J HENRY FAIR

J Henry Fair is a photographer and co-founder of the Wolf Conservation Center in South Salem in New York, USA. A self-described environmental activist, his recent work is a large-scale aerial photography project exploring the extreme effects of human and industrial pollution on the planet.

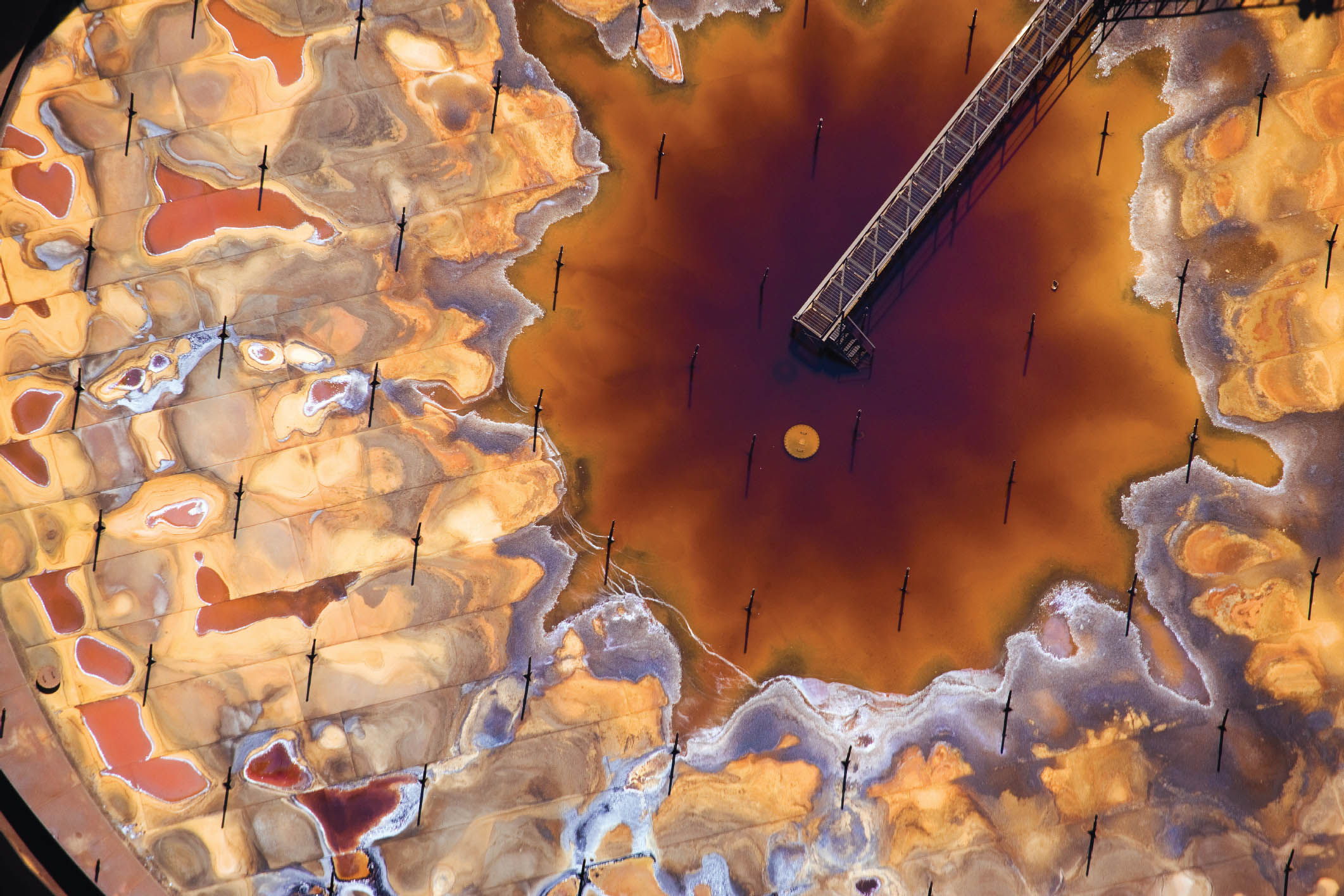

Bauxite waste from aluminium production in Burnside, Louisiana, USA. The red waste is iron oxide, the white waste is aluminium oxide and sodium bicarbonate. Tremendous amounts of caustic (pH 13) ‘red mud’ bauxite waste is produced in aluminium refining, which also generates other contaminants and heavy metals.

I’m from Charleston, South Carolina, USA, but work out of Berlin and New York, making photographs that are simultaneously art, reportage and activism, the ultimate purpose of which is to explain the science behind complex environmental issues.

After stealing an old Kodak Retina camera from my father when I was eleven years old, I immediately knew that photography was my field. Getting a job in a professional camera store propelled me and gave me access to a higher level of equipment, knowledge and technique. I’ve always photographed people and the things that they are affected by and have always had a consciousness about nature, our connectedness to it and the damage we are doing to the planet.

Arriving in New York City at the age of eighteen, determined to be a photographer, sounds romantic. But the execution can be bumpy. Carpentry paid the bills as I started to pick up some photo work. I photographed anything for a dollar, from making eight-by-ten transparencies of an original painting by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, one of the inventors of photography; to doing portfolio shoots for a fly-by-night modelling agency. I have photographed everything from priceless jewellery to religious tchotchkes, catalogue fashion to opera divas. It seemed that doing commercial photography – fashion, portraits, still life – could segue into doing something more personal that mattered to me.

A waste pit at a herbicide manufacturing plant in Luling, Louisiana, USA. The world’s most widely used herbicide, glyphosate, can be used in conjunction with seeds that have been genetically modified to tolerate its application, but is increasingly applied on non-GM plants, including just before harvest. In August 2018 a court in San Francisco found that glyphosate manufacturer Monsanto, was liable for the cancer of a California school groundskeeper and ordered it to pay the man US$289,000,000.

‘What we see in these pictures are the hidden costs of mining; the detritus from the production processes that make the things that we buy every day, whether it’s electricity, bread or the soda cans we throw away on the street. We are complicit, but it’s a complicity of ignorance.’

My enduring fascination with industry and decay led me to photograph ruins, old machines and toxic sites throughout the eighties and early nineties, as I looked for a way to tell a story about the environment. I started to sneak into refineries to make pictures of the inner workings, hoping to highlight the disastrous effect of hydrocarbons on our bodies and the environment. This was before the climate crisis was a worldwide news item and before 9/11, so the level of paranoia in the United States was not so high.

When asked by a press agent some years ago if I saw myself as an artist or activist, my response was: both. He assured me that I would be punished in the art world for that. But my dictum is: art that is beautiful but not meaningful is decoration. Art that is meaningful without beauty is pedantic. A photograph that makes somebody feel has transcended into art. A photograph to which the viewer thinks, ‘Oh yes, cut-down trees on a hillside – seen it before’, is just a document. Intrinsically I understood that I needed to make art for people to feel my sense of urgency.

I want my photographs to work on multiple layers. They must be beautiful and the irony of making something beautiful out of something terrible comments on the irony of life in the modern world, where each of us, no matter how conscientious, must realize that we’re stealing from our grandchildren by not living a sustainable life. The constant study of art teaches me how the old masters stimulated the emotions of the viewer through lighting, composition and colour. That, for me, is the hallmark of really good art: it manipulates our senses to make us feel something.

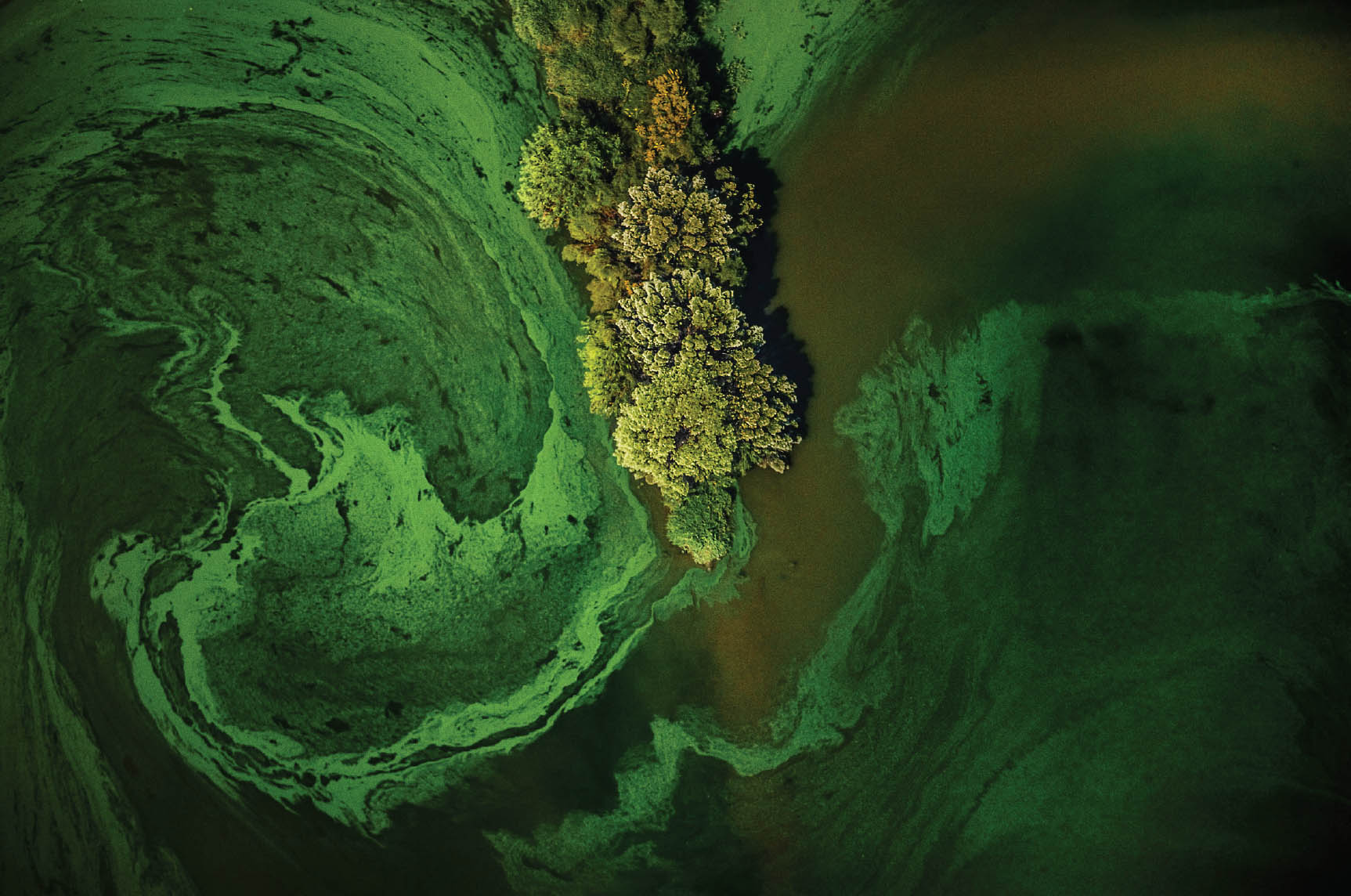

Waste from phosphate fertilizer production in Huelva, Spain. The phosphorous component of fertilizer used in industrial agriculture is obtained from the refining of phosphate rock, which contains traces of naturally occurring radioactive material which are concentrated during the treatment of the crushed rock with sulfuric acid. The waste, shown here, is both radioactive and very acidic.

*

One day, on a red-eye flight from California to New York, I looked out the window at dawn and saw a serpentine river of fog in a valley, with cooling towers and smoke stacks protruding out of it – and I had a revelation: getting above it could be a way to tell the story I had been trying to tell. Then all that remained were the logistical questions of how to find an aeroplane and where to go to photograph. New Orleans was an obvious answer because of ‘Cancer Alley’, the industrial corridor of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, so-called because of the higher than average cancer rates in these locations. So I went to New Orleans and hired a plane.

Aerial photography allows a lot that can’t happen on the ground. Firstly, it allows me to get rid of the horizon and make an abstract composition, the horizon being one of the defining elements in human perception of any scene. And since most of the things I want to photograph are either far from ‘civilization’, or sequestered behind fences and ‘beauty strips’ [rows of trees planted to hide something from the road], flying lets me get over the fence.

‘Our consumer disposable lifestyle is destroying this very complex natural system on which we depend.’

Flying also allows me to go big distances and look for stuff. A perfect example is the tar sands in the far north of Alberta, Canada; being in a small plane allows you to cover that distance, which you could not do with a drone. Over the years, a network of pilots around the world have become friends and essential collaborators on this aerial photography project. Aside from the support of donating their aircraft and flying time, they bring a wealth of local knowledge and experience to my ‘grand wiki’.

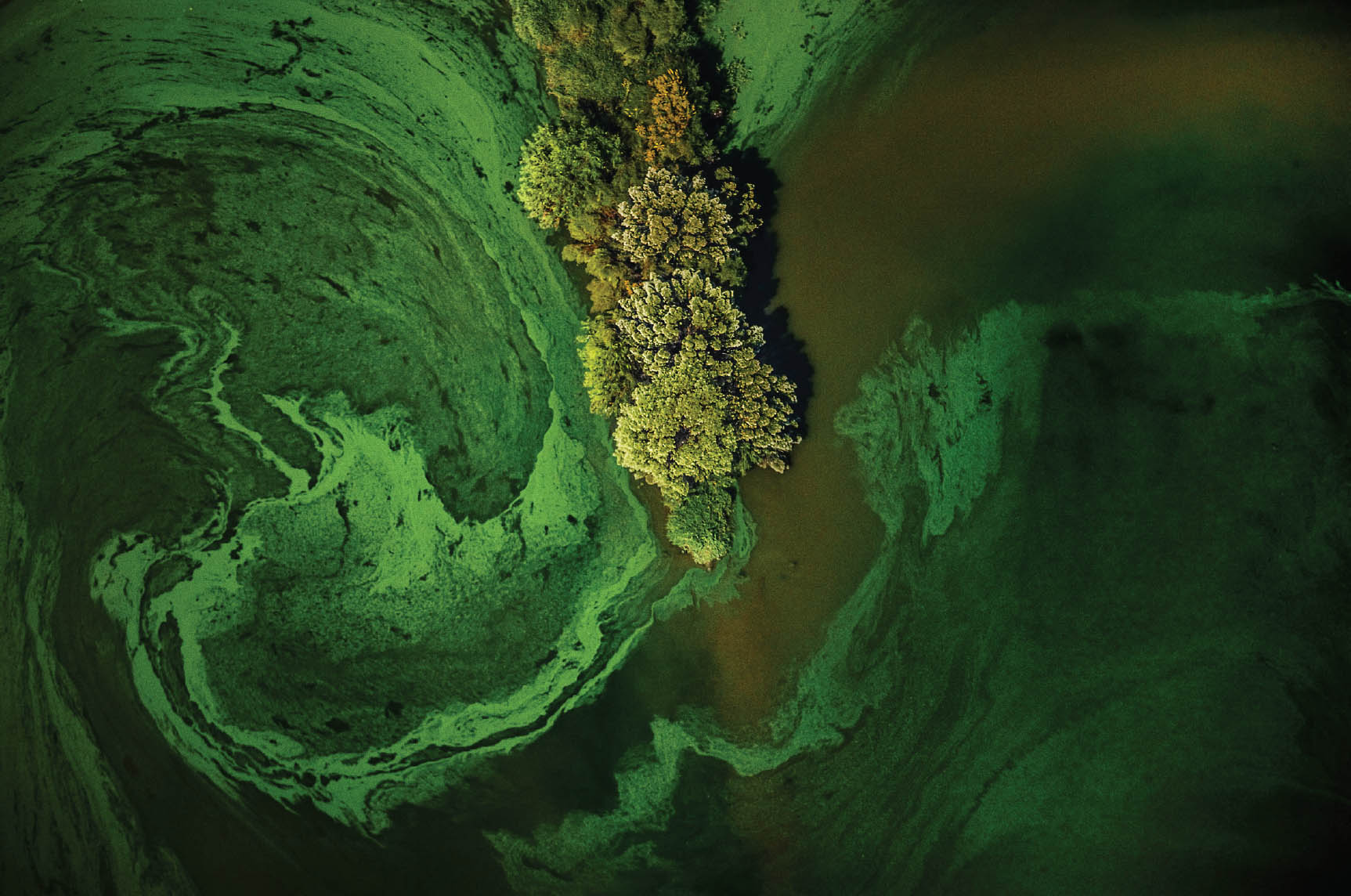

Right after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, my life was in a bit of flux. The day after Christmas I got in a little Cessna, flew up the Mississippi River and started to photograph the industrial sites. Of course, I had no idea what I was looking at, but it was clearly the right place to make toxic pictures. There were giant lakes of green liquid in mountains of white and tremendous impoundments of red ‘mud’ with wonderful flow patterns.

At that point, the environment was not the issue of the day. So back in New York, when I showed the pictures to editors, the main response was: ‘Hmmm, interesting, but what is it?’ So I went back to Cancer Alley and drove to the places I had photographed and thus began the grand research project: piecing together what was in the pictures, the story they told about our impacts on nature and the pollution of our air and water and how that story fitted into a larger story of industry, politics and finance.

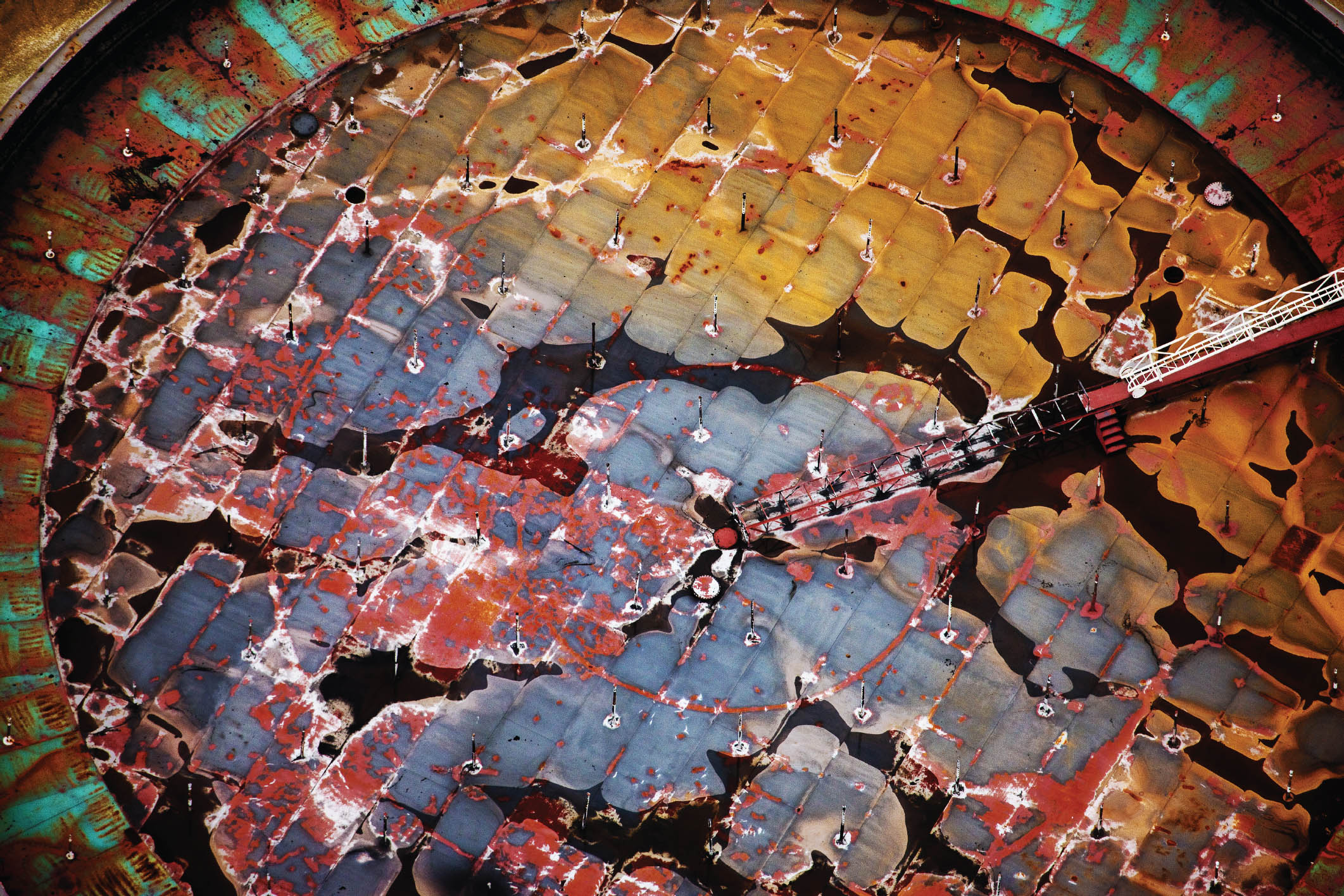

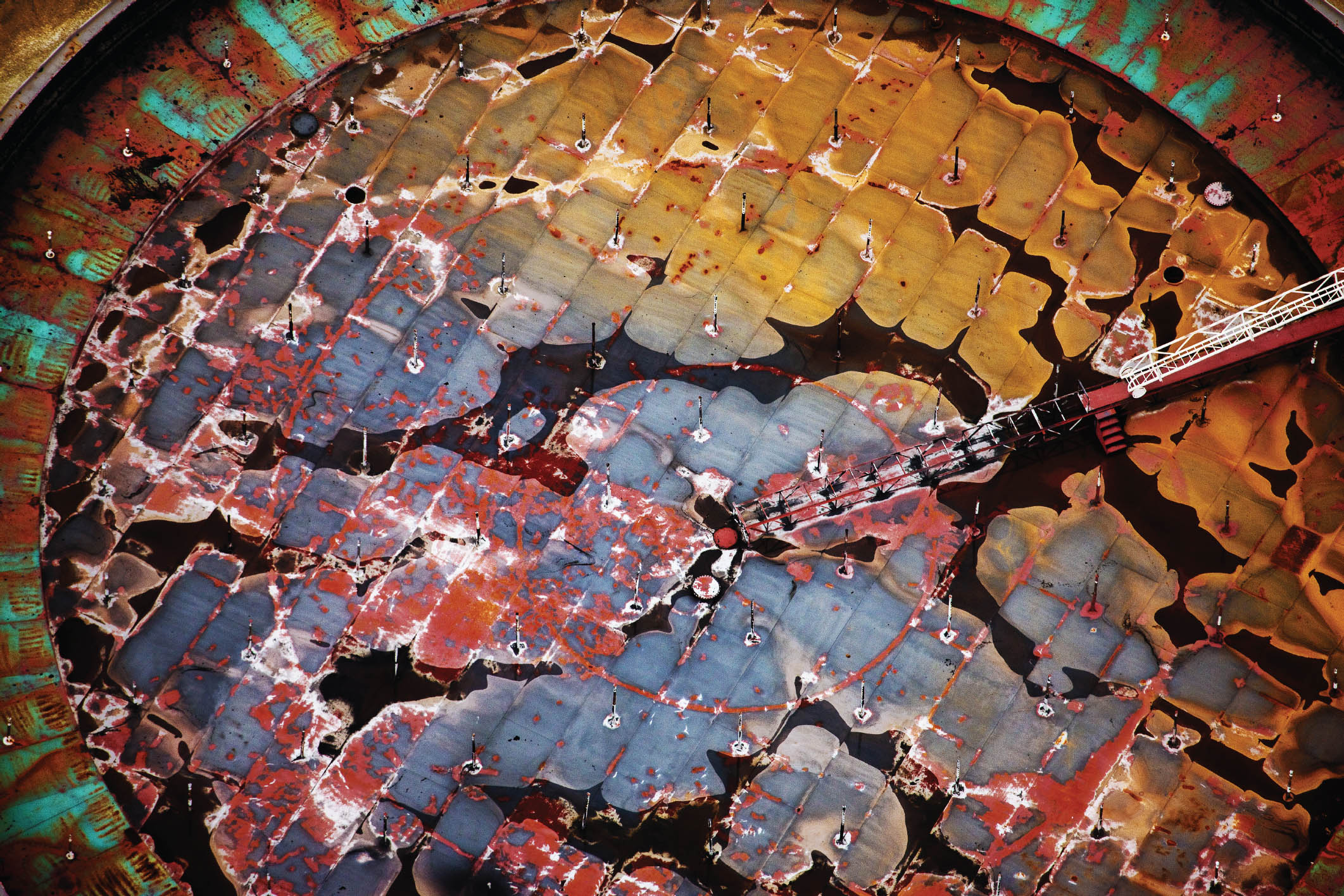

The top of an oil tank at a tar sands refinery in Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada. The tank stores between 400,000 and 500,000 barrels of the world’s dirtiest oil. Tar sands, a layer of bitumen-saturated earth which can be refined into petroleum, are primarily extracted in Canada.

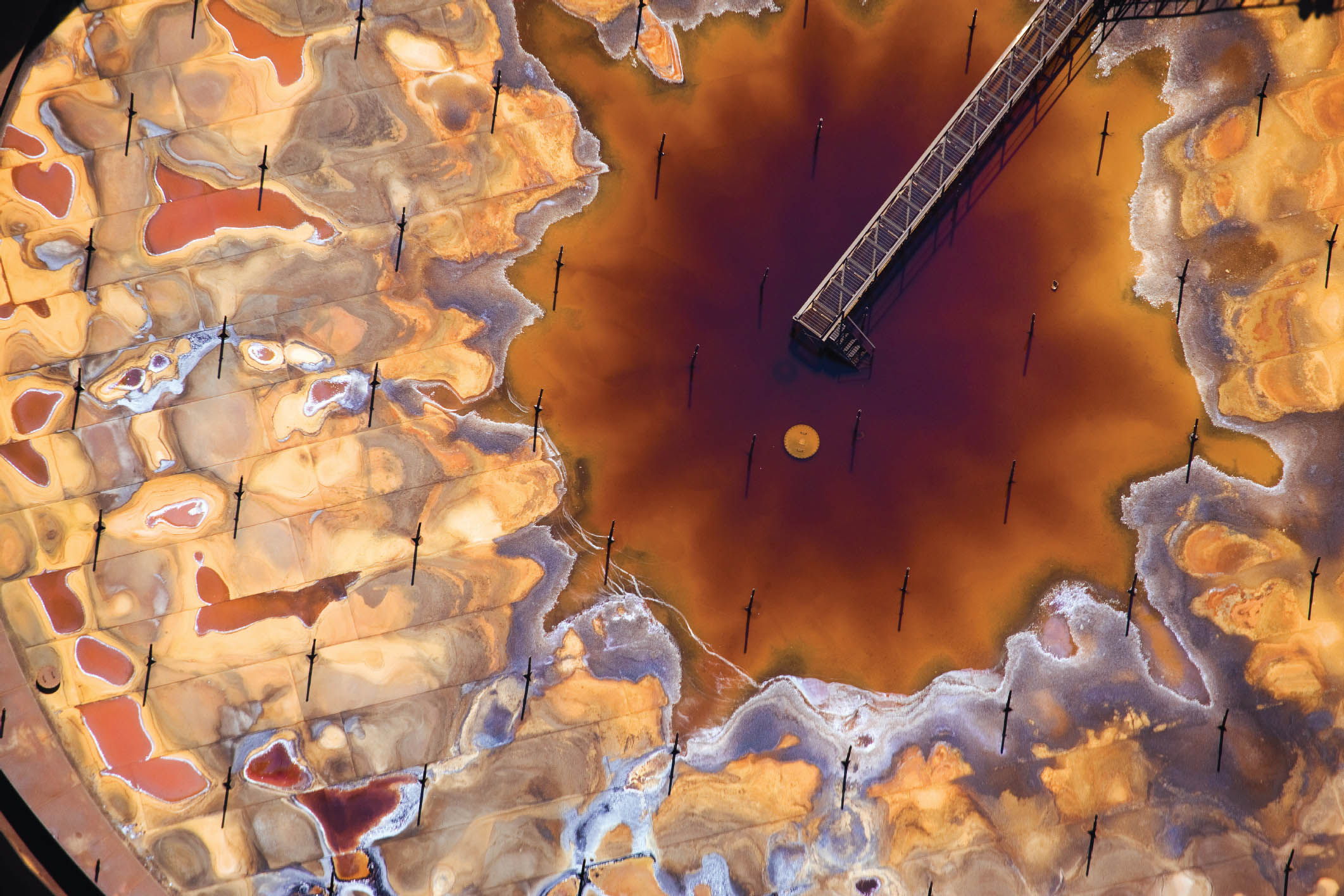

The Rio Tinto Mine in Huelva Province, Spain. Rio Tinto, literally ‘red river’, is one of the oldest and most productive mines in the world, having produced a wealth of different metals over centuries. It is rumoured to have been King Solomon’s mine and the reason that the Moors invaded Spain.

I’m a bit of an engineer at heart and I always want to understand how a process works. So while flying over an industrial facility, I want to take several kinds of pictures; first the ‘art’ pictures – those beautiful abstracts that make people feel something – but I also want the documentary pictures that explain how the process is working. A photo flight around a location entails looking, seeing, understanding and visualizing the shot and then actually making it. The time pressure is immense and the photographic conditions terrible: imagine trying to steady a camera with a big lens while sitting in a small car being shaken by a giant. And the plane is only in the right position for an instant. Having done it so often and developed a good understanding of the processes, I can usually identify a facility and find the essential photographs I want, though sometimes it has taken years to get a particular photo.

Teeth marks from an oscillating excavator in a brown coal mine in Garzweiller, Germany. The process of brown coal mining in Germany is a fascinating study of cruel efficiency; people are forced to move from their homes, which are demolished. The forests are then cut down and the farmland excavated. Coal combustion is the world’s largest source of CO2, as well as the largest source of uranium and mercury released into the environment.

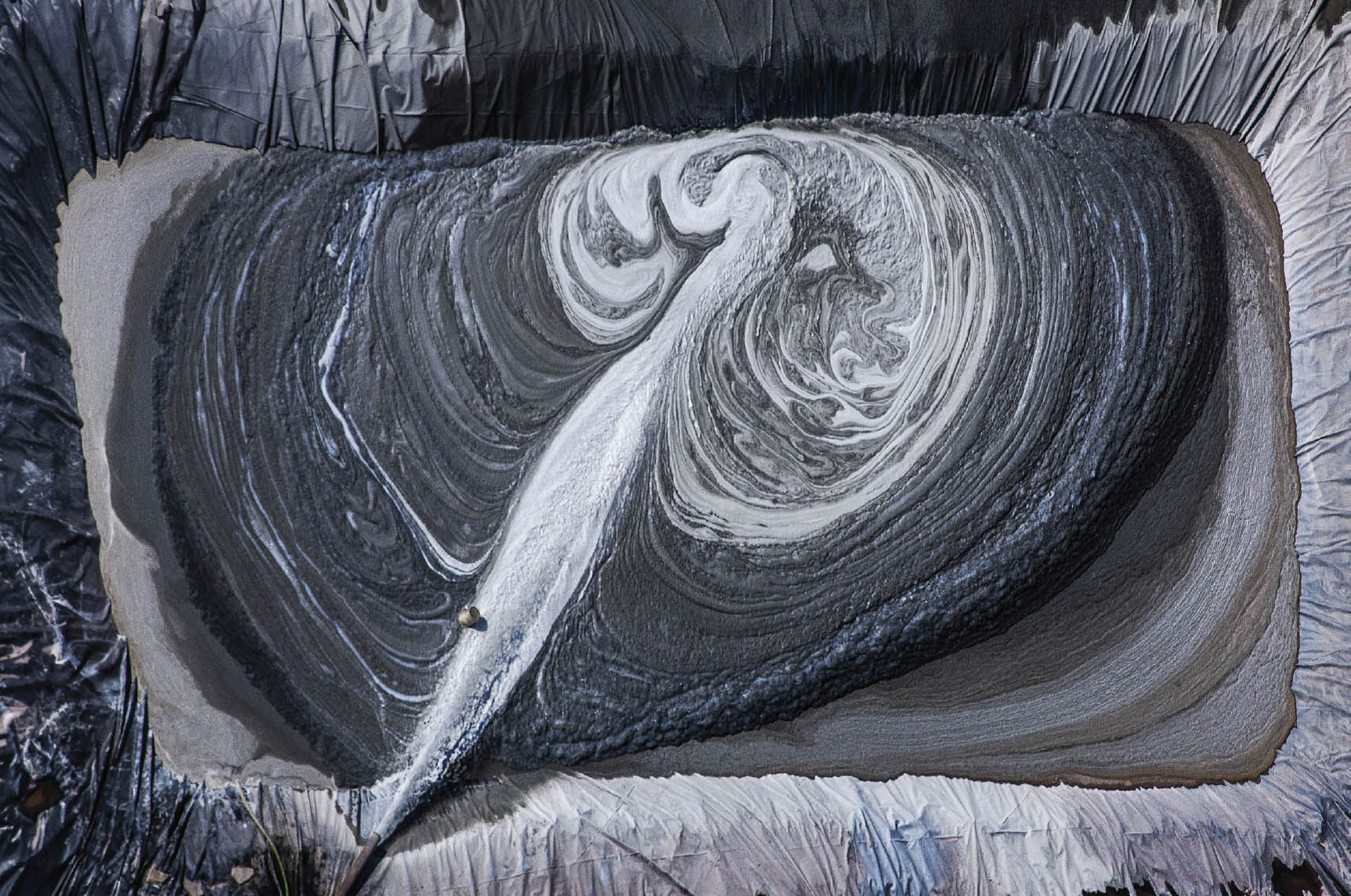

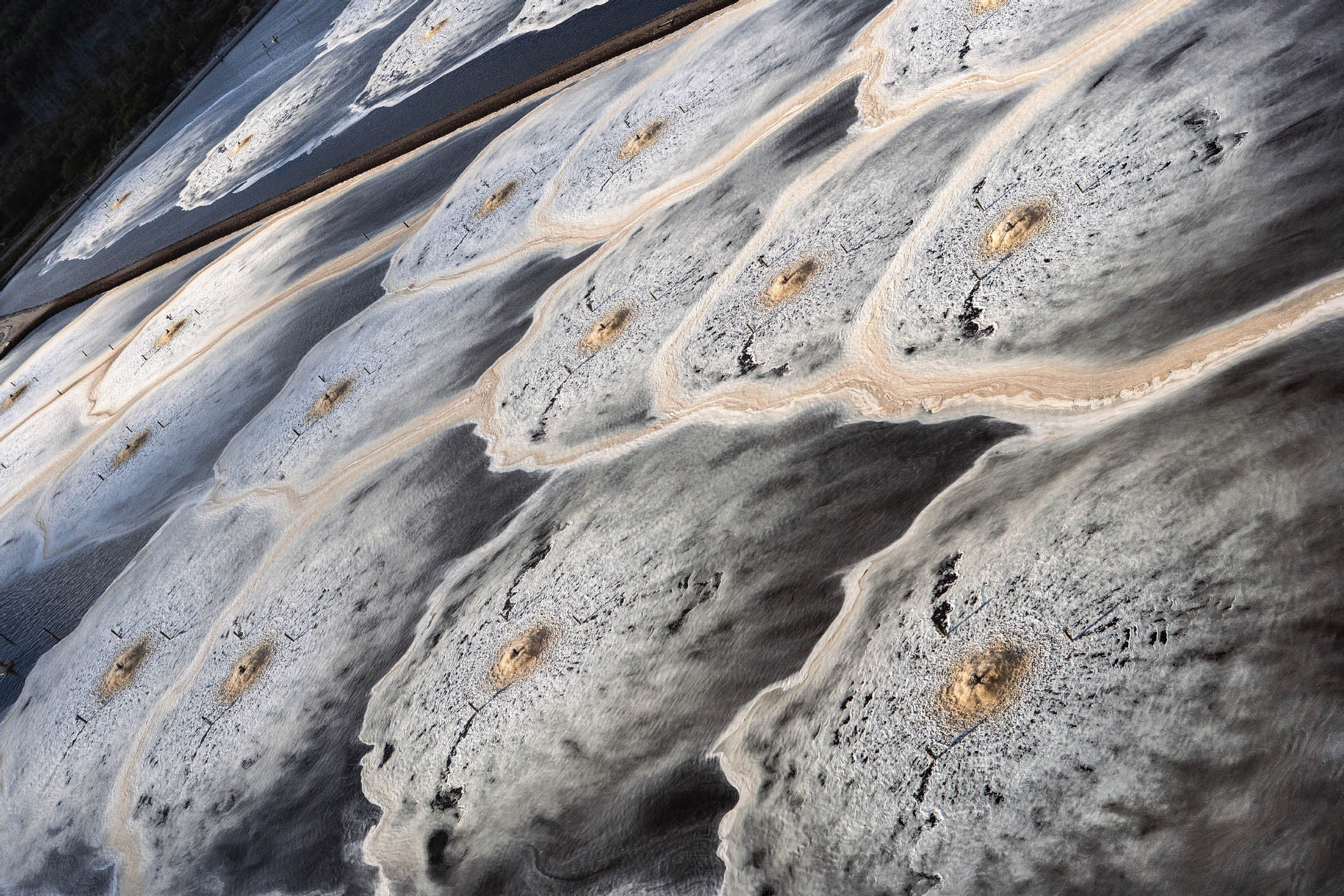

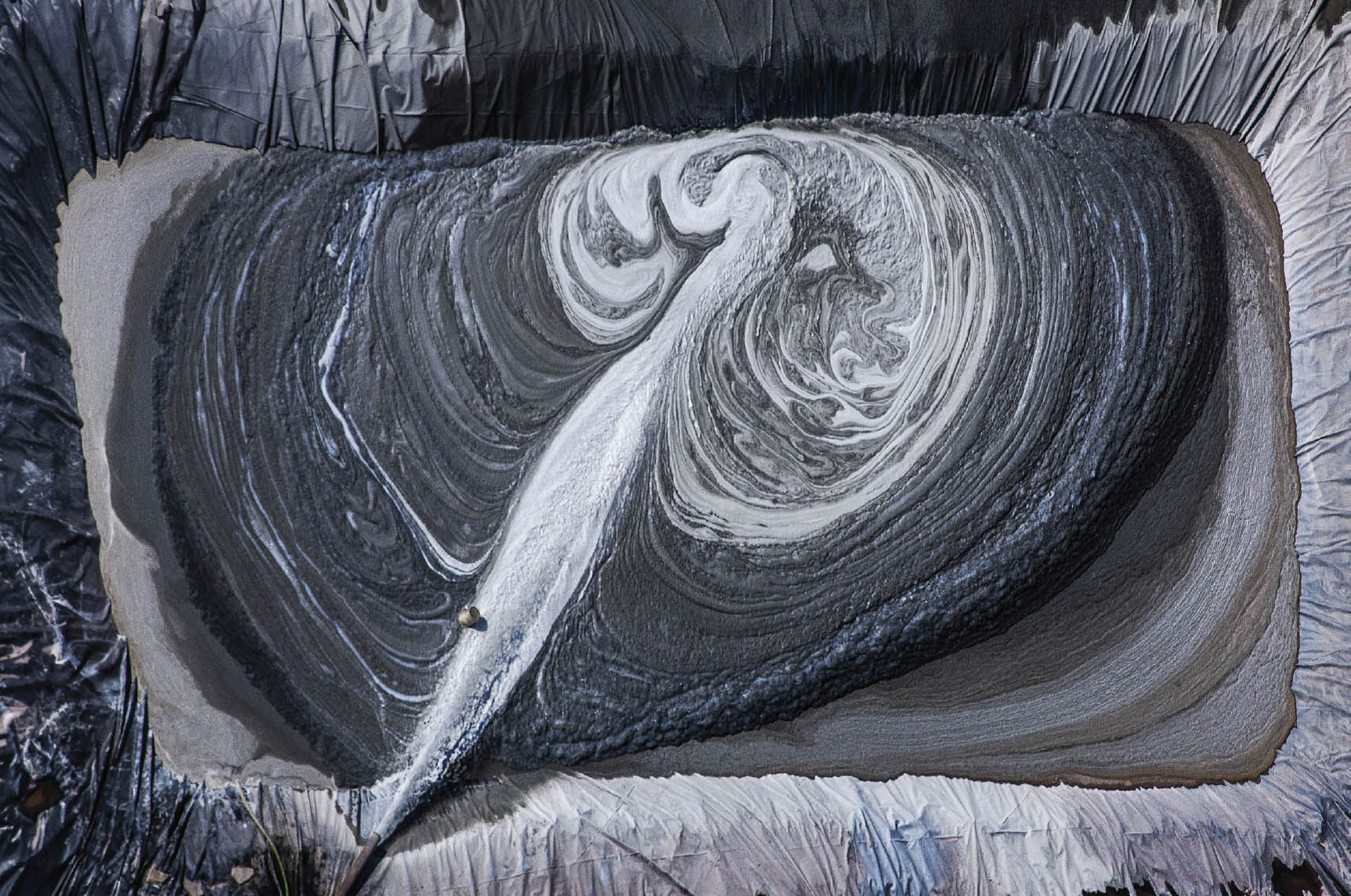

A coal slurry in Kayford Mountain, West Virginia, USA. Mined coal must be washed with water and processed with chemicals to prepare it for market. This creates tremendous volumes of fine, wet slurry which is stored in impoundments held behind earthen dams built across valleys. On numerous occasions these containment structures have failed, releasing large quantities of toxic slurry which have inundated and devastated the valleys below the dams.

A disposal truck pours waste slag from a steel mill into a pit in Huger, South Carolina, USA. This steel ‘mini-mill’ recycles scrap steel into steel beams for the construction industry. Slag consists of unwanted impurities that float to the top of molten metal during the smelting process.

‘Each of us, no matter how conscientious, must realize that we’re stealing from our grandchildren by not living a sustainable life.’

The process of abstraction also took a while to understand; I had to get back on the ground and look at the pictures and think, ‘Ah yes, this one works really well’, precisely because we don’t know what it is. So I started to look for that whilst I was on a mission. I often purposefully include details that can give a clue as to what we are looking at, or at least a sense of the scale.

One of the first places that these disparate elements came together was shooting the Rio Tinto Mine in Spain (p. 70). Legend says that the mine, which is one of the most productive copper and gold mines in the world, belonged to King Solomon. Copper is a low-concentration ore; it’s piled in a giant heap and doused with sulphuric acid. Then from the bottom comes a leachate, liquid that is percolated through the heap that contains the dissolved copper, which must then be extracted. These are complex, often highly toxic, processes; some of them I understand, some not – I should have paid more attention to my high school chemistry teacher. In that particular Rio Tinto shot of the mine, it looks like slurries – meaning liquid with suspended solids – were dumped repeatedly, so we see these fingers dribbling down from a dyke. There are colours that recur, which can be clues for understanding what happened there.

What we see in these pictures are the hidden costs of mining: the detritus from the production processes that make the things that we buy every day, whether it’s electricity, bread or the soda cans we throw away on the street. As an example, making just one single-use aluminium can requires enough electricity to power your computer for three hours. We are complicit, but it’s a complicity of ignorance. We must educate ourselves if we want to make a difference and demand laws dictating that things are made sustainably. Let’s be clear: the companies producing the terrible things that I photograph are usually acting within the law. And often, they have paid the politicians to write the laws for their benefit.

Coal ash waste at an electricity generation plant in Canadys, South Carolina, USA. When coal-fired power plant ash is improperly disposed of, contaminants including arsenic, lead, mercury, selenium and others can migrate into groundwater, lakes and streams. This plant was cited by the US Environmental Protection Agency in 2011 as a ‘proven case’ of environmental damage.

I believe we can create change in three ways: in the voting booth, through the things that we choose to buy and by speaking out.

There’s a forest in Germany called the Hambacher Forst, one of the last ancient forests in the country. Since it’s adjacent to an expanding brown coal mine it’s been progressively cut down over the past twenty years, but still there are thirteen species from the European Red List of threatened species living there. The power stations fed by the coal from this mine (the largest hole in Europe), are the worst polluters and carbon emitters in the European Union. In the summer of 2018, this forest became the centre of a hot political debate in Germany and suddenly, all around Berlin, drawings appeared of chainsaws and the words ‘Hambi bleibt’ [‘Hambach stays’]. We made this a key part of the man and nature ‘Artifacts’ exhibit I did at the Berlin Museum of Natural History that year. I see the role of artists as reflecting and focussing the sentiments of their society.

Germany has very strict laws: tree-cutting has to be done in October. Momentum built and by September of that year, 50,000 Europeans marched into this last remaining bit of woods and said, ‘You don’t cut this forest.’ And what do you know? A court in Cologne stopped the cutting of the forest, which prevented the expansion of the coal mine. Thus, eventually it will starve the power plant. When people stand up and declare their intentions and their wishes, governments quake. Look at the effect of Greta Thunberg and the Extinction Rebellion and FridaysForFuture movements; the derision that’s directed at Thunberg tells us that the powers that be are worried about her and this momentum.

*

A perfect example of the hidden costs is playing out in the giant forest and river system we call the Amazon, one of the great stabilizing forces in the climate patterns of the world – but we are cutting it down to grow cattle and soy for export to supply the world’s demand for cheap beef. The damage is systemic and total: deforestation, habitat destruction – which leads to the extinction of species we haven’t even discovered – the alteration of the world’s moisture patterns, increased methane emissions by the cows themselves, to list but a few. All for a fast food hamburger.

Similarly, if we buy the most common brand of facial tissue, we should know that it means the cutting down of an old-growth forest in Canada, the loss of habitat for all the wildlife there and the release of all that carbon into the atmosphere, both from the trees cut down and from the ground disturbed. And on top of all that, tremendous water depletion and water pollution. All for one facial tissue, which we discard after blowing our noses therein.

‘We can do this, but we need to realize the level of the crisis.’

Aerators agitate waste from the manufacture of facial tissues in Terrace Bay, Ontario, Canada. This aeration pond is part of the effluent treatment system. The primary task of the treatment is to remove organics (wood fibre) from the water before it is returned to its source. Water pollution from paper mills contains toxins such as lead, mercury, chlorine compounds and dioxin.

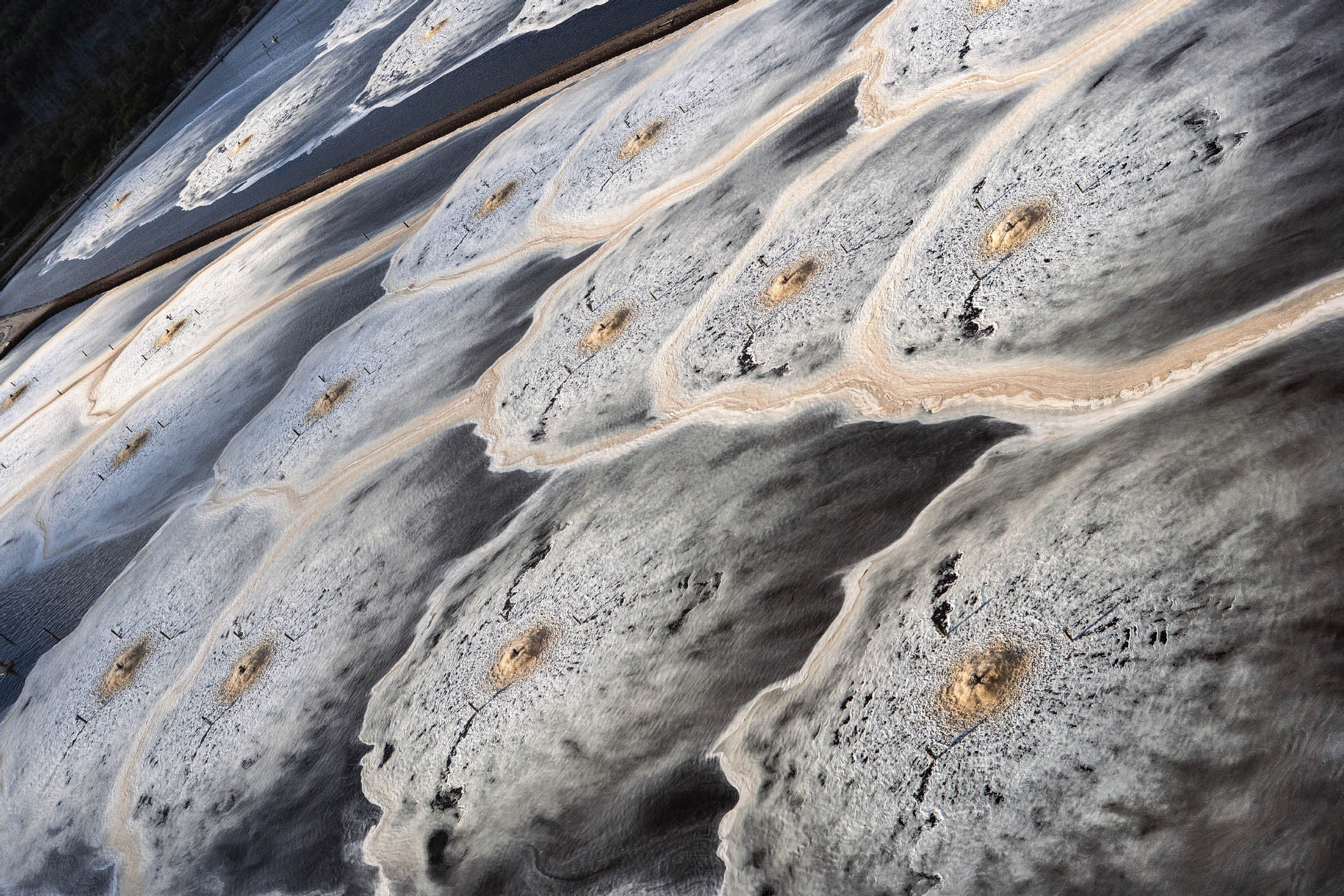

Machine tracks can be seen in bauxite waste in Burnside, Louisiana, USA. At aluminium oxide refineries ‘red mud’ bauxite waste is pumped into vast storage impoundments and allowed to settle. The waste impoundments require grading with heavy equipment to maintain proper drainage for dewatering. Once dry, dust carrying contaminants is blown by the wind, covering everything nearby.

A drilling slurry at a hydro-fracking drill site in Springville, Pennsylvania, USA. ‘Hydro-fracking’ is the high-pressure injection of tremendous volumes of water and chemicals to fracture the subterranean shale rock and release the natural gas trapped there. These drilling muds (the waste pumped out during the boring of the hole) include rock debris, petroleum lubricants, heavy metals and possibly residual radioactive material.

What I’m trying to do is raise awareness, get people to feel and think about the hidden costs of each of these things. And the way to do that, I’ve decided, is by using art – by creating a compelling apparition that prompts a pause, to stop and think – and with a level of irony that causes the viewer to consider their part in all of this. I back up my work with a tremendous amount of research which is then correlated to the pictures, starting with the basic facts: who, what, when, where, why, how – to the more esoteric: what does it mean, how does it relate to the larger stories, both local and global.

*

The bottom line is this: we’re in crisis; our society and economy could all come crashing down and no one wants to talk about it. We are altering the inputs to this incomprehensibly complex planet that has provided us with clean air, clean water, regular rainfall, fish in the ocean – all for free. What a gift! And we are disrupting that system. The most visible disruption at the moment is the climate crisis, caused by changing the balance of CO2 in the system and thus disrupting the weather. In fact, it’s not changing as fast as it could, because the ocean is sucking up all the carbon dioxide (we don’t know why) and becoming more acidic, preventing shellfish from forming their shells and killing the corals. The oceans are going to crash and then they won’t provide anybody with food. A huge number of the world’s population lives off protein from the ocean. How will we feed those people?

A phosphate waste impoundment in Lakeland, Florida, USA. This outlet pipe is at the bottom of a giant ‘gypstac’ phospho-gypsum waste impoundment and creates a stream that eventually reaches the local water table. The weight of these gypstacks is tremendous and there have been instances of the ground underneath the stacks collapsing, allowing tremendous volumes of radioactive, acidic waste to contaminate aquifers.

Continuing to list the very plausible doomsday scenarios only bores, repels or disheartens – and thus demotivates. And in fact, there is plenty of cause for hope: the human spirit, earth system resilience and technology are my sources. I rejoice in stories of fisheries rejuvenating after extraction stops, of the efforts of groups of people to protect their local environment from extraction or pollution and the fact that solar energy is now cheaper than coal.

The message behind my work is: our consumer-disposable lifestyle is destroying this very complex natural system on which we depend. We must stop burning hydrocarbons today. We must change our societal model from consumption and disposal to sustainability. Ultimately that means that every system must be renewable – what you take out has to be replaced.

My belief is that only sustained popular expression of will can drive change. I believe that governments respond to corporations because corporations give governments money, but corporations will respond to their consumers. So, if we, as citizens, demand toilet paper made from post-consumer materials, we will get it. We’ve seen this again and again. When the hybrid car came out, the media laughed at it – but people bought it. I believe people are worried and want to do the right thing to save the environment, but don’t know how. One powerful way is to be cognizant of the impact, the hidden costs, as we make our purchase decisions.

‘I believe we can create change in three ways: in the voting booth, through the things that we choose to buy and by speaking out.’

We live in this bountiful world with all of our modern technology, so complex and interconnected. We have seen how quickly and unexpectedly drastic change can be forced upon us and the interconnectedness of the world means that disruptions spread quickly. None of us wants to go back to the Dark Ages; our world is comfortable and exciting. If we are to preserve this standard of living, we must move quickly to make industry sustainable and we must raise standards of living around the world so that people everywhere feel stable and secure.

Already Europe especially is changing. They are building windmills and solar plants – it’s working. There are plenty of instances of societies making great sacrifices, getting behind a leader and doing what is necessary to save the world. We can do this, but we need to realize the level of the crisis.

The top of an oil storage tank at a refinery in Pascagoula, Mississippi, USA. Burning hydrocarbons has numerous known and unknown effects. Climate change is the result most often in the news, but air pollution and the death and disease it causes are also getting attention. Interestingly, these two pollutants also interact in unpredictable ways: new research shows that the particles in clouds of air pollution are actually slowing the rate of climate change by shading certain areas and reducing heat gain. But the wrong areas are being shaded, specifically the oceans, which is disrupting monsoon rainfall patterns.

A bulldozer pushes petroleum coke, or ‘petcoke’, waste from oil refining in Texas City, Texas, USA. Petroleum coke, a solid more than ninety per cent carbon by-product of the oil refining process, is used as a source of energy and high-grade industrial carbon. Fuel-grade petroleum coke, which is high in carbon dioxide and sulfur, is burned to produce energy used in making cement, lime and other industrial applications.