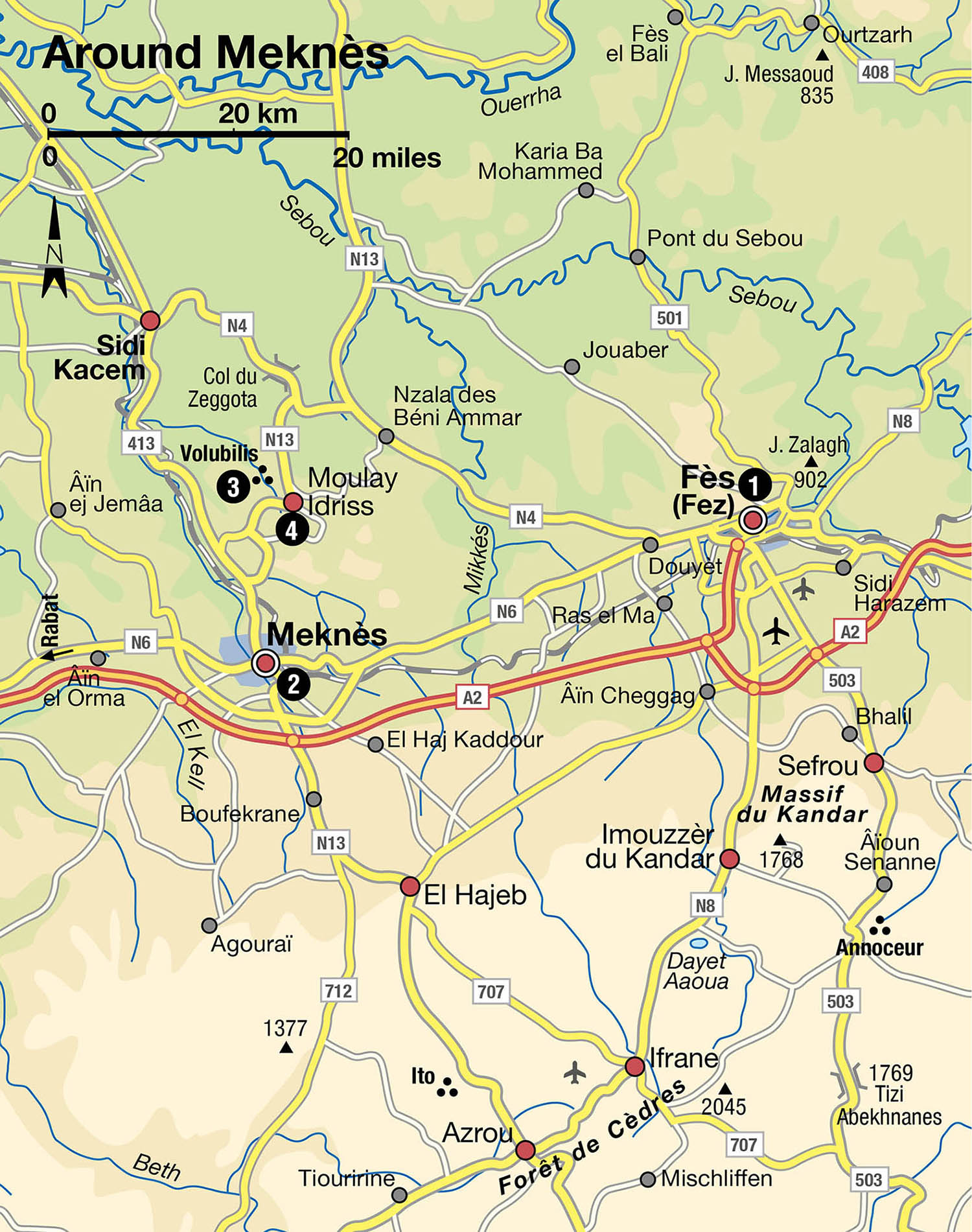

The smallest of Morocco’s four great imperial cities (and the seventh-largest city in the country), Meknes is rather eclipsed both by Fez and Marrakech, but it does see its fair share of foreign visitors and is well worth visiting as a destination in its own right. Its proximity to Fez 1 [map] (for more information, click here) means that it is often treated as a day’s excursion from there rather than as a base in its own right, even though it has several further places of interest on its own doorstep, including the fascinating remains of the Roman city of Volubilis and the pilgrimage town of Moulay Idriss, where the tomb of Idriss I, founder of the Idrissid dynasty, is located.

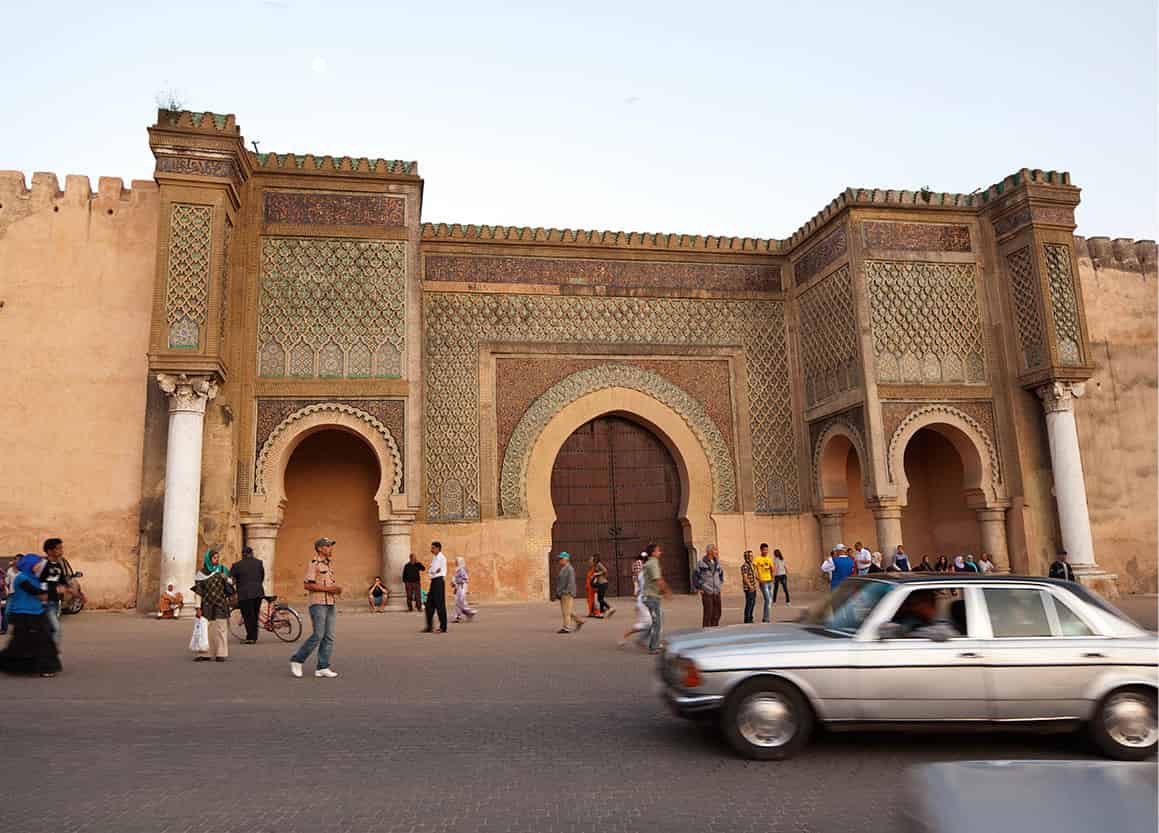

One of Meknes’s gates.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Meknes 2 [map] nestles in attractive countryside peppered with shrines and springs and is renowned for the quality of its olives, as well as lying at the heart of the country’s premier wine-producing region – if you drink a glass of Moroccan red or white, chances are it came from somewhere near here.

Fresh bread is bought daily.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Visiting Meknes

Many people come to Meknes as a day-trip from Fez, sometimes combined with a trip to Volubilis, although this makes from rather a rushed visit and really allow you to do justice to either place. Staying a night or two in Meknes makes for more leisurely and rewarding experience, as well as giving you time to take in the holy town of Moulay Idriss en route.

Father and son at the mosque, Meknes.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Meknes can be reached directly from Fez along the N6, while the short drive to Volubilis from Meknes is very straightforward, heading north on the 413, with Moulay Idriss first (about 25km/16 miles, from Meknes) and Volubilis less than a mile further on. The road between Volubilis and Meknes runs through fertile hills planted with vines and dotted with the white domed tombs of marabouts.

Moulay Ismail

Meknes was the imperial capital of Moulay Ismail, an effective but ruthless sultan who ruled for 55 years (1672–1727) over a more or less united Morocco. During that period Morocco became a significant power in the Mediterranean world – the sultan considered Louis XIV, the Sun King, his contemporary in France, a close friend.

Fact

Meknes has been called the ‘Versailles of Morocco’, and there is evidence that Ismail saw himself as a Moroccan Louis XIV. Ismail recommended the Muslim faith to the French monarch and offered himself as husband to one of Louis’s daughters. Louis politely declined the request, sending the sultan a clock instead.

Moulay Ismail was also renowned for his ruthless tyranny, however. As a celebratory gesture to mark the beginning of his long rule in the mid-17th century he displayed 700 heads on the walls of Fez, impressing his new subjects with a sense of their own vulnerability and setting the tone for the long reign of terror which followed.

Tip

Non-Muslims are forbidden from entering the shrine of Moulay Idriss. The horm (sanctuary area) is clearly delineated by a low wooden bar designed to repel Christians and beasts of burden.

The British diplomat John Windus, who visited Ismail’s palace in 1725 and recorded his impressions in A Journey to Mequinez, observed how ‘about eight or nine [in the morning] his trembling court assemble, which consists of his great officers, and alcaydes, blacks, whites, tawnies and his favourite Jews, all barefooted; and there is bowing and whispering to this and the other eunuch, to know if the Emperor has been abroad (for if he keeps within doors there is no seeing him unless sent for), if he is in a good humour, which is well known by his very looks and motions and sometimes by the colour of the habit he wears, yellow being observed to be his killing colour; from all of which they calculate whether they may hope to live twenty-four hours longer’.

Before Moulay Ismail took control, Meknes was a relatively minor city in the grand scheme of Morocco – always in the shadow of Fez, despite the fact that it was well placed between the Middle and High Atlas mountains and the coast and the interior. Founded in the 10th century by a Berber tribe known as Meknassass, it passed through the hands of all the major dynasties, from the 11th-century Almoravids and the 12th-century Almohads to the Merinids, who built a medersas here, and the Saadians. It was customary for the viziers of the Fez-based Merinid sultans to keep second residences in Meknes, but beyond that, it was considered of no great importance.

Bab Mansour.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Before becoming sultan and moving the court from Fez to Meknes, from where he ruled with an iron grip for 55 years, Moulay Ismail had been the governor of Meknes on behalf of his father, the Alaouite Sultan er Rashid, whom he succeeded in 1672. Both as governor and sultan, Ismail’s excesses were notorious. Reports vary wildly, but some say that he had a harem of 500 wives and concubines, and of the hundreds of children he fathered he had the girls strangled at birth and was not averse to slicing off the limbs of sons who displeased him. To enforce his rule as sultan, he formed an army of 30,000 Sudanese soldiers – the feared ‘Black Guard’ – who roamed the country, keeping the tribes in check.

Grand designs

Meknes’s location, surrounded by fertile land and well connected to local trade routes, made it a good choice for a new imperial capital, while Moulay Ismail immediately set about defending the city itself by building a complex defensive system comprising vast fortifications – including some 25km (15 miles) of walls – a granary and reservoir. Stone was plundered from Volubilis and from El Badi, the grand Saadian palace in Marrakech.

More than 25,000 unfortunate captives were brought in to carry out Moulay Ismail’s grandiose building works, labouring relentlessly by day and then being herded into subterranean prisons by night. Describing Ismail’s brutal treatment of his slaves – which included white slaves kidnapped from the coasts of England and Europe – the British writer Scott O’Connor, in Vision of Morocco, adds: ‘When the slaves died they were used as building material and immured in the rising walls, their blood mixed with the cement that still holds them together in its grip.’

Ismail’s megalomaniac vision left Meknes a graveyard of huge palaces and fortifications, and the imperial city now presents an impressive but sombre sight, built (literally) out of the blood and bones of those who once laboured upon it. The remains of some 30 royal palaces and 20 gateways, plus mosques, barracks and ornamental gardens can still be seen, magnificent and lunatic in scale.

Meknes remained capital until Moulay Ismail’s death in 1727, when his grandson and heir, Mohammed III, removed the court to Marrakech. Mohammed III destroyed a number of buildings as a parting shot, while the great earthquake of 1755 (which also flattened Lisbon) contributed to the slow ruin and decline of this once-great city.

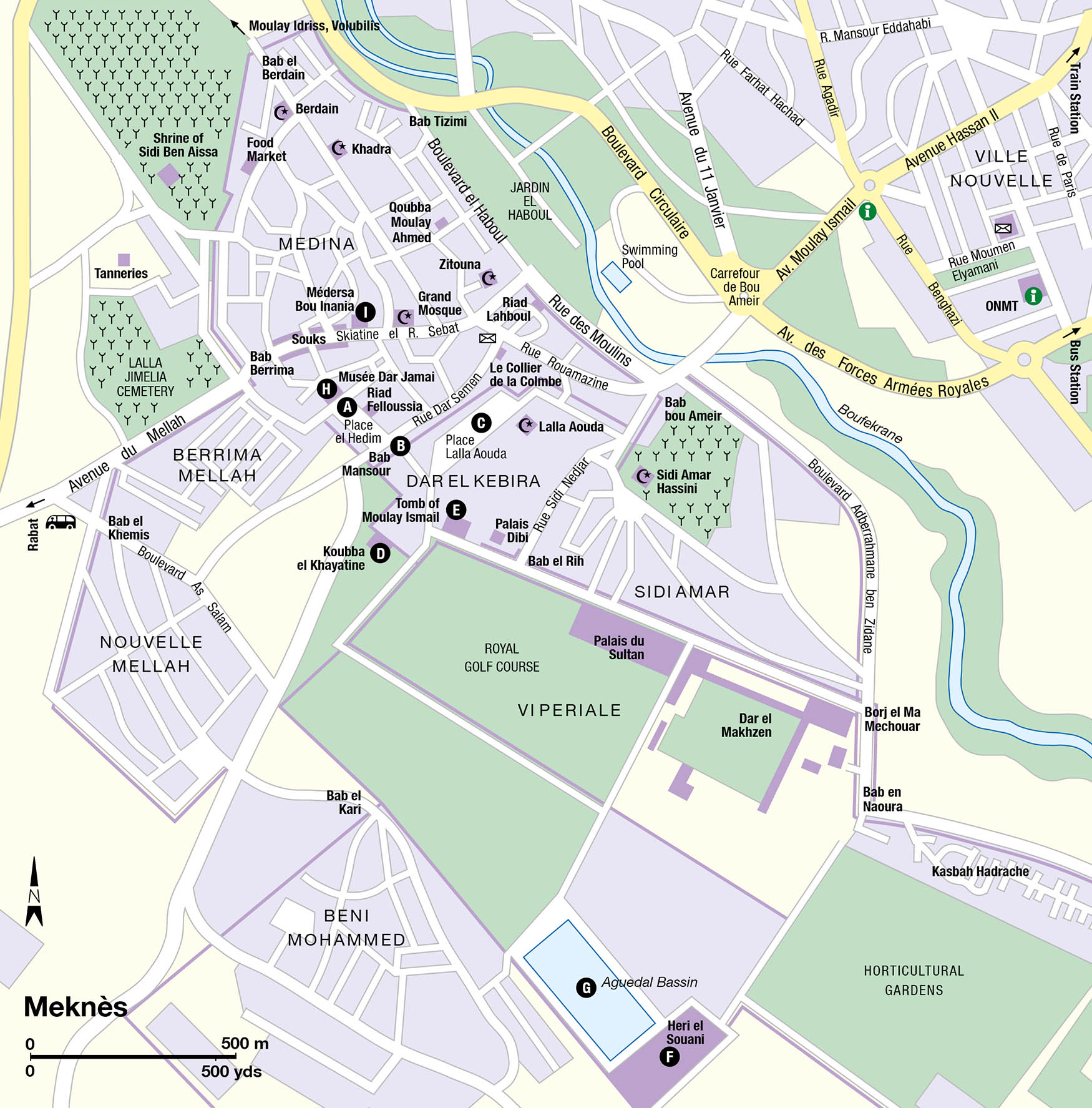

Place el Hedim and around

Begin a tour of Meknes on Place el Hedim A [map] (whose name translates as the rather sinister, but apt, ‘Destruction Square’), from where the medina spreads northwest and the Imperial City and Moulay Ismail’s tomb extend southeast. The square was formerly part of the medina but was razed to the ground by Moulay Ismail to create an approach to the main entrance of his palace via the Bab Mansour. Food stalls cling to the eastern side of the spacious space, large and rather empty by day, although it fills up towards dusk with miscellaneous musicians, snake charmers, story-tellers and other street performers, while the food stalls fire into life, shooting great clouds of smoke into the night air – like a miniature version of Marrakech’s celebrated Jemaa el Fna. The Dar Jamai Museum (for more information, click here) stands on the northwest side of the square.

Place el Hedim.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The area is dominated by the imposing Bab Mansour gateway B [map] flanked by two square bastions supported in part by incongruous white marble columns plundered from Volubilis, the squatness of the overall design relieved by the intricate swirl of blue and green tile work, which covers virtually every surface. A smaller but similar gateway, the Bab Djemaa en Nouar, stands a short distance further along to the right.

According to legend, the gate was designed by (and named after) a Christian renegade named El Mansour. Asked by the sultan whether he could ever improve the finished gateway’s architecture, the unwary El Mansour is said to have answered yes, whereupon he was promptly executed for his pains – although whether because the sultan feared he would take some new and enhanced design to a rival patron, or simply because El Mansour had failed to produce his best work in the service of the sultan, remains unclear. The story may well be apocryphal in any case, since the gateway wasn’t completed until after Sultan Moulay Ismail’s death in 1732, although it gives a nice impression of the Moulay Ismail’s ruthless personality, whatever its veracity.

Tours of the imperial city start here. Although a guide – picked up in Place el Hedim or around Mansour Gate – can be useful, the layout of the city is easy to grasp and it is possible to manage without one.

Turn left in front of Bab Mansour, then right through a smaller gateway about 50 metres/yds further along the walls, to reach the tranquil and spacious Place Lalla Aouda C [map]. Turn right and walk across to the back of the square to reach the Koubba el Khayatine D [map] (Ambassadors’ Hall; daily 9am–noon and 3–6pm), a simple pavilion thought to have been used as a place for receiving visiting ambassadors and for bargaining over the ransoms demanded for Christian victims of Barbary Coast piracy, in which Moulay Ismail had a controlling interest. More recently, the pavilion was used by tailors (khayatine) making military clothing.

Adjacent to the pavilion is a stairway leading into subterranean chambers that were once used as grain stores, though the macabre story goes that they were also a prison for thousands of white slaves captured by the Barbary pirates and brought to Meknes to help Moulay Ismail build the city. The chambers, which were blocked off by the French, who also added the skylights, once extended 7km (4 miles) in each direction.

Moulay Ismail’s tomb

Head through the brightly tiled gateway opposite, on the far side of the road, to reach Meknes’s chief attraction, the Tomb of Moulay Ismail E [map] (Sat–Thu 9am–noon, 2–6pm; donation). Restored by fellow Alaouite Mohammed V in the 1950s, it is one of the few shrines in Morocco that can be visited by non-Muslims. The others are the mausoleums of Mohammed V and Hassan II in Rabat and the shrine of Sidi Yahiya (for more information, click here) near Oujda. Entrance is via a sequence of high-walled courtyards – lavishly tiled and decorated, although despite the grandeur of the overall conception the detail is rather underwhelming compared with many other shrines and palaces in the country. Beyond these lies the inner sanctuary in which the tomb is situated – you’re not allowed into the sanctuary itself, although you can peek through the door for a glimpse of Moulay Ismail’s last resting place.

The Tomb of Moulay Ismail.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Moulay Ismail’s reputation for violence and cruelty does not seem to have diminished the reverence paid to him. It is perhaps odd that such a bloodthirsty ruler should have a shrine of such magnificence, and one that still attracts pilgrims from all over Morocco. People believe that his tomb has baraka (luck or magic), which will rub off on believers. A doorway off the mausoleum opens on to a private cemetery (no entry) containing the tombs of people who wished to be buried alongside this famous ruler.

The royal palaces

Continuing along the road past the mausoleum of Moulay Ismail brings you to the heart of royal Meknes. Past the small Bab el Rih gateway the road is hemmed in on either side by high, virtually unbroken walls, riddled with nesting birds, making it look like some gigantic open-air corridor. According to legend Moulay Ismail was fond of having himself conveyed along this well-concealed driveway in a carriage pulled by his eunuchs or concubines.

The walls on the left-hand side of the road conceal the Dar el Kebira, Moulay Ismail’s main palace complex. The palace was destroyed by his son, and its various gateways and the shells of its palace walls subsequently incorporated into a labyrinthine residential quarter, which you can explore by entering via the Bab el Rih. Beyond the walls on the right-hand side lies the Dar el Makhzen, a more modern palace, completed at the end of the 18th century. This has been restored and is used by the present royal family as an occasional residence, while its gardens and walls have been turned into an exclusive royal golf course. Entry is forbidden.

Aguedal Basin.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Heri el Souani

At the far end of the corridor road, behind the Dar el Makhzen, are the Heri el Souani F [map] (daily 9am–noon, 3–6.30pm), the vast granaries and store rooms of the royal complex and one of the most remarkable sights in the Imperial City. It’s a good 25 minutes’ walk to the granaries from the Tomb of Moulay Ismail and you may prefer to catch a petit taxi or (more picturesquely) to hire one of calèches (horse-drawn carriages) that hang out around the tomb.

The Heri el Souani comprise a sequence of immense high-vaulted chambers divided into 23 aisles, which were used as storerooms and granaries – the size of the complex designed to protect against the possibility of siege or drought. For a good overview of the complex, climb the stairs to the remaining part of the roof. Olive trees provide shade. The Aguedal Basin G [map], round the corner from the Heri el Souani (and visible from its roof), covers 4 hectares (10 acres) but, as with all the sights within the Imperial City, its abandoned grandeur creates a mournful and gloomy atmosphere. Moulay Ismail’s vision was mighty but the spaces he created were never filled – the scale was too huge.

The Royal Stables (not open to visitors), 3km (2 miles) further along the route in the quarter of Heri el Mansour, are the most extreme example of Moulay Ismail’s excess. They were built for more than 12,000 horses, each with its own groom and slave. The grain – sufficient for a siege lasting years – was stored below in the granaries, at a temperature kept constant by the thick walls. Ismail also constructed a channel providing fresh water for the horses without them having to move from their stalls. The crumbling remains still give an indication of the extent of decoration that once existed; tiles and zelliges are visible on pieces of partially overgrown wall. By and large, though, the place now belongs to goats.

Not far from here is the modern-day Haras Régional, a stud farm and training centre for Arabian horses. Experienced horsemen or women can take out temporary membership and help exercise the horses, but anyone can pay a visit. Some of the horses are pure Arabian, some Berber and others mixed.

More compact and delicate-looking than the thoroughbred, the Arabian is famed for its power as well as its beauty, but its most valuable asset historically was its endurance, a quality prized by the Bedouin, its human counterpart in weathering the hardships of the desert. A tribe’s horses were its chief pride, its partners in raiding and war. Years of working and living together (horses often bedded down in the family tent) forged a deep bond of affection between man and horse that transcended the usual human/animal relationships and inspired legends and poetry.

The Wine Industry

The low hills around Meknes are the main centre of Morocco’s wine industry, though the vine-growing area stretches from Rabat/Casablanca to Fez. The industry was set up by the French, who did the same in Tunisia and Algeria, both of which also continue to produce wine, in spite of the Qur’an’s admonishments against alcohol.

Over the last few years the variety and quality of Moroccan wines has greatly improved. Of the reds, Les Coteaux de l’Atlas, from Les Celliers de Meknès, is the most prestigious. Other good-quality Meknes reds are the Beni M’Tir Larroque Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot blend and the Comtesse de Lacourtabalise. Médaillon Cabernet, from the Domaine des Ouled Thaleb vineyard near Benislimane, is also among the best of the reds. Beauvallon Chardonnay, from the Beni M’Tir vineyard, and the Médaillon Cabernet Blanc, from Benislimane, are among the best whites.

Of the less expensive wines, the Meknes Vins de Cépage Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah are all quite drinkable, as are the Meknes Gerrouane Rosé and Gris, and the Benislimane Semillon Blanc and Cuvée du Président Cabernet Rosé. To buy wine in Morocco you need to go to a specialist shop in the ville nouvelle of a city or to one of the supermarket chains such as Marjane or Acima.

Fruit and vegetable stall.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The medina and souks

Returning to the Mansour Gate, enter the medina, at the west end of the Place el Hedim. The Dar Jamai Museum H [map] (Wed–Mon 9am–noon, 3–6.30pm), housed in the Dar Jamai, is discreetly positioned at the corner of the square beside the entrance to the medina. It is worth a visit to see the fine examples of Berber rugs, and also has an interesting collection of local artefacts and pottery. The building itself was built for Mohammed Ben Larbi Jamai, grand vizier at the court of Moulay Hassan (sultan 1873–94) by the same architect who built the Jamai Palace in Fez, though it is on a less grand scale. Some of the upper rooms are decorated and furnished to give an idea of domestic life in the 19th century. Like all the other grand palaces, it has an inviting garden filled with flowering shrubs and birdsong.

Dar Jamai Museum.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The main entrance to the medina and its central souk area street is right next to the museum. Follow the road into the souks for about 100 metres/yds (veering around to the right en route) to reach a T-junction. The main souk area lies off on your left from here, a dense and confusing area of tiny shops packed around even tinier alleyways, frequently reduced to pedestrianised gridlock by the sheer weight of local shoppers during busier hours. Much of the merchandise on display is relatively humdrum, although if you hunt around you may stumble upon more traditional areas devoted to carpets, textiles and slippers, as well as a small carpenters’ souk, permeated by the sweet smell of cedar and thuya wood. Continuing through the souk, you eventually emerge at the west end, site of most of the artisan markets. It is quite a scruffy area but has some interesting workshops, including basket-makers and saddlers, fabric sellers, metalworkers, cobblers and coppersmiths.

Return to the T-junction and head in the opposite direction – the streets here are calmer and emptier, and are also where you’ll find most of the medina’s tourist-oriented riads, shops and restaurants. A short walk brings you to the Great Mosque. Turn left here to immediately reach the Medersa Bou Inania I [map] (daily 10am–6pm), started by the Merinid Sultan Abou Hassan, who built the Chellah in Rabat and the Medersa el Hassan in Salé, but finished by Sultan Abou Inan (1350–58), builder of the Medersa Bou Inania in Fez. It is similar to other Merinid medersas, with a central ablutions fountain in a tiled courtyard, quarters on two levels for around 50 students and a prayer hall on one side. As usual, every inch of wall is painstakingly covered in stucco, zellige work and woodcarvings in abstract patterns and arabesques, which creates a mesmerising intensity designed to reflect and reiterate the greatness and oneness of God. Go up to the roof for good views of the surrounding area, including the green-tiled roof of the Great Mosque next door.

Beyond the medina

Outside the medina, beside the vast Bab el Berdain (Gate of the Saddlers) spreads a huge cemetery containing the shrine of Sidi Ben Aissa built in the 18th century (closed to non-Muslims), which is the focus of a moussem on the eve of Mouloud (the Prophet’s birthday) that changes every year. The event is one of the biggest moussems in Morocco, attracting members of the Sufi-inspired Aissawa Brotherhood from all over North Africa (see box).

The Aissawa Brotherhood

One of the best-known Sufi fraternities in Morocco is the Aissawa Brotherhood, which was founded in the 15th century by Sidi Ben Aissa and quickly spread throughout North Africa. Like other Sufi sects, it advocates music-induced trance as a means of drawing closer to God. One of the ways in which Sidi Ben Aissa revealed his mystical powers was through his immunity to scorpion and snake bites. He was said to confer the same magical powers on his followers. Once in a state of trance, they could eat anything, however grim, without ill effect. At one time, on the eve of Mouloud (the Prophet’s birthday), the date of their annual moussem, over 50,000 devotees would convene. Once in a state of trance, they would devour live animals and pierce their tongues and cheeks. Their rituals were similar to those of the Hammaadcha of Moulay Idriss, whose moussem is described in Paul Bowles’s The Spider’s House.

The Moroccan government has outlawed the most extreme practices of these cults, but their annual moussem – the largest in Morocco – still takes place, usually in April, in Meknes at the shrine of Sidi Ben Aissa, and they are very much involved in the everyday lives and rituals of their followers and of Moroccans in general. They perform healing ceremonies and attend circumcisions and are paid to capture snakes that have invaded houses.

The new and old mellahs (Jewish quarters) to the west of the medina and Place el Hedim have markets and souks of their own. This is one of the poorest parts of town, busy but run-down, with ramshackle buildings incorporated into the crumbling walls.

The Ville Nouvelle

Clearly separated from the imperial city of Moulay Idriss by the valley of the Oued Boufekrane, which runs through the valley between the city’s two halves, is the French-era Ville Nouvelle, built in the early in the 20th century. There is little of interest here, but it does have a good selection of hotels, restaurants and cafés. Although it is fairly lively by day, Meknes, both the Ville Nouvelle and the old, has relatively little going on in the evening compared with other larger Moroccan cities, including nearby Fez.

View over Moulay Idriss.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Roman ruins at Volubilis.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

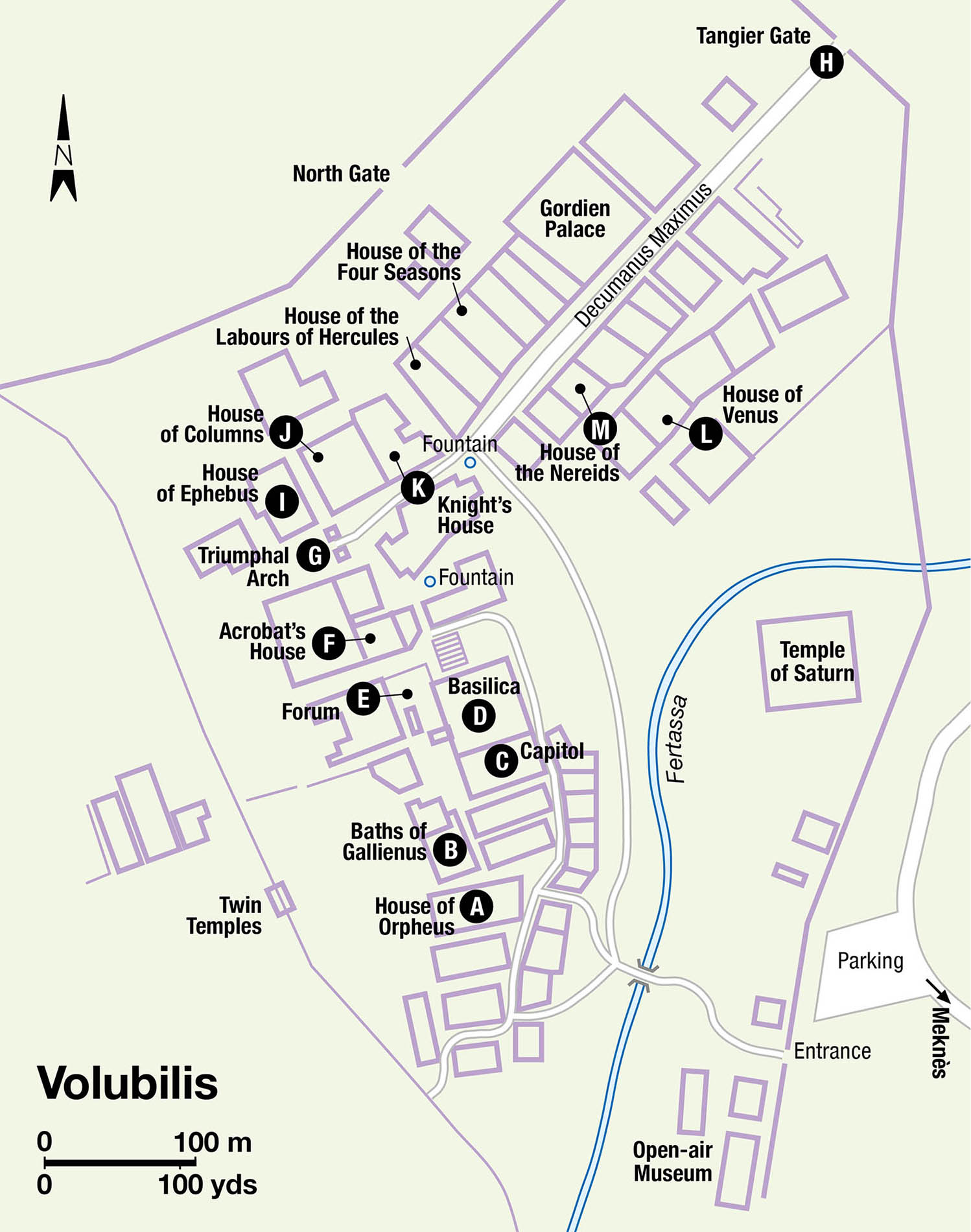

Set on a plateau around 30km (18 miles) north of Meknes, and visible for miles around, is the ruined city of Volubilis 3 [map] (daily 8am–sunset), formerly the most remote outpost of the Roman Empire in Africa, at the furthest reaches of that great empire. Moulay Ismail stripped the ruins of their marble for use in his own city at Meknes, while most of the important finds have been removed to the Archaeological Museum in Rabat. Even so, it remains one of the most impressive monuments of the Classical age anywhere in North Africa, particularly thanks to its superb mosaics, which remain safely in place,

It is frequently possible to have Volubilis to yourself: the best times to visit are late afternoon and early morning, when temperatures are cooler and coach parties have either gone or are yet to arrive.

The History of Volubilis

Volubilis was built on the site of a Neolithic settlement and an important Berber village, thought to have been the capital of the kingdom of Mauretania. From AD 45 Volubilis was subject to Roman rule, making it the empire’s most remote base. During this time, olive oil production and copper were the city’s main assets. The profusion of oil presses on the site confirms this. It benefited from local springs as well as the Fertassa stream running through the site. Most of the buildings date from the beginning of the 3rd century, when the number of inhabitants was probably around 20,000. By the end of the 3rd century the Romans had gone. After this, Volubilis maintained its Latinised structure, but when the Arabs arrived in the 7th century the culture and teachings of Islam took over. By 786, when Moulay Idriss I arrived, most of the inhabitants were already converted. He built a new town (Moulay Idriss) nearby, and Volubilis began to decline. Much later, in the 18th century, Moulay Ismail removed most of its marble to adorn his palaces in Meknes. Volubilis didn’t come to the attention of the outside world again until two foreign diplomats stumbled upon it on a tour of the area at the end of the 19th century. Excavations were begun during the French protectorate in 1915 and continue today, funded by the Moroccan government. In 1997, Unesco declared Volubilis a World Heritage Site.

Fact

The scale and splendour of the villas in Volubilis suggest it was a cultured and well-to-do town, as do the fine bronzes recovered from the site, now in the Archaeological Museum in Rabat (for more information, click here). Yet unlike other large Roman sites in North Africa, it had no theatre or stadium.

A tour of the ruins

Volubilis is small and easy to cover; the most important remains are clearly labelled and the arrows describe a roughly clockwise tour. Some of the main buildings have been half restored or reconstructed. The most remarkable finds include bronze statues (now in the Salle des Bronzes in the Archaeological Museum in Rabat; for more information, click here) and the amazingly well-preserved mosaics, many of which remain in situ. For purposes of identification, the houses are named after the subject of the mosaic they contain. All the houses follow the same basic structure: each had its public and private rooms. The mosaics usually decorated the public rooms and internal courtyards, the baths and kitchens being the private areas of the house.

Fact

The position, atmosphere and mosaics of Volubilis combine to make the site a worthwhile stop. Geckos running up and down crumbling walls, darting into invisible holes, occasional whiffs of highly scented flowers, the clear air and the silence on the plateau all enhance the magic.

Following a well-worn path through olive groves and across the small Fertassa River, clamber leftwards up the hill to the start of the site, where an arrow will direct you around to the left. The first house you come to on the clockwise tour of the site is the House of Orpheus A [map], the largest house in its quarter, identified by a clump of cypresses to the left of the main paved street. It has three mosaics: a circular mosaic of Orpheus charming the animals with his lyre, remarkable for its detail and colours, another of nine dolphins, believed by the Romans to bring good luck, and a third portraying Amphitrite in a chariot drawn by a seahorse.

From here, cut up to the modern square building containing a reconstructed olive press, one of several that have been found on the site. Next to it are the 3rd-century Baths of Gallienus B [map], originally the most lavish public baths in the city, as their proximity to Volubilis’s main civic buildings – the Capitol, Basilica and Forum – required. The grand houses in Volubilis had their own elaborate heating systems, providing hot water and steam for baths, but the public baths also provided a meeting place to chat, gossip, do business, exercise, and eat and drink.

From here, the street leads to the Forum (public square), Capitol and Basilica – an impressive collection of administrative buildings, which comprised the centre of the city. The Capitol C [map] is distinguished by a crop of freestanding Corinthian pillars and a flight of 13 steps on its north side. Originally the central area would have contained a temple fronted by four columns surrounded by porticoes. An inscription dates the temple to AD 217 and dedicates it to the cult of Capitoline Jove and Minerva.

Roman columns at Volubilis.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

The Basilica D [map] is a larger building beside the Capitol. It isn’t easy to see its structure now, but it would have been divided into five aisles (note the stumpy columns) with an apse at both ends. It doubled as the law courts and commercial exchange. The Forum E [map], which completes the administrative centre, is an open space that was used for public and political meetings. It is of modest proportions and nothing remains of the statues of dignitaries that would have adorned the surrounding buildings.

Between the Forum and the Triumphal Arch is the Acrobat’s House F [map], containing two well-preserved mosaics. The main one depicts an acrobat riding his mount back-to-front and holding up his prize. Another house nearby contained the famous bronze Guard Dog that is exhibited in the Archaeological Museum in Rabat.

The Triumphal Arch G [map] is the centre point of Volubilis – an impressive ceremonial monument, albeit serving absolutely no practical purpose. Contemporary with the Capitol, it was built by Marcus Aurelius Sebastenus to celebrate the power of the Emperor Caracalla and his mother Julia Domna. It is supported on marble columns and decorated only on the east side, while records and the inscription suggest it was formerly surmounted by a huge bronze chariot and horses.

The main paved street, Decumanus Maximus, stretches up to the Tangier Gate H [map], the only gate out of the city’s original eight which remains standing. Off the street are the ruins of many fine houses, the fronts of which were rented to shopkeepers, who would have sold their wares from shaded porticoes on either side – not unlike the layout of a typical Moroccan souk today.

Mosaic at Volubilis.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Further splendid mosaics can be found north of the Forum. The House of Ephebus I [map], for example, boasts a Bacchus mosaic, depicting the god of wine in a chariot pulled by panthers. A wonderful bronze statue of an ephebe (young man) wearing a leafy diadem was found in this house and is now in the Salle des Bronzes in the Archaeological Museum in Rabat (for more information, click here). The House of Columns J [map], recognisable by the remains of columns guarding the entrance to the courtyard, has an ornamental basin surrounded by brilliant red geraniums. The Knight’s House K [map], next to this, is in a poor state except for the stunning mosaic of Bacchus discovering the sleeping Ariadne, one of the loveliest sights of Volubilis.

Many of the larger houses off Decumanus Maximus contain well-preserved mosaics; in particular, don’t miss the House of Venus L [map] (marked by a single cypress tree) and the House of the Nereids M [map], a couple of streets in. The former contains stunning mosaics of mythological scenes, including the abduction of Hylas by nymphs and one of the bathing Diana being surprised by Actaeon. The House of the Nereids yielded the stunning bronze heads of Cato and Juba II – also in the museum in Rabat.

The well-worn path curls round behind the Basilica and Forum, leading back to the entrance, where one can adjourn for a mint tea in the café, and examine some of the statuary in the garden.

Moulay Idriss

Although hundreds of tourist buses visit Volubilis, only 1km (0.5 mile) away, only a few stop off in Moulay Idriss 4 [map], the small, picturesque whitewashed town clustered on a hilltop around a shrine to Moulay Idriss I, whose tomb rests here. Moulay Idriss is considered a holy town – at one time Christians were forbidden to enter – though it is relaxed and friendly today. Its chief appeal for non-Muslim visitors is its picturesque setting, which can be enjoyed over a mint tea in the square, Place Mohammed VI (where you can also park your car if driving). There are a few cafés and places to eat here, best of which is the charming Dar Zerhoune, and the mausoleum of Moulay Idriss is at the top of the square.

Moulay Idriss.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Set in the spur of the hills just east of Volubilis, Moulay Idriss appears to be a compact, predominantly white whole, but it is really two villages; the Khiber and the Tasga quarters join together around the mosque and shrine. Although Meknes is only 25km (16 miles) away, the town is seemingly oblivious to the 21st century, with few concessions to Western visitors.

Town history

At the end of the 8th century, Moulay Idriss el Akhbar (the elder) arrived in the village of Zerhoun. A great-grandson of the Prophet Mohammed, he had fled to Morocco to escape persecution and death. He stopped first at Volubilis, later building his town nearby, and set about converting the Berbers to the Islamic faith. He was well received by the mountain people, who recognised him as their leader, and he became the founder of the first Arab dynasty in Morocco. A year later he began founding Fez – a labour completed by Idriss II, the son of his Berber concubine, Kenza.

News of his popularity and success reached his eastern caliph, and an emissary was sent to poison him in 791. His dynasty lived on through his son, born two months after his death.

The cylindrical minaret of the Medersa Moulay Idriss.

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Exploring the town

The main square – more of a rectangle, in fact – opens out from the holy area. This is the busiest part of the town, especially around the tiled fountain, with several pleasant cafés. Opposite the entrance to the shrine makeshift stalls sell candles and padded baskets to present offerings. Nougat is a speciality of the town, as it is in many other places of pilgrimage in the Arab world.

The mausoleum itself was rebuilt by Moulay Ismail, who destroyed the original structure at the end of the 18th century in order to create a more beautiful building, which was then later embellished by Sultan Moulay Abderrahmen. Wooden bars (like those around the zaouia of Moulay Idriss II in Fez) demarcate the area around the tomb, indicating the point beyond which non-Muslims must not pass.

For a view (albeit distant) of the shrine, you’ll need to head up to one of the various viewpoints around town. The best views of the town are from the terrace of the Sidi Abdallah el Hajjam panoramic restaurant, above the Khiber quarter (although it’s tricky to find amidst the narrow streets hereabouts – you might want to take a guide). From here the structure of the town is clear: white and grey cubes cascade down to the point where the quarters merge beside the tomb and zaouia, the green-tiled roofs and arched courtyards of which are clearly visible. On the way up to the terrace, look out for the Medersa Moulay Idriss, embellished with what it said to be the only cylindrical minaret in Morocco, and very different from the usual square minarets of the Maghreb). Inspired by minarets seen in the Arabian Gulf, it was commissioned by a pilgrim returning from Mecca in the 1930s; its green ceramic tiles are inscribed with verses from the Qur’an.

Annual festival

As the location for the most important shrine in Morocco, Moulay Idriss is the focus for a huge annual moussem which takes place every August, attracting pilgrims from all over Morocco as well as several Sufi fraternities, such as the Aissawa, Hamaacha and Dghoughia (for more information, click here). The more extreme activities of these sects have been outlawed by the government, but it is rumoured that they continue in places unobserved.

The moussem is held after the harvest, usually beginning on the last Thursday in August. Originally a purely religious festival, it has come to include fantasias, singing, dancing and markets. The hillsides are covered with tents, and prayer and feasting continues throughout the festival. Tourists are tolerated, but it is a purely Muslim festival, and it’s probably sensible to visit during the daytime rather than in the evening.