3

Understanding: Creating Clarity in the Cycle of Teen Anger

You can practice mindfulness meditation in a cave in the Himalayas for decades, but if you don’t develop your capacity to understand your teen’s suffering, your ability to change your reactions in the face of your teen’s anger will be limited. This chapter stands firmly on the foundation of mindful presence to teach you to look “behind” your teen’s angry behavior with the compassion your relationship requires.

In this chapter you will:

- Build your willingness and skill to draw on the values that fuel you as a parent, even in the face of significant difficulty.

- Engage in practices designed to create flexibility in your perspective regarding your teen and yourself.

- Enhance your willingness and skill to emotionally tune into your teen, particularly when your relationship feels far from close or collaborative.

The Core Question: Are You Willing?

Near a monastery in the forests of Thailand grows a tree bearing a plaque. The plaque reads: “If you have something bad smelling in your pocket, wherever you go it will smell bad. Don’t blame it on the place.” The monastery’s abbot, Ajahn Chah, may not have been thinking of modern Western parents when he said this, but the wisdom applies just the same.

When faced with an angry or out-of-control teenager, it’s very easy to blame the “smell” of things on the badness coming from the teen. But we, as parents, bring our bad smells with us as well. This chapter focuses on learning to see both what’s good and what’s not so good in our own internal inventories as parents, as well as what’s happening behind an angry teen’s behavior. Clearly seeing patterns that help and hinder communication is crucial to helping your child.

I’m reminded of a baseball game and a parent and teen I worked with some years ago. It’s an example where teen anger and parental patterns—and therapist’s patterns, too—were all heavily involved.

From the bleachers I watched my school’s angry heavy hitter come to the plate. “Swing away, Russ,” his coach called. In the time I’d known Russell, I’d never heard anyone, not even his mom, call him “Russ.” In a few months that coach had gotten closer than I had in three years of intensive work.

As I took in the family onlookers around me, I found myself thinking that none of these people—including his coach—had any concept of Russell’s true behavior. They didn’t know Russell’s angry outbursts, they didn’t know how Russell would get in others’ faces, swearing with fists raised. They only saw a kid doing his best to assume the proper stance, trying to connect with the ball. I knew the truth.

There was no sign of Russell’s mom. By the fourth inning it was safe to say she wasn’t coming. She’d had enough of Russell’s tantrums at home, the threats and holes in her walls. Russell’s unsafe behavior and his mom’s inability to monitor him had led me to recommend Russell be placed in a residential therapeutic program.

While it was true that Russell’s neighborhood BB gun wars and angry battles with his mom were toxic and potentially dangerous, it was also true that my motivations for recommending the residential program were mixed. As T.S. Eliot writes, the “last temptation is the greatest treason: to do the right deed for the wrong reason.” I hadn’t been able to stand the anxiety and helplessness Russell’s intensity triggered in me.

Here was a teen looking to pin adults’ attention to him with the force of his fury. And here were the teen’s mother and therapist, each acting out familiar scripts of ducking and covering, of avoiding Russell’s intensity.

Working with Russell—and others in my caseload—almost led me to quit and slink away, away from the difficult situations, away from the anger pointed daggerlike in my direction. Thankfully, I’ve improved my ability to stay with my emotional discomfort when working with clients’ challenging behavior. I’ve grown, thanks to considerable practice of skills such as those in this book, as well as to support from others. My old pattern of avoiding others’ anger still tugs at me, but I no longer reactively follow it as often. Emotional patterns don’t go away, not for any of us. Rather, we must turn and face them with awareness.

I used to have a picture of a high-jump skier tacked to the wall of my office. Even before Sheryl Sandberg had made the phrase famous in her book of the same name, I captioned the picture on my wall, “Lean in.” When clients or colleagues in my office were facing an emotional challenge and their patterns tugged at them to turn away or push back reactively, I suggested they lean in. In order to lean into something difficult—such as taking a brutally honest look at your own internal stories and patterns that may be getting in the way of improving your relationship with your teen—it’s crucial to ask yourself a simple question: am I willing?

Identifying Your True North as a Parent

As you work through this book, as you do your best to help your teenager resolve anger-related problems, you will often feel lost and unsure of yourself. Part of the second step of the PURE method—understanding—comes from creating clarity as to what drives you as a parent. Becoming clear on what matters most for you will deepen your role as a relational leader for your teen. The core values behind your decisions as a parent—including your missteps—can help pull you forward and answer yes to the willingness question. After you’ve worked to identify these values and make them accessible, in challenging moments they can become a sort of magnetic north, offering you guidance.

To help you identify the values that give your parenting direction, let’s take a quick detour from parenting and go back to school.

Skill Practice: Your Greatest Teacher

- Sit in a quiet place and close your eyes. Take a breath and remember how your breathing has always been there inside and around you. Your breath is your constant companion, there to help your body adjust to whatever the situation requires.

- When you were a kid in school, there was a teacher who really mattered to you. A teacher you most admired. A teacher who had the greatest positive impact on you. Let your mind gravitate toward this teacher. Imagine this person clearly, using multiple senses. Remember exactly what the teacher did or said that hit the mark for you.

- What, specifically, were this teacher’s actions toward you? What qualities kept showing up in the teacher’s teaching and interactions? Don’t just think about it—allow yourself to really feel your answers as they show up.

- Open your eyes. Note these specific actions and qualities in your journal. Write down as many things as possible that made this teacher special for you.

- Pause for a moment and notice how you feel. What’s showing up for you as you remember this teacher? To what degree did you want to perform well for this person? To what degree did you want to be in this person’s presence? How much did you end up learning?

- Notice the qualities you listed in step 4. How important are these for you to embody in your role as a parent? If they’re important to you and you embody them, what might be the impact on your teen?

- Consider embracing your teacher’s qualities as guiding values for you as a parent. You are not your teen’s formal educator, but you are the teacher your teen will learn from the most.

We’re working here to identify and create more ready avenues for you to access these values. No one and no book can create these values for you—they are already there. If you are willing to understand what they have to show you, these values are ready to guide you. Authenticity, compassion, perseverance, generosity—whatever they are, you need only be willing to let yourself move toward them when opportunities arise.

A Chinese proverb tells us, “Pearls don’t lie on the seashore. If you want one, you must dive for it.” Living our values entails taking a risk. We risk the pain of falling short in our parenting. But if we don’t take that risk, we’ll have nothing of true value to pass along to our children. Let’s turn now to another values-clarification exercise, this time focusing specifically on your teen.

Skill Practice: Your Teen’s Commencement Speech

- Close your eyes and imagine that you’re sitting in a huge auditorium. It’s graduation day for your teen. Hundreds of people sit in bleachers all around you.

- This ceremony has a unique importance for you: your teen is delivering one of the commencement speeches. Your teen approaches the lectern and looks straight at you.

- Your teen speaks from the heart about your actions and who you are as a person—the things that have mattered that helped your teen get to this important day. Visualize this scene in as much detail as possible. Ask yourself, What do you want your child to say? What do you, in your deepest heart, want to hear your teen say about what you did that mattered—and perhaps to you too?

- Whatever actions or qualities you’ve imagined your teen talking about—and no one can tell you what they are; again, they are part of who you are—list them in a journal or on a piece of paper. Focus on actions or qualities you can do in an ongoing way, such as “being engaged,” or, “giving support,” or, “championing my teen’s dreams.” Focus less on individual outcomes, such as “taught my teen to drive a car,” or, “got my teen into a good college.” It’s the ongoing things you most want to hear about, right? The things you were doing regularly that really mattered. These actions and qualities serve as directions that are always there to guide you as a parent.

Note that these are not goals, not things you check off your to-do list so you can move on. They’re things you keep showing up to do and that you do simply because they matter. These are true directions, like headings on a compass. You’re never really done with these; rather, you just keep moving in these directions. Are you willing to let your values emerge as clearly as your teen’s voice at commencement?

Skill Practice: Forget Silver Linings—Go for Gold with Your Teen

Positive psychology research consistently shows that cultivating feelings of gratitude leads to positive outcomes in well-being and happiness. Here, we will begin a practice you can return to regularly to cultivate this attitude with regard to your relationship with your teen. This practice also serves to help you continue to clarify the values underlying your parenting.

- Consider a specific way or situation in which things are blocked or broken down with your teen. Think about what seems to always get missed or misunderstood. Look at the moment when things seem to go awry.

- People have probably suggested you find the silver lining when things are hard. “Oh, at least you have your health,” or, “But look at how smart your kid is—Harvard-bound for sure,” or, “No one can have it all, just think about everything else in your life that’s working so well.” Forget all that. Discard all these warm and fuzzy distractions. Instead, lean your attention directly into the communication breakdown with your teen.

- Ask yourself: How is this situation with my teen a gift to the parent inside I most want to embody? Core feelings and needs drive things to get stuck between you and your teen. This stuckness is a gift, a wake-up call to help you establish a meaningful and lasting connection.

- Are you willing to view this situation as a gift? A growth mindset asks you to consider that change is possible and will come—even if you can’t see how or when just yet—particularly if you’re willing to approach breakdowns with an attitude of gratitude. Try it: hold this breakdown in a moment of felt gratitude. Might your teen notice this shift in your perspective? What impact might this have?

No skier goes over the lip of a ramp (Olympic ramps are 394 feet in elevation!) without at least a moment of willingness. No one shoves a skier over the edge. And no one can make you look deeply into your own emotional patterns. That’s why this chapter asks you to pause and really consider the question: Are you willing? Are you? It’s fine if you say no, just know that this may carry some costs. It’s to these costs we will turn next.

Q: How does identifying my parental values help when my kid is out of control?

A: Identifying your values is not an intellectual exercise that gives you insights or solutions. Knowing your values, however, gives you an emotional nudge toward what matters most, even in the heat of the moment with your kid. Your values show you your highest self as a parent. Being able to identify and focus on them can help steady you as you progress through the methods of this book.

The Costs of Miscommunication

In chapter 1 we discussed how our brain’s anatomy makes anger and reactivity universal, even though these often get in our way. But there’s more to the story than just the firing of neurons in the brains of parents and kids. Part of what leads everyone involved to feel hopeless and stuck is a pattern of communication that tends to build up over time.

As we also discussed in chapter 1, coercive cycles can build up between parents and kids through a process of mutual reinforcement and punishment. These coercive cycles are unplanned, and yet very destructive communication breakdowns between teens and parents. It’s the relationship here—not the teen, nor any power moves, oppositionality, or manipulation—that is the problem. Either the parent, the teen, or both can initiate the cycle, leading to increased anger and solidifying the negative pattern.

Consider this anonymous quote: “Your thoughts become your words. Words become your behavior. Behavior becomes your habits. Habits become your values. Values become your destiny.” Momentum can grow from the smallest of internal experiences. Untended, our thoughts can evolve into either the brightest or darkest aspects of our character. Over time, our thoughts coalesce into the emotional inheritances we pass on to our children.

Recently I worked with a mother of a teenaged girl who had significant learning, emotional, and behavioral challenges. The mom herself had struggled with mood-related difficulties throughout her life. Over the years, this mother and daughter had become increasingly entrenched in a destructive dance, with escalations taking the whole family hostage and threatening the well-being of siblings and the woman’s spouse.

“After that last explosion from her,” the mother said, “something snapped in me, or maybe more like died. Now, when she starts yelling, badgering her sister or bringing up awful things I’ve done in the past, I don’t lash out in anger like I used to.”

I told her this was good—being able to contain the anger and resentment her daughter’s behavior caused was a step in the right direction.

“The problem is,” she continued, “I don’t feel anything for her anymore. I just don’t care. So I just sit there and don’t react no matter what she does.”

What at first had sounded like an adaptive, healthy change was actually a serious turn for the worse. Yes, this mom no longer flared at her daughter, but at a cost—it was if she had died as a parent. And now this girl had to come home from school and watch her mom go on living with everyone but her.

“She can’t keep doing this to me,” the mother told me. “She keeps me on the hook for the mistakes I’ve made. But you can only allow yourself to be abused so many times before it’s time to leave. Divorces have to happen sometimes. Brutal bosses should expect victimized employees to quit.”

“You have to ask yourself,” I told her, “what will be the cost if things stay dead like they are? What will you lose that will matter a great deal? And are you okay with that?”

I was asking this mom to step aside from the resentment and self-protection that, understandably, had a stranglehold on her parental heart. I asked, “Are you able to just watch what your mind is doing right now?”

The goal of the exercise was for her to wander her way to something that resonated with her—something more important than her attempts to control and force away her pain.

I asked this mom to imagine her daughter was sitting in the empty chair across from her. “It’s the last chance you have to talk to her. She doesn’t know it, but you know you will die tomorrow. The how doesn’t matter, but you know it, with certainty.” I looked at her, pausing to allow this to settle in.

“It’s the last full breath of your life. What will you say?”

All parents—this mother and myself included—build up expectations, assumptions, and judgments based on what our kids and the contexts we live in bring us. Our feelings of being overwhelmed can blind us to possible pathways forward with our teens. Rigid thoughts inside can feel more real than the teen actually standing in front of us, face pained and desperately hoping.

Truth was, this mother was waiting to feel differently before she would change her actions. She was doing what many of us do, particularly when we’ve been sufficiently burned in our relationships. We let a numbness of heart block us from doing anything to break the patterns that have generated so much momentum, thinking things like, I can’t reach out to them because I don’t feel like it.

Emotions often follow behavior. When we do things, feelings tend to trail along in their wake. Minds, because they are slow on the uptake, fool us into thinking the causal chain goes in the other direction. Depressed people wait for their mood to shift before they attempt to engage in life once again. Anxious folks wait for calm before they step out into the unknown. And overwhelmed, burned-out parents wait to feel connection again, to feel at least a flicker of compassion and caring before they reach out toward their “oppositional” teen.

What if the teens are waiting as well? Waiting for us to lead them away from this reactivity we’re silently yet powerfully passing on to them? They are our children, they have no choice but to be the heirs of our actions. Potentially, as parents themselves, they will have to consider what inheritance will go to their own children, and so on.

What if we, the deadened parents, were willing to ignore our numbed or resentful minds and move ourselves in the direction of our children? Would they notice the change, the shift in our patterns? What message might that send?

Remember, you did not choose your brain’s anatomical structure; the subtle, mutual shaping of a coercive cycle with your teen; or the genetic and learned inheritance of emotional patterns from your own parents. You did not choose the patterns in which you and your teen are ensnared. But you can learn to manage them responsibly. You can practice PURE communication methods for sidestepping old reactivity and finding new patterns, leading toward less anger and more connection with your teen.

Skill Practice: More Than Our Stories as Parents

- With something to write on, set a timer for one minute. In that time, as rapidly as possible, list as many positive attributes or qualities about yourself as a parent that you can.

- Set your timer for another minute. Do the same for your negative qualities as a parent. Again, write them down as quickly as you can.

- Close your eyes and take a few centering breaths; perhaps practice the 3+3=6 Math Breathing exercise from chapter 2.

- Open your eyes. Survey both lists. These lists basically summarize the story you tell yourself about your role as a parent. Notice how it feels to read your story.

- Ask yourself: Is this story sufficient? Does it fully describe who I am as a parent in every possible situation? Are there things left unaccounted for here?

This chapter teaches a deeper understanding of the inner narrative driving communication between you and your teen. Particularly in the tougher moments, you’ve likely been buying in to your inner story as if it’s absolute truth. You believe it with holy book intensity. We all fall into this tendency at various points. Check in with yourself about how things tend to go when you cling to your story too tightly, whether what you’re clinging to is the good stuff or the not-so-good stuff. Are you willing to loosen your mental and emotional grip on this narrative about yourself? What happens in your parenting when you do?

The Heirs of Our Actions: Emotional Patterns in Parenting

Psychologists (Gottman, Katz, and Hooven 1996) have introduced the concept of parental meta-emotional philosophy. Your parental meta-emotional philosophy is the accumulated set of feelings and thoughts you have about both your own emotions and the emotions of your children. Again, parents are their children’s greatest models of emotional and social competence. Parents play a major role in the emotional socialization of their children, helping them to label, understand, and manage emotions (Stettler and Katz 2014). Through both direct observation and modeling, parents’ emotional behaviors and expressiveness influence their children (Halberstadt, Crisp, and Eaton 1999). While children also learn indirectly from various emotion-eliciting social situations—for example, at school, in the neighborhood, during extracurricular activities—parental influence is often viewed as the most significant (Hakim-Larson et al. 2006).

Gottman and colleagues (1996) propose that what parents think and feel about emotions in themselves and their children—their parental meta-emotional philosophy—is related to how they shape emotion in their kids. This research highlights four styles of meta-emotional philosophy. The emotion coaching style involves adaptive parenting. Parents are both aware of feelings and actively help their children process their feelings, offering appropriate labels and validation, as well as guidance for managing them. The laissez-faire style similarly includes awareness and acceptance of children’s emotions; however, parents using this style are less likely to set limits or teach children how to resolve difficulties that arise. The dismissing style ignores and trivializes children’s negative emotions. Consequently, children get the message that they should disregard their own emotional experiences, which can lead to difficulties in learning to regulate their feelings. The disapproving style involves a similar lack of acceptance, but parents with this style also actively criticize their children’s displays of negative emotions, often punishing children for showing their feelings openly. This can create significant obstacles for these children with regard to accepting and managing their own emotional experiences, sometimes for years to come.

Science now links the patterns of managing and expressing emotion that children learn from their caregivers to later outcomes, sometimes extending much later into adulthood. Thus, for example, such patterns can affect future parenting practices (Gottman and Carrere 1999), increase self-soothing in children (Gottman, Katz, and Hooven 1996), yield more successful friendships and romantic relationships (Simpson et al. 2007), and contribute to the intergenerational transmission of abuse to subsequent generations (Duffy and Momirov 2000).

When it comes to understanding your emotional patterning, a great deal is at stake. There’s what happens with your teen’s anger in the immediate sense, and then there’s the patterning the teen will carry into the future as your emotional heir, and likely as a parent as well.

Understanding Your Own Emotional Patterning

As a kid, I loved my mom’s compassion—my mom was the closest thing in real life to June Cleaver from Leave It to Beaver—and it often helped me. But not on one particular day. That day I didn’t want to get out of her car. I wanted to quit Little League.

“You dropped it, Abblett!” The face of Mr. Pencher, my coach, always had the look of an impending aneurysm when he spoke to me. “You gotta get under it. Don’t be scared of it!” I hated him almost as much as I hated myself for how much I sucked at baseball. I just couldn’t get on top of the jitters I felt as I stepped up to the plate or watched a fly ball hang like a massive moth up in the lights until it quickly flew down at me. It’s not easy to see a ball with tears brimming.

In the car that day, I looked over at Mom and rammed my sweating palm deeper into my glove. “I want to go home,” I said. My mom tried to nudge me to stay, “Don’t you want to play with your friends?” But this only reminded me of how they would all shake their heads when I dropped yet another ball. Anxiety swelled. I turned on the tears. “No, don’t make me stay.” Before I knew it, I was homeward bound. Spider Man comics would be my faithful solace.

And so it went, across hundreds of situations: I would encounter something intimidating or upsetting and, if I pitched enough of a fit, my mom would smooth things over. I would get to sidestep the issue and move on. These interactions helped ingrain a pattern of avoidance in me.

Much later in my life, as clinical director of a therapeutic day school for children with emotional and behavioral issues, I would regularly witness kids in the midst of volcano-like tantrums or extreme states of agitation. I’ve seen kids swear, kick, spit, punch, break everything in sight. And I’ve seen those trying to care for these kids struggle with the emotional impact of their proximity to all this intensity. And then there was me: a guy from a household where anger and volatile emotion were to be avoided at all costs. Though it depended somewhat on the situation, anger and conflict were definitely taboo. I had developed a keen radar for conflict and had learned how to sidestep it before anger could spark.

You can imagine the challenges I experienced when I first began a job where conflict was a regular guest in my schedule. When I was paged because a child was in a significant behavioral crisis—screaming, crying, swearing, and yelling—my anxiety would surge and I would want nothing more than to walk—or run—in the other direction. This avoidance pattern was woefully unworkable.

We’re not after insight into the origin of these patterns or scripts here. It doesn’t matter much whether mommy or daddy did or didn’t do such and such, or what this might say about your tendencies toward lollipops or messy desktops. My old pattern of avoidance is not my mom’s fault. Indeed, such thinking is not only unhelpful, it helps maintain the pattern. Ask yourself, If I learned my unhelpful pattern from my parents, where did they learn it? Keep asking and you’ll find there’s no one person on the other end of the finger you’re pointing.

So what do we do about these patterns that block us in our parenting? Making progress on these patterns comes down to our willingness to get a full sense of the here-and-now impact of the pattern. To get a full sense of our willingness to understand what is happening now inside ourselves during interactions with family, to understand how our minds are molding the thoughts and emotions we experience in the present moment.

Skill Practice: Your Style of Managing Negative Emotions

In quiet meditation, ask yourself the following questions. Don’t sit analyzing your answers. Instead, gently and without judgment, notice what emerges in your thoughts and emotions as you slowly pose each question. You can pose just a single question for a given period of contemplation, or you can pose multiple questions and see how they influence one another. The point here is to cultivate a stance of compassionate curiosity as to the patterns that underlie your emotions, particularly the negative emotions sparked by the current situation with your teen.

- When you are sad or lonely, how do you tend to treat yourself?

- When fear builds inside you, what do you tell yourself about it? What do you feel you need to do?

- When restlessness and anxiety brim, how do you respond?

- When anger either swells inside you or is directed at you, what is your immediate inclination?

- When you are confused and feeling overwhelmed, what does your mind lead you toward? What do you end up doing?

- For any of the emotions above, in what direction are you pulled—toward them, away from them, or against them?

- Are you able to open to these experiences, or do you tend to close in some way? How do you close? How, specifically, might you open?

Next, take a moment and write the following blank table in your journal:

|

Open |

Close |

|

|

Sadness |

||

|

Fear |

||

|

Anger |

||

|

Anxiety |

||

|

Confusion |

Now, for each emotion, rate how willing you are to open to or move into painful sensations versus how much you tend to close down or move away from or against such sensations. It’s not that you should never close to emotional experiences. Indeed, sometimes, such as in the middle of an immense crisis, it can be helpful to do so in order to address the situation. Here, though, we’re interested in your general tendencies toward these emotions. The more closed your patterns are, the more work you’ll want to do to create flexibility, so that you can help your teen do so as well.

Q: After spending some time with this material on emotional patterning, I’m feeling pretty hopeless. How can I possibly do anything to sidestep this wave of reactivity that’s been carried across multiple generations in my family?

A: Instead of focusing on judging yourself and your family for these patterns, is there any room for compassion toward yourself? Toward your parents and grandparents? What would you say to a close friend struggling to come to terms with reactive patterns in their parenting?

Sticks and Stones: Understanding How Teen Behavior Affects the Parent

We’ve shed some light on patterns of emotionality that may be adding to the reactive mix for you and your teen. Now, let’s explore a tool for increasing your in-the-moment understanding of what is happening between you two and what you might do—in the PURE sense—to address it.

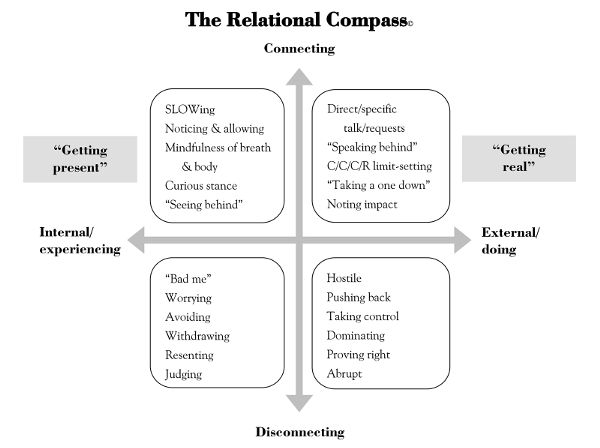

I created the following Relational Compass primarily to train therapists. But, in addition to being an excellent way to assess exchanges between therapists and clients, it’s also a great tool for assessing exchanges between parents and teens. The Relational Compass helps you take what you learned about your meta-emotional styles in the preceding contemplation exercises and put that into an interpersonal, here-and-now context. Do your habits of reaction to your teen—or anyone—lead you to connect or disconnect from the other person’s perspective and needs? Are these habits things you do in an external or observable sense, or are they internal, such as thoughts and feelings?

The Relational Compass helps you sort your habits into patterns so that you can start to use mindful understanding to catch them as they arise. Once you recognize your patterns, you can then apply your various skills of presence and understanding to create choice and flexibility in your responses. This can both break coercive cycles and help interactions move in a better, less angry direction.

Spend some time studying the Relational Compass. The top two quadrants include PURE skills with the familiar presence and understanding skills in the top left and responsive leadership and empowerment skills—which we’ll cover in the coming chapters—in the top right.

Now that you have a general sense of the Relational Compass, it’s time to start using it.

Skill Practice: Noticing the Pull Toward Unhelpful Reactivity

The following practice is meant to be used both offline and online with your teen. The goal is to use the Relational Compass to identify the specific situational and behavioral triggers that spark your unhelpful reactive patterns, beginning a coercive cycle.

Offline practice:

- Choose a recent conflict or anger-related situation with your teen.

- In a quiet location, practice a few minutes of mindful breathing as we’ve practiced throughout the book.

- With eyes closed, call to mind the episode with your teen. Imagine it in full sensory detail.

- Notice what’s happening around you—what’s said, what’s done, as well as things like time of day, who else is present, etc.

- Notice what’s happening in your thoughts and emotional reactions.

- Notice any impulses you may have to close down.

- Open your eyes. Using the Relational Compass as a categorizing tool, take a few minutes to review the episode, sorting both your reactions and your teen’s.

- Record what you have learned with regard to triggering factors and your own patterning in your journal.

Online practice:

- In the midst of a mild-to-moderate episode with your teen (for safety reasons, don’t practice this during the most severe episodes), notice any evidence in your body and thoughts that you are closing in a reactive, rigid, or rapid way. How are you flaring or fleeing—or experiencing the impulse to do so?

- If possible, remove yourself from the situation and sit for a few minutes.

- Work through steps 2 through 8 from the offline practice above.

- Give yourself credit for demonstrating sufficient PURE skills to notice your reactions and interrupt the pattern long enough to work on understanding it more fully!

Continue this sort of data collection across days and weeks if possible.

The more you assume the perspective of a curious observer of your own patterning, the more the patterns will shift in a positive direction. Sometimes, just looking helps detangle and loosen things. The next practice will help you set the stage for more helpful responses to your teen’s anger.

Skill Practice: Pushing at Unhelpful Patterns

This practice is adapted from the work of meditation teacher Ken McLeod. In Wake Up to Your Life (2002), McLeod writes of the value of learning to mindfully hold one’s reactive patterns—to use awareness to pause the mindless onslaught of our conditioning.

- Do steps 1 through 5 of the preceding offline practice sequence in order to establish mindful awareness of a visualized, yet real, exchange with your teen.

- Instead of just watching the cycle play out as usual, visualize yourself pushing on the pattern by doing something differently. Imagine yourself doing and saying something that opens you to the difficult aspects of the experience.

- Use mindfulness to simply notice and allow whatever shows up. Observe what happens in mind and body without judgment or labeling.

- Do not identify with the patterns. See the patterns as things that can change and shift like everything else. It’s not you doing them. They are doing you.

- Ask yourself: Are the original, closing, reactive patterns serving my values as a parent?

- Ask yourself: Are the imagined, new, open responses serving my values?

- Notice how you feel as you wrap up the exercise. Journal your observations.

In this chapter, we’ve identified how emotional patterning affects coercive cycles and miscommunication. We’ve practiced tools for recognizing and assessing these patterns as they show up in heated moments. Now, we will develop a key understanding skill: using mindfulness to shift how you relate to your own thinking—particularly thinking that keeps you on the treadmill of distress with your teen.

The Universal Errors in How We See Bad Behavior

When was the last time someone cut you off in traffic on purpose? When people do things that upset, displace, injure, or offend us, we often unthinkingly assume they intended to do it. I know I fall into this trap time and time again. Just a few weeks ago, a bus driver swerved into my lane, almost shoving me off the road. “He clearly saw me,” I said to myself. “What a jerk!”

Social psychologists have documented that humans tend to make a perceptual error called correspondence bias (Gilbert and Malone 1995). The essence of correspondence bias is the observer’s incorrect view of the actor’s control over circumstances. Correspondence bias leads us to assume that others’ behavior is a result of their internal traits and intentional choices—particularly with regard to negative behaviors like aggressive driving, substance abuse, or being irritable with coworkers. The human brain, in its role as observer, seems to take a mental shortcut. Instead of considering the many possible contextual factors that may have caused the behavior, be it another’s gestures, tone of voice, the influence of peers and family, or even the weather, our brain jumps ahead and shoves the behavior into a category: “He’s lazy, that’s why he didn’t turn in his homework.” “She’s an addict. Of course she destroyed her marriage.” This shortcut saves time and frees our brain to update our Facebook page or watch The Voice. Imagine how bogged down your mind would be if you always considered every nuance, every possible factor of others’ behavior. You’d end up snarled in your own mental traffic.

Ask yourself: What is the difference between the needs of kids at a cancer center and kids with significant emotional problems who throw tantrums? I believe the difference exists primarily in perception. Kids fighting cancer are, deservedly so, “empathy easy.” The kids I work with as a psychologist—and perhaps your teen as well—the kids who swear, kick, punch, refuse, and fail, are “empathy hard.” What’s crucial to understand, however, is these “unruly” kids are no less deserving of empathy.

In the years I’ve spent working with such kids, I’ve found myself prone to making certain assumptions. After a particularly dramatic display—f-bombs, middle fingers, whatever—I’ve caught myself entertaining phrases such as “attention-seeking,” “manipulative,” “oppositional,” or perhaps simply, “this kid is being a pain in the ass.” Sometimes I question such responses and realize I’ve fallen prey, again, to this universal yet reversible limitation of human perception. Our perspective as observers of others’ behavior can blind us. The same perceptual limitations get in the way of our parenting. The bad we see in our teen’s behavior can sometimes harden the very center of our hearts.

When looking at others, unless clear external factors leave the person blameless (such as the young child with cancer who did nothing to create the situation), we tend to assume that a behavior is the inevitable result of a person’s own internal traits. The person who cuts us off in traffic is a jerk. The colleague who walks out of the office in a huff has an attitude problem. They chose and therefore caused this behavior. It’s easy to see how our compassion—and consequently the efficacy of our communication—can then falter.

Distancing Yourself from Distorted Thinking About Your Teen

When faced with a teen’s anger, a torrent of thoughts run through the parental mind: Here we go again. I can’t believe she’s losing it over something so ridiculous! Why does she always have to do this. I’m so sick of walking on eggshells. She’s really manipulating the hell out of me. No way I’m letting her screw with me this time. (Add your own examples, perhaps plus an expletive or two.)

While these thoughts are completely understandable, particularly in the midst of an angry interaction, the emotional charge here suggests a problematic rigidity. The thoughts present themselves as real and accurate. They show a totally reasonable sense of unfair treatment at the hands of your teen. And they often imply an absolute aspect of time with words like “never” and “always.” While rigidity, truth assumptions, unfairness, and permanency may reflect the difficulty of the situation with your teen, how effective are you when you dwell on these qualities? Do thoughts infused with these characteristics help or hinder your ability to manage the moment?

An alternative is to build flexibility into how you relate to your own thoughts. Understanding requires a heaping helping of mindful awareness of thinking—of observing your own thoughts without either buying into them as absolute truth or trying to force them away. Try telling yourself not to think about how you’ve failed as a parent. Do it right now. Don’t let yourself think about it, not even a little bit! Pointless, right? You can’t force thoughts away, particularly ones with energy and momentum behind them.

What’s more helpful is to build your capacity to serve as a witness to your own thoughts. Can you notice yourself thinking right now? Pause and try it. Can you observe your own inner voice? The moment you try to do so, you are in understanding: you are mindful of your thoughts, instead of being the thoughts. Typically, when parents think about how they have failed, that thought feels very close, as if it’s inside them, part of who they are. Mindfulness helps you see the thought as merely a moment of information. It’s just a thought. Just one of the thousands your mind churns out on a daily basis.

Key to understanding is learning to watch your own thinking, to notice that thoughts come and go on their own. This sounds simple, yet takes considerable practice. Like bubbles you’ve blown, thoughts are just there: they float around a bit and eventually drift away and pop or disappear.

Skill Practice: Going BMW with Your Thoughts

Though I’ve never owned one, I’ve had occasion to drive a BMW sedan. It’s an experience that sucks you in; you can lose yourself in the desire to possess such a car. In contrast to BMWs, I’ve owned many thoughts over the course of my life. That is, I’ve regarded thoughts about my foibles, failures, and frustrations as being part of me. However, I’ve learned that I feel better and am much more effective when I simply “drive” a thought instead. When I see a thought as a means of trying to make sense of things, rather than as part of who I am, I don’t get sucked in. I relate to the thought, but the thought doesn’t bind me.

I call this going BMW: going Behind the Mind and Watching. During, after, or even while anticipating an episode with your teen, try the following to get behind your thinking and become your own witness.

- Recognize to yourself, I’m having the thought that [insert rigid thought]. This will help you step back and watch the thought. This is very different than arguing with a thought or trying to force a thought away.

- Think to yourself, Thanks, mind, for coming up with [insert thought].

- Take a breath and mentally place the thought in the corner of the room. Visualize the shape, color, size, movement, and sounds that describe the thought. For a few breaths, just watch it there in the corner.

- Ever see Charlie Brown cartoons? Remember how the teacher sounded to the kids? Wah, wah wah wah wah! Take the highly charged thought your mind is zapping you with and imagine that, instead of “you” saying it, it’s that cartoon teacher saying it instead. Give the thought the same amount of attention the Peanuts kids did to their poor teacher.

- Think the thought very slowly, as if it’s a recording on a scratched CD.

- Regard the thought as if it’s a car passing you, as you, the witness, merely drive alongside.

The goal with all of these techniques is to shift from a rigid, absolute frame of thinking to foster instead a more flexible relationship with your mental experience. This requires a lot of practice. To be of real benefit, this practice must become a habit. Such a habit will give you a measure of psychological freedom amidst even the most challenging provocations.

Learning to See Behind Behavior

The next set of practices builds off your mindful presence of your sense experiences, as well as the understanding you’ve acquired of your thoughts and emotional patterns. Once you can accomplish this, you open up the possibility of seeing behind your teen’s behavior in a compassionate way. This is the heart of the PURE method. You’re taking it all in. You’re not reacting—or, at least, you’re not reacting as much as you have in the past. You’re able to bring in and authentically hold what’s driving things for your teen. You’re getting past the hard aspects of correspondence bias and seeing what deserves some empathy.

Here’s a cardinal rule of anger: all angry behavior is driven by authentic need. It serves a function and a purpose. It may not be appropriate to the situation, it may be maladaptive, self-destructive, and downright dangerous, but it’s authentic all the same. With consistent practice of presence and understanding skills, you will begin to see this rule as true for your teen. And there’s a bonus: you will also begin to see the rule as true for yourself. That’s a really worthwhile silver lining.

Let’s begin to build this deeper seeing with a skill that brings us back to the basics of breath.

Skill Practice: Gap Breathing

When there’s a moment of tension with your teen and it feels like the world’s at stake, don’t just prepare another point you want to make about your teen’s behavior. Instead, use this breathing skill to connect you to what is most real for your teen behind the content of whatever you two are at odds about. Or, during a moment with your teen that is not immensely challenging but instead rather mundane, try the following:

- Turn your attention away from what your teen is saying and doing. Instead, focus on your teen’s breathing. See if you can notice the rise and fall of moment-to-moment breath. Start to track the rhythm of your teen’s breath. The goal is to tune in to what’s happening physically in that moment.

- Listen through the gaps between your teen’s words. Notice the small pauses and breaks in speech. The hesitations, the stops and starts, the ums and uhs.

- Listen to the spaces. Can you hear the moments of meaning in your teen’s tiny silences?

- Notice what happens to your own awareness, thoughts, and responses after paying such close attention. How might your next action be more or less effective than if you’d simply waited and then jumped in with a more typical reaction? You don’t need to do or say anything to your teen about this, and you need only do it for a few moments.

- Note in your journal anything you have gleaned about what’s most important from your teen’s perspective. Return to the RSVP themes from chapter 1: respect, space, validation of feelings, and peers and provisions. Do your teen’s bodily reactions suggest one of these things is at stake (at least from the teen’s perspective)? Do they suggest your teen feels hurt, rejected, maligned, ignored, or like a failure in some way? Are you willing to get curious about the clues gestures and nonverbals can offer?

In the next practice, you’ll deepen your understanding of what matters most to your teen—what’s driving and fueling the anger. For this you’ll need a blank piece of paper and an envelope.

Skill Practice: Sending and Receiving the Real Letter

- Close your eyes and call your child to mind. Don’t just think about your teen though—see your teen vividly in your mind’s eye. How does your teen typically look? How does your teen sit, walk, and talk? What does your teen sound like? No judgments here, just visualize and notice. Once you have your teen vividly in mind, allow a recent difficult interaction to come to awareness, a time when communication broke down and anger flared. You might imagine it as a movie clip played in slow motion. Again, don’t judge, just notice. Don’t try to force the memory to surface. Let it come to mind in its own time.

- Sit in a quiet place where you won’t be disturbed for at least ten to fifteen minutes. On the envelope, write the specific external actions—the things you did or said—of this interaction. If you were angry that your teen didn’t uphold an agreement, write out how you “used a sharp tone,” or how you “lectured on how this has happened before,” or that you “looked away and abruptly changed the topic.” Whatever your actions were, list them. List them all, even if they include reactions you’re now a bit ashamed of, such as swearing, yelling, accusing, or threatening. Write across the front and back of the envelope.

- Next, taking the blank piece of paper, think about what deeper message you wanted your teen to receive. What was the intent behind the actions on the envelope? What was the feeling or need driving what you said? It might have a lot to do with worry or fear. Perhaps you were deeply concerned for your teen’s safety and future happiness and were trying to ensure your teen finally got on the right track. You’ll likely find that these deeper messages relate to values of yours that have become blocked or stuck in some way. Whatever the deeper message, write out your best sense of these behind-your-behavior intentions and feelings.

- Fold the letter, slip it into the envelope, and put it down.

- Clear your mind. Center yourself with a minute of focusing on your breath. When you are ready, hold the envelope in your hands. Imagine that you are not you anymore—you are your teen. You have just received this letter in the mail. Read what’s written across the envelope, all the actions and words hurled at “you.” Read the words slowly and deliberately. To deepen the processing, you can even say them aloud if you like.

- Sit for a moment with your eyes closed, feeling whatever arises as you imagine yourself as your teenager receiving this letter in the mail. What would be your impulse? What would you want to do with this envelope? Notice any thoughts or reactions that arise. It’s a safe bet you’re noticing little interest in what might be inside the envelope. You might even want to just toss the whole thing.

Has your teen been disregarding your letters—the true messages—because of the emotional and behavioral scrawls all over the envelope?

Skill Practice: Function Junction

In the previous practice, you likely got a visceral sense of why your teen misses your intended, valid messages. Now, let’s take this a step further and help you connect with the true function of your teen’s behavior. This practice helps you read the real letter inside even when the envelope makes you want to stamp it return to sender.

- With a fresh envelope, do the same activity as above, but from your teen’s perspective. What are your teen’s observable behaviors—what does your teen do—when angry? Write these on the front and back of the envelope.

- Next, on a fresh piece of paper, write your most compassionate, nonjudgmental guesses—think RSVP, think coercive cycles—about your teen’s true message. What are your teen’s unmet, blocked, or threatened needs? What values feel endangered to your teen?

- If it feels appropriate, you can ask your teen to complete an envelope and letter. (If a family clinician is already involved, clinical assistance can be very helpful here.) Sometimes teens will be willing to write down not only the many angry things they do, but the authentic needs behind these behaviors as well.

- If your teen does complete an envelope and letter, consider sharing your letters with each other. Such sharing can have a significant positive effect. However, only do so if you have put in the time and effort to practice the skills we’ve covered so far. You’ll want to be able to slow down your body, recognize emotional patterning and rigid thinking, and mindfully maintain perspective. If you’re not there yet, hold the letters until a later time. You will be ready soon.

The communication strategies in this book will help you connect with—though not necessarily agree with—your teen’s perspective and needs. With their foundations in mindfulness and positive psychology, these strategies also help you to recognize the emotional and communication factors driving interactions and to respond skillfully and compassionately. As you practice, you will increasingly be able to help your teen—and yourself—move past the nastiness on the envelopes to the heartfelt letters inside.

The Courage of Compassionate Communication

Actor John Wayne got courage all wrong. His cinematic version of bravery portrayed it as a manly quality tied to an absence of fear and distress. As most of us know all too well, the toughest episodes overflow with fear and distress. True courage is doing what matters to release stuck patterns, despite the fear and distress and despite the pull of patterning.

To wrap up this chapter, let’s explore a practice that can be used in any difficult moment. It’s a simple process, but if practiced consistently, can have a profound effect.

Skill Practice: Hijacking the High Road

This practice can be used daily and is a way to begin practicing multiple skills that we’ve covered thus far in the book. When feeling stuck with your teen, do the following:

- Establish yourself in presence with any of the mindfulness practices from chapter 2. Do so for at least several seconds.

- Drawing on the Relational Compass, quickly notice any pull toward patterns of reactive closing that you may be experiencing.

- Maintain presence. Imagine yourself resting in awareness at the very center of the Relational Compass.

- Use mindfulness of thought—your BMW skills—to distance yourself from biased or distorted thinking.

- Establish your understanding of what matters most in this moment. What needs or values are most pressing? What is behind your behavior? Your teen’s behavior?

- Ask yourself: Am I willing to let go of my pattern and teach my teen the most valuable lesson I can right now? Or, more simply: Right now—will I open or close?

If you can hijack moments of difficulty in this way, even just occasionally, you will be on your way to ending communication breakdowns.

Peaceful Parent Practice: Hang Time with Your Teen

Parents who intentionally set aside time to connect with their children—including teens—and who work to modulate their emotional reactions are more likely to experience both improvements in the relationship and decreases in children’s acting-out behavior (Kaminski, Valle, and Filene 2008; Obsuth et al. 2006). The following recommendations derive from a family intervention called Children Adult Relationship Enhancement, developed within a highly researched approach called Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (Chaffin et al. 2004). It’s a set of guidelines for what to do and what to avoid during regular hang time with your teen.

When the relationship between a parent and teen is strained, the last thing a parent may feel inclined to do is spend precious free time hanging out with angry offspring. But that’s exactly what this practice is asking of you. It is one of the most important practices in this book for shifting your relationship from conflict to connection.

- Schedule at least ten (ideally fifteen or twenty) minutes daily to hang out with your teen, regardless of how difficult interactions have been. This is particularly hard to do when a day has included intensely upsetting exchanges. Do it anyway. Hang time is not a reward to be earned; it is relationship medicine dosed daily regardless of when things are challenging.

- Let your teen choose an activity. Ideally, it’s something interactive, like a card or board game, but it may have to be an activity the teen is doing with you involved only as an observer, such as checking social media or playing an online game. It’s crucial that you not dictate the activity.

- Here’s what you want to do:

- Praise your teen’s effort and any behaviors during the interaction you can. Stretch if you have to, but avoid contriving compliments. For example, you might say, “I like how you gave that a lot of thought,” or, “I appreciate how real you can be with people,” or, “Thanks for giving me a chance to try this.”

- Paraphrase what your teen says, particularly the things that seem important to your teen. For example, “It sounds like you feel like that friend has it in for you.”

- Point out what your teen is doing during the interaction so it’s clear you are really paying attention. Point out, too, the things your teen is doing and saying that help the interaction flow smoothly. For example, “You’re pausing to give me a chance to give my take on things,” or, “Looks like you’re switching to a different character in the game.”

- Here’s what you want to avoid:

- Do not ask a lot of questions. If possible, do not ask any. Teens often perceive questions as being driven by an agenda—especially teens expecting conflict with parents. Leave questions alone no matter how tempted you are to pry or probe.

- Do not lead things or try to lecture. Hang time is not the time to teach anything. Swallow that impulse. Do not redirect your teen’s behavior unless it becomes highly disruptive or disrespectful. If this occurs, calmly tell your teen that you need to end the hang time for now—and that you’re looking forward to next time.

Think of hang time as an investment. You’re making a deposit during a down economy, on professional recommendation—mine and the literature’s—that doing so will yield exponential dividends in the future. Keep showing up and giving your teen this specific, attuned attention. Even if your teen scoffs or shrugs you off, your perseverance will pay off.

Peaceful Parent Practice: The Theater of the Mind

This chapter’s additional Peaceful Parent Practice is a contemplation to return to regularly. The practice helps you achieve an emotional and mental altitude where perspective and understanding are more possible. While it’s not an in-the-moment PURE practice, it can still do much to purify your intentions as a parent.

We go to the theater to see scripted interactions between characters. In our real, personal lives, we can do better. We don’t have to follow our old scripts for our family patterns. We can improvise if we choose. Ask yourself: Am I willing to create a new relationship with my experience of my child right now? Your answer will determine whether the old pattern continues or if you take a new step forward. We can write new scripts for how we want to handle the emotions cropping up. As we do, others—especially our children—will notice us doing so. Even our small actions can have significant positive ripple effects.

Consider journaling for a few minutes. What old pattern—perhaps a coercive cycle—has recently surfaced in your parenting? As you write, note the thoughts, feelings, and even actions that rise up. Is it easy or difficult to stay with whatever your mind shares? If it’s difficult, are you willing to stay with it anyway?

Consider again for a moment: Where did you learn your unworkable patterns? Where did your kids learn theirs? What about others in your life? What happens to your part of the pattern when you rest in skills of presence from chapter 2? When you rest in the skills of understanding from the current chapter? What will happen to the emotional inheritance you pass to your teen if you respond to your pattern in these ways?

Your Parental Agenda

As you move on to the next chapter:

Continue your daily formal meditation practice.

Continue your daily in-the-moment presence practices.

Consult appendix A (available for download at http://www.newharbinger.com/35760) for more guidance on how to tailor practices of compassionate understanding to fit your needs.

Begin and maintain daily hang time practice with your teen.

Make going BMW with your thinking a daily habit. Build a wide angle lens to see the process of your thinking, particularly in the moments before, during, and after tough interactions.

Use your journal for reflections and insights regarding this chapter’s discussion of the Relational Compass, your own patterns of emotional reaction, and your experiences in working to create more emotional attunement with your teen.

Figure 3.1: The Relational Compass

Figure 3.1: The Relational Compass