AppleScript, because it is implemented at system level, is omnipresent. Nevertheless, you do not use AppleScript at just any time and any place. AppleScript, like Archimedes' lever, may permit you to move the earth; but first, like Archimedes, you need a place to stand.

The various contexts and milieus in which AppleScript code can be executed may be conveniently grouped into a few general categories; this chapter presents these categories, along with some examples. In other words, this chapter describes the main places where you can use AppleScript. You'll discover that AppleScript is lurking, ready and at your command, in many corners of your computer.

The taxonomy presented here is somewhat artificial, and my names for the various kinds of context in which AppleScript can be used are mostly made up, but I don't think this makes the discussion any less useful. Bear in mind that the example scripts in this chapter are for the most part deliberately simple and contrived; the emphasis here is not on actual uses for AppleScript (as described in Chapter 1), but on places from which you can put it to use.

A script editor is an application such as Apple's own Script Editor (located in /Applications/AppleScript)—a general development environment where the user can create, edit, test, and run AppleScript code. A script editor application will almost certainly be central to your experience of AppleScript. Although you may use AppleScript code in other contexts, those contexts will generally provide no facilities for working on that code. Thus, no matter where you intend to use your code, you will first develop it in a script editor; if you wish to use it in some other context, you'll transfer it to that context from the script editor when you are satisfied that it is ready. If, using it in that other context, you discover there's a problem with it, you'll probably bring the code back into your script editor to test and improve it.

A script editor application will usually allow you to do things such as the following:

Edit a script in a convenient interface

Display a scriptable application's dictionary, which describes how to talk to it with AppleScript

Record user actions in AppleScript form, if a scriptable application is recordable

Compile a script, and display the compiled script in pretty-printed format (compilation is a necessary intermediate step between editing and running AppleScript code, and functions as an initial check on that code's validity)

Run the script's code

View the result, if any, of running the script's code

Save the script in any of the standard AppleScript formats

(Technical terms in this list are formally introduced in Chapter 3.)

There are three main candidates for use as a script editor: Apple's Script Editor , the freeware Smile, and the commercial Script Debugger. Each has its own advantages and peculiarities. You needn't feel confined to any single script editor; compiled scripts are a standard format, so any script editor can read the files of any other. (As of this writing, however, Smile still can't deal with bundle-formatted scripts.)

Warning

Using the AppleScript Utility application, located in /Applications/AppleScript, you can specify a default script editor application—the application that will open compiled script files when they are double-clicked from the Finder.

There are two hazards. First, the presence of Classic interferes somewhat; if anything but Script Editor is made the default editor, Script Editor files may try to open with the Classic Script Editor. Second, and more important, the distinction between files created by the different script editor applications is effectively destroyed; for example, if you use AppleScript Utility to set Script Editor as the default script editor, then a compiled script file subsequently created with Script Debugger may open in Script Editor when double-clicked.

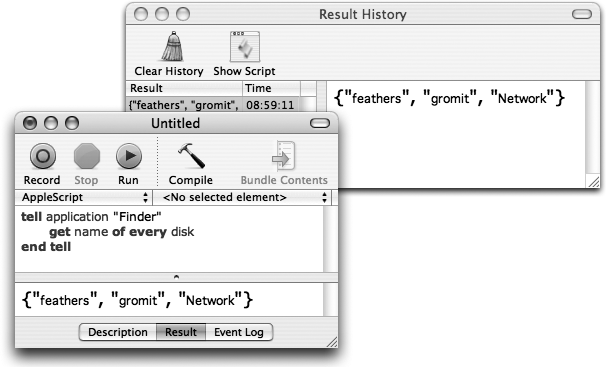

Figure 2-1 shows a very short script being edited in Apple's Script Editor. The script has been compiled using the Compile button, which appears at the center of the toolbar at the top of the window; thus the script is pretty-printed with nice formatting and syntax coloring. The script has also been run, using the Run button in the toolbar; the result is shown in the lower half of the window. The script asks the Finder for the names of all mounted volumes; the response is a list of strings (see Chapter 13). Also shown is the Result History window, which logs the result of every execution of every script.

The lower pane of the script window consists of three tabs. The first tab, Description, lets the user enter a comment to be stored with the script. The second tab, the Result tab, is showing in Figure 2-1. The third tab, Event Log , records all outgoing commands and incoming replies—that is, of all lines of AppleScript that equate to Apple events sent to other applications, and the responses returned by those applications. The Event Log is operative only if the Event Log tab is selected when a script is run; but another window (not shown), the Event Log History window, can be set to operate even when it is not open. Both the Event Log History window and the Result History window are particularly useful while developing and testing a script.

The Script Editor includes some facilities for helping you navigate and edit your scripts. At the top of the window, at the right side below the toolbar, is a popup menu for navigating among handlers (subroutines) within the script. The contextual menu that appears when you Control-click in the window gives access to various utility scripts that drive Script Editor itself (which is scriptable) to modify the text in useful ways. (You can edit these scripts, or add utility scripts of your own; they live in /Library/Scripts/Script Editor Scripts.) When the Script Assistant feature is turned on (in Script Editor's preferences), text is autocompleted as you type; press the Esc key to view or accept an offered completion.

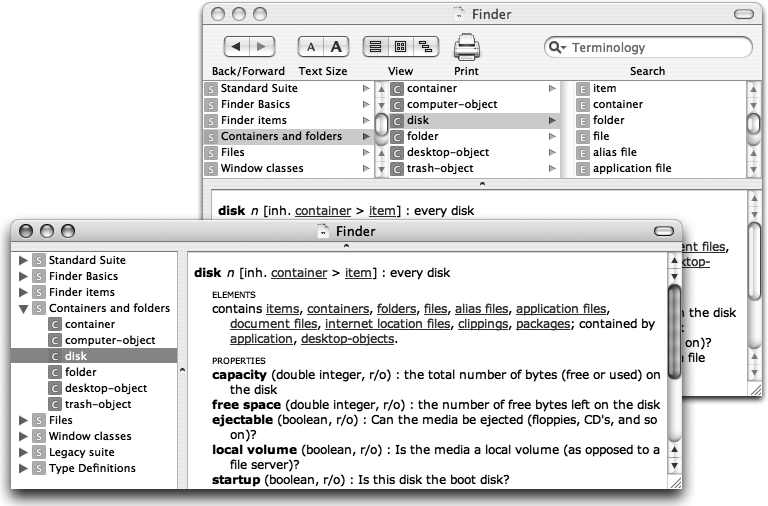

Figure 2-2 shows an application's dictionary as displayed by the Script Editor. A dictionary contains (among other things) classes clumped into groups called "suites"; the dictionary window lets you navigate the resulting hierarchy. The figure illustrates two available navigation modes: you can use an outline at the left (front window) or a browser at the top (rear window). Here, the information for the disk class is being retrieved. Hyperlinks, a Back/Foward button in the toolbar similar to that of a web browser (rear window), and a Search field assist with navigation. The segmented button in the toolbar (rear window, left of the Print button) lets you display two further hierarchies in the browser: the containment chain (object model) and the inheritance chain.

Another free script editor application is Satimage's Smile. It provides an excellent working environment, including fine text-editing and navigation facilities, full scriptability, and some remarkable features to help you in developing scripts, including:

Execution of selected text

Automatic persistence of variables and readily accessible global context

Translation to raw four-letter codes (see Chapter 20)

Display of AppleScript's own dictionary (see Chapter 20)

Global terminology searching

Integrated facilities for constructing custom dialogs and displaying graphics

A third alternative is Late Night Software's Script Debugger . This is a commercial program, but its features can easily justify the price if you're planning on doing any serious AppleScript development; this book could not have been written without it. Among other things, Script Debugger provides:

Display of script-level entity values

Display of values and Apple events in several formats, with browser windows for analyzing complex datatypes

Code coverage indication and timings

Debugging facilities such as breakpoints, stepping, tracing, and expressions

Superior dictionary display, with incorporation of inherited attributes, graphical class charts, and extensive cross-referencing

Display of actual attributes of running applications

Figure 2-3 shows a script paused at a breakpoint in debug mode in Script Debugger (Version 4). The column at the left shows the line where we are currently paused—actually two lines, because we are paused while a handler is being called—with lines that have been executed shaded blue (code coverage). The drawer at the right displays the datatype and value of the most recently executed statement, the handler call stack, and the values of all variables and top-level entities currently in scope (including AppleScript's own properties—see Chapter 16). A complex datatype (a list) is shown in hierarchical format, with icons indicating the owner of object references.

Figure 2-4 shows Script Debugger's unique Explorer view, displaying the hierarchy of actual current Finder objects. The Finder's disk objects are listed among its top-level elements, and the listing for the first disk object has been opened further, drilling down the hierarchy two additional levels. The code needed to refer to the currenly selected object is displayed at the bottom of the window. At the right, a drawer charts the containment hierarchy in graphical form. This concrete display of a scriptable application's actual objects at a given moment is a very instructive and helpful means to understanding the repertory of things one can say to it.