CHAPTER 6

STATUE AND ISLAND

The first that Americans saw of what would be the most iconic symbol of the Gilded Age was part of a right forearm and all of a hand, which grasped a giant torch surmounted by a gracefully sculpted flame. Together, the partial forearm and hand piece was perhaps 25 feet (7.6 m) high, rising out of the ground from a small building that served as its base. The torch, from bottom to flame tip, was about 38 feet (11.6 m). The hand alone was 16½ feet (5 m) long, including its index finger, which was 8 feet (2.4 m) long.

As big as it was, this work was a mere fragment that was exhibited in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park as part of the great Centennial Exposition. The big show opened on May 10, 1876, but the sculpture did not arrive until August—too late to be included in the official catalog. For this reason, it did not bear the name that its creator, the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi had given it, Liberty Enlightening the World. Instead, it was known simply as “The Colossal Arm” or the “Bartholdi Electric Light.” (The titanic fragment was unlit, but was advertised as part of a planned “illuminated statue.”)1

What most Centennial visitors who saw the sculpture liked most about it was that they could climb up to the balcony at the base of the torch flame and get a lovely view of the fairgrounds. After the Centennial closed on November 10, the arm was transported to New York City, where it was displayed in Madison Square Park for a number of years before it was returned to France, its country of origin.

There was, in fact, nothing American about this massive fragment of sculpture, which Bartholdi intended to serve as a harbinger of what an American poet, Emma Lazarus, would later call “The New Colossus”—an allusion to the great statue of Helios, Greek titan of the sun, erected in 280 BCE on the island of Rhodes. An earthquake destroyed the statue in 226 BCE, but at a reported 108 feet (33 m) high, it was about 50 feet (15 m) shy of the Statue of Liberty as measured from the top of its base to the tip of its torch. Still, as the tallest statue of its age, the Colossus of Rhodes is considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, pictured here, intended his Statue of Liberty to be accepted as a gift from France to the United States, its comrade in revolutionary liberty, equality, and fraternity.

LADY LIBERTY

The idea for a new Colossus is said to have originated in a conversation between Bartholdi, already famed as a creator of monumental sculpture, and his friend Édouard René de Laboulaye, a poet, a jurist, and a passionate abolitionist. The two men are supposed to have discussed the matter over dinner at Laboulaye’s house in Versailles in 1865, a month or two after the end of American Civil War. Inspired by the Union’s victory, which brought with it an end to slavery in America—in effect belatedly perfecting and completing the great American Revolution against tyranny—the abolitionist told his sculptor friend, “If a monument should rise in the United States, as a memorial to their independence, I should think it only natural if it were built by united effort—a common work of both our nations.”2 Not everyone agrees that this is how the Statue of Liberty began. U.S. National Park Service researchers date its origin five years later, in 1870, but they still credit Laboulaye with having inspired the project as a commemoration of the end of slavery and, therefore, the realization of the full promise of American independence.3

But the path from inspiration (whether in 1865 or 1870) to execution was neither quick nor easy. Bartholdi and Laboulaye were liberal idealists. The government of France under Emperor Napoleon III was, by contrast, downright repressive. The two men were under no illusion that the monarchy would support in any official, let alone financial, way a French monument to celebrate the overthrow of a monarchy. If we believe the traditional chronology of Bartholdi’s inspiration—that it came in 1865, rather than the more recent revision of the time line—Bartholdi, perhaps discouraged by the prospects for Liberty Enlightening the World in the prevailing political climate, journeyed to Egypt toward the end of the 1860s to propose to that nation’s ruling khedive that he commission a massive lighthouse in the form of an ancient female fellah (peasant farmer). This figure, to be erected at Port Said, the Mediterranean entrance to the Suez Canal, would be robed and would hold aloft a giant torch—though (based on surviving drawings) the actual lighthouse beacon may have been intended to emanate from a band encircling the statue’s forehead. In some sketches, the figure’s face is veiled. One modern scholar, Edward Berenson, writes that Bartholdi “produced a series of drawings in which the proposed statue began as a gigantic female fellah … and gradually evolved into a colossal goddess4 In any event, Bartholdi presented to the khedive something vaguely resembling the Statue of Liberty, an echo of an ancient monument to serve the practical purpose of guiding modern ships to the entrance to the one of the great wonders of the modern world, the Suez Canal, which was nearing completion when the sculptor called on the khedive. Bartholdi proposed to call the work Egypt Brings Light to Asia.5

The Egyptian ruler turned the project down, but the idea and perhaps even the drawings may have found their way into the design for the Statue of Liberty. Long-accepted tradition holds that the model for the American statue was the artist’s mother, Augusta Charlotte Bartholdi, but if the work celebrating American independence was actually recycled from a proposed lighthouse on the Suez Canal, it is possible that the icon of American liberty was created by a French sculptor from an Egyptian model, who was quite likely a Muslim and may even have been a Muslim black woman. At least one of the models for the Egyptian project was described as a “statue of a Nubian woman,” and, in 2000, Dr. Leonard Jeffries Jr., a professor of African American studies at City College, in New York, “said his research showed that early models of the statue ‘were more Negroid,’ adding that ‘the idea of the black Statue of Liberty has been kept out’ of historical accounts.”6

Rejected by Egypt’s khedive, Bartholdi decided to return to the American project, but was almost immediately stymied by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. This not only created a logistical obstacle, it demanded Bartholdi’s service when his militia unit—in which he served as a major—was called up. The war was of especially intense concern to Bartholdi because he was a native of Alsace, the province bordering Prussia. Fighting began at the end of July 1870 and, by September 1, 1870, Napoleon III—who had assumed personal command of French forces—lost the Battle of Sedan and surrendered himself as a prisoner of war. The so-called Government of National Defense, which overthrew the Second Empire, continued to fight, but, for all practical purposes, the Franco-Prussian War was over, Alsace was soon ceded to Prussia (which became the center of the new German Empire), and the monarchy was replaced by the Third French Republic. The loss to Germany of his home province must have been a hard blow for Bartholdi, but the establishment of the republic was a blessing for him. It created the liberal political and cultural climate in which a statue dedicated to liberty could find support. Bartholdi sailed for the United States in June 1871, bearing letters of introduction from Laboulaye, whose reputation as a pro-Union abolitionist made him popular in Washington political circles.

When he embarked, Bartholdi was simply interested in promoting a monumental statue to the cause of American independence, a cause in which France had played so central a role during the American Revolution. As his ship glided into New York Harbor, however, Bartholdi’s attention became riveted on Bedloe’s Island, which instantly struck him, for reasons both topographical and symbolic, as the ideal site for his statue. Any ship entering the harbor had to sail past the island. It was impossible to miss it. A statue raised upon it would welcome all who entered America through this port. After he himself had landed, Bartholdi made inquiries about Bedloe’s Island (renamed Liberty Island by an act of Congress in 1956). The news was auspicious. It was owned by the federal government, having been ceded to the United States in 1800 as a site for harbor fortifications. The land belonged to no individual, no city, no state. It belonged to the people of the United States of America. As Bartholdi saw it, this was perfect.

Thanks to his letters of introduction, Bartholdi got the ears of movers and shakers in New York, and he even had a sit-down with President Ulysses S. Grant, who saw no problem in obtaining Bedloe’s Island for the statue. Thus encouraged, Bartholdi stumped the country, traveling coast to coast by train in two round-trips, buttonholing influencers and opinion makers everywhere. Concerned that this top-down approach would not be sufficient to win popular support, he decided to return to France and, with Laboulaye’s aid, plotted out a comprehensive public relations campaign. The two men also discussed elements of the design, and the sculptor enlisted the participation of the distinguished Beaux Arts architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc to address the structural engineering aspects of the statue, including the construction of the base, the pier to which the skin of the sculpture would be attached, and the material—sheet copper—that would be used. As Bartholdi solved the essential problems of fabrication, the French economy began to reap the benefits of republican government. Although the nation was obligated to pay costly war reparations to the German Empire, there was a new spirit in France, a new productivity, and a strengthening economy. Indeed, it was one of those rare instances in which losing a war actually improved the welfare of the nation.

In 1875, Bartholdi observed the growing interest in the upcoming Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and realized that this would be a natural platform from which to gain the support of the American public for his statue. He and Laboulaye founded the Franco-American Union as a fund-raising organization, and Bartholdi went ahead with the fabrication of the arm and torch and part of the head. While the arm and torch were exhibited at the Centennial and afterward resided for a few years in New York’s Madison Square Park, the head, completed in 1877, was displayed at the 1878 World’s Fair in Paris.

Bartholdi sculpted the arm and the head of the Statue of Liberty on spec, while he was still raising funds for the statue. The head was exhibited in New York’s Madison Square Park before it was returned to Paris, where it resided in a city park until it was dismantled and shipped to the United States, along with the rest of the statue. Taken in Paris, this photograph dates from 1883.

Directed by the Franco-American Union, various fund-raising organizations were put into operation, the most important of which, in the United States, was the American Committee, which included among its members a young Theodore Roosevelt. On his last full day in office, March 3, 1877, President Grant signed a joint resolution of Congress, authorizing the chief executive to accept the statue from France (whenever it was finished) and to select a site for it. Grant’s successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, took his recommendation of Bedloe’s Island as the site of choice.

ON SEPTEMBER 17, 1879, SIXTY-FIVE-YEAR-OLD VIOLLET-LE-DUC, succumbing to illness, died in his villa in Lausanne, Switzerland. This was a blow to the ongoing construction of the statue. Although he had directed the construction of the arm and the head, Viollet-le-Duc died before preparing plans for the main engineering. This seemed like a major setback; however, in 1880, Bartholdi hired no less a figure than Gustave Eiffel, renowned designer of extraordinary ironworks, the most famous of which, the Eiffel Tower (completed in 1889), was nearly a decade in the future. Eiffel quickly abandoned Viollet-le-Duc’s idea of a rigid masonry pier and instead, in collaboration with Maurice Koechlin, a structural engineer, designed a truss tower built entirely of wrought iron. Mindful of the tremendous stress to which the copper skin would be subjected, Eiffel and Koechlin devised a system of internal bearings and couplings that allowed the truss tower to move as the copper skin contracted and expanded with changes in temperature. The support system also moved with the winds that were often strong over the harbor. The Gilded Age would see the birth of the modern skyscraper (see chapter 8), which depends on steel-cage and curtain-wall construction, in which the outer structure of the building is effectively attached to and suspended from an inner structure. This outer “curtain wall” bears no structural load, which is carried entirely by the steel cage. The armature of the Statue of Liberty was the very first example of the engineering that produced the skyscraper. Thus, while the statue was a symbol of political revolution, its construction itself exemplified a revolution in engineering and architecture.

The Statue of Liberty under construction in Paris, about 1883. Bartholdi stands second from right.

FUND-RAISING, PRIMARILY TO BUILD THE PEDESTAL FOR THE STATUE, proved to be a challenging endeavor. Both the New York State government, under Governor Grover Cleveland, and the U.S. Congress refused to appropriate funds. Among those scrambling to raise private funds was a group of artists and writers who auctioned off paintings and literary manuscripts. Among the manuscripts on offer was a sonnet written in 1883 by Emma Lazarus, titled “The New Colossus”:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Despite the efforts of Lazarus and many others, it appeared that a lack of funding would halt construction of the pedestal on Bedloe’s Island and might even prevent the United States from accepting the statue from France. This predicament spurred the cities of Boston and Philadelphia to make rival bids for the monument, each offering to take delivery of the statue for its relocation in their town. Publishing mogul Joseph Pulitzer did not want New York to lose the statue and so responded to the funding crisis by mounting a drive to raise $100,000 by promising to publish in his New York World the name of every person who contributed—regardless of the size of the contribution. The result was a torrent of donations, many in pennies, nickels, and dimes from American children. Fully funded, pedestal construction finally proceeded apace. In order to test the fit of all components, the statue had already been put together in Paris. Bartholdi now ordered that it be dismantled (each component carefully numbered; there were approximately 350 pieces) and loaded aboard the French cargo steamer Isère. When that vessel arrived in New York with its cargo on June 17, 1885, American enthusiasm for the statue had become a phenomenon, and an estimated 200,000 people jammed the docks to greet the arrival. The dismantled statue had made the transatlantic crossing in about two hundred crates, which were offloaded but remained unopened until April 1886, when the pedestal was finally completed. The pedestal, a truncated pyramid in shape, was too wide to permit the construction of scaffolding. Workers were therefore obliged to place and attach the statue’s copper skin, section by section, while dangling from ropes. As precarious as this was, there were no fatalities—something that all concerned took as a blessed omen.

The statue is obscured by smoke from the massed artillery fired to salute the arrival of President Grover Cleveland, who came to dedicate the monument.

A week before dedication day, slated for October 28, 1886, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers intervened with an objection to Bartholdi’s proposal to illuminate the torch with powerful floodlights. The Corps feared that this would blind harbor pilots negotiating the busy waters of New York and New Jersey. As designed and built, the torch was sheathed in opaque gold leaf to reflect the sun during the day and floodlights at night. With astonishing improvisational agility, Bartholdi accommodated the Corps of Engineers by ditching the floodlights. He then cut small windows or portholes in the torch, put electric lights inside the structure—Edison had patented the incandescent electric lamp just seven years earlier—and powered them from a generating plant built on the island.

President Grover Cleveland (yes, the very politician who had earlier, as New York governor, vetoed a $50,000 appropriation to aid construction of the pedestal) presided over the dedication of the Statue of Liberty on October 28, 1886. Although a grand parade in Manhattan drew as many as a million onlookers, according to some sources, only a select audience of dignitaries were invited to Bedloe’s Island to witness the dedication itself. Adding further insult to this injury was the absence of any women—save the granddaughter of Suez Canal developer Ferdinand de Lesseps and Jeanne-Emilie Baheux de Puysieux, Bartholdi’s wife—at this ceremony dedicating a female representation of liberty. The official excuse for the omission was a fear that ladies might get hurt in the crowd.

None of the speakers at the event—not de Lesseps, New York senator William M. Evarts, President Cleveland, or the keynote speaker, politician and attorney Chauncey Depew—said anything that history remembers. Certainly, none mentioned the immigrants—the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free”—whom Emma Lazarus’s sonnet explicitly identified with the statue. Indeed, her words are perhaps the only ones that have resonated down through the years. But the poem was not part of the dedication ceremony. Doubtless, those in charge of the event had no idea of the existence of the poem, which had been forgotten even before Emma Lazarus died, apparently of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, in 1887 at the age of thirty-eight. Her friend, Georgina Schuyler, seeking some memorial for her, succeeded in getting a bronze plaque engraved with the sonnet affixed to an inner wall of the pedestal, but this did not happen until 1903. In 1986, the plaque was moved to a permanent Statue of Liberty exhibit inside the pedestal, and that is where visitors to Liberty Island can find it today.

YEARNING TO BREATHE FREE

There are three prominent but small islands in New York Harbor. Liberty Island, on the New Jersey side of the harbor, and the larger Governor’s Island, on the New York side, are the first to greet travelers sailing into the port of New York. Just to the north of Liberty Island, on the New Jersey side of the harbor and, as it were, behind the Statue of Liberty, is Ellis Island, about a mile (1.6 km) off the tip of lower Manhattan.

It was originally a destination—first for the Algonquians and then for the Dutch and English—because of its rich oyster beds. Around 1679, the island was given to—and named after—William Dyre, who would become the thirteenth mayor of New York. In 1774, a merchant named Samuel Ellis bought Dyre Island and renamed it after himself. After Ellis died in 1794, ownership of the island was disputed until New York State bought it in 1808 and immediately sold it to the federal government for the purpose of building an arsenal and fort.

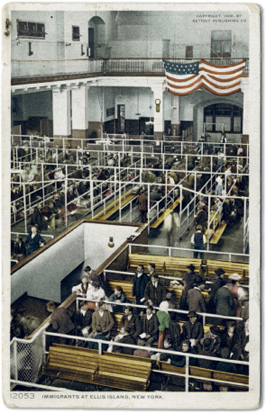

Ellis Island processed as many as fourteen million immigrants between 1892 and 1895 and 1954. The Main Building, an ornate Renaissance Revival structure, was designed by architects William Alciphron Boring and Edward Lippincott Tilton. It was completed in 1900.

After the creation of the U.S. Bureau of Immigration in 1891, Ellis Island was deemed the best location for new immigration processing facilities. Since 1855, Castle Garden—a circular fort built of sandstone at the very tip of Manhattan in what is today Battery Park—had served as the “Emigrant Landing Depot,” which was operated not by the federal government, but by the state of New York. Functioning as the processing station for incoming immigrants, it was woefully inadequate to cope with the Gilded Age influx. It had been built originally as a fort called West Battery in 1808–11; was renamed Castle Clinton in 1815; and was then repurposed, when the army left it in 1821, as a place of “public entertainment.” In 1824, now called Castle Garden, it served as a combination beer hall, theater, and opera house until the state took it over in 1855.

The newly created Bureau of Immigration opened its first facilities on Ellis Island on January 1, 1892. The main building was three stories high and was complemented by a suite of outbuildings. The entire complex was built of Georgia pine. Predictably, the whole wooden thing burned down in 1897—miraculously, without loss of life—and a fireproof complex, built of brick in an almost playful Renaissance Revival style, was completed in 1900. For the next sixty-two years, Ellis Island served not only as the main point of entry for America’s immigrants but also as a symbol of the hopes, aspirations, fears, and disappointments of all those who entered the country from foreign lands.

The main purpose of the island facility was as a cordon sanitaire, where masses of immigrants could be received, examined for disease, and, as deemed necessary, quarantined, admitted directly to the mainland, or deported. For millions, Ellis Island was either the portal to the New World or the locked gate from which they were sent back to the Old.

During the height of its activity at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, Ellis Island processed, in its flag-draped Great Hall, hundreds of thousands of people a year; at least 12 million—perhaps as many as 14 million or more—passing through the place between 1895 and 1954, when the facility was closed.8

While Ellis Island served a necessary practical purpose, it was also a symbol of the nation’s attempt to assert control over an endless influx of immigrants. It was a reflection of the balancing act that was always part of the American experience, but never more so than during the Gilded Age. Government administrators struggled to weigh the nation’s fears of an assault on its “American identity” against the demands of industry, which sought cheap immigrant labor in ever-increasing numbers from the end of the Civil War through the early 1900s. Immigration was hardly new to America, of course; however, from 1866 to 1900, more immigrants arrived than in the preceding 250 years. Moreover, they were of different origin than those who arrived before the Civil War. Overwhelmingly, the first waves of U.S. immigrants were Western Europeans, mostly from the British Isles, Ireland, Scandinavia, and Germany. After the Civil War and throughout the Gilded Age, the predominant influx was still European, but most came from Southern and Eastern Europe—Italians, Eastern European Jews fleeing persecution, and other Slavic peoples. The era also saw a sharp rise in the immigration of Chinese and Japanese, especially on the West Coast.

This color postcard from 1908 shows the Great Hall, through which arriving immigrants were processed and given medical examinations. Depending on the state of an immigrant’s health, he or she would be admitted to the country, held for quarantine, or rejected and put on the next available outbound ship.

None of these groups came uninvited. Industry demanded cheap immigrant labor, and the government homesteading initiatives begun during the Civil War and continuing into the 1890s were intended to populate the West, expanding the nation’s agriculture while also creating new markets for the products of U.S. manufacturers. As for the immigrants, many did achieve what they sought by leaving their home countries—greater liberty, escape from persecution, and an opportunity to achieve a degree of material security and prosperity. Yet there was also a backlash against immigrants and immigration. While “native-born” Americans generally tolerated and even welcomed the early waves of immigrants, whose Western European cultural, religious, and linguistic profile was generally similar to their own, the immigrants of the Gilded Age came with differences that some found unnerving and even intolerable. Eastern European culture, language, and religion—especially in the case of the Jews and the Roman Catholics—struck many as too different, too “other,” to ever be successfully assimilated into the American Protestant mainstream. Newspapers, the halls of Congress, and even some churches and university classrooms were filled with talk of an “immigrant problem” and an “immigrant threat.” Both nationally and locally, anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic organizations sprang up, most notably the American Protective League and the Immigration Restriction League. Such organizations rallied support to pressure members of Congress to enact legislation restricting immigration, at least from certain places deemed undesirable.

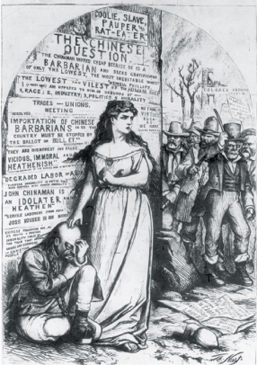

Generally, the more “alien” an immigrant group was perceived to be, the stronger the objections to it. Chinese immigration, which had been encouraged and welcomed during the western Gold Rush era of 1848 to the mid-1850s and the great western expansion of the railroads during the 1860s and early 1870s, elicited ugly anti-Chinese agitation and even violence during the middle and late 1870s. Growing anti-Chinese sentiment, especially among the working class, which feared competition for laboring jobs, resulted in the 1882 passage of “An Act to Execute Certain Treaty Stipulations Relating to Chinese”—universally known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. The first U.S. law specifically aimed against a racial or ethnic group, the act barred Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years. In 1892, the Geary Act renewed the ban for another ten years, and, in 1902, the ban was made permanent until its repeal, during World War II, by the Magnuson Act of December 17, 1943.

This undated photograph shows Eastern European immigrant arrivals on Ellis Island. These immigrants were looked on less favorably than those from Western Europe, but both were far more readily welcomed than immigrants from Asia or Africa.

Unquestionably, of course, the Chinese Exclusion Act was anti-Chinese, but, even more to the point, it was anti-American. This tragic irony was made all the more poignant by its passage just four years before the Statue of Liberty was dedicated. When Joseph Pulitzer, himself a Jewish immigrant from Hungary, conducted in the pages of his New York World a campaign to fund the construction of the pedestal for the statue, one reader, Saum Song Bo, a Chinese immigrant living in New York City, wrote a letter of protest to the editor:

[T]he word liberty makes me think of the fact that this country is the land of liberty for men of all nations except the Chinese. I consider it an insult to us Chinese to call on us to contribute toward building in this land a pedestal for a statue of Liberty. That statue represents Liberty holding a torch which lights the passage of those of all nations who come into this country. But are the Chinese allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from the insults, abuse, assaults, wrongs and injuries from which men of other nationalities are free?

If there be a Chinaman who … desires to make his home in this land, and who, seeing that his countrymen demand one of their own number to be their legal adviser, representative, advocate and protector, desires to study law, can he be a lawyer? By the law of this nation, he, being a Chinaman, cannot become a citizen, and consequently cannot be a lawyer….

Whether this [1882] statute against the Chinese or the statue to Liberty will be the more lasting monument to tell future ages of the liberty and greatness of this country, will be known only to future generations.

Liberty, we Chinese do love and adore thee; but let not those who deny thee to us make of thee a graven image, and invite us to bow down to it.9

Industries in need of cheap manual labor successfully lobbied Congress to allow large numbers of Chinese laborers to immigrate to the United States. In China, so-called labor agents lured prospective immigrants to America with promises of good, clean work in a land of equality and law. The new arrivals were invariably disappointed and, often, horrified.

Saum Song Bo was not the only immigrant who felt betrayed by what late nineteenth-century America offered. Among European immigrants, many had been lured to the United States by recruiters, called labor agents, who promised high wages and steady employment in the Promised Land across the Atlantic. The Western railroads, which owned vast tracts of land along their rights of way, launched propaganda campaigns throughout Europe that advertised the easy availability of cheap land in the Golden West. The colorful pages of the railroad flyers led many immigrants to believe they would soon own farms in a Garden of Eden. In fact, most newcomers had to content themselves with factory jobs in the densely populated urban ghettos of the East Coast. Many immigrants found themselves relegated to the ranks of the working poor. As journalists and reformers of the era documented (see chapter 14), they lived in dark, squalid, airless tenements. Yet the “Chinatowns,” “Little Italys,” and “Greek Towns” that appeared in a number of larger U.S. cities also became centers of ethnic and national pride and prosperity. Even as most first-generation immigrants eked out their living with low-paying jobs as unskilled factory laborers, they managed to lay the foundation for their children’s brighter future.

Not all immigrants chose to stay. About half of young, single, male Italians, Greeks, and Slavs who immigrated between roughly 1870 and 1900 remained in the States just long enough to earn the kind of money they could not hope for at home. Once they reached whatever monetary goal they had set, they returned to Europe. During the period of the Gilded Age, two of three Chinese immigrants went back to China, and while Mexico contributed many permanent immigrants, a large class of Mexican migrant laborers regularly moved back and forth across the border in rhythm with whatever employment opportunities presented themselves north or south of the Rio Grande.10

THE AGE OF IMMIGRANTS

By the numbers, the Gilded Age was the heyday of immigration in America. Behind the numbers, however, it was a period during which both the worst and the best of the immigrant experience emerged front and center in American civilization. The ugliness of anti-immigrant prejudice and, sometimes, even outright exclusion (as in the 1882 anti-Chinese law) hurt many and broke some. Most immigrants, however, never lost their faith in the promise of America. For them, the immigrant experience was a crucible that tested them and, in testing, made them stronger. Their endurance paid off for their children, who grew up American.

Daniel Griswold, director of the Center for Trade Policy Studies at the Cato Institute, a conservative American think tank, wrote in 2002 that, far from “undermining the American experiment,” immigration has “kept our country demographically young, enriched our culture and added to our productive capacity as a nation, enhancing our influence in the world.” Moreover, while many immigrants do “fill jobs that Americans cannot or will not fill” at the low end of the skill spectrum, they are also today “disproportionately represented in such high-skilled fields as medicine, physics and computer science.”11 The same was true during the Gilded Age. Immigrants took on many of the very dirty jobs “native-born” Americans spurned, but they also included in their ranks some of the nation’s greatest achievers. The likes of newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell, mathematician and electrical engineer Charles Steinmetz, physicist and futurist Nikola Tesla, naturalist John Muir, journalist Jacob Riis, Lincoln private secretary John George Nicolay, labor activist Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, Jewish immigrant author Abraham Cahan, and financier and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie are just a few of the immigrants who made their mark during the Gilded Age.

The Gilded Age pulled America in opposite directions.

As symbolized in the great Centennial Exposition of 1876—the first world’s fair—post–Civil War Americans had an urge to reach out into the world and to project themselves onto the global stage. They also proudly drew the world to themselves, inviting visitors and immigrants alike. Politically, the drive to project American power and influence expressed itself in the birth of American imperialism and a desire for the nation to be acknowledged as a world power. Economically, the industrial development and the Western settlement of the United States required an influx of immigrants from all over the world—to do industrial labor in the cities and to settle and cultivate the vast expanses of the nation’s West.

Even as the 1876 exposition in Philadelphia celebrated the technological present and future, it also looked back longingly on the previous one hundred years. In much the same way, the American nation opened itself to the world yet also sometimes recoiled in fear from it, retreating into an “America First” nativism that was both timid and brutal. The clash between the cosmopolitan and the parochial defined both the energy and the angst of the Gilded Age. Along with such material monuments as the Statue of Liberty and the buildings on Ellis Island, these dual motives of collective advance and withdrawal have survived beyond the end of the nineteenth century. Thus the history of American civilization in the twentieth century and into the first two decades of the twenty-first is marked by a national ambivalence that should be familiar to us by now, an urge to both strike out into the wider world and to retreat from it, to open up to others and to build walls against them, to embrace unfamiliar people and cultures and to push them away. As is true today, democracy in the Gilded Age was far from simple and never stood still for long.

Oftentimes, Chinese immigrants were subjected to prejudice and persecution. This 1871 Harper’s Weekly cartoon shows Columbia—the personification of America—preparing to protect a downcast Asian immigrant from an intolerant American mob.