Commandant Gerhard Louw was appointed a tank and armoured car instructor at the South African Army Battle School at Lohatla in the dry brown expanses of northern Cape Province in early January 1988. Tall, erect and broad-shouldered, Louw was a highly disciplined career officer in his early thirties who took his soldiering very seriously. In his intensity, he bore more resemblance at first acquaintance to an officer of the British school than the more anarchic and quarrelsome Boer tradition.

Battle School’s main responsibility was to keep the Citizen Force, comprising almost 80 per cent of total army strength, up to scratch with modern warfare techniques during its periodic call-up sessions. Citizen Force tank soldiers from the Orange Free State’s Regiment President Steyn were mobilised in Bloemfontein at the beginning of February 1988 for Colonel Paul Fouché’s 82 SA Brigade. Louw moved to the School of Armour in Bloemfontein for a fortnight to help resident instructors prepare the Citizen Force men for battle. They were helped by men from 4 SAI and 61 Mech who had already fought in the front line of the War for Africa.

Louw and the team of instructors flew from Lohatla to Rundu at the end of February to await the overland arrival of Regiment President Steyn with its pristine tanks. Louw established a training area six kilometres inside Angola from Rundu and continued preparing the Citizen Force men there until 10 March, when 61 Mech and 4 SAI passed them on the way out with their battle-fatigued Olifants.

‘We didn’t really have enough time to train the men thoroughly,’ said Louw. ‘In the nature of things, it takes more time to get men who have been back in civilian life ready for battle than it does career soldiers or national servicemen.

‘Our life wasn’t made easier by logistical problems. One of the two tank squadrons of Regiment President Steyn came all the way from Bloemfontein to Angola without its mounted 7.62 mm machine-guns. We had to get the men used to the terrain, the climate and the equipment and train them in drills, tactics and co-ordination in a very short time. When the time came to move deep into Angola they still weren’t fully operational, mainly because we’d been hampered by ammunition shortages and equipment shortfalls and failures.’

Louw had travelled to Rundu and across the border to put the Regiment President Steyn through more intensive training before waving them off to the warfront and returning to his instructor’s post at Lohatla. But in January and February 1988 South Africa was hit by its heaviest rainfall and worst floods in decades. The farm and home of President Steyn’s Citizen Force commandant were seriously damaged by the floods.

‘His business was virtually swept away,’ said Louw. ‘He faced terrible financial troubles, and so he was unable to assume command. As the man on the spot, I was asked to take over command of the two Citizen Force tank squadrons and lead them into battle, even though I was Permanent Force.’

While the training continued, Louw heard that Mike Muller’s second attack on Tumpo had failed. It did not surprise him. In his capacity as an armour instructor, he was deeply sceptical about the wisdom of sending tank forces into open ground sown with minefields and enfiladed by a formidable array of heavy artillery overlooking the battleground.

Louw sent the A and B Olifant squadrons of Regiment President Steyn off to the Brigade tactical HQ east of the Chambinga High Ground. The Citizen Force men got their taste of the harshness of the Land at the End of the Earth as they ploughed day and night through the deep sand of the vague tracks in the forests and across the grasslands of southeast Angola. Louw himself moved back to Rundu in a Ratel, and was flown from there with his training team to the tactical HQ to receive his orders for a third tank attack on Tumpo from Colonel Paul Fouché.

Louw now had to overcome a typical problem thrown up by the half-cock conduct of the latter phases of the War for Africa, with the battlefield officers never quite knowing from day to day what new limitations or expectations might be placed on them by the politicians and diplomats.

‘When South Africa called up its first troops for the campaign, they were committed piecemeal, with mechanised infantry designated for the primary role,’ said Louw. ‘Thus 4 SAI was committed with a tank squadron attached under the command of a mechanised infantry commandant and his infantry battalion HQ. The same went for 61 Mech.

‘As operations evolved it became clear that the “subordinate” tanks were the most effective weapons in bush that, theoretically, was infantry terrain unsuitable for tank warfare. The enemy fought with tanks, and the UNITA infantry couldn’t face them effectively. The enemy infantry had the same problem with the Olifants.

‘As it became clear that our tanks and Ratels were achieving more successes – the armour of the Olifants was not penetrated once by enemy fire – and as our artillery demonstrated its superiority, the South African infantry took a less and less prominent role, especially in view of our orders to keep casualties to an absolute minimum.

‘But something was wrong with the analysis when 82 SA Brigade was formed. The Citizen Force units called up did not constitute a full tank regiment, even though it was perceived the battle would be based on a tank regiment-led assault. The units called up were structured in the same way as those which had just been withdrawn. I was a whole squadron of 11 tanks short to be able to form a proper regiment. I had no proper regimental HQ, only two infantry battalion HQ structures as provided for 61 Mech and 4 SAI. That made my tactical problems very complicated and involved. I had to form a makeshift regimental HQ with only one tank and with the rest of the staff supplied by a De La Rey Citizen Force infantry battalion. It was frustrating and time-consuming.’

Once Louw had established his rough and ready HQ, he began last-minute training of the President Steyn tank squadrons in regimental tactics, marrying up with the De La Rey infantrymen and the soldiers of UNITA’s 5th Regular Battalion. Louw was shocked to find that the UNITA battalion was way below its ideal strength of 700 men because of combat attrition. ‘By the time HQ personnel, signallers, cooks, bottlewashers and the rest had been taken into account, they only had about 200 fighters.’

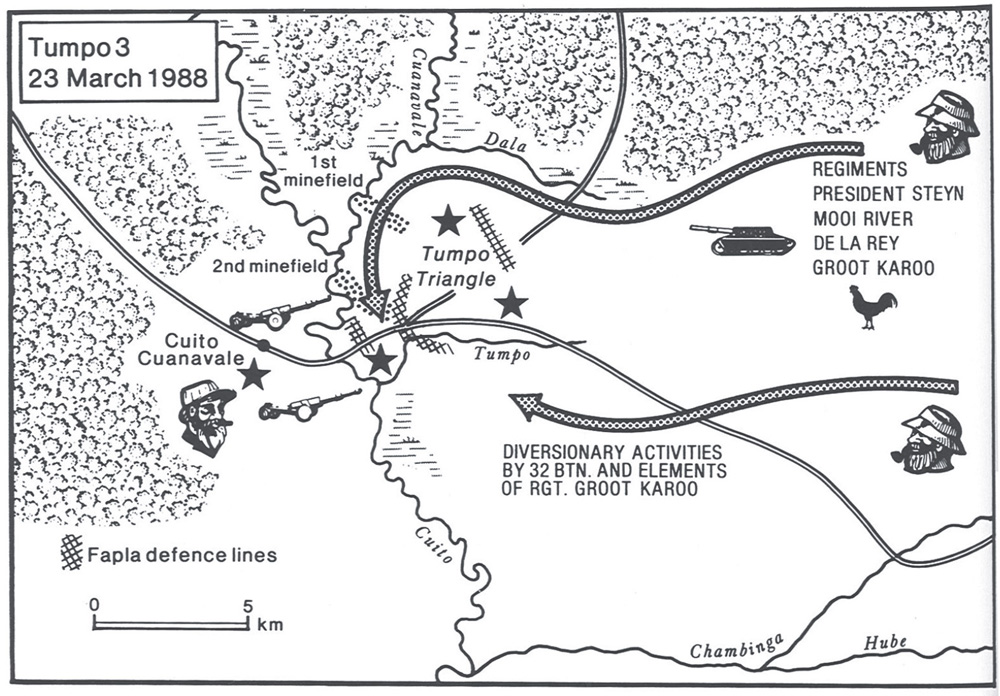

The generals, having wind of Crocker’s and Botha’s ambitions, pressed Colonel Fouché to get on with Tumpo Three before the military were overtaken by diplomatic events. Fouché, plagued by similar logistics problems to those which had bedevilled Pat McLoughlin, secured one postponement of the attack. But in due course he was able to signal Brigadier Fido Smit in Rundu that Tumpo Three would be launched in the early hours of Wednesday 23 March 1988.

Commandant Gerhard Louw’s mission was to drive the enemy out of the Tumpo area; hold the captured terrain until last light on 23 March; and allow field engineers, two companies of infantry from 32 Battalion, UNITA’s 5th Regular Battalion and recces from 4 Reconnaissance Commando to move in to blow up, once and for all and comprehensively, the bridge across the Cuito River.

Louw’s force to deliver the final SADF blow in the battles east of the Cuito River was assembled and moving into its positions by the afternoon of 22 March. Louw’s own main attack formation comprised the A and B Olifant squadrons of Regiment President Steyn, plus the Regiment Mooi Rivier Ratel squadron and two mechanised infantry battalions of the Regiment De La Rey and Regiment Groot Karoo.

The Artillery Regiment Potchefstroom University provided support in the form of one battery of G-5s and one battery of World War II-vintage G-2 guns with a maximum range of scarcely 16 km. The mobilisation of the G-2s was an indication both of the degree of punishment the G-5s had undergone and of the limited production of the weapon to that date.1 44 Parachute Brigade provided a 120 mm mortar battery and 19 Rocket Regiment a troop of four MRLs.

Besides its 5th Regular Battalion, UNITA also sent into battle its 3rd and 4th Regular Battalions and two semi-regular battalions on the east bank of the Cuito. Another two semi-regular battalions were deployed on the west bank to launch hit-and-run attacks on outlying Fapla positions around Cuito Cuanavale.

Major Tinus van Staden’s three 32 Battalion companies operated over the Chambinga High Ground and down Heartbreak Hill, to the south of Louw’s planned northern attack line, towards the Anhara Lipanda. Van Staden was reinforced by an infantry company and anti-tank and anti-aircraft units from the Regiment Groot Karoo.

In the days leading up to Tumpo Three, 32 Battalion and Groot Karoo troops were assigned various tasks. 32 Battalion, assisted by UNITA’s 4th Regular Battalion, deployed on the steep western slope of the Chambinga High Ground with the dual responsibility of sweeping the area for mines in advance of Louw’s attack and stopping any Fapla reconnaissance patrols from moving east of the Anhara Lipanda.

The UNITA 4th Battalion performed impressively, lifting more than 200 mines in early March. Liaising with them was 32 Battalion’s Lieutenant Thai Theron, Captain Piet van Zyl’s friend who had vowed the previous November at the “Club Mediterranée” lagoon that if he ever lost a leg in warfare he would commit suicide.

On 9 March Thai Theron, on night patrol on the Anhara Lipanda, stepped on a Soviet anti-personnel mine and his right foot was blasted away. Theron was removed quickly by helicopter. After surgery he was fitted with an artificial foot. Theron did not take his own life, and after extensive physiotherapy he returned to 32 Battalion to become Van Staden’s second-in-command in the training unit.

The Regiment Groot Karoo units attached to 32 Battalion were very active southeast of the Tumpo River in an attempt to distract Fapla’s attention from the direction of the main attack. The Groot Karoo men built simulated bridges, made obvious movements and generally made a lot of noise.

The SAAF went into action again in an attempt to soften up the enemy. Mirage F-IAZs made two bombing attacks right into the Tumpo Triangle, but after another raid on 19 March on the Fapla battalion stationed at Baixo Longa, 80 km southwest of Cuito Cuanavale, fresh tragedy struck. Ed Every’s flying colleague and friend from 1 Squadron, Major Willie van Coppenhagen, crashed and was killed in northern Namibia on his way back to Grootfontein. He had reported no problems or damage after the attack, and the Air Force inquiry team concluded that he had developed a technical problem, temporarily lost orientation while trying to deal with it, and crashed before he could make good.

★ ★ ★

Louw’s force moved out from Brigade tactical HQ about 4 pm on Tuesday 22 March and reached the assembly area on the eastern slope of the Chambinga High Ground just before dusk at 7pm. ‘Logistics had been a constant nightmare while we were getting prepared.’ said Louw. ‘A lot of vital equipment I had been asking for reached us only just in time, things like night vision periscopes which were needed for the movement we faced in darkness, heavy machine-guns for one of the tank squadrons and “chest boxes” for the signallers.’

In the assembly area Louw established a logistics supply point and rearranged his tanks and the trucks carrying UNITA infantry into a column consisting of two ‘line ahead’ formations moving parallel to each other. It fell dark as the column moved forward. Louw established a surgical post as his force went down Heartbreak Hill, heading for the ‘waiting area’ on the eastern edge of the northern lobe of the Anhara Lipanda, due east of the source of the Dala River.

‘We got lost once on the way,’ said Louw. ‘A recce group had gone out and plotted the route, and they actually led the advance. But the terrain was all sand-dune hills covered with trees, and we came to one point where a lot of sandy tracks met and then split. The recces got confused in the dark and took the wrong route. They realised after about a kilometre, but you can’t turn around an armoured column in most conditions, let alone those.’ The recces scouted south to find the lost track, and then led the column through dense bush to rejoin the appointed route.

A 32 Battalion company was at the ‘waiting area’, about six kilometres from the forward Fapla trenches manned by 25 Brigade, when Louw’s column began moving in at 4 am on 23 March. The black Angolans of 32 Battalion had marked the final part of the line of attack for Louw with ‘close sticks’, which are implanted in the ground and, once their tops have been broken off, glow with a greenish phosphorescence from the chemicals inside.

‘I was supposed to start moving at 6 am, but the sky was overcast and it was still dark,’ said Louw. ‘I decided to postpone my advance until 6.15 when we could see better to change our night periscopes for day periscopes. The night periscopes are heavy and it’s not a simple action. I wanted to move out with day periscopes so that we weren’t faced with the problem of changing them in the middle of the battle itself.’

UNITA’s infantrymen took position on the engine plates of the Olifants as the tanks moved out onto the Anhara Lipanda. After about a kilometre the first enemy artillery fire began. ‘For those of us in the tanks, it was no hassle,’ said Louw. ‘An artillery round only really endangers a tank with a direct hit. The UNITA men were OK at that stage as well because the artillery fire was very inaccurate and sporadic.

‘Then as we moved forward we received a radio warning of an enemy air raid. The drill on such occasions is for tanks to scatter on order from the commander. But they dispersed like cockroaches in a floodlit kitchen without waiting for the command. I bawled them out on the radio, not least because the planes proved to be our own Mirages trying to bombard 25 Brigade. They had to pull out of the attack because the cloud was too dense. I pulled the tanks together again in double column, and we were going along quite well on Mike Muller’s earlier tracks when our artillery opened up on the enemy positions.

‘Once we were across the Anhara Lipanda we could just see Cuito Cuanavale itself to the southwest across the Cuito River. It was then that we hit our first minefield. We were still in columns of two, but only one mine roller had arrived and the right-hand column had to enter the minefield without an advance roller. There was a bang. A mine had blown a track from one of the tanks and a bogey wheel came flying over my head.’

Louw halted the advance and called field engineers forward to clear a way through the minefield. It was now about 9 am. One of two plofadders with Louw’s force was moved forward. Five hundred kilos of explosive in the plofadder sausage string shot out. But the braking mechanism did not release the rocket properly, so the sausage failed to stretch right across the minefield, and, yet again, the plofadder failed to detonate automatically.

The engineers prodded their way forward to the front end of the plofadder and detonated it manually. But they reported back to Louw that because it had not deployed right across the minefield the obstacle had not yet been properly breached.

‘I ordered the other plofadder forward,’ said Louw. ‘It fired from the same position and deployed properly, but once again it did not detonate automatically. The engineers went forward this time in a Ratel to detonate from the front. The Ratel hit an anti-personnel mine, which blew one of its tyres, so the engineers went the rest of the way to the front on foot with mine-detecting equipment, plucking out a few more anti-personnel mines by hand on the way. Then they detonated the plofadder manually.

‘All this held up the advance for two-and-a-half hours. Enemy artillery, particularly BM-21s, fired at us all the time. But everyone was quite calm. We weren’t in real danger at that stage. We were on a slight slope coming up from the Dala River towards Cuito Cuanavale. We weren’t visible and the rockets tended to pass over our heads and fall into the Dala Valley: the anhara lining the river there became heavily pockmarked with blackened shell craters.’

Louw’s tanks had encountered a ‘warning’ minefield of a very sophisticated defence system organised by Cuban General Ochoa Sanchez’s top field commander, General Cintra Frias, in the Tumpo Triangle and Cuito Cuanavale area.

Cintra Frias had planned according to Soviet Army landmine operations doctrine. This states that the key purpose of a minefield is not so much to inflict damage on attacking vehicles as to channel them into predetermined kill zones covered by massed artillery fire and anti-tank missiles. The minefields, containing a variety of explosive devices, are sown in several belts, usually up to 300 m wide and 50 m or more deep.

Fapla’s 25 Brigade had lost more than 150 men in the Tumpo Two battle, but the unit had not been destroyed. Cintra Frias made the survivors dig in deeply in well-prepared trenches and bunkers behind the minefield belts. They were supported by a formidable array of different artillery pieces immediately behind them within the Tumpo Triangle and on dominating higher ground on the west bank of the Cuito.

Directly behind 25 Brigade, in the Tumpo Triangle, was Fapla’s 66 Brigade and 16 Brigade’s old tactical armoured group, now dominated by the Cuban-manned 3rd Tank Battalion. Spare tanks had been brought across the Cuito on metal ferries until there were a dozen or more in firing positions behind 25 Brigade’s lines. Any attacking force which reached Fapla’s forward trenches would inevitably face a torrid reception from an enemy which had prepared skilfully in advantageous terrain, and whose confidence was high after beating back both the Tumpo One and the Tumpo Two attacks.

Louw moved the President Steyn tanks in single file across the minefield through the lane cleared by the two plofadders. They were led by the lone Olifant with a mine roller attachment. The Ratel squadron of the Regiment Mooi Rivier stayed back at this stage in a covering role.

‘I sent A Squadron through first,’ said Louw. ‘I followed in my own command tank. B Squadron followed behind me. As we came over the rise above the Dala it was still overcast, but there was sun getting through and we could see the whole of Cuito Cuanavale spread out before us. We now had to move down a slight slope and up another to get to the Tumpo area itself.

‘We started drawing heavy fire because, for the first time, the Fapla could see exactly where we were. The dust clouds from the plofadder explosions had given them the first target pinpoint, and now they were firing at us with just about everything they had, including some Sagger anti-tank missiles passing overhead at more than 400 km per hour. It got heavier and heavier and more accurate.

‘It was about midday. Despite the artillery barrage, I managed to get the A Squadron commander to get his tanks into combat formation. B Squadron to his left was having difficulties forming up. A Squadron started to move forward, but because the bush was very dense at that point I couldn’t establish a link between the two squadrons. We had to stop A Squadron just as they were beginning to emerge from the trees into open area, which was Tumpo itself. The open area used to be subsistence farming land years ago: many trees had been cut down, so all that faced us from that point was open grass on sand on the east bank of the Cuito.

‘Eventually I got B Squadron formed up and I ordered both squadrons to begin moving forward again in extended combat line abreast. Each tank was firing intensively at speculative targets as it advanced. The poor UNITA guys were beginning to take hideous casualties, especially from the 23 mm guns. Soon after the Olifants started moving three of them hit mines almost simultaneously. Fapla must have sown boosted mines because this time I saw not only bogey wheels but whole suspension units sailing through the air.

‘I told everyone to stop and we went into a “fire girdle” action in which each tank commander fires independently whenever he thinks he has seen a target. The enemy had us pinned down in the minefield for the time being, and they had the chance of shooting out the Olifants one by one. Fortunately the minefield was just inside the treeline. If it had been on the open ground they would have knocked out more of us.

‘One of our ARVs managed to tow out one of the tanks. A second ARV attached itself to another tank but couldn’t move it. I moved my command Olifant to see what the problem was. A boosted mine had blown off the whole rear suspension unit and the tank had tilted and fallen into a hole, where it was stuck fast. I got out of my tank and directed the driver so that the ARV was towing the crippled Olifant and my tank was towing the ARV.

‘By now the enemy seemed to be throwing everything towards us, including phosphorus bombs. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw missiles whistling over our heads. They had BM-14s and BM-21s firing horizontal rocket salvos at us from the opposite bank. Fortunately all the rockets landed in front of the tanks and the rocket boosters and motors tumbled over our heads and caused no losses. It was a big noise, of course, lots of noise and so much smoke and dust that I could barely see my tanks.

‘Mortar shells landed all over the place and 23 mm slugs crashed through the sound barrier. We were in danger of being well and truly pinned down in a sea of mines, so I gave A Squadron permission to withdraw for a distance but then to stand firm and give cover while we extracted B Squadron.’

As Louw’s Olifant and the ARV took the strain of attempting to pull out the tank with the destroyed suspension from its hole, they detonated several anti-personnel mines. ‘It was strange that none of us had stepped on any of these, because we had been crawling all over the show to get the tows fixed,’ said Louw.

The disabled tank proved impossible to move. ‘The more we pulled it the deeper it dug into the sand.’ said Louw. ‘I decided we would have to cut loose and leave the tank in the minefield for the time being. I got out of my Olifant and ran to the damaged tank, rapped on the hatch and told the guys there to get out and run to my tank and the ARV.’

Louw returned to his command Olifant to make radio contact with Brigade HQ which was now in a state of high anxiety about the progress of the Tumpo Three attack. Louw told them to hold fast: he was trying to get the Olifants back into combat line. He leapt out of his tank again and ran between exploding mortars, rockets and bursts of 23 mm fire to the ARV, which was not on his radio net, to tell the tiffies to unhitch their tow from the Olifant.

‘I got my own tank untied,’ said Louw. ‘That was no problem. But the ARV was attached to the stuck tank with an iron bar and shackle which had been under such strain that the bar buckled, leaving the Olifant virtually fused to the ARV. None of the tiffies’ tools worked, and in the end they had to use a metal saw to get free.’

Louw turned his attention to the third damaged tank, the one with the mineroller attached. One of its tracks and a bogey wheel had been blown off. It was hitched up to three tanks in line from B Squadron, which were dragging the Olifant away at snail’s pace as it scraped a deep furrow in the sand.

‘The mineroller made the damaged tank extra heavy,’ said Louw. ‘We had techniques for disconnecting the roller quickly, but apparently nobody was willing to get out of the tank to do it. The towing was very difficult, and the squadron commander was concentrating so hard on the problem of maintaining movement that he was going in the wrong direction. He should have been moving northwards into the treeline away from the Fapla artillery. Instead, he was drifting eastwards, moving parallel to the enemy positions and offering a maximum target area.

‘When you’ve got four heavy tanks moving tied together in that way they can’t change direction quickly. If you turn at a sharp angle you can’t drag 56 tonnes of armour and steel with you. The turn has to be gradual and smooth over a long distance. I ran across to the squadron commander and he reckoned it would take another kilometre and two hours, at the rate they were travelling, to change the formation’s direction, by when they would be well past the entrance to the cleared lane through the first minefield.

‘It was now about 2 pm. The artillery barrage had not let up at all, and, with the unexpected exertions the tanks had been guzzling fuel faster than expected. I asked for permission to break off the attack, and Colonel Fouché granted it.’

Louw decided that the tank in the hole and the mineroller tank could not be recovered without seriously endangering the withdrawal. All the shackles anchoring kinetic towing ropes to the mineroller tank had also bent so severely that they could not be detached. ‘I gave orders to cut the towing ropes, but they were too tough for our military knives,’ said Louw. ‘Finally, we severed the ropes with machine-gun and automatic rifle fire.’

Louw walked to the now abandoned mineroller tank and, as he had with the other beleaguered Olifant, beat heavily on the battened hatch and ordered the crew to get out and scramble fast to the other tanks.

‘There was no time for them to grab personal items,’ he said. ‘Bushes and the tops of trees were being swept away by the artillery and 23 mm fire. One shell hit my tank. I didn’t know where at the time. I just heard a clang and the explosion. I drove it back and forward for a while, and since nothing seemed wrong I concluded that it couldn’t have been a proper hit. But days later it was pointed out to me that the shell had hit my gun barrel and there was a big dent on the inside. If I had tried to fire, I would have ended up with a drastically shortened barrel!’

Louw now asked Colonel Fouché for permission to destroy the two crippled tanks since there was a real danger they would be captured by Fapla. General Kat Liebenberg, who was with Fouché at the Colonel’s forward tactical HQ about 20 km from the battlefield, stepped in with an order that the Olifants were not to be wiped out but left in the minefield for recovery later.

‘As we moved out we rolled over anti-personnel mines everywhere and detonated them,’ said Louw. ‘We carried several UNITA casevacs who had been wounded by artillery and mine shrapnel. At first, I couldn’t find the entrance into the lane back through the first minefield. We wandered around in the bush and I was really scared that we were going to veer into the minefield and lose more tanks.

‘I radioed for one of the Mooi Rivier Ratel-90s to move along the cleared lane and fire signal flares to mark his position so that we could move up to him.

‘As we approached the entrance one of the Olifants threw its track. It had nothing to do with the mines. It was purely a mechanical mishap. We had no kinetic ropes left, so we had to leave that relatively undamaged tank behind for collection later while the rest went single file along the path cleared earlier by the plofadders.

‘We moved through to a former hamlet called Cabarata, on the south bank of the Dala, where UNITA stayed more or less permanently. It was about 4.30 pm and the Fapla Migs were in the air for the first time that day. I don’t know why they had been so inactive. They used the SAAF’s “toss-bombing” technique, but the bombs landed far away from us. We put the tanks under the trees and camouflaged ourselves to the best of our ability. We were still within enemy artillery range, and when shells started landing among the tanks I thought, hell, let’s get out of range, air warnings or no air warnings.’

Louw’s force moved through the ‘waiting area’, dropped off the UNITA casualties at the surgical post and then moved to a point further north, where it spent the night out of artillery range before moving back on 24 March to its training area near Brigade tactical HQ.

Tumpo Three was the only clear defeat the SADF suffered in the War for Africa. The assault had achieved nothing for the South Africans. Many UNITA soldiers had been killed and wounded. Five Olifants were damaged, and only two of those had been recovered.

‘We got orders on 25 March to destroy at all costs the three Olifants we had left behind, as we had wanted to do before we withdrew from the battlefield,’ said Louw, who was subsequently decorated with the Honoris Crux for bravery for his conduct in the enemy minefields. ‘But it was too late. A 4 Recce commander and UNITA special forces reported that Fapla and the Cubans had pushed out a company of infantry immediately after we withdrew to dig in around our tanks. We tried to devise all kinds of plans to penetrate their defensive perimeters and recover the Olifants, but we weren’t able to implement them.’

The capture of the Olifants was a major propaganda and intelligence coup for Fapla and the Cubans. It enabled them to offer solid evidence for the version of history they were giving to the world – that they had won the War for Africa. They were aided and abetted in the propaganda war by the South African government which remained reluctant to come clean about the fighting and which shrank from the task of fully explaining the complex justifications for SADF involvement in Angola.

The Cubans and their Eastern Bloc allies no doubt found it interesting to analyse just which countries theoretically honouring the international arms embargo against Pretoria had helped develop the Olifant’s classified advanced electronics and its modern fire-control system incorporating a laser range finder.

The loss of the Olifants was a classic example of one of the major blemishes of the SADF campaign – the failure of the generals, whether or not because of political pressure, to respect fundamental SADF doctrine that battlefield initiative should rest with the field commanders free from interference by higher officers. It was failure to respect this doctrine, and not any failure of the fighting men, that delivered South Africa’s Olifants to its enemies.

All attempts at displacing Fapla and the Cubans from the last postage stamp of land on the east bank of the Cuito River had failed. With some 800 Cuban troops now dug in around Cuito Cuanavale, even the SADF high command was finally convinced that it was impossible to destroy the enemy bridgehead from the east without a massive increase in South African forces and the loss of hundreds of South African lives. Such a high death toll would of itself have been politically unacceptable in the Republic. But it was out of the question for another reason also – the first round of formal peace talks between Cuba, South Africa and Angola was imminent, and General Jannie Geldenhuys had been appointed a member of his country’s official negotiating team.

The government and the State Security Council decided to demobilise the Citizen Force units of 82 SA Brigade which had been formed for the Tumpo Three battle. Under the Defence Act, no Citizen Force soldier could be compelled to serve for more than 120 days in each two-year cycle. Since the emphasis now was to be on maintaining the status quo, this could be achieved with a reduced body of Permanent Force soldiers abetted by national servicemen units.

‘From the end of April we kept only a very small force of about 1,000 men in southeast Angola to stop any enemy build-up on the east bank of the Cuito,’ said Colonel Deon Ferreira. ‘Tumpo Three was our last offensive effort in that war theatre. Our forces worked until the end of August (1988) laying a massive minefield between the Cuatir and the Chambinga Rivers to keep the enemy pinned down at Tumpo.’

Sapper teams from 13 Field Engineer Regiment and, later, 24 Field Engineer Squadron had the task of laying thousands of anti-tank and antipersonnel mines over a period of nearly five months. It was dangerous work. Major Piet Kock, the commander of 24 Field Squadron, lost his foot when he trod on a Soviet POM-Z anti-personnel Stakemine. POM-Zs, mounted on wooden spikes driven into the ground, have been sown so liberally across the face of Angola by Fapla and SWAPO that peasants and their children will be losing their feet and legs to them well into the next century.

The death of a sapper when detonating a booby-trapped POM-Z led to perhaps the greatest act of courage by an SADF man in the whole War for Africa. A team from 13 Field Regiment was laying and arming a defensive minefield south of the Tumpo River on 23 April 1988 when there was a violent explosion. Four South African engineers and seven UNITA soldiers were scythed down.

Sapper Johannes Jacobus Badenhorst, who was working with another team, walked towards the stricken men even though he had not worked in that part of the minefield and knew nothing about the pattern in which devices had been sown. He carried out one severely wounded man and then walked back to fetch another, who proved to be dead. For more than an hour Sapper Badenhorst worked on defusing mines which surrounded the dead man. He then walked out of the minefield to fetch a ground-sheet, and went back again to wrap the body and carry it out.

The following day Sapper Badenhorst was one of a party of engineers being taken back by a Ratel to the 13 Field Regiment base east of the Chambinga High Ground when the vehicle’s engine caught fire. All the sappers, except Badenhorst, abandoned the vehicle when it became clear the fire was out of control.

Badenhorst stayed aboard the Ratel, loaded with weapons and ammunition, throwing off mortar bombs, R-4 rifles and other equipment until rifle bullets, discharged by the heat, began flying around and drove him out. Badenhorst was treated for severe burns on his hands and was cited by his commanding officer for an ‘extraordinary deed of bravery in the face of mortal danger’. He later received the highest decoration awarded for valour during the War for Africa, the Honoris Crux Silver. Badenhorst’s Silver was the only one given, although 21 slightly lesser ranking Honoris Cruxes were awarded.

The sowing of the minefield began in mid-April. Its pattern was to be roughly horseshoe in shape – beginning south of the Tumpo River; stretching eastwards north of the Chambinga; turning northwards along the eastern edge of the Chambinga High Ground; and turning westwards once more between the Dala and Cuatir Rivers. The intent was to prevent Fapla from pushing eastwards again during 1988 as the SADF wound down its presence in southeast Angola and trained UNITA teams in the use of the vast quantities of weaponry captured during the War for Africa.

The South African sappers laid mainly Armscor R2M1 anti-personnel and No.8 anti-tank mines, but also used Soviet mines captured during the war or dug up from Fapla minefields. In one outstanding operation UNITA’s sappers recovered more than 600 Fapla-sown Soviet TM-57 anti-tank mines and gave them to the South Africans for re-laying against Fapla. Mines were also laid outside the horseshoe along the eastern banks of the Cuito and Cuanavale Rivers where UNITA and SADF thought Fapla might attempt crossings.

Operation Packer formally ended on 30 April 1988 with the departure of Paul Fouché and the demobilisation of the Citizen Force units which had served in his 82 SA Brigade. The new phase, christened Operation Displace, featured scarcely 1,000 troops compared with the 3,000 SADF personnel who were in southeast Angola at the height of the fighting. However, the new force endeavoured by a variety of actions to give Fapla the impression that the SADF was still there in strength.

All the radio nets of the departed units were kept open and very active as part of the deception exercise. Dummy targets were built for Fapla Migs to bomb. Vehicle movements similar in pattern to and as intense as those of 82 SA Brigade were simulated. Ratel training exercises were carried out in such a way as to give the impression that a new armoured attack was being prepared. During one such exercise, on 3 July, the Ratels drew heavy enemy artillery fire as they moved across open ground. One man was killed by shrapnel. He was the final SADF casualty in the southeastern theatre of the War for Africa.

One battery of G-5s, the SADF stars of the war, was brought back to strength and continued a barrage against Fapla targets for months after the men of 82 SA Brigade were back at their desks in insurance offices and behind the wheels of farm tractors.

Peter Honey, southern Africa correspondent of the Baltimore Sun, visited a forward UNITA position on high ground overlooking Cuito Cuanavale and described how the shells from the South African G-5s were still going into Cuito Cuanavale in April 1988 at the rate of about 20 per hour: ‘Binoculars draw closer the stark vista below; scorched craters gaping across the countryside and in the town itself. Only the water tower and a few houses on the northern edge of town seem relatively intact. To the west the airstrip, a vital factor in this protracted siege, seems pocked and scarred with shell holes, although from ten kilometres out it is difficult to assess the damage.’2

The key components of the small Operation Displace team were a squadron of anti-tank Ratel-90s and Ratel-ZT3s led by 32 Battalion’s Major Hannes Nortmann; a multi-racial battalion of motorised infantry of the South West African Territorial Force; a company of trackers from the 201 Bushman Battalion; the sapper teams; and one battery of eight G-5 guns and an MRL battery, operated by both Permanent Force and national service artillerymen.

UNITA deployed three of its battalions to the east of the Tumpo Triangle, with the job of observing the enemy and stopping Fapla reconnaissance patrols from moving beyond the Anhara Lipanda.

1 In fact, the main cause of the G-5 shortage was more likely its export popularity. Armscor had big export orders to fulfil, including an order from Iraq for some 100 G-5s and thousands of tonnes of ammunition.

2 Peter Honey, ‘Siege keeps Angola town in never-ending nightmare’, The Baltimore Sun (Sunday 24 April 1988).