Ce que nous voyons dans l’Afrique n’est ni merveilleux ni rare; … la ‘Politique’ d’Aristote ne convient pas moins à ses bourgs de moëllon et de boue qu’aux cités éclatantes du monde grec.

Emile Masqueray, Formation des Cités

chez les Populations Sédentaires de l’Algérie1

Of all the odd forms of government, the oddest really is government by a public meeting.

Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution2

The jema‘a in the sense of occasional assembly or council is found in all Berber societies, including that of the Rifians. It is not peculiar to the Berbers, however. The Arabic-speaking tribes of Algeria and Morocco (at least) certainly had – and in many cases still have – their jemāya‘. In Kabylia, jemāya‘ of a kind are found at every level: an ad hoc ‘council’ of the adult males of a single family or lineage will be called a jema‘a, although a wholly makeshift affair. But these improvised and occasional jemāya‘, so characteristic of Maghribi tribesmen in general, are not characteristic of the Kabyles. They are incidental rather than fundamental to their political organisation.

There are two kinds of jema‘a which are characteristic of Kabyle society and fundamental to its political organisation, one of them a special body, the other a special place. Both of them are institutions. (The same word, jema‘a or, in Berber, thajma‘th, is used in the two cases; there are different kinds of jema‘a, but no constant difference of meaning between the variant forms of the word.)

Figure 4.1: Thajma‘th at Taourirt Mimoun, Ath Yenni.

The first kind of jema‘a characteristic of Kabylia is the one I have already been discussing, the deliberative assembly which is both the sovereign legislature and law court of the village. The literature on Kabylia suggests that this does not function in a wholly uniform manner throughout the region, but the principal authors, in presenting descriptions which differ from one another, have apparently been unconscious of this diversity and each has conveyed the impression that his or her account of the matter is generally valid.

If it were the case that in all the many hundreds of villages in Greater and Lesser Kabylia the jemāya‘ functioned in an identical manner in all essential respects, this would strongly suggest that the political organisation of Kabyle villages was the product of a general sociological law rather than the historically evolved artifice of sovereign communities. In fact, however, there is a discernible variety in the functioning of the jema‘a from one village to another. Beyond minor matters of detail, this variety concerns the way in which the Kabyles handled the distinction universally observed between ordinary adult males in general and those few senior figures possessing especial influence – the ‘sages’, l-‘uqqāl.3

There are, or were, three main variants. In some cases, the full assembly of adult males is a frequent and regular event, taking place every week or every fortnight and dealing with all matters which may arise, but its deliberations are dominated by the ‘uqqāl, the others speaking only (i) very occasionally and at many meetings not at all, (ii) when especially concerned by an item under discussion and (iii) after such ‘uqqāl as wish to speak have had their say. In this case, there are some grounds for saying that, within the form of an egalitarian and democratic assembly, the substance of government is an oligarchy of the wise. This is the variant described by Mohand Khellil4 and his account may well be valid for much of Kabylia outside the Jurjura.

In other cases, the body which meets regularly is quite explicitly the assembly or council of the sages, thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl, who sit together in the limited space of the village thajma‘th (which in this case is a small rectangular building with a roof and stone seats along the inside walls, very like a much enlarged porch or covered gateway, and usually open at either end) and discuss the business of the village, while the rest of the men of the village stand or sit around the thajma‘th and listen to the discussion without taking part in it. This procedure, which is that described by Masqueray,5 is oligarchic in form as well as substance, but not more oligarchic than a representative assembly in a modern state, in that the lineages and clans are represented among the ‘uqqāl, each by a spokesman, tamen (plural: temman). This form may well be the tradition of some Jurjura villages, as Masqueray suggests, but it is not that of all of them. For there is a third variant, which is also evoked by Masqueray6 and alluded to by Basagana and Sayad in their monograph on the village of Ath Larba‘a of the Ath Yenni,7 which should be distinguished from the two already mentioned. In this case, there are two distinct bodies, the council of the sages (thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl) on the one hand, which consists of the officers of the jema‘a – amīn (president), wakīl (secretary/treasurer), aberrah (public crier) and the temman – and a few ‘elder statesmen’ of the village in addition to these and meets regularly and frequently and, on the other hand, the full assembly of all adult males, which meets on particular occasions in the annual calendar and also whenever convoked for a particular reason by the thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl. It happens to be the variant which has obtained at Ath Waaban and a description of the procedure followed there may serve to convey the spirit and flavour of the thing.

At Ath Waaban, the thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl meets every week, on a mid-week evening, when the men have come in from work. It considers the current affairs of the village, receives reports and hears complaints and then proceeds to take the necessary decisions. Since Ath Waaban does not possess a building for its jema‘a, unlike many other villages, the thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl meets in the ‘old schoolhouse’, which dates from the late colonial period and is no longer used as a school (the village now possesses newer schools). The meetings are not attended by the rest of the men of the village; the only non-members of the thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl who attend are those who have significant news or complaints to lay before it; these are free to attend the entire meeting or to appear only for their own item on the agenda, as they prefer. The prerogatives of this council are quite limited.8 For all important or controversial matters, such as the promulgation of a new article of the qānūn or the building of a new public facility (road, bridge, mosque, schoolhouse, telephone box, etc.) or a question of the village’s external political relations, it will summon a meeting of all the men of the village. This plenary session of the village jema‘a is known as aberrah, which may be translated as ‘convocation’ or ‘summoning’. Thus the men of honour of Ath Waaban resemble the dons of Oxford University in at least this respect, having both a hebdomadal council and a convocation.

Figure 4.2: Thajma‘th Oufella at Jema‘a n’Saharij in use during an arts festival, July 2012.

Figure 4.3: Ath Waaban today, seen from the east end of its high valley in the Jurjura. The village was the HQ of the ALN’s Wilāya III from May to December 1957, when it was destroyed by the French. It was rebuilt after independence.

At Ath Waaban (and doubtless elsewhere), the aberrah is held on a Friday, the Muslim day of rest and prayer, in the open air on the site designated as the place of assembly and in the morning, starting promptly at 8 o’clock. The village crier (also known as aberrah, i.e. ‘the man who summons’) announces the aberrah from a convenient place in the village centre at sunset the previous evening, at first light the following morning and again at 7.30 a.m. The roll call is taken at about 7.55 a.m. and anyone who is late is fined. A second roll call is taken after the meeting has been in progress for half an hour and anyone who is still unjustifiably absent is subject to a second, much stiffer, fine. (In 1983, the rates for these two fines at Ath Waaban were ten and fifty dinars respectively – about £1.50 and £7.50 at the official rate of exchange.)

The aberrah is not dominated by the ‘uqqāl. It is certainly the case that men who have acquired particular influence and personal authority are called to speak first, and that the assembly shows them the respect due to their experience and proven judgment. But this is an unwritten rule which is entirely of a kind with the unwritten rules which tacitly regulate the functioning of many a democratic assembly in modern states. In the aberrah at Ath Waaban, every man has the right to speak and this right is widely and frequently exercised as a matter of course.

The villagers of Ath Waaban do not consider this extremely democratic system to be a recent innovation. They affirm that this is how they have always conducted their affairs. And, since their village is one of the remotest in the Jurjura and in many respects one of the most traditional in the region as a whole, I know of no reason to doubt them on this point. They appear, moreover, to take it for granted that their practice is shared by their neighbours in the central Jurjura, as it very probably is. The physical proximity of and social intercourse between neighbouring villages in Kabylia are such that, were Ath Waaban’s political procedures significantly different from those of their neighbours, the people of Ath Waaban would certainly be aware of the fact and self-conscious about it. This is not the case. Indeed, my principal informants there were surprised and intrigued when I pointed out to them that the political arrangements of villages in certain other districts of Kabylia differed from their own.

These political arrangements have survived at Ath Waaban to this day.9 If there has been any change in recent times, it is that less importance than previously is attached to the sheer fact of age. In the old days, young men attending the aberrah would rarely, if ever, speak in the presence of their father or another older male of their family. This traditional inhibition, which, like the deference shown to the ‘uqqāl, is a particular instance of the general respect shown to one’s elders,10 is still in force, but the deference in question is displayed with less punctiliousness than previously; the inhibition is undoubtedly weaker than it used to be, although probably still stronger at Ath Waaban than in many of the less remote, more ‘evolved’, villages to its north.

These are the three main variants of political organisation at village level in Greater Kabylia.11 In all cases, it cannot be seriously disputed that the village jema‘a (whether a single body or one differentiated into a limited council plus plenary assembly, the former functioning as the executive of the latter) possesses the basic attributes of a political institution. Its meetings are conducted in accordance with a clear procedure known to all and are convened at regular and frequent intervals, it has its own officers and procedures for determining them, and it has its own site and usually its own building. Above all, as we have seen in our consideration of the qawānīn, it has authority to make and enforce law, which in the old days extended to the power of life and death in certain cases, and it unquestionably has a corporate existence independent of the social groups represented within it, illustrated by its right to compel attendance and punish unwarranted absence, among its other, comparable, powers and prerogatives.

So much for the first kind of jema‘a. The second kind of jema‘a is not an assembly in the sense of a political institution, but a place of assembly, a forum for public life in general rather than the venue of particular political or judicial proceedings. While the jema‘a or thajma‘th in the first sense is the council of the village as a whole, the jema‘a or thajma‘th in the sense of public place is found in each of the principal quarters, ikhelijen, of which the thaddarth is composed. Thus, at Ath Waaban, both the thakhelijth of the Ath Tighilt and that of the Ath Wadda have their own thijemmu‘a, one apiece. But, although a thajma‘th in this sense will invariably be associated (and sometimes, but not always, identified by name) with a particular quarter and so, by extension, with a particular clan or group of clans or lineages, it will not belong to this quarter alone, but to the thaddarth as a whole: any man, from any quarter or clan, has the right to sit in any thajma‘th and will be made welcome there, with great courtesy, whatever his kinship or political relationship with his ‘hosts’ and whatever their private feelings towards him.12 For each of the thijemmu‘a of a given thaddarth forms part of the common property of the thaddarth, the land in question – like that on which the mosque, schoolhouse, etc. stand – belongs to the thaddarth as a whole and, while the men of a given quarter enjoy de facto possession of ‘their’ thajma‘th and feel at home there, this possession falls short of proprietorship since it confers no right to exclude the men of the other quarters.

Most of the thijemmu‘a of this kind in Kabylia do not perform political functions directly. At Ath Waaban, for example, the aberrah is held in neither thajma‘th n’Ath Tighilt nor thajma‘th n’Ath Wadda, but in a third spot on the borderline between the two quarters in the heart of the village. This place, the only one used for meetings of the village’s plenary assembly,13 is used for nothing else. Its only virtue is that it is neutral ground, so to speak. It is not a place where men gather informally to pass the time of day, whereas the thijemmu‘a of the two quarters are precisely that. Nonetheless, while not the site of collective decision-making, the latter have a fundamental importance in the political life of the village.

The jema‘a of the quarter is the place where men meet, exchange news and discuss current affairs informally. While courtesy is de rigueur, rivalries and enmities are discreetly expressed and monitored by onlookers, since conversations can be overheard and comportments witnessed by all. The fact that two men exchange no more than the minimum greeting politeness demands before warmly saluting others and engaging them in animated conversations, for example, conveys to others present the state of relations between two families or lineages. The jema‘a is the stage on which public announcements can be made, by implication and gesture and nothing more, as often as not. (The Ath A and the Ath B are reconciled; relations between the Ath C and the Ath D are as bad as ever, and so on.) It is also the place where news from the village’s immediate environment is registered; the news itself is gathered at the market and reported by villagers on their return, who invariably make the jema‘a their first stop if they have interesting information to transmit. In various ways, then, the jema‘a is the forum within which public opinion informs itself and ripens. It is correspondingly essential for every Kabyle man to spend some time there every day and a man who fails to do so will soon be the object of adverse comment. Why does So-and-So no longer come to the jema‘a? Is he unwell? If not, what is wrong? Do the affairs of the village no longer concern him? Does he no longer feel the need to know the opinions of his fellow villagers? Who does he think he is? (I have witnessed conversations of this kind at Ath Waaban.)

The point is that, in Kabylia, the very idea of being a man is bound up with the idea of being a citizen – that is, a member of a political community. The jema‘a of the quarter is the civic forum and, while in most villages there will always be one or two individuals who, for some reason or other (to do with dramatic incidents in the past as often as not) emphatically stay aloof from routine village affairs, men with no such generally understood motive will not be allowed to shirk their civic role and public pressure on them to assume their responsibilities will eventually take the form of a questioning of their manhood. To stay at home is what the women do. A man must show himself, must play his part in public life, must keep the company of his peers, take the risk of confronting them and expose himself to the claims and challenges of other men.14

The place where public opinion forms, where the man acts the citizen, the jema‘a is also and consequently the arena in which boys and young men are socialised into the public life of the village and undergo a major part of their apprenticeship of manhood, by listening to the conversations and arguments and observing the public comportments of their elders.15 It is also the collective memory of the village and its window on the world. During the summer, the young men will stay at the jema‘a long into the night, listening to recollections of past events, arguing the pro and contra of long decided disputes. (In 1975 and 1976, I heard the most remarkable conversations about the political and military history of the Revolution in the jema‘a of the Ath Wadda at Ath Waaban.) And every traveller returning from foreign parts – France, Morocco, Tunisia, or the other regions of Algeria – will be expected to recount his experiences at the jema‘a and will look forward to doing so. (These days, the news may be of Canada and England, the United States, Germany and Sweden, or even Australia.) In this way, the minds of young Kabyle men are trained in public affairs and simultaneously oriented to and informed about the outside world from an early age and their curiosity about other countries and societies stimulated.

The jema‘a of the quarter has been performing this complex role and having these remarkable effects in virtually all the villages of Kabylia and, above all, the villages of the central Jurjura for generations.

Among the Berbers of the Rif or the Central High Atlas, the jema‘a in this sense does not exist, or is only very rarely found.16 Apart from mosques, law courts, mahākim, dependent on the central power, and markets, there is no public place, merely private territories on the one hand and the no-man’s-land of the occasional township or military outpost and the roads which lead to them on the other. But the thijemmu‘a of a Kabyle thaddarth are not no-man’s-land. They each have their own horma (honour) and ‘anāya (the consideration they are owed and the protection they consequently afford).17 No-man’s-land has neither horma nor ‘anāya. It is the realm of shamelessness and sauve-qui-peut precisely because it belongs to no man. But, as Mouloud Feraoun has put it so well, ‘la djemaa est à tout le monde en général et à chacun en particulier’.18

The complex character of the thajma‘th, the public space par excellence, as public property which is in the virtual private possession of a particular quarter, a private possession which is qualified and controlled by the ability of men from other quarters to exercise their right to make use of the space in question as public space in the certainty that this right will be admitted, directly reflected the third way in which the Kabyles coped politically with the contradiction between the code of law and the code of honour, which was also the way in which a Kabyle thaddarth afforded alternative modes of expression to the feuding impulses of its constituent families. This was by building into the political system which underlay and informed the functioning of the village council a major element of representation of kinship groups, but on terms which, while satisfying the latter, underwrote and consolidated the supremacy over them of the former. This was done in two ways, through the agency of the temman and through the medium of the sfūf.

The position of the tamen has not been adequately explained in the literature on Kabylia. On this, as on so many other questions, an examination of this literature reveals a striking, if hitherto unremarked, diversity of interpretation.

Favret refers to the temman as ‘the leaders of lineages’.19 It is possible that the thajma‘th in some of the remoter parts of Kabylia is, in effect, a mere assembly of lineage heads, which is what it appears to be in the Central High Atlas of Morocco. But this is not the position in the heartland of Greater Kabylia, and least of all among the Igawawen. Here the tamen is by no means necessarily the leader of his lineage; the informal functions of lineage leadership and the formal functions of the tamen are distinct, and neither set of functions implies or presupposes the other.

Khellil refers to the tamen as a ‘representative’ or ‘delegate’ or ‘proxy’ (mandataire), presumably employing these terms as synonyms. He does so in the course of presenting a picture of the thajma‘th which resembles that required by the segmentarity theory, in which power emanates from below and the thajma‘th itself is essentially an assembly of heads of segments without institutional authority of its own:

Each entity within the village delegates its representative in the tajmaat, the village assembly. Axxam will send to the assembly the head of the household (bab bbwexxam); for adrum, it will be ṭṭamen, so that finally the village designates its chief, lamin, among the latter …20

Elsewhere, however, he speaks of the temman as ‘the assistants’ of the amīn and notes that the amīn may delegate his powers to one of them on occasion. But this is presented by him as only a slight qualification of the temman’s primary role as defenders of ‘the particular interests of their respective fractions within the assembly’, which, he reminds us, ‘is a meeting of families’.21

It is quite possible that this interpretation is valid for the Ath Fliq, the ‘arsh to which Khellil belongs and on which he has based his analysis of Kabyle society in general. If so, it probably also holds good for the neighbours of the Ath Fliq – that is to say, the ‘aarsh of maritime Kabylia to the north of Azazga. But it is not valid for the ‘aarsh of the central Jurjura and thus, if accurate, actually confirms the distinction which I have already drawn on other counts between the Igawawen and the rest of Kabyle society.

Tamen does not mean representative or delegate or proxy or lineage head or even assistant of the amīn (although the temman are, in practice, the assistants of the amīn). The word is the Kabyle form of the Arabic dhamīn, meaning ‘responsible, answerable or liable for; bondsman, guarantor, surety’. The tamen does not represent his lineage22 so much as answer for it. He gives undertakings on its behalf, he vouches for it. This was understood by Masqueray and by Hanoteau and Letourneux, who translated it by the French words caution and répondant, which have precisely the principal meanings of dhamīn.23

The tamen answers for his lineage in two main contexts, in the regular meetings of the jema‘a or thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl and on the intermittent occasions of the sharing of meat for public feasts (thimshret), when it is the tamen who receives on his lineage’s behalf the meat which falls to its share. In the jema‘a, the tamen answers for his lineage in numerous different ways: when a decision has been taken, he answers for his lineage’s willingness to respect this decision and accept it; if the decision involves some demand upon the various lineages – a mobilisation of labour, the provision of fighting men, the raising of money to finance a communal project and so on, he is the guarantor of his lineage’s willingness to furnish its quota. Above all, he answers to the jema‘a and so, through the jema‘a, to the village as a whole for the behaviour of the people of his lineage; it is the tamen who pays the fines imposed on individual members of his lineage for whatever transgressions they may have committed.

In some villages, the temman will also be the prosecutors of individual misbehaviour, in that complaints will be made to them in the first instance, which they will then transmit to the jema‘a or the thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl for judgment. But it is in their capacity as members of the thajma‘th l-‘uqqāl and thus as officers of the jema‘a as a whole, rather than that of ‘answerers’ for their respective lineages, that they perform this prosecuting role. That there may be a very real element of ambiguity in this is evident: in bringing a charge against a member of another lineage, is a given tamen acting on behalf of the village as a whole by upholding the village law, or is he acting on his own lineage’s behalf and scoring off a rival lineage?

It is probable that the political danger inherent in this ambiguity will have remained latent, as a possibility only rarely realised in practice, in most Kabyle villages. In the tuwāfeq, the physical separateness of the constituent lineages, each residing in its own hamlet, would limit the occasions for complaints arising between them. In the smaller thiddar, the presence of a public opinion that is permanently well informed about all the goings-on would be likely to deter any tamen from bringing other than well-founded charges against members of hostile lineages. The problem, then, is most likely to have arisen in the unusually large thiddar of the Igawawen, where the sheer size of the village and its population would be likely to reduce appreciably the effect of public opinion in this particular context, since, having to remain abreast of events in a larger community, it would be less likely to be completely au fait of the details of every little incident. If this reasoning is sound, it would explain the fact that it is in the Jurjura that a most interesting variation on the position of the tamen is to be found.

At Ath Waaban, which, I have argued, is likely to be broadly representative of its Igawawen neighbours in these matters, there are two, quite distinct, kinds of tamen: the man who answers for his lineage in the jema‘a, known as tamen bu afrag,24 and the man who reports infractions of the qānūn to the jema‘a and proposes the appropriate penalty. The latter is known as tamen n’lakhda, ‘the tamen of fining’.25 Whereas each lineage has its tamen bu afrag, such that there are 23 temman bu afrag in all at Ath Waaban,26 there are only four or five temman n’lakhda, and they are not chosen on grounds of kinship representation at all. For example, the lineages at Ath Waaban are broadly grouped in four iderman, but the temman n’lakhda are not chosen on this basis, one per adrum. They are designated by an aberrah of the full assembly of adult males on the basis of their personal qualities, irrespective of their lineage and clan backgrounds. The qualities sought are integrity and decisiveness.

Figure 4.4: A classic thajma‘th at the Igawawen village of Thirwal, Ath Bou Akkach.

Figure 4.5: A thajma‘th at Guenzet n’Ath Abbas in Lesser Kabylia.

In other words, the Igawawen village had policemen. This is clearly inconsistent with Gellner’s claim – a generalisation from the case of the Central High Atlas in Morocco – that Berber society everywhere lacked specialist agents or institutions of order-maintenance. It also puts further in question some of the premises of Durkheim’s social theory,27 for the existence of policemen in the Igawawen villages has clearly been the fruit of the development of the social division of labour among them, necessity being the mother of invention.

But, in all villages, the temman, whether combining these two functions or distinguished by their responsibility for only one or the other, exemplify the primacy of the village collectivity as a whole, articulated by the jema‘a, over the lineages and clans of which the whole is composed. To say that the tamen bu afrag or tamen bu akherrub ‘represents’ his lineage is thus misleading. The entire spirit of his title and function is that he represents the jema‘a to his lineage and answers for his lineage to the jema‘a. This is more or less the opposite of the role of a representative politician in a modern liberal democracy.

In this way did the jema‘a of a Kabyle village assert its primacy over the centrifugal forces of kinship solidarities and antagonisms, while taking care to knit the kinship groupings into its own functioning via the agency of the temman. But it was not the only way in which this was done. The second way was through the action of the sfūf.

Saff (generally pronounced seff in Kabylia) is an Arabic word (plural: sfūf) meaning ‘row, array, alignment’. It is conventionally regarded by anthropologists as the Algerian counterpart of the Moroccan term liff or leff (plural: ilfūf), which is also derived from an Arabic word, laff, with the rather different primary meanings of ‘circumambience, circumvention, subterfuge’.28 Liff is usually translated as ‘alliance’, but alliance can, of course, mean many different things, from an informal agreement between two politicians to a formal electoral pact between two or more political parties (e.g. the Alliance of the Liberal and Social Democratic Parties in Great Britain 1982–7) or a highly institutionalised system of collective military security composed of sovereign states (e.g. NATO, ‘the Western Alliance’).

The liff systems in south-western Morocco as described by Robert Montagne were collective security systems of a kind, in which tribes adhered to one or the other of two regional alliances. The tribes of the Nfis valley in the Western High Atlas belonged to the liff of the Aït Iraten or that of the Aït Atman; their neighbours to the west belonged to the liff of the Indghertit or that of the Imsifern, while those of the Anti-Atlas belonged to the liff of the Igezulen or the liff of the Isouktan.29 These alliances may have maintained a kind of order or security at the regional level but in Gellner’s view they cannot be credited with having maintained order at other levels because they were not implicated in the way in which the constituent tribes and sub-tribal communities were governed.30

In the Rif, a very different system of liff alliances has obtained. Hart has argued that there were two types, the permanent (or relatively permanent) ilfūf at the upper levels of the social structure and the lower-level temporary ilfūf.31 These alliances or, rather, in this context, factions existed within each tribe, their components being clans or, in some cases, sub-clans, but the factional alignments would sometimes cut across kinship links and a given liff in tribe A would often include a neighbouring clan or sub-clan of tribe B. It is clear from Hart’s account that the system of liff alliances took precedence over segmentary kinship links in what one may call political life in the Rifian tribes,32 but also that the activity of the ilfūf was secondary to the blood-feud and that factional conflict did not tend to sublimate and contain feuding impulses but to correspond to and reinforce them.33

Whatever may be the truth of the matter amongst the Rifians or the Chleuh, the saff systems of the Kabyles cannot be grasped by means of putative analogies with Moroccan ilfūf. It is possible that elsewhere in Algeria, amongst the Chaouia of the Aurès, for instance, or the pastoralist tribes of the High Plateaux and the Sahara, the sfūf approximated to the ilfūf of the Chleuh or the Rifians. But, in Greater Kabylia, the sfūf were not alliances in the sense of collective security blocs nor factions that corresponded to opposed feuding groups. Nor were they, as Bourdieu has claimed, moieties which maintained order through the equilibrium they created in opposition to each other in a kind of ‘dualist organisation’ which ‘guarantees a balance of forces through strange processes of weighing, a stalemate resulting from the crisis itself’.34 As Favret, reiterating Hanoteau and Letourneux, has pointed out, the sfūf were not of equal but of manifestly unequal strength.35 Order was not, therefore, achieved through some ‘strange process of weighing’ because there was no such process. Nor, we may add, was there any stalemate.

Unfortunately, Favret does not follow up her pertinent observation about the inequality of the sfūf into a coherent explanation of their nature and functioning. Although she frequently cites the nineteenth-century observers against their twentieth-century successors, by rendering ‘sfūf’ as ‘leagues’ she departs from the most important insight of the former’s accounts. For, as Hanoteau and Letourneux realised, the sfūf of Greater Kabylia were parties.36

The basis of the Kabyle saff systems as systems of party division and competition was the combination of four facts: first, the fact that the system of self-government of the Kabyle village rested on the authority of the jema‘a and thus upon the primacy of the legislature; second, the fact that every Kabyle village was part of an ‘arsh comprising a number of villages and possessing its own jema‘a in which all the constituent villages were ‘answered for’; third, the fact that, notwithstanding the formal equality of status of all Kabyle men, the accidents of birth and fortune and enterprise entailed that, within any one village, certain families would be larger, more prosperous and more influential than others and would often succeed in preserving their influence and prestige over successive generations; and, fourth, the fact that the population of each village consisted of a number of lineages divided into different clans.

The existence of several clans was not itself the starting point. Had it been, one would expect the number of sfūf in each village to correspond to the number of clans. This was not usually the case. At Ath Hichem, where Bourdieu carried out his fieldwork, there are only two iderman and the two sfūf do indeed correspond to them. But the multiplication of iderman beyond the number two did not usually entail the multiplication of the sfūf. The important village of Taourirt n’Ath Menguellat, about three miles west of Ath Hichem, has four iderman; two form one saff, the other two the other saff.37 At Ath Waaban there are also four iderman grouped politically in the same fashion, two in each saff. The saff system was essentially a binary system.

Undoubtedly there were exceptions to this rule, notably where the clans in a given village totaled that most awkward of numbers, three. In this case, internal village politics would sometimes be a three-handed game, a situation evoked by Mouloud Feraoun.38 But the saff systems in Greater Kabylia were not limited to the village but extended well beyond it, and at all levels above the village these systems were invariably two-party systems. It is for this reason that I believe that it is a mistake to try to explain the existence of saff divisions by the prior existence of clans.

The starting point for the existence of the sfūf was the fact that each Kabyle village and, for that matter, each Kabyle ‘arsh governed itself through its jema‘a – that is, by a public meeting. Government by public meeting presupposes the existence of parties. It is impossible to sustain in their absence.

Those observers of Kabyle political organisation such as Masqueray who have tried to make sense of it without travestying it have often been driven to resort to the analogy with the city states of classical antiquity, Athenian democracy or republican Rome. This analogy they have invoked rather than explored and justified in depth, however, and there has been another analogy available to them which they have never used. This is the analogy with the one democratic state in the modern era of which it has been true to say, since its constitution, that it has been governed by a public meeting. For, mutatis mutandis, the intrinsic logic of this form of government is the same in whatever conditions it develops.

The logic of the British example of this form of government was described four years before Hanoteau and Letourneux published their study of Kabylia, by Walter Bagehot:

… we are ruled by the House of Commons; we are, indeed, so used to be so ruled, that it does not seem to be at all strange. But of all the odd forms of government, the oddest really is government by a public meeting … Nobody will understand Parliament government who fancies it an easy thing, a natural thing, a thing not needing explanation … It is a saying in England, ‘a big meeting never does anything’; and yet we are governed by the House of Commons – by ‘a big meeting’ … The House of Commons can do work which the quarter-sessions or clubs cannot do, because it is an organised body, while quarter-sessions and clubs are unorganised … At present the majority of Parliament obey certain leaders; what those leaders propose they support, what those leaders reject they reject … [T]he principle of Parliament is obedience to leaders … If everybody does what he thinks right, there will be 657 amendments to every motion, and none of them will be carried or the motion either … The House of Commons lives in a state of perpetual potential choice; at any moment it can choose a ruler and dismiss a ruler. And therefore party is inherent in it, is bone of its bone, and breath of its breath.39

There is no question of the Kabyle jema‘a being generally analogous to the British House of Commons.40 Where the jema‘a was an assembly of all adult males, it evidently differed from the House of Commons in being a form of direct, not representative, democracy. And, where the representative element obtained, through the agency of the temman, the conception of representation which was operative in the Kabyle case was, as I have already insisted, very different from that traditionally underlying the position of a British MP. Moreover, a Kabyle jema‘a was not primarily an elective body. The emphasis which Bagehot placed upon the elective functions of the House of Commons has little application to the Kabyle case in the pre-colonial period. The jema‘a did, it is true, elect the amīn and the other officers, but the powers delegated to them were very modest compared with those entrusted by MPs to ministers.

But in one cardinal aspect at least the analogy holds. In both cases it is the deliberative assembly which is supreme within the form of government in question.41 And for it to preserve this supremacy, it needs to be organised. The diversity of points of view which obtain within it has to be controlled and transcended by the existence within it of organised political followings, few in number, practising obedience to their leaders, by means of which coalitions of interests can be constructed which enable debate to focus on a limited range of options, if not, as often enough is the case, no more than two, pro and contra. Only in this way can minds be concentrated sufficiently for debate to give rise to the necessary decisions. A ‘public meeting’, even one which styles itself the National Assembly, which is in reality no more than a talking shop because the business of governing is being tended to elsewhere, need have no limit on the number of ‘parties’ it contains. But a ‘public meeting’ which governs must take decisions and often hard decisions at that and will therefore tend to reduce the number of parties it contains to two. It is in this sense that the logic of the Kabyle jema‘a and that of the British Parliament in its historic hey-day are the same. In each case, ‘party is inherent in it, is bone of its bone, and breath of its breath’. And in each case the party system is essentially a two-party system.42

It says much for the broad-mindedness and clarity of vision of the nineteenth-century French ethnographers that they recognised the Kabyle sfūf for what they were, for they were parties very unlike those with which most Frenchmen would have been familiar.43 They most certainly did not embody and canvass opposed visions of society or mutually exclusive constitutional conceptions, as French political parties had done for most of the time since 1789. Like the English parties from the Hanoverian succession in 1714 to the 1832 Reform Act, they took the general constitutional framework of politics for granted, as their common ground, and the structure of society as given and immutable. And, like them, they articulated differences of interest and opinion within one and the same class, not a division between classes.

What the nineteenth-century ethnographers were disposed to refer to as the ‘democratic republics’ of Kabylia were based on very different principles from the democratic republics of the world of nation-states. It is in part for this reason that the nineteenth-century view of the matter was abandoned by Bourdieu and others. Kabyle political organisation was not based on the philosophy of the Rights of Man, or the abstract democratic principle of universal suffrage, or even universal adult male suffrage. In addition to women (who were answered for by their menfolk), two categories of the population were excluded from participation and representation within the jema‘a: the hereditary saintly lineages (imrabdhen) and the aklan, literally ‘the blacks’ – that is, those families which gained their livelihoods from practising despised specialist occupations (butchers, grain-measurers, musicians) and whose disreputable professions and consequent status were conceived as the product of slave descent.

Neither the imrabdhen nor the aklan were regarded as leqbayel. A Kabyle was, by definition, a man of honour and a man of honour was by definition a man who owned land, carried arms and was, in contrast to both religious and profane specialists, a rounded man of parts, argaz lkamel, ‘the accomplished man’,44 able to turn his hand to a wide variety of tasks, ploughing, house-building, trade, war and politics.

Because the maraboutic and aklan elements of the population were a very small minority, Kabyle political organisation had the appearance of democracy: the enfranchised population was the vast majority of the adult male population as a whole. But the jema‘a was, nonetheless, an assembly of land-owners who bore arms. The division within a Kabyle jema‘a between rival sfūf was, therefore, not the political form of a class division. Like the British parliament before 1832, only the landed interest was represented in it. (In neither case did the franchise exclude all commercial and manufacturing interests, but it did exclude commercial and manufacturing interests disconnected from landed property.) The basis of the opposition between the sfūf was therefore not ideology nor class conflict, but the rivalry between the leading families in each village, a rivalry which, whenever the interests of these families inclined them to favour opposed courses of action, expressed itself in differences over policy.

What gave these differences a stable and enduring form of expression in the saff system was the fact that each Kabyle village included a number of clans inhabiting, at least originally, distinct parts (quarters) of the village. The constituent unit of a Kabyle saff is therefore a quarter, thakhelijth, of a village, whether this is occupied by a single clan or by several. The clan division is politicised where there are only two or three clans in the village. Where there are four or more clans, the clan division is not politicised but transcended by the politicisation of the division of the village into ikhelijen. The stable basis of allegiance to a village saff is therefore not kinship but residence, not adrum but thakhelijth.

This state of affairs gave the system of saff competition at village level both a measure of stability and a measure of fluidity or uncertainty. Because the base of a saff is identified with a particular quarter of a village, it has a stable existence over time, so that the replacement of a leader from one of its families by another from a different family will not normally disrupt the lines of saff allegiance and division within the village. On the other hand, the fact that allegiance to a given saff is, for many families, primarily a function of mere residence means that within each saff there will be a potentially floating element: the stable core of the saff will be composed of a minority of leading families and their close kinship relations, but other lineages in the quarter only loosely related, if at all, to those which make up this core will be susceptible on occasion to overtures from the other saff. Within the Igawawen thaddarth, then, there is a floating vote and it was this which enabled saff X to gain the ascendancy at one moment and saff Y to gain it at another.

It is this which explains the fact, reported by Devaux and confirmed by Hanoteau and Letourneux,45 that at any one time the sfūf were manifestly unequal in strength. It is true is that this inequality at any one moment can be said to have masked an underlying equality over time: the minority saff at one point could usually expect to be able to become the majority saff at some future point. But the fact of inequality mattered politically: the deliberations of the village jema‘a on controversial matters of policy would be dominated by the majority saff of the moment.

That this was the way things worked was obscured by the fact that all decisions of the jema‘a were formally agreed by all present. But it is a mistake to suppose that a Kabyle jema‘a was subject to a requirement of real unanimity. This was a matter of form rather than substance.

The sjem (parliament) of the Polish szlachta (nobles) in the seventeenth century was subject to a real unanimity requirement. Every deputy possessed what was known as the liberum veto (the freedom to forbid) and this was a real veto. A deputy exercised it by the simple device of uttering, in respect of any piece of legislation he disliked, the words ‘nie pozwalam’ (‘I do not allow’), and that was that. The spirit of liberty was kept alive by such means and successive attempts to make the Poland of the nobles into a governable and defendable state got nowhere.46

Any Kabyle man could object to a proposal in the jema‘a. And there was no question of a majority riding roughshod over the minority with impunity, as happens as a matter of course in modern parliaments. But there was also no question of a measure or a course of action upon which a large majority was agreed being prevented by an obstinate handful (which is exactly what used to happen in Poland). No one had a veto. An objection was not the end of the matter. It simply prolonged the discussion or caused it to be deferred while the necessary negotiations went on in the Kabyles’ equivalent of the ‘corridors of power’. There was therefore no requirement of true unanimity, of all being of one mind. What was required was that the minority accept the decision even though they had disagreed with it. The customary form of general acceptance therefore masked the political fact that one point of view had prevailed over another. This formal requirement gave the advocates of the majority point of view an interest in moderating their own proposals in order to secure the minority’s consent. When the majority failed to do so, the conflict between the two parties would rapidly burst the bounds of the village, with possibly calamitous consequences.

The danger that the majority party in the British Parliament may abuse its power is warded off by the rule that the composition of the House of Commons must be renewed at regular intervals by general elections in which the positions of majority and minority are liable to be reversed. Liberty in the British system, freedom from arbitrary rule, is (in principle) safeguarded by the fact that the result of every election is uncertain.47 But the jema‘a of a Kabyle village is not an elected body. There is no mechanism to ensure that the balance of forces within it may change at regular intervals. The solution which the Kabyles found to this problem, the defence they possessed against the danger of the despotism of the majority, lay in the fact that the saff division within each village was not self-contained but part of a far wider saff division embracing the ‘arsh, the confederation (where this existed) and beyond. This has been simply overlooked by Bourdieu and Favret, who both suggest, quite mistakenly, that saff divisions obtained only ‘at all levels below the tribe’.48 But it was recognised by Hanoteau and Letourneux, who, while noting the existence of a formal unanimity requirement,49 also observed that:

each village, with very few exceptions, is divided into two sfūf, which are rarely equal in number or in means … The weaker party, if it was abandoned to itself, would be incessantly prey to the law of the stronger or obliged to forsake the region … To counter these dangers, it is naturally led to seek the alliance of one of the sfūf of the neighbouring villages. The range of the saff expands in this way from one place to the next, extends to the tribe, to the confederation and even to outside tribes, in a vast radius.50

This observation is true in part and in part very misleading. The misleading element concerns the dynamics of saff politics on the extended stage. Hanoteau and Letourneux offer a bottom-up view of these dynamics: each saff at village level is motivated by fear of its rival at this level and therefore looks for support in neighbouring villages; thus are the sfūf constituted at ‘arsh level and thus are they constituted at levels above the ‘arsh. I believe this to be the opposite of the truth and that the sfūf were constituted from the top down. A village saff was certainly linked to the sfūf of other villages and such linkages certainly provided its main defence against the despotic impulses of its local rival. But it did not effect this linkage for itself, of its own volition; it was linked to other sfūf by a force outside and above itself. This can be seen if we consider the saff division at the first level above that of the village, that of the ‘arsh.

At the level of the ‘arsh, as at all other levels above the village, the sfūf were invariably two in number and were often identified by names which appeared to have no political content whatsoever, names which were geographical or topographical terms employed apparently as mere metaphors to express the fact of binary opposition. The sfūf of the Ath Wasif were known as Isherqien (‘the easterners’) and Igherbien (‘the westerners’), while those of the neighbouring Ath Boudrar were known as Ilemmasen (‘those of the centre’) and Iqarnien (‘those of the edges’).51 In other ‘aarsh, the two parties were sometimes called after their current leaders. According to Hanoteau and Letourneux, this was the case in ‘arsh Iwadhien of the Ath Sedqa confederation, where the two sfūf were known (c. 1870, at any rate) as saff El Hadj Boudjema‘a and saff Ameur n’Ath Amara.52

A fourth possibility was and still is exemplified by the Ath Yenni, who are divided into the Ath Yahia and the Aâruren, the two sfūf being represented in each of the six lay villages of the ‘arsh, incorporating one or another of the ikhelijen of each village, as follows:

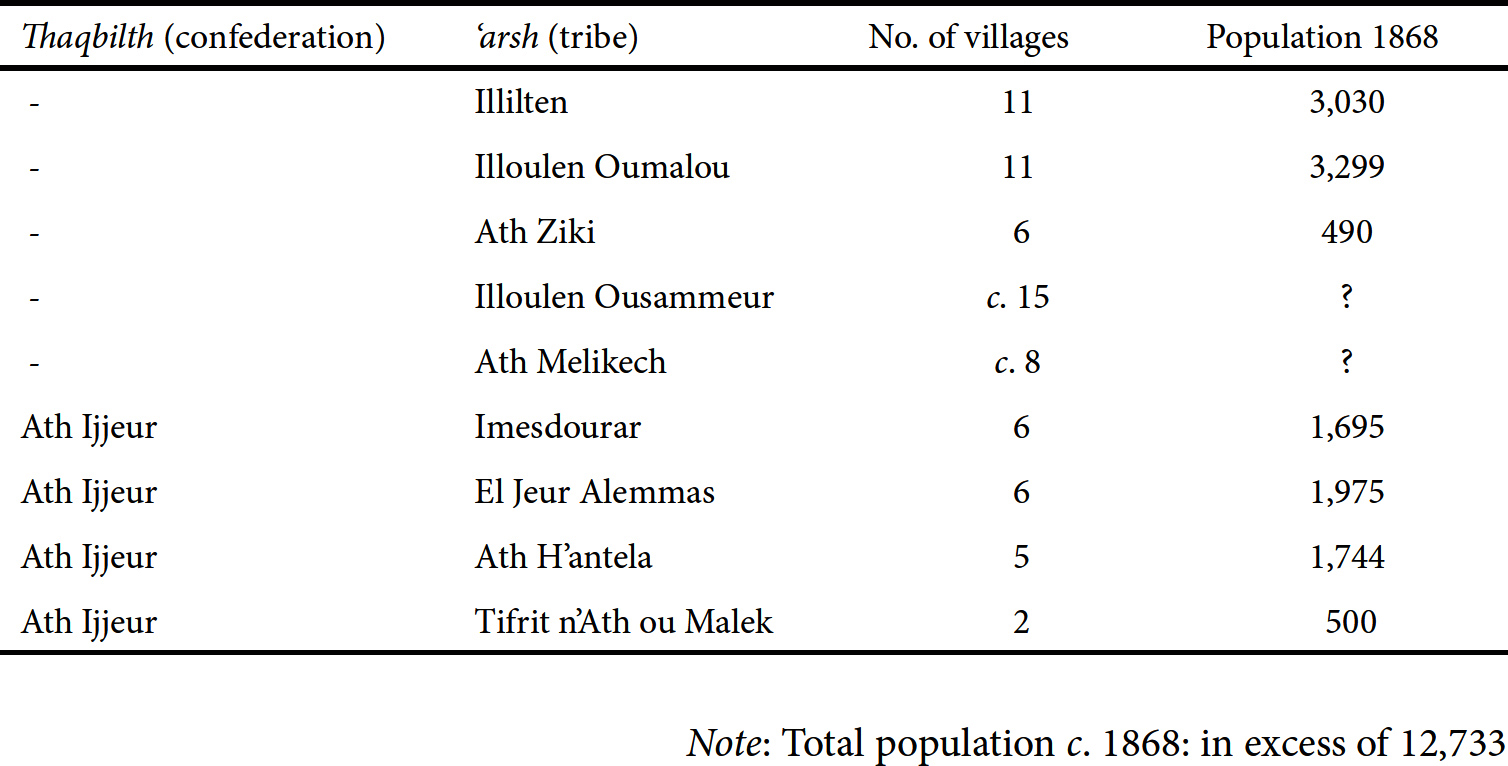

Table 4.1: Saff divisions of the Ath Yenni

We can see from this that the saff division within the ‘arsh is an extension of the saff division within the village of Taourirt Mimoun. This is explained by the fact that Taourirt Mimoun has long been considered the ‘capital’ or centre of the Ath Yenni, the seat of many of its oldest and proudest families.53 It was a party division between the ikhelijen of this leading village which organised the pre-existing divisions in the five other lay villages into a stable two-party division at ‘arsh level (inducing the three ikhelijen of Ath Lahcène to align themselves on a binary basis in the process, incidentally). It did this through the medium of the jema‘a of the ‘arsh.

When considering the role of the jema‘a in Kabylia, it is easy to concentrate exclusively upon the thijemmu‘a of the village and to forget that in the pre-colonial period, each ‘arsh also had its jema‘a, composed of the umanā’ (plural of amīn) of its constituent villages and sometimes one or two other ‘uqqāl per village in addition.54 Since we possess not one description of a jema‘a of an ‘arsh in session, we do not know for certain what business it transacted. We do not even know how often such jemāya‘ met, or where. But we know that markets in Kabylia were almost invariably attached to particular ‘aarsh, so that the organisation and safeguarding of these markets is likely to have been an issue of regular business for the jema‘a of an ‘arsh to consider. The safeguarding and promotion of trade outside Kabylia and the protection of members of the ‘arsh when away from home, in Algiers or when trading or peddling or engaging in seasonal labour in the Algerian interior, are also likely to have been matters for discussion and collective decision at ‘arsh level in at least some cases. Above all, the question of relations with neighbouring ‘aarsh is likely to have been a perennial item on the agenda (in part because it would often have been intimately connected with the question of safeguarding the local market). It is probably the last of these issues which tended to generate the most controversy within a Kabyle ‘arsh.

Every Kabyle ‘arsh has at least two, often four and sometimes five or more ‘aarsh for its immediate neighbours. The Ath Yenni share boundaries with six: the Ath Ousammeur and the Aouggacha of the Ath Irathen confederation to the north and north-east, the Ath Menguellat of the confederation of the same name to the south-east, the Ath Wasif of the Ath Bethroun confederation (to which the Ath Yenni also belonged) to the south, the Aouqdal of the Ath Sedqa confederation to the south-west and the Ath Mahmoud of the Ath Aïssi confederation to the north-west: six ‘aarsh as neighbours, belonging to and so implicating five different confederations. The Ath Menguellat share boundaries with seven other ‘aarsh: Aouggacha, Ath Yenni, Ath Wasif, Ath Attaf, Aqbil, Ath Bou Youcef and Ath Yahia. The Ath Boudrar share boundaries with eight: the Ath Bou Akkach, Ath Wasif, Ath Attaf, Aqbil, Ath Bou Youcef and, south of the Jurjura watershed, the Imecheddalen, Ath Wakour and Ath Qani.

It follows that the question of relations with one neighbour often if not invariably raised the question of relations with other neighbours and there can be little doubt that those who supported good relations with neighbour X would on occasion find themselves at loggerheads with those who had a vested interest in good relations with neighbour Y (or Z, etc.), whenever the two were mutually exclusive, which was not infrequently the case. It seems likely, then, that it was arguments of this kind which constituted the staple subject matter of saff politics at the level of the ‘arsh and that, where one village was accustomed to provide the political leadership of the ‘arsh as a whole, the division of opinion within this village on such matters was the factor organising the saff division within the ‘arsh as a whole.

For the pre-eminent position of Taourirt Mimoun amongst the Ath Yenni was not at all unusual. In many other ‘aarsh, one village held a similar ascendancy. Among the Ath Mahmoud, it was Taguemount Azouz; among the Ath Boudrar, Ighil Bouammes; among the Ath Menguellat, Taourirt n’Tidits; among the Illilten, Tifilkout; among the Ath Fraoucen, Jema‘a n’Saharij; among the Ath Yahia, Taqa; and so on.

So, among the Ath Yenni, the names of the sfūf are not mere arbitrary conventions. They reflect the constant political fact of Taourirt Mimoun’s pre-eminence within the ‘arsh and the historical fact that saff politics in the Ath Yenni originated in and radiated out from this pre-eminent village. It is probable that comparable, if different, facts are similarly reflected by the names of the sfūf in other ‘aarsh.

Why should saff politics among the Ath Wasif have been an affair of ‘easterners’ and ‘westerners’? Let us consider the evidence from a map of the area (see Map 4.1). The Ath Wasif are settled in seven villages on two parallel ridges running north from the main Jurjura range (see bottom left hand corner of Map 4.1). Five villages are situated on the western ridge, the other two on the eastern ridge. The western villages (Ath Abbas, Zoubga, Ath Bou Abderrahmane, Tikidount, Tiqichourt) share their ridge with three villages of the ‘arsh Ath Bou Akkach (Zaknoun, Ath Sidi Athmane and Tiguemounin), which are located to the south and higher up, closer to the main ridge of the Jurjura. Moreover, the local market, Souq el-Arba‘a n’Ath Wasif, is located in the valley at the western foot of the western ridge (to the south-west of Tiqichourt), and is the point of contact for the Ath Wasif, the Ath Bou Akkach and the ‘aarsh of the Ath Sedqa confederation immediately to their west. The two villages of the eastern ridge, Ath Eurbah and Tassaft Waguemoun, share this with three Ath Boudrar villages (Ath Ali ou Harzoun, Ighil n’Tsedda and Bou Adnane) which are similarly located higher up the ridge to the south, while to the north of Ath Eurbah the ridge terminates in the large mountain outcrop on which the Ath Yenni villages are situated. Ath Eurbah and Tassaft are some way from Souq el-Arba‘a and their inhabitants are much more inclined to frequent Souq el-Jema‘a, the market of ‘arsh Aqbil in the valley immediately to their east, traditionally the main commercial point of contact for the Aqbil, Ath Boudrar, Ath Attaf and Ath Menguellat.

The facts of geography suggest that Ath Eurbah and Tassaft Waguemoun needed to live on terms of good neighbourliness with the Ath Yenni and the Ath Boudrar, while the five other Ath Wasif villages were less concerned about this and more concerned with their relations with the Ath Bou Akkach and the ‘aarsh of the Ath Sedqa confederation and could afford to indulge in occasional hostilities with the Ath Yenni. And in fact the oral traditions of the Ath Yenni are studded with references to hostilities with the Ath Wasif and especially with the village of Ath Abbas,55 which faces the Ath Yenni across the intervening Asif n’Tleta valley.56 We can therefore see how the eastern and western villages of the Ath Wasif would have had different and potentially conflicting priorities in their external relations. Moreover, the eastern villages were latecomers to the ‘arsh; Ath Eurbah and Tassaft Waguemoun originally belonged to another ‘arsh, the Ath ou Belkacem, which disintegrated or was dismembered by its neighbours at some point in the mid-eighteenth century.58 (The other villages of this ‘arsh, Takhabit and Ath Ali ou Harzoun, were incorporated into the Ath Yenni and the Ath Boudrar respectively at the same time that Ath Eurbah and Tassaft Waguemoun were incorporated into the Ath Wasif; in this process, Takhabit moved closer to the rest of the Ath Yenni and changed its name to Taourirt el-Hajjaj.59) It seems likely that the incorporation of the two new villages from the eastern ridge transformed the internal politics of the Ath Wasif and precipitated a new line of saff cleavage.

Map 4.1: The Ath Wasif villages.57

There are accordingly strong grounds for thinking that the names of the sfūf of the Ath Wasif were not at all mere conventions, borrowed arbitrarily from topography in order to express an abstract impulse to binary opposition bereft of moorings in material circumstances and historical events. They directly expressed the substance of what was (or, at a critical period, had been) at issue in the main disputes within the ‘arsh.

The same is very probably true of the Ath Boudrar. Here the saff division was between ‘those of the centre’, Ilemmasen, and ‘those of the edges’, Iqarnien. Once again, this may sound like a purely arbitrary choice of topographical terms employed in order to express an abstract and unexplained impulse to dualistic organisation. But, if we take the trouble to look at the geography and history of the Ath Boudrar, we shall see the matter in a very different light.

Map 4.2 shows the geographical situation of the seven Ath Boudrar villages and their immediate neighbours. The core villages of the ‘arsh are Ighil Bouammes60 and Tala n’Tazart, situated on the central ridge, and Bou Adnane and Ighil n’Tsedda (which was originally part of Bou Adnane) on the western ridge. The other villages of the ‘arsh were all incorporated later than these four. To the north, Ath Ali ou Harzoun was added from the defunct Ath ou Belkacem. To the south-east, Darna originally belonged to the Ath Attaf,61 whose two remaining and unusually large villages, Ath Saada and Ath Daoud,62 dominate the ridge on which Darna is situated. As for Ath Waaban, located in a large valley even further to the south-east, this was founded by migrants from the ‘arsh Ath Wakour south of the watershed and was almost certainly the last village to be incorporated into the Ath Boudrar.64

Map 4.2: The villages of the Ath Boudrar and their western and eastern neighbours.63

Now, Ighil Bouammes, whose name means ‘the ridge of the centre’, has long been regarded as the leading village of the Ath Boudrar. It has been extremely important in the modern era,65 but there is nothing new about this. In 1852, the French recognised as Bachagha of the Jurjura a certain Sid El-Djoudi, a marabout from Ighil Bouammes,66 on whom they initially relied in their dealings with the Igawawen prior to the military conquest of what the colonial cartographers called ‘la Kabilie indépendante’ in 1857.67 As for Ath Ali ou Harzoun, it was the largest village of the ‘arsh c. 1868, with 1,400 inhabitants to Ighil Bouammes’s 1,344 according to Hanoteau and Letourneux, and far more than either Darna (618 inhabitants at that date) or Ath Waaban (400).68 And there is evidence from several sources that it was far from enthusiastic about being incorporated into the Ath Boudrar.

The first serious investigation of the Jurjura after the military conquest of 1857 was undertaken by Devaux, who reported in 1859 that

the Aïth Ali-Ouarzoun [sic] have always made a show of staying aloof from the new tribe which events had forced them to adopt. Very often they have protested, arms in hand, against the measures taken by the Aïth Boudrar.69

Moreover, he observed, the ikhelijen of Ath Ali ou Harzoun, whatever their differences amongst themselves, all belonged to the same saff within the ‘arsh, which was most unusual.70 This information was noted by the French authorities. With the generalisation of the douar as the basic unit of the colonial administration of the Muslim population in the Algerian countryside in the 1870s,71 the ‘arsh Ath Boudrar became the ‘douar Beni Bou Drar’ (or ‘douar Iboudraren’). The qā’id of the douar was invariably from the Aït Kaci family of Ath Ali ou Harzoun.72 In other words, having played the Ighil Bouammes card before 1857, the French decided to play the Ath Ali ou Harzoun card thereafter, these being the two main options available to them in the douar in question.

The evidence strongly suggests that the incorporation of Ath Ali ou Harzoun into the Ath Boudrar following the disintegration of the Ath ou Belkacem set up a new basis for saff conflict within the ‘arsh, and that Ath Ali ou Harzoun was the headquarters of the saff of ‘the edges’, while the saff of ‘the centre’ had its headquarters in Ighil Bouammes. The political history of the Ath Boudrar since the middle of the eighteenth century was, in its foundations, an affair of ‘core’ and ‘periphery’, just as that of the Ath Wasif was an affair of ‘westerners’ and ‘easterners’. The saff division among the Ath Boudrar came to be based on this fact and the names of the two sfūf bore witness to it.

The existence of sfūf at the level of the ‘arsh was not at all the product of an abstract imperative impelling Kabyles to equip themselves with some kind of ‘dualistic organisation’ as the unexplained emanation of an idiosyncratic psychology.73 It was the product of the entirely material and straightforward fact that Kabyle ‘aarsh decided their policy in public meetings, which necessarily engendered a two-party division, and of the particular and equally material facts of geography and history of each ‘arsh, which determined the particular ground and character of the party division in each case. The ground of the saff division varied from one ‘arsh to another, but in each case had its source in the particular history of the ‘arsh concerned.

The saff division at the level of the ‘arsh was a factor in the stable government of the constituent villages, because it was what constituted the ikhelijen into parties. I have suggested that the ikhelijen were the sfūf, at village level. This formulation of the matter, employed for brevity’s sake, simplifies the actual reality. The villagers at Ath Waaban, for instance, do not refer to the Ath Tighilt and the Ath Wadda as ‘sfūf’. They refer to them merely as ‘ikhelijen’. They do so while freely admitting that village politics is essentially grounded on the long-standing opposition of the two. What makes a thakhelijth into a saff or into a component part of a saff is the fact that it is aligned with the ikhelijen of other villages in a wider arena of political activity.

This usage is not universal. The exact opposite of it is also encountered in Kabylia. According to Genevois, the village of Taourirt n’Ath Menguellat consists of four iderman grouped in two ‘sfūf’.74 While the people of Ath Waaban refrain from describing their ikhelijen as sfūf, their counterparts at Taourirt do not bother to describe their ‘sfūf’ as ikhelijen.

Part of the explanation of this variation in usage lies in the fact that, whereas Ath Waaban has historically been a marginal village of the Ath Boudrar, Taourirt has historically been the leading village of the Ath Menguellat.75 The division between the ikhelijen at Ath Waaban has been fully politicised only when the saff division at the level of the ‘arsh has been galvanised by some fresh controversy.76 But, in the leading village of an ‘arsh, the saff division would be permanently alive, if only simmering for much of the time. While the quarters of Ath Waaban are only potential and occasional sfūf, those of Taourirt are permanently conscious of their partisan character because they are leading components of the two sfūf at ‘arsh level.77

The two usages, however contradictory in appearance, are therefore consistent with and reflect the fact that it was the saff division at the level of the ‘arsh which organised the saff division at the level of the village. And in this we can see one of the major respects in which the ‘arsh was necessary to its constituent villages. It provided a wider political framework which was conducive to stable government at village level, because, by organising the saff division, it facilitated the provision of political outlets to the feuding impulses of the clans in each village. Its ability to do this was grounded in the common interest which its constituent villages had in the ‘arsh, in that the ‘aarsh not only guaranteed the territorial integrity of their respective villages but also were the crucial agents in the system of distribution and exchange of goods within the region, as the organisers and guarantors of markets. Among the Igawawen, the ‘aarsh also organised caravans for external trade and ‘arsh solidarity underpinned the ventures of individual merchants and pedlars dans le pays arabe.78

Were it not for the ‘arsh, there would have been no sfūf in the proper sense of the term. And were it not for the sfūf, politics in a Kabyle village would have been mere clan politics – that is, the primitive politics of kinship antagonisms – and the large, complex, thaddarth of the Igawawen would have been ungovernable and would not exist. And the political history of modern Algeria would be other than it is.

But while the ‘arsh level was, arguably, the crucial level for the constitution of saff divisions, these divisions also existed at levels beyond the ‘arsh.

As we have seen, Hanoteau and Letourneux reported that the range of a saff extended ‘to the confederation and even to outside tribes, in a vast radius.’ The failure of subsequent writers to pay attention to this observation is not the least remarkable aspect of the literature on Kabylia over the last 140 years.

The confederation, thaqbilth, does not seem to have been an important level in itself in saff politics. The raison d’être of a thaqbilth was essentially defensive: a group of adjacent ‘aarsh having formed a confederation for purposes of collective security in the military sphere, the only decisions taken at thaqbilth level would be those of war and peace and the thaqbilth did not normally possess a regular jema‘a like that of the ‘arsh or the village. Moreover, it should be remembered that many Kabyle ‘aarsh did not belong to a thaqbilth but were entirely independent. By and large, those ‘aarsh which were linked to others in a thaqbilth either were fairly small or inhabited territory which could not be easily defended, or both. The institutionalised link with their neighbours thus furnished indispensable guarantees for their strategic position. This was clearly the case of the ‘aarsh of the Ath Bethroun confederation, but also of those of the Ath Irathen, the Ath Ijjeur and the Ath Jennad confederations. Larger ‘aarsh, such as the Ath Fraoucen or the Ath Ghoubri, or those inhabiting an extensive or easily defended territory, such as the Illilten and the Ath Itsouragh, had no need to belong to a thaqbilth and did not do so.

This modest estimate of the political significance of the thaqbilth admits of two exceptions. The confederations of the Ath Irathen and the Ath Bethroun appear to have possessed considerably more political cohesion than any of their counterparts, for they proved capable of collectively addressing and dealing with a major issue of a non-military character. At some point after 1737 but before 1749, the Ath Irathen decided to abrogate Quranic law in the matter of female inheritance. They resolved that henceforth the right of females to inherit landed property, enshrined in the Sharī‘a, would no longer be recognised and that landed property, as distinct from movable goods, could only be inherited by male heirs. In 1749, the Ath Bethroun followed suit.79 There are no recorded instances of other confederations taking similar decisions; the Ath Irathen and the Ath Bethroun appear to have been exceptional.

Devaux was aware of the remarkable nature of the Ath Bethroun. He reported that they considered themselves the heart or core of the Igawawen (‘le coeur des Igawawen’) and that their qawānīn were ‘very severe’ and observed ‘with a rigour without equal among their neighbours’.80 He also gave details of the saff division among them.81 According to him, this was a division between ‘sof Cheraga (de l’est) et sof R’raba (de l’ouest)’ and obtained not only amongst the Ath Bethroun but also amongst the other Igawawen to their east (which he presented as independent tribes, but which Hanoteau and Letourneux reported as forming the thaqbilth of the Ath Menguellat, a usage I have followed in Table 4.2).

Table 4.2: Saff divisions of the Igawawen

(mid-nineteenth century), after Devaux

If we substitute the Kabyle versions of these terms, properly spelt, we have saff Isherqien and saff Igherbien. It is possible, then, that the saff division among the Ath Bethroun was an extrapolation of that of the Ath Wasif. The fact that the decision of 1749 was taken at an assembly held in the territory of the Ath Wasif 82 lends support to this hypothesis. And if the saff division at the level of the thaqbilth Ath Bethroun originated in this way from that of one of its constituent ‘aarsh, it seems equally possible that the saff division amongst the other Igawawen ‘aarsh listed above originated in the same manner, as an extension of the saff division within the Ath Bethroun, a probability which would lend serious credence to the latter’s claim, reported by Devaux, that they were ‘the heart of the Igawawen’.

And this brings us to what is in many ways the most remarkable aspect of saff politics in pre-colonial Kabylia. For much more important than the existence of saff divisions at the level of the thaqbilth was the fact that the saff divisions within the constituent ‘aarsh of each thaqbilth linked up with those of other ‘aarsh outside the confederation in question. They did this in a manner which has never been properly described or explained.

According to Hanoteau and Letourneux, the ‘aarsh and confederations of Greater Kabylia – less its western-most districts, where the population had been at least partially incorporated into the political system of the Ottoman Regency – were divided into four groups by the operation of saff politics. These were:

Within each of these four groups, the sfūf of each ‘arsh or confederation were said to ‘enter reciprocally into’ the sfūf of all the others.83

There were thus four distinct and mutually exclusive saff systems. It should be clearly understood that these were saff systems, not sfūf. The four groups did not function as parties opposed to one another. There was no general Igawawen saff opposed to the Ath Irathen saff, for example. There were four distinct political systems, each of which was a framework within which wide-ranging but not boundless party conflicts were conducted.

Hanoteau and Letourneux list the membership of these groups by ‘arsh.84 If we add the figures they also provide for the population of Greater Kabylia, by ‘arsh and village, as of 1868,85 we can get an idea of the relative size and importance of the four systems.

Table 4.3: The Ath Irathen saff system

Table 4.4: The saff system of the southern Igawawen ‘proper’

Table 4.5: The eastern Jurjura and Akfadou saff system

Table 4.6: The saff system of maritime Kabylia

From this data we can see that the boundaries of the four systems coincided with those of ‘aarsh or confederations in almost all cases. The only definite exceptions were the case of the Iamrawien and that of the Ath Yenni.86 In the former case, the Iamrawien Oufella (the Iamrawien villages settled higher up the Sebaou valley) were partly in the Ath Irathen saff system and partly in the saff system of maritime Kabylia, while the Iamrawien Bouadda (‘the Iamrawien lower down the valley’) were in neither. In the latter case, the Ath Yenni was the only ‘arsh of the Ath Bethroun confederation not to enter into the saff system of the Igawawen, preferring to participate in that of the Ath Irathen instead. These exceptions to the rule can be explained by the exceptional circumstances of the populations in question.

The Iamrawien or Amrawa87 were composed originally of both Kabyle migrants from other districts and Arabic-speaking immigrants who settled in the central Sebaou valley and whom the Ottoman Regency eventually constituted into a makhzen tribe to control the lowlands on behalf of the central power. In the course of time, the Iamrawien were almost entirely Berberised and have long since been considered Kabyle. But the Iamrawien Bouadda, like the other ‘aarsh of western and north-western Kabylia, remained politically in the ambit of Algiers and outside the saff systems of ‘la Kabilie indépendante’. The more easterly Iamrawien Oufella, on the other hand, came under the influence of the independent ‘aarsh to their north and south. Those of its villages on the right (north) bank of the Sebaou, on the edge of the Ath Waguenoun’s territory, Timizar Laghbar, Tikobaïn, Tala Athman and Tamda, were drawn into the saff system of maritime Kabylia, while its villages on the left (south) bank of the Sebaou, Isikhen ou Meddour and Mekla, being in the vicinity of the Ath Irathen, came under the latter’s political influence and were drawn into the Ath Irathen’s saff system.88

As for the Ath Yenni, there is no doubting the fact that they belonged to the thaqbilth of the Ath Bethroun and were an Igawawen ‘arsh in the strictest meaning of the term. Yet, according to Hanoteau and Letourneux, they did not belong to the Igawawen saff system like the other Ath Bethroun ‘aarsh, but to that of the Ath Irathen. On this point, Hanoteau and Letourneux directly contradict Devaux who, as we have seen, gave details of the Igawawen saff system in 1859 and reported that the Ath Yenni belonged to it. Hanoteau and Letourneux do not allude to Devaux’s report, however, and give no evidence in support of their own account. If we assume that Hanoteau and Letourneux were right and Devaux simply wrong, how might we explain the Ath Yenni’s exceptional position?

The Ath Yenni are the most northerly of the Ath Bethroun ‘aarsh, and most of the north-eastern boundary of their territory abuts that of the Ath Irathen ‘aarsh of Ath Ousammeur and Aouggacha, while part of the western boundary abuts the territory of the Ath Mahmoud, one of the three ‘aarsh of the Ath Aïssi confederation which were in the Ath Irathen saff system. In addition, it is possible that the nature of the Ath Yenni’s manufacturing and commercial activities gave them an interest in Ath Irathen politics.

There is no way of telling precisely how important the manufacture of counterfeit money was to the material prosperity of the Ath Yenni.89 But they were the only ‘arsh to engage in this production and it was sufficiently important to attract orders from far away, as we have seen, and to arouse the wrath of the Ottoman authorities in Algiers, who made the trade in this commodity a capital crime. The Ath Yenni did not themselves handle the circulation of their output in Algiers and the other urban centres (Constantine, Setif, Bona, etc.); according to Hanoteau and Letourneux, they somehow managed to induce men of other ‘aarsh and especially of the Ath Bou Youcef and Aqbil to act as their intermediaries.90 But the Ottoman authorities were well aware that the Ath Yenni were the source of this commerce and were certainly concerned to inhibit it.91 Apart from putting to death the purveyors of this commodity whenever it got its hands on them in Algiers and elsewhere, however, the Regency could do nothing short of mounting a punitive expedition into the heart of Kabylia.