Chapter Five

THE TENTH CENTURY

Towns and Trade

Insofar as a century can be characterised by its archaeology, the tenth is notable for an increasing quantity of physical evidence of various sorts, not least pottery. Inorganic-(chaff-)tempered wares (though not the distinctive grass-marked Cornish vessels) were finally supplanted by fabrics which survive better in the ground, even though they may not be more serviceable in use. Not all the known pottery-producing centres were new in the tenth century, nor are the locations of more than a few of them known anyway. Nevertheless, despite the limited data-base, distribution maps of kilns, and of the pottery dispatched from them, often show differences between different areas which may be informative about other economic and social differences.

Most is known about production centres in East Anglia, where several have been found either within or immediately outside the enclosed areas of places which other evidence, such as streets and houses, shows can be termed towns in the tenth century. Whether production at Ipswich, where potters had been using ‘slow’ wheels since the seventh century, continued without interruption is not yet clear, but if so, there was not much of a hiatus, since in the Cox Lane area there was production both of the earlier ‘Ipswich ware’ and the later, fast-wheel made ‘Thetford-type Ipswich ware’. This cumbersome terminology is used because pottery made in Ipswich was very similar to the products of kilns that have been excavated in Thetford, Norfolk (5, 1). Where the new technology was first introduced is not known, but it was rapidly adopted, as the thrown pots show that the potters made little attempt to retain the earlier Ipswich-ware forms. Furthermore, the two products are not often found in the same contexts, suggesting that if ever they were in contemporaneous use, it was not for long.1

The fast wheel may have been brought to England by migrant potters, not by English potters who had seen its use abroad, or who had been told about it. Certainly a migrant potter is most likely to have been responsible for the light-coloured, red-painted and glazed pottery being produced at Stamford. These vessels are of high quality, much thinner and seemingly more attractive than the unglazed, thicker, Ipswich/Thetford wares. Red painting, using an iron solution, was practised in Germany, but the decoration at Stamford is most like that produced in northern France at Beauvais, and a potter may well have come to Stamford from there.2 The kiln complex is in the area of Stamford in which there is the possibility of a ninth-century ditched enclosure, perhaps the original focal point of the town. If so, the location of pottery-making within it around the turn of the ninth and tenth centuries is a remarkable example of a craft manufactory attaching itself to a market centre as it began to evolve from what may originally have been a Viking army base. At any rate, Stamford made rapid progress during the tenth century, as did pottery production within it, for although the red-painted wares soon ceased to be made, other kilns were turning out quantities of lead-glazed wares for the next 300 years.3

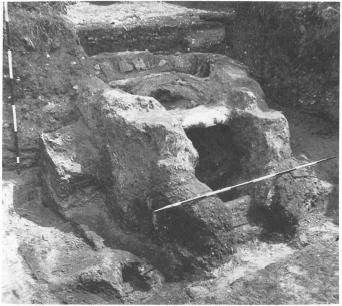

5, 1. A pottery kiln at Thetford, Norfolk, excavated in the 1950s. The ranging-rod spans the flue through which flames from the stoke-pit were drawn into the kiln; behind the ranging-rod can be seen the floor on which the pots were stacked during the firing. The floor was pierced with vent-holes to let the hot air through. The sides and top of the kiln are missing.

The Stamford pottery industry's history is very different from that of other centres. Red-painting was not adopted anywhere else, and glazing only spasmodically. Ipswich, Thetford and other kiln centres produced only unglazed wares, though with much the same range of bowls, spouted pitchers, cooking-pots, storage vessels and other household equipment. This cannot have been through ignorance of glazing's existence, as Stamford wares have been found at Thetford and other known kiln sites, as well as at many places where potting is suspected but not proven: and imported Islamic sherds found at Lincoln show that knowledge of glazing was available from other sources.4 Indeed, there is evidence of lead glaze on some locally-made sherds at Lincoln which suggests that potters were experimenting in its production. Yet even in the eleventh century, glazing was only practised at a few places, and most of those a long way from Stamford. It is as though Stamford established itself quickly—although its earliest products do not seem to have reached Thetford—and its quality kept out competition within the area over which it could be transported without unacceptable risk of breakage, perhaps fifty miles overland, as far as Oxford or Worcester, and further by river and coast (6, 4). A high-quality clay may have helped: the use of Stamford-ware crucibles and lamps even in Thetford suggests that the clays may have had particular refractory, heat-resisting qualities. Nor should the cost involved in glazing be underestimated, for it has been reckoned that a kiln load of 200 pots would have required forty-four pounds of lead. Tinkers’ scraps would not have been enough to supply this sort of quantity on a regular basis, and lead must have been brought to Stamford in bulk, presumably from Derbyshire—it is unlikely to be coincidence that considerable amounts of Stamford ware have been found in Derby. It is not easy to envisage some form of gift-exchange servicing the Stamford kilns: if the archbishop of Canterbury managed to retain possession of the Wirksworth mines purchased in 835, no reciprocal gift to him from the potters would account for the regular consignments they needed. There must have been commercial arrangements of some complexity, perhaps arranged by a kiln-owner employing potters, rather than by the producers themselves.

The list of other known kiln sites of the tenth century where wheel-thrown, mostly sandy wares were being made is almost a litany of the towns of the northern and central Midlands: Nottingham, Thetford, Norwich, Ipswich, Northampton, Lincoln, Torksey. Wasters of limestone-tempered and handmade pottery and fired daub as though from a kiln dome have been found at Gloucester, and there are wasters from Stafford. Otherwise, production in or very close to York and others is suspected but not proven. None of the products of these kilns had such a wide distribution as Stamford ware, though many are found thirty miles from their production centres, and Stafford types have been found as far apart as Chester and Hereford. Large Thetford-ware storage jars are found over a wider area than their Stamford equivalents, perhaps because they were used to transport East Anglian grain or flour.

The conclusion to be drawn from all this seems to be that pottery production can be expected to be a concomitant of places developing as markets, where at least small numbers of permanent inhabitants were not engaged full-time in agriculture, but were involved in trades such as pot-making and selling. Because of the investment that was necessary, there might already have been small-scale employers of labour. Further south in England, however, the evidence is generally different: in particular there is no trace of pot-making within the walls of London, where in the tenth century a rather thick but wheel-thrown shelly ware was almost exclusively being used.5 There is limestone or chalk in this pottery, so it could not have been made any closer to London than Greenwich. Probably it came from as far away as the Oxford area, presumably using the Thames as the main carrier.6 Surprisingly, tenth-century London seems not to have received pottery from Ipswich or the other east coast ports, nor from the Continent. Although the city's trade in pottery cannot be assumed to mirror its trade in any other product, both the distance that vessels were brought, and the direction from which they were coming, is exceptional.

There is a possibility of ceramic production in Canterbury, but the types of tenth-century pottery found in the town are not very different from those of the ninth.7 Wasters and daub have been found in a pit in Chichester, but clamp kilns nearby are dated by archaeomagnetic techniques to the mid-eleventh century. The pottery was wheel-made. These fairly recent finds may disprove earlier suggestions that both wheel-thrown and hand-formed pottery were being produced in the town in the tenth century.8 No other southern towns have yet produced tenth-century evidence of production within them or very close by, but glazed pottery was available in Winchester by about the middle of the century, and the absence of it in any quantity elsewhere in Hampshire suggests that it was being made near the town.9 Otherwise, there are some types of pottery that were probably being made at various different places, such as the shelly ‘St Neots’ types widely found north of the Thames in the south Midlands which can be attributed neither to a single manufactory, nor to manufactories specifically associated with, for instance, Oxford or Bedford. There is another type of pottery for which a fifty-mile wide distribution may be claimed, probably based somewhere in Wiltshire and serving that county and east Somerset.10 In broad terms, however, it seems that the pot-producing centres from about Suffolk southwards were not located in towns, and that most places, despite the London evidence, were obtaining a variety of different types of pot of indifferent quality made by people whose use of the wheel was intermittent and of glaze non-existent, apart from what was available in Winchester. They are more likely than their urban counterparts to have been part-time and self-employed. If this pattern is valid, there are at least two interconnected explanations of it. One is that the southern part of England had been less disrupted by Viking raids and settlements, and its traditions of pot-production were able to continue much the same as they had before, merely increasing volume of output to meet any increased demand. Further north, either there were fewer producers—Essex, for instance, seems to have used little in the way of pottery—or any existing networks were broken up: the absence of Ipswich vessels from tenth-century London may be evidence of this. Changes would have facilitated the emergence of new systems of production and supply to integrate with the places which were acquiring enough inhabitants to create a market focus. Unencumbered by traditional modes, pot production could be sited in the new markets, close to the main point of sale.

5, 2. The boat found in the marshes near Graveney, Kent, before lifting and removal to the National Maritime Museum. Most of the keel and lower planks survived: the clinker (overlapping plank) construction is clearly shown. Dendrochronology gives a felling date in the 880s for the timbers.

Distinctive in southern England are Cornish flat-bottomed pots which have handles inside raised lugs on their rims, as though they were meant to hang over a hearth from cords, which the lugs would protect from burning.11 Similar ‘bar-lug’ vessels are found in the Low Countries north of the Rhine: were Frisian traders visiting Cornwall for its tin? Lead is another English metal which may have been exploited. Metal travelling in the opposite direction included copper, for recent analysis of some from a Hampshire site, Netherton, has shown the presence in it of antimony, characteristic of the Harz Mountains in central Germany, also a likely source of silver.12 A hoard of English coins found in the Pass of Roncesvalles could indicate that gold from the Muslim world was coming from Spain,13 as perhaps was steel for the edges of sword blades and the like.

These things cannot have been carried in very large consignments because of the need to cross the English Channel in boats which could not carry heavy loads. The carrying capacity of any ship depends on how low in the water her sailors are prepared to risk her. Consequently cargo-weight estimates cannot be precise, and would depend also upon the size of the crew, but six or seven tons seems the likely viable maximum for an almost complete boat of the period found in the marshes at Graveney, Kent (5, 2). Dendrochronology on her timbers shows that they were cut in the 880s, and she was probably abandoned after some eighty-five years of use, to judge from the date of the stake to which she was tied. Although best suited for shallow waters such as southern English estuaries, her duties could have included short cross-Channel journeys carrying such things as quern-stones from Mayen, some of which were found with her, as were hops and a single northern French pottery sherd. Cargoes of medium-value goods may be indicated, but it is doubtful if she could have carried more than 300 quern-stones at a time. She had been drawn up onto an artificial timber ‘hard’ but there was no other evidence of a harbour or of shore facilities.14 Such landing-places are not easy to locate, and are a reminder that many cargoes of agricultural produce and coastally-produced salt would have been loaded onto boats without going through institutionalised ports.

Nevertheless, many of the places which can be recognised through their archaeology as developing in the tenth century had a port function. At York, the waterfront on the south bank of the River Ouse was laid out with property boundaries, and the number of finds increases, as it does also on the north side of the river in the area between the Ouse, the Fosse and the old Roman fort.15 The excavations in Coppergate have shown how the area which was beginning to be used in the ninth century was in the early tenth formed into long, narrow tenement strips divided by fence-lines and with buildings at the street frontage (5, 3). A busy community of craft workers became established, as the rubbish from the site's pits indicates. In particular, the discovery of two of the hardened iron dies from which coins were struck, together with six lead ‘trial-pieces’, from two adjacent tenements has given new insights into the production of coinage; actual minting may not have taken place at Coppergate, which may have been where dies were cut, not necessarily just for use in York. One of the lead trial-pieces is stamped with a Chester moneyer's name. It is possible that the trial-pieces were kept as a record of what dies had been approved and issued.16

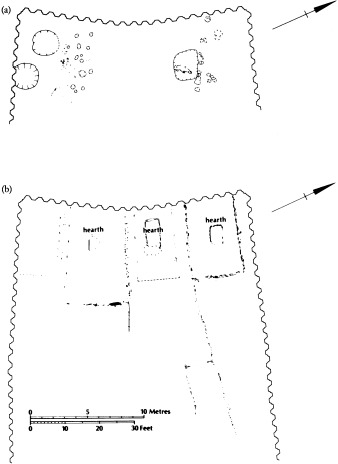

5, 3. Two of the phases at Coppergate, York, excavated by the York Archaeological Trust. In the second half of the ninth century (a), features included a glass-working furnace later abandoned and partly destroyed by a pit in which a male skeleton was found. By about the middle of the tenth century (b), the site had been divided into separate tenements with domestic hearths in each, and post-and-wattle buildings. The boundaries of these tenements were to survive for a thousand years.

One of the two York dies is associated with the currency known from the inscriptions on it as the St Peter's coinage. Some Lincoln coins have ‘St Martin’ with ‘Lincolla Civitat’. These ecclesiastical dedications may imply Church involvement in coin-production, symptomatic of good relations between the ecclesiastical and Norse authorities, which would have helped trade to continue despite political problems. An example is a York-minted coin of the 940s found in Lincoln, even though at that time York was temporarily again under a Norse, not an English, ruler. Not quite so well dated, but more remarkable, have been pieces of silk in both York and Lincoln which can be recognised from a weaving fault in them to have come from the same bale, probably an import from the eastern Mediterranean or the Near East.17 The merchant dealing in that material was able to trade in both towns.

The man responsible for the Coppergate die-production workshop was probably Ragnald, a moneyer named on many contemporary coins, who worked both for York's Norse kings and then, after 927, for the English king, Athelstan. As he was at times the only known York moneyer, it is likely that he would have been responsible for cutting the dies as well as striking the coins. He probably did not live on the Coppergate site, however, for the wicker-walled buildings and the noisome industrial and other refuse of the tenements would seem inappropriate surroundings for the residence of a man of his status. Was he ultimately responsible for the other crafts being practised at Coppergate, for there is evidence of a range of metal-working, including crucibles, moulds and an unfinished piece of lead jewellery? The raw materials for these would have been expensive and quite probably as much beyond the means of an ordinary craftsman as was the silver used in coins. Textile-working would be another industry likely to come under a financier's control when wool was brought into a town rather than spun and woven in a farmer's household from the fleeces of his own sheep, and dyes for the cloth also had to be acquired—some, such as clubmoss, were imported. Craftsmen in such industries were, like the Stamford potters, likely to be producing a better-quality product and to have more expertise, but as full-time specialists they were dependent upon others for their supply of raw materials and increasingly therefore were also losing control of the sale of their own output, and thus of its profits. Other petty craftsmen, such as the wood-turners and those making bone tools, and perhaps the stone-masons making the sculptures, could retain their independence longer.

Coinage was different from other crafts because of its centralised control, and the moneyers had to be particularly wealthy because of the bullion that they had to stock. Furthermore, theirs was the only craft that was required by law to be practised in particular places. Not only is this apparent from the mint names on many coins—though not all until the 970s—but it is also explicit in such laws as Athelstan's Grateley Decrees, which are probably based on an earlier set of instructions.18 To some extent, the volume of production and the number of licensed moneyers are likely to be a measure of a place's economic and commercial activity, with output responding to demand; but a mint may also have been a catalyst, bringing people there to acquire coins, and was not necessarily set up to meet an already existing demand. London, for instance, was far and away the largest coin-producer, but archaeology is uncertain about its speed of development as a town in the tenth century.19 Cellared buildings found at various sites cannot be very precisely dated, and the dendrochronology of a timber and clay embankment with stakes for wooden jetties at Billingsgate gives a construction date in the next century, c. 1039–40.

Although trial-pieces have been found in London, evidence about coin production like that from York is known nowhere else. General evidence of urban activity during the first half of the tenth century has come from a number of places, however. At Flaxengate, Lincoln, between the Roman fort and the river, the first road and associated buildings may have been laid out before the end of the ninth century: thereafter the road was maintained, although occasionally encroached upon, and loam layers were periodically spread across the occupation area when new buildings were required. Soon after the middle of the tenth century, if not before, the street frontage became fully occupied, with all but one of the buildings aligned gable-end to the street, where earlier alignments had been parallel to it: more houses were being packed into the space. Loam spreads continued to be dumped across the whole site, implying a single owner renting out the tenements and able to reorganise them as he wished.20 In Stamford, east of the later castle, the High Street was laid out over an area where residues show that iron-working had been taking place. Although the precise dates of each episode are not clear, the iron-working was on quite a large scale, using a fairly simple technology of roasting hearths to separate ore and slag. There was some glass-making, and pottery-making expanded, with new kiln complexes replacing that in the castle area: the new locations suggest that the potters were being kept at the margins of the town. This seems also to be the case in Thetford, where the known kilns are close to the ditch that surrounds the occupied area south of the river. Within the enclosure, there are metalled roads, buildings and pits with enough in them to indicate considerable activity in the early years of the tenth century. In Norwich also potting is only known on the fringe of the developed areas: here too there is evidence of much-increased activity from early in the tenth century, both on the south side of the River Wensum and within the enclosed area on the north which has yielded eighth-century material.21 The only kiln in Northampton is difficult to relate to a peripheral area, since it is not yet established where the periphery actually was—early defensive ditches are suggested by street lines rather than proven by discovery. It may be that Northampton had a layout that did not become formalised as early as at York or Lincoln: the buildings seem to be grouped in complexes rather than aligned on street frontages in narrow tenements.22

Within the old kingdom of Wessex, Winchester is the only town where urban growth in the first half of the tenth century can be archaeologically demonstrated: the development of extra-mural suburbs is evidence of pressure for space within the walls. The western suburb in particular has produced ninth- and tenth-century pottery and other evidence. Nevertheless, it was not until the end of the tenth century that the Brook Street site within the walls had a built-up street frontage, and there were still open spaces in which the bishop could build himself a palace in the 970s.23 It may be that the pace of the second half of the ninth century slackened off for a time in the tenth. In Chichester many pits have been excavated with pottery attributable to the tenth century and there is evidence of building, but not necessarily from an early part of the century. Canterbury also has pits and cellared buildings of the tenth century, although certainly not everywhere within the walls, and the extra-mural area near the abbey in use in the ninth century was thereafter used for agriculture until the twelfth. Elsewhere in the south, evidence of large-scale development in the tenth century is elusive, even at the larger new ‘burhs’ like Wareham or Wallingford. Exeter has a little pottery to show for the tenth century. The Itchen-side area at Southampton did not regenerate, and a Test-side replacement seems to have grown only slowly even though there is the evidence there of a ditched enclosure.24 Wessex was not developing urban centres at the same pace as the eastern side of England, despite the stimulus that might have been derived from minting of coins in many of the places that appeared in the Burghal Hidage list.

The western part of what had been Mercia seems to have had a more mixed tenth-century urban history. At Hereford, one site has produced ditches and gullies tentatively ascribed to property boundaries, but other structural evidence is lacking, and well into the tenth century the quantity of pottery found there is small.25 In the centre of Gloucester the byres and stables of the ninth century were cleared away, and at least one building with a cellar was constructed, possibly associated with replanning of the streets inside the walls. The pottery-making evidence is tenth-century, and two parts of treadle looms have been found, showing that cloth was being woven using more complex technology than that of upright looms (5, 4).26 It may well be, therefore, that Gloucester was developing as a craft-specialist centre quite early in the tenth century, for this type of loom is not readily dismantled, requires permanent housing in a wide space and demands skilled workers for its effective operation. Minting of coins was another Gloucester craft, but is only known from discoveries of the name-stamped coins in places other than the town itself. This evidence coincides with documentary evidence of royal interest in Gloucester. Worcester, however, has not produced any substantial archaeological remains concomitant with the late ninth-century charter that refers to its market, although what little pottery has been recovered comes from a wide range of sources—Stamford, Northampton, Gloucester and the Thames valley.27 The restricted, river-surrounded location of Shrewsbury has created pressure for useable space within it, causing terracing later in the Middle Ages that may have destroyed early evidence. Stafford has so far produced quantities of pottery, but not much else. None of these places is yet able to match Oxford, where street surfaces have been observed at various sites, with a coin and pottery stratified within their lowest layers which allow an early tenth-century date for their organisation to be suggested.28

Discussion of all these places shows that archaeology is beginning to be able to claim that not only did different towns differ in their course of development, but that there is a real difference between one area and another. Relatively rapid growth by and large characterises the eastern side of England, north of London. A political explanation is the obvious one, for this is also the area of the eastern Danelaw. The ‘five boroughs’, such as Stamford, are usually taken to be the centres from which Viking armies were organised, because that is what the sources imply. There are no such sources for East Anglia, but it is not a long step to associate Norwich, Thetford and others with Viking leaders such as Guthrum. This does not seem entirely adequate, however: a place needs to be more than an army camp or an administrative centre to develop the large-scale, long-term potting facilities that were established, and the tenth-century evidence can be used to argue that these places had some rôle as trading-stations already by the late ninth, particulary since most of them are on navigable rivers. They are, however, mostly well inland, suggesting that overseas commerce was a secondary consideration, and that a wide hinterland to exploit was more important. The speed of growth suggests a mobile population, perhaps forcibly settled from that hinterland, but equally likely indicative of people untrammelled by old ties as Viking disruption brought new landowners temporarily less able or less concerned to retain their tenants. So the Thetfords and the Stamfords may be a consequence of political upheaval, but as much an upheaval that caused changes in social patterns as one that led to deliberate colonisation. There is even less evidence in them of a Scandinavian population element than there is in York.

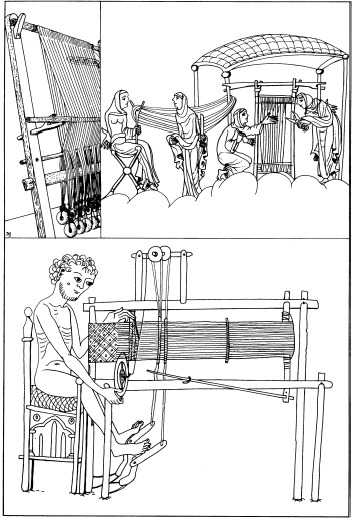

5, 4. Three different types of loom, drawn by S.E.James. A is based on a vertical loom photographed in use in Norway within the last fifty years; the clay weights are of the sort found on many early medieval settlement sites, often associated with sunken-featured buildings—one possibility is that the weaver stood on planks spanning the ‘cellar’ and that the weights dangled into the void, making it easier for the weaver to reach the top beam. B is redrawn from a manuscript and shows ladies at a beam-tensioned vertical loom, which would leave little direct archaeological record. (Although painted in Canterbury in the twelfth century, this picture copies one in a ninth-century continental book and therefore cannot be used as evidence that this type of loom could have been seen in the Norman city.) Two of the ladies hold cutting shears, the third seems to have a comb in her right hand, and the fourth holds one end of the skein of wool. C is redrawn from a thirteenth-century manuscript and shows a horizontal-tensioned loom with foot-operated treadles. Longer lengths of cloth could be produced and male weavers had taken over the craft.

Not every place which was important in the ninth century, perhaps as a religious centre, became a tenth-century town. Repton, for instance, faded into obscurity, despite having had a church, important burials and a defensive enclosure. Nor did all the places such as Witham, Maldon or Towcester mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as being fortified centres during the advance of the Wessex-based royal dynasty into the Danelaw in the first half of the tenth century inexorably develop into towns. It is also difficult to link episodes in the Chronicle to archaeological phases. At Chester, for instance, there are timber buildings with cellars which may relate to street frontages being developed outside the Roman walls. In the absence even of pottery to provide dating, is it permissible to associate these structures with the year 907, when it is recorded that Chester was ‘restored’ by the English Aethelflaed? Later on, there is pottery evidence which suggests the abandonment of the same area during the second half of the tenth century—should this be linked to the Viking raids in the 980s which are usually blamed for the decline in activity at Chester's mints at that time? Chester's tenth-century history was heavily influenced by political factors; its proximity to north Wales may have meant that silver paid to English kings as tributes by the Welsh was minted there, creating a mint output which might otherwise be taken to imply a greater level of commercial activity than actually occurred. Four tenth-century coin hoards, one also with several ingots, show that there was no shortage of silver there. Chester was a focal point in the earlier part of the century for interaction between the Vikings in Dublin and York, and the attempts by Norse kings to create an empire.29

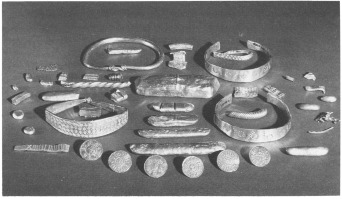

The politics of empire may well be responsible for the huge hoard of over 7,000 coins and 1,000 silver arm-rings, ingots and broken-up fragments (5, 5) deposited at Cuerdale, Lancashire in c. 905, which may represent the supply thought necessary to pay an army which was attempting to regain Dublin for the Norse after their temporary expulsion.30 It was this period which saw Norse settlement in the north, although the evidence of it comes from place-names and words rather than archaeology, apart possibly from sculpture. The ‘hogback’ stones, perhaps grave-covers, are grouped predominantly in areas in which Norse place-names are found, and may be a taste developed by people living there in the tenth and eleventh centuries. But they are not a Norse style of monument: not only are they unknown in Norway, but they are also unknown in other areas of Norse settlement, even on the Isle of Man despite its proximity to Cumberland and north Lancashire. Sculpture may also show the effect of the Norse links with Ireland through the use in the north of England of designs that seem to be Irish in origin: the ring-heads on crosses like that at Middleton are best explained in this way.31

Whatever their racial origin, the people who came into the new urban centres had to be supplied. Food requirements would have been a major catalyst for market development, with regular bulk consignments having to be available for everyday purchasing in places where little was stored. The Gloucester evidence is of decrease in stabling, and there are few indications of animals being reared within towns: bone evidence from Lincoln shows that a breeding stock was not maintained there, for the animals being eaten were nearly all fully-grown, not young stock periodically culled. Cattle, which probably account for three-quarters of the meat consumed, were mostly cows, so the bulls were being kept at a safe distance from Lincoln! The bones show evidence that the cattle had been used as draught animals, presumably for ploughing and hauling carts, but as they were slaughtered before they had reached a great age, they were probably not kept primarily for dairying. They were slightly smaller on average than those at the earlier Saxon site at Southampton, but were nevertheless reasonably robust and well developed. Similarly the sheep were mostly at least three years old when killed, but not actually very aged: although still useful for wool or milk, their meat value caused their slaughter in their prime. Pigs were also usually allowed to grow to full size before being turned into pork. Fairly similar results, from evidence spread over a longer time period, have been obtained from Bedford. It is clear that the animals were drawn from well-established herds of reasonable quality, which argues for a very adequate agricultural hinterland around these places, able to support them without distortion of existing breeding patterns. If there were diseased animals, they were at any rate not getting into the towns. Actual numbers of animals are no more known than the human population, but the Lincoln estimates based on the later Domesday figures are instructive. If the town then had some 4,000 people in it, each consuming an average of twenty-five kilogrammes of meat annually (a figure based on modern consumption levels in non-European societies), 500 cattle, 700 sheep and 400 pigs would have been slaughtered per year. Since to cull 700 sheep requires a flock of some 5,000, and each animal needs between one and two acres to graze, very large acreages become necessary just for the stock, let alone the ploughland.32

5, 5. Part of the hoard of silver coins, ingots, rings and fragments found at Cuerdale, Lancashire, in 1840. Less than a tenth of the original items now survives. Deposited c. 905, it may have been gathered in York and been in transit to pay for a Viking raid on Dublin. The deep gashes across one ingot show that it had been tested to see if it was solid metal, not just a base-metal lump gilded with silver. About half the coins are Anglo- Saxon, the rest mostly Frankish and Italian, probably acquired as loot during Viking raids in the 890s.

Unfortunately, there is less archaeological evidence from tenth-century rural sites to set against that increasingly available from towns,33 and to throw more light on the scale of organisation that was sending them its products. Most pottery dating has to be within very wide time limits, because few sites produce the quantities needed to establish a valid sequence. From evidence obtained at a few places, however, it is at least possible to postulate that considerable changes were being made in the organisation of the countryside, although whether they continued already existing trends is difficult to see. A good example is Walton, where there is sufficient pottery to show substantial occupation, with the strong possibility that the main village street was established, for gullies to mark property divisions were aligned to it. This late Saxon material overlies a mid Saxon site, but there seems to have been an interlude of at least a century between the two phases.34 What happened in the interim? Had the area generally been abandoned, or just the particular part excavated? Was the renewed occupation part of a complete refoundation, or of a long drawn-out process of expansion from a central core? It is very difficult to answer such questions without excavation of large areas, such as is now taking place in Raunds, which is demonstrating different uses at different times of quite small areas within the present-day settlement.35 Field-walking is another source of information, but leaves open the question of whether the recovery of late Saxon sherds in increasing quantities is symptomatic of increased populations, or merely of increased availability of pottery.

One major reason for thinking that village sites were being established as nucleated centres is the increase in the number of known rural churches. This is, of course, not an absolute guide, for many churches never had villages round them, but served scattered, isolated farms and hamlets spread over a wide parish. Nevertheless a church could be a focus around which a village might be deliberately planted, or might slowly develop. Many existing churches have demonstrably Anglo-Saxon styles of work surviving within them to show that their origin is at least eleventh-century: these relatively minor churches are often difficult to attribute to a particular hundred-year period. What excavations at many have shown is that below them there may survive the vestiges of an earlier, often timber-built, structure, presumably the original church building regarded as too small-scale for later requirements. This is not invariable, and sometimes post-holes may relate to scaffolding erected for the construction of the stone church. But even where no traces of timber have been found, it need not mean that none existed, for they are very easily lost to later burials and burial-vaults.

One of the best sequences has been obtained at Raunds. Here, probably by the end of the ninth century, a small rectangular timber building had been constructed ouside the existing enclosure: because the next use of this part of the site was for burials and a building that is clearly a church with nave and chancel, it is reasonable to interpret the first building as a ‘field-chapel’, used for services but not yet licensed for burial. The second building was itself replaced by a slightly larger church after about a hundred years, which also only lasted about a century and was then destroyed so that the site could be used by a secular manor house. This last stage was unexpected, for it is usually assumed that, once established, a church tends to become a fixed point for as long as there are people wanting to use it. The Raunds sequence means that even a church cannot be taken as an unchanging node within a village. It also indicates the association between landowner and church, for the first chapel was next to what seem to have been high-status buildings, and it was clearly the manorial owner who was later to build over the site without respecting the graveyard. Although such an act could have been done with communal agreement, it seems unlikely that local feelings would not have been against it. There is plenty of documentary evidence for ‘proprietary churches’, so the association with a manor house and its curtilage at Raunds is unsurprising, and indeed is still visible in very many villages and hamlets today. In some ways more interesting is that it does not appear that the site was used for burials before a church was built, and that a building that could have been a chapel pre-dates the cemetery. Since burial was one of the fees charged by the church, a graveyard was a source of revenue, and it may be that when the Raunds owner won burial-rights for his church, he was thereafter able to divert part of the fees for the interment of his tenants into his own pocket, reducing the income of the church which had previously had sole burial-rights in the area. Occasionally records exist to show the original superiority and greater authority of the earlier church in this kind of situation. The larger size of many late Saxon churches compared to the ‘proprietary’ churches is often a clue to their early status as ‘minsters’. It may just be the result of inadequate investigation, but there seems to be slightly more evidence of ninth- or tenth-century small cemeteries and churches to the north of the Thames than to the south, and it certainly seems easier to reconstruct the territories of the ‘minsters’ in the south. The older, well-established southern churches were probably able to prevent the loss of income represented by the building of ‘proprietary’ churches for perhaps a century or so after the changes in land-ownership further north had made more difficult the resistance of those ecclesiastical establishments that had survived.36

It was not only in the countryside that small parish churches were being built in the tenth century, for they are a feature also of towns, both north and south of the Thames. One of the first to be investigated was in Thetford, where foundation trenches and post-holes indicate a timber-built nave and chancel, the two elements divided from each other by a substantial screen. It was replaced after about a hundred years by a slightly bigger church using stone foundations.37 The original nave was only seven metres long, an indication of the small size of the congregation that it was to serve. Urban parish churches were often built very close to each other, so they can only have had a limited catchment area. Like their rural counterparts, they can be regarded as speculative ventures by property-owners, since many entries in Domesday Book indicate privately-held urban churches, sometimes divided between two or three owners. One apparent example is St Mary, in the Brooks, Winchester; since its nave reused the ninth-century stone building interpreted as part of an aristocratic enclave, its conversion to a church seems to indicate private ownership.38 A door in its south wall giving access to an adjoining tenement could have been to give the owner private entry, but that property does not seem to have had high-status domestic use, and the extra door cannot be used as positive evidence of proprietorship. There could be another factor influencing the choice of site, for the church is also adjacent to the small, seventh-century burial-ground whose inhabitants, from their accompanying grave-goods, were certainly high-status. It might therefore be that it was religious associations surviving from that earlier phase of use which led to the establishment of St Mary's, rather than merely expedient reuse by the owner of some of his existing property. Such instances may be unusual, and there seems no reason other than sensible exploitation of a street corner location to account for the position of St Paneras, another Brooks church, founded in the tenth century, only a few yards from St Mary's. Similarly, many churches were built near gates in a town's walls, or were even part of a gate's structure. A very different reason behind the choice of a particular site may be St Helen-on- the-Walls, York, with its mosaic head, perhaps to be associated with a cult of the Emperor Constantine's mother.39

Whereas many of the new rural churches won burial-rights for themselves, many of the urban churches did not. The difference may indicate the land-value factor, for a graveyard in a town would represent a space lost for building and renting. But here there is a difference between the north and south, for small churches in towns like Lincoln were more likely to have a graveyard than those in towns in the south, as though the greater churches in the latter were able to hold on to their rights. The same may well be true of baptismal rights, but the existence of a font can be very hard to locate. Whether owners chose to be buried in their own churches, or to be taken to some more ancient and venerable institution more worthy of their status, is another practice that may have varied in different areas. The cross-shafts, tomb-slabs and memorials in many northern churches, even in a small urban church like the recently excavated St Mark's, Lincoln,40 are an indication that the rich people who could afford such markers elected to be buried amongst their fellow-citizens, perhaps even their tenants. An elaborate stone grave-cover over a burial given a prominent position separated from other adults at Raunds indicates the same thing there.41

The Church shows another geographical division in the tenth century, the second half of which saw a major reform movement associated with Benedictine monasticism. This affected many existing churches and led to others being built, but few of the reformed houses were to the north of the central Midlands. Much patronage was extended to the new foundations and patrons, and probably others, sought to be buried at the most prestigious centres. Consequently, elaborate grave-markers have been excavated at the Old Minster at Winchester, and the few such things known elsewhere in the south of England tend to be at major churches—if not great cathedrals and abbeys, then at least older ‘minsters’. North of the Wash, landowners did not seek total separation from those of lower status as aristocracies usually tend to do, but were perhaps still using distinctively-marked burials as an assertion of their hold on newly-acquired estates because they did not yet feel secure in their possession of them.

The extent to which the Reform movement led to physical restructuring of the churches at which Benedictinism was introduced is difficult to estimate because so many of the most important have been totally destroyed. Although the ramifications of the Old Minster at Winchester have been revealed by excavation of its ground plan, showing how a complexity of chapelry was added, especially at the west end so that king and bishop could preside in splendour at services, the building could not match in width at least the New Minster, an aisled building established early in the tenth century. Nearby, recent work has shown something of its contemporary, the Nunnaminster, which was less than ten metres wide, but had substantial western apses: it was replaced, perhaps during the Reform period, by a church of much the same width but with thicker walls, implying support for an elaborate superstructure.42

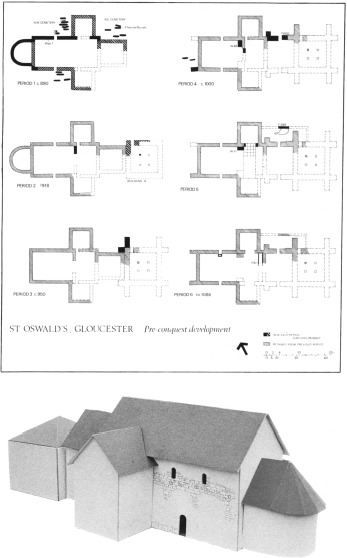

Elsewhere, the regular order of Benedictine life may be mirrored by the rectangular or square cloister attributed to Dunstan at Glastonbury, but this is far from being a complete plan. Another very important building has been found, partly still standing, at Gloucester where the core of St Oswald's Priory surely cannot be anything but the late ninth-century foundation of Aethelflaed of Mercia.43 At the east end of the original church, a separate, square building with a crypt was added early in the tenth century. The later tenth may have been when the chancel was rebuilt and the crypt building joined to the rest of the church (5, 6), but it is not possible to associate this with the Reform. Because so much is known about this movement from documents, it is tempting to ascribe to it buildings and rebuildings which are perhaps really only symptomatic of the constant process of change necessitated as much by need of restoration as by liturgical change. Nevertheless, knowledge of services and prayers helps understanding of church design: the Regularis Concordia, which laid down the rules for the Order, shows that altars were needed along the central axis-line of a church, and thus helps to explain structures like Deerhurst, Gloucestershire, with rooms over the west doors for one of the altars; another would have been at the east end of the nave and a third in the sanctuary or chancel.44 Similarly, the Maundy Thursday service required responses to be sung across the choir or crossing, and provides an explanation of the side porticuses which Deerhurst and many other churches have. Bells had to be rung, accounting for a proliferation of bell towers— Deerhurst had its porch raised, probably for this purpose. Careful excavation can reveal other features: details of the wear pattern on the floor of St Mary, Winchester, indicate that the priest took services while standing in the sanctuary, coming forward to face the congregation across the altar at the east end of the nave when he raised the Host during the Mass. It has been suggested that this is one of the ways in which the rôle of a priest can be interpreted as having been more closely integrated with his congregation than later in the Middle Ages, when the altar was against the east wall in the sanctuary so that when the Host was raised, the priest had his back to the congregation, who could see little of what was going on. In such ways the immediacy of contact between priest and people was lost.

5, 6. St Oswald's Church, Gloucester. The phase plans by C.M.Heighway show its structural development from a late ninth-century structure with western apse, north and south porticuses and square east end. Probably to accommodate the shrine of St Oswald, a square building was added and later incorporated into the rest of the church. The model, by R.Bryant, shows how it may have appeared in the second phase: the west apse is on the right. The stones outlined on the wall survive in the ruins of St Oswald's today.

The Reform movement introduced Benedictine rules of work to the inmates of its houses, and many of the finest English decorated manuscripts are a product of their labours. The Benedictional of St Ethelwold, for example, is a book of blessings, written on expensive vellum and painted in gold leaf and costly colours for Bishop Ethelwold of Winchester, its creation an act of worship to turn God's treasures into God's word, as well as to flatter the bishop's ego. Although the Reform movement promoted the writing and embellishing of books, there are decorated manuscripts of the first half of the tenth century also, so that it is an enhancement of output that is recognisable. The same is true of other ecclesiastical treasures, some surviving in church treasuries, others having been recovered during excavation. A purse-reliquary of the later ninth or early tenth century, found in a rubbish pit outside Winchester in 1976, and perhaps made in the town, can be compared with continental styles, and its function demonstrates the importance of cults of relics. It is made of gilded copper alloy, not pure gold, and this has been used to call in question whether the numerous contemporary descriptions of precious metal altars and other treasures in tenth- and eleventh-century Englishchurches are not an exaggeration of their real worth. Cast copper-alloy cruets and censers, well made but not intrinsically valuable, are further instances from he tenth century. It is probable that what survives is representative of the norm, not the exceptional, as with most archaeological artefacts, and that the purse-reliquary and other things are what would be found in many, perhaps parish, churches while the greatest treasures of cathedrals and abbeys were the ones that attracted comment. Exceptional in the way that they have survived are the vestments of coloured silks and gold thread embroidered, according to their inscriptions, for Frithestan, Bishop of Winchester from 909 to 931, on the orders of a lady named Aelfflaed, probably to be identified as Edward the Elder's queen. After Frithestan's death they seem to have been taken as an offering to the shrine of St Cuthbert by King Athelstan: owned by a bishop, probably donated to him by a queen and thought worthy of royal presentation at England's premier shrine, they must represent the reality of the finest textiles, splendid in quality and costly in material. They suggest that texts do not exaggerate too wildly in their descriptions, and that what is recovered from the ground is normally a lower stratum of craftsmanship and cost.45

This is true also of private treasures, and it is always difficult to know the extent to which discoveries of gold and silver rings and brooches, swords and knives, are representative of what existed. The tenth century was not a particularly peaceful one except in its third quarter, but rather fewer hoards were deposited during it than in the ninth: consequently less is available to demonstrate private wealth. Chance finds from random loss of notable objects are many fewer, however, and there does seem to be a real decline in the quantity of highly-decorated personalia that was worn: there are no finger-rings inscribed with a king's name, no swords with silver and gold plates. There are gold and silver arm-rings, referred to in wills, which are probably represented by the twisted rods and wires of various diameters that are known from hoards of both the tenth and the eleventh centuries, so the metals were available. These rings are like bullion stores carried on the person, rather than the filigree and niello-enhanced decorations of earlier centuries. This change suggests that the wealthy found it less important to express their status in display of objects admirable in workmanship and design, redolent of the gift-giving tradition that cemented earlier societies. Social evolution diminished the rôle of such ties.

At the same time, and over the eleventh century as well, there is evidence of increased numbers of base metal brooches. This is partly because of the towns: York, for instance, has produced many copper-alloy rings and brooches, and also some of pewter, indicative perhaps of increased availability of and demand for tin and lead. It is possible to see in these things the growth of a broad-based consumers’ market. Another type of object to consider in this context is the strap-end of cast copper alloy, tongue-shaped in the Carolingian fashion, and often of very high quality casting, but not all of these may have been for personal use: some could, for instance, have come from the straps on book- covers in church libraries. Certainly personal, however, are translucent enamel brooches, only recognised recently but clearly available in some number from the later tenth century, suggesting a taste for bright things, although the best of this effect is soon lost because the copper base tarnishes unless gilded, and ceases to reflect the light. Although most have a cross design, some have what seems to be symbol intended to ward off the ‘evil eye’: if so, they are ‘apotropaic’ in the same way as much later medieval jewellery.46

One explanation of the changing use of precious metals in jewellery could be that it was dictated by their availability, not by fashion or social evolution. The large quantities of English silver coins found in Swedish and Danish hoards of the late tenth and early eleventh centuries show that there was enough bullion coming into England to feed the mints, so that it is unlikely to have been in short supply except for temporary interludes. The degree to which coins circulated, as opposed to being used to pay taxes or to keep in hoards, is difficult to measure as there are not very many stray finds. Nevertheless, the larger urban excavations have produced enough to show that coins were available in towns, even though some have been surprisingly unfruitful: Bedford, for instance, has yielded no pre-thirteenth-century coins at all.47 Away from the towns, the evidence does not at present seem to suggest any greater usage than in the ninth century. Coins in hoards always come from a number of different mints, which is evidence that coins were acceptable no matter at which English centre they had been minted. Hoards were usually assembled by merchants travelling from place to place: such commercial interaction led to rapid intermingling of coins from different mints, a pattern also reflected by stray losses in towns. Rural losses give a slightly different picture, as coins on rural sites are rather more likely to come from a local mint than from one further away, even if the nearest was not one of the biggest mints. A silver penny found at Mawgan Porth, the north Cornish coastal site, is a good example, for it was struck at Lydford, Devon, between 990 and 995.48 People went to their nearest mint to collect their new coins and took some of them back to their villages.

Mawgan Porth is one of the relatively few excavated sites which seems to be a rural settlement of no particular consequence in the tenth century. A little more is known of higher-status rural sites, though recognition of their precise role in the hierarchy can be difficult. It is instructive to look at Portchester in this context, for the comparison that can be made between its archaeology and the written statements about it. It was listed in the Burghal Hidage, and was bought by King Edward the Elder in 904 from the bishop of Winchester. It was never a mint, however, and was not listed as a ‘borough’ in Domesday Book; by 1066, all but a small part of the estate of Portchester, probably including the old Roman fort, had passed out of royal ownership. The excavated buildings datable to the tenth century include an aisled structure, indicative of a fairly well-to-do owner, and subsequent development suggests that Portchester was indeed the residence of a substantial lord. Yet the sheer volume of finds, such as the pottery and bones, indicates that there were more people than the lord's immediate household living there, and at least one minor craft, bone-working, was being practised. The evidence is of an estate centre of some complexity and scale, but it is not possible to say from the archaeological evidence when it left royal ownership and became a thegn's property.49

The best-studied estate centre that can certainly be assumed to have been a royal one, in the tenth century if not in the ninth, is Cheddar, where the original bow-sided hall was replaced during the middle part of the tenth century by a shorter but much wider rectangular timber building, the posts of which survived for about fifty years before being replaced by another building of similar size. Other structures included a rectangular one built on unmortared stone foundations, recognisable as a chapel mainly because it underlay what were certainly chapels in later periods: there were, for instance, no burials in it, and nothing that can be seen as a font-base. Debris from around it suggest that its superstructure was stone with timber reinforcements, stuccoed and painted to look like freestone masonry: some stones from it were drilled, probably to hold pliable rods to be used in a basket framework for creating round-headed, or even circular, windows from stucco and plaster. Also probably in use at this time was a curious structure interpreted as a fowl-house, and other ancillary buildings.50 The whole complex suggests a substantial hall in which the king could entertain, a private chapel for his devotions, and an associated complex in which farm stock was kept. There is also continued evidence of various craft activities from the rubbish pits and other contexts. Bits of bowl furnaces and iron ores attest smelting, and unfinished tools being worked up by smiths. There are crucible fragments and residues from gold, silver, enamel and copper-alloy working, moulds, and a cast blank apparently waiting to be turned into a strap-end. Much of this came from near the chapel, so there was a focal area for metal crafts there.

Another site with known ownership is North Elmham, centre of a bishop's see until its transfer, first to Thetford and then to Norwich, after the Norman Conquest. The area of what may have been the bishop's palace, in the late ninth and tenth centuries, which overlies mid Saxon buildings and wells, contained a timber structure large enough at eighteen by seven metres to be regarded as a ‘hall’, with other buildings including latrines grouped irregularly around a courtyard. There is no evidence from this site of craft-working.51

Some residential sites with halls have not been investigated on a large enough scale for all their functions to be clear. Waltham, the estate in Hampshire which King Edward exchanged for Portchester, has for instance produced a building perhaps to be identified as a hall of the early eleventh century, but there is no indication of any production activity linked to it. Goltho, however, whose pre-Conquest owners are unknown, still probably had weaving sheds (6, 1). Another Hampshire site of this kind, Netherton, had a complex of timber buildings probably at one time owned by a rich lady named Wynflaed whose will survives. Associated with it is evidence of metal-working in gold, silver and copper alloy that implies regular if intermittent production. Itinerant jewellers might be responsible, but if so it is difficult to see why the residues should all have been concentrated on one part of the site, as though that was a distinct workshop area.52

There is not yet enough evidence from these sites for a clear pattern to emerge, but it does seem likely that they should be seen as production centres, as well as consumption centres where the well-to-do fed off the better cuts of meat—the animal bones at Cheddar indicate that the animals eaten were slaughtered when younger and were therefore more tender than those in Lincoln or Bedford—and to patronise jewellers to make them trinkets. Some of the objects at Cheddar, Netherton and Portchester are of notable quality, though those datable can mostly be attributed to the later ninth or early tenth centuries rather than later. If it is valid to see textile, metal, bone-working and perhaps other crafts being practised at these sites, and if they were also places to which people had to come to pay their taxes if it were the king's palace, or their rent if it were their lord's residence, a buying and selling function could easily have developed. It does not seem to have done so, perhaps because of royal control: as with minting, so with markets, for tenth-century laws stipulated that transactions should be made in ports where they could be witnessed. Archaeology suggests that the royal command was likely to be obeyed.