CHAPTER TWO

A PRIMER ON AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

ONE OF THE CURIOUS THINGS about the way affirmative action works in higher education is that although it is widely misunderstood by the public and even many seeming “insiders,” scholars of all political stripes agree on many of its basic characteristics and effects. If you haven’t been following the literature, some of what we will describe in this chapter may shock you, but virtually none of it is controversial among scholars who have studied the relevant data (we will make note where particular features of the system are still uncertain or debated). What follows is a guide to its general operations and vocabulary; this will make the stories in later chapters easier to follow.

1. Contemporary affirmative action in higher education is primarily about racial preferences.

When the term “affirmative action” first came into general usage in the 1960s, it was understood to refer to organized efforts by government and other institutions to make sure that opportunities (e.g., benefits from federal programs or hiring by federal contractors) were truly open to all and did not simply pass through “old boy networks.” Affirmative action was a way of pushing these institutions to break their habit of bypassing (if not deliberately excluding) traditionally disadvantaged groups; in these early years the predominant focus was on opening access to African Americans. At universities in the mid-1960s it meant reaching out to counselors at black high schools in places such as Harlem or Boston’s Roxbury district or the South Side of Chicago, who had always assumed, with reason, that elite private colleges would never take their students seriously. It also meant sponsoring summer programs in which minority students were brought to campuses to meet with professors, explore the facilities, and hear talks about why they should seriously consider college in general and the host school in particular.

But starting in 1967 and 1968, first elite colleges and then professional schools shifted their focus from institutional reform to racial preferences. College and university leaders realized that outreach alone would bring no more than a small number of blacks to their campuses. Colleges—especially private colleges—that were accustomed to giving an admissions “plus” to all sorts of applicant characteristics, began to do so for blacks. Within a year or two they realized that even a conventional “plus,” like the points that might be given to a farm boy from Iowa, were not going to produce significant minority enrollment either. As a result, the racial preferences grew in size and soon became very large (as detailed below); they were extended from blacks to other racial groups, such as Native Americans, Hispanics, and sometimes southeast Asians, and they became more automatic. Soon large racial preferences overshadowed the old outreach efforts.

By 1980, more than three-quarters of the black students, and a majority of the Hispanic students at selective colleges and professional schools were there not because of some traditional form of outreach, but because they had received a preference (and often a race-based financial award as well).

2. Racial preferences are far more than mere “tie-breakers.”

As we explained in A Note on Terminology, we use the term “academic index” throughout this book to describe in a consistent way the test scores and grades that admissions officers heavily rely upon in making admissions decisions. For undergraduates, the index summarizes the SAT I scores and high school grades of students, with “0” meaning that a student received a 200 on each SAT I component and had a 0.0 high school GPA, and a “1000” meaning that a student received perfect scores on each SAT I component and had a 4.0 high school GPA. Many colleges and universities use some index of this kind; those that do not have some more informal way of comparing these key measures of prior academic success across their applicants.

Suppose that a college admissions officer reviews an applicant pool and sees that black applicants have academic index scores that are, on average, about 130 points below those of white applicants. The officer has been instructed to put together a student body that roughly mirrors the racial makeup of the applicants, of whom 9 percent are black. (These targets typically emerge from a consensus among the college president, a faculty admissions committee, and the dean of admissions.) To meet this target, the officer must somehow insulate the black applicants from direct competition with the generally higher-scoring Asian and white applicants. The simplest way to do this is to “race-norm” the academic index—that is, add 130 points to each black applicant’s index.

Now, college admissions officers and presidents and even some affirmative action scholars will not readily concede that colleges “race-norm” applications. That’s because explicit race-norming is pretty clearly unconstitutional under the Supreme Court’s 2003 decision in Gratz v. Bollinger, discussed in Chapter Thirteen. It is also illegal for schools to compare the academic index of scores of blacks and Hispanics only with those of other blacks and Hispanics and not with whites and Asians—a practice that, according to a recent survey described in Inside Higher Ed, is quite common at elite schools.

We have examined dozens of admissions datasets from many elite colleges and professional schools, and we almost invariably find that the racial gap in academic indices among applicants is very similar to the racial gap in academic indices among admitted students.

This implies that racial preferences will vary across racial groups, with blacks preferred over Hispanics, both groups preferred over whites, and whites preferred over Asians. Nationwide, the academic index of whites taking the SAT is about 140 points higher than the academic index for blacks (corresponding to a 300-point black-white gap on the current SAT I test, and a 0.4 GPA gap in high school grades), and it has hovered in that range for the past twenty years. Hispanics, in contrast, have an average academic index that is about 70 points lower than that of whites. The gap for American Indians is very similar to the black-white gap, and the academic index of Asians is about thirty points higher than that of whites. Something close to these differences will show up in most college applicant pools, and with racial preferences, similar gaps will carry over to the college’s enrolled student body.

These average differences across races in academic preparation carry over to virtually all of the academic measures that admissions officers rely on. There are, for example, substantial racial differences in the proportion of students who have taken AP classes, how many they have taken, and what scores they have obtained. Through the use of racial preferences, all of these differences become replicated in the student bodies of colleges and universities.

A number of scholars have carefully documented these gaps. For example, Thomas Espenshade, a leading expert on (and supporter of) affirmative action, and his coauthor Alexandria Walton Radford obtained academic data on a large number of students at a sample of selective, mostly private colleges. In their 2009 book on race in higher education, No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal, they reported that black applicants received “an admissions bonus . . . equivalent to 310 SAT points” relative to whites and more relative to Asians. This translates to 155 points on our academic index. Other studies focus on the vastly greater chance that a black applicant has of being admitted compared with a white applicant with the same academic index score.

There are two important points here. First, racial preferences are not remotely close to being the “tie-breakers” they are sometimes claimed to be. They require admissions offices to give priority to minority applicants over hundreds or thousands of white and Asian applicants with substantially higher academic indices. And second, because of the large differences in average academic indices across racial lines, large racial preferences follow ineluctably if elite schools want student bodies whose racial mix reflects their applicant pool. (We explore the sources of and possible cures for racial difference in pre-college learning in Chapter Seventeen.)

3. Virtually all colleges and universities that use racial preferences have either an explicit or an implicit weight assigned to race.

Every analyst who has studied actual data on admissions at selective colleges or professional schools understands that these schools not only use large racial preferences; they also use them consistently. That is to say, the effect of the preference at these schools is essentially equivalent to adding a certain number of points to each black student’s test scores or GPA. Or, to put it differently, there is some range of academic credentials in which white and Asian applicants are almost certain to be denied, whereas blacks and American Indians are almost certain to be admitted and Hispanics are a coin toss.

These schools often refer to their admissions processes as “holistic,” as though each file is deeply meditated upon and each admissions decision is more intuitive than mechanical. (As we shall see, current Supreme Court doctrine nearly requires schools to at least pretend this is the case.) At most large schools such descriptions are completely fanciful; admissions are driven by fairly mechanical decision rules. But even at schools that truly do make decisions on a case-by-case basis, there is some kind of systematic heuristic— a detailed mental sorting system—that guides choices. If we could sit down with the admissions staff and give them a series of hypothetical candidates who differed only on one or two characteristics, we could reconstruct the implicit weight given to a well-written essay, an enthusiastic letter of recommendation—or the applicant’s race. Given the observed results of admissions decisions, we know that such an implicit weight exists and that, for race, it is generally very large indeed.

4. Racial preferences produce a “cascade effect.”

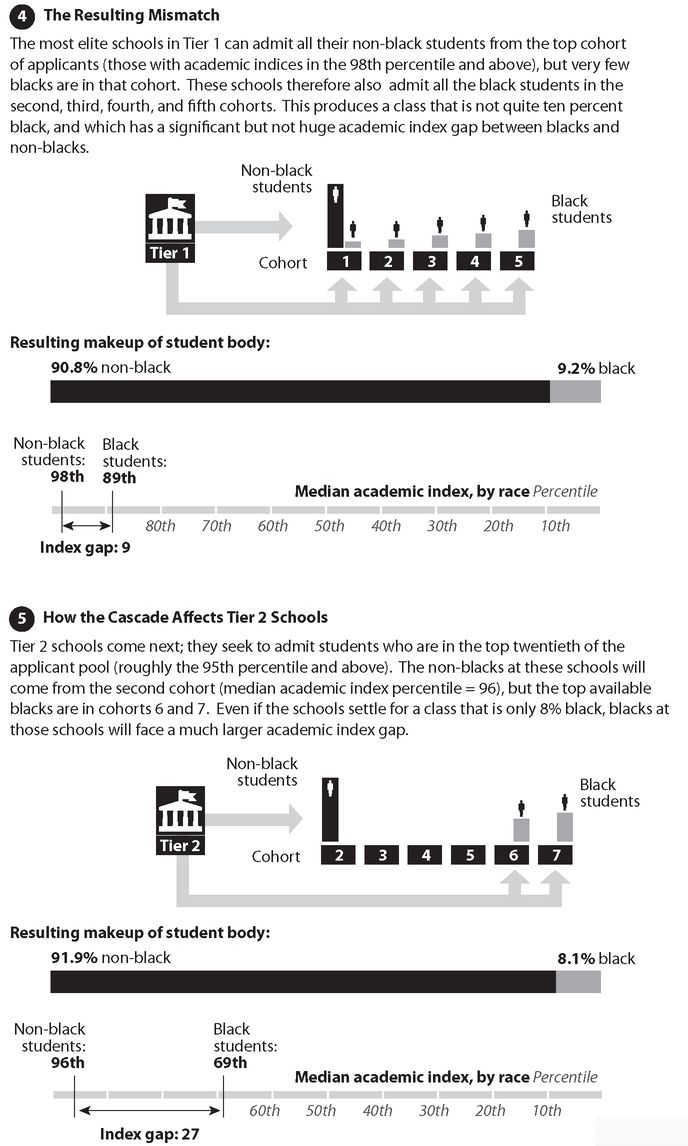

One striking feature of our system of preferences is its tendency to cascade like a row of dominoes. The elite schools get their pick of the most academically qualified minorities, most of whom might have been better matched at a lower-tier school. The second tier of schools, deprived of students who would have been good academic matches, must then in turn use preferences to produce a representative student body, and so on down the line.

Figure 2.1 illustrates the cascade effect for black students by showing the relative supply of blacks to whites at various levels of the academic index in the national pool of college applicants in 2008. In this very simplified example the most elite colleges set racial diversity goals, admit the blacks with the highest academic indices, and then continue using preferences as large as necessary to reach down into the black pool until they achieve their admissions goals, a process that absorbs the top five cohorts of blacks. The second tier of colleges start where their more elite competitors leave off, but even their strongest black admits will have academic indices well below the white average. To avoid too large an academic index gap between whites and blacks, the second-tier schools end up admitting a smaller proportion of blacks than the top-tier schools, but those blacks nonetheless have a larger academic index gap (and thus more vulnerability to mismatch) than do their counterparts at the most elite schools. And so on down the line. Only when one drops below the midpoint of academic index distribution does the supply of black candidates become large enough to start dampening the cascade effect.

We can draw two important lessons from

Figure 2.1. First, the cascade effect multiplies with the number of institutions using—and the number of students receiving—racial preferences. In Tier 2 on down, it’s the case that if higher-ranked schools practiced strict race neutrality, then schools in every lower tier would be able to use much smaller preferences, or none at all, to achieve their racial diversity goals. Second, the cascade effect amplifies the academic index gap as it sweeps across the tiers. Because the most elite schools “go first,” they are in the unique position of being able to admit both the minority students who qualify for their schools without preferences and the best students who can qualify with relatively small preferences. Tier 2 schools must reach much further down into the pool of students and thus end up with a larger black-white academic index gap. And so on.

Figure 2.1 is an enormous oversimplification of the actual dynamics of competitive college admissions. Schools do not, of course, rely solely on academic indices or their equivalents to select students; therefore, their student bodies are somewhat more academically heterogeneous than our model suggests. Nor do all or even most students attend the most elite school that will have them. Nor would a law requiring race-neutrality produce the tiny representation of blacks at the most elite schools that our model suggests, because other mechanisms of increasing diversity (such as socioeconomic or athletic preferences) would offset race-neutrality to some degree.

These caveats notwithstanding, the cascade effect is a dominant aspect of racial preference systems. It clearly does multiply the scale on which preferences are used and effectively forces second- and third-tier institutions (however defined) to use larger preferences than do the schools at the very top.

Thus, the most elite schools are thrice blessed. Because they are the first movers in this process, they can (a) enroll larger numbers of minorities than their less elite counterparts; (b) harm them less, because the credential gaps at those schools are more modest than they are at the next few tiers; and (c) often boast excellent outcomes for their minority students who are, after all, coming in with very impressive credentials.

Although academics at very elite institutions generally don’t appreciate this dynamic, it does help explain why many of the most ardent defenders of racial preferences hail from those very schools. Looking around their own campuses, they simply do not see anything like the full magnitude of the problem that their use of racial preferences creates for the broader pool of students and schools.

5. It’s not so easy to make up lost ground, and it’s more common to fall behind.

Two interrelated myths pervade affirmative action discourse. One is that standardized tests like the SAT I and the ACT or other measures of achievement like high school grades are biased against minorities and understate their academic ability. The other is that when colleges and universities use preferences, they are finding and selecting minorities who, despite their low academic indices, have such strong academic potential that they will perform at levels comparable to other students at the college if only given the chance.

These myths are cultivated by many higher education leaders, who often make the sort of gauzy, misleading observations that Duke president Richard Brodhead made in March 2012 when responding to evidence that blacks at Duke were dropping out of science majors at a high rate. “When we offer admission to a student,” Broadhead said in a prepared speech, “we do so in confidence that the student will succeed and thrive. We pay attention to test scores for what they are worth but we know they are an imperfect measure: at the end of the day, Duke’s goal is not to reward high test scores, but to recruit and train the level of talent that will make the highest degree of contribution to the university community and our future society.”

In fact, Duke and virtually all other elite universities admit students primarily on the basis of student grades and scores (which is why, for example, nearly all whites and Asians at Duke have SAT scores at the 90th percentile or above). They do so because of the predictive power of these academic credentials (and because the eliteness of a school is largely gauged by the credentials of its students). And no knowledgeable scholar contends that students who receive racial preferences routinely outperform those credentials—although, of course, some students do. On average, the academic index of black and Hispanic students admitted with large preferences overpredicts their academic performance in college; in other words, students tend to do somewhat worse than whites with the same academic index.

No one can know in advance whether a particular individual will succeed or fail. But university leaders know that when they admit a group of students with large preferences, the average grades of those students will be well below those of their peers. Depending on the size of the preference, most members of the group will end up in the bottom quarter, bottom fifth, or even bottom tenth of their class. Nor do students with preferences who start out badly tend, on average, to catch up during college; their class rank remains static or declines further. If you are grouped with students who generally have stronger academic preparation, it’s likely that you will struggle and often you will fail.

We cannot reiterate too often: The vast majority of students who are admitted with large racial preferences are talented people who are well equipped to succeed in higher education. The issue we examine in this book is not whether these students should go to college but rather which college environment will best promote their success. If they attend somewhere based on preferences, they will be at a relative disadvantage. The biggest question—and the hardest one to answer with confidence—is Will this relative disadvantage in the classroom turn for many into an absolute disadvantage in life?

The points we have just discussed are foundational in that they shape the way racial preferences operate through much of higher education. On some other important matters there is less consensus, so we pose these as questions rather than settled statements.

6. How far down the hierarchy of schools do racial preferences cascade?

We frequently use the terms “elite” or “selective” in describing colleges and other academic programs that apply racial preferences. But what does that mean? Are preferences limited to a small fraction of schools, or are they fairly pervasive?

Perhaps the most thorough published studies of this issue were done in the 1990s by Thomas Kane, now a policy scholar at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Using 1982 data on a national sample of high school and college students, Kane found that race played a decisive role in admissions only at the most selective fifth of four-year colleges (which translated into about four hundred institutions out of two thousand in his sample). At these schools the size of racial preferences was quite large (equivalent, for blacks, to about two hundred points on our academic index), but Kane found that the vast majority of four-year colleges were not selective at all, thus making race (or other individual characteristics) irrelevant.

Our analysis of more recent and more comprehensive data suggests that the proportion of four-year colleges using racial preferences has probably grown to perhaps a quarter or 30 percent of the total. Examining data from the 2007 and 2008 admissions cycles at a wide range of public universities, we consistently found racial preferences across nearly all institutions that have a median SAT of 1100 or higher. This includes most or all of the very large, flagship state universities. Taking institutional size into account, perhaps as many as 30 to 40 percent of all undergraduates attending four-year colleges are going to schools that use large racial preferences.

Moreover, as

Figure 2.1 shows, the cascade effect pushes the mismatch problem across the whole spectrum of colleges. Even if only the most elite quarter of colleges (the top five tiers in the figure) use preferences, they still leave a large preparation imbalance between whites and blacks attending non-selective colleges. The cascade thus means that mismatch is a potential issue for nearly all blacks, and a great many Hispanics and undergraduates.

Preferences are even more pervasive at law schools and medical schools, perhaps because the competition for spaces at these schools is much greater. Our research has shown that more than 80 percent of law schools make significant (and often massive) use of racial preferences; a variety of evidence suggests the proportion is about the same at medical schools. We suspect that most doctoral (e.g., PhD) programs use racial preferences as well, but the information here is too scattered to draw a firm, quantified conclusion.

7. How do racial preferences compare with other sorts of preferences used by colleges, such as those for athletes and legacies?

Liberal arts colleges extend admissions preferences to all sorts of applicants for a wide variety of reasons. At least some scholars have argued that athletic and legacy preferences are comparable in size to racial preferences. If preferences cause mismatch, why are we focusing on racial preferences?

The reasons include the long-standing visibility of racial preferences as a hotly contested political and legal issue that has roiled state and national politics and repeatedly engaged the Supreme Court, the nation’s tortured history on issues of race, plus the unavailability of much reliable data on legacy and athletic preferences. The vast majority of datasets about higher education and college students—including nearly all those we draw from for this book—identify the race of students but do not identify whether a student is a legacy or received an athletic preference. We therefore know a great deal about the operation and effects of racial preferences but relatively little about athletic and legacy preferences. The limited data we have seen and the secondary sources that discuss legacy and athletic preferences often tell contradictory stories as to the size and pervasiveness of these preferences. Such data as we have seen plus much anecdotal evidence suggest, if inconclusively, that legacy preferences and many athletic preferences affect many fewer students, and are on average significantly smaller than racial preferences.

What does seem true is that the mismatch operates in much the same way across racial lines. Whenever we have documented a specific mismatch effect, we have found that it applies to all students who have much lower academic indices than their classmates. One can imagine reasons why mismatch might be mitigated in the case of some athletes (because the school provides them with targeted academic support) or some legacies (because they received a stronger secondary education than their numerical indices suggest), but our limited evidence suggests that these groups, when they receive large preferences, are vulnerable to the same mismatch effects we document for racial minorities.

As the reader will see, we believe that a key antidote to mismatch is a dramatic increase in the transparency of information from colleges and universities on the size and effects of all preferences. We argue that this would go a long way toward corralling harmful practices in all preference programs.

8. Do universities even attempt to use racial preferences to create pathways to opportunity for the disadvantaged?

Much of the rationale for racial preferences lies in their putative capacity to improve social mobility, make America a more just society, and bring diverse life experiences and perspectives to university campuses. In the early years of racial preferences—the late 1960s and early 1970s—the main beneficiaries were African Americans who were the first in their families to attend college. As time has passed, however, college and university admissions preferences have become more and more diffuse in their targeting. A wide range of racial groups now receive preferences, including American Indians, Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and southeast-Asian Americans. A very high proportion of blacks—in some cases 70 percent—receiving preferences at elite colleges are either mixed-race Americans or foreign-born blacks. And a majority of African Americans receiving preferences at elite colleges and law schools themselves come from affluent families, usually with two college-educated parents.

Indeed, all or almost all recipients of large racial preferences are elevated over the large supply of less-affluent Asian and white students with stronger academic credentials. Scholars also have found that “because elite private colleges and universities have access to enough white students in other ways, they intentionally save their scarce financial aid dollars for students who will help them look good on their numbers of minority students.” One result is that “the low SES (socioeconomic status) benefit at private colleges is reserved largely for nonwhite applicants” and that “for white students, admissions chances . . . are smallest for low and high SES applicants and largest for white applicants from middle- and-upper-middle-class backgrounds.”

The reasons for this shift are complex. In part, we believe, it is because of the mismatch problem itself. College officials often observed that early cohorts of affirmative action admits had disastrous outcomes, and they found themselves caught between their commitment to diversity and the need to improve success rates. They solved this dilemma by creaming the most accessible and talented minorities they could find, who were generally not those with the greatest disadvantage.

It is important to note, too, that there is some disagreement about just how affluent the typical racial-preference beneficiary is. As we shall explore in more detail in Chapter Sixteen, it is hard to deny that at elite law schools the overwhelming share of blacks receiving large preferences come from relatively affluent backgrounds. However, some liberal arts colleges pay close attention to socioeconomic disadvantage, and the data is more mixed. There is no question, however, that one of the most telling critiques of contemporary racial preferences is that they do little to bring in students of modest means.

9. Do racial preferences single out Asians for particularly unfavorable treatment?

As we discussed earlier (point 2), racial preferences vary with the size of the test score gap: blacks receive larger preferences than do Hispanics because in the typical applicant pool, blacks have lower average academic indices. We do not think experts dispute this. But a corollary of this point is hotly disputed: Because East-Asian Americans and Asian-Indian Americans in most applicant pools have higher average academic indices than do white applicants, do schools discriminate against Asians to keep their numbers down?

At most undergraduate schools for which we have data, students with marginal credentials (by the school’s admissions standard) are significantly less likely to be admitted if they are Asian. When such findings are pointed out, university officials often respond that this occurs because Asian American applicants tend to have weaker “soft” credentials than do similar whites.

Perhaps. But Princeton sociologist and affirmative action supporter Espenshade and his coauthor Chang Y. Chung concluded that if racial preferences were eliminated at highly selective schools across the nation, “Asian students would fill nearly four out of every five places in the admitted class not taken by African-American and Hispanic students, with an acceptance rate rising from nearly 18 percent to more than 23 percent.”

In later chapters, we will occasionally note evidence of discrimination against Asian American applicants. We suspect that discrimination against Asian Americans is spreading. In our view, a system that makes fine racial distinctions among groups that have weaker credentials than whites will inevitably tend to do the same thing with groups that have stronger credentials than whites. The instinct to pursue racial balancing across the board is almost irresistible.

10. Would credential disparities disappear if admissions preferences ended?

A central argument in this book is that when students are surrounded by peers with much stronger academic preparation, their learning suffers and their outcomes are usually worse. Some commentators respond that this mismatch is inevitable—that even if schools abandoned all racial preferences, minority students’ lower credentials would still show up in student bodies selected through race-neutral methods.

Simulations show that this argument is not true if schools select students strictly on the basis of academic credentials. For example, in

Figure 2.1 we show data on “slices” of the applicant pool based on academic credentials. We see that it is easy to demonstrate that black students in most of these academic slices have average credentials identical to whites even though the overall black distribution is lower.

But that is not quite the end of it. Most academic programs take factors other than measurable academic preparation into account, such things as family background, leadership skills, community service, and writing ability. To the extent that these other factors do not correlate with academic credentials but do shape admissions, race-neutral admissions will not eliminate race-related gaps in preparation. For example, if a school bases half its admissions decisions on quantifiable factors like SAT score and high school grades and half on factors completely unrelated to academic preparation, then race-neutrality will eliminate only about—you guessed it—half of the black-white gap in preparation. Few institutions place this much weight on nonacademic factors, but some do, and more would be tempted to modify admissions to consider nonacademic factors more heavily if they were legally barred from explicitly considering race. This has actually happened in at least some states that ban universities from taking race into account.

Thus, it is the case that eliminating racial preferences will largely eliminate racial disparities in student preparation if an academic program selectively admits students based primarily on their academic credentials. But it is also the case that programs that use extensive “race substitutes” or other nonacademic criteria in admissions will preserve significant disparities in preparation across racial lines, even if those programs are formally race-neutral. The moral is that, to the extent mismatch is a serious problem, it cannot be solved entirely by something as simple as a ban on racial preferences. We think there are better, smarter solutions.