CHAPTER 5

THE MARKETPLACE

The Gilded Age is often portrayed as the era of corporate conglomeration, of relentless mergers and acquisitions, and of monopolistic trusts designed to crush all competition. If this picture is less than accurate, it is only because the situation was often even worse. Companies such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil not only bought up or squeezed out competing oil companies, they adopted so-called vertical growth strategies to acquire everything necessary to control their industry and markets end-to-end. Thus Standard Oil not only engaged in the extraction and refining of oil, it also acquired pipelines, railroad tank cars, and terminal facilities. The company even had a subsidiary that manufactured oil barrels. In 1882, a novel corporate arrangement was established by which Standard Oil stockholders voluntarily transferred their shares to a board of trustees who controlled the entire conglomerate of companies. For this, stockholders received a share of the consolidated earnings of these jointly managed companies. Standard soon became so big that collusion among refineries to regulate output and price became business as usual. A company that defied its price-fixing scheme risked being undercut, bought out (cheap), or simply driven out of business. So successful was the Standard trust that the business model was adopted by big firms in some two hundred American industrial sectors, including sugar, coal, steel, and tobacco.

A Standard Oil stock certificate from 1882, the year in which investors transferred their shares to a board of trustees presiding over a vast “trust,” which controlled Rockefeller’s entire conglomerate of companies. With this move, the vertical monopoly was born.

Certainly, Andrew Carnegie followed Rockefeller’s strategy closely, although his route to transforming Carnegie Steel into a super-corporation took an even craftier, more personal turn that focused more closely on finance than on building verticals to control the market. As the nineteenth century drew to a close, Carnegie, perhaps tired of his perpetual wars with labor, began to think about selling his steel company. He would content himself with no ordinary sale, however.

In 1898, the financier J. P. Morgan absorbed a company called Illinois Steel into the company he controlled, Federal Steel. The enlarged firm then reached out to acquire other, smaller steel companies. Taking note that Morgan was obviously conglomerating, Carnegie decided to offer him his company. He hardly approached the financier hat in hand, however. Instead, Carnegie played his man, as the saying goes, like a grand piano.

Morgan had a well-deserved reputation for rapacity. Among a generation of hyperaggressive capitalists, none were more ravenous than he. That was fine with Carnegie, who used his press agent—the forerunner of a corporate publicity office—to let it be known that he was about to build a mammoth plant for the manufacture of steel pipe and tubing. It would be unprecedented in cost ($12 million) and size—the largest such enterprise in the world. Morgan, as Carnegie well knew, owned a controlling interest in the National Tube Works, with which Carnegie’s proposed enterprise would obviously compete. Leaving nothing to chance, Carnegie next began planting rumors that he was about to build, from scratch, a railroad to carry not only his own steel products to market but those of others as well. He knew, of course, that Morgan happened to own the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Faced with the specter of competition not in one but in two major industries, Morgan grew visibly concerned. That is when Carnegie pounced. Charles M. Schwab began as a laborer in the engineering department of one of Carnegie’s steelworks and rose rapidly through the ranks to become, in 1897, president of Carnegie Steel itself. As chairman of the company, Carnegie directed Schwab to invite Morgan to a dinner party at the University Club in New York on December 12, 1900, and, over an elegant meal, persuade him to buy Carnegie Steel so that Morgan could join it to what he already owned and create the biggest steel company in the world—United States Steel. Morgan took the bait and, the following month, in January 1901, bought out Carnegie for the price of the entire initial bond issue of U.S. Steel—$303.45 million—and a large bloc of preferred and common stock, making a total sale price of $480 million.1

The deal was so big and U.S. Steel itself was so big, that it could not help but become even bigger as investors gobbled up the new company’s stock, driving up the price of common shares from 38 to 55 in scarcely the blink of an eye, with preferred stock exploding from 82¾ to 101⅞.2 For a time, this single stock lifted the entire New York Stock Exchange with it; in 1901, Progressive journalist Ray Stannard Baker wrote that U.S. Steel “receives and expends more money every year than any but the very greatest of the world’s national governments; its debt is larger than that of many of the lesser nations of Europe; it absolutely controls the destinies of a population nearly as large as that of Maryland or Nebraska, and indirectly influences twice that number.”3

By purchasing Carnegie Steel, J. P. Morgan created United States Steel, the biggest steel maker in the world. Already enormously wealthy, he grew mightier than kings and emperors, as illustrated in this Puck cartoon of 1902

EVEN AS MANY IN THE PUBLIC eagerly invested in US Steel, there was growing concern about trusts and other conglomerates. In 1902, The Commoner, a magazine owned by the Populist politician William Jennings Bryan, distilled the substance of this growing discontent by quoting J. P. Morgan himself: “America is good enough for me.” Presumably, Morgan intended this as a benign expression of patriotism, but the editor added his own comment: “Whenever he doesn’t like it, he can give it back to us.”4

The Gilded Age was torn between admiration of big business and resentment, revulsion, and rage. Some corporate behemoths looked for ways to reconcile with the public. As discussed in chapter 3, some tycoons—such as Carnegie and Rockefeller—turned toward philanthropy. This is not to imply that they were insincere. To read Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth” is to be convinced that his passion for philanthropy was genuine. But it is also true that a display of public-spirited philanthropy and good corporate citizenship did much to improve the image of big enterprise, defuse public anger, and thwart any federal regulatory action.

THE TOBACCO DUKES

Other businesses found different ways to win public sympathy. Tobacco had been a tremendously popular consumer product in Europe since the sixteenth century, when Jean Nicot, French ambassador to Portugal, brought tobacco plants—newly introduced to the Iberian Peninsula—to Paris. The use of snuff by the French royal court popularized tobacco throughout the continent and England. As for Nicot, the great Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus named the tobacco plant in his honor, Nicotiana, from which the modern word nicotine is derived.

The Dukes of North Carolina, brothers James “Buck” (left) and Benjamin, launched the American Tobacco Company and then built it into a “tobacco trust” conglomerate.

By the nineteenth century, many Europeans smoked tobacco in the form of hand-rolled cigarettes, a practice that became even more prevalent when large-scale cigarette manufacturing began in France in the 1840s. In the United States, however, cigarettes had a hard time catching on. Smoking them in private was socially questionable for women, and smoking them in public downright indecent. Men, of course, could do as they wished, but cigarette smoking by men was widely deemed effeminate. Pipes, cigars, a good chew—these were manly actions. Cigarettes? A bit too dainty.

The Duke brothers, James “Buck” Buchanan and Benjamin, joined their father, George Washington Duke, in the family cigarette business when it was no more than a North Carolina family business. The Dukes produced so-called ready-mades—hand-rolled cigarettes—in an era when most of those who smoked cigarettes at all rolled their own, using cut tobacco and rolling papers. The ready-mades were a luxury item for the few who could afford them. In 1880, however, a young man from Virginia’s tobacco country, James Albert Bonsack, patented an ingenious cigarette-making machine. It fed very finely shredded tobacco onto a continuous strip of rolling paper, which the machine shaped, rolled, pasted, and cut into individual cigarettes. In 1885, the Dukes bought the machine and put it to work. As they had hoped, bringing down the price of cigarettes through mass production enlarged the market for the product. Believing that they were on the verge of making and marketing a truly major consumer good, the Dukes decided in 1890 to clear the way by buying up several smaller competitors in exchange for stock in the new conglomerate, to be called the American Tobacco Company.

The Bonsack cigarette-making machine was the Gilded Age innovation that enabled the mass production of “readymade” smokes. Freed from the effort of “rolling their own,” smokers turned in droves from pipes, cigars, and chewing tobacco to cigarettes—and American Tobacco owned the most profitable brands.

Now the family had the means to increase production and thereby lower retail cigarette prices even more. They also—for the time being, at least—controlled the market for cigarettes. The only trouble was that the market was still too small. Fortunately for American Tobacco, the Duke brothers were not only innovators in production, they proved to be innovators in marketing. The Dukes took branding beyond trademarking. Understanding that smoking was all about gratifying a personal taste, they created not just one brand, with a unique name and image, but a range of brands, each intended to convey a distinct quality and appeal, and each targeting a particular consumer who had a particular taste in tobacco.

FIRST TRADEMARKS

The concept of the brand—a name, a symbol, a trademark that conveys to the marketplace a product’s unique identity—dates from prehistory, but the first universally recognized trademark still in existence may be the red triangle registered in Britain by the Bass® Brewery on January 1, 1876, ninety-nine years after the brewery was established at Burton-upon-Trent, England. In the United States, in 1870, Congress enacted legislation to codify the so-called Copyright Clause of the Constitution (Article I, Section 8, Clause 8). Amended in 1878, the statute was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1879. In 1881, Congress passed a new Trademark Act based on the Commerce Clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3), and on May 27, 1884, the J. P. Tolman Company became the first U. S. company to formally register its trademark: a depiction of Old Testament strongman Samson, which branded ropes made by the firm. (To this day, the company operates under the 1884 trademark, as Samson® Rope Technologies, Inc.)5

The Dukes not only produced various brands of cigarettes, they ventured into other tobaccos, including pipe and chewing tobacco. The latter was an especially popular category of merchandise, and American Tobacco entered a marketplace so fiercely competitive that consumers and retailers alike referred to “plug wars” among rival tobacco companies. Using a combination of aggressive branding (American Tobacco chewing tobaccos were marketed under such names as Horseshoe and Battle Axe); saturation advertising (including paying farmers to allow the company to paint billboards on the sides of barns); free-sample distribution; aggressive merger and acquisition practices; and predatory pricing that undercut smaller competitors, American Tobacco became the Standard Oil of its industry.

THE ART OF THE BRAND

By the height of the Gilded Age, American Tobacco had hooked Americans on two addictions. The first was to tobacco itself—although the nearly universal adoption of cigarettes would not truly sweep the nation until the end of World War I in 1918. The second, even more enduring habit, was the American addiction to brands. Consumers became “loyal” to certain brands partly because the merchandise was good or effective or priced for value, but mostly because they identified the brand—the identity of the product created through packaging and advertising—as good, effective, or priced right. As standardized mass production in a growing array of industries flooded consumer markets with very similar products, brands were often the only component that distinguished one offering from another.

Branding brought products to national attention, persuading consumers to trust and to purchase a mass-produced, nationally distributed item of merchandise as if it had been made by a local, long-familiar, and personally trusted craftsman. As branding became instrumental in selling products to the largest possible market, so advertising became essential to defining and disseminating the brand. Like branding, advertising dates to earliest recorded history, but the advertising agency—a business dedicated to creating and delivering advertising messages—came into being in London during the late eighteenth century and, in the United States, in 1850, with the founding of Volney B. Palmer’s Philadelphia-based advertising business. In 1869, Francis Ayer founded N. W. Ayer & Son, also in Philadelphia, which is generally acknowledged as the first dedicated, full-service advertising agency.

“As branding became instrumental in selling products to the largest possible market, so advertising became essential to defining and disseminating the brand.”

While N. W. Ayer & Son was growing in Philadelphia, a young man from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, named James Walter Thompson was seeking his fortune in New York City working for Carlton and Smith. Established in 1864, the company specialized in selling advertising space in religious magazines. Its senior partner, William James Carlton, hired the twenty-one-year-old Thompson in 1868 as a bookkeeper, only to discover that his new hire’s real talent lay in selling ad space. Indeed, Thompson soon became the modest firm’s leading salesman. Recognizing that he had become indispensable to the company, Thompson, in 1877, offered to buy out Carlton and Smith. William James Carlton sold it to him for all of $500, along with all the office furniture for an additional $800.6 After changing the name of the company to J. Walter Thompson®, the new owner soon transformed it into the go-to agency for any advertiser who wanted to buy space not just in religious publications, but in almost any periodical or magazine. By 1889, J. Walter Thompson was placing some 80 percent of all print ads in the United States.7 In 1899, the company went international by opening a London office. Today, the firm operates in more than ninety countries and is an icon of the advertising industry.

J. Walter Thompson’s dominance of American advertising during the Gilded Age earned him the enduring title of the “father of advertising.” In addition to Thompson’s own extraordinary talent as a salesman, two other qualities were responsible for the agency’s remarkable development. First, Thompson started providing more than his services as a buyer of space and a placer of ads. He hired writers and illustrators and offered to create the ads he placed for his clients. What he produced was invariably far more compelling and persuasive than anything his clients could put together themselves. From here, Thompson went even further, designing product packaging, conducting market research on their behalf, and, most notably, developing trademarks, which Thompson believed was the very core of creating an effective brand. By 1900, the J. Walter Thompson agency was advertising itself as the master of trademark creation, and in 1911 literally wrote (and published) the book on the subject.8

The pioneering ad agency J. Walter Thompson believed so strongly in advertising that it advertised itself in the Blue Book of Trade Marks and Newspapers in 1889. That year, “80% of the advertising in the United States” was placed by Thompson.

One of the biggest names of the Gilded Age had no need of J. Walter Thompson to convince him of the power of branding and trademarks. Thomas Edison, whom the popular press proclaimed the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” proved himself a precocious wizard of branding as well. Edison identified himself personally with all the merchandise he marketed. He presented himself as a brand, and his characteristic signature, executed with a flourish and duly filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on May 27, 1899, became one of the most recognizable logos in American manufacturing history.9

“He presented himself as a brand, and his characteristic signature became one of the most recognizable logos in American manufacturing history.”

The “Thomas A. Edison” signature trademark prominently adorned Edison phonographs and recordings as well as other consumer products—and ads such as this one from 1901. The signature trademark became a logo familiar “all over the world.”

The Edison signature logo represented the identity Edison’s achievements had built for him. Consumers were eager to invest in his innovations because they felt that they were investing in no less than Thomas Alva Edison himself. The promotion of one invention after another became that much easier for Edison’s companies, thanks to the personal identification of each innovation with the inventor behind it. Attach his name to a product, and it was bound to sell. Edison so valued his signature trademark that when his own son, Thomas A. Edison Jr., sold the use of his name to promote a bogus electromechanical medical device—an item of expensive quackery—Thomas A. Sr. paid the young man a stipend for life in exchange for his promise never to use his own name in connection with any product.

BIRTH OF THE RETAIL EXPERIENCE

The post–Civil War explosion in manufacturing, especially of consumer goods, both drove and was driven by a revolution in American retailing. Philadelphia merchant John Wanamaker set the pattern for the modern department store when he moved his men’s clothing store to a remodeled Pennsylvania Railroad depot in 1876, a move that coincided with the great Centennial exhibition (see chapter 1). Before the nineteenth century closed, all the principal American cities had great department stores, which became even greater at the opening of the new century. From 1910 to 1911, Wanamaker redesigned and enlarged the iconic Philadelphia store, commissioning Daniel H. Burnham, the Chicago architect who drew up the master plan for improving that city’s post–Great Fire lakefront. Retailer Rowland Hussey Macy built four dry goods stores in Massachusetts between 1843 and 1855 before opening a larger store in New York City in 1858. Over the years, he expanded this establishment into adjacent buildings. In 1895, brothers Isidor and Nathan Straus bought the Macy company but retained its valuable name and, in 1902, moved into a five-story building on Herald Square, which was extensively expanded over the years and advertised as the “World’s Largest Store.”10

In 1876, Philadelphia men’s clothier John A. Wanamaker moved his store to a vacant Pennsylvania Railroad depot, which he remodeled to create the modern American department store. Photograph c. 1896.

In Chicago, Massachusetts-born Marshall Field worked for Cooley, Wadsworth & Co., the city’s biggest dry goods merchant, beginning in 1856. By 1862, Field was a partner in the firm and, by the 1880s, became a spectacular success in dry goods. Like Wanamaker in Philadelphia, however, Field recognized that retailing had fallen badly out of step with the middle class—the consumer class—rising in Gilded Age America. Before the Civil War, retail business was conducted overwhelmingly by individual proprietors of dry goods stores, “general stores,” butcher shops, grocer’s shops, and by an array of specialized tradespeople—shoemakers, tailors, craftspeople in various fields. The success or failure of these businesses depended on reputations, which were built on word of mouth within the community. As American cities grew and more of the population became not only urban but more transient, moving from city to city or from one neighborhood to another within the same city, retail businesses became larger but also lost much of the personal connection. There was both less motivation and less opportunity for building a local reputation, and, increasingly, the governing principle in retail transaction became “caveat emptor,” let the buyer beware. In other words, instead of merchants having an implied obligation to stand behind their products, the burden was on the consumer to practice due diligence and thereby avoid being deceived or disappointed. Like Wanamaker, Field saw that increasingly empowered post–Civil War consumers expected merchants to treat them very well indeed. Like Wanamaker, he was determined to appeal to and satisfy this expectation—partly by standing behind his merchandise with a no-questions-asked refund policy and also by providing a friendly, courteous, even luxurious shopping environment in which merchandise would be helpfully presented to customers, never forced on them. Importantly, Field recognized that women were the major shoppers in most families, and so he designed his Chicago store with women in mind and trained his employees to appeal to them. His business motto was “Give the lady what she wants.”11

From left: Wanamaker’s majestic interior court (photograph c. 1968) houses the largest operational pipe organ on the planet, making it a true cathedral of commerce; Chicago’s Marshall Field’s on State Street (c. 1908) reigned as the city’s most elegant department store until 2006, when the company was purchased by Macy’s; a photograph of Macy’s New York flagship department store (c. 1908), which claimed the title of “biggest store in the world.”

THE RISE OF FIVE-AND-DIME AMERICA

Access to a wide array of appealing goods as well as possession of the financial wherewithal to purchase them became both a symbol of middle-class status and a feature of economic life in the Gilded Age. Merchants like Wanamaker, Field, and others saw their mission as not just selling merchandise, but creating and offering a retail experience of luxury and self-indulgence. Yet that came at a cost. Department store goods were not cheap. Moreover, prices—which reflected the “overhead” of all the amenities the stores offered—were nonnegotiable. Whereas shoppers could haggle with the general store owner, they could not argue with a price tag. Although the productivity of the Gilded Age substantially fostered the American middle class, whose members had sufficient disposable income, it also enlarged the class of low-skilled and unskilled labor, families that barely scraped by and had to make every penny count. Common sense suggests that merchants had little incentive to address a market that could afford so little. The Woolworth brothers, Frank and Charles, thought differently, however. Where most retailers saw no business opportunity in the sub-middle class, the Woolworths recognized an underserved segment of the vast American consumer market.

“The Woolworths recognized an underserved segment of the vast American consumer market.”

While the department store was at the high end of the Gilded Age retail spectrum, the Woolworth “five-and-ten” was at the low end. Entrepreneur Frank W. Woolworth created chain-store retailing and offered an array of goods anyone in possession of a spare dime could afford. Photograph c. 1925.

Frank W. Woolworth opened the first five-cent store in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on June 21, 1879. (Business histories and textbooks often call this type of modest commercial emporium a “variety store,” but they are more commonly known as the “five-and-ten,” “five-and-dime,” “five-cent store,” or just plain “dime store.”) The very next month, he brought his brother into the business and, together, they opened another store in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The stores had been inspired by the success Frank had had when his employer, a Watertown, New York, dry goods merchant, allowed him to set up a five-cent table in his store. The table immediately became the busiest part of the store. The stores Frank and Charles opened expanded the five-cent table to the entire store (the price ceiling was eventually increased to ten cents).

Price was the great driver of the Woolworth business concept, but it was not the only ingredient in the brothers’ formula. First and foremost, they created an economy of scale with a chain-store concept. Both the village general store and the palatial department store were one-offs. The five-and-dime store, by contrast, would be standardized nationally. As with many of the products it sold, the chain itself would be a brand, with a reputation for low price and high value. In contrast to other merchants who specialized in cheap goods, Woolworth stores would be pleasant, new, clean, and brightly lit. The sawdust-covered rough wooden floors of the small-time general store were replaced by clean wood, polished to a high sheen. Small goods—and much that the stores sold was small—were featured either in gleaming glass cases or open gondola displays, which allowed customers to pick up, handle, and closely examine the goods. There was an emphasis on self-service. Unlike the old general store, where the goods were put on floor-to-ceiling shelves behind a continuous counter, so that customers had to ask a clerk or proprietor for service, Woolworth stores encouraged customers to pick out what they wanted for themselves and, as they were preparing to leave the store, to bring their purchases to the clerk behind a well-designed, shiny mahogany counter. If a customer needed assistance, an employee was there to help—but most customers were content to serve themselves. This reduced the number of employees required as well as the level of training and experience needed. The result? Lower overhead costs. Best of all, far from perceiving this as a corner-cutting reduction in service and convenience, customers truly enjoyed browsing and selecting without the intervention of an impatient or pushy salesperson.

The Woolworth business model proved highly successful, and other chains joined the originator of the five-and-dime, most notably Ben Franklin Stores, W. T. Grant, S. S. Kresge Company, and S. H. Kress & Co. All were successful for a long time, but none more than Woolworth, which operated 596 stores nationwide by 1912. Together, however, the dime-store companies built thousands of stores across the nation, and although there was nothing gilded about these modest and efficient establishments, most of them prospered through more than three-quarters of the twentieth century and linger today as perhaps the most affectionately remembered institutions of the Gilded Age.

THE TRIUMPH OF MAIL ORDER

The department stores provided a magnificent sales platform for many of the products post–Civil War manufacturers turned out, and the dime stores served consumers who were priced out of the department store offerings. Not that dime stores appealed exclusively to lower-income shoppers, however. Even consumers with the means to patronize department stores needed the everyday products purveyed by Woolworth and the like. True, many of these five-and-dime items could be purchased in a department store as well, but those emporiums were generally located “downtown” and required public transportation to get there. The dime stores were neighborhood establishments, with many within walking distance of the customers they served. In short, they offered not only value for money, but convenience as well.

Yet one group of consumers was still left out, namely the majority of Americans who lived in rural America, mostly on farms. In 1870, 25.7 percent of Americans lived in urban areas. By 1900, as the Gilded Age ended, 39.6 percent were urban residents.12 In 1872, Chicago merchant A. Montgomery Ward took a step toward addressing the roughly 75 percent of American consumers who lived far from either department stores or dime stores or, for that matter, traditional general stores. He reasoned that there was one way a merchant could easily reach these potential but hitherto underserved customers—via the U.S. mail. Accordingly, he created a 280-page catalog and mailed copies to thousands of farmers in the Midwest. With this, Montgomery Ward and Company became the nation’s first mail-order house.

Mail-order retailing—pioneered by Montgomery Ward—reached consumers wherever they lived, thanks to the U.S. Mail’s RFD (Rural Free Delivery) service.

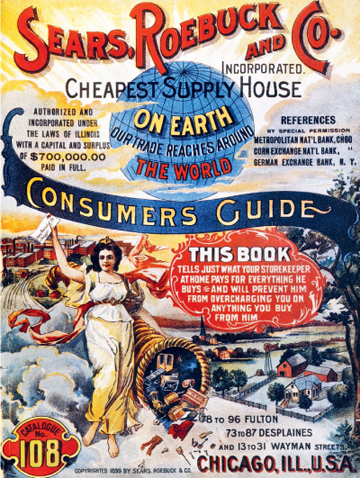

Montgomery Ward—affectionately known as Monkey Ward—became highly successful and inspired imitators. At least one of these took the mail-order concept well beyond Ward’s model. Richard W. Sears began his mail-order operation in 1889 as a way of selling watches to customers who had little or no access to merchants who handled this specialized item, but still needed good watches.13 To watches, Sears soon added jewelry and, from this base—in partnership with Alvah C. Roebuck—he built a general mail-order business. Like Ward, Sears advertised his products in catalogs sent to farm families. Sears was the Amazon of the turn of the century. Among the company’s merchandise were food, clothing, machinery, tools, stoves, and much more, even a complete kit for building your own Sears Craftsman Bungalow. The Sears Catalog became legendary for making available anything and everything a family, especially a farm family, might possibly need or want. And since most farmhouses lacked indoor plumbing, back copies of the catalog served both as reading matter for the outhouse and toilet paper, too. Sears printed it on soft, smooth paper stock. By 1893, mail-order sales exceeded $400,000, and by 1895 were at $750,000.14

Although Ward “invented” mail-order merchandising, Richard Warren Sears and his partner Alvah C. Roebuck created the most popular and plentiful mail-order catalog anywhere in the world. Not only did it promise variety, it promised value as the “Cheapest Supply House on Earth,” as noted on this 1899 catalog cover.

“The catalogs extended what might be called the consumer franchise to every corner of the country, no matter how remote.”

Wards and Sears were joined by the National Cloak & Suit Co. just before the turn of the century, and by Spiegel in 1905. Other, smaller mail-order houses also sprang up late in the nineteenth century. Together, the catalog companies changed the lives of American consumers and none more than farm families across the country. Isolated in rural areas and often with limited funds, these families could afford neither the time nor the expense of shopping for goods in towns and cities. The catalogs extended what might be called the consumer franchise to every corner of the country, no matter how remote. Retail mail order brought the Gilded Age to the farm. In the country, as in the city, the mass of Americans had entered the post–Civil War era as seekers of little more than the means of subsistence. Urban or rural, they all emerged from the Gilded Age as avid consumers, united not only by the flag and other traditional patriotic symbols of the republic, but by the colorful and varied brand iconography of corporate America.