Nowhere is quite like Fez. One of the oldest and most historic cities in North Africa, Fez was for many years Morocco’s capital and one of the world’s greatest centres of Islamic learning – the ‘Athens of Africa’, as it was reverentially christened, home to possibly the world’s oldest university (established 859) and the largest mosque outside Mecca and Medina. It was also one of the Maghreb’s great trading centres and cross-cultural melting pots, its original Arab and Berber population significantly bolstered by refugees from Andalusia and migrants from Tunisia.

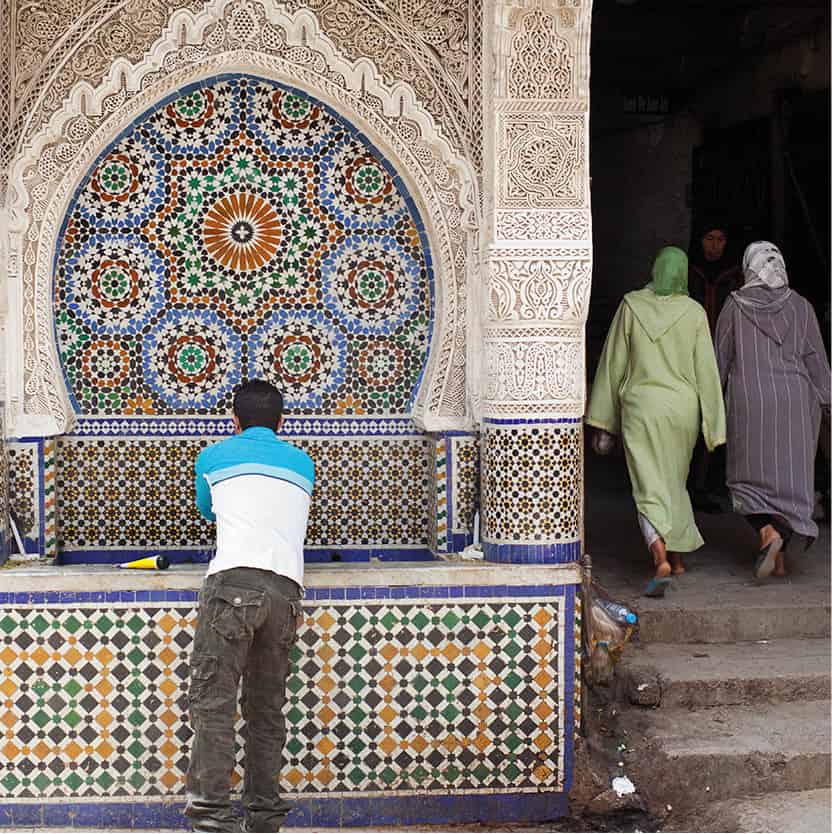

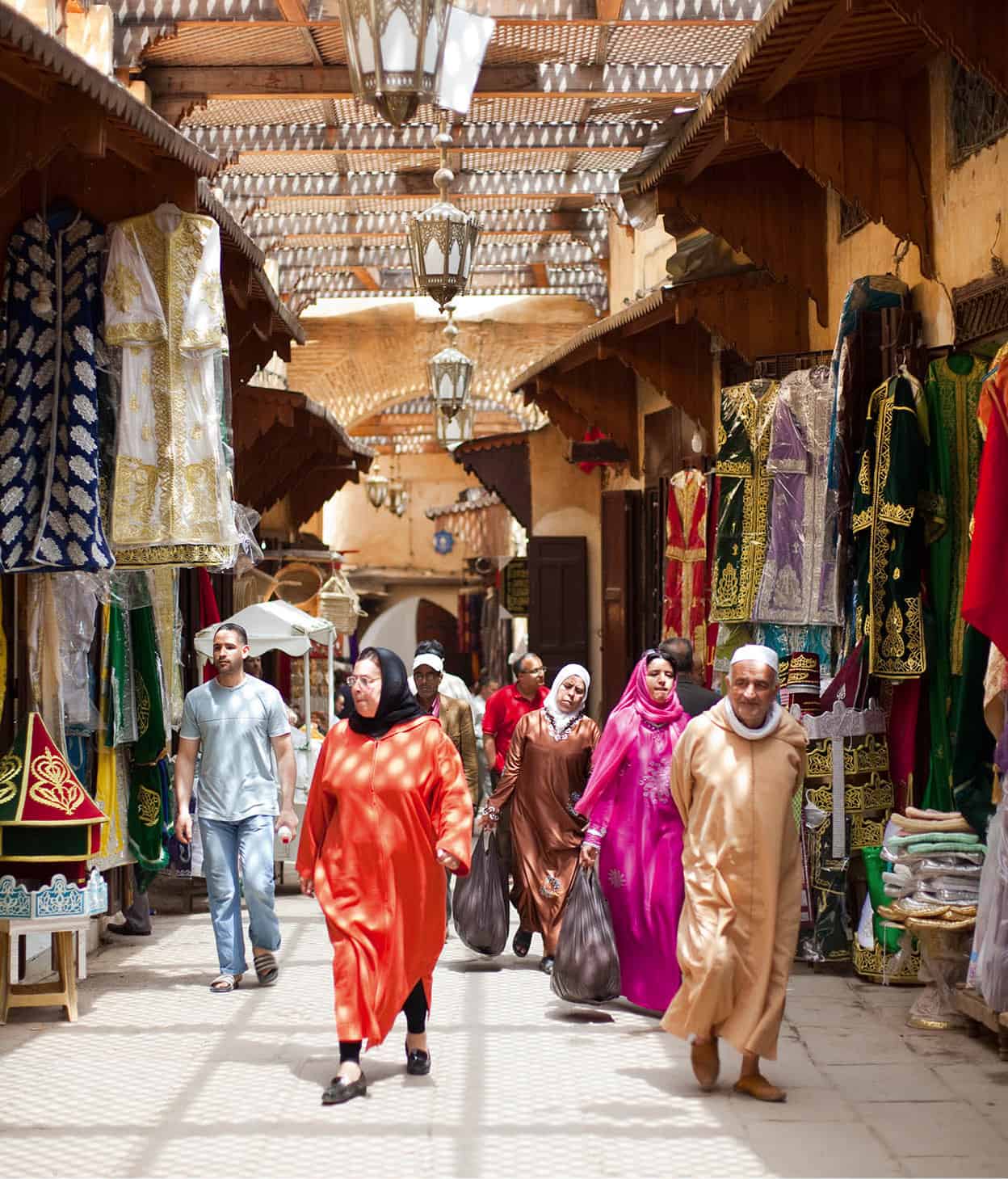

Wrapped up within its imposing circuit of crenellated walls, the old medina city of Fez el Bali remains the world’s most perfectly preserved medieval city, said to be the planet’s largest car-free urban area – with mules still more common than motorbikes, and with tanners, metalworkers, potters, carpenters and shoemakers continuing to practice their crafts as they have done for hundreds of years. Physically the medina remains the most baffling in the country (possibly the world), a vast maze of narrow streets honeycombed with innumerable alleyways, courtyards, dead-ends and blind turnings opening up here and there to reveal a sudden glimpse of a minaret soaring above the rooftops or the splash of colourful tiles decorating a roadside fountain. Foreign money and increasing numbers of tourists have poured into the city in recent years but have done little to change the medina’s essential character, and despite the handicrafts shops and hawkers lining the major streets, the medina remains absorbingly untouched, mysterious and fundamentally secretive.

Fez el Bali, with the Kairaouine Mosque in the centre.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Fez women.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Imperial city

The first French Resident-General, Marshal Lyautey, declared Fez el Bali and Fez el Jdid a historic monument and slapped a preservation order on it, which preserved the city’s remarkable medieval culture but without providing for its future economic health (whose subsequent decline was exacerbated by the construction of the Ville Nouvelle and the transfer of many economic and administrative functions to the new capital of Rabat). For many years, the future of the medina hung in the balance – the once-great palaces crumbled and fell and the medina became tattered and worn. In 1981 Unesco named it a World Heritage Site, and in recent years both money and tourists have come flooding in. Much as in Marrakech, there has been a boom in foreigners buying old riads and restoring them to their former glory. Fez is enjoying a huge surge in popularity, with boutique riad hotels and restaurants opening. But, as the soul of spiritual, intellectual and cultural Morocco for over 1,000 years, it also is more serious and aloof than Marrakech.

In order to attract more tourists to Fez and boost its image as country’s ‘spiritual capital’, local authorities and central government have embarked on an ambitious programme to enrich the city’s cultural offer in the next few years. Projects include a new Institute of Fine Arts (due to be completed in 2019), theatre, a conference centre and another museum, all of which will benefit artists, academics, tourists and citizens alike. There are also plans to build a huge artificial beach with a marina that will accommodate jet skis and small boats around Oued Fez, near the Royal Palace.

An overview of Fez

Fez (also spelt Fes, or Fès) is now served by motorway from Rabat, and even if you are coming from Marrakech it is faster to take the long way around via Casablanca rather than the seemingly more direct road via Beni Mellal and the Middle Atlas (though the latter is more attractive).

Fez itself divides into three main parts: the original medina-city, now known as Fez el Bali; the misleadingly named 13th-century district of Fez el Jdid (New Fez); and the Ville Nouvelle, built by the French in the 19th century. The three areas are quite widely spread out, and it’s the best part of a 30-minute walk from the Ville Nouvelle to Fez el Bali – a pleasant enough stroll via Fez el Jdid, although you might prefer to catch a petit taxi (around 20 to 30dh) between the two, especially if you’ve been hiking around the medina all day. Various buses (recently equipped with Wi-Fi) also connect the two districts, although working out routes can be tricky, and it’s generally a lot less bother to catch a cab.

In high summer, the heat can be stifling. Indeed, Fassis (local residents) who can afford it escape to the North Coast during July and August. Air conditioning is practically essential, and hotels with pools are at a premium.

Fez at night.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The first city

The original medina-city, Fez el Bali, stretches out on both sides of the small Oued Fez river. The area divides into two parts, facing one another across the Oued Fez. The Kairaouine Quarter on the west bank of the river dates from about 825, when over 2,000 Arab families from Kairouan in Tunisia came here as refugees. The Andalous Quarter on the east bank was established a few years earlier, when 8,000 Arab families fled Al-Andalus following a failed rebellion against the Umayyad rulers in Córdoba and settled here, bringing with them the skills and learning that made Fez an outstanding centre of culture and craftsmanship.

As Arab rule in Spain drew to its end, further influxes of refugees from Córdoba, Seville and Granada arrived. They introduced the mosques, stucco, mosaics and other decorative arts, and a variety of trades that are still central to the medina’s economic survival. The strategic division between the two quarters was used by warring factions through the centuries until Youssef Ben Tashfine of the Almoravide dynasty took control in the 11th century. Although Marrakech was his capital, he did great things for Fez, demolishing the wall dividing the two quarters and building a bridge across the river. This helped, but even today you are aware of the distinction between the two.

Mosques were built in each quarter and, seen from above, the quarters appear to form a kind of amphitheatre around the Kairaouine Mosque (Fez’s most important building), the green tiles marking out its total area. To the right of the Kairaouine as you look down on the city, a thin minaret marks the other great religious monument of Fez, the Zaouia of Moulay Idriss II. The Andalous Mosque, a similar focal point, is on the east bank of the river.

Most visitors enter Fez el Bali via the landmark Bab Boujeloud, set back behind a large open square. Approaching from Fez el Jdid, you don’t immediately see Bab Boujeloud, which is hidden behind buildings, although you will see a large gateway away to the left which is easily mistaken for Bab Boujeloud itself, although it leads only into the self-contained Kasbah des Filalas rather than the main medina itself.

In recent years, the old medina received a facelift thanks to the multimillion rehabilitation project aimed at restoring decaying ancient buildings and historical sites. As a result, the famous madrasas Sbaiyine and Sahrij, Mesbahia and Mohammadia, the historical bridges Khrachfiyine and Terrafine as well as the dyers’ souk, the Quaraouiyine library, the Sidi Hrazem shrine and many riads were meticulously restored.

Rooftops of the Kairaouine Mosque.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Kids playing in the mellah.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

A Guide to Guides in Fez el Bali

Finding your way around Fez el Bali is a challenge, and most strangers to the city find it worthwhile to hire a guide. Fix a price before you start, though at the end he (or she) may disarmingly suggest you pay what you think the tour was worth. Don’t get drawn into this. There are fixed rates for official guides (posted in the tourist office) so work on that basis – though you’ll most likely be asked for more. You can arrange an official guide through your hotel or the tourist office on Place Mohammed V. Despite the Tourist Police (Brigade Touristique), ‘faux guides’ can still be a problem, particularly around Boujeloud Gate.

Part of your tour will inevitably include an expensive visit to a carpet emporium or cooperative. If you have no desire to buy and are short of time, try to make this clear at the outset, although you won’t be believed. If you do find yourself being sucked into the sales patter, retreat politely. If you are guideless and taking your chance alone in the medina, remember that any young lad will guide you out (for a few dirhams) should you get lost. Recently, too, the city has placed coloured signposts around the medina directing visitors on five different walks, themed by traditional Fassi culture – these also serve as pointers to the nearest major landmark in the likely event that you become lost.

Batha Museum

Before plunging into the medina proper, it’s worth a visit to the Batha Museum 1 [map] (Wed–Mon 8.30am–4.30pm) in the Dar Batha Palace on Place de l’Istiqlal, just south of the main entrance to the medina at Bab Boujeloud. Inside, rooms open off a central garden, each one dedicated to a particular Moroccan craft and its application in everyday life. The guide (who expects a small tip) will shed light on the purpose of the various articles on display, from the measure for determining the optimum level of alms to the bristle necklace placed around the necks of male calves so that their mothers, painfully pricked when their young came to suckle, would kick them away, forcing them to graze on the herbs that made their meat particularly sweet.

One of the main entrances to the medina is through the Bab Boujeloud 2 [map] to the east of the palace area. Cars are not allowed in the medina, but parking is available around the gates, which are also ringed by simple cafés and restaurants, including the popular Medina Café and Le Kasbah. Taxis can be picked up from Place Baghadi just by the gate, while all long-distance buses (apart from CTM services) leave from the main bus station nearby, just outside Bab Mabrouk.

Bab Boujeloud.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The Boujeloud Gate, built in 1913, is one of Fez’s more recent babs (gates) but is traditionally tiled and decorated: blue and gold outside, reputedly to represent the city of Fez, and green and gold inside to represent Islam. Just inside the gate, the square splits into the two main streets: Talaa Kebira (Grand Talaa), the upper one on the left (inside the gate make a left turn followed immediately by a right), and the less interesting and quieter Talaa Sghira (Small Talaa), running parallel straight ahead.

Initial impressions of the medina may be chaotic, but in fact its various areas followed a carefully planned structure. Each quarter has its own mosque, foundouk, Qur’anic school, water fountain, hammam and bakery, where everyone in the quarter brings their own dough to be baked in the central ovens (marks of identification help avoid confusion). Daily prayers are attended in the mosque of the quarter, the Grand Mosques being used on Fridays, when people flock from all areas for this special prayer day.

Just off the square, on the upper reaches of Talaa Kebira, is one of the most famous sights in Fez, the much-photographed Medersa Bou Inania 3 [map] (daily 8.30am–5.30pm), an exuberant example of Merinid architecture. Medersas, or Islamic schools, formerly played an important role in the cultural life of Morocco, supported by endowments from sultans and revenues from local inhabitants, and some of the most beautiful are in Fez. Medersas served as lodging houses for students who were strangers to the town, the idea being that segregation from the wider community would help them concentrate on their religious studies. For convenience, they were built close to the mosque where the students went for their lessons. Similar in structure to mosques and private houses, medersas are centred on a courtyard and elaborately decorated with zellige, lacy stucco and cedar-wood carvings. Students often spent more than 10 years at university, so places to live were at a premium. Recently, King Mohammed VI has instructed that five of the historical madrasas should be restored to their former glory.

Medersa Bou Inania.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Date stall in the medina.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The Future of the Medina

Fez is one of the most culturally important – and most fragile – cities in the world. But there is hope for its future.

Fez embodies all the problems facing medinas in the modern world. For centuries it was the political and cultural capital of Morocco and is still seen as the centre of intellectual endeavour. But its 1,200-year-old medina relies upon the interdependence of industries and social structures for its survival. Contrary to some visitors’ impressions, it doesn’t exist as a museum, and its souks do not stock merely tourist trinkets; the Fassis rely on their industries, and their leather goods, silverware and cedar work are sold throughout the country to Moroccans. Over 200,000 people live and work in the medina, and it’s clear to anyone wandering through the packed souks that tourists are irrelevant to most of the inhabitants.

Old methods are still used by the tradesmen and artisans. There isn’t room in the city to introduce new technology, open new factories and streamline production, even if they were wanted. So far only some of the potteries have been moved out of the centre to hillsides close by, where new technology could be introduced. But such progress is beset by problems: break a part of the vast structure of the medina and it all might crumble.

Overcrowding is the main cause of Fez’s ills. Over the past 50 years people have been moving into the town from the countryside to find work, putting Fez under severe strain. Certain public infrastructures, such as water supplies and 13th-century sewage systems, are at breaking point. There is no new housing available, and shanty towns have spawned on the nearby hillsides. The different quarters of the city are gradually losing their individual functions.

Preserving Morocco’s heritage

But there is also cause for optimism. In 1980 Unesco launched an appeal and introduced an ambitious programme of restoration. In 2001 a development plan for the medina was adopted, which safeguards houses close to collapse and promotes regional tourism. Now working in partnership with the World Bank and the Italian government, Unesco has set up Ader-Fez (Agence pour la Dédensification et la Réhabilitation de la Médina de Fès). Their task is enormous and would seem impossible, but work is under way. The objective is to keep the medina as a working structure – reinforcing its foundations both physically and administratively. The project has extended to include Fez el Jdid as well as Fez el Bali. One of the elements that contributed to Fez being declared a site of Outstanding Universal Value is the ‘survival of architectural know-how’ – the fact that the medieval craft traditions of the city remain a living, essential part of trade and commerce in the city – and the continued authenticity of the city. Unesco and all those involved in the restoration and preservation of the medina acknowledge that it is the survival of these trades that contributes to the survival of the medina itself, through the restoration of its palaces and houses.

In recent years, there has been a considerable surge in tourism, with expats and wealthy locals buying and renovating decaying riads into guesthouses and boutique hotels, and kick-starting the general gentrification of the medina as a whole. Increasing numbers of expats also now choose to live in the medina, making vital contributions towards rescuing some of the city’s most historic buildings.

Local lore

According to local sources – almost certainly unreliable in view of the Moroccans’ love of cautionary tales – the origins of the Medersa Bou Inania are rooted in a rich subsoil of sex and scandal. The Sultan Abou Inan was renowned for his extravagant lifestyle and extensive harem, but there came a point in his dissolute life when, deeply in love with a concubine, he vowed to atone. He made his lover his wife and, as a public display of his new-found piety, commissioned the Medersa Bou Inania to be built on the site of public latrines inside Boujeloud Gate. But unfortunately the object of his love was a former prostitute-dancer, and his viziers – though impressed by the new medersa – were outraged that the Sultan should honour a whore in this way. The clever Sultan took them to the newly completed building. ‘Did you not use to piss where now you pray?’ he asked, inviting them to see the corollary. From then on the Sultan’s new wife was considered a pillar of respectability.

Selling flower-and herb- infused waters.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Abou Inan wanted his medersa to rival the Kairaouine Mosque, and it did indeed become one of the most important religious buildings in the city. He failed in his aim to have the call to prayer transferred here from the Kairaouine, but it was granted the status of Grand Mosque, unheard of for a medersa, and midday prayers are still heard here (during which the building is closed), making it is one of Morocco’s few buildings in religious use that can be entered by non-Muslims.

The building follows the usual layout, but the quality and intricacy of the decoration are outstanding. The courtyard facade is decorated with carved stucco, above which majestic cedar-wood arches support a frieze and corbelled porch. The examples of cedar-wood carving, stucco work, Kufic script writing and zellige work are outstanding.

Opposite the Bou Inania there once stood a remarkable water clock, with thirteen wooden blocks balancing 13 brass bowls (only seven of the original bowls remain) protruding beneath 13 windows. Sultan Abou Inan erected it opposite the medersa to ring out the hour of prayer, hoping its originality would bring further fame to his beloved religious school. Unfortunately, its 14th-century mechanics have defeated modern horologists and the clock has been silent for over five centuries. According to legend, a curse was put on the clock when a passing Jewess was so alarmed by its chime that she miscarried her child.

In 1990, following the discovery of documents detailing the working of the clock, a programme of restoration was begun. However, the work is proving more complex than expected and the clock has yet to be repaired. Near the water clock is the Café Clock (http://fez.cafeclock.com), a wonderful place for a drink or lunch.

Talaa Kebira

Fez el Bali’s main thoroughfare, Talaa Kebira, bisects the entire Kairaouine Quarter, running from just inside the Bab Boujeloud to the Kairaouine Mosque and on to the Zaouia of Moulay Idriss II (for more information, click here). Many of the medina’s most interesting sights lie on or just of the road.

Water, Water Everywhere

Islam blossomed in dusty, dry lands where trees, flowers and water were (and are) especially treasured. Considerable thought was therefore expended in solving problems of irrigation, and in cities water was introduced wherever possible, in splashing fountains and pools, both to provide a convenient supply of drinking water, and also in order to help to cool the air within crowded medinas. The fact that Fez has so many fountains is thanks to the vision of the Almoravid Sultan Youssef Ben Tashfine, who rerouted the Oued Fez river and created an elaborate network of channels in order to carry water throughout the city. By the late 11th century every mosque, medersa and fondouk, as well as most of the richer households, had water, and there were numerous street fountains and public baths. The system included a successful method of flushing the drains.

The sound and sight of Fez’s many drinking fountains refresh the senses, though many have now run dry, and it is best not to drink from those that still have water in them. The fountains are notable for elaborate zellige settings, exemplified by the magnificent Nejjarine Fountain. Wear, tear and pollution have dulled the brilliance of the stonework, and in some cases destroyed the pipes feeding the fountains, although restoration work (www.fez-riads.com/restoration) is slowly returning them to their former glory.

Facade of the Nejjarine Fountain, one of the finest in Fez.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

From Bab Boujeloud, Talaa Kebira runs steadily downhill for most of its length down into the valley of the Oued Fez and the Kairaouine Mosque. A few hundred metres past the Medersa Bou Inania, you pass a cluster of fondouks – just a few of the more than 200 fondouks that once dotted Fez el Bali. Now mainly used as warehouses, these were created at about the same time as the medersa as lodgings for traders and their mules: large two-storey buildings with rooms arranged on galleries around spacious centre courtyards.

Notable examples include the Bousl Hame at No. 49 Talaa Kebira (on the left), now occupied by an interesting drum workshop, and, about 50 metres/yds beyond, the Qaât Smen (signed on the right), home to a small butter and honey market (announced by the strong smell of smen – an aged and expensive butter used in the best couscous). Shortly past here (also on the right) is the ramshackle Fondouk Tazi, with a small cluster of pottery stalls and workshops, and, a few metres beyond (on the left) the largely derelict and memorably smelly Fondouk Lbbata, piled high with sheepskins being stripped from carcasses prior to curing and tanning.

Tip

As Talaa Kebira starts to go downhill a few hundred metres past Medersa Bou Inania, look out on the right for the one-time home (marked by a plaque) of Ibn Khaldoun, a famous 14th-century historian from Tunis who wrote a seminal history of the Arabs.

Past the fondouks, Talaa Kebira begins to descend more steeply, passing beneath a small archway beyond which the fine green and white minaret of the late 18th-century Chrabliyine Mosque comes suddenly into view, framed by the bulging upper storeys of the buildings.

The road now changes its name to Rue es Chrabliyine (Slipper-Makers’ Street), lined with dozens of shops selling babouches, the traditional soft leather shoes still worn by many Moroccans. With their backs turned down so that they are easy to slip on and off on entering a home or mosque, babouches come in a wide range of colours, though, for men, yellow is the popular choice for everyday use and white for Fridays and other holy days. Women’s babouches, in velvet, silk and nylon, as well as leather, come in a huge range of colours, often bejewelled or embroidered with gold thread.

Fact

Around the medina you may see children contributing to the family finances by making the braid used to trim kaftans. They secure the ends of the thread to the corners of buildings and then painstakingly entwine the different strands.

Past the babouche shops, the street descends steeply again, narrowing and disappearing beneath a latticed wooden roof as it enters the Souk el Attarine 4 [map]. This area is the commercial centre of the medina, honeycombed with the densest and most disorienting tangle of alleyways you’ll find anywhere in Morocco and promising instant confusion the moment you step off the main drag. Souk el Attarine itself is the medina’s traditional perfume and spice-sellers’ souk, selling old-fashioned Arabian perfumes such as musk and amber, although many of the tightly packed shops are now filled with more workaday household items.

Continue through the souk, looking out for the Dar Saada restaurant (http://restaurantsaada.com) on your left. Directly opposite this, a small alleyway leads straight into the picture-perfect little Souk el Henna, a tiny little square shaded by a pair of venerable plane trees. Huge piles of local pottery lie stacked up along one side of the square, while opposite are a line of traditional herbalists with baskets of green henna leaves, camomile, rose buds, antimony and olive soap – not to mention more outlandish items such as powdered chameleons to treat warts and charms to ward off the evil eye.

Traditional Cosmetics

Moroccan women take great pride in their appearance, often using cosmetics until well into old age. Though they may let their figures go, their faces remain unlined and their hair stays beautifully strong and shiny.

Nowadays, all Moroccan markets have numerous stalls selling international-brand toiletries and cosmetics, but tried-and-tested traditional beauty products, such as antimony for the eyes, crushed rose buds and cloves to scent the hair, olive-oil soap for the skin and red salve for the cheeks and lips remain popular. Henna is used by almost everyone. As well as adding lustre to hair, it is used to decorate women’s hands and feet on special occasions such as festivals and weddings, when professional henna painters are hired to create the most intricate designs. The henna leaves are boiled to produce a green paste that is piped onto the hands in elaborate designs and fixed with lemon juice. When dry the crusty paste is removed, leaving lace-like orange patterns. As well as being decorative, the henna is said to protect its wearer from the evil eye.

In recent years an interest in Moroccan beauty products has spread through Europe. In particular, argan oil (for more information, click here) is gaining a reputation for its healing properties, especially for erasing skin blemishes.

Exit the back of the Souk el Henna, then turn left and right to reach the intimate Place el Nejjarine 5 [map]. Dominating the corner of the square is the wonderful Fondouk el Nejjarine (daily 10am–5pm), dating from the late 17th century and heavy with the scent of worked cedar and thuya wood, which has been beautifully restored and now serves as a museum devoted to woodworking techniques and tools. Here craftsmen crouch over finely carved tables, bed heads, chairs and every kind of wooden creation. The view from the rooftop café is amazing.

The Nejjarine Fountain, the focal point of the square, is an outstanding example of zellige decoration and stands almost like a shrine to water. On your right, a large covered workshop is devoted to the making of extravagantly chintzy snow-white palanquins and thrones used on a variety of festive occasions – to carry boys undergoing circumcision, or to carry a bride or bridegroom to their wedding.

In a Fez souk.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Exit Place Nejjarine the way you came in and continue directly ahead to enter the horm, the sacred area around the Zaouia (shrine) of Moulay Idriss II 6 [map], the effective founder of Fez. The boundaries of the horm are marked by chest-high wooden bars set across all entrances to the area; until the French Protectorate this barred not only mules and donkeys but also Jews and Christians. It also marked a refuge for Muslims, who could not be arrested in this area.

Babouches for sale.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The zaouia itself is announced by bright stalls selling candles, incense, padded baskets for gifts, and nougat, dates and nuts, the usual signs in Morocco that one is approaching a shrine – along with beggars accosting pilgrims on their way to devotions. The tomb was built by the Idrissids in the 9th century but was allowed to fall into decay until it was rebuilt in the 13th century by the Merinids. The Wattasids rediscovered the tomb and from this period it became the revered shrine it is now. Non-Muslims are not allowed inside, although you can look through for a glimpse of the richly tiled and carpeted interior, complete with a trio of chandeliers and a pair of grandfather clocks. In September the shrine is the focus of a huge moussem.

Passing the time with a board game.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Continue past the shrine to reach the Kissaria 7 [map], a covered market arranged around a tight (and supremely disorienting) grid of narrow alleyways and selling the luxury items traditionally sold in the vicinity of the Kairaouine Mosque – embroidery, silks and brocades, as well as imported goods.

Medersa el Attarine

Find your way back to Souk el Attarine and then continue east to reach a major junction, with the vast Kairaouine Mosque stretching away to your right. Immediately in front of you is the Medersa el Attarine 8 [map], one of several medersas around the Kairaouine Mosque. The medersa was built by Sultan Abou Said between 1322 and 1325 and is similar in design to the later Bou Inania (for more information, click here); no doubt many of the same master craftsmen worked on its interior. The medersa is no longer in religious use and can be visited (daily 8.30am–5.30pm), offering glimpses into the neighbouring Kairaouine Mosque from its rooftop.

Medersa el Attarine.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The Great Mosque

All roads in the medina lead to the vast Kairaouine Mosque 9 [map] (closed to non-Muslims), which serves as the Great Mosque of Fez el Bali. Rivalled in size only by the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, it covers 16,000 sq metres (4 acres) and can accommodate more than 20,000 people. It was founded in 859 by Lalla Fatima el Fihrya, a pious woman from Kairouan, Tunisia, one in a wave of immigrants from Kairouan. The mosque, then merely a small prayer hall, was built in memory of her father.

Each of Morocco’s sultans added to the mosque and changed it. The Merinids’ alterations in the 13th century cast it in its present mould. Green tiled roofs cover 16 naves and the tiled courtyards have two end pavilions, added by the Saadians, and a beautiful 16th-century fountain reminiscent of the Court of Lions of the Alhambra in Granada. Despite its size, the mosque has been so thoroughly buried by surrounding buildings that it is surprisingly difficult to get any real sense of its extent or shape, and although tantalizing glimpses of the interior can be had through the various entrances when opened during prayer time –overall the mosque remains (for non-Muslims at least) a frustratingly mysterious presence at the heart of the medina. The best views of the complex are to be had from the rooftops of surrounding buildings – the lofty Borj Kairaouine, opposite the Medersa el Attarine, offers possibly the best.

The sanctuary interior is austere, with horseshoe arches over some 270 columns. It was most probably the first university in the world, and was considered a great seat of learning; its reputation attracted over 8,000 students in the 14th century, and it even boasted a future pope, Sylvester II (pope 999–1003), among its students, as well as Ibn Khaldoun, the great Arab polymath, and Averroes (Ibn Rushd). The university remains one of the most important centres of spiritual and intellectual Islam in the world.

The recently restored Kairaouine Library, on the far side of the mosque, is also thought to have been built in the 9th century. It contains one of the largest collections of Islamic literature in the world.

Walk anti-clockwise around the mosque to reach the pretty little tree-shaded Place Seffarine ) [map]. The square is mainly occupied by piles of huge cauldrons are stacked in every available space and the workshops of various metalworkers, whose arrhythmic cacophony of hammering can be heard long before you reach the square itself. The same skills were used on the redecoration of the great doors to the Royal Palace, visible across Place des Alaouites as you approach Fez el Jdid from the Ville Nouvelle (for more information, click here). If you can gain access to the Medersa Seffarine close by, climb up to its roof for a view of the overall scene.

Metalwork in the Place Seffarine.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Take the north exit from Place Seffarine and follow the road around for a few minutes to reach the recently restored Chouaras Tanneries ! [map] (Sat–Thu 9am–6pm; best visited in the morning to see the tanners at work), on the River Fez – hustlers anxious to show you the tanneries (and extract a healthy tip in return) will most likely descend on you en masse as soon as you approach the area. These are the largest of the three tanneries in Fez – and announced by the pervasive and stomach-churching stench of fresh animal hides steeped in urine. Guides offer visitors sprigs of mint to block out the stench.

The area has hardly changed since medieval times. Hides are treated in a honeycomb of small open-air stone vats, each bright with a differently coloured dye and marvellously photogenic when the light falls on them in the mornings, like some enormous painter’s palette, while surrounding roofs are hung with drying skins. The tanneries are run as a cooperative, with each foreman responsible for his own workforce and tools. Jobs, which are strenuous and smelly but well paid, are practically hereditary. Visitors are trooped through the walkways and helped up small uneven steps to vantage points for photographs.

Dyeing leather in the Chouaras Tanneries.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The Andalous quarter

Back at Place Seffarine, take the southern exit (opposite the road to the tanneries) and cross the bridge over the Oued Fez – a remarkable, modest little river, given its significance in the city’s history. Beyond here stretches the El Andalous Quarter @ [map], named after the Arab refugees from Spain who settled here in 818. This is the second of Fez el Bali’s major quarters, although it sees few tourists, and has relatively few sights and a determinedly workaday atmosphere compared with the touristy Kairaouine district.

The quarter’s major landmark is the magnificent Andalous Mosque £ [map], founded shortly after the Kairaouine Mosque in the 9th century and embellished by the Almohads at the beginning of the 13th century (to reach the mosque, turn right immediately inside the Bab Recif gateway and follow the road as it winds uphill – overhead signs will point you in the right direction if you get lost). The great north gate is particularly impressive, towering over the surrounding streets and decorated with zellige tile work and a magnificent cedar porch.

A couple of medersas stand in the lee of the mosque. Follow the alleyways around the right-hand side of the mosque to reach the beautifully restored Medersa es Sahrija, an early 14th-century structure with an ablutions pool in the centre of the courtyard. Its zellige decorations are some of the oldest in the country and it has an impressive ancient wood minbar (pulpit).

El Andalous Quarter.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Walking up the hill brings you out of the medina at the Bab Ftouh gate, from where buses and taxis leave for the Ville Nouvelle via the ring road.

Across from Ftouh Gate is the main cemetery, which on Fridays becomes as busy as a railway station, as families come to sprinkle water on the graves, to leave sprigs of olive and to picnic beside the tombs of their dead loved ones. Non-Muslims are not welcome.

Moroccan pottery.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Round the city walls

Retrace your steps back down through the Andalous Quarter, across the river and back to Souk el Attarine, then take the road north (opposite the back of the Souk el Henna) to Bab Guissa – once again, helpful overhead signs point you in the right direction if you become lost. This area of the medina is determinedly local, with hardly any tourists in sight, offering an interesting alternative view of old Fez in the raw, away from the handicraft shops and tourist emporia of Talaa Kebira.

En route to Bab Guissa, a turning on the right leads past the elaborate stucco entrance of the Zaouia of Sidi Ahmed Tijani. The inspiration behind a major Sufi sect of North and West Africa. Ahmed Tijani (1737–81) began his journey to sainthood at the age of seven, by which time he had memorised the Qur’an.

Past here, the historic Sofitel Palais Jamai Hotel offers a good place for lunch or tea on the terrace by its pool. The hotel was built at the end of the 19th century as a palace by the Ulad Jamai brothers, viziers of Sultan Moulay Hassan. The brothers eventually fell foul of the political machinations of the day, and when Moulay Abd el Aziz succeeded to the throne in 1894 they were sent in fetters to Tetouan. Walter Harris, correspondent of the London Times, related their fate in his book Morocco That Was: ‘In the course of time – and how long those ten years must have been – Haj Amaati died. The Governor of Tetouan was afraid to bury the body, lest he should be accused of having allowed his prisoner to escape. He wrote to Court for instructions. It was summer, and even the dungeon was hot. The answer did not come for eleven days, and all that time Si Mohammed Soreir remained chained to his brother’s corpse.’

Continuing north you exit the medina at the Bab Guissa and the ring-road around the medina city walls, the so-called Tour de Fez. High on a steep hillside opposite Bab Guissa are the remains of the Merinid Tombs $ [map], the mausoleums of the last Merinid sultans. Described in the chronicles as beautiful white marble with vividly coloured epitaphs, the tombs are now a no more than a cluster of crumbling ruins. The views are sensational, however, offering a bird’s-eye panorama of the medina and the chance to appreciate the scale, complexity and sheer mind-boggling density of the medina from a privileged vantage point.

Behind the Merinid Tombs is the five-star Hôtel Les Mérinides, an ugly but brilliantly positioned hotel. The Borj Nord, a 16th-century military fortress dating from the Saadian era, is just below the hotel and is now a museum, the recently restored Arms Museum % [map] (Musée des Armes; Tue–Sun 8.30am–5pm, until 6.30pm in summer), which houses a collection of weapons, including the huge cannon used during the battle of the Three Kings.

Looking across the medina from the Arms Museum you can make out the Borj Sud, standing sentinel on a hillside on the far side of the medina amid olive trees and gravestones. Many of the hillsides surrounding Fez are dotted with white tombstones, as there is no room for graves inside the city. On Friday, the Muslim holy day, it is customary for families to visit the graves of loved ones.

Descending from the Arms Museum, the Tour de Fez brings you back to Bab Mabrouk and the large open square in front of Bab Boujeloud, where you began you tour of the medina.

Fez el Jdid

East of Fez el Bali stretches the confusingly named quarter of Fez el Jdid (New Fez), built by the Merinids in the 13th century and sprawling between the medina and Ville Nouvelle, with the old Jewish mellah on its southeastern side. Fez el Jdid was laid out by the Merinids during the 13th century to incorporate an impressive Royal Palace and gardens, and as the administrative centre of Fez; its regal grandeur and wide-open spaces still contrast strikingly with the nearby medina. The quarter’s significance diminished greatly when the French moved the centre of government to Rabat.

West of Bab Boujeloud stretches the Avenue des Français, which borders the peaceful and attractive Jardins du Boujeloud (also known as the Jnane Sbil; daily 8am–6pm; free) on one side. The walls between Fez el Bali and Fez el Jdid were joined at the end of the 19th century and some of the buildings around this area date from that time.

The western end of Avenue des Français leads you into the small square of the Petit Méchouar at the back of the Royal Palace, ringed by high walls and a perplexing number of gateways. Heading due south from here leads you into the Grande Rue de Fez Jdid, a lively souk street crammed with clothes and textile shops – usually gridlocked with local shoppers from late afternoon onwards – from which you emerge at the impressive Bab Semarine at the western end of the old Jewish mellah.

World Sacred Music Festival

Fez, the cultural and religious capital of Morocco, is a fitting venue for the annual Fez Festival of World Sacred Music (www.fesfestival.com), held in late May/early June. The festival was established by the Sufi scholar Dr Faouzi Skali in 1994 and is organised by Fez Saiss, the association set up to help save the city’s historical and cultural heritage. It is one of the most popular and successful global music festivals in the world, attracting world-class spiritual singers of many nationalities and faiths, from Turkish Whirling Dervishes to gospel choirs from Harlem. It is also the place to come if you want to learn more about Sufism, as part of the festival, known as ‘Sufi Nights’, programmes Sufi music from all over Morocco (and beyond), including the trance music of the Aissawa and Hamaacha brotherhoods, two famous sects based in the Fez region.

Boujeloud Gate is the main venue for the larger concerts in the festival, but numerous palaces host more intimate gatherings and fringe events, resounding to wonderful music until well into the early hours. The festival is not just about music, but also about the exchange of ideas. In the mornings, exhibitions and conferences encourage people of different faiths to meet and debate spiritual issues. It is essential to book ahead for both tickets and accommodation during the festival.

Jewish Fez

The mellah – the first Jewish quarter in Morocco – was originally sited by the Bab Guissa gate. When Fez el Jdid was built, the Jews were ordered to move to their new quarter near the Sultan’s palace. Many Jews with interests in the medina preferred to become Muslims and thus stay in Fez el Bali. Those who did move were promised protection in consideration of supplementary taxes.

The name mellah, which means ‘salt’ in Arabic, alludes to the job of draining and salting the heads of decapitated rebels before they were impaled on the gates of the town, a task traditionally done by Jews. Morocco’s Jews held an ambiguous position prior to the protectorates; although they were ostensibly under the Sultan’s protection, their freedom was limited. No Jew was allowed to wear shoes or ride outside the mellah, for instance, and further restrictions were placed on their travel elsewhere.

Very few Jewish families are left. What remains are their tall, very un-Arabian buildings with distinctive wooden balconies which line the lively Rue des Mérinides, the heart of the district. Just off this road lies the Ibn Danan Synagogue ^ [map] (Sat–Thu, no set hours, a guardian will let you in; donations), which dates from the 17th century and is a reminder of the mixed cultural heritage of Morocco. After falling into disrepair, the synagogue was restored in collaboration with the World Monuments Funds and Morocco’s Ministry of Culture and reopened in 1999.

The nearby Jewish Cemetery (Cimetière Israélite de Fès) is one of the oldest in Morocco, with rows of tightly packed, pristine white gravestones laid out on the slope of the hill stretching down towards the river. The adjacent Habarim Synagogue (daily 7am–7pm; donations) contains the remains of several eminent rabbis, as well as a woman who allegedly refused to convert to Islam and marry the Sultan and was killed as a result.

The west end of Rue des Mérinides emerges into the spacious Place des Alaouites. Dominating the square is the flamboyant Royal Palace & [map] (Dar el Makhzen; closed to the public), originally built by the Merenids but constantly reworked ever since, and most of what you can see today is largely modern. The entrance to the palace bounding Place des Alaouites is undoubtedly impressive, in a slightly Hollywood sort of way, with huge brass doors surrounded by multi-coloured bands of plasterwork, zellige and calligraphy. The grounds, said to cover 40 hectares (100 acres), are enclosed by high walls.

West of Fez el Jdid stretches the Ville Nouvelle, built by the French after World War I on a grid system that is simplicity itself to navigate after the medina. Fez’s Ville Nouvelle is less interesting than others in the country, lacking the Maurequse touches of Casablanca and Rabat, or the sheer glamour of Marrakech, although there’s a decent if uninspiring selection of hotels and restaurants here if you prefer not to stay in Fez el Bali. The Ville Nouvelle is also usually livelier than the medina in the evenings, as this is where most Fassis choose to spend their time (as in all cities in Morocco, the medina is considered a backward and dull part of the city). The best cafés are found along Avenue Mohammed V, particularly on the crossroads with Avenue Mohammed es Slaoui, where every corner is occupied by a busy café terrace.

Beyond the city

Exit routes west of the Ville Nouvelle head through fertile landscapes to Sidi Kacem or Meknes (for more information, click here). A few kilometres in the other direction are the hot springs and cool sources of Sidi Harazem, where the ubiquitous mineral water is bottled. Site of the shrine of Sidi Harazem, a Sufi mystic, this is a popular pilgrimage site, and can get very crowded at weekends. Unfortunately much of what was once an attractive spot has been concreted over, making it a disappointing escape from the harsh summer heat in Fez.

In October, it is well worth paying a visit to the small town of Tissa, a 48km- (30-mile) drive north-east from Fez on the N8, for its famous Tissa Horse Festival, during which colourfully dressed riders on pure-bred Arab and barb stallions demonstrate their extraordinary showmanship. The show is accompanied by traditional music, dances and food – all washed down by copious amounts of fresh mint tea.

Much further afield, but more rewarding, is the N8, the main route south of Fez to Marrakech. This promises a long but glorious journey through the Middle Atlas Mountains via the delightful Immouzzer du Kandar or the pretty little town of Sefrou, where Moulay Idriss lived whilst building Fez, and on to the cedar forests of Azrou and Ifrane.

One of Fez’s old fondouks.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications