CHAPTER 3

TITANS, PLUTOCRATS, AND PHILANTHROPISTS

By 1859, the United States was disintegrating. Not that William Tecumseh Sherman was thinking much about this. His immediate problem was the need for a job. Since he had left the U.S. Army in 1853, his life had drifted. He struggled and failed as a bank manager. He turned to the practice of law and lost more cases than he won. So, when his old comrade-at-arms Major Don Carlos Buell told him a position was open as superintendent of the spanking-new Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy in Pineville, Louisiana—set to open its doors on January 2, 1860—Sherman seized on it.

And everything started to go swimmingly at last. An Ohioan by birth and upbringing, Sherman nevertheless quickly adjusted to the new climate, surroundings, and people. At forty, when men of substance have already built comfortable lives, Sherman was just beginning to sense the prospect of financial stability. So, on Christmas Eve 1860, Superintendent Sherman was enjoying a collegial dinner with the institution’s professor of classics—until a sharp knock on the door interrupted the two men. It was big news. The state of South Carolina had just proclaimed its secession from the United States of America.

Sherman fixed wide, angry eyes on his dinner companion, David Boyd (future Confederate general and future president of what the Pineville institution would become, Louisiana State University) and said: “This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization!”1

There is no account of how the other man responded when Sherman pressed on: “You people”—and by this, he meant Southern people—“speak so lightly of war; you don’t know what you’re talking about. War is a terrible thing!” He pointed out most specifically that the South lacked the “men and appliances of war to contend against” the people of the North. “The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth—right at your doors. You are bound to fail. … If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.”

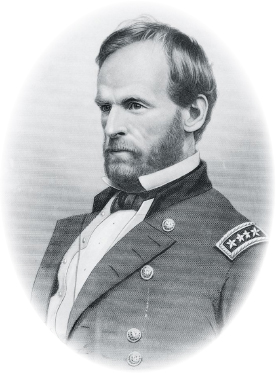

William Tecumseh Sherman, c. 1869.

Sherman would be proved right—mostly, but not completely. The South had men who were not only willing to fight but who were also very good at it. There just weren’t enough of them. The region also had manufacturing, just not nearly enough of it. In the years before the war, South Carolina senator James Henry Hammond famously pronounced cotton “king of the South.” And so it was. “King Cotton” claimed but a modest portion of farmland in southern North Carolina, but held sway over a broad swath in South Carolina and ate up most of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Nearly a quarter of the arable land in Tennessee was devoted to cotton, as was half of Arkansas farmland, a good deal of upper Louisiana, and most of the eastern half of Texas. The Florida panhandle was dotted with cotton plantations as well. A distant second behind cotton were three more cash crops: rice, tobacco, and sugar.

The South’s principal source of wealth, “King Cotton,” was planted, harvested, and processed by slave labor. Without slaves, King Cotton would have been a pauper. This illustration is from the Boston periodical Ballou’s Pictorial, 1858.

Cotton made the South’s slave-owning planters wealthy, some fabulously so. They went about agriculture very differently from Northern farmers. Producers of food commodities, such as wheat, corn, and beef, the Northerners invested in farm machinery to facilitate production. The Southern planters put their money into more and more slave labor. By 1860, the average Northern farmer owned $0.89 worth of farm machinery per acre, whereas the average Southern plantation owner had just $0.42 worth. In the South, the demand for slaves drove up their price dramatically, making slave labor increasingly inefficient in terms of production costs. Northern mechanization, by contrast, made Northern farming highly efficient, which meant that the farmland of that region was more productive. This increased its value even more. On average, an acre of farmland was worth $25.67 in the North, but less than half that in the South, $10.40.2

Some in the South sounded the alarm, calling on planters to diversify investment to include mining, manufacturing, and railroad building. But the planters were loath to abandon what was for them—if not for the region—a very good thing. And so the South, a net exporter of the major slave crops, remained a net importer of manufactured goods during the years before the war. The North, in the meantime, made huge investments in industry, steamship transportation, railroads, and all the financial infrastructure that went with these things—banks, insurance companies, and speculative investment firms. Of the 1,642 banks and bank branches in the United States in 1860, 1,421—86.6 percent—were in the Northern states.3

As of 1860, the United States rail network consisted of 30,626 miles (49,277 km) of track, two-thirds of it in the North, even though the geographical area of the South exceeded that of the North by some 300,000 square miles (777,000 km2). In that same census year, the South reported having roughly 18,000 manufacturing establishments employing 111,000 workers (white men mostly, since slaves were rarely employed in manufacturing), whereas the North had 111,000 manufacturing plants, employing 1.3 million workers. In other words, about 90 percent of the nation’s manufacturing in 1860 came from the North, which entered the Civil War with a far more powerful industrial economy than the South.4

The South had the passion for a fight, but the North had the industry, the railroads, the massive population, and the financial resources to sustain any fight the South might bring. This watercolor by James Fuller Queen, c. 1857, depicts a Pennsylvania factory.

This print, published in Philadelphia shortly after the surrender of Fort Sumter in 1861, depicts the goddess of Liberty descending into the darkness of discord—a prediction of ultimate Union triumph.

For the North, this was a good thing, since the Civil War, which quickly developed into a conflict far larger and far more terrible than anyone (except perhaps William Tecumseh Sherman) had imagined, ran on the output of industrial technology. The North manufactured thirty-two times more firearms than the South—3,200 pieces to every 100 produced in the South. Although cotton was unquestionably king in the South, the North manufactured seventeen times more cotton and woolen textiles and thirty times more leather goods. This translated into uniforms, tents, haversacks, and army shoes—as well as goods for sale. Northern mills turned out twenty times more pig iron than the South—pig iron for railroad tracks, for artillery, and for ammunition.5

“The Civil War created conditions ripe for peacetime industrial expansion.”

So, the Civil War taught Americans a great deal about the power of finance and industry, and the war—mostly—stimulated the expansion of industrial capacity, at least in the North. Shoes and other leather goods underwent spectacular growth during the conflict, as did industries related to arms, ammunition, and the manufacture of wagons. Iron production actually slumped at the outset of the war, but exploded during 1863–64, rising to a level of production 29 percent higher than the nation’s prewar record year of 1856. In mining, coal boomed, with production during 1861–65 rising 21 percent over that of the previous four years. It is true that the devastation of the South’s cotton production hurt the North’s textile manufacturing industry—but only in the area of cotton fabrics. The region’s woolen industry soared some 100 percent in terms of production during the war.6

Of even greater importance than the rise in some areas of industrial productivity was the way in which the demands of war stimulated innovation and invention. Whereas some of the war’s production demands did not outlast the duration of the conflict, the demand for new products and technologies never waned. Enduring wartime innovations included advances in machine-made interchangeable parts for manufacturing; the commercial development of Gail Borden’s “condensed-milk” (patented in 1856), which became an indispensable ration item for Union troops; and improved weapons of all kinds. But dedicated wartime production also created pent-up demand for manufactured consumer goods, which stimulated industrial production and expansion after the war. During the conflict, the production of pig iron rose 10 percent, whereas from 1865 to 1870, the five years immediately following the war, the increase was 100 percent. During the war, output of American commodities increased 22 percent, but rose to a 62 percent growth rate during the postwar 1870s. The war also created pent-up demand for labor by discouraging immigration during 1861–65.7

In short, the Civil War created conditions ripe for peacetime industrial expansion. This was aided by postwar reduction in government regulation, a strong desire among soldiers-turned-civilians to make good lives for themselves and their families, a movement from farm to city, and a general channeling of energies from making war to making products. All these impulses boded well for the American economy; however, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln imparted a far less wholesome quality to the postwar expansion. Lincoln combined pragmatism with idealism to a degree matched by few political leaders before him or since. He committed the Union to total victory, yet he advocated a policy of Reconstruction designed to welcome the South back to the nation. His death meant that his enlightened leniency toward the former Confederacy was abruptly ended, and Reconstruction became the province of Radical Republicans intent on punishing the South and holding it in perpetual economic thrall to the North. As a result, postwar industrial growth and investment were concentrated in the North, and the South became a political pawn that acquiesced in political corruption on a grand scale. The failure of Reconstruction transformed the South into a region of racial oppression, which prompted many African Americans to migrate to the urban North and to laboring and industrial employment. The creation of a laboring underclass not only became a fixture of the Gilded Age, it also took on a racial cast.

In the years following the Civil War, many African Americans migrated from the former Confederacy to the North, with its promise of better treatment and more plentiful and lucrative employment. In this illustration from 1879, hopeful migrants board a riverboat leaving Vicksburg, Mississippi, bound northward.

The Lincoln assassination had another impact on the nature of the Gilded Age. Lincoln the pragmatist did not hesitate to make bargains with profiteers and spoilsmen to advance the cause of victory during the war. He freely ventured into what today would be called crony capitalism. It was clear that such deal making was an expedient intended to win the war and that, come victory, Lincoln the idealist would have likely eclipsed his pragmatism. Of course, we can never know this for certain, but we do know that the absence of a strong and idealistic chief executive after 1865 and before the ascension of Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency in 1901 contributed to the unchecked rise of industrial capitalism under the regime of the robber barons. For all the glories of the Gilded Age, the period was marked by racial oppression—of African Americans, Native Americans, and others—by the devaluation of labor and the rise of industrial slums, and by the development of enormous income inequality. Moreover, while the period saw much economic growth—from which all classes benefited, albeit very unequally—it also endured two catastrophic depressions, one beginning in 1873 and the next in 1893, which caused profound social and political upheaval.

BARONS AND CAPTAINS

The makers of the Gilded Age got their start before the Civil War, but it was in the overheated post–Civil War social, economic, and industrial environment that the makers of the Gilded Age emerged. Both before and after the war, some celebrated them as “captains of industry,” using a phrase that had been coined by the Scottish essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle in his 1843 book Past and Present: “The Leaders of Industry … are virtually the Captains of the World. … [I]f there be no nobleness in them, there will never be an Aristocracy more. … Captains of Industry are the true Fighters … Fighters against Chaos … and all Heaven and all Earth [say to them] audibly, Well-done!”8

However, not everyone saw them in so romantic and idealistic a light. On February 9, 1859, Henry J. Raymond, editor of the New York Times, wrote an editorial titled “Your Money or Your Line.” It blasted Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose fabulous fortune was built on railroading and waterborne shipping—inland steamboats and seagoing steamships, a big enough fleet to earn him the nickname “Commodore Vanderbilt.” Raymond detailed how Vanderbilt extorted large monthly payments from the Pacific Mail Steamship Company in return for his pledge not to compete in the California shipping business. He likened Vanderbilt to “those old German barons who, from their eyries along the Rhine, swooped down upon the commerce of the noble river and wrung tribute from every passenger that floated by.” Raymond’s comparison was to medieval German feudal bandits or “robber knights,” called Raubritter by an early nineteenth-century German writer. After Raymond’s article appeared, the term “robber baron,” a loose English translation of the German word, caught on as a pejorative alternative to “captain of industry.”9 The epithet caught on and was broadly applied to an array of industrialists, financiers, and tycoons.

In this 1883 cartoon, the fat robber barons sit on piles of money and stacks of goods carried safely across the rough seas of “Hard Times” on the bent backs of the laboring masses.

Whether you called them captains of industry or robber barons, their ascension, as a class of businessman, began with the railroads. After the Civil War, the American West offered huge vistas of unlimited wealth. Out there were ores: silver, gold, copper, and iron. The industrial machines needed to mine them were manufactured back East. Out there were cattle and wheat enough to feed even the millions of new factory workers back East who made those machines. The need, therefore, was to connect West with East. Those who did this could make their fortunes. So, railroads—acquiring the land for them, building them, and running them—became the first big business of the Gilded Age, the business that spawned the others.

Railroad magnates not only needed land; they needed laborers hungry enough to break their backs laying the tracks on that land. Making the tracks, first of iron and then of steel, was work for many other hungry men. Getting the land and hiring the men required money, and lots of it. As noted in the Introduction, the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, enacted under Abraham Lincoln, had supplied some of the money and some of the land, but it was in the corrupt climate of the Ulysses S. Grant administration (1869–77) that seemingly endless grants of cash and land were distributed. From across the Pacific came much-maligned and ostracized Chinese immigrants for whom railroading offered at least a chance to keep from starving. From across the Atlantic and the urban slums of the American East Coast came millions of Irishmen, eager for work of any kind. Loaded with land and flush with cash, the railroading robber barons had plenty of work to offer.

From 1868 to 1869, Cornelius Vanderbilt and James Fisk battled one another for control of the Erie Railroad and, with it, a monopoly of rail transportation in New York State. Vanderbilt sought to add the Erie to the two railroads he already controlled, the Hudson River and the New York Central, as shown here in this Currier & Ives cartoon of c. 1870.

The train whistle was to early Gilded Age capitalism what the bugle call was to a cavalry charge. Everywhere, from the Mississippi to the Pacific, Eastern-built locomotives running on Eastern coal pulled more and more parts of the nation westward. For the rest of the nineteenth century, trains dominated the American imagination, politics, and livelihood.

“Everywhere, from the Mississippi to the Pacific, Eastern-built locomotives running on Eastern coal pulled more and more parts of the nation westward. For the rest of the nineteenth century, trains dominated the American imagination, politics, and livelihood.”

In this environment of corruption, energy, and innovation, the likes of Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt, J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and others built their empires and made their fortunes. In the name of efficiency, the industrialists among them introduced large-scale, specialized production in the place of earlier, decentralized methods and practiced “vertical integration,” controlling not merely the manufacture and sale of a final product but also the raw resources the product required. The financiers among the group made massive loans that enabled industrialists to assemble massive trusts, or corporate conglomerates.

In truth, one observer’s captain was another’s robber. Even to this day, to some, the names of many of the following men are infamous. And yet they drove the building of modern America, the nation that created the Gilded Age that took the nineteenth century into the twentieth, the era many would call the “American Century”:

A Currier & Ives print, titled “American Railroad Scene,” 1874. The Gilded Age was the first great epoch of American railroading. Rail transportation tamed both time and distance, making it the foundational technology and industry of the last third of the nineteenth century.

ANDREW CARNEGIE, steel magnate of Pittsburgh and New York

WILLIAM A. CLARK, copper king of Butte, Montana

JAY COOKE, Philadelphia-based financier

CHARLES CROCKER, railroad magnate of San Francisco

JAMES BUCHANAN DUKE, tobacco prince, Durham, North Carolina

MARSHALL FIELD, Chicago’s genius of retail commerce

JAMES FISK, New York-based financier

HENRY MORRISON FLAGLER, oil, railroad, and real estate empire builder in New York and Florida

HENRY CLAY FRICK, steel magnate of Pittsburgh and New York

JAY GOULD, leading railroad developer and speculator, New York

EDWARD HENRY HARRIMAN, railroad magnate from New York

JAMES J. HILL, St. Paul–based fuel, coal, steamboat, and railroad magnate

MARK HOPKINS, railroad financier from California

COLLIS POTTER HUNTINGTON, California and West Virginia railroad man

ANDREW W. MELLON, financier and oilman, Pittsburgh

J. P. MORGAN, New York-based financier and industrial consolidator

HENRY B. PLANT, Florida railroad man

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, founder of Standard Oil, based in Cleveland and New York

CHARLES M. SCHWAB, steel man, Pittsburgh and New York

JOSEPH SELIGMAN, New York banker

LELAND STANFORD, railroad tycoon from California

CORNELIUS VANDERBILT, railroad and shipping tycoon, New York

CHARLES TYSON YERKES, builder of street railways in Chicago

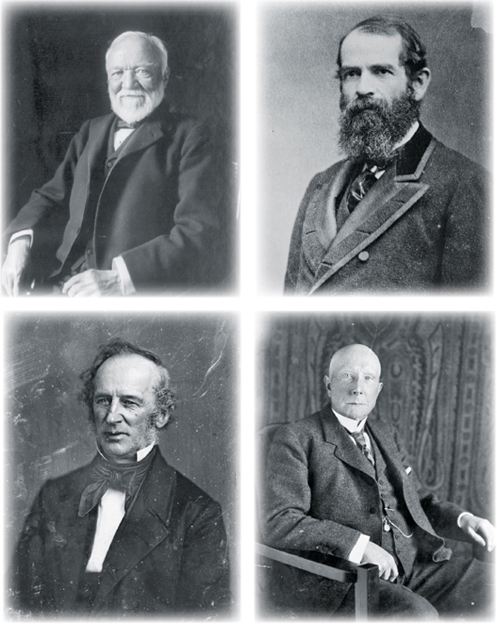

Titans of the Gilded Age, clockwise from top left: Andrew Carnegie, c. 1913; Jay Gould, c. 1880; John D. Rockefeller, c. 1909; Cornelius Vanderbilt, c. 1860.

In their own time, bombastic apologists dubbed them industrial “statesmen” for enhancing and modernizing the American capitalist system, while strident detractors pointed to their indifference to public welfare and their ostentatious displays of wealth at the expense of their workers—living in huge mansions while their employees languished in urban squalor or bleak company towns. The reigning philosophy was summed up neatly in the phrase for which William Vanderbilt became infamous: “The public be damned!”

Surely this had seemed the attitude of William Vanderbilt’s father, “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, who relentlessly built the New York Central into the largest single railroad line in America. Mark Twain, who thought him both rapacious and vulgar, excoriated him in an “Open Letter” published in the March 1869 edition of Packard’s Monthly: “Most men have at least a few friends, whose devotion is a comfort and a solace to them, but you seem to be the idol of only a crawling swarm of small souls, who love to glorify your most flagrant unworthiness in print; or praise your vast possessions worshippingly; or sing of your unimportant private habits and sayings and doings, as if your millions gave them dignity.”10

“The public be damned!” likewise described Jay Gould’s attitude when he had used an unwitting President Grant in a scheme to manipulate the gold market in 1869 by indirectly persuading the president to suspend gold sales. Under Grant, the U.S. Treasury sold a set amount of gold each week to pay off the national debt—a heavy burden after the Civil War—and to stabilize the dollar. With his business partner James Fisk, Gould persuaded Abel Corbin, a financial speculator married to the president’s sister, to introduce them to Grant so that they could obtain inside information on the gold sales, which would allow them to manipulate and corner the gold market. Gould convinced Grant that the gold sales were hurting Western farmers. Grant instructed Secretary of the Treasury George S. Boutwell to suspend sales, whereupon Gould and Fisk bought up all the gold they could lay their hands on, thereby driving up its price. Made aware of the manipulation, Grant ordered $4 million in gold to be released on Friday, September 24, 1869. Gould was foiled in his effort to corner the market, but Wall Street panicked and the gold and other financial markets crashed. It was dubbed Black Friday. In this crisis, the railroads—already ripe for disaster as a result of intense competition and a shaky economy—rather than go bankrupt, sold out to war profiteer J. P. Morgan. Morgan, who by 1900 would own half of all railroad track in America (his friends owned the rest), set exorbitant shipping rates across the country. His massive fortune grew even more massive.

John Pierpont Morgan—shown here at center, in a photograph from c. 1907—emerged from the Gilded Age as the archetypal American financier and banker, the dominant force in corporate finance as the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth.

It was Morgan who, in 1901, established United States Steel Corporation, to which Andrew Carnegie sold Carnegie Steel that year for $480 million (close to $13 billion in today’s dollars). Confident that his steel company would be the core of a great vertical trust that would control every aspect of steel making, Carnegie had mocked Morgan’s Federal Steel as “the greatest concern the world ever saw for manufacturing stock certificates,” but predicted it “will fail sadly in Steel.” In fact, Federal rapidly closed in on Carnegie Steel, whereupon Charles Schwab, Carnegie’s number-two man and an unabashed advocate of business by monopoly, covertly met with Morgan to discuss selling him Carnegie Steel. Finding interest, Schwab next rendezvoused with Carnegie, who was golfing at the St. Andrews Golf Club in Westchester County, New York. The magnate finished his game, went home, slept on the matter, summoned Schwab, and handed him a slip of paper on which he had written “$480 million,” his selling price. Schwab took the slip to Morgan, who said, “I accept this price.” With that, U.S. Steel was born, and Andrew Carnegie became the richest man in the world.11

ANDREW CARNEGIE: BOBBIN BOY MAKES GOOD

Of all the men of business most closely associated with the Gilded Age, no one is more iconic than Andrew Carnegie. He was born in 1835, far from anything gilded, in a small weaver’s cottage in the Scottish town of Dunfermline. The year after his birth, the family moved to a larger house, thanks to a bump in the senior Carnegie’s income earned as a weaver of heavy damask, suddenly much in demand for upscale upholstery and drapery. Andrew came of age in a backwater, but he benefited from a good elementary education in the town’s Free School, the gift of a philanthropist named Adam Rolland. Although Rolland had died years before Andrew was born, Carnegie never forgot that the beginning of everything he knew about the larger world came because of Rolland’s dedication to the public good.

Andrew Carnegie (right) was thirteen when he and his younger brother Thomas were taken by their mother and father from a blighted Scotland, hard hit by the Highland Potato Famine, to the promise of America. The thirteen-year-old found work as a “bobbin boy” in a Pennsylvania cotton mill.

The Highland Potato Famine, a blight that devastated Scottish agriculture beginning in 1846, brought the hardest of hard times when Andrew was thirteen. As the Highland economy collapsed, the demand for damask (and everything else) fell off sharply. Mrs. Carnegie eked out an income as an assistant to her cobbler brother and by selling potted meats. At last, in 1848, the struggling Carnegies, like so many other European families, sought relief through immigration to America. The four Carnegies—father, mother, Andrew, and his younger brother, Thomas—settled near Pittsburgh, where Andrew went to work as a bobbin boy, running from loom to loom in a cotton mill, replacing empty bobbins with full ones. His pay, $1.20 a week, was vital to the support of his family, yet he still found time to devour works of history and literature at the local public library. A quick study, young Carnegie left the mill to become a messenger for the Ohio Telegraph Company, graduating to full-fledged telegraph operator after only a year. Now he became acquainted with a wealthy local businessman, Colonel James Anderson, who gave working boys like Carnegie the run of his impressive personal library. Many years later, Andrew Carnegie would dedicate a considerable part of his fortune to building public libraries in cities and towns across America.

In 1853, Carnegie became telegrapher/secretary for the Pennsylvania Railroad and rapidly rose to the position of superintendent of the Pittsburgh Division. In this position, he soaked up the lessons of managing a large organization, in particular the fine art of cost control. This knowledge would stand him in good stead throughout his career. At thirty, he left the Pennsylvania Railroad to start his own company, Keystone Bridge, which soon expanded from building iron bridges to operating iron and steel mills. In 1872, Carnegie and several investors built Pittsburgh’s first steel mill, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, named after the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Within two decades, Carnegie Steel was the biggest steel maker in the world, and Andrew Carnegie, bobbin boy from Dunfermline, found himself among the world’s wealthiest men.

In 1872, Andrew Carnegie and a group of investors built Pittsburgh’s first steel mill, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works (depicted in this photograph, c. 1908), named after the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. By the early 1890s, Carnegie Steel was biggest steel maker in the world.

It was his sharply honed skill at cost cutting that drove him to the top. Invariably, he managed to underprice and outsell his competitors. But his efficiency came at a cost—to those who worked for him. Carnegie automated certain aspects of steel production, with newly designed overhead cranes to handle materials and with machines to charge his cutting-edge open-hearth furnaces. Although he hired more workers as demand for his steel grew, the modernized production reduced the need for skilled workers. His expanded mills relied chiefly on unskilled labor, from which he ruthlessly extracted every last ounce of effort. Their wages were the lowest in the industry, and Carnegie vigorously fought efforts to reduce his company’s twelve-hour days to eight. It was an extreme example of what was nevertheless typical of late nineteenth-century American industrial labor. Owners willingly worked employees to exhaustion, if not death, and they did not hesitate to fire anyone who complained.

On June 30, 1892, Carnegie workers did more than complain. Since the early 1880s, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (AA) had represented the skilled laborers in mills west of the Allegheny Mountains. After an 1889 strike at the Homestead (Pennsylvania) works, Carnegie and his management team determined that AA work rules inflated costs unacceptably. Moreover, relations between union workers and managers became increasingly belligerent, even toxic. Henry Clay Frick, an industrialist whom Carnegie had put in charge of his steel company’s operations, resolved to break the union once and for all. This put Andrew Carnegie in an acutely uncomfortable position. Having grown up poor in a time and a place that routinely oppressed labor, he had publicly—and sincerely—proclaimed his support for unions. But his passion for efficient production now outweighed every other consideration. In preparation for the strike he knew would come when the current collective bargaining agreement with AA expired, Carnegie ordered a ramp-up of production so that there would be sufficient product on hand to outlast the impact of any work stoppage. The Homestead plant employed 3,800 workers, of whom only 800 were skilled men represented by AA. When the union demanded a wage increase for its 800 members, Carnegie decided to provoke a strike by directing Frick to counter not only with a wage decrease (as much as 22 percent for many men), but also with the elimination of numerous skilled positions.

Strikers keep an eye out for trouble at the Homestead works of the Carnegie Steel Company during the great strike and lockout of 1892.

On April 30, 1892, Frick warned AA leaders that he would continue bargaining for just twenty-nine more days, after which Homestead Steel would cease to recognize the union. In a cynical show of good faith, Frick offered a token improvement in the wage scale, but the union did not back down from its original demands. On June 28, Frick imposed a partial lockout at the Homestead plant. This was followed the next day by a total lockout of union workers.

Homestead Steel became an armed fortress—“Fort Frick” it was dubbed—complete with barbed wire, sniper towers, and water cannon. On their side, the AA men, now reinforced by the huge Knights of Labor union and workers at other Carnegie mills, took steps to close the plant to all workers, skilled and unskilled. With both sides girding for war, Frick hired a private “army” of three hundred Pinkerton guards. This force assembled at the Davis Island Dam on the Ohio River on the night of July 5, 1892. Winchester rifles were distributed to them, and, on July 6, they sailed up the river in two barges. The guards disembarked at the plant, precipitating a pitched battle in which nine strikers and seven guards were killed before the Pinkertons surrendered.

Rioting in and around the town of Homestead continued until July 12, when Pennsylvania governor Robert E. Pattison dispatched eight thousand state militiamen to Homestead. Gradually, the militia quelled the riot, and strikebreakers began working at the plant. Over the next four months, Carnegie Steel lodged formal complaints against about a hundred strikers, many of whom (at the company’s instigation) were arrested on charges of murder. Although most of the charges were subsequently dismissed and no one was convicted, the AA bled its coffers dry on legal defense costs alone, and the strike was officially called off on November 20, 1892. Carnegie Steel emerged victorious, which meant that workers continued to endure twelve-hour days for even lower wages. On the one hand, Homestead had demonstrated to the nation the determination of the labor unions. On the other, it showed that this determination had its limits.

The Homestead strike turned public opinion in two directions. Labor leaders and political reformers saw it as an occasion to condemn an unholy alliance between capital and government, whereas business leaders and many in the middle class condemned it as an instance of an arrogant labor union run amok. Only one thing was certain: the hard line between capital and labor, between big business interests and the masses, had become that much harder, and men like Carnegie were put on the defensive. Four years before the Homestead strike, Carnegie had published in the North American Review an essay titled “Wealth,” in which he acknowledged that the “conditions of human life have not only been changed, but revolutionized, within the past few hundred years. In former days there was little difference between the dwelling, dress, food, and environment of the chief and those of his retainers.” In modern times, however, the difference between high and low was huge. Far from being inequitable, however, Carnegie argued that the “contrast between the palace of the millionaire and the cottage of the laborer with us today measures the change which has come with civilization.” It is, he wrote, a change “not to be deplored, but welcomed as highly beneficial. It is well, nay, essential for the progress of the [human] race that the houses of some should be homes for all that is highest and best in literature and the arts, and for all the refinements of civilization, rather than that none should be so.” There is, however, a price to be paid “for this salutary change” in civilization, and it “is, no doubt, great”:

After homestead strikers and Pinkerton guards hired by Carnegie Steel fought a pitched battle on July 6, 1892, rioting spread to the town of Homestead, prompting Pennsylvania’s governor to call in state militia troops, shown here in a Harper’s Weekly illustration of July 23, 1892.

We assemble thousands of operatives in the factory, and in the mine, of whom the employer can know little or nothing, and to whom he is little better than a myth. All intercourse between them is at an end. Rigid castes are formed, and, as usual, mutual ignorance breeds mutual distrust. Each caste is without sympathy with the other, and ready to credit anything disparaging in regard to it. Under the law of competition, the employer of thousands is forced into the strictest economies, among which the rates paid to labor figure prominently, and often there is friction between the employer and the employed, between capital and labor, between rich and poor. Human society loses homogeneity.

The “law of competition” does create inequality, Carnegie conceded, “and may be sometimes hard for the individual,” but “it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department.”12

“Survival of the fittest” became the rationale many so-called robber barons used to justify the social inequality on which their fortunes were built. This phrase summed up the doctrine of social Darwinism—the transfer of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection (essentially, the survival of the fittest, best-adapted organisms) from the realm of biology to society. In the English-speaking world, the great proponent of social Darwinism was the British biologist/sociologist Herbert Spencer (1820–1903), whose works enjoyed a tremendous vogue during the 1880s and 1890s.

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER AND STANDARD OIL

Perhaps even more emphatically than Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937) unabashedly embodied social Darwinism in business. The American oil industry was born in 1859, when Edwin Drake was hired by the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company to investigate “oil seeps” on company-owned land. In 1859, Drake decided to drill the first commercial oil well along the banks of Oil Creek near Titusville, Pennsylvania. John D. Rockefeller, living in Cleveland, Ohio, took notice. Convinced that there was a great future in petroleum, he decided to get into this new oil business, and figured that his hometown was perfectly situated for building a major oil refinery. By 1862, he was in operation—and the refinery took off right from the start.

But Rockefeller kept looking forward. He envisioned more than a refinery. His ambition was to control all aspects of the oil industry, from extracting the raw materials through pricing and distribution. To that end, he formed a trust, the first and the largest in the country. A “trust” was a corporate conglomerate that put under unified management as many companies as were necessary to achieve end-to-end control of an industry. As Rockefeller saw it, the trust was the corporate organization “fittest” to survive and prosper in modern business. The reason was simple. A monopolistic trust crushed everyone and everything that got in the way of its growth.

A board of nine trustees ran the Standard Oil trust, managing the operations not only of Standard Oil of Ohio but also of the numerous smaller companies across America that Standard Oil gobbled up whole. The trust made ever-larger profits, which allowed Standard to undercut the competition by waging scorched-earth rate wars against them. The bigger the company got, the more power it wielded. Once again, success depended on the railroads. Rockefeller was big enough to demand—and receive—preferential freight rates and rebates from the main lines. He soon moved the headquarters of the trust from Ohio to New York City, where he could better manage relations with the nation’s financial titans and from which he could, through a massive network of information gatherers and analysts, keep his fingers on the pulse of consumers and competitors alike.

The Darwinian rapacity of Rockefeller did not go unchallenged by reformers (see chapter 14), and, using the Sherman Antitrust Act Congress had passed in 1890, President Theodore Roosevelt directed his attorney general to bring suit against the trust with the objective of breaking it up. It was not until 1911, during the administration of Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, that the Supreme Court—responding to a fresh wave of Progressive reforms—determined that Standard Oil was operating in violation of the Sherman legislation by monopolizing an industry and unfairly restraining free trade. The Court handed down a decision that ordered the trust dissolved into thirty-four companies.

John D. Rockefeller, junior and senior, take a stroll in 1910. President Theodore Roosevelt invoked the Sherman Antitrust Act to break up the Standard Oil trust, but it was a Supreme Court decision in 1911, during the administration of William Howard Taft, that finally dissolved the trust into thirty-four companies.

THE GOSPEL OF WEALTH

Many considered robber barons like Rockefeller and Carnegie immoral or amoral or ruthless or just plain evil. Yet these men were hardly deaf to the public outcry against them. In fact, many of them devoted generous portions of their personal and corporate wealth to programs of philanthropy unprecedented in scope and enduring to this day. Such corporate philanthropy became as much a part of the Gilded Age legacy as corporate greed.

Both Rockefeller and Carnegie were among the leaders in nineteenth-century American philanthropy, along with J. P. Morgan, Henry Clay Frick, Leland Stanford, and, in the generation immediately following them, Henry Ford. Carnegie even wrote about it. In “Wealth,” the same 1889 essay in which he defended the material prosperity of the captains of industry on the grounds of necessary and beneficial social Darwinism, Carnegie also proposed that the upper class of self-made millionaires like himself owed an absolute obligation to society to redistribute their surplus wealth not in family bequests, but in thoughtful, socially beneficial philanthropy. In 1901, when the essay was published with other Carnegie writings in book form, its title was expanded from “Wealth” to “The Gospel of Wealth.”13

Rockefeller’s Midas crown, depicted in this 1901 cartoon, illustrates the nature of the vertical monopoly or “combination.” Standard Oil controlled not only the extraction, refining, and sale of oil, but also the very means of its transportation via a network of railroads in which he held majority shares.

“There are but three modes in which surplus wealth can be disposed of,” Carnegie wrote. “It can be left to the families of the decedents; or it can be bequeathed for public purposes; or, finally, it can be administered during their lives by its possessors.” Carnegie rejected the first “mode” as (among other things) “misguided affection” because “great sums bequeathed oftener work more for the injury than for the good of the recipients.” He rejected the second mode, “leaving wealth at death for public uses,” because it required that a person be “content to wait until he is dead before [his wealth] becomes of much good in the world.” Moreover, the “cases are not few in which the real object sought by the testator is not attained, nor are they few in which his real wishes are thwarted. In many cases the bequests are so used as to become only monuments of his folly.” This left the third mode:

This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of Wealth: First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and after doing so to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community—the man of wealth thus becoming the mere agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves.

In this mode of redistributed wealth, Carnegie wrote, “we have the true antidote for the temporary unequal distribution of wealth, the reconciliation of the rich and the poor—a reign of harmony—another ideal, differing, indeed, from that of the Communist in requiring only the further evolution of existing conditions, not the total overthrow of our civilization.” If the wealthy do their duty, “we shall have an ideal state, in which the surplus wealth of the few will become, in the best sense the property of the many, because administered for the common good.” The wealth of the individual, earned by being the fittest, and “passing through the hands of the few,” Carnegie continued,

can be made a much more potent force for the elevation of our race than if it had been distributed in small sums to the people themselves. Even the poorest can be made to see this, and to agree that great sums gathered by some of their fellow-citizens and spent for public purposes, from which the masses reap the principal benefit, are more valuable to them than if scattered among them through the course of many years in trifling amounts. … The laws of accumulation will be left free; the laws of distribution free. Individualism will continue, but the millionaire will be but a trustee for the poor; intrusted for a season with a great part of the increased wealth of the community, but administering it for the community far better than it could or would have done for itself.

“Thus is the problem of Rich and Poor to be solved,” Carnegie triumphantly commenced the conclusion of his essay. Thus, too, is the problem of deciding whether the builders of the Gilded Age—men such as he—were robber barons or captains of industry. Anyone “who dies leaving behind many millions of available wealth, which was his to administer during life, will pass away ‘unwept, unhonored, and unsung,’ no matter to what uses he leaves the dross which he cannot take with him,” Andrew Carnegie wrote. “Of such as these the public verdict will then be: “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

Carnegie’s greatest and most visible legacy to the nation that made him rich is the many public libraries he built and financed in the United States—1,759 in all. In this photograph from c. 1905, children read in the historic Pittsburgh Carnegie Library.