I WAS BORN IN 1952, when the world’s population was 2.6 billion.1 Since then it has almost tripled in size. In 1952 only 30 percent of the world’s people lived in cities, but now more than half do,2 and by the end of the twenty-first century that number will grow to 85 percent. The quality and character of our cities will determine the temperament of human civilization.

In 1952 conditions in many European cities were not unlike those in the developing world today. In one of Europe’s southernmost cities, Palermo, the capital of Sicily, reconstruction after a devastating war was stalled by corruption; lacking affordable housing, families camped in nearby caves while the Mafia built a concrete jungle of suburban sprawl, paving over parks and farms, bribing and threatening local officials with so little regard for building and zoning codes that the result became known as the Sack of Palermo.

To the north, in Germany, 8 million of the 12 million people displaced by war remained refugees, without proper housing or work. To the west, London was shrouded by the “Great Smog,” a lethal fog of sulfurous coal smoke that killed twelve thousand people in the worst air pollution event in London’s history. And to the east, in Prague, the show trial of Rudolf Slánský, accompanied by Stalin’s torture and execution of Jews, and their expulsion from the government, hardened the cold war lines between the Soviets and the West.

The prevailing view at the time was that economic growth was a key solution to the world’s problems. Spurred by the American Marshall Plan, the postwar period in Europe gave rise to the greatest economic expansion in its history, overcoming starvation, providing work and homes for countless refugees, funding social services, and generally improving the quality of life for tens of millions of people. The United States also experienced extraordinary growth. Manufacturing wages tripled from their depression-era lows, America’s middle class expanded, and the populations of many cities rose to new peaks. However, the focus on economic growth alone was not sufficient to generate true well-being.

The 1950s were not a good time for nature. The growth of the world’s cities was fueled by voracious consumption of natural resources: mountains were mined, forests cut, oceans fished, rivers dammed, and groundwater was sucked from the earth—all at a rapidly accelerating pace. There was little thought given to waste. Salinated groundwater, polluted rivers, and stripped topsoil reduced nature’s capacity to regenerate herself, ultimately making the task of feeding and provisioning our cities harder. Although many of the world’s cities grew in the 1950s, the planning for that growth was often shortsighted, ignoring the lessons learned from thousands of years of city-making.

Look at almost any city in the world and you’ll find that the part planned and built in the 1950s is probably its least attractive. Historic plazas became parking lots, rivers were covered and turned into highways, cheap “International Style” office buildings replaced beautifully crafted ones, and vast, efficient, soulless housing estates were built at the city’s suburban edges, disconnected from work, shopping, culture, and community.

Certainly, by the mid-twentieth century, many nineteenth-century neighborhoods needed renewal. In Berlin’s Wilhelmina Ring, thought to be the largest tenement cluster in the world, tiny, teeming apartments were heated by charcoal, and only 15 percent of apartments had both a toilet and a bath or shower. In St. Louis, Missouri, 85,000 families lived in overcrowded, rodent-filled nineteenth-century buildings, many with communal toilets. New York City’s Lower East Side was the most densely populated neighborhood in the world, contributed to significant health and safety issues. These neighborhoods needed regeneration.

After World War I, the dominant approach to the design of urban renewal grew out of the ideas of the Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, known as Le Corbusier. In 1928, Le Corbusier and a group of like-minded colleagues formed the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM), to formalize and disseminate their view of city-making. In 1933 they declared the urban-planning ideal to be the “Functional City,” proposing that urban social issues could be solved by a planning and building design that strictly segregated use according to function. Like Bach, Le Corbusier sought to express the architecture of the universe in his work. “Mathematics,” he wrote, “is the majestic structure conceived by man to grant him comprehension of the universe. It holds the absolute and the infinite, the understandable and the ever elusive.”3 Inspired by Pythagoras’s golden ratio, Le Corbusier proposed it as the ideal basis to determine the proper distances between buildings, and as the ratio between a building’s height and width. The result produced isolated, evenly spaced towers, which were set in unadorned parks.

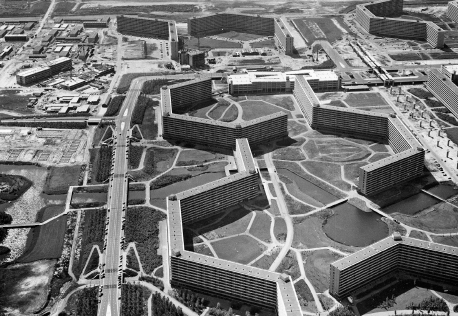

The Functional City approach was adopted all over the world. Historic, messy, vital city neighborhoods filled with dense streets lined with shops and apartment buildings were condemned, torn down, and replaced with Le Corbusier’s “towers in the park,” antiseptic, orderly, tall new apartment buildings with tiny kitchens and bathrooms, separated from one another by green but unusable open spaces. Shops and workshops were limited; these were only places to live. Outside Amsterdam the concept was demonstrated in Bijlmermeer, a complex constructed in the late 1960s of thirty-one ten-story octagonal apartment buildings to house 60,000 people with not a shop to serve them, separated from the city by a wide expanse of parkland.

Bijlmermeer. (Amsterdam City Archives)

The Soviet Union found the Functional City concept particularly appealing, and engaged many of the CIAM architects during the Great Depression. Their ideas were applied at scale after World War II as an inexpensive way to rebuild war-torn cities, and to accelerate Soviet expansion into Eastern Europe. In January 1951, the Moscow party boss Nikita Khrushchev called together a conference on construction, proposing that the people’s housing should be constructed with cheap, prefabricated concrete panels. The next year the Nineteenth Party Congress made the prefabrication of massive housing projects the law of the land, while preserving the option for luxury dachas and government buildings to be handcrafted.

Despite the Soviet Union’s receptivity to their ideas, World War II drove many CIAM members to the United States, where they became deans of the nation’s leading schools of architecture. The principles they taught guided the design of the nation’s urban renewal program. In the 1950s new housing projects like St. Louis’s Pruitt-Igoe, designed by Minoru Yamasaki, won architectural awards for their stark formality. In 1954, Dick Lee, the newly elected mayor of New Haven, Connecticut, adopted the Corbusian model of urban renewal and promised to make New Haven a model city. New Haven’s efforts to replace old neighborhoods with brutally modern architecture received national attention, and won many design awards, but by the late 1960s they had largely failed because they concentrated poverty, isolated residents from services, and limited opportunity for small businesses.

In addition to housing, economic development—the creation of businesses and jobs and the improvement of living standards—is an important element of urban renewal. The prevailing urban economic model of the mid-twentieth century often focused on the development of a few large projects to revitalize a city’s downtown. These deeply subsidized large shopping malls or convention centers often failed because planners didn’t recognize that economic vitality functions at several scales in an overlapping, complex system. The small business—the musical instrument shop, the fabric store, or the corner grocer—is as essential as new housing and grand mixed-use centers. New Haven condemned blocks of older historic buildings to clear and build a downtown shopping mall, which struggled. As the area lost its vitality, its office buildings were only partially occupied and rents dropped. By the end of his term in 1969, Dick Lee said, “If New Haven is a model city, God help America’s cities.”4

In 1970, I arrived in New Haven to attend Yale University. It was an unsettled time. One of the first American cities to industrialize in the late 1700s, New Haven was losing middle-class jobs as manufacturers moved to the nonunion South, or offshore. The Vietnam War was dividing the nation. A persistent recession, rising interest rates, and increasing urban crime were hastening the decline of America’s cities, and in New Haven the murder trial of the Black Panther Bobby Seale exacerbated racial tensions.

The goal of my undergraduate studies was to understand and integrate several big ideas: the nature and workings of the human mind, the functioning of social systems, and the way that the amazing miracle of life evolves toward ever-increasing complexity in the face of entropy and decay. My hypothesis centered on the notion that the same principles that increase the well-being of human and natural systems could also guide the development of happier, healthier cities.

Perhaps the most important ecologist of the twentieth century, the eminent biologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson, was then a Sterling professor at Yale. He graciously agreed to meet with me and discuss these early ideas that grew into this book. In 1931, when he was twenty-eight years old, Hutchinson set off for the Himalayas, to the high Tibetan land of Ladakh, where he studied the ecology of its lakes and its Buddhist culture. Hutchinson was the first to propose the idea of an ecological niche, a zone in which species and their environment intimately co-evolve, nested in ever-larger systems.

When Charles Darwin added the phrase “the survival of the fittest” to his fifth edition of The Origin of Species at the suggestion of the economist Herbert Spenser, by “fittest” he didn’t mean “strongest”; he was referring to those species that fit together best. The magnificent tendency of nature to evolve toward the increasing fitness of its parts lies at the heart of nature’s ability to adapt to changing circumstances. Hutchinson’s concept of ecological niches provided a useful way to think about neighborhoods as nested in the systems of the city, its region, the nation, and the earth. Those that fit best thrive.

Hutchinson was also prescient about climate change; in 1947 he predicted that the carbon dioxide released by human activity would alter the earth’s climate. If this, the planet’s largest system, was threatened, then all the ecosystems nested within it would also be at risk. By the 1950s Hutchinson linked biodiversity loss to climate change. He was also the first natural scientist to explore the intersection of cybernetics (information feedback control systems) and ecology, describing how energy and information flow through ecological systems. Together with the later work of Abel Wolman, who proposed that cities have metabolisms just as natural systems do, Hutchinson provided me with elements that I would eventually integrate into an understanding of cities as complex adaptive systems.

In January 1974 I took off on my own journey to the Himalayas, starting in Istanbul and working my way across Asia as a bus mechanic. In the harsh winter I stood at the gates to the Afghan city of Herat, feeling the extraordinary tidal flow of history. Herat, which had grown to greatness as part of the Persian Empire, was captured by Alexander the Great as his armies swept through to the east, destroyed, and rebuilt as a Greek city. Herat was next conquered by the Seleucids as they expanded out of India to the west, then by Islamic invaders from the east, and so on through history. Standing there, I could feel how the tides of civilizations also contribute to the DNA of our city-making. It also became clear to me that in order to understand cities, I had to learn their histories.

I also set out to understand the larger regions in which they were nested. In the fall I entered graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania to study regional planning with Ian McHarg, who had published a groundbreaking book, Design with Nature. McHarg proposed mapping the natural, social, and historic patterns of a region in layers and then looking at the layers together to see how they affected one another. But what I was yearning for was not yet being taught, a more integrative framework that became known as complexity.

One of the reasons that the world is so volatile and uncertain is that the world’s human and natural systems are deeply complex, and complex systems can amplify volatility. To understand complexity, we should first understand its cousin, complicatedness.

Complicated systems have lots of moving parts, but they are predictable—they function in a linear fashion. And although the inputs and outputs of a complicated system may vary, the system itself is essentially static. For example, think about New York City’s water supply system. Water is collected in upstate reservoirs and, powered by gravity, streams though large aqueducts toward the city. Once the water reaches the city, it flows through thousands of pipes and valves and ends up in the taps of millions of apartments and homes. This system has many elements, but they all function in a linear path from input to output. Essentially, New York City’s water supply system has not changed much over the last 150 years. While the flow of water from the reservoir to a sink will vary depending on the state of the valves along the way, the structure of the system itself is pretty static. Linear systems tend to have very low volatility, and are very predicable.

Complex systems have lots of elements and subsystems that are all interdependent, so that each part influences the others. It is very hard to predict the outcome of an input into complex systems. The interactions of complex systems can amplify or mute inputs. The global economy is a complex system. That’s why in 2011, when Greece threatened to default on half of its $300 billion debt, the global stock markets declined by a trillion dollars, almost seven times the actual amount at risk. Nature is the earth’s most complex system. And perhaps the most complex human-made systems are cities.

Wicked Problems

In 1973, facing a series of intractable planning issues, the University of California, Berkeley, planning professors W. J. Rittel and Melvin Webber published “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.”5 They observed that the scientific rationalism of the 1950s, which proposed that science and engineering could solve all urban problems, hadn’t worked out, and that city residents were resisting everything planners recommended. People were sitting in to halt the urban renewal that was supposed to clear blight, and to stop the construction of urban highways that were supposed to make transportation more efficient. City residents didn’t like new school curriculums, and they didn’t like public housing. Even Minoru Yamasaki’s failed Pruitt-Igoe was demolished in a widely televised series of implosions in 1972. Everything planners tried wasn’t working. What was wrong?

Rittel and Webber’s conclusion was an early contribution to the emerging field of complexity, although they didn’t describe it that way. They characterized problems that science and engineering could solve as tame ones, problems with clearly defined goals and pragmatic solutions. These are called complicated problems in this book. Rittel and Webber observed that the larger issues facing cities had no clear solutions because each intervention improved circumstances for some residents, but made things worse for others. And there was no clear framework for deciding what outcomes were the most equitable, or fair. They concluded that it was almost impossible to balance efficiency and equity. They wrote that the “kinds of problems that planners deal with, societal problems, are inherently different from the problems that scientists and perhaps some classes of engineers deal with. Planning problems are inherently wicked.”

Wicked problems are ill defined and rely on “elusive political judgment.” They can never be solved. Every wicked problem is a symptom of another problem. And every intervention changes the problem and its context.

The unpopularity of city and regional planning in the 1970s emasculated it. Instead of proposing transformational visions, most planners became process managers; implementing the zoning codes that fragmented cities rather than integrating them into a coherent whole. And city planners were also slow to recognize that they were subject to larger forces outside their control.

The World’s Largest Blackout

New Delhi, the capital of India, is among the largest and most populous cities on earth, connected not only to other cities on the Indian subcontinent, like Mumbai and Calcutta, but also to Dubai, London, New York, and Singapore. It is home to superb medical centers, diverse global businesses, a dynamic IT sector, and thriving tourism, all of which have increased its prosperity and created a rapidly growing, well-educated middle class.

On Monday, July 31, 2012, India’s northern electrical grid shuddered, staggered under its load, and then collapsed. New Delhi was paralyzed. Traffic jammed; trains, subways, and elevators froze in place; airports shut down; water could not be pumped; and factories seized up. An estimated 670 million people lost power, approximately 10 percent of the world’s total population. The most obvious cause was that demand for electric power outstripped supply; New Delhi has a hot, humid climate, and as it has become more prosperous more of its people expect to live and work in air-conditioned spaces, creating huge spikes in demand during summer months. But the underlying causes are more complex and intertwined.

The world’s climate is changing, generating extreme weather, including the kinds of record-breaking temperatures that drove up New Delhi’s use of power-hungry air-conditioning. Climate change has also led to shorter and later monsoon rains, reducing the flow of water through hydropower plants, cutting their electrical output. India’s increasingly large and prosperous population is also driving up the nation’s demand for food, and for the energy needed to produce it. In the 1970s, India’s farmers switched from locally adapted seeds to modern “green revolution” hybrids, which required much more water to grow. Faced with less rainfall, farmers turned to electrical pumps to lift deep groundwater to irrigate their crops. As demand for water increased, the water table dropped, requiring more and more energy to pump it from deeper and deeper wells.

India’s overtaxed energy infrastructure lacks the sophisticated software and controls to balance supply and demand. To make matters worse, 27 percent of India’s electricity supply is lost in transmission or stolen. Instead of reducing its energy needs with smart systems, conservation, and efficiency, India is increasing its supply, becoming the world’s largest builder of coal-fired power plants. It’s a pact with the devil, as burning coal only accelerates the climate change already threatening so many of India’s systems. Pollution colors the air in many Indian cities a sickly yellow. On a recent visit to New Delhi I never saw the sun break through the thick, grayish yellow air that engulfed the city.

India also lacks the responsive governance needed to handle the complexity of its growth. The mismatch between supply and demand on that fateful Monday in New Delhi had been predicted. The system was sophisticated enough to track the flow of power and predict a dangerous shortfall, but it lacked the management culture to effectively act on the information. District governors were directed to reduce their districts’ use of electricity for the sake of the whole system, but they did not. Instead, many governors instructed their managers to suck even more power from the grid.

That response reflects a larger general issue faced by all city leaders: the temptation to maximize benefit for an individual district, department, or company versus optimizing the whole system. From an evolutionary point of view an individual might do better in the short term by maximizing its own gains, but over the long run it will benefit more by contributing to the success of the larger system. Since the founding of the very first cities, governance and culture have been used to balance “me” and “we.” Governance provides the protection, structure, regulations, roles, and responsibilities necessary to allocate resources and maintain coherence among a large and often diverse population. Culture provides society with an operating system informed by the collective memory of its most effective strategies, guided by a morality that speaks for the whole. Healthy cities must have both strong, adaptable governance and a culture of collective responsibility and compassion.

Global Megatrends

New Delhi’s issues were exacerbated by climate change, one of many global megatrends that all cities must contend with. These also include globalization, increased cyberconnectivity, urbanization, population growth, income inequality, increasing consumption, natural resource depletion, loss of biodiversity, a rise in migration of displaced peoples, and an increase in terrorism. These and many other megatrends are all known unknowns. We know that they are coming, but we can’t precisely predict their impacts.

Climate change will hit cities especially hard. By the end of the twenty-first century, significant portions of low-lying cities such as Tokyo, New Orleans, and Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, are likely to be underwater unless they invest a great deal of money to build and maintain dikes. Coastal cities such as New York, Boston, Tampa, and Shenzhen face huge infrastructure costs to protect themselves from the rising seas. Inland cities located next to rivers or in the path of upland watersheds will also suffer increased flooding, and cities located at the fertile junction of river and sea may be hit from both sides. And less physically vulnerable cities will be swamped with refugees displaced by the climate and by conflict.

Megatrends such as climate change pose threats to the security of every nation on earth. In a 2014 report, the U.S. Department of Defense concluded, “Rising global temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, climbing sea levels, and more extreme weather events will intensify the challenges of global instability, hunger, poverty, and conflict. They will likely lead to food and water shortages, pandemic disease, disputes over refugees and resources, and destruction by natural disasters in regions across the globe. In our defense strategy, we refer to climate change as a ‘threat multiplier’ because it has the potential to exacerbate many of the challenges we are dealing with today—from infectious disease to terrorism.”6

The devastating civil war in Syria began with climate change. In 2006, a five-year drought began, the worst in over a century, which was exacerbated by a corrupt water allocation system. Crops failed and more than 1.5 million desperate farmers and herders moved into Syria’s cities. Ignored and unable to move forward with their lives, they became frustrated by the repressive regime. Their protests sparked a civil war. In the ensuing chaos, ISIS and Al-Qaeda seized territory, further fracturing the nation.7, 8 By 2015 hundreds of thousands of Syrians had been killed, and 11 million had become refugees, flooding nearby Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq, as well as Europe. In the summer of 2015, the UN refugee agency proclaimed the Syrian civil war the largest refugee crisis in a generation. Germany, whose negative population growth had produced a shortage of 5 million workers, responded with expedience and moral courage by opening its doors, welcoming millions of refugees. But settling and integrating them will be a very complex task.

In the twenty-first century, many of the world’s growing cities will be trapped in a vicious circle: without enough local natural and energy resources to support themselves, they will become increasingly reliant on vulnerable international supply chains for food and water. Their concentrated populations will also be more susceptible to the epidemic spread of disease, and with global prosperity increasingly dependent on a complex system of linked economies, their economies will be more vulnerable to problems that might begin in another city and cascade through the system. Next time, the kind of global financial crisis we experienced in 2009 may spin out of control. Cyberattacks are also likely to overwhelm the technical and social systems our cities depend on. And all of these conditions will affect cities’ populations unequally.

Perhaps most disturbing of the known unknowns threatening cities is terrorism, because its goal is to undermine humanity’s greatest collective achievement, civilization itself. Today’s terrorists range from religious fanatics to narcotics gang leaders. They are motivated by racism, hatred, fundamentalism, and greed. They are often funded by the developed world’s addictions to oil, diamonds, heroin, and cocaine, and rewarded with rape, pillage, fame, and promises of an exalted (and perhaps eternal) life. This fundamentalist terrorism is the antithesis of the morality with which the Axial Age thinkers infused civilization 2,500 years ago. The antidote to terrorism requires disciplined, multisectoral approaches, but it is essential that we respond by affirming the key elements of civilization—culture, connectivity, coherence, community, and compassion—inspired by a worldview of wholeness. Strong social networks that grow from free and open societies are essential to the resilience of cities under all stresses, but particularly the threat of terrorism. Fighting terrorism requires vigilance, security, and intervention, but its greatest opponent is a society that connects its parts, is committed to mutual aid, and offers opportunity for all. Connectivity, culture, coherence, community, and compassion are the protective factors of civilized cities.

Trust is also a critical element of a city’s ability to respond to such stresses. Trust is built slowly; anxiety and fear propagate much more quickly. Unfortunately, trust has been undermined by growing economic inequality and injustice, as well as by tribal and religious conflicts that rack Africa, the Middle East, and India, along with growing anti-immigrant fervor in Europe and the United States.

All these challenges threaten the future of our cities, and there will be many more perils we cannot anticipate. We are tasked with planning for an uncertain future.

The U.S. military describes this condition as VUCA, an acronym for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. The combination of megatrends and VUCA requires us to think differently. As the world’s population increasingly moves to cities in the decades ahead, we must figure out how to make our urban systems more integrated, resilient, and adaptable, while at the same time learning how to mitigate megatrends. The best solutions are those that accomplish both adaptation and mitigation; actions with the most co-benefits will best serve the entire system. For example, simple strategies such as rigorously insulating all of a city’s buildings will significantly reduce their energy use, and thus their climate impacts, while also bringing down their operating costs, making them more affordable, increasing the comfort of the occupants, and helping the buildings function better should the power go out. This in turn will create many local jobs and reduce the city’s dependence on global energy supplies.

Leverage Points of Change

If we ask how human civilization will thrive in the twenty-first century the answer must be urban. Cities are the nodes of civilization. They are key leverage points for equalizing the landscape of opportunity and enhancing the harmony between humans and nature in a VUCA time.

The systems thinker Donella Meadows wrote in her classic essay on the topic, “Leverage points . . . are places within a complex system (a corporation, an economy, a living body, a city, an ecosystem) where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything.”9 An example of just how effective a small lever can be—if it is applied at the right point—took place in 1995, when the National Parks Service reintroduced thirty-three pairs of wolves into the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Prime prey for gray wolves are elks, whose population had exploded without wolves to keep it in check. Voracious eaters, elks had denuded Yellowstone’s landscape.

Within six years of wolves being reintroduced, Yellowstone’s valleys and hillsides were green with renewed forest, which stabilized soil that had been eroding into river bottoms. Songbirds returned. The populations of bears, eagles, and ravens grew, feasting on elk carrion from wolf kills. Wolves also reduced the coyote population, unleashing the rebound of foxes, hawks, weasels, and badgers. The beaver population grew, and as they built their dams they brought back marshlands, increasing the populations of otters, muskrats, fish, and frogs. Beaver dams slowed rivers and streams, encouraging the growth of stabilizing vegetation, and improving water quality.10

The reintroduction of wolves into the Yellowstone ecosystem restored a key element back into a tightly fit ecology. Their return was a leverage point that nudged countless elements back into healthy equilibrium, restoring the health of the system.

One of the key ways to increase the health of cities is to understand how their systems work, and then focus on their leverage points. In 1988, when Pablo Escobar’s drug cartel was fighting an all-out war with El Cartel del Valle, Time named Medellín, Colombia, the most dangerous city in the world. In 2013 the Urban Land Institute proclaimed Medellín the world’s most innovative city.

What turned the city around? Key leverage points included the federal government’s resolve to protect its citizens from crime by augmenting the city’s security forces. As a result, between 1991 and 2010 Medellín’s homicide rate dropped by 80 percent. At the same time, the city invested in new public libraries, parks, and schools in its barrios, or slum neighborhoods. Previously isolated barrios were connected to downtown with an innovative transportation system of cable cars and escalators that scaled the city’s steep hills where its poorest people lived. The cable cars were integrated with a modern underground metro that connected more prosperous residential, commercial, and shopping centers, making them more accessible to the poor, and thereby increasing access to jobs, education, and shopping. Safe mass transit provided an alternative to cars, reducing pollution and traffic jams.

The City was then ringed with a protective greenbelt, setting a limit against unplanned sprawl and providing land to grow food. The greenbelt transformed El Camino de la Muerte—the Path of Death, where gangs used to hang the bodies of their enemies from trees—into El Camino de la Vida, the Path of Life, a walking trail with spectacular views of the valley.11

By focusing its efforts on these key leverage points, in just twenty years Medellín transformed itself from a city that was barely surviving to one that was thriving. The influx of national security officers restored a natural balance in Medellín, just as introducing wolves did in Yellowstone, allowing a richer, healthier ecosystem to emerge.

New Urbanism: Toward a More Integrated Planning Paradigm

In the late 1980s several urban planners and architects who had grown up in the idealistic ’60s and were familiar with older, more coherent villages, towns, and cities in Europe began to work on a new, more integrated paradigm for planning in the United States. In 1993 they formed a new organization, the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU), which was modeled on CIAM’s Functional City, but rather than tear neighborhoods apart, CNU’s mission was to put them back together, with as much diversity and connectivity as possible.

Today, the principles of CNU have largely displaced the ideals of CIAM. In 1996, one of CNU’s founders, Peter Calthorpe (my brother-in-law), was hired by the HUD secretary Henry Cisneros to create a new planning model for public housing. Under the HOPE 6 program, the federal government began to fund cities to demolish their failed towers-in-the-park housing projects, and replace them with new mixed-income, service-enriched, mixed-use communities. Calthorpe wrote the program’s planning guidelines, which included reducing block sizes, reconnecting streets, and knitting the fabric of communities back together. Ultimately the principles of New Urbanism spread rapidly because they appealed to human nature, and because they were so adaptable to variations of place, culture, and environment.

Urban renewal also began to move toward integration, diversity, and coherence outside the United States. In Holland, the concrete towers of Bijlmermeer had grown to house 100,000 people, primarily poor immigrants from Ghana and Suriname. Shunned by the middle class, by the 1970s Bijlmermeer had become known as the most dangerous neighborhood in Europe. The ideal town had become a slum. Then, in 1992, El Al Flight 1862 crashed into one of Bijlmermeer’s buildings, killing dozens. Holland’s response to the disaster spurred a new wave of thinking about how to rebuild cities.

The towers in the park were demolished and replaced with denser midrise buildings enhanced by private gardens. Spaces were created for shops and small businesses, bringing services to residents as well as providing entrepreneurial immigrants a chance to rise into the middle class. The police provided better security. The metro system was extended to Bijlmermeer, connecting its residents with city opportunities. Bike riders, pedestrians, and drivers who had been carefully separated by different road systems were brought back together, creating livelier streets. And the city invested in better social services and schools. Taken together, these elements turned Bijlmermeer into a community of opportunity; today second-generation immigrants living in Bijlmermeer have the same levels of income and university education as the ethnic Dutch.

The Well-Tempered City

Eager to begin applying the ideas that I had been wrestling with, in 1976, I left planning school to become a real estate developer, focusing on the confluence of environmental and social issues in cities. My role has been to imagine and build solutions by manifesting a community’s vision for its future in land and buildings. Funded by complex public and private financing, my colleagues and I coordinate the work of dozens of consultants, architects, engineers, and contractors to create projects that model the solutions needed to make cities happier, healthier, and more equitable. I have also consulted on planning issues in communities ranging from the South Bronx to São Paulo, and from Nantucket to New Orleans.

This work in cities has been extremely gratifying. I collaborate with colleagues who are smart, effective, and motivated to make the world a better place, and we see people’s lives improved by our work and nature less abused. Our strategy has been to imagine and then develop projects that model a bit of solutions to the issues cities face, and then work to disseminate what we learned. It became clear that there is an eager audience for solutions that are financially viable and help solve social and environmental challenges. We discovered that creating successful models and promoting their lessons widely was a key leverage point. Our projects became early models for the green affordable housing, transit-oriented development, green building, and smart growth movements.

This work is also very difficult. The problems are wicked, the tide of megatrends is moving against our best intentions, and we are not working at a scale that is meeting the challenges of our times. I often read and write late into the night, pondering the issues of cities, how out of sync they are with nature and ourselves, and think about the shifts that could realign them—and I listen to Bach. His music is imbued with wisdom and compassion, yearning and resolution, but most important, a sense of wholeness. It came to me that the concept of temperament that helped Bach create harmony across scales could be a useful guide to composing cities that harmonize humans with each other and nature. After all, harmony lies deep in the DNA of cities; it was part of their purpose from the very first, more then five thousand years ago.

I call this aspiration the well-tempered city. It integrates five qualities of temperament to increase urban adaptability in a way that balances prosperity and well-being with efficiency and equity, ever moving toward wholeness.

The Five Qualities of a Well-Tempered City

The first quality of urban temperament is coherence, which can be seen at work in the temperament used to compose The Well-Tempered Clavier. Just as an equalizing tuning system permitted twenty-four different musical scales to integrate and to influence one another for the first time—so cities need a framework to unify their many disparate programs, departments, and aspirations. For example, we know that the best future for children is shaped by the stability of their families and housing, the quality of their schools, their access to health care, the quality of the food they eat, the absence of environmental toxins, and their connection to nature, yet each of these may fall under the mandate of a separate city agency. Most cities lack an integrated platform to support the growth of every child. Integration is the base of the first benefit of temperament. When a community has a vision, and a plan for how to carry it out, and is able to coherently integrate its disparate elements, then it begins to be well tempered. Coherence is essential for cities to thrive.

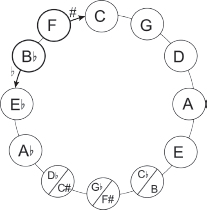

The second quality of the well-tempered city is circularity, which is made possible by coherence. Once notes are tempered, they can be connected. One of Bach’s favorite musical patterns was the circle of fifths, a vehicle that allowed a musical composition to move from scale to scale through its fifth note, the one that fited with the first note of the next scale most naturally, finally ending up back where it began.

The circle of fifths. (Jonathan Rose Companies)

Cities have metabolisms: energy, information, and materials flow through them. One of the best responses to threatening megatrends such as limited natural resources is to develop circular urban metabolisms. Our current city systems are linear; they must become circular, following nature’s way of being.

When the world’s population hits 10 billion in the middle of the twenty-first century, there simply won’t be enough water, food, or natural resources for all of us unless we shift from a linear system, using resources to make things and then discard them, to circular systems based on recycling. As drought-ridden California has discovered, it can purify its wastewater and turn it back into drinking water; it can take organic waste and use it to fertilize crops; it can recycle its soda bottles by turning them into Patagonia vests, creating jobs and resource independence at the same time.

The third quality of temperament, resilience, the ability to bounce forward when stressed, is key to cities’ ability to adapt to the volatility of the twenty-first century. We can increase urban resilience with buildings that consume significantly less energy to be comfortable, and by connecting them with parks, gardens, and natural landscapes that weave nature back into cities. As our urban centers face extremes of heat and cold, deluge and drought, the well-tempered city can use natural infrastructure to moderate its temperature and provide its residents with a refuge from volatility.

The fourth quality of a well-tempered city is community—social networks made of well-tempered people. Humans are social animals: happiness is not just an individual state; it is also collective. This communal temperament arises from pervasive prosperity, security, health, education, social connectivity, collective efficacy, and equitable distribution of these benefits, all of which give rise to a state of well-being. When too many residents of a neighborhood suffer cognitive damage from the stresses of poverty, racism, and trauma, toxins, housing instability, and poor schools, their neighborhoods are less able to deal with the issues of a VUCA age. And it turns out that the health or illth of one neighborhood affects its neighbors in contagious ways. Our well-being is collective.

These first four qualities of temperament reveal how intertwined the world is. Just as the notes of a piano are nothing more than sounds when played separately but come alive when composed in patterns, so atoms and molecules are inert on their own but give rise to life when they are coherently related. Cities also emerge from the interdependence of related parts.

Nature naturally relates—humans must choose how they will relate. The fifth quality of the well-tempered city, compassion, is essential for a city to have a healthy balance between individual and collective well-being. The writer Paul Hawken notes that when an ecological community is disturbed by an avalanche or forest fire, it always heals. Human societies do not always restore their communities after stress. A key condition for restoration is compassion, which provides the connective tissue between the me and the we, and leads us to care for something larger than ourselves. Caring for others is the gateway to wholeness for ourselves and for the society of which we are part.

Donella Meadows observed, “The least obvious part of a system, its function or purpose, is often the most crucial determinant of a system’s behavior.”12 For a city to truly fulfill its potential, all those within it must share a common altruistic purpose, the betterment of the whole in which they live.

At the physical level, the well-tempered city increases its resilience by integrating urban technology and nature. At the operational level it increases its resilience by developing rapidly adapting systems that co-evolve in dynamic balance with megatrends, preserving the well-being of both the human and natural systems. And at the spiritual level, temperament integrates our quest for a purpose with the aspiration for wholeness.

The Well-Tempered City in Action

The well-tempered city is not just a dream. Many of the aspects of temperament we will discuss in this book are already at work in the world today. Our current best practices in the planning, design, engineering, economics, social science, and governance of cities are moving us closer to increasing urban well-being. Even if these actions have only a modest effect when taken alone, their power emerges when they are integrated. Together they provide a pathway through resource constraints, population growth, climate change, inequality, migrations, and other threatening megatrends. Well-tempered cities will be refuges from volatility. If the United States, the world’s largest economy, were to make investments in infrastructure, integrated operating systems, natural systems restoration, and the landscape of opportunity to temper all of its metropolitan regions, it would be an important stabilizing center of gravity in a volatile world.

Imagine a city with Singapore’s social housing, Finland’s public education, Austin’s smart grid, the biking culture of Copenhagen, the urban food production of Hanoi, Florence’s Tuscan regional food system, Seattle’s access to nature, New York City’s arts and culture, Hong Kong’s subway system, Curitiba’s bus rapid transit system, Paris’s bike-share program, London’s congestion pricing, San Francisco’s recycling system, Philadelphia’s green storm-water program, Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon River restoration project, Windhoek’s wastewater recycling system, Rotterdam’s approach to living with rising seas, Tokyo’s health outcomes, the happiness of Sydney, the equality of Stockholm, the peacefulness of Reykjavík, the harmonic form of the Forbidden City, the market vitality of Casablanca, the cooperative industrialization of Bologna, the innovation of Medellín, the Universities of Cambridge, the hospitals of Cleveland, and the livability of Vancouver. Each of these aspects of a well-tempered city exists today, and is continually improving. Each evolved in its own place and time, is adaptable and combinable. Put them together as interconnected systems and their metropolitan regions will evolve into happier, more prosperous, regenerative cities.

Bach’s life’s work was a quest to understand the harmony of the universe, to articulate the rules that allow for the expression of that harmony and then to make it manifest. Bach’s music continues to move us centuries after it was written. The well-tempered city aspires to the greatness of Bach, infused with systems that bend the arc of their development toward equality, resilience, adaptability, well-being, and the ever-unfolding harmony between civilization and nature. These goals will never be fully achieved, but our cities will be richer and happier if we aspire to them, and if we infuse our every plan and constructive step with this intention.

In the pages ahead we will explore the development of cities from the beginning of civilization to the present, in order to understand the conditions that gave rise to cities, and the conditions that create the happiest communities. I hope you enjoy the journey.