Operation Hooper began in rather less secrecy than Operation Moduler. Scarcely three weeks before Hooper’s launch day – Saturday 13 December 1987 – the United Nations Security Council unanimously demanded that South Africa withdraw all its military forces from Angola.

South African Foreign Minister Pik Botha reacted to the Security Council’s 25 November resolution by flatly rejecting the demand. ‘South Africa will not be prescribed to in this manner,’ said Botha. ‘The South African government will decide for itself when South African troops will be withdrawn from the current battleground.’

The foreign minister then stipulated the circumstances under which Pretoria would consider ordering the SADF to withdraw from Angola: They would pull out only when Cuban and Soviet troops and military advisers were withdrawn, or when South Africa’s security interests were no longer directly affected by the Soviet and Cuban presence there. [The or was important, in view of the fact that Angola and Namibia had become the focus of one of the most fascinating diplomatic chess games in Africa’s history. In that game the military would be pawns – vitally important pawns, but pawns nevertheless – hogtied in what they could do by the politicians, but continuing to die, eat bully-beef and drink lukewarm contaminated water in the interests of the ‘great game’ while the diplomats sipped good wines and dined well.]

The furore had erupted at the UN before South African Defence Minister Magnus Malan finally admitted, in a statement released in Pretoria in mid-November 1987, that the SADF was indeed fighting in Angola and had ‘saved’ Savimbi’s UNITA from annihilation. Malan spoke out partly at the urging of Britain’s MI-6 intelligence agency, which was deeply supportive of the South African adventure but appalled by the witless conduct of the accompanying public relations campaign.

A senior MI-6 officer responsible for Africa told the author at the time: ‘The South Africans are going to spell out all that they’re doing in Angola too late and miss the prime moment. They are notoriously introvert and secretive. It’s very damaging that they’re not spelling it out to the outside world, but on the other hand their furtiveness is not surprising in view of the way their “friends” have constantly reneged on them.’

Malan said South Africa had been forced to intervene because of the scale of Soviet and Cuban assistance to the Luanda government.

Admitting for the first time that four South African soldiers had been killed in fighting against Fapla and the Cubans in southern Angola, a South African Army communique said their deaths were the result of ‘limited’ support on 9 November to UNITA in operations against ‘Cuban and other Communist surrogate forces.’

Having decided to come clean, the SADF PR men could not bear, for some reason known best only to themselves, to tell the truth fully. They said the four had died in an air raid. In fact, seven South African soldiers died in ground fighting on 9 November on the first day of Combat Group Charlie’s clash with Fapla’s 16 Brigade, which had minimal support on the battlefield from the Cubans. None of the men was named, and none of the many other South African deaths was immediately admitted.

Magnus Malan referred to ‘a Cuban-Russian offensive which forced South Africa into a clear-cut decision – accept the defeat of Dr Savimbi or halt Russian aggression.’

Paradoxically, on the same day – Thursday, 13 November 1987 – that Malan was telling the world that the SADF had rescued Savimbi, the UNITA leader was claiming to journalists at his Jamba HQ that his movement had beaten off Fapla, the Cubans and the Soviets single-handed. ‘There has not been South African intervention,’ he told some 20 foreign correspondents who had been flown into Jamba from Pretoria aboard a 40-year-old twin-prop Dakota of the South African Air Force. ‘We’ve had aid from South Africa but not men fighting at our side. That is categorical ... There is no battle going on here that warrants the participation of the South Africans.’

If Savimbi had been allowed to claim victory for UNITA alone, it would undoubtedly have incensed the 2,000 or more South Africans to the north of him who had just fought a furious battle with Fapla over three days and had seen 11 of their comrades die in that time and a great many more maimed on UNITA’s behalf. It was certainly with this in mind that Malan decided to spike the UNITA leader’s propaganda guns.

Like the incident with the Sam-8 system at the Lomba River, it was indicative of the fact that the SADF’s relationship with the UNITA President was rarely smooth, although Savimbi was less scathing about the South Africans behind their backs than he was about the Americans who had CIA specialists based in Jamba and who must, at times, have liaised with the South African military.

Savimbi was grateful that the South Africans had been consistent in their support. But he never lost an opportunity to express to non-Americans bitter cynicism about the United States which withdrew aid from UNITA in the movement’s hour of greatest need in 1976 and only resumed it again in 1986 when it had become clear that UNITA could not simply be wished out of the Angolan equation.

★ ★ ★

It was against this background that the South African forces to the east of the Cuito River began preparing for the new round of heavy warfare which would mark Operation Hooper. General Liebenberg set 4 SAI and 61 Mech – the former Combat Groups Charlie and Alpha which for Hooper reverted to their normal battalion names – an initial target date of 31 December 1987 by which to destroy the Fapla brigades or drive them across the Cuito. Combat Group Bravo, meanwhile, reverted to its 32 Battalion persona and marauded towards Menongue. 61 Mech was reinforced by an additional squadron of 11 tanks, manned by Citizen Force men of the Pretoria Regiment led by Major Vim Grobler.

General Liebenberg’s target date proved completely unrealistic. The new intake of national servicemen from the training regiments needed more than the allotted three weeks of instruction and rehearsal in Angola to prepare them for the warfare to come. Time and again they practised the art of tank-infantry-Ratel co-operation, first using blank ammunition in their tactical exercises and eventually live ammunition. Savimbi’s public denials of SADF-UNITA co-operation notwithstanding, the regular battalions of his guerrilla organisation joined fully in these co-ordination drills.

There were other problems. Staff officers had not done enough detailed planning. Heavy rains were causing hold-ups. One of the new tank crewmen was severely burned by lightning. Land movements were very difficult, especially across the marshes lining the many streams and rivulets, and the Olifants had to be used as bulldozers to tow trucks through the mud.

Just before Christmas men began to fall ill with hepatitis and cerebral malaria. These were to become grave problems; within 48 hours of the birth of the 1988 New Year the first two SADF men had died from the malaria strain which was a particularly virulent one.

There were major troubles with logistics and supplies. Vital diesel filters for the tanks failed to arrive. By the time Operation Moduler was wound up, ten of the 16 G-5 guns from Quebec and Sierra batteries were out of action, mainly because the seven-metre long barrels of specially hardened steel had worn out. The field commanders were exasperated to find there were neither enough replacement barrels and other spares immediately available nor enough specialist technicians to carry out the complex refitting tasks. Colonel Jean Lausberg had terrible problems ensuring that his gun batteries had adequate supplies of shells, charge packs and fuel. On one occasion the Sierra G-5 battery fell silent. It had plenty of shells, but it had run out of charge packs whose detonations in the breech sent the shells arching towards their targets. Lausberg hitched a lift to Rundu aboard a Puma and made sure that the helicopter returned to Sierra battery the following night packed to its roof with charge packs.

This inefficiency was serious since the G-5s had proved one of the South Africans’ key weapons, more than making up for the problems of technological lag encountered by the SAAF.

The generals, recognising the problems of their field commanders, set a new later date by which the MPLA’s army was to be cleared from the east bank of the Cuito River – Tuesday 5 January 1988.

The SADF set about softening up the opposition, with the six serviceable G-5s playing the main role yet again. The big guns, each firing up to 200 shells a day, concentrated on two main targets – the bridge across the Cuito River from Cuito Cuanavale, and the Fapla brigades dug into defensive positions on the east bank.

The guns pounded the bridge so heavily that on occasions trucks were blown from it completely, and the external fuel tanks of T-54 tanks were set ablaze. By Christmas 1987 the bridge supports had been so thoroughly weakened that it was no longer possible for Fapla to put tanks or other vehicles across it. Supplies getting through by convoy from Menongue were being unloaded on the west bank and being carried across the rickety structure by troops who reloaded them on to trucks on the east bank.

The intensity of the shelling made it impossible for Fapla to carry out repairs by day. On Christmas night 1987 Angolan engineers attempted to close the gap in the middle with a mobile TMM metal bridge, but it fell into the river. However, the engineers persevered and within a few days tanks and trucks were using the bridge again. This made it more important than ever that one of South Africa’s secret weapons be used effectively against the Cuito bridge. A heavy burden fell on the SAAF to perfect quickly its bombing technique with the newly developed H-2 laser-guided ‘smart’ bomb so that the bridge could be destroyed.

G-5 fire rained down upon the Fapla brigades arraigned in a fan-shape in front of Cuito Cuanavale. Between Cuito Cuanavale itself and the Cuito River Fapla’s 13 Brigade was dug in along with one Cuban Army battalion to protect the town in the event of an SADF ground attack across the river. The commander of the Fapla forces had moved his underground bunker HQ from the airfield several kilometres to the northwest of Cuito Cuanavale.

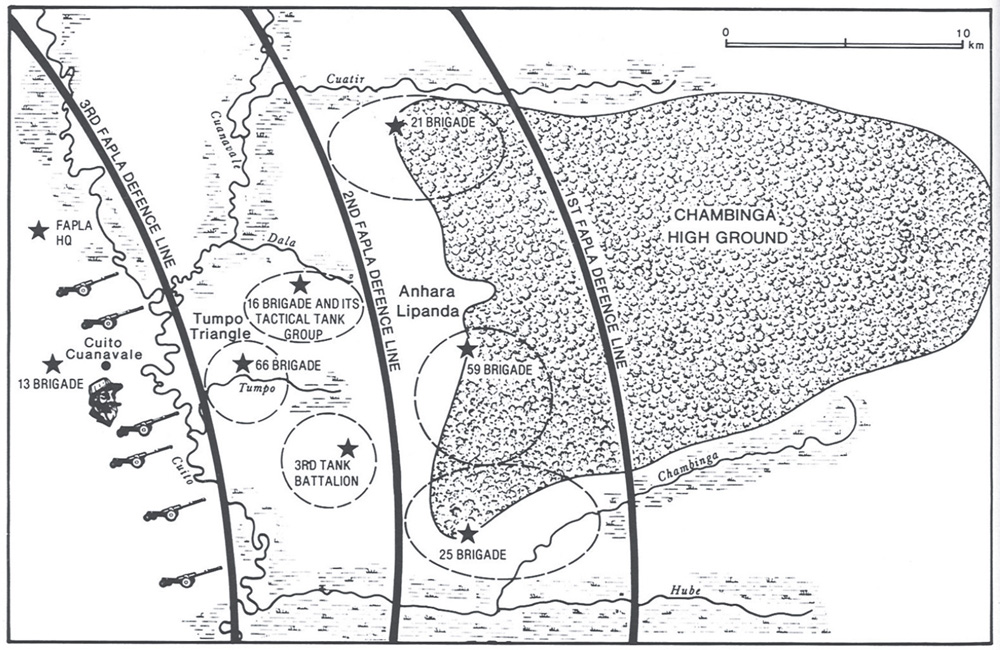

The three defence lines of the Cubans and Fapla east of Cuito Cuanavale at the beginning of SADF’s Operation Hooper: January 1988.

Just across the river from Cuito Cuanavale 66 Brigade, 16 Brigade and its tactical armoured group, and 11 tanks of Fapla’s 3rd Tank Battalion were dug in between the small Dala River and the bigger Chambinga River, about 15 km apart. This area of flat, low-lying ground encompassed the ‘Tumpo Triangle’, between the Dala and Tumpo Rivers, within which was located Fapla’s main logistics base. Sixty or so Soviet-made heavy artillery pieces – D-30s, M-46s and BM-21s – were aligned around Cuito Cuanavale in such a way as to give maximum protection to the base.

Further east 21, 59 and 25 Brigades were aligned in an uneven defensive arc, some 17 km from north to south, on the western edge of the Chambinga High Ground between the Cuatir and Chambinga Rivers. 25 Brigade was just north of the Chambinga. 59 Brigade was some ten kilometres further north again – in a midway position between 25 Brigade and 21 Brigade, which was dug in just south of the Cuatir River.

It was 21 Brigade which had been singled out for elimination first by SA 20 Brigade HQ. It was to be attacked from the east; the plan was for the South African force subsequently to swing southwards and attack and eliminate 59 Brigade from the north.

21 Brigade was spread out over the most northwesterly spur of the Chambinga High Ground, about five kilometres north of the Dala tributary and three kilometres south of the Cuatir.

Just as Major Pierre Franken had played a critical role as a forward observer in the elimination of 47 Brigade on the Lomba River, so his Artillery Regiment comrade Major Robert Trautman was now selected to carry out a similar task against 21 Brigade on the Cuatir River. Trautman was infiltrated by recces into an OP just north of the Cuatir a week before Christmas. He spent most of the following five weeks in the top branches of a single tree identifying 21 Brigade positions and bringing down artillery fire upon them at opportune times.

Like Franken’s role at the Lomba, Trautman’s turned out to be a starring one. Through his binoculars he watched 21 Brigade infantrymen walk to the Cuatir to collect water in buckets, canisters and goatskins every morning at daybreak at precisely the same spot, five kilometres east of the Cuatir’s confluence with the Cuanavale River. Trautman waited until one morning just before Christmas when nearly 50 young Fapla soldiers came down to the river together to gather water. Trautman brought in G-5 airburst shells and afterwards he counted more than 20 dead infantrymen.

The Pretoria Regiment tank squadron was pushed forward for its first action, not in direct combat but so that its 105 mm guns could act as support artillery to the Army’s G-5s and 81 mm mortars. On one day just after the New year the Pretoria Regiment pumped nearly 900 shells into 21 Brigade’s positions while the G-5s fired more than 300 shells and the 81 mm mortars launched some 500 bombs.

On the afternoon of Monday 29 December Trautman was surprised to see a big enemy infantry contingent crossing the Cuatir from north to south at the customary watering point. This, subsequent intelligence confirmed, was the advance guard of a 300-strong 21 Brigade battalion which had infiltrated north of the Cuatir, totally undetected by either UNITA or the South Africans, on a large-scale recce mission to the source of the river. Trautman brought in G-5 airburst shells and subsequently counted more than 60 enemy dead in the anhara lining the Cuatir.

Early the following day the artillery major was surprised to see an even bigger party of men begin to cross the river from north to south. Trautman waited until most of the infantrymen were strung out across the open anhara before bringing in a thunderous rain of 155 mm and 127 mm shells from the G-5s and MRLs.

Trautman reported that of those who survived only 20 made it to the south bank while the rest sought cover among the trees on the north bank. A thunderstorm temporarily obscured Trautman’s vision, but when the rain stopped he saw the battalion attempting to cross the Cuatir once again. He estimated another 40 Fapla dead in the subsequent artillery bombardment. The rest of the battalion stole across during the following night under continuing bombardments lit up by phosphorus flares brought in by Trautman. The major’s final report estimated 120 Fapla dead in the crossing of the Cuatir.

As at the Lomba, the SADF employed a variety of techniques to undermine Fapla morale before the main ground assault was finally launched against 21 Brigade. ‘Ground shout’ teams beamed loudspeaker messages to 21 and 59 Brigades during the night suggesting they retreat because all was lost. Propaganda pamphlets were scattered from special shells fired by the G-5s, which also fired phosphorus illumination rounds during the night over 21 Brigade’s positions to give the Angolans the impression that the SADF had them under constant observation.

The South Africans’ UNITA allies were considerably more impressed by the daylight flares than by the propaganda pamphlets written by the young psychology graduates at Defence HQ in Pretoria. The UNITA men were amused by the leaflets, pointing out drolly to South African troopies that if their psychological warfare experts had been really clever they would have realised that most of the poor bloody Fapla infantry were completely illiterate.

Several SADF psychological warfare teams also spread out to cut trees down with chain saws in the forests north of the Cuatir. Their purpose was twofold. First, to persuade 21 Brigade that an SADF unit was preparing bridges for an attack from across the Cuatir. Second, to select tree trunks the length and diameter of G-5 barrels to set up decoy gun positions, which would be given credibility by moving one or two G-5s up to them now and again to fire a few rounds.

The SAAF was also called upon to weaken 21 Brigade prior to the main showdown. For example, four Mirage F-1AZ fighter-bombers struck at 21 Brigade just after Christmas with a mixture of airburst and delayed action high-explosive bombs, destroying at least one mobile rocket launcher. However, the MPLA won the propaganda war, announcing in Luanda that 21 Brigade anti-aircraft units had destroyed three of the attackers.

While, in fact, all the Mirage raiders had returned unharmed to Grootfontein, the SAAF was finding life tougher than ever before. ‘As far as the Air Force was concerned, Operation Moduler had been a 100 per cent success,’ said Colonel Dick Lord. ‘The air war had been well thought out within our technological possibilities and it had been well executed. Our MAOTs (mobile air operation teams) posted in the front lines with the Army had been invaluable in co-ordinating roles and bringing the planes in on attainable targets.

‘We hit the enemy hard on the Lomba. It is always a good idea in warfare to try to finish a guy off when he is on his knees, so we also hit the Fapla brigades hard as they began their retreat. But for every day they fell back they swung the air war more in their favour. Once they were back across the Chambinga and were being herded by our ground forces into the Tumpo Triangle, our problems became very severe. By chasing them that far our fliers used an Afrikaans proverb to sum up the Air Force’s problems: “Ons speel met die leeu se eiers (We are playing with the lion’s balls).”

‘We kicked the lion’s balls hard. But ops had become much more difficult. A Mirage taking off from Grootfontein to bomb the brigades across the river from Cuito Cuanavale took 40 minutes to fly the 500 km distance, much of it hugging the treetops. It took the same time to get back.

‘The distance meant that so much fuel was used that there was only enough spare to spend two minutes over the target area. This limited the amount of after-burn our pilots could use to give them extra speed in tricky situations. [Extra fuel is used in after-burn to set ablaze gases in the jet engine exhausts, thus giving extra boosts of speed.]

‘The enemy on the other hand had more than 30 Mig-23s and 21s at Menongue, only 180 km from our ground forces opposite Cuito Cuanavale. Flying at height, the Mig-23s were only nine minutes away from the battlefield and they had enough fuel to be able to spend 45 minutes in the target area while using just about all the after-burn they liked.

‘That wasn’t all. The nearer we got to Cuito Cuanavale the more difficult it was to escape the Fapla radar net spread to catch us. They had scores of mobile radars of seven different types (Barlocks, Spoon Rests, early warning Flat Faces, Side Nets, Odd Pairs, Squat Eyes and Thin Skins), with frequent duplication as back-up. The range of the net extended across the Angolan border into Namibia. East German Army units guarded the radars and maintained the electronic equipment.’

Coupled with Fapla’s extensive system of ground-to-air missiles, Lord claimed that the SAAF flew in a more hostile environment than any air force had ever faced. ‘The Israeli Air Force has never faced such a full range of missiles,’ he said. ‘And when its pilots have carried out deep penetration raids it’s been on a one-off basis. Our pilots had to go in deep day-in, day-out. During Moduler they had to fly to avoid Sam-8s, Sam-13s and Sam-9s as well as the normally expected shoulder-launched Sam-7s, 14s and 16s. During Hooper they also came in range of Sam-6s (computer-controlled missiles with ranges of up to 30 km which can lock on to aircraft as close as 100 m to the ground and up to a height of 18,000 metres) and Sam-3s (guided missile used in short-range defence against low-flying aircraft).

‘The more distant our planes were from Cuito Cuanavale, where there was an array of enemy radars, the narrower was the height range within which our pilots could be tracked. By the time they got back to Grootfontein they were right out of enemy radar range at any height. But north of the Chambinga River they were in a “red radar” area which meant they appeared on the enemy screens anywhere down from 7,500 m to 50 m. They were only really safe hugging the ground, because above 7,500 metres they were within the enemy missile envelope or were prey to the Mig-23s.

‘More than ever we had to rely on the superb training and discipline of our pilots, the forward observers and recces, the level of maintenance of our aircraft and the improvements we had managed to make to many of the shortcomings of the Mirages’ French advanced electronics.

‘Air-to-air combat was now completely out of the question for us. The FAPA (Angolan Air Force) had too many advantages in terms of speed, range, radar and survivability, in the shape of numerous little airstrips they could lob into in the case of emergencies.

‘One thing that worked for us was that FAPA, despite the high quality of its Mig-21s, Mig-23s and Su-22s, was among the worst trained air forces in Africa. And it operated according to rigid Soviet doctrine. Our pilots had freedom of initiative while working within carefully conceived plans. The Angolan Air Force guys were given fixed radar and distance vectors on which to fly from Menongue. As they approached the target they were still directed from Menongue Control: “Steer 145 degrees, hold it steady for 46 nautical miles, now drop your bombs,” that sort of thing.

‘It led to such inaccurate bombing from high levels that although they were launching up to 60 sorties a day against our ground forces only four SADF men and two UNITA guerrillas were killed in air attacks throughout the whole of the war in the east. They used all sorts of weaponry – rockets, high explosive bombs, retard bombs, and phosphorus bombs – but they rarely got us. Only occasionally did they come in low to the target, but those ground attacks were mostly unsuccessful as well because they didn’t have forward observers in place to bring them on to the objective. Sometimes they bombed their own positions.’1

[The UNITA Stingers were clearly a factor in forcing the Angolans to fly high, although the SADF was constantly frustrated by UNITA’s poor handling of the American missiles and its low kill rate with them. Although a condition attached by Washington to supplying the weapons was that the SADF be allowed nowhere near them, South African recces helped UNITA Stinger teams to acquire targets and operate the missiles. It would be stretching credulity too far to suppose that the worldly-wise Special Force reconnaissance men did not ensure, in the course of these acts of philanthropy, that one or two examples of the missile did not find their way to Pretoria. Certainly SADF men the author interviewed asserted on occasions that South Africa had its own advanced ground-to-air missiles, though Pretoria has never admitted any such developments. When pressed further on the issue, the military men invariably became coy.]

Despite the best and worst (to wit, the psychologists’ propaganda pamphlets) efforts of the South Africans, Fapla morale did not crack. SADF commandants admired their enemy’s defensive operations and its disciplined control of its artillery – big M-46 130 mm guns delivering 33 kg shells over distances of more than 25 km; highly manoeuvrable D-30 122 mm field guns firing 22 kg shells over distances up to 21 km; and the Stalin Organ BM-21 multiple rocket launchers, firing volleys of forty 78 kg 122 mm rockets at a time over distances of up to 20 km.

Although Fapla’s movements, like those of the South Africans, were now restricted entirely to the hours of darkness, the enemy’s morale had risen greatly and it used the long SADF delay in launching the new offensive to build up its equipment supplies. However, it was not possible for Fapla to make up for its thousands of dead and maimed experienced soldiers with the illiterate teenage recruits who were being drafted ever more rapidly and pushed through their basic training.

Despite its overall lack of success, the Angolan Air Force did force the South Africans to keep their heads down and stay very still most of the time during daylight. The Migs scared the SADF men more times than the most macho of the soldiers were willing to admit.

D-Day for the attack on 21 Brigade was set for 2 January 1988. But 4 SAI, trying to get to the start line, had manoeuvred into a heavily camouflaged position north of the Cuatir River when seven Mig-21s bombed the area. The attack was immediately called off. One bomb fell right inside the 4 SAI laager near a ten-tonne water tanker truck. 4 SAI’s Sergeant-Major Jacques de Wet radioed the tanker driver after the massive explosion, but received no reply. He rushed to where the bomb had exploded only to find the driver making the best of a bad job: shrapnel had punched holes in the bowser and the driver was stripped taking a shower in the precious water before it soaked away into the endless sands of southern Angola.

★ ★ ★

The second D-Day for the attack on 21 Brigade (5 January) also passed as the South African command waited for low cloud and rain so as there would be no harassment from enemy planes. The attack was finally launched on Friday 13 January by 4 SAI, 61 Mech and UNITA’s 3rd Regular Battalion. 4 SAI was led by Commandant Jan Malan, who had replaced Leon Marais in command. 61 Mech was under the temporary command of Commandant Koos Liebenberg, relieving Mike Muller who had been given six weeks leave to move his family and furniture from the Republic to 61 Mech’s permanent staff HQ at Tsumeb in northern Namibia. UNITA’s Chief of Staff, General Demostenes Chilingutila, a tough little soldier who had once been a sergeant in the Portuguese Army, had taken direct control of the 3rd Battalion for the strike on 21 Brigade.

The plan was for 4 SAI and UNITA’s 3rd Battalion to carry out the main attack, coming from east of the Cuatir River source over the Chambinga High Ground. 61 Mech would manoeuvre between the defensive works of 21 and 59 Brigades and position itself on a densely forested hill, which became known as 61 Koppie, three kilometres south of the 21 Brigade perimeter and just north of the Dala River source. 61 Mech had a dual flank force role – to prevent Fapla reinforcements reaching 21 Brigade from the south; and to hit 21 Brigade if it broke and started running for the safety of the Tumpo Triangle. Once the battle was over, UNITA would permanently occupy the abandoned 21 Brigade position.

21 Brigade had two outposts on the crest of the Chambinga High Ground to the east of its main position – one just two kilometres south of the Cuatir River and the other three kilometres further south again. UNITA’s 3rd Battalion was to eliminate the northern outpost while 4 SAI wiped out the southern one.

4 SAI began its approach past midday after the usual early morning softening up of the enemy by the G-5s and MRLs. Together they fired some 300 rounds into the main 21 Brigade positions, and this was followed by the 81 mm and 120 mm mortars and then the SAAF whose bombs set a bush fire raging near the enemy HQ.

4 SAI comprised the most formidable South African combat group to go into battle since World War II – a central column of every variety of Ratel, with nearly 1,000 infantrymen mounted, and support vehicles, and two flanking columns each comprising 11 Olifant tanks.

The Attack by 4 SAI and 61 Mech on Fapla’s 21 Brigade: 13 January 1988.

Yet again, an SADF force was surprised by the density of the Angolan bush. Progress was slower than had been planned in the neat exercises fought by staff officers at tactical HQ on their forest floor sand models. The roar of engines as the Olifants and Ratels ploughed through the tangled trees and undergrowth quickly alerted Fapla to the fact that an attack was underway. Heavy artillery and mortar fire began to rain down among the South African armour, causing no casualties but forcing all the Ratels and Olifants to fasten their hatches.

4 SAI met little opposition at the southern outpost so it turned north to help UNITA on the northern objective where life proved tougher. The battalion first ran into an anti-tank minefield – a Ratel lost a wheel when it detonated one of the mines. Then the small Fapla force fought with unexpected grit and courage, retreating in orderly fashion from bunker to bunker and maintaining a steady stream of fire as the Ratels and Olifants advanced in 200 m bounds. An Olifant drove right up to one bunker containing 20 or so Fapla infantrymen who had fought with particular valour and fired into it a high explosive shell which killed all of them instantly.

By mid-afternoon 61 Mech had reached its protective position on the flank and 4 SAI and the 3rd Battalion were ready to attack the main 21 Brigade position. 4 SAI’s progress was tortuous. Three tanks lost their tracks swinging across the uneven terrain and had to be taken back to the laager area by recovery vehicles. A Ratel lost a tyre when it ran over an anti-personnel mine. Then a Mig-21 raid put another Olifant out of action when flying shrapnel from a Mig bomb shattered the sight periscope of the South African tank.

Only an hour of daylight remained when 4 SAI finally moved into the attack on the main enemy position under very heavy artillery, mortar and small-arms fire.

While the Olifants were taking out bunkers systematically the thinner-skinned Ratels were suffering under a deadly hail of fire from Fapla’s 23 mm guns, each firing hundreds of armour-piercing slugs per minute which exploded from the gun muzzle at a speed of 3,500 km per hour. Two Ratels were quickly put out of action – one when a 23 mm round destroyed the driver’s periscope and the other when one of the solid metal projectiles penetrated a turret and slammed out through the opposite side, narrowly missing the head of a crewman on its journey.

The Citizen Force tankmen of the Pretoria Regiment won their first scalps when enemy tanks attacked from the flank and the Olifants’ guns knocked out two of them. Progress was now rapid for the first time in the day as the Olifants and Ratels drove over anti-personnel minefields to clear a passage onto the target for the infantry.

A fusillade of direct rocket fire at a range of just 150 m from a Stalin Organ threw the track off another Olifant, but now the battle was virtually over as the South African tanks ran over the Fapla bunkers and took out the deadly 23 mm guns one by one. Just before sunset the Pretoria Regiment shot out another two tanks and 21 Brigade began to break and run towards the Cuanavale River.

Commandant Koos Liebenberg was surprised to find enemy tanks, trucks and infantrymen fleeing for safety between his own 61 Mech vehicles at the flank position. The Ratel-90s shot out three of the retreating tanks and four armoured cars, but were so shocked by the appearance of a platoon of nude Fapla soldiers in their midst running at high speed that they failed to react in time and the streakers got clean away.

When darkness fell Commandant Jan Malan tried to press home the South African advantage by the light of illumination rounds fired by the G-5s and 120 mm mortars. But the dust of battle and gathering thunder-clouds reduced visibility drastically. 4 SAI had to pull back and returned at first light to clear up and confirm that the whole of 21 Brigade had retreated.

4 SAI swept down from the Chambinga High Ground and reached a point just ten kilometres from Cuito Cuanavale on a road running north eastwards from the Cuito Bridge. From there Colonel Paul Fouché ordered Commandant Malan to clear the east bank of the Cuito River north of the Dala of all Fapla soldiers. 4 SAI encountered little resistance and shot out four enemy armoured cars and a field gun and gathered up a lot of intact Soviet equipment, including five tanks and two M-46 field guns. UNITA anti-aircraft units operating alongside 4 SAI with captured ZU-23 guns had a conspicuous success when they shot down an enemy Mig-21.

4 SAI and 61 Mech withdrew to their laagers to the east of the Chambinga High Ground on the evening of Saturday 14 January 1988. By any normal method of tallying, they had reason to feel they had done a good job. Seven enemy tanks had been destroyed and five captured intact; four armoured cars had been destroyed and two captured intact; rocket launchers and various field guns had been destroyed and three more Sam-8 missiles (not entire systems) had been captured. Fapla had lost an estimated 150 dead and wounded. Against that only one South African had been wounded, and he shot himself accidentally, and UNITA admitted in one of its regular press communiques to four dead and 18 wounded.

And yet the SADF knew that by its own standards it had flopped yet again. It had failed to annihilate 21 Brigade; the majority of 21 Brigade’s personnel escaped to the Tumpo Triangle, where they began reforming and were made up to strength again by the addition of units from other brigades. The SADF did not follow up and immediately destroy a demoralised enemy because its own numbers on the ground were extremely limited, as a result of the transfer of 32 Battalion to the Menongue operation and because the logistics support was inadequate.

The two tank squadrons desperately needed new tracks and back-up spares. Some vital spares ordered ten weeks earlier had still not arrived in the forward areas by mid-January. For the first time the Ratels also suffered a serious spares crisis. Clean overalls requested by tiffies in early December 1987 did not arrive until the end of the first week of February 1988, by when they were very niffy tiffies indeed. There was also a desperate shortage of fresh rations. Some artillerymen had seen no fresh meat or fruit for ten weeks: this was not only demoralising but also extremely debilitating in a hostile environment of sweaty heat, alternate dust and pounding rain, and dense clouds of black flies by day and whining mosquitoes by night. It was little wonder that disease began claiming men at an even faster rate. Cerebral malaria posed a terrible problem and hepatitis was sapping the South African strength dramatically: by early February more than 100 men had been evacuated with severe hepatitis from 4 SAI alone.

Morale was further dented when a 61 Mech serviceman was killed in a stupid accident. As his Ratel sought cover during an air raid alert he was crushed to death between the open hatch and a heavy overhanging tree branch. And towards the end of January Robert Trautman, still up his tree north of the Cuatir, reported that 21 Brigade was re-occupying the positions from which it had been driven in the 13 January battle.

Major-General Willie Meyer, the Commander of the South West Africa Territory Force (the Namibian extension of the SADF), was seen as a Job’s comforter when he visited the front and tried to lift the troops’ low spirits by suggesting that it was sometimes desirable to let an enemy retake a position so that it could be destroyed completely in a later attack!

21 Brigade dug into its old positions along a two kilometre-long north-south line and began laying protective minefields, as did 59 Brigade further south. Meanwhile, another battalion of Fapla’s 66 Brigade was sent across the Cuito River to reinforce units already defending the Tumpo Triangle logistics base. Other reinforcements followed, and by early February there were nearly 50 Fapla T-54/55 tanks on the east bank of the Cuito River. In addition, units from Fidel Castro’s elite 50 Division, normally assigned to guarding Havana, began to arrive in Cuito Cuanavale after embarking from Cuba two months earlier.

50 Division was under the command of General Arnaldo Ochoa Sanchez, head of Cuba’s military mission in Angola.

Castro, while sending his precious 50 Division to Angola, also asked Angolan President Eduardo dos Santos if Cuba could take over responsibility for defending Cuito Cuanavale, with Fapla forces there coming under Cuban command. Dos Santos said yes, and Castro set up an operations room in Havana from which he could follow the progress of the Cuito campaign, often issuing his own direct orders on how things should be conducted.

Ochoa Sanchez, a man of striking appearance who was popular with his troops, felt that he was being asked not to make a Homeric defence of Cuito Cuanavale but to cover a retreat that Castro had already decided would be necessary. He was gloomy about the task which had been set him and Fidel’s brother, defence minister Raúl Castro, quoted Ochoa Sanchez as telling him: ‘I have been sent to a lost war so that I will be blamed for the defeat’.2

It took until 25 January for the SADF high command to decide what the next target would be. 59 Brigade, the strongest of the defending enemy units, would be directly attacked in the belief that its collapse would force 21 and 25 Brigades to fall back towards Cuito Cuanavale without additional fighting.

1 Deon Ferreira said Brigade HQ had confirmed evidence of the Angolan Air Force bombing its own frontline infantry on at least six occasions.

2 Business Day (Tuesday 18 July 1989).