to protect ourselves—in such a perilous world all that meditating would matter little.

While our capacity for anger is natural and necessary, it carries a price. Even though our modern world has largely traded curtly worded text messages for tigers, anger continues to ignite us to reactive action. Our brain’s ancient architecture knows no difference. It thus shakes us with the same urgency. Yes, anger is natural. However, just because something is natural doesn’t mean it’s ideal. The modern mind needs mindfulness as a corrective antidote to what eons of evolutionary changes have trapped within our skulls.

Few contexts bring out the prehistoric urges in us like parenting. A few years ago, one winter morning before preschool, my daughter was not having the idea of wearing a coat.

“Celia, please put on your coat.” I was running late—for a session in which I’d be preaching mindful parenting of all things.

“No,” she barked. “I’m not wearing it!”

Cue the caveman within. Running late… My agenda… She’s being ridiculous… Doing this yet again, on purpose… The thought parade trampled all semblance of presence from my brain.

“Put on your coat, Daddy’s going to be late.”

“No!” she screamed, flopping on the kitchen floor. The shoes I’d barely managed to jam on her feet flew across the room. “No coat!”

Remember, I teach mindfulness. I emphasize its importance to every trainee, workshop participant, and parent I work with. And that morning, I grabbed up Celia’s coat, bent down close to her in the kitchen, and snarled, “Put on your fucking coat!”

She froze and allowed me to press the coat around her.

We were both quiet on the way to school. Usually Celia is a chatterbox, but that day, strapped into her car seat, she sat in atypical silence. A tsunami of shame crashed down on me. I, a mindfulness loudmouth, had let my anger f-bomb on my own daughter.

From the quiet of the backseat, Celia broke the silence: “But, Daddy?”

“Yes, Celia.”

“Daddy, I don’t want to wear my fucking coat.” Her voice was as sweet as my guilt was sour.

I share this less-than-glowing testament to my own parenting because the evolutionary, brain-based reactive surge of anger appears to be universal. Anger is never going to leave you completely, nor will it ever fully leave your teen. However, anger need not be the toxic theme of your teen’s life, nor of your relationship. There is a path for provoking change in your teen’s brain. This book guides your journey along that path. Your journey starts with understanding the causal factors of your teen’s angry struggle.

Where There’s Smoke: What Sparks Teen Anger

Teens send parents messages through their behavior, especially their most off-putting, anger-laden actions. I organize these messages under the acronym RSVP—I’ll explain what the letters stand for in a minute—because for parents, the key is to respond (or RSVP) to the real message beneath their teen’s behavior, not just to react to the nasty face value of the behavior. In many situations, your teen’s anger is an attempt—sometimes intentional, but often not—to announce that certain core needs aren’t being met, or are perceived as being unfairly denied, particularly by you.

For teens, anger tends to well up when they feel they’re not getting:

- Respect: Teens may flare during interactions with a parent because they assume their parent thinks they don’t deserve respect. Teens often believe themselves to be more capable than their parents will admit.

- Space: Teens often want a parent to give them the physical and emotional room to try things out—to explore life without a parent’s rules, reminders, and identity. Teens want their own identity.

- Validation: Teens generally experience things intensely. A teen’s emotions are often strong and in flux. With all this intensity—and, believe it or not, because your perspective can have a great deal of impact—your teen sometimes looks to you for validation. Or, to use a less therapy-thick term, teens want to know a parent understands and accepts their feelings as real.

- Provisions and Peers: Teens also frequently want provisions or stuff from parents. This could be access to fun and distraction, this could be money. Provisions in this sense are primarily a route to connecting with peers. Teens generally want the acceptance and sense of belonging only peers can provide—and clothes and screens can seem like the keys to such experiences.

I’m sure none of these needs greatly surprises you. Perhaps you remember the importance of these when you were a teenager. Regardless, the mere knowledge of your teen’s motivators isn’t what will make the difference. Rather, it’s your ability to communicate that you get it—that you realize, though you may not agree, that these things are very important to your teen. Communicating this will do much to create connection, and will serve as fuel to help improve your teen’s behavior and capacity for managing the demands of daily life.

Remember: teens come by their anger honestly. Always. Your teen has no grand plan to screw with you. There’s no early morning agenda that unfurls when a teen’s eyes first open in the morning. While your teen certainly does things on purpose to irk, agitate, deflate, and deflect you, your teen doesn’t plan to get mired in anger and suffering.

Q: So, are you saying my kid shouldn’t be held accountable for his rants and destructive outbursts? That I should just let him off the hook because his anger problem is not his choice?

A: No, that’s not what I’m saying. Yes, your teen does things on purpose—in the moment—to back you up or draw you in. But he doesn’t intend for this cycle of suffering to repeat over and over. Still, he needs to be held accountable for actions that displace or hurt others. Accountability does not equate with complete culpability.

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (2011), psychologists Steven Hayes, Kirk Strosahl, and Kelly Wilson make the helpful distinction between clean and dirty emotions. Clean emotions are primary, basic reactions to stimulation from the environment. Clean emotions communicate a basic message that something is right or wrong for us. Clean anger occurs when someone directly and dangerously threatens your well-being, whether that’s physically or psychologically. Here, anger, true to its primal roots, motivates us to take action to right our circumstances.

Dirty anger is different. Dirty anger is what our thoughts do in reaction to primary emotions. So, for example, dirty anger might cause us to assume accidental pain was caused by someone on purpose. We might become indignant and respond with, “How dare you!” Dirty anger is a layer of unnecessary mental muck we heap upon a primary emotion, be it anger, fear, or otherwise. It’s a bit like taking one of the colors of a rainbow—the ROYGBIV you learned in middle school art class—and mixing it thoroughly with the others. You end up with a brownish, dirty mess.

We’ll discuss why the human mind mixes up our emotional palette like this later. For now, know that our minds are constantly trying to protect us. Your mind registers emotions and makes snap judgments to help keep you out of harm’s way. Problems occur when your system reacts out of proportion with the actual risks of a situation, or when you’ve been down a certain emotional road before and consequently now have a hair trigger for frustration.

This dirty anger is happening to you and to your teen. Teens’ minds are trying to protect them as well. The whole system between you and your teen can become way out of sync—especially if deeper clinical factors are prompting your child’s anger.

Mental Health Factors in Teen Anger

Sometimes a significant underlying clinical cause, such as depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress drives a teen’s anger and acting out. To help your teen, it’s important to consider—with professional input—whether your teen’s anger goes beyond typical RSVP messages. Your teen’s anger may derive from something that requires professional help.

In the 2010 National Comorbidity Survey, Dr. Kathleen Merikangas and colleagues interviewed over 10,000 American teens and found that about 32 percent met criteria for a diagnosable anxiety disorder at some point in their lives, 19 percent met criteria for a behavior disorder (such as oppositional defiant disorder), 14 percent for mood disorders (such as major depressive disorder), and about 11 percent for substance use disorders (Merikangas et al. 2010). Clearly, a large number of teens struggle with impairing emotional difficulties.

As a psychologist who has worked with at-risk, troubled youth for over fifteen years, I’ve heard a wide range of comments from parents grappling with the idea that there was some underlying clinical disorder driving their teen’s anger. Here’s a sampling:

- “When he really gets going with an intense episode—when he’s really losing it—I can’t help but get terrified that this time he’ll do it. This time he’s really going to hurt himself or someone else.”

- “What do you mean she’s sad? She sure doesn’t act that way. To me, she’s pissed off at the whole world.”

- “I have to walk on eggshells with him. If I don’t help him sidestep things he doesn’t want to deal with, then I become the target—I’m to blame.”

- “Sure, I know she’s had a lot on her plate with our divorce and all. But I went through a lot of stuff too when I was her age, and I never dished it out to my parents and others in the family the way she does. There’s no respect whatsoever.”

- “He has no friends. He’s burned all his bridges.”

Clinical conditions can manifest with significant angry behavior for adolescents, well beyond the RSVP reasons for anger. Though space does not allow for an exhaustive discussion of these conditions, I want to emphasize a few important points.

Anger Can Serve as a Mask for Depressed Mood in Teens

Anger can surface as a defensive crust for the overwhelming emotions and thoughts related to a depressive condition. I’ve noticed this with many boys I’ve helped and some girls as well. These teens may have extremely poor self-concepts. Some may feel so hopeless that they’re actively considering suicide. They may not show much overt sadness, however, with the result that their depression can go undetected. This, in turn, can add to feelings of being unnoticed and unworthy, particularly by their family. Angry lashing out at loved ones, teachers, and other caregivers helps these teens feel a sense of control they have largely lacked. They typically don’t believe themselves capable of having much positive impact in their lives—and don’t expect good things to come their way. Anger becomes a predictable companion. They know what to expect with anger, even though it often leaves them with collateral damage at home, at school, and with peers.

Anger Can Give Teens a Way to Escape Intense Experiences of Anxiety

Stereotypically, we think of anxious kids as the wilting lilies of classrooms and gym class—the kids who shrink back, who work to keep out of the spotlight and below others’ radar. And yet, some teens struggling with angry emotions and behavior may have a deep reservoir of fear lying just beneath their surliness. These teens are trying to avoid feeling deeply unsettling fears. If you block their escape routes—their preferred methods to duck and cover—you can end up experiencing the brunt of their anger. For example, some extremely anxious teens will attempt to opt out of school by feigning illness. If you, in responsible parent fashion, nudge them to go to school anyway—totally unaware of the cyberbullying from peers that’s fueling their fear—you become the recipient of a tongue lashing. They make you out to be the worst parent ever, who yet again fails to fix things or understand what they’re going through.

Anger Can Develop as a Self-Protective Mechanism When Teens Have Experienced Significant Loss or Trauma in Their Lives

When teens experience intense loss, physical or emotional abuse, or neglect, pain can lodge itself deep inside. Teens may be unable to sort through this pain alone. Perhaps a loved one has recently died, or they experienced trauma at the hands of someone they trusted, or a stranger took advantage of them. In cases like these, anger can become both the primary messenger, announcing that the psyche has been wounded, and the main method of defense against further injury. The underlying message is as follows: “If I lash out, I’ll be able to keep people at a distance—I’ll be able to keep them from hurting me again.” It feels risky to show the hurt and fear resulting from these traumatic experiences, so instead they show anger. Parents are a safe dumping ground for teens’ emotional pain. What a teen can’t hold internally is temporarily managed by slinging it on to you.

You’re likely well aware of the grief or trauma your teen has suffered—but your teen’s anger can still be hard to face. While in quiet moments you may be able to compassionately connect with your teen, in moments of blazing anger such compassion can feel light years away.

Anger Can Be the Primary Clue that a Teen Has Suffered or Failed in Some Way in Relationships with Peers

Teens can be cruel. Teasing, slurs on Facebook, crushing your teen’s reputation in the rumor mill—peers can be attacking your teen and you may be the last to learn of it. Perhaps your teen is engaged in a tit-for-tat, but that doesn’t mean your teen deserves everything other teens are dishing out. You can end up the whipping-parent for your teen’s peer-related pain. Your teen’s anger can be a wake-up call that your teen needs your help. Remember, many teens spend much of their waking life thinking about and obsessing over how they stand with their peers. When peer relationships go poorly—when your teen has been maligned or rejected—it can fuel anger.

Deciding If It’s Time for Professional Help

If your teen’s anger appears to be a clear reaction to a neglected RSVP—that is, if your teen appears to feel disrespected, intruded upon, emotionally invalidated, or blocked from tangible stuff the teen wants—then you may be able to manage things on your own. If, however, your teen’s anger is long-standing, highly disruptive to daily self-management, toxic to the functioning of your household, or is escalating into severe episodes of aggression, depression, or risk-taking behavior (such as unprotected sex or substance abuse), then professional intervention is crucial. While it is never easy emotionally to reach out to professionals—and can be expensive, inconvenient, stigmatizing, and anything but a sure thing—in these cases the risks of going it alone are too great.

Professionals experienced in working with adolescents have knowledge, training, and the perspective you lack by nature of being a parent. While professionals aren’t perfect and may disagree with one another, they can provide the lifeline families need in clinically significant situations with teens. This book is a resource, but it is not a living, breathing guide who can address the specifics of what’s happening in your family.

It Takes Two to Get Tangled in Anger

We’ve surveyed some of the core factors that create anger problems for teens. Now let’s turn to solutions. This book focuses primarily not on your teen’s problem behavior, but on improving the communication between you and your teen.

A more connected relationship is possible even when things have been toxic between you and your teen. The remainder of this book will help you maximize the chances for creating this connection.

All parents of teens who are struggling need a heaping dose of hope that things can change for the better. They can. This book, however, isn’t about the future. Rather, it’s about what you’re communicating to your teen in the present moment. What you’ll find is that, as communication improves, your teen’s problem behaviors generally improve as well. Building communication and relationship skills between parent and teen can go a long way to addressing both the now and the long term.

As a family therapist, I once worked with a single mom and her fourteen-year-old son. Despite having a great deal of intellectual ability, this teen had struggled in school for years. The teen’s primary obstacles were an angry, irritable mood and attention difficulties; these disrupted his ability to focus as well as to feel competent socially and academically. After weeks of escalating behavior at home (and refusals to leave for school) morphed into months, the mom was desperate.

Amid pained looks out the office window, she told me, “He’s going to ruin his life if he keeps this up… No one gets what’s going on here—not even people in my own family. They either just blame me, blame him, or both of us… I end up doing one of two things: I either give him anything he wants to get him out of bed and onto the bus—chocolate for breakfast, even the gift card I had in my purse—or I end up screaming and threatening to send him away to one of those wilderness programs.”

Crying, she added, “He’s so damn smart and yet he’s failing at school. Sometimes I’m convinced he’s just conning me, doing all this shit on purpose to get what he wants. Maybe I’m just a damn fool.”

When son and mother sat together in my office, their postures aimed away from each other as if they were battling magnetic poles, each shoving the other away. The back and forth continued:

“I’m done with that school. It’s full of retards and I’m not going.”

“You need to watch your language.”

“Why? I don’t give a shit,” the son said. “You think I’m too stupid to cut it in college anyway, so what’s the use?”

“There he goes with the disrespect again. It never stops!”

“Just back off me, or I’ll make you wish you had! I know your boyfriend has about had it with you because of me, so don’t think I won’t make it a little more likely he leaves.”

“See, Doc? There’s no helping this kid,” the mother said. “Maybe you can talk some sense into him.”

There was a time in my work as a clinician focused on adolescents and their parents that I would have talked to this family about the tug-of-war going on between them. I would have focused on the issues of power and control that led to these outbursts. I would have worked to give them strategies to meet their control needs in other ways.

However, over the years I’ve found that although this approach could be helpful at times, it was only helpful to a point. It missed something. It treated the tug-of-war between parent and teen as if it were a bad thing, a problem to be dropped. What I’ve learned—and what research increasingly supports—is that when teens and parents struggle most, this tug-of-war needs a different sort of attention. Instead of dropping the tug-of-war rope, parent and teen need to hold on. They need to learn how to keep themselves tethered to one another in healthy ways that get their respective needs met.

This particular boy needed medication and other therapeutic interventions to address underlying attention and emotional issues. However, the relationship between mother and son needed addressing as well—and the problem was not the rope, it was how they were holding it. What they needed was a new way of communicating.

The Anatomy of Parent–Teen Communication

Over millennia, the human brain evolved in response to demands to communicate with others in our species (Wilson 2004). Humans weren’t the fastest, strongest, or even toothiest species around, yet we came to dominate the planet due to our capacities for symbolizing experience through language. With thoughts and images, humans were able to both represent experiences internally and develop the physical and psychological capacities to express these to one another.

The interconnected structures our brains evolved not only help us communicate, they also help us develop emotional “ropes” that tether us together. (Psychologists call this attachment.) Together, language and attachment shape the drama—the highs and lows—of relationships.

You cannot not communicate. Think about it: you cannot look someone in the eyes without, in at least some very small nuanced way, sending the person a message. Try it. Sit or stand facing someone—stranger, friend, family member, it doesn’t matter. Set a timer for thirty seconds and then look each other in the eyes. Try very hard not to communicate anything to the other person.

You will fail. As have the hundreds of people I’ve done this exercise with, you will inevitably send some sort of message. Why? As biologists increasingly argue, our brains are wired for communication (Goleman 2007; Seigel and Hartzell 2004). We evolved as communication gurus. Anger is part of this cerebral hardware. Our capacity to flare at one another helped us survive in harsh, prehistoric environments when predators came our way.

We do not, however, live in caves anymore (though the unkempt state of your teen’s room might suggest otherwise), and we do not have saber-toothed tigers breathing down our necks. While the modern world certainly holds dangers, relative to our ancestors’ world, today we live in daily safety.

And yet, we continue to have the same biology—including the parts of our brains involved in experiencing and expressing anger. We all trip over our brain’s wiring when sending messages to loved ones, because we all still have brains designed to scan our environments for danger and jump to the conclusions necessary to keep us alive. Further, our brain’s attachment system ties us together with strong emotions, flooding us with anger, resentment, fear, and (insert any other negative emotion here). Our brains were not built for the modern age of nuance, mixed messages, and family complexities, where inner calm in the face of threat is much more advantageous than is an angry swipe of the fist.

Again, we all trip over the three-pound relics in our skulls. There’s no blame in that. There is, though, responsibility. As the parent, the messages you send will set the tone for communication with your teen. Remember, you cannot not communicate. So, setting aside the constraints of your brain’s architecture, what messages do you want to send?

As you’ll experience when you engage in the activities and practices of this book, you can change your brain’s wiring. The science is increasingly clear (Lazar et al. 2000; Vestergaard-Poulsen et al. 2009): the brain physically changes in response to many of the strategies I describe here. Consequently, you can alter your patterns of communication—and new, healing messages can get through to your teen.

And from you, your teen can learn to send such messages as well.

What Makes a Communication Breakdown?

A communication breakdown begins in the microseconds when our mirror neurons—specialized brain cells that react to emotions and actions of others—fire faster than our thoughts and intentions can keep up. Thinking, taking perspective, and feeling compassion in response to someone’s behavior happens in the cerebral cortex, an evolutionarily more recent place of the brain.

When we observe someone doing something emotional, our mirror neurons spark the older, emotional centers of the brain to process this information before our cerebral cortex does or can. As a result, we see our teen’s emotion—and begin reacting intensely ourselves—much more quickly than our cortex can produce grounded, compassionate thoughts. Our cortex stumbles along, trying to keep pace with the emotional brain. The fact that this happens behind both sets of eyeballs yields the breakdown—your and your teen’s poor frontal lobes barely stand a chance!

If you tried the eye contact exercise described previously—and if you haven’t yet, I recommend trying it with someone now—you will have discovered that you quickly failed because you couldn’t help communicating in some way. When you locked eyes with the other person, your respective brains were on fire with activity, priming reactions to what you were seeing. When that other person is your own child, particularly one with whom emotions and messages have been challenging, communication easily gets sidetracked.

Remember, struggling teens do the aggressive, antagonistic, disruptive, and sometimes downright dangerous things they do in order to send messages. They are looking for you to RSVP—to give them the respect, space, validation, and provisions for connecting to peers they feel are lacking or threatened.

Research suggests that parents whose communication with their teens is filled with conflict messages are more likely to disengage—that is, inadequately communicate; such disengaging contributes to less parental monitoring and greater risk for behavioral or substance abuse difficulties among young people (Dishion, Nelson, and Bullock 2004). Again, communication breakdowns aren’t just about a loss of control, they’re complicated at a brain-to-brain level. Communication breakdowns are about the nuances of rapidly processing information in the brain combined with a lack of methods for initiating real, loving messages between parent and teen.

Here’s a more hopeful finding: parent–teen relationships marked by closeness, open communication, and reduced conflict have been shown to facilitate teens’ development of self-regulation skills, emotional well-being, and positive social behaviors (Masten and Coatsworth 1998).

Let me emphasize, there are no June Cleaver–shaped genes for good parenting. It’s not that some people are born expert at managing challenges with teens. However, communication skills based in mindfulness and positive approaches can actually change the physical structure of the brain and make helping your teen much easier.

The Destructive Dance Between Parents and Teens

This may seem surprising, but parents and teens also mutually teach each other to escalate things. As with what’s happening at a biological level in the brain, this learning—called operant conditioning—happens without anyone choosing it. It’s largely unintentional and no one’s really to blame. That said, you can learn to recognize and interrupt this pattern with the tools presented in this book.

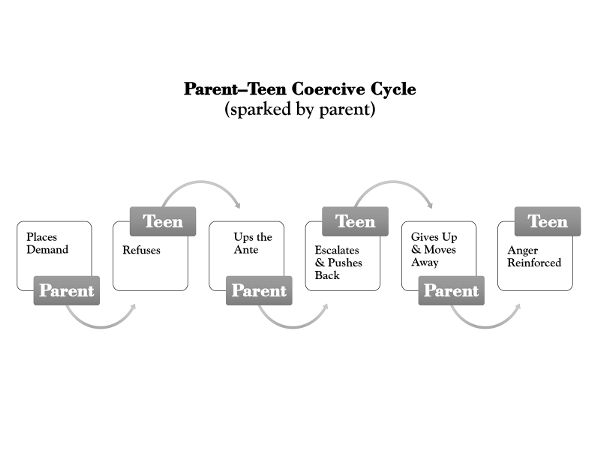

Gerald Patterson (1982) and colleagues at the University of Oregon coined the term parent–child coercive cycle to describe the pattern in which parent and child mutually influence each other in subtle ways to increase the stuck quality of their interactions and erode communication. Studies ranging over thirty years link these cycles to increased risk of behavioral problems in youth (Granic and Patterson 2006).

Consider this example: a seventeen-year-old named Jason sprawls on his bed, his fingers flying across his smartphone as he texts his friends. Dirty laundry is strewn about the room, all in the exact same spots where he’d peeled the clothes off, in some cases two weeks prior. His father enters the room and is struck by the stale smell.

“I thought I told you to put all this laundry in the hamper. Is it too much to ask for you to listen to me for once?!”

Jason doesn’t say anything, but shakes his head and makes mimicking mouth movements while he continues to tap away at his phone.

“So you’re going to just ignore me again? Is that the deal?” the father yells. “I’ve had it with you, Jason. You have no respect for me or for yourself by tossing your nasty clothes around like this.”

Jason looks up from his phone and glares. “Get the fuck out of my room! I’ve had it with you, too. You have no fucking clue what respect means anyway!”

The father walks to a pair of jeans, picks them up, and angrily throws them into the hamper. “Wow! You’re right, that’s such a chore!” he yells and walks out of the room.

Jason flips the middle finger at his father’s back and returns to texting, shaking his head with an indignant expression on his face.

How familiar is this example for you? In this instance, the parent initiated the sequence by presenting a demand (to pick up dirty laundry). But the teen can also be the one who presents a request or demand that sparks this cycle (see figures 1.1 and 1.2 below for a breakdown of the cycle in both situations). In coercive cycles like this one, parent and teen both punish and reinforce each other. Punish and reinforce are technical terms in psychology that describe how responses to behavior either make a behavior more likely in the future by being rewarding (reinforcement) or less likely by being aversive (punishment).

What’s happening here is a process of mutual triggering. The teen’s anger increases, punishing the parent. This continues until the parent’s demand, which is aversive and punishing for the teen, is either removed or the parent gives the teen what the teen wants. If the parent drops the subject, this reinforces and thereby increases the teen’s angry behavior. If the parent gives the teen what the teen wants, this reinforces the parent’s giving-in behavior, making it more likely in the future.

As a result of all this mutual punishing and reinforcing, cycles can feel hopelessly deadlocked. Communication breaks down as both parents’ and teens’ valid perspectives and needs are lost in the shuffle. In the example above, the parent has a valid need for cleanliness in the family home, as well as respect from his child. The teen has a valid need for his own space, into which his parent can’t intrude at will. Neither is able to appreciate the other’s needs.

With each repetition of the cycle, resentment, pain, anger, and the cycle itself solidify further. What you need are tools to interrupt these cycles and slow down the activity in the brain. This will give you—and your teen—a chance to sidestep anger, to start communicating directly, and to connect. It’s here that the PURE method (presented below), with its focus on mindfulness and positive psychology skills, can help.

What Is Mindfulness and How Does It Help?

The word mindfulness gets tossed about a lot these days, but what exactly is mindfulness? Let’s start by defining what mindfulness is not:

- Mindfulness does not require sitting on special cushions, wearing maroon robes, or going on retreats.

- Mindfulness may feel spiritual, but it doesn’t have to be.

- Mindfulness doesn’t mean becoming passive or a pushover. You can be very active, direct, and assertive and be mindful.

- Mindfulness is definitely not numbing or shutting off your thoughts and feelings. Rather, mindfulness involves actually staying very much in contact with what’s happening, but in a more flexible way. This is crucial for building better communication with your teen.

Noted mindfulness author and teacher Jon Kabat-Zinn defines mindfulness as “the awareness that arises by paying attention on purpose in the present moment and non-judgmentally.” (2013: xxxv)

That’s it. Sounds simple, right? It is. It’s also an extremely difficult way to consistently live.

But You Already Know Mindfulness

Mindfulness is not new to you, even in your parenting of this now-teenager. You were perhaps mindful when your child was born, or, if adopted, first came into your arms. You may have been mindful when beholding an amazing sunset, or when you met the eyes of a loved one after a gift that left you breathless, or when you felt the basketball in your hand and nothing else. What is new is your willingness to cultivate mindfulness as a set of skills for communicating effectively with your teen. Your intention toward greater and greater mindfulness in your relationship will lead to changes.

A growing body of research links mindfulness skills in parenting to positive outcomes in the relationship between parent and child. In one study, a mindfulness-based family intervention was shown to improve family functioning and reduce the potential for child abuse in comparison to a control condition (Dawe and Harnett 2007). A randomized trial with early adolescent youth that tested a mindful parenting program demonstrated improved child behavior outcomes, as well as improved parent–youth relationship qualities (Duncan, Coatsworth, and Greenberg 2009).

The research is clear: when adults and kids learn to become present with their senses and thoughts—to practice mindfulness—the negative effects of stress on health decrease; attention and concentration improve; ruminative thinking, low moods, and anxiety decrease; and well-being rises (Brown and Ryan 2003). Isn’t that motivation enough to start digging into these skills with your teen?

Ask Abblett

Q: So is the take-home message that I need to become a Buddhist and things will improve with my daughter?

A: Mindfulness is certainly at the center of Buddhism, as it is for Hinduism and Taoism—and, for that matter, many athletic endeavors. Mindfulness is not about religion or any form of worship. Mindfulness is about building a reverence for the present moment, about becoming aware of what is, and doing so with flexibility and nonjudgment. Mindfulness will bring you out of rigid thinking and unhelpful reflexive reactions to help you forge new pathways of connection with your daughter.

So how does mindfulness work to help you parent your teen? Well, in three ways:

- Mindfulness helps you stay in the present moment. By keeping your attention centered on a chosen object (such as your breath) and bringing it back to that object when distracted, you build the muscle of concentration in your brain. This trains your mind to stay in the present moment, rather like training a dog to stay.

- Mindfulness gives you insight into your own thought patterns. By noticing and labeling where your mind goes during mindfulness practice, you start to know your mind better, to learn its triggers, patterns, and habits. These insights help you prepare for situations that can trigger an avalanche of reactions when communicating with your teen.

- Mindfulness helps you be less judgmental. By being gentle and kind to yourself when your mind wanders off during mindfulness practice, you create a new habit of being compassionate with yourself. Being compassionate with ourselves is not something most of us are in the habit of doing, especially when things are stressful and going awry with our children.

Throughout this book, you’ll learn how to be more mindful of the things you see, touch, hear, taste, and smell, as well as of the words and images you hold in your mind. We’ll practice skills that not only build mindfulness to make interactions more fun and enjoyable, but also help you to connect with what’s really happening for your teen, inside and out.

Most people, most of the time—especially when angry—focus on stressful events from the past or future stressors on the horizon. This is particularly true for parents with regard to their children. Such mental time travel away from the present is a big part of what causes us to suffer. A wise supervisor once told me that all our suffering boils down to one statement we buy into without hesitation: “It shouldn’t be this way.” It’s on adults to help teens learn to get out of their heads and into what’s actually going on—to learn how to ride out the challenges and embrace what’s awesome.

In many ways, mindfulness is embedded within the idea of presence. And when you put all of your awareness and attention on what’s happening right now in your experience of your senses, healthy choices and actions become more likely. Presence is thus the first step toward addressing the communication breakdown with your teen.

Are you willing to learn to harness the power of the present moments of your relationship with your teen? In the end, these moments are all we have. The stories we tell ourselves—our imagined narratives of past and future—pale in comparison to what we have when we claim moments in mindfulness. How about claiming them with your child?

What Positive Psychology Brings to the Table

In addition to mindfulness, this book introduces you to what the science of positive psychology has to offer your relationship with your struggling teenager.

When I first heard the term positive psychology toward the end of my training years, it conjured up searches for rainbows and unicorns. This new happy-focused branch of my field seemed a little light on substance and a little heavy on affirmations.

I was wrong. Positive psychology, or the study of the how of happiness, is hard science, and it has shown that we’ve been approaching some things backwards for a long time. When it comes to happiness, we’ve been conditioned to think we must do, be, and acquire many things to demonstrate we’re successful, and then we’ll be happy. What research in positive psychology shows is the reverse: that when we do, be, and acquire happiness-related thoughts, feelings, and actions, success tends to follow (Seligman 2002; Achor 2010).

Positive psychology studies how we can generate perspective, inner (emotional and cognitive) and outer (behavioral) flexibility, and excellence in our daily pursuits. Positive psychology is about finding flow in our work and relationships (Csikszentmihalyi 1998) and developing a growth mindset for facing life’s challenges (Dweck 2006). It’s about consciously cultivating your social support network (Uchino 2004) and spreading goodwill to others in a way that amps up your own well-being and effectiveness (Biswas-Diener, Kashdan, and Minhas 2011). Positive psychology teaches us to guide our mindset, emotions, and behavior in order to build life satisfaction ourselves instead of waiting around and hoping that the bluebird of happiness will magically land on our heads. Positive psychology’s practices are powerful antidotes to the toxic experience of unchecked anger.

That’s why I’ve built mindfulness and positive psychology into this book. These practices help get at what’s hardest about managing things with your teen—and they do so without increasing worry or pessimism or labeling your teen as conduct disordered. While it’s important not to bury our heads in the sand about disruptive and debilitating conditions, it’s also not helpful to anyone to have diagnoses, syndromes, and disease entities be the sole focus of the field dedicating itself to improving the mental and emotional circumstances of an entire society. One of the primary skills from positive psychology you’ll practice is shifting your frame for understanding your teen’s behavior.

Findings from positive psychology include:

- Developing self-control in one area of your life leads to greater self-control in others (Baumeister and Tierney 2012).

- Creating a daily habit of tracking reasons for being grateful leads to increased optimism and effectiveness in performance situations (Achor 2010).

- Inventing positive counterfacts, or a positive explanatory style, after a difficult experience leads to increased ability to successfully cope with challenges (Seligman 2006).

- Playing to one’s strengths significantly increases well-being and performance at work (Linley 2008).

These findings are just a brief sample. Throughout the book we’ll explore how perspectives and skills that draw on positive psychology can improve your situation with your teen.

Now let’s turn to the key underlying structure of this book: the PURE method of communication.

The PURE Method of Dealing with Communication Breakdowns

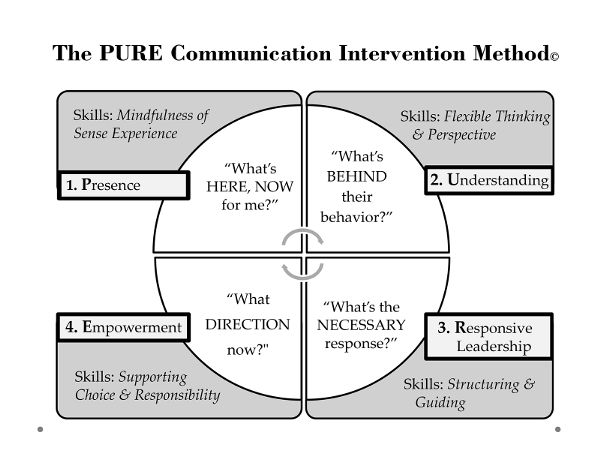

The PURE method of communication is built around a set of skills that, taken together, can help you break the stalemate between you and your angry teen and allow you to parent with a lot less conflict:

- Presence or a mindfulness of sense experience

- Understanding or a mindfulness of thoughts paired with compassionate perspective-taking

- Responsive leadership or leading interactions forward with clear, consistent communication

- Empowerment or affirming autonomy and choice regardless of the situation

Figure 1.3 shows our roadmap for this book. The PURE method is best thought of as a series of steps that represent the ideal responses for parents when teens are struggling.

While this sequence of communication moves is ideal, it is not an immediate cure for all of the problems occurring in your relationship with your teen. If you’re reading this book, things have likely built into a “toxic” or stuck state over time. It will take time to “purify” the communication, to enhance the relationship and reduce the problems for your teen. A filter doesn’t immediately transform sewage into pure drinking water. Sewage water needs to flow through the filter for some time before it becomes purified.

Figure 1.3: The PURE Communication Intervention Method

Figure 1.3: The PURE Communication Intervention Method

A core principle of the PURE method of communication is that parents must practice presence at the start of any challenging parenting situation. Again, presence here is a mindfulness of sensation and emotion that allows for balanced, flexible responses. Even if a parent merely takes a short mindful pause, the parent’s next action to communicate with an angry teen will be much more likely to be effective. We’ll spend the next chapter learning and practicing such skills of presence so that you can nonjudgmentally hold the experience rather than react in kneejerk fashion. Not only must a parent start with presence, the parent must carry mindfulness forward through the rest of the interaction.

Once firmly established in present-moment awareness, the parent can then turn to the second step: seeking to understand what lies behind the teen’s angry and disruptive behavior. This requires sidestepping biased, rigid thinking. What is it that’s most real for your teen that makes these actions so urgent? That’s perhaps protecting the teen in some way? The goal here is for parents to learn the habit of curiosity about the inner experience of their teen. By communicating this curiosity, parents show that they are willing to hold not only their own reactions, but want to help teens hold their own as well.

After understanding comes a crossroads moment. This is when your teen is expecting a lecture, reprimand, or perhaps a cold shoulder from you. Your teen may also be expecting confusion, distress, or downright despair. With responsive leadership, parents learn to do and show the opposite. Instead of moving too forcefully in or pulling too far away, parents mindfully lean in and lead the teen with support, structure, and guidance. Again, parents move to this third step of the PURE method with presence and understanding already tucked under their arms.

The interaction—and an entire interaction may take only twenty seconds or less—ends with an empowerment move. The parent offers a supportive reminder that the teen gets to choose what happens in their own mind and behavior, and that a parent can’t dictate those things. The parent speaks from the heart and lets the teen know what truly matters, including that the parent notices even the smallest positive efforts. At this point, parents should also quietly give themselves kudos for doing all they can to communicate their loving, supportive intentions despite a difficult interaction.

It’s the rare teen who at this point suddenly looks up, anger melting with peaceful relief, and says: “Why thank you, Mom or Dad! I appreciate you validating my feelings and giving me support and guidance despite my ranting and swearing! Very kind of you!” (You’d probably spontaneously combust in disbelief if your teen did this anyway.)

What does happen, though, is that after multiple PURE cycles your teen will begin to trust that a different pattern of communication with you is not only possible, it’s already happening. Things will feel better. The overall energy will shift toward solutions and connection and away from breakdown and lashing out.

Let’s return to the example from my practice of the fourteen-year-old and his mom. In the moment after the boy threatens to trigger a breakup between his mom and her boyfriend, the mom could choose to try a PURE communication cycle.

- Presence: The mom breathes in, fully notices the sensations in her body, and gently labels them with the thought, Anger is here. She breathes into these sensations and notices space around them.

- Understanding: The mom notices that she is having the thought to tell him he’s a little ass and is going to spend the summer in a residential program if he doesn’t cut it out. She looks up at her son, his face warped with disgust, and she looks past the disgust for another breath’s worth of pausing. She wonders about the pain there for him. The pain they’ve not talked about in months. She talks slowly and with a lightness in her face as she looks at him. “I really have underestimated how hard it’s been for you with me dating Dan these past few months. I can see how it would feel easier if he weren’t around to complicate things and pull my attention away from you.”

- Responsive Leadership: The teen rolls his eyes, but does not lash out again. His anger seems to have stalled. The mom leans in toward her son, her voice somehow softer and yet more urgent. “I want to quit missing what’s important for you. It’s on me that I haven’t been there to really listen, and I’m sorry for that. It’s important for us to respect each other. I need to listen and I need you to work on talking more respectfully to me. I’m hoping we can work on this together.”

- Empowerment: The boy looks at his mom. Disbelief and mistrust are stamped on his face. “Yeah right,” he mutters. The mom breathes again, maintaining presence and reconnecting with the understanding of what’s behind his behavior. “It’s up to you if you want to work on your piece, just as much as it’s up to me to be responsible for mine. I’m up for it if you are. Actually, I’m up for it even if you’re not ready to. I can’t make you choose.”

Yes, this is an ideal set of PURE responses from the mother. And yes, though you will stumble many times (I still do!), this sort of communication is possible for you. As we’ll see, it’s not about being a tree-hugging pacifist in the face of threats and risky behavior from your teen. You will set limits on your teen’s behavior, but you’ll do so with much greater internal and external flexibility. You’ll have more options open to you, and your teen will be much more likely to experience you as compassionate and caring.

Now, let’s get on the path of practice.

Basics of Mindfulness

When we practice mindfulness, whether for a few seconds or longer, we simply rest our mind on something in the present moment. We can do this either by concentrating on a specific anchor, such as the sensations of our breathing, or by noticing whatever is happening in our senses with full, nonjudgmental attention from moment to moment—what we can call open awareness. Whether through concentration or open awareness, mindfulness helps us realize how our minds habitually race to the past or future, while our bodies and five senses exist only here in the present. When our mind wanders, we notice where it has gone, and our mindfulness skills gently bring our mind back to experiencing the here and now. Again, notice that mindfulness involves three parts: intentional attention, being present in the moment, and acceptance/nonjudgment. “Presence,” as I use it in the PURE method, is mindfulness of what’s showing up in one’s physical senses in a given moment.

Throughout the book, we’ll explore various activities to help you develop mindful presence. Remember, mindfulness skills are a crucial first step to transforming communication breakdowns with your teen. Without this foundation, little else will work, and breakdowns will continue.

Let’s begin with a couple of quick activities that demonstrate the power of presence. They are also excellent tools for grounding yourself in the here and now. I recommend returning to them frequently.

Skill Practice: Sounds Around

- Wherever you are, pause what you’re doing.

- Take a slow breath in and out through the nose.

- Gently close your eyes.

- Start to notice the sounds arising around you, beginning with those nearby and extending to the more subtle sounds in the distance.

- Without judging or analyzing the sounds, collect the sounds as they come, silently counting them with your fingers.

- If you become distracted by thoughts, gently return to collecting the sounds around you.

- Once you’ve collected a sound for each of your fingers, open your eyes.

Notice that the sounds came to you, that you didn’t have to search with your attention to find them. How might you allow the sounds of your relationship with your teen to come to you, rather than going out in search of the next conversation or argument?

A key aspect of mindfulness is trusting your awareness of what is in the moment over what your thoughts yell at you to do or say—or not do or not say. Of course, you need to think when you’re interacting with your teen. As you build mindfulness skills, you’ll begin to notice whether all this thinking really helps you to help your teen. Have you been able to think your way into a connected relationship with your teen?

Let’s try a mindfulness practice focused on sensations of breath and body movement.

Skill Practice: Whiffs of Wakefulness

This is a great activity for developing awareness of your breathing, waking yourself up, and relaxing your entire body. Pure heaven for the tapped-out parent of a teen!

- Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart. Feel your feet grounded on the floor; feel a strong sense of being rooted there, as if your feet were growing deep into the earth below.

- With eyes open, begin to inhale slowly and deeply through the nose. As you do, gently raise both hands back and out to the sides, as if you’re embracing the sky. Gently arch backward, so that you’re looking upward.

- Exhale slowly from the mouth. As you do, slowly fold yourself forward and down. Imagine that your body is a bellows and you are slowly squeezing all the air from your lungs. Continue to fold forward until your arms dangle down toward your feet and all your breath has been expelled.

- Repeat the process: inhale, arching your back and opening your arms out, then exhale, folding in and bending down.

- Continue for several cycles.

- Stand upright, your hands loose at your sides. Close your eyes. Notice how your body feels. Notice any tingling, any energy moving in your body. Notice how your mind has shifted during this practice.

Basics of Positive Psychology

Now let’s start building the positive infrastructure that will help shift your communication with your teen. Here are two short practices that will help you cultivate clarity and change in your parenting.

Skill Practice: Parental Power Questions

Research is clear: our perspective on events—our mindset or frame for what’s happening—is crucial to the sorts of outcomes we experience. A study by Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck (2006), on growth or flexible mindsets versus fixed or rigid mindsets, found that children and adults who adopt a growth mindset fare much better with regard to grades, productivity, and the like than those who adopt a fixed mindset.

In this practice, you’ll apply a growth perspective to your parenting. Remember, even though things may have seemed stuck for some time, that can be changed.

- Consider a recent communication with your teen that seemed to hit a dead end.

- Finish the following sentence: “When it comes to addressing this situation I .”

- If you finished the sentence with anything like, “have thrown up my hands,” or, “have tried everything and don’t have a clue what to try next,” or, “think it’s really my kid’s fault,” then try the following:

- With your eyes closed, visualize your teen’s appearance and behavior during the communication breakdown. Set aside any rigid mental chatter and consider the following power questions:

- What am I willing to give my teen right now so that my teen sees how much I want to help us out of this situation?

- What’s more important to do in the next moment: venting and reacting, or doing and saying what matters most?

- What am I willing to risk in myself in order for my teen to see how much I care about connecting?

- Imagine what might happen next if you acted from one of these internal power questions. Would it be the same breakdown as usual, or might there be some space for growth?

Let’s wind down now with a core practice to build your overall skills in mindfulness and positive self-management.

Peaceful Parent Practice: WHEN Is My Mind?

This practice focuses on what I refer to as offline skills. These skills, spread throughout the book, are offline in the sense that they are meant to be practiced when you have the time and space to do so, not in the moment when things are difficult with your teen. These core practices lay a foundation that supports your own well-being and helps you hang in there. Think of offline practice as similar to going to the gym to get fit—you have to keep showing up to achieve the results you want.

In a quiet space, take a few minutes to practice the following:

- Sit in an upright, alert posture with your eyes closed.

- Settle in. Take a couple of deep, centering breaths.

- Step into a timeless machine. This is the opposite of a time machine. The timeless machine doesn’t move you backward or forward in time; it erases time altogether—there’s only the present moment.

- Consider: When, as a parent, have you experienced a sense of time falling away? When have you been so engaged, focused, and aware that you became lost in whatever it was you were doing?

- Don’t analyze or judge whatever emerges. Just notice and experience it, no matter how mundane or magnificent it may seem.

- Take another deep, full breath. Quietly continue to notice your thoughts and feelings about this activity.

The timeless machine shows you what you do—or have done—as a parent that is so engaging that you lose track of time. These are the activities and interactions that you just flow into. Once you’re doing them, things groove and thoughts go quiet. Even if you’re exhausted by your teen’s anger these days, consider: what are the timeless things you do with your teen, or for your teen, that you don’t have to be convinced to do?

For me, one of these timeless things is making a silly duck voice so that my toddler Theo giggles uncontrollably. Another is having car chats with my kindergartener Celia. In one recent car chat Celia informed me that “the other cars can’t hear you yelling—they’ll move out of our way on their own.” (Who’s teaching mindfulness to whom?)

The point here is to pause amidst all the stress and remember that connection is most likely to happen when past and future drop away and there’s only the now of sharing. These timeless moments are what parenting should be about.

Practice noticing these moments—sometimes small, sometimes large. Don’t let them mindlessly slide past your awareness. Note them, be in them. Savor their sights and sounds. Record the experiences—jot them down in a journal, the margin of this book, somewhere. When you’re with your teen, practice noticing these timeless moments on a regular basis. You’ll be astounded by what you would have otherwise missed.

These moments can become the basis for you to connect in a more authentic way with your teen. This practice of noticing can break you free of blinders and help you see possibilities for positive change.

And here’s what’s really great: most teens will notice you noticing them. When you practice this strategy you send a powerful message of curiosity and openness. Both are important in establishing new patterns of communication and connection with your teen.

Your Parental Agenda

Before you move on to the next chapter:

Review the RSVP needs that typically underlie anger in teens. Explore in your journal how these might be relevant for your teen.

Consider the clinical factors that can contribute to anger; investigate consulting a licensed mental health professional, particularly one specializing in clinical work with adolescents.

Try to identify coercive cycles that may be operating between you and your teen. How may practicing the PURE method of communication benefit your situation?

Journal honestly about your intentions in working through this book. Are you merely looking to get your child to behave, or are you willing to work on the overall health of your relationship?

Practice the mindfulness and positive psychology exercises with an attitude of patience and openness.

Figure 1.1: Parent–Teen Coercive Cycle (sparked by parent)

Figure 1.1: Parent–Teen Coercive Cycle (sparked by parent) Figure 1.2: Parent–Teen Coercive Cycle (sparked by teen)

Figure 1.2: Parent–Teen Coercive Cycle (sparked by teen)