The Great Ming and East Asia: The World Order of a Han-Centric Chinese Empire, 1368–1644

Jinping Wang

In November 1367, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–98) issued a Northern-Expedition proclamation when he sent two of his most brilliant generals to attack the remaining Mongol forces of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) in north China. The proclamation conveyed important messages about a new imperial dynasty Zhu Yuanzhang was about to build, emphasizing his determination to rid China of Mongol influence and restore the civilization of the Han Chinese (deriving from the name of the Han Dynasty, 206 bce–220 ce), who were and remain today the majority ethnic group in China. A few months later, having forced the last Yuan emperor to flee Beijing for the steppe and having eliminated most of his domestic rivals, Zhu Yuanzhang pronounced himself emperor of the new dynasty of “Great Ming” (Daming 大明, meaning “Great Brightness”) in Nanjing in January 1368. He also named his reign Hongwu (“Expansive Martial” 洪武), and modern scholars often refer to him as Emperor Hongwu or just Hongwu. In the early years of his reign, Hongwu continuously sent edicts to rulers in frontier regions and neighboring states such as Annam (modern Vietnam), Korea, and Japan. Employing language similar to that used in the 1367 proclamation, he claimed legitimacy as a new Chinese emperor and demanded allegiance. These documents, the 1367 proclamation and the subsequent edicts, set the basic tone for the worldview of the new Ming Empire.

This worldview stressed the empire’s territorial unity under the centralized rule of the Zhu royal family, who identified themselves as Han Chinese and followed an official orthodoxy very closely associated with Confucianism. This worldview highlighted two different approaches to foreign relations between Ming China and other entities. One approach was based on a Sino-steppe demarcation, regarding China as geopolitically and culturally separate from the world of the northern steppe controlled by the Mongols. The other approach was oriented around a hierarchy in which China was a hegemonic suzerain state and non-Chinese entities were subordinate vassal states that acknowledged the Chinese supremacy.

Throughout his reign, Hongwu employed these approaches to forge the Ming into the Han-centric Chinese empire he envisioned, an imperial empire that openly promoted the supremacy of Han-Chinese styles of governance, institutions, and culture. Hongwu’s son Zhu Di (Emperor Yongle, r. 1402–24), after usurping his nephew’s throne and moving the capital to Beijing in 1415–21, differed from his father in taking more aggressive and expansionist approaches to reshaping the Ming Empire in terms of foreign relations. Yongle also introduced new modes of imperial governance and set into motion such sweeping changes that he was later seen as the “second founder” of the Ming dynasty both by his successors and by historians.1

The diversified traditions of empire-building established by the two founders strongly foreshadowed the ways in which later Ming rulers understood and governed their empire. Meanwhile, the empire was continuously changing in accordance with variations in individual rulers’ desires, capabilities, and government policies and practices, as well as in response to fluctuating geopolitical situations within and beyond China. After the mid-sixteenth century, the integration of domestic and global economy tied the destiny of the Ming Empire closely to world developments, forcing the Ming rulers to adjust their policies to cope with emerging crises both at home and at their borders.

This chapter emphasizes the crucial importance of the Hongwu and Yongle emperors in shaping the characteristics of the empire. Specifically, it discusses how Hongwu laid the cornerstone of the empire’s political legitimacy, how he and Yongle established the empire’s foundations for governance, frontier management, and foreign relations, and how these foundations were perpetuated or changed throughout the rest of the dynastic history. The material presented here aims to demonstrate how the Ming rulers defined their empire, and how their perceptions interacted with political, economic, social, and cultural changes over time. The chapter also pays particular attention to the ways in which the Ming inherited the legacies of earlier Chinese empires and of their immediate Mongol predecessors, the Yuan dynasty. Proceeding chronologically, this chapter examines the Ming Empire from four perspectives: political legitimacy, imperial governance, frontier managements, and foreign relations.

Zhu Yuanzhang used two crucial Chinese discourses—the distinction between hua (“Chinese,” but more literally “brightness” 華) and yi (“barbarians” 夷), and the Mandate of Heaven—to legitimize his regime as a new Chinese empire. The 1367 Northern-Expedition proclamation provides the best illustration of the uses of these discourses. It begins with an elaboration of the discourse of Hua-Yi distinction: “Ever since the ancient times, rulers have governed All under Heaven. It has always been the case that China occupied the center to bring the barbarians under control, while barbarians remained in the peripheries, respecting and submitting to China. I have never heard that barbarians occupied China and governed All under Heaven.”2

The Hua-Yi discourse stressed the demarcation between Chinese and non-Chinese along the lines of ethnicity, culture, and geography, and highlighted Chinese cultural superiority. It developed in the Warring States period (476–221 bce) and was integrated with the notion of “All under Heaven” (Tianxia 天下)—meaning moral uniformity of the world—in the Han dynasty to shape the traditional Chinese worldview. In this worldview, China, where the Han Chinese lived and Han-Chinese culture flourished, is the center of the world, hence the “middle kingdom” (Zhongguo 中國). “All under Heaven” also refers to the extended Chinese world that included fluctuating groups of non-Han peoples, who were “organized through a grade system similar to that of Chinese society.”3 The Chinese emperor is superior to all rulers of those non-Han peoples, or “barbarians,” who show their respect and accept their status as vassals by submitting periodic tribute to the Chinese throne.4 In this sense, “All under Heaven,” as the highest level of sovereignty in the imperial Chinese context, is the notion in classical Chinese that most closely resembles the concept of empire in English.

Since the Han dynasty, a Chinese dynastic empire based on the “All under Heaven” worldview can be understood in both internal and external dimensions. Internally, it must be a dynastic-state ruled by one royal family, and it must maintain a unified rule of China proper, the region that has traditionally been understood as China (though its geographical boundaries have changed overtime). The ideology of “Great Unity,” as Yuri Pines eloquently argues, constitutes the political legitimacy for a Chinese dynastic empire throughout China’s imperial history.5 Externally, the Chinese empire must maintain a web of functioning hierarchical relations with neighboring non-Chinese entities that submit to China through a tributary system. The ruling dynasty of a tributary state had the privilege (or obligation) of sending periodic tribute and trade missions to the capital of the Chinese empire. In return, the Chinese empire recognized that dynasty as the legitimate and rightful rulers of that state. As Hiroshi Danjō points out, the geographical concept of All under Heaven as a Chinese dynastic empire has both a narrow and a broad sense: the former refers to the actual territory of a Chinese dynasty, while the latter refers to the combination of Chinese and non-Chinese worlds.6

Among earlier imperial empires, only three dynasties achieved the de facto status of an “All under Heaven” empire in its broad sense by territorially unifying the Chinese and non-Chinese worlds. Both the Han dynasty—ruled by Chinese—and the Tang dynasty (618–907)—whose ruling house was half Chinese but emphasized their Chinese identity—expanded the Chinese territorial rule into the non-Chinese world (e.g., central Asia), establishing Sino-centric “All under Heaven” empires. Subsequently, after three centuries of fragmentation, the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), for the first time, brought China proper, the formidable steppe, and many other regions of China’s frontier again into a unified empire. Yet, not only was the Yuan ruled by the Mongols—northern barbarians in the Chinese view—but it also reversed the hierarchical order between Chinese and non-Chinese, categorizing the Mongols as the most superior class and Han Chinese as the lowest. The Yuan was thus not a Sino-centric but a Mongol-centric empire over All under Heaven.

From the traditional perspective of the Hua-Yi distinction, the Mongols turned the Chinese world upside down, and the right thing for the Chinese to do, therefore, was to reestablish Han-Chinese supremacy over non-Chinese. This argument was precisely what many late Yuan rebel leaders, including Zhu Yuanzhang, advocated in order to mobilize Han Chinese against the Mongols. Zhu Yuanzhang used the Hua-Yi discourse to characterize his anti-Mongol rebellions as a pivotal Chinese mission to expel the barbarians. As he articulated in the 1367 proclamation:

Among millions of people, a sage was to be born to expel the northern barbarians, recover [the land of] Central Brightness, set up the principles and essentials of government, and bring relief to the populace ... For China’s people, Heaven surely commands a Chinese to bring peace to them. How could barbarians rule China? I fear that the Central Land has long been polluted by the stink of mutton and the people have been troubled. Therefore, I led heroic men sparing no efforts to making a clean sweep. My goal is to expel the Mongol barbarians, eliminate violence, make the populace all have their places, and cleanse China of humiliation.7

The Hua-Yi discourse undeniably appealed to the Han ethnocentric sentiment that was boiling over in late Yuan China. Zhu Yuanzhang’s campaign slogan, “Expel the northern barbarians, and recover the land of the Central Brightness [i.e., China],” became so influential that the modern Chinese nationalist Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925) later borrowed it in the early twentieth century during his revolution against the Manchu Qing Empire (1644–1911).

In addition to the Hua-Yi discourse, Zhu Yuanzhang, as the 1367 proclamation demonstrates, also employed the Confucian discourse of Mandate of Heaven, with particular emphasis on the sage-king ideal, to consolidate his claim of being the sole legitimate ruler of China. Zhu Yuanzhang claimed that the Yuan’s legitimacy as a Chinese dynasty was “given by Heaven” after the previous Song dynasty (960–1276) lost Heaven’s blessing, but that the luck of both the Song and the Yuan dynasties had run out. Heaven now brought a sage—meaning Zhu Yuanzhang himself—to restore the proper order in China.8 This statement unmistakably invokes the notion of sage-kings based on the influential Confucian text Mencius, which states, “Every five hundred years a true King should arise.”9 Before the Northern Expedition Zhu Yuanzhang allegedly had the following conversation with a Confucian scholar named Xu Cunren: “The Majesty said, ‘Mencius said that every five hundred years a sage-king was bound to rise.’ Cunren responded, ‘It has been five hundred years since Emperor Taizu of the Song Dynasty. Now it is the time to unify All-under-Heaven under one monarchy.’”10 This conversation has two implications. First, Emperor Taizu, the founding emperor of the Northern Song (960–1127), was one of China’s sage-kings, while Zhu Yuanzhang was the next one who gained Heaven’s blessing to establish a unified Chinese empire. Second, although the Yuan founder Qubilai Khan (r. 1260–94) gained the Mandate of Heaven, he, as a northern barbarian, could not be a sage-king. Adopting both the Mandate of Heaven and the sage-king discourses, therefore, legitimized a non-Chinese dynastic founder like Qubilai Khan as Heaven’s chosen ruler but effectively denied him status as an ideal ruler for a Chinese dynastic empire.

The early Ming regime took great pains making its claim to rule All under Heaven by emphasizing its achievement in unifying Chinese territory and reestablishing tributary relations with its neighboring entities. In the first decade of his reign, the Hongwu emperor sent foreign rulers many edicts, which presented an exhausting list of domestic rivals he had eliminated and massive territories his regime had gained. In these edicts, Hongwu repeatedly stressed what he had achieved to “restore China’s traditional territory.”11 As Wang Gungwu has correctly argued, Hongwu’s strong interest in developing tributary relations with neighboring states in his early reign was largely due to his purpose of seeking neighbors’ acknowledgment of his legitimacy.12 That acknowledgment itself contributed to consolidating the legitimacy of the Ming as a new Chinese empire.

In addition to the territorial and foreign-relation dimensions, Hongwu’s construction of the Ming Empire’s legitimacy also had historical and cultural dimensions. The vigorous Ming founder identified his new regime with three earlier dynasties—Han, Tang, and Song—as great Chinese empires to strengthen its political legitimacy. However, while the Han and the Tang clearly represented Chinese dynastic empires, this was less the case with the Song. The Song dynasty coexisted with several non-Chinese states—Khitan Liao, Tangut Xixia, Jurchen Jin, and later the Mongol-Yuan, with which it exchanged ambassadors and signed peace treaties. In other words, the Song, especially the Southern Song (1127–1276) that lost half of China proper to the Jurchen Jin, was more a dynastic state than a dynastic empire.13 The Song emperors and intellectual elite compensated for the dynasty’s spatial loss by proclaiming their dynasty the cultural center of the world, a proclamation reinforced by a renewed Hua-Yi discourse underlining the ethnic identity of Hua as Han Chinese and the demarcation between China and the non-Chinese world geographically and culturally.

Hongwu identified with the Song, in spite of its territorial limitations, because of the Han-centric Hua-Yi discourse that underpinned both the Song and Ming as Han-Chinese dynasties. In the long period of history from the Han to the mid-Tang, due to the emergence of many non-Han dynasties and the prominent presence of non-Han peoples in China, the Hua-Yi discourse had emphasized culture as the major criterion for differentiating Chinese from non-Chinese. This discourse accommodated the reigns of non-Han rulers who entered China proper and accepted Chinese culture, or became sinicized.14 In the Song dynasty, ethnicity and geography became overriding criteria of the Hua-Yi discourse due to the continuing coexistence of the Song with other non-Chinese states.15 As we will see, Hongwu’s domestic and frontier policies demonstrated that he upheld the Song rhetorical elements of Hua-Yi thought that stressed two important points. First, a Chinese dynastic state’s legitimacy grew out of its role in preserving Han-Chinese institutions and culture. Second, China should be physically demarcated from non-Chinese entities, especially the nomads beyond China’s northern borders. As we shall discuss later, Yongle’s reign, by contrast, witnessed a new interpretation of the Hua-Yi discourse that justified Yongle’s outward-looking foreign policy.

In domestic governance, the Hongwu emperor claimed to restore Han-Chinese culture and institutions that had peaked in the previous Song dynasty. This claim was partly carried out in practice. Indeed, as John Dardess has observed, compared to the Yuan regime that was culturally polyethnic, the Ming was more similar to the Song as a culturally homogeneous regime, in which “the ruling house and the higher political and military echelons shared the same Chinese ethnicity as the majority of the population, and no privileges or concessions were given to non-Chinese languages and culture.”16 Meanwhile, although Hongwu declared that he wanted to undo the Mongol legacy, he in fact adopted many Mongol institutions. Inheriting both the Song and Yuan political legacies, Hongwu fundamentally changed Chinese institutions by formulating sustained principles of imperial autocracy that lasted six centuries through the Ming to the succeeding Qing empires.

To shape the government, society, and culture of the empire into a unified and hierarchical whole, Hongwu employed a system of laws, regulations, and rituals to establish three bulwarks of Ming institutions focusing on the monarchy, the bureaucracy, and the community.17 Later rulers, starting with the Yongle emperor, ignored or significantly altered many elements of the Ming institutions established by Hongwu and, for better or worse, created new dimensions of imperial governance.

Hongwu’s most significant legacy in Ming imperial governance was to create a new type of absolute monarchy, which was a product of the Mongol Empire in its worst era of chaos and brutality. His vision of monarchy was shaped by two “facts” that he believed accounted for the failure of the previous Yuan: Mongol rulers delegated too many duties to powerful ministers, and the Yuan failed to keep society under control due to the laxity (or leniency) of its bureaucratic system. To avoid what he perceived as Yuan weaknesses, Hongwu strove to be, as John Dardess has put it, an autocratic head of state “personally responsible for devising effective means for handling and controlling the world.”18

Hongwu justified his vision of absolute monarchy through establishing a new state ideology. The basis was provided by Neo-Confucianism, which had been the main imperial ideology in China since the Southern Song dynasty, albeit with one significant modification. Neo-Confucianism, as typified by the teaching of such Song scholars as Zhu Xi (1130–1200), advocated self-cultivation, community responsibility, and a politics grounded in a fixed code of morality. While Neo-Confucianists thus offered a distinctive justification for political power and authority, they also believed that moral authority was separate from and transcended the political authority exercised by rulers. Not only did the literati need to cultivate themselves to become sages through Neo-Confucian learning, but the ruler too, as a human being like every other human, needed to cultivate himself through mastery of the Neo-Confucian literary canon.19 Neo-Confucianism thus greatly elevated the role of the literati in imperial politics by making them the moral and political advisors of the ruler. Such explicit tutelage was unacceptable to the Hongwu emperor. He firmly rejected his Neo-Confucian advisors’ proposals to revive the ideal Song political tradition that allowed the literati to govern with, and not just for, the ruler. Instead, Hongwu established what we might think of as a new “imperial Neo-Confucianism,” in which the emperor as sage-king possessed both moral and political authority. In doing so, Hongwu redefined the “partnership,” as Benjamin Elman described it, between the ruler and scholar-officials, making sure that the collaboration between state and literati was on the ruler’s terms.20

In his attempt to justify the concentration of all power in the emperor himself, Hongwu profoundly transformed the character of Chinese government and politics. He controlled the bureaucracy through terror and carried out many bloody political purges against his officials in the 1380s. An initial purge centered on Prime Minister Hu Weiyong (d. 1380), and a string of purges that followed resulted in the deaths of over 40,000 of the latter’s supposed adherents. The Hu Weiyong purge was particularly important in that it led to an imperial decision to permanently abolish the position of prime minister, traditionally the head of the civil bureaucracy. This decision marked a watershed in the history of imperial China. After the abolition of the position of prime minster came the dismantling of three coordinating executive agencies that respectively dealt with administration, military affairs, and impeachment of the bureaucracy and the monarchy. These agencies were all split into smaller units without any unified, overall supervision other than the emperor himself.21

From 1380 onward, the old Chinese imperial power structure, characterized by institutional collaboration between the monarchy and the bureaucracy headed by a prime minister, ended. Henceforward, the emperor took over direct management of the entire administration of the empire, functioning as both its monarch and its chief minister. Although Hongwu worked diligently to be the sole arbiter in government operations, it soon became clear that he alone could not handle the entire burden of governance. He therefore created a new institution that became known as the Grand Secretariat (Neige 內閣) to recruit help among lower-ranking civil officials, whom he used as palace secretaries. These grand secretaries were employed entirely at the whim of the emperor and had none of the executive powers prime ministers had previously enjoyed. Hongwu thus established a new model of autocracy in which the emperor was no longer restrained by any laws or institutions.

Meanwhile, Hongwu enhanced the roles of imperial family members in state governance. In Hongwu’s vision, the empire was the property of the Zhu imperial clan alone, and imperial governance was essentially a family enterprise.22 He created a new imperial state that had origins in both the Chinese and Mongol traditions of familial empire. Chinese traditions in this regard manifested under the Ming in at least three ways. First, seeing the political chaos that the lack of any clear principles of succession had caused under the Yuan, Hongwu returned to the Chinese principle of primogeniture in imperial succession. The majority of later Ming rulers obeyed this principle, allowing the Ming imperial clan to maintain relatively high internal stability. Second, Hongwu revived the ancient feudalistic institution of enfeoffed princedoms, granting his sons freehold estates in order, as Chan has noted, to “invest his sons with substantial power and responsibilities within a familial and dynastic framework.”23 Third, Hongwu promulgated meticulous family laws, completed in 1373 and updated in 1395, known as August Ming Ancestral Injunctions (Huang Ming Zuxun 皇明祖訓).24 While regulating many aspects of the imperial clan’s life, the thirteen-section Ancestral Injunctions functioned as both imperial family and state laws, articulating fundamental state policies that Hongwu expected all his descendants to follow, such as never restoring the position of prime minister.25

The Mongol elements in Hongwu’s design of familial empire were most visible in the influence of a Mongol-style patrimonialism. Hongwu thus appointed the enfeoffed imperial princes to command his main forces stationed along the empire’s frontiers, a policy modeled on the successful Yuan practice of sending hereditary princes to frontier stations as military leaders.26 Among the twenty-four princes Hongwu enfeoffed, the nine princes stationed at the northern borders wielded the most important military power, which helped the ambitious Zhu Di, the Prince of Yan in Beijing, to successfully usurp the throne of his nephew—Emperor Jianwen (r. 1398–1402)—after a four-year civil war.

Zhu Di, becoming the Yongle emperor, inherited some Ming institutions his father created, but changed many others. Above all, he continued his father’s enterprise of establishing ideological orthodoxy, and consolidated imperial Neo-Confucianism through empire-wide education and cultural endeavors. Yongle’s regime published and disseminated three large collections of Neo-Confucian books and commentaries in 1414–15: the Great Collection of Commentaries for the Four Books, the Great Collection for the Five Classics, and the Great Collection on Nature and Principle. The imperial government established this trilogy as the official textbooks that students at all government schools were to use to prepare for the civil service examinations after 1415.27 Through education in a standard school system and the civil service examination system, millions of students over the next five centuries closely studied the three collections and subscribed to the imperial ideology defined by them.

On the familial model of empire-building, Yongle gradually abolished his father’s policy of appointing imperial princes as military commanders and introduced the policy of “restrictions toward princes,” which was followed by all later emperors.28 From then on, Ming princes, though still given princely titles, palatial mansions, and annual stipends for life, had neither political nor military power over their princely kingdoms. They could not even travel without the emperor’s explicit approval. Many of them devoted their lives to patronizing religions or sponsoring cultural projects.29 Yongle and his successors thus completely abandoned Hongwu’s design of making the imperial princes into a military elite responsible for guarding the empire's security. By denying the imperial family members any major military role, Yongle pushed further his father’s centralization of imperial power in the hands of the emperor.

In addition, Yongle initiated the Ming political tradition of allowing forces from the inner court, especially eunuchs, to participate in the exercise of executive power as the emperor’s personal representatives. Yongle, as a usurper himself, trusted neither bureaucratic officials at the outer court nor members of the imperial clan. To consolidate his power, Yongle promoted and relied on two forces from the inner court: a police apparatus for secret investigations, and an army of eunuchs used extensively, as Tsai has noted, for “intelligence gathering, military supervision, diplomatic missions, and the like.”30 Most importantly, he turned to eunuch assistants to manage the flow of documents that demanded imperial attention. Yongle’s choice of eunuch assistance, historians have argued, was “one inevitable makeshift response to the destruction of the leadership in the outer court that had provided rulers in earlier dynasties with responsible executive assistance.”31

Hongwu and Yongle thus planted deep the seeds of the Ming absolutism. Although they framed the autocracy within the Neo-Confucian ideology of sage-kings, they created a new type of relationship between the monarchy and the bureaucracy based on the Mongol imperial tradition that saw officials as mere retainers and servants of the great khan. After their respective efforts to deny the constitutional rights of the civil bureaucracy and the imperial family members to govern with the emperor, imperial governance in principle became the enterprise of the emperor alone. Yet, for this system to work, strong rulers like Hongwu and Yongle were absolutely necessary, and strong rulers were precisely what the Ming Empire usually lacked. Most Ming rulers after Yongle were either weak or eccentric. Although still acting within the institutional framework bequeathed by Hongwu and Yongle, they unintentionally increased the power of both the civil bureaucracy and the eunuchs, and often lost power either to their grand secretaries or to top palace eunuchs.

Yongle’s grandson, Emperor Xuande (r. 1425–35), though still a relatively strong ruler, played a critical role in increasing the power of both scholar-officials and palace eunuchs. He recruited grand secretaries from the prestigious Hanlin Academy and intimately involved them in the empire’s decision-making. He promoted the role of censorate officials responsible for impeaching “wrongdoing” of both the emperor and his officials, and introduced the civilian rule over the military establishments.32 All of these reforms elevated scholar-officials drawn from civil service examinations to the most prominent status in the government. Meanwhile, Xuande created the Inner Palace School in 1426 and appointed Hanlin Academy scholars to teach eunuchs to read and write. Top palace eunuchs now received formal literary education and administrative training. From Xuande’s reign onward, eunuchs established nationwide bureaucratic organs that reached into all aspects of the Ming political, military, and fiscal administration. For instance, after the mid-fifteenth century, eunuchs were regularly stationed in military garrisons as supervisors and functioned as de facto state officials.33

Consequently, a bureaucracy that had traditionally included military officers and civil officials at the outer court shifted to the tripartite forces of civil, military, and eunuch officials at both the outer and inner courts. With scholar-officials and eunuchs being institutionally placed as two sets of imperial advisors, the civil bureaucracy and the eunuch bureaucracy now functioned in tandem to govern the empire. The conflict between the grand secretariat and the eunuchs became an element in basic power struggles to control government decisions after the mid-fifteenth century. When the emperor was weak and the civil bureaucracy was unable to stand up to the manipulations of powerful eunuchs, the court politics was dominated by eunuch dictatorship, a characteristic political ill of the Ming Empire. The two typical examples were the first reign of Emperor Yingzong (r. 1435–49, 1457–64) who blindly trusted the eunuch Wang Zhen, and the reign of Emperor Zhengde (r. 1505–21), who was interested more in entertainment than in affairs of state.

In the sixteenth century, the increasingly bitter struggle between absolute monarchy and civil bureaucracy exacerbated the inadequacies of the Ming autocracy. The civil bureaucracy in the sixteenth century, as Ray Huang eloquently argues, actively sought to constrain the emperor and to dictate his behavior, often in the name of adhering to the ancestral institutions.34 Two constitutional crises that occurred during the reigns of the Jiajing (r. 1521–67) and Wanli (r. 1572–1620) emperors provided the best examples. When Jiajing, who succeeded sonless Emperor Zhengde as the latter’s younger male cousin, insisted on elevating his deceased father to the ranking of emperor, over two hundred officials demonstrated at court. Jiajing responded to his officials’ disapproval by flogging and arresting the demonstrators, among whom seventeen died of abuse and the rest were sent into exile. During the reign of the Wanli emperor, Jiajiang’s grandson, scholar-officials unremittingly opposed the emperor’s choice for crown prince, continuously pressuring Wanli to obey the succession principle of primogeniture. Unlike his violent and aggressive grandfather, the frustrated but equally vengeful Wanli emperor carried on a long-term passive resistance against his bureaucrats. He secluded himself in the palace for almost thirty years, refusing to discuss state affairs, to hold court meetings, or to fill vacant government positions.35

Underlying the fearless or bold actions of Jiajing and Wanli’s officials was a firmly established civil bureaucracy resistant to functioning only as the instrument of absolute monarchy. Yet, while scholar-officials in the sixteenth century used the rhetoric of adhering to ancestral institutions to restrain the power of the emperor, the same rhetoric inhibited the bureaucrats from making any structural changes that would allow them to have constitutionally delegated executive power. Deadlock between the monarchy and the civil bureaucracy continued throughout the late Ming and played an important part in the empire’s eventual fall.

As an absolute ruler seeking total control of his domain, the Hongwu emperor also launched a series of socioeconomic reforms intended to realize his visions of an ideal social order. The goal was to achieve what Sarah Schneewind has described as “a stable, tiered society, minimally managed by a bureaucracy and carefully coordinated with a spiritual hierarchy.”36 The implementation of those reforms was often assisted by strict legal enforcement. While many of Hongwu’s reforms failed, others had long-lasting impacts on Chinese society and economy.37 Only the most significant aspects of the Ming Empire’s social and economic policies will be treated here.

First, Hongwu’s program of “enculturation” largely succeeded in restoring Han-Chinese rituals and social customs. In the name of “using Chinese ways to transform barbarian ways,” Hongwu instructed all his subjects to follow Zhu Xi’s Family Rituals and forbad Chinese to adopt Mongol customs such as using popular Mongol names, dressing in Mongol costumes, or performing Mongol-style greeting and drinking rituals.38 Whoever dared to disobey, even unintentionally, faced harsh legal punishment. For example, according to a placard issued by Hongwu in 1392, any child who shaved his forehead and left a strand after the Mongol custom was to be castrated and his entire family, regardless of social status, was to be sent into military exile at a distant border. The same punishment was to be imposed even on the barber who assisted in the commission of the crime.39 The enforcement of such cruel penalties helped to partially actualize Hongwu’s visions of a revived Han-Chinese culture in people’s daily life. The new dress code established during Hongwu’s reign would become an enduring symbol of Han-Chinese culture for adherents of the Ming dynasty, even after China fell under non-Chinese rule again in the seventeenth century.40

Second, the Ming reinstalled the civil service examination system and used it as a major instrument for regulating social hierarchy and social mobility. Hongwu implemented the civil service examination system in 1384, and Yongle further developed the system during his reign. After 1425, with few exceptions, only jinshi (“presented scholar” 進士) degree holders, who succeeded in all three levels of civil service examinations, were allowed to fill higher civil offices that ranked above 7b in the bureaucracy.41 Unlike the examination systems under the Song and Yuan practices, in addition to the most prestigious jinshi degrees, the Ming created two more state-recognized degrees—licentiates (shengyuan 生員) and provincial graduates (juren 舉人), who respectively passed local and provincial levels of civil service examinations. A licentiate was exempted from labor services and received a stipend from the state, while a provincial graduate was eligible for government appointment at the lowest rank (that of 9b). The Ming state thus accorded to all degree holders or gentry a permanent sociopolitical status superior to commoners, allowing them to play dominant moral and social leadership roles in the local society.42 This social structure was perpetuated in the succeeding Qing dynasty, contributing to the formation of the well-known gentry society in late imperial China.

Third, Hongwu established an official religion that combined a Confucian classical core with state-recognized popular cults and aimed to use divine powers to serve the empire’s governing order. According to Romeyn Taylor, Ming law from the reign of Hongwu mandated that all local officials in prefectures and counties must perform state rites that had been adapted from ancient Confucian texts. Some of these rites were performed at open-air altars for celestial and terrestrial spirits of Wind, Cloud, Thunder and Rain, Soil and Earth, and Mountains and Rivers. Others were performed in official temples and shrines, especially the Temple of Civility (Wenmiao 文廟)—dedicated to Confucius and a pantheon of Confucian scholars and worthies.43 The Ming official religion absorbed many popularly worshipped deities such as the city gods, who, as local administrators in the underworld, were expected to assist and oversee the governance of local officials in this world. Hongwu and his successors also constantly appointed Daoist priests to summon the ferocious powers of divine marshals to enhance the empire’s military powers.44

Last, and also most influentially, Hongwu reformed the empire’s tax collection system. As he only cared about agriculture and gave little thought to markets or commerce, Hongwu established a rural model of static communities for taxation and local control based on an administrative community (lijia 里甲) system. In this system, eleven households composed one jia, and ten jia made up a li. Each jia had one wealthy household (as measured by landholdings and number of adult males) as its chief, and the ten resulting jia chiefs acted in rotation as the community head. These lijia leaders were made wholly responsible for a broad variety of tasks, with tax collection as the principal function.45 The Ming state controlled the lijia communities by collecting detailed information about every household: its household category (civilian, military, artisans, etc.), its members, the number of taxable males, and the land it owned. Such documents, known as the Yellow Registers (Huangce 黃冊), mainly served the governmental purpose of requisitioning labor services and land taxes, the latter being collected chiefly in the form of agricultural products including wheat, rice, and silk.46

The early Ming system of taxation and rural control encountered numerous challenges from the very beginning, including lijia leaders who evaded taxation and labor services, and lijia members who disappeared from the community registers.47 The ultimate problem was the government’s inability to keep land and population records up to date. Although the Yellow Registers were supposed to be updated every ten years, and were indeed compiled twenty-seven times throughout the dynasty, most registers after 1412 simply copied earlier versions, leaving the empire’s textual basis for taxation profoundly divorced from the reality.48 Regardless of several reforms initiated by local governments to solve those problems, the breakdown of the original rural administrative and social institutions became too obvious to ignore in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.49

After the mid-sixteenth century, a rising population (which had reached about 200 million by 1600) and the dramatic expansion of commercialization forced the Ming Empire to seriously adjust its social and economic policies, especially its tax system. Around the 1570s, the Ming government under the chief grand secretary Zhang Juzheng (1525–82) created the Single-Whip method of taxation (its name referring to the braiding of separate strands into one whip). This method fundamentally changed Ming China’s tax system from an agrarian model to a commercial one. The Single-Whip tax system integrated corvée labor obligations with land and poll taxes and commuted the whole into a single tax, levied on land rather than persons and payable in silver rather than rice or other commodities.50 The establishment of this new monetarized model of taxation occurred at a time when the Chinese economy was becoming increasingly integrated into an emerging global economy and the affairs of the Ming Empire became inseparable from world developments.

In establishing the empire’s territorial integrity, the two Ming founders—Hongwu and Yongle—defined the limits of their polity in essentially similar ways. Although neither ruler had any intention of reincorporating the northern steppe controlled by the Mongols into the Ming Empire, both were determined to inherit the former territory of the Chinggisids in several regions that had traditionally not belonged to the Han-Chinese world such as Liaodong, Tibet, and the southwestern borderlands of modern-day Yunnan.

The founding emperor’s words in the Ancestral Injunctions demonstrate the ways in which he approached the empire’s relations with its foreign neighbors, both at its borders and overseas. It reads:

The Four Barbarians are all separated from China by mountains and seas and located at the corners of our territory. Gaining their land is not sufficient to provide us supplies, and gaining their people cannot make them follow our orders. If they overreach themselves to disturb our borders, then they are evil. If they do not constitute a threat to China and we raise armies to invade them, this is not good either. I am afraid that later descendants might rely on China’s wealth and strength and cling to temporary military achievements. Be sure to keep in mind that you should not start wars and kill people without a good reason. However, the northern barbarians have shared borders with China and have engaged in wars with China generation after generation. We must train generals and soldiers to be prepared in advance against them.51

Notably, although Hongyu used the same label—yi (barbarians)—to refer to all non-Chinese, he differentiated between them using two criteria: their geographical distance from China and their historical relations with China. In doing so, he singled out the northern nomads—and the Mongols in particular—from other barbarian peoples due to the continuous threat they posed to Ming borders. For the Ming Empire, the relationship with the Mongols was essentially a matter of frontier management at its critical northern borders, while the relationship with other non-Chinese entities, especially its neighbors in East and Southeast Asia, was a matter of establishing a Sino-centric international order operated through a tributary system. We will focus on the former in this section and the latter in the section that follows.

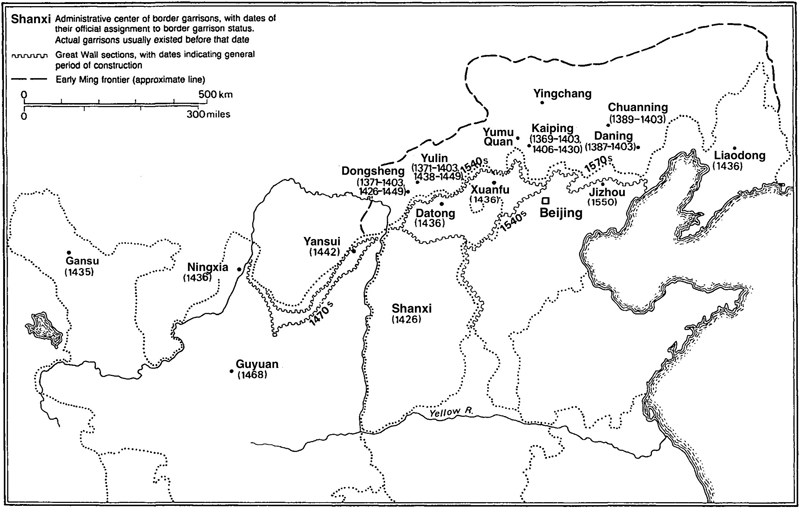

While the Mongol Empire had amalgamated the steppe and China into a single unified empire, the Ming Empire, from the very beginning, chose to separate them. As Zhu Yuanzhang clearly stated in his 1367 proclamation: “Those who claim allegiance to me shall live permanently in peace in the land of Central Brightness, while those who go against me shall remove themselves beyond the frontier fortresses.”52 This command stressed a world bifurcated between China and the steppe along the northern borders marked by frontier fortresses known as sai (塞) in Classical Chinese. The notion of saiwai (塞外), which literarily means lands beyond the frontier fortresses and was used to refer to the nomadic world of the steppe, had existed in Chinese historical reality and cultural imagination long before the Ming.53 For many centuries, Chinese dynasties had seen nomads as “an alien threat to be bought off, walled off, or driven out.”54 Successive dynasties had tried to cut off the steppe from China by building long walls to connect fortresses on the northern borders, but these efforts had never succeeded. The northern borders were more often than not nebulous zones that proved unamenable to sharp demarcation. Through most of Chinese history, these northern frontier fortresses were by no means the equivalent of the Great Wall that most people know today. It was only during the Ming Empire that the Great Wall became a physical marker of the territorial boundary between the Chinese world and the steppe world. Even the Ming, moreover, did not adopt a full-fledged Great Wall strategy until the mid-fifteenth century. Before then, Ming rulers adopted dual strategies of offensive campaigns and defensive fortifications to defend their frontiers (Figure 2.1).

For most of its history, the Ming had the good fortune not to face any unified Mongol polity on its borders. Instead, the Mongol tribes had divided following the expulsion of the Yuan from China in 1368 into the Eastern Mongols (referred to in Ming sources as the Dada 韃靼) led by the Northern Yuan, and the Western Mongols or Oirats (referred to as Wala 瓦剌), and these two confederations were generally at bitter odds with each other. Hongwu and subsequent Ming rulers adopted a strategy of realpolitik in formulating their policies toward these neighbors, based on the changing geopolitics of three key sections in the long northern frontier.55 These three sections corresponded to the northwestern borders of the Ming Empire with the Western Mongols and the polities of Central Asia, the central northern borders of the Empire with the Eastern Mongols on the central Mongolian steppe, and the northeastern borders with Korea and the Jurchen tribes of Manchuria.56

Along the entirety of these northern borders, Hongwu adopted the Mongol-Yuan practice of a hereditary garrison system and stationed the Ming’s main forces in garrisons around Beijing and Nine Command Posts (jiuzhen 九鎮) built along the most strategically crucial frontier areas. These Command Posts, each with a walled city, were guarded by garrisons (weisuo 衛所) made up of professional soldiers from hereditary military households. While the Ming hereditary military household system originated with the Yuan, the method of sustaining the garrison system borrowed from the old Chinese practice of military colonies, which made soldiers grow their own food while they stood ready to serve in the army.57 In addition, although generally hostile to commerce, Hongwu actively mobilized mercantile incentives in the interests of imperial defense. To supplement the economies of these military colonies, Hongwu introduced a salt barter system, which allowed merchants to transport grain, and occasionally other military supplies like horses, to northern defense zones in exchange for government-monopolized salt vouchers. To reduce transportation costs, merchants recruited farmers to migrate to frontier regions and develop commercial colonies, which occupied a significant position in the Ming logistical framework after the Yongle era.58

The focus of the early Ming frontier policy was to deal with the Mongol forces at the central northern borders and the northeastern borders. Early in his reign, Hongwu actively launched a series of military campaigns against the Northern Yuan. Some historians thus argue that Hongwu saw himself as a successor to the Mongol-Yuan Empire and had an ambition of annexing the Mongolian steppe.59 A recent study by Zhao Xianhai, who has made the most thorough investigation of the Great Wall defense systems in the Ming dynasty, demonstrates the opposite: Hongwu did not see the steppe as part of China’s territory.60 Hongwu even openly said to a Mongol ruler of the Northern Yuan, ‘You rule the steppe, and I rule China.”61 He launched the crucial military campaigns against the Mongols in 1372, not in order to occupy the Mongolian steppe but to eliminate the remaining Mongol forces that continued to threaten Ming borders. The failure of the 1372 campaigns presaged the painful reality of continuous conflicts between Ming China and the Northern Yuan regime, which forced Hongwu to change his frontier policy from an all-out offensive to both offensive and defensive strategies. The Ming armies started to build a series of fortresses and passes in strategic regions on the northern borders, establishing a complex of three-layer defense systems.62 Hongwu designed them, as Julia Lovell has correctly argued, to “function not as a fixed frontier but as bases from which to launch further campaigns and influence steppe affairs.”63

While defensive strategies started to dominate Ming frontier management at the central northern borders after the 1372 campaigns, offensive strategies showed positive results at the northeastern borders. The focal point in the northeastern frontiers was Liaodong, which was under the control of a Mongol marshal named Naqaču. From 1368 to the 1380s, Naqaču placed himself in a delicate triangular relationship between the Northern Yuan, Korea, and the Ming. In order to eliminate opportunities for the Northern Yuan to create alliances with Naqaču and Korea, the Ming launched a successful military campaign to conquer Liaodong. With Naqaču’s surrender in July 1387, the Ming established a Regional Military Commission (duzhihuishi si 都指揮使司) in Liaodong, marking a permanent Ming presence in the region.64 The Ming ruled Liaodong through cooperation with the more submissive Uriyangqad Mongols and the Jurchen people, who had control of a large portion of the Inner Mongolian steppe and southern Manchuria. The Hongwu and Yongle emperors created guard units respectively among the Uriyangqad Mongols and the Jurchens, allowing their chieftains to lead their own people and to trade their products for Chinese rice, textiles, and manufactured products with Ming subsidies.65 Meanwhile, the Ming also kept these groups under the close supervision of Ming border offices. In this way, by 1404 the Ming successfully brought the Uriyangqad Mongols and the Jurchen people under loose Ming suzerainty.

The geopolitics of Inner Asia changed dramatically in the early fifteenth century, making the northwestern frontiers the primary source of border crises for the Ming Empire. The rising Timurid Empire at that time united the Western Mongols and was poised to march eastward with the intention of bringing China once more into a consolidated steppe empire. Ming China under the Yongle emperor was spared a destructive war with the Timurid Empire only because their leader, Tīmūr Lang, died in 1405 just before launching an invasion of China.

In response, Yongle launched five punitive military campaigns that penetrated deep into Mongol territory, aiming to degrade the capacity of the Mongols to mount their own offensive against the Ming. Like his father, Yongle did not intend to annex Mongolia, as can be seen from his decision to withdraw garrisons from seven of the eight forts established in the steppe by his father.66

Yongle adopted a new divide-and-rule policy to pacify both the Eastern and Western Mongols. His frontier policy, as summarized by Shi-shan Henry Tsai, followed two basic patterns: the offering of “incentives” that included trade privileges and periodic gifts, and “deterrents” meant to discourage the Mongols’ aggressiveness.67 Yongle mainly used the “deterrents” model to contain the Eastern Mongols and the “incentives” model to buy off the Western Mongols. He thus actively sent embassies to the Western Mongols during his early reign and responded enthusiastically to their first tribute mission in 1408, bestowing seals and princely titles on three Western Mongol leaders. Many Western Mongol tribes at the time were willing to subscribe to the Ming tributary system in exchange for access to the lucrative trade and profitable gifts from the Ming court. This approach was meant not just to keep the northwestern borders relatively peaceful but also to drive a wedge between the Western and Eastern Mongols. Yongle succeeded in gaining the alliance of the Western Mongols in his 1409 campaign to effectively crush the Eastern Mongols. However, after the threat posed by the Eastern Mongols dissipated, Yongle was less willing to offer additional special privileges or to make concessions to the Western Mongols, who responded by waging war on the Ming. As a result, the Eastern Mongols, who had reached a fragile truce with the Ming, capitalized on the weakened state of the Western Mongols and rose again. After Yongle rejected their requests for trading privileges, the Eastern Mongols attacked Ming borders, prompting the last three campaigns of the Yongle emperor against the Mongols in 1422 and 1423.68

For the two decades that followed Yongle’s death in 1424, the Ming in general adopted a less activist foreign policy while continuing to pursue his strategy of divide and rule to deal with the Mongols. This strategy began to lose ground in the 1430s when the Western Mongols decisively defeated their eastern counterparts. In the 1440s, a powerful Western Mongol leader named Esen (d. 1455) compelled the prince of the vital oasis state of Hami (an erstwhile Ming tributary) to accept Western Mongol overlordship, then marched east to overwhelm the Uriyangqad Mongols who had submitted to the Ming. While reuniting the Mongols and establishing his authority over massive territories that stretched between today’s Xinjiang and Korea, Esen also voluntarily took part in the Ming tributary system in order to receive Chinese goods such as tea, textiles and grain to supply his tribal peoples. His large “tribute” missions—an average of 1,000 men per year between 1442 and 1448—put a heavy economic burden on the Ming Empire.69 After the Ming court tried to regulate Esen’s “tribute” missions, Esen responded by attacking Ming China.

In 1449 the Ming Empire had its first, and most serious, collision with the newly unified and hostile steppe power led by Esen. The reigning emperor, Yingzong, whom F. W. Mote characterized as “foolish and incompetent,” followed the advice of the eunuch dictator Wang Zhen to lead a huge army against the Oirat Mongols. The result was the disastrous Tumu Incident, in which the Mongols captured Yingzong alive at the Tumu Fort, approximately fifty miles northwest of Beijing.70 In addition to causing a series of power struggles over succession at the Ming court, the Tumu Incident marked a watershed in the Ming Empire’s northern frontier policy.

A full-fledged defensive policy stressing the wall-building strategy took shape with the ideological support of renewed calls for “defense of the boundaries between Hua and Yi.” The Neo-Confucian scholar-official Qiu Jun (1421–95), a firm proponent of the Hua-Yi discourse, proposed that Ming rulers build extended fortifications to substantially strengthen Ming border defenses. In the decade after the Tumu Incident, the Ming built new fortifications at about fifty important passes while linking the preexisting nine Command Posts and passes along the inner and outer lines of the northern fortresses. The frontier fortresses were now transformed from walls of border defense to walls of border demarcation, bringing the Great Wall into its final shape. Stretching some 1,500 miles from the Jiayu Pass in the far west in Gansu Province to the Shanhai Pass east of Beijing, the Great Wall, for the first and only time, functioned as a physical border separating the Chinese and steppe worlds.

Despite constant raiding and incursions in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, these newly strengthened border defenses combined with the continuing internal dissensions to prevent the Mongols from posing a serious threat to the Ming Empire. The Ming-Mongol conflict remained at a stalemate until the mid-sixteenth century, when tensions at the northern borders escalated again. By 1547, the Eastern Mongols under the leadership of Prince Altan (1507–82) came to control all of southern Mongolia and the strategic Ordos region, and began to raid into Ming territory every year, usually in the spring and early autumn, preceded by requests for trading privileges. The Jiajing emperor, who loathed the Mongols, consistently refused to consider their petitions for trade and insisted on an offensive strategy against the Mongols. Altan responded by besieging the imperial capital of Beijing in September 1550 and mounted increasing raids along the entire northeastern and northern central borders over the next two decades.71

Ming-Mongol tensions at the northern borders eased only when both sides sued for peace after the death of the Jiajing emperor in 1567. In 1571, the Ming signed a peace treaty with Altan’s Eastern Mongols, lifting the ban on border trade and granting Altan investiture as a tributary prince. The Ming eventually adopted the economic-incentive strategy to deal with the persistent Mongol threat, paving the way to relatively peaceful Ming-Mongol relations over the following sixty years. The economic context of the 1571 peace agreement, as Zhao Shiyu has argued, lay not just in the Mongols’ needs of certain products from China but also in the emergence in the sixteenth century of new trade networks that connected the northern borders of the empire to the booming commercial economy of south China. In fact, as will be discussed later, the two most significant frontier issues for the Ming Empire in the sixteenth century, the so-called northern barbarians (beilu 北虜) and the southern Japanese pirates (nanwo 南倭), were inherently connected through the circulation of silver across the borders of the empire.72

In comparison with the turbulent northern borders of the empire, frontier management in the southwest was characterized more by policies of colonization and acculturation. The Ming had annexed Yunnan and Guizhou provinces under the reigns of the Hongwu and Yongle emperors, achieving control over the region initially by force of arms but then through the establishment of provincial administrative offices (in 1382 and 1413, respectively). The new Ming rulers of Yunnan and Guizhou inherited a Yuan institution known as the native administration system (tusi 土司), which offered official titles and other privileges to local hereditary chieftains in exchange for their nominal submission. Yet unlike the Yuan who had left the local native tusi to enjoy a high degree of independence from the state, the Ming were determined from the beginning to assert its control over the southwest. The Ming state therefore actively confiscated territory from the native chieftains in order to set up a new administrative apparatus, organized along Chinese lines and run by state-appointed officials. In order to crush any resistance, the Ming also established more than fifty military garrisons on lands confiscated from the indigenous population.73 Meanwhile, the Ming state encouraged the migration of Han-Chinese settlers into these areas to establish state farms and promote Chinese patterns of land tenure and agricultural techniques. The state also established Confucian schools in these areas to “civilize” local people, particularly the heirs to the native-official posts.74

In their daily administrative practices, however, the Ming officials often took an approach opposite to the overriding rhetoric that stressed the unifying power of the centralizing state and Chinese civilization in transforming non-Han peoples. As Leo Shin has convincingly argued, Ming political and intellectual elites actively practiced ethnic demarcation and categorization to create and perpetuate a set of parameters marking out cultural boundaries between the Han majority and non-Han minorities instead of eliminating such boundaries. In addition to keeping the indigenous population segregated from and unequal to Han-Chinese settlements, Ming officials often reinforced the distinction between the two by categorizing the former as “barbarians” (manyi 蠻夷), who remained outside the state’s formal administrative structure, while the latter were “registered subjects” (min 民), who provided taxes and labor services. Meanwhile, Ming officials sought to differentiate the indigenous non-Han populations further by arbitrarily dividing them into ethnic subcategories according to such criteria as “place of abode, physical appearance, or perceived level of orderliness.” Such practices of demarcation and categorization were strengthened along with the reinforced Hua-Yi discourse after the mid-fifteenth century, as evidenced by Qiu Jun’s proposals that Ming rulers follow the Hongwu emperor’s Ancestral Injunctions to restore clear boundaries between Chinese and non-Chinese.75 The rigidified status boundaries from the mid-Ming onward, as David Faure persuasively demonstrates in the case of the Great Vine Gorge in Guangxi, resulted not in sinicization but in a more robust sense of indigenous identity among the inhabitants of some southwestern borderlands.76

In its western borderlands, the Ming adopted a policy of divide and rule in Tibet by supporting different indigenous political and religious orders. Hongwu also established three Regional Military Commissions, but filled them with former Yuan office holders or indigenous leaders who at least nominally had submitted to the Ming. Unlike the Mongols, who had mainly patronized the Sakya sect of Vajrayana Buddhism and used Sakya lamas as their agents to consolidate Yuan rule in Tibet, Yongle established relations with a variety of other religious leaders in Tibet and granted resounding titles and lavish gifts to lamas who visited his throne. This religious policy, upheld by later Ming rulers, contributed to the thriving tribute missions by Buddhist lamas that characterized Ming-Tibet relations. Scholarly interpretations of such Ming-Tibet relations are highly controversial. Some argue that the Ming had no direct political control over Tibet,77 while others claim that the Ming Empire successfully incorporated Tibet into its territory.78 Those who reject both of these positions tend to contend that the Ming did not bring Tibet under a centralized administration as the Yuan had done, but rather exercised a looser suzerainty over Tibet.79 The latter argument is more convincing when Ming-Tibet relations are considered within the context of the overall history of Ming frontier management. As Shen Weirong has convincingly argued, the Hua-Yi discourse had a profound impact on framing Ming-Tibet relations. On the one hand, the Ming actively sought to control Tibet and to prevent border problems with the Tibetan “western barbarians” (xifan 西藩) through the use of political maneuvers, economic incentives, and military threats. On the other hand, although the Ming court welcomed lama tribute missions and several Ming rulers since Yongle were personally interested in Tibetan Buddhism, the Ming government persistently forbad communications between Chinese and Tibetans.80

In short, the Ming Empire had different goals and strategies for managing its borderlands in different directions. At its northwestern and central northern frontiers, the Ming adopted all three major strategies—offensive campaigns, economic incentives, and construction of defensive works—to secure China proper from the dangerous steppe world controlled by the Eastern and Western Mongols. At its northeastern and western frontiers, the Ming combined military deterrents with political and economic incentives to project varying degrees of influence on the Uriyangqad Mongols, Jurchen tribes, and the Tibetans who acknowledged the Ming supremacy but maintained a considerable degree of autonomy. Only at its southwestern frontiers did the Ming show an assertive posture in bringing non-Han territory in Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangxi provinces within China proper by establishing a regular Chinese administrative apparatus to gradually replace the native administrative system. After the Tumu Incident, the reinforced Hua-Yi discourse that emphasized the demarcation between Chinese and non-Chinese affected Ming frontier policies at almost all of its borderlands. The same notion of strategic demarcation also appeared in the empire’s foreign policy toward overseas states, which was inseparable from the empire’s management of its southeastern coastal frontiers.

Foreign Relations with Other East Asian States

The Ming Empire used political and economic incentives with occasional military action to establish hierarchical suzerain-vassal relations with foreign states to its east and south through a unique tributary trade system. Together with a lasting ban on maritime activities on China’s coast, the tributary system shaped a Sino-centric world order in East Asia that lasted more than 300 years before crumbling in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The Ming was unique among all empires in the history of imperial China for its use of the tributary system to define and regulate all its foreign relations. Again, the two founding emperors were instrumental in creating the Sino-centric world order in East Asia, albeit with very different approaches.

Hongwu established a peaceful foreign policy toward most states underpinned by two fundamental approaches: ritual and economic. Hongwu wrote in the Ancestral Injunctions, for example, that his successors should avoid attacking fifteen foreign states, including four—Korea, Japan, and two Ryukyu states—in East Asia and eleven in Southeast Asia. In 1369, he formalized the relationship between the Ming emperor and the vassal kings of these states in the ‘rituals of vassal kings for paying tributes,” giving vassal kings a nobility rank equivalent to “imperial prince” (qinwang 親王), the highest rank of domestic enfeoffed princes, and bureaucratic rank of 1a, the highest in the early Ming bureaucracy. However, after 1394 Hongwu downgraded all vassal kings’ rank of nobility to the secondary “commandery prince” (junwang 郡王, sons of imperial princes), and their bureaucratic rank to 2a or 2b. The only exceptions were the rulers of Korea and Japan, who were always treated as imperial princes, demonstrating that the Ming strategically treated its two most important East Asian neighbors differently from the others.81

Hongwu also introduced an innovation to ritually integrate some vassal states—especially Korea, Annam, and Champa—into the Ming Empire’s spiritual sphere. In 1369 Hongwu ordered that mountains and rivers within the three states be recorded in the Canon of Sacrifices (sidian 祀典) and included in Ming official sacrifices to spirits of mountains and rivers within the empire’s territory. Then in the next year Hongwu sent envoys to the three states to perform the rites to spirits of mountains and rivers with a sacrificial eulogy allegedly composed by the emperor himself. The Ming envoys installed memorial steles inscribing the eulogy in the three vassal states and erected 148 altars “for the rites of wind and cloud, thunder and rain, and mountains and rivers” in present-day northern Vietnam.82 All these actions were common in Chinese domestic administrative units, but it was unprecedented for them to take place in a non-Chinese vassal state. The steles, altars, and Chinese-style rites unmistakably marked the presence of the Ming government in its vassal states. They also served to symbolically integrate the vassal states into the empire’s official spiritual hierarchy.

Hongwu was enthusiastic about developing and consolidating the tributary relations of the Ming Empire with non-Chinese states and entities. In his thirty-one-year reign, he sent 35 diplomatic missions—the most of any Ming emperor except the Yongle emperor—to seventeen vassal states. He even created a new document system to prevent false tribute missions by checking the authenticity of tallies that had been issued to vassal states. The Ming records documented more than 280 tribute missions from the seventeen vassal states in Hongwu’s reign.83

Yet, from the second half of his reign, Hongwu began to focus on economic approaches in his foreign policy. Turning his attention to the financial burden caused by tribute relations, Hongwu tried to operate the tributary system at the lowest cost by preventing many tribute missions from entering China and bringing all foreign trade under the tributary umbrella. This was a critical reform of Chinese tributary system, because traditionally the system had been separate from foreign trade, especially in the previous Song and Yuan periods.

Hongwu’s tributary trade policy also responded to a new international situation in East Asia that began in the mid-fourteenth century: increasing depredations by the so-called Japanese pirates (wokou 倭寇) that caused many problems in the Chinese coastal areas. Hongwu adopted strategies in both the international and domestic spheres to prevent the maritime troubles from threatening domestic stability. Hongwu diplomatically enticed or intimidated the Japanese government to cooperate in cracking down on the “Japanese pirates.” From 1368, Hongwu continuously sent envoys to Japan, requesting Japan’s submission to the Ming. After Prince Kaneyoshi (1320–83) sent envoys to submit tributes to the Ming in 1371, the Ming recognized the prince and conferred on him the title “King of Japan,” resuming the tributary relation between China and Japan that had been broken off for seven centuries. Ming-Japan relations, however, deteriorated when Hongwu became increasingly suspicious about Japan due to the Japanese envoys’ arrogance and the Japanese government’s hesitation in destroying the Japanese pirates. In 1386 using a fabricated case that charged a Ming military officer with colluding with the Japanese government to assist the former Prime Minister Hu Weiyong to rebel against the emperor, Hongwu definitively cut off the suzerain-vassal relationship with Japan.84

With the diplomatic approach not working well, Hongwu increasingly resolved on a domestic solution by initiating a campaign of maritime prohibition and maritime defense on China’s coastal borders. In 1374 Hongwu ordered the closure of the Maritime Trade Offices in Ningbo, Quanzhou, and Guangzhou, and after 1381 repeatedly ordered a ban on all private overseas trade and forbad people from contacting foreign traders, using foreign commodities, and going overseas. From 1384 the Ming government began to build a series of fortresses and stationed garrison units along the coast in Zhejiang and Fujian provinces.85 As Hiroshi Danjō argues, Hongwu thus established the unique Ming tributary system, which integrated three systems into one: the tributary system, foreign trade, and the maritime prohibition.86

The Yongle emperor took a more expansionist approach to overseas relations. In order to buttress his political legitimacy, Yongle aimed ambitiously to improve China’s image abroad through expensive maritime expeditions, and an increased number of tributary countries. Yongle sent his trusted eunuch Zheng He (1371–1433) and fleets of huge junks—each one over sixty meters long—to the Indian Ocean seven times, reaching as far as eastern Africa. The Ming naval expeditions led by Zheng He, as Edward Dreyer observes, often used military force to resolve local disputes in favor of the Ming, and thus showcased the military might of the Ming Empire.87 Unlike his father, Yongle always treated foreign tributary missions with great largesse and without concern for cost. As a result, many countries rushed to send tribute missions to China after learning how lucrative such missions were. For instance, the number of Siamese tributary missions to China increased from five in the 1390s to more than thirty during the 1420s.88 In East Asia, the newly established Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1897) in Korea entered into a tributary-suzerain relationship with the Ming after 1401, both in name and reality. Also during Yongle’s reign, the Japanese Ashikaga shogunate acknowledged China as its suzerain, and Ming China and Japan resumed the suzerain-vassal relationship.

Yongle took his expansionist foreign policy to a new level when he launched an invasion of Vietnam in 1406 in order to increase Ming influence. Supported by their great economic power and advanced military technology including firearms, the Ming occupied Vietnam for the next twenty years and made the region Ming China’s fourteenth province, Jiaozhi.89 After taking control of the region, the Ming immediately employed methods it had used in its southwestern borderlands: bringing Chinese troops into the region to maintain control, setting up new organs of civil administration under prefectures and counties, and establishing Confucian schools to teach local people Chinese ways. More importantly, as Geoff Wade points out, the Ming also set up three new Maritime Trade Offices in Jiaozhi, indicating “the desires of the Ming to control maritime trade to the south and exploit the economic advantage of such control.”90

Most interestingly, Yongle’s reign witnessed a new interpretation of the Hua-Yi discourse that justified Yongle’s outward-looking foreign policy. According to Hiroshi Danjō, Yongle was the first ruler in Chinese history to state that “Hua and Yi are in one family (Huayi yijia 華夷一家).” This new rhetoric of unity differed sharply from the earlier discourse of Hua-Yi distinction, without essentially contradicting it. As Danjō has argued, the discourse of Hua-Yi unity emphasized not a territorial unification of the Chinese world and non-Chinese world—although Hongwu and Yongle had certainly attempted this in some regions—but a ritual governing order between China and its vassal entities and states through the operation of the tributary system. Meanwhile, at the society level, Chinese and non-Chinese were still geographically and culturally demarcated, which was the focal point of the Hua-Yi distinction discourse. Thus, for example, while expanding state-operated foreign relations and foreign trade, Yongle upheld and consolidated Hongwu’s policy of maritime prohibition.91 In other words, as political entities, Hua and Yi could be unified in a Sino-centric ritual order. But as society and culture, Hua and Yi had to be distinguished and segregated.

Yongle’s discourse concerning Hua-Yi unity casts a new light on his reasons for attempting to bring non-Chinese elements into the imperial court. In his study of the Ming court, for example, David Robinson argues that Yongle used ties with Tibetan Buddhism and various court practices to emphasize that the dynasty had inherited the mantle of the Mongol empire and to enhance the image of Yongle himself as a universal ruler and a successor of Qubilai khan. Other court practices suggestive of this motivation included the introduction of Korean palace women and eunuchs within the Forbidden City, the commissioning of portraits of the Ming emperor on horseback armed with bow and arrow and clothed in Mongolian garb, the enrollment of Mongol and Jurchen warriors into the elite Brocade Guard (Jinyiwei 錦衣衛), and the maintenance of large and varied hunting parks to hold martial spectacles.92 Robinson is right to emphasize that we should understand the Ming court not merely in the context of enduring traditions of Chinese courts but also in the wider stage of contemporary Eurasian courts that inherited aspects of the Mongol legacy, such as the Timurids, the Moguls, and the Ottomans. However, Yongle’s court practices could also be interpreted as his claim to be the universal ruler of All under Heaven, who ritually held the dual identity as the ruler for both Chinese and non-Chinese.

Nevertheless, Yongle’s new interpretation of the Hua-Yi discourse left an important legacy to the Ming tributary system. Seeing himself as the universal ruler of All under Heaven, the combined Chinese and non-Chinese worlds, Yongle redefined the relationship between the Ming emperor and vassal kings as both ruler-subject and father-son or grandfather-son relationships. According to Danjō, the Ming, like earlier Chinese empires, recognized vassal kings through granting investitures, seals, gowns, and caps. Yet, beginning with Yongle’s reign, the Ming uniquely granted specific gowns and caps that were reserved for Ming princes in order to suggest fictive kinship ties between the Ming emperor and vassal kings.93 The tributary system of the Ming Empire thus subtly included a kinship dimension of ritual ties between the Ming and its vassal states.

The wide projection of the Ming power to the rest of world that characterized the Yongle era did not last long. The financial cost became a particularly huge burden on the Ming following an economic downturn in the mid-fifteenth century. Ming China, like much of the rest of Eurasia, experienced serious climatic and agricultural problems that were exacerbated by a sharp contraction in the supply of precious metals.94 When the extreme expense of maritime expeditions and tribute trade exhausted the empire’s treasury, Yongle’s successors after Xuande simply abandoned the maritime expeditions in the name of following Hongwu’s ancestral institutions. Over the rest of its dynastic history, the Ming Empire dominated the East Asian world order mainly through the tributary trade system.

The relationship between Ming China and Chosŏn Korea in the 1500s was an example of the intimate foreign relations that were possible between the Ming and its vassal states within the framework of the tributary trade system. As Seung B. Kye has observed, Korea reinforced its political bonds with Ming when “the Chosŏn elite began to view the Ming emperor as a ritual father as well as the suzerain.” In addition to obligatory tribute missions three times a year, Chosŏn Korea frequently sent voluntary missions in the 1500s, which were welcomed by the Jiajing emperor. Beginning from 1535 and frequently thereafter, the Chosŏn court debated contentiously about whether or not Chosŏn Korea was part of Ming China. This controversy was even submitted to the Ming court for an authoritative interpretation in 1542. Interestingly, the Ming’s answer was “not,” which attested to the above-mentioned reinforced Hua-Yi discourse that emphasized the demarcation between Hua and Yi in the Jiajing era.95 We should not assume, however, that Ming-Chosŏn relations were typical of the Ming Empire’s relations with the rest of East Asia. As Cha Hyewon argues, Chosŏn Korea was unusual in its command of classical Chinese language, its acceptance of and engagement with Confucian culture, and the exceptional degree to which Koreans were willing to observe tributary rites and accept Ming demands in exchange for practical benefits. Ming China and most other tributary states, on the contrary, simply intended to maintain the status quo through the formation of a superficial tributary relationship.96

Indeed, if Ming-Korea relations showcased the success of the Ming Empire’s tributary trade system in establishing a Sino-centered world order in East Asia, Ming-Japan relations in the sixteenth century underscored one of the system’s failures. As the Ming court had limited Japanese trade with China to three tributary ships sent every ten years, there were tremendous financial inducements for the coastal people of both Japan and China to evade state decrees and engage in illegal trade. Governmental attempts to suppress smuggling by force led to armed resistance from a wide range of groups that the state attempted to dismiss as “Japanese pirates,” but which in fact included Japanese samurai, Korean sailors, Portuguese mercenaries, and many Chinese traders and local gentry, all of whom profited from the illicit trade. During the reign of Jiajing, scattered encounters along the coast between the Ming navy and “Japanese pirates” reached their zenith and escalated to become full-scale military campaigns in 1552–59.97