CHAPTER 12

THE FRONTIER CLOSES

With good reason, we think of the Gilded Age as playing out largely in America’s big, mostly Eastern cities. The economic power of those cities, however, the driver of their productivity and growth, is to be found in the markets created by America’s westward expansion and by the raw materials of the West—from cattle and crops to oil and ore—that fed, fueled, and built the major cities. In this sense, Gilded Age enterprise and politics were ultimately the offspring of a national ethos that had been articulated as early as the run-up to the US-Mexican War (1846–48). In its 1844 presidential platform, the Democratic Party wrote of effecting the “re-occupation of Oregon and the re-annexation of Texas,” even though the United States had never previously occupied these places.1 By the word re-occupation, however, the party asserted a nonexistent right, advancing an imperialist agenda without risking a charge of imperialism. The idea was to court the support of expansionists without alienating more reticent or scrupulous voters. A year later, in July 1845, New York Post editor John L. O’Sullivan echoed the Democrats’ platform in an article titled “Annexation,” published in the United States Magazine and Democratic Review. “It is our manifest destiny,” O’Sullivan declared, “to overspread and possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.”2 He thus expressed a sentiment held by many Americans since the days of the Pilgrims and the Puritans: that America was a chosen land and that it was the providential destiny of white, Christian Americans to possess the entire American continent. The implication was that any war fought to realize this “manifest destiny” would be a just war—indeed, a holy war. Moreover, there existed a deeply held American belief that the acquisition of land was part and parcel of the “unalienable right” to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness mentioned in the Declaration of Independence.

From the beginning, the leaders of the American republic had been determined to avoid the fate of Europe, with its small elites addicted to luxury and its huge, discontented, and therefore inherently rebellious landless majorities. Even the privileged class in America argued that the nation’s great “experiment” in government depended on the prosperity of individual property holders. Widely distributed land ownership was a safeguard against dangerous concentrations of power. As citizens of a young country, its history but brief when compared with the histories of Old World nations, Americans developed what historian Drew McCoy called “a vision of expansion across space—the American continent—as a necessary alternative to the development through time that was generally thought to bring with it both political corruption and social decay.”3 This vision blended manifest destiny with manifest innocence—together, the very essence of what many have called “American exceptionalism.” It was the vision that moved journalist John Babson Lane Soule in 1851 to editorialize in the Terre Haute Express, “Go west young man, and grow up with the country.”4

Somewhere in the mix of divine mission and sheer romanticism, westward expansion was also driven by a growing feeling that the nation simply needed somewhere to put the influx of foreign immigrants, as packing them into cities was resulting in the creation of slums and the social misery that goes along with them. In any event, some combination of spiritual vision, a romantic yearning for the open spaces of the frontier, and the perception of demographic necessity motivated the United States to go to war with Mexico, and to acquire thereby most of what is now the American Southwest. The war effectively ended with General Santa Anna’s defeat at the Battle of Huamantla (October 9, 1847), and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (February 3, 1848) formally concluded hostilities.

This 1873 chromolithograph was made by George A. Crofutt after an 1872 painting by John Gast titled American Progress (and also Westward Ho!). It features an allegorical figure representing the spirit of “manifest destiny”—the idea that the American nation was providentially destined to spread from Atlantic to Pacific.

That was convenient timing, because on Monday, January 24, 1848, James Marshall, an employee of Northern California rancher John Sutter (1803–80), found gold in Sutter’s millrace, a discovery that triggered the great California Gold Rush later that year.

GOLD RUSH

Sutter had been born Johann August Sutter in Germany. Bankrupted there, he immigrated to America in flight from his creditors. He did not stop when he reached an East Coast port, but traveled overland, westward, in search of fortune. After going bust twice, he scraped together enough money to buy a ranch in California’s fertile Central Valley. Sadly, Marshall’s discovery of gold did Sutter no good at all. Not only did all his employees run off to look for more of what Marshall had found, but his ranch was soon overrun by gold seekers, who destroyed nearly everything in sight. So, once again, the luckless immigrant lost money, and he spent his last days fruitlessly petitioning Congress for restitution over losses he suffered in the Gold Rush.

Among those who unleashed the hordes on Sutter was a Mormon elder and newspaperman named Samuel Brannan. At the time of Marshall’s discovery, Brannan was staying the night at Sutter’s ranch while traveling. He collected a quinine bottle full of gold dust, returned with it to San Francisco—at the time a modest village called Yerba Buena—and ran through the dusty streets waving the bottle and bellowing, “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!”

Almost overnight, Yerba Buena’s population fell from a few thousand to a few dozen, as men threw down their tools or shuttered their shops and lit out for the Central Valley. Come midsummer, Brannan joined them—not to look for gold himself, but to make his fortune by selling picks, shovels, pans, and provisions from a brand-new ramshackle store he built right next to Sutter’s Mill. Before 1848 ended, about a quarter-million dollars in ore was taken from California streams and topsoil. It arrived in San Francisco in bottles and buckskin bags, old tins and beat-up shoes, and much of it was shipped East around the tip of South America in vessels that stopped along the way at ports of call in Hawaii, Mexico, Peru, and Chile. Experienced South American miners set sail up the coast, and by 1849, the mining population has swelled to ten thousand or so. Tales of golden nuggets just waiting to be gathered by the handful and riverbeds paved with gold spread throughout the rest of the United States. “Forty-niners,” as hopeful prospectors came to be called, gushed out of Atlantic seaboard cities, Midwestern villages, and Southern plantations—eighty thousand to a hundred thousand of them in 1849 alone. Yerba Buena exploded from a semideserted village to San Francisco, suddenly a major seaport. Prices for everything soared, as newcomers filled some five hundred bars and a thousand gambling dens. Life was counted cheap, but eggs went for $6 a dozen in town, and three bucks each in the gold fields.

In 1851, when this photograph of Portsmouth Square was made, San Francisco was a rough-and-ready Gold Rush boomtown of ramshackle buildings.

Few prospectors struck it rich, and most eventually limped back East, discouraged and broke. By 1852, when gold production soared to an annual high of $81 million, most of the “placer” (surface) gold was gone and large-scale, well-funded, mechanized mining companies had pushed out most of the individual prospectors. But many of those who established businesses to serve the forty-niners quickly grew wealthy, purveying merchandise and real estate at vastly inflated prices. Collis Huntington and Mark Hopkins made their money cornering the market in shovels and blasting powder, taking most of what prospectors hadn’t spent on gambling, drink, and loose women. Teamed with prospector-turned-shopkeeper Charles Crocker and mining-camp storekeeper Leland Stanford, they would become California’s Big Four, financial backers of the Central Pacific, the western portion of America’s first transcontinental railroad.

While the Big Four were the biggest success stories to come out of the Gold Rush—the precursors of the robber barons, others also laid the foundations of Western fortunes that rose higher and higher during the Gilded Age. John Studebaker earned enough cash making wheelbarrows for miners to expand his family’s small-time, Indiana-based wagon works into the nation’s biggest and best-known carriage maker. A Bavarian immigrant, named Levi Strauss, patented the use of copper rivets to reinforce the seams of the indestructible trousers he made for forty-niners out of canvas tent fabric dyed blue. Philip D. Armour was a laborer who saved enough to open a butcher shop in the gold fields, slaughtering and selling meat at exorbitant prices—and earning more than enough to take back with him to Milwaukee, where he built the nation’s biggest and best meatpacking plant. And then there were Henry Wells and William G. Fargo, two Easterners who had no intention of settling in the West, but who knew there was money to be made by running mule trains to keep miners supplied. They ended up creating the country’s premier stagecoach freight and passenger business before expanding into banking.

SODBUSTERS, COWBOYS, AND RAIL GANGS

The Gold Rush did not last long—scarcely a decade—but it nevertheless helped to make the West a destination for millions. In quest of overnight fortunes, the forty-niners were the advance guard of subsequent legions of farmers and tradespeople, looking not to get in, get a fortune, and get out, but to settle and build lives on the West Coast. On May 20, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln gave them a major incentive to do just that when he signed the Homestead Act of 1862. The law authorized any citizen (or immigrant who intended to become a citizen) to select any surveyed but unclaimed parcel of public land, up to 160 acres (64 ha), settle it, improve it, and, by living on it for five years, gain title to it.

With the nation torn apart by the Civil War, Lincoln hoped that the accelerated settlement of the West would strengthen what was left of the Union by creating an unbroken link between East and West. The Homestead Act, and several acts that followed, were also formulated to encourage orderly settlement by families, instead of the abusive exploitation by land speculators, large ranchers, and others. As an alternative to living on the land for five years, a homesteader could “preempt” the land after just six months’ residence by purchasing land for $1.25 per acre (0.4 ha). The homesteader could also exercise preemption to augment his basic 160-acre (64-ha) claim, though few settlers could ante up the $50 for the minimum purchase of 40 acres (16 ha) the government required. Another option for adding to the original grant was to make a “timber claim” by planting 10 acres (4 ha) of timber-producing trees. This entitled the homesteader to an additional 160 acres (64 ha)—an important incentive on the mostly treeless Western prairies, where the hard-packed soil was not naturally conducive to timber growth. Indeed, were it not for John Deere’s recently developed steel plow, the unyielding prairie soil would have been largely worthless for farming, and the Homestead Act might have had few takers. As it was, the homesteaders soon earned a nickname born of the soil. They were called “sodbusters,” and they farmed the prairie.

The sodbusters were not the only agricultural workers who plied the Western Plains. The Civil War converted many Texas ranchers into Confederate soldiers, and when they went off to fight, a lot them left their livestock to fend for themselves. By the end of the war, millions of head of cattle ranged free across the state. Hearing of this, a fair number of Southern young men, their region ravaged by combat and paid employment hard to find, went west to round up Texas strays, brand them, and drive them to market up North. That was how the trail cattle drive industry began, and if any one man can be said to have started the enterprise, it was former Texas Ranger Charlie Goodnight (1836–1929).

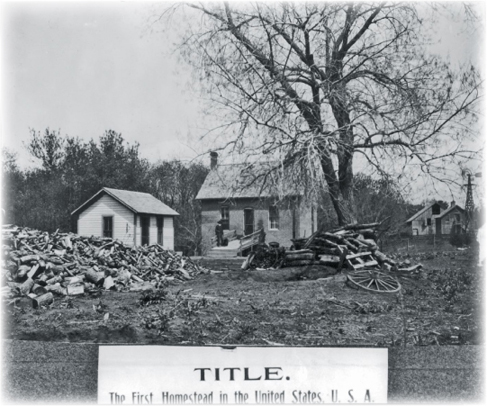

This rare photograph documents the first homestead claim made under the Homestead Act of 1862. The claimant was Daniel Freeman; the location was Gage County, Nebraska. The photograph was made in 1904, some four decades after the claim was staked.

He was born on a southern Illinois farm and came to the Brazos River country of Texas with his family in late 1845. There, in a land of longhorns running wild, he learned how to be a cowboy, to gather the animals and drive them to market for local ranchers. With his stepbrother as his partner, he gradually amassed a small herd of his own, but, like many other Texans, left ranching to fight for the Confederacy. Mustered out of the Texas Rangers a year before the Civil War ended, Goodnight and his stepbrother found that their original herd, numbering 180 head at the outbreak of the war, had grown to 5,000—a figure they supplemented by appropriating cattle on the open range. At this time, most ranchers were starting to drive their cattle to Kansas railheads for shipment to Eastern markets. With Oliver Loving, an old-time cattleman, Goodnight decided to move in the other direction, pioneering a trail to Colorado, where mining operations and Indian-fighting military outposts were creating a tremendous demand for beef. In 1866, Goodnight and Loving gathered 2,000 head of longhorns and, with eighteen riders, followed the Southern Overland Mail route to the head of the Concho River, where they liberally watered their stock for the long, dry trip across the desert. They lost some 400 head on the trail—300 of thirst, 100 trampled to death in the stampede that ensued whenever they reached a watering hole—but the first drive along the Goodnight-Loving Trail netted the partners $12,000 in gold.5

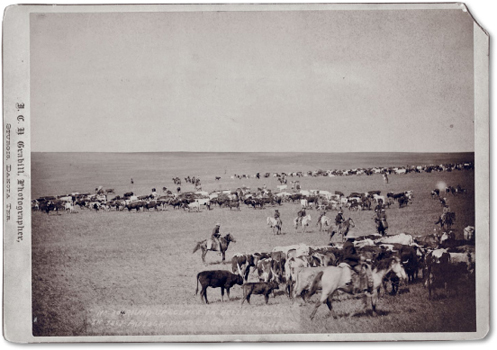

Painters and photographers never tired of portraying cowboys and cattle drives. Titled “Round-up Scenes on Belle Fouche [sic] in 1887,” this print was made by South Dakota photographer John C. H. Grabill. (Today Belle Fourche is the seat of Butte County, South Dakota.)

The Goodnight-Loving Trail was one of four principal Western cattle trails, which also included the Chisholm (from Brownsville, Texas, to the Kansas railheads of Dodge City, Ellsworth, Abilene, and Junction City), the Shawnee (from Waco to Kansas City, Sedalia, and St. Louis, Missouri), and the Western (from San Antonio, Texas, to Dodge City and then on to Fort Buford, at the fork of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, deep in the Dakota Territory). Between 1866, when Loving and Goodnight cut their trail, and 1886–87, when a single terrible winter nearly wiped out the range-cattle industry, many millions of beeves had been driven on these great trails.

WHILE THE SODBUSTERS RAISED WHEAT AND CORN, the trail drive was all about beef. But the industry also spawned the trail-drive cowboy, perhaps the single most beloved and mythologized worker in American history. He was America’s knight-errant; his image was noble, brave, and pure, surviving even the cynicism of the Gilded Age. The truth was that most cowboys were the poorest of the poor—many of them Confederate veterans dispossessed of family, friends, and all they had owned, and many others African Americans, Indians, and Mexicans, all standing on the lowest rungs of the American socioeconomic ladder. Nevertheless, the mythology proved resilient and well-nigh indestructible. It made exciting reading for consumers of the pulp fiction known as dime novels, brightening the dreary day of innumerable Eastern factory workers.

A photocrom print from Detroit Publishing Company, this image of a cowboy throwing a lariat dates from between 1898 and 1905, when the “Wild West” was rapidly slipping into memory and legend.

In the early days of the trail drives, cowboys drove the cattle directly to market, traversing great distances on horseback. As the nation’s western railroad network developed, the drives were shorter. Cattle were rounded up and driven to the nearest railhead. The Lincoln administration stimulated the building of western railroads for the same reason it encouraged western settlement through homesteading. The president wanted to expand the Union westward, and that meant promoting settlement, which, in turn, required reliable transportation. The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 and subsequent legislation granted huge tracts of land to the railroads, which used some of the land for rights-of-way and sold some of it to help finance rail construction. Federally backed loans were also made available, and in 1865, when even this generous funding proved inadequate to keep construction moving on the rail line to the Pacific, President Lincoln called on the Massachusetts congressman, Oakes Ames (1804–73). Known as the “Ace of Spades” because he had amassed his initial fortune by making and marketing shovels, Ames recruited investors—his fellow legislators, who were offered discounted stock—in a corporation created by Union Pacific Railroad vice president Thomas Durant and named after the company that had financed the French railway system a decade earlier, Crédit Mobilier. It was an offer that couldn’t be refused—a masterpiece of quasi-legal corruption created on the cusp of an age in which corrupt bargains would become business as usual. Crédit Mobilier, run by the directors of the Union Pacific, was paid by the Union Pacific to build the Union Pacific. The directors (who were the principal investors) made a profit on the operation of the railroad as well as on the cost of building the railroad. In essence, therefore, they were investing in themselves. This led to monumentally padded construction bills and a national scandal that, however, was not exposed until 1872. When the scandal broke, the Crédit Mobilier Scandal rocked the administration of Ulysses S. Grant and gave Oakes Ames a new nickname. No longer “King of Spades,” he was now “Hoax Ames.”

Oakes Ames, 1860. Known as the “Ace of Spades” because he had amassed his first fortune by making and marketing shovels, Ames masterminded Crédit Mobilier, the corrupt banking enterprise that financed the transcontinental railroad.

Scandalous though it was, Crédit Mobilier got construction of the transcontinental railroad moving. Under the leadership of Grenville Mellen Dodge, a U.S. Army engineer, the Union Pacific made prodigious progress, east to west, across the plains, despite the hostile climate and, often, hostile Indians, whose land was being gobbled up. Building from west to east, the Central Pacific moved more slowly through the mountainous terrain of the Sierras. Immigrant laborers—especially Irish on the Union Pacific and Chinese on the Central Pacific—were hired in unprecedented numbers. Casualties among the hard-driven work gangs were numerous, especially among Chinese laborers, who were put to work blasting out mountain passages.

Despite the profiteering, exploitation, corruption, and waste, on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit in Utah Territory, Leland Stanford drove the final ceremonial spike, painted shiny gold, into the last tie of America’s first transcontinental railroad. With this, the eastbound line of the Central Pacific was joined to the westbound rails of the Union Pacific. The ceremony did not go smoothly. As Chinese workmen, who had endured much persecution at the hands of their Caucasian employers and coworkers, lowered the final length of rail in place, a photographer hired to commemorate the moment hollered, “Shoot!” The workers instantly dropped the five-hundred-pound rail and ran.

Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10, 1869. Here the eastbound tracks of the Central Pacific were ceremonially joined to the westbound rails of the Union Pacific with a “Golden Spike” made of 17.6-karat copper-alloyed gold. The photograph shows CPRR’s Samuel S. Montague (center left) shaking hands with UPRR’s chief engineer, Grenville M. Dodge (center right).

THE “INDIAN WARS”

Immigrant laborers were not the only targets of racism in the westward rush. The story of the European settlement of America is also the story of Native American dispossession, displacement, and war. Virtually the entire span of the Gilded Age was marked by more or less continuous low-intensity warfare between the U.S. Army and many Indian tribes in the West. The most intense period of conflict began in 1866, when the Teton Sioux, the Northern Cheyenne, and the Northern Arapaho attempted to close the Bozeman Trail in Montana and Wyoming in a violent effort to stanch the flow of white settlers onto their lands. Beginning with the so-called War for the Bozeman Trail or Red Cloud’s War, the army waged fourteen major military campaigns, culminating in operations against the Sioux and ending in the Battle (or Massacre) of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 28–29, 1890.

In so many ways both tragic and immoral, United States Indian policy is a staggeringly complex subject far beyond the scope of a few paragraphs in a book. It is all too easy to broadly condemn the policy as genocidal. Without a doubt, some military operations targeted entire villages, combatant and noncombatant—men, women, and children. Nevertheless, if any single approach can be identified as national policy, it was not genocide but “concentration”—the gathering together and relocation of Indian groups on lands “reserved” for them. By law, once consigned and confined to a reservation, Indians became wards of the federal government, which pledged to provide them with rations and other necessary goods. The execution of official policy was, however, rife with corruption and incompetence, and, in many cases, reservation tribes suffered from privation, starvation, and deliberate abuse. These conditions incited rather than prevented “uprisings” and “rebellions.”

The United States Office of Indian Affairs issued this map of U.S. Indian reservations (highlighted in red) in 1892, the year after the Sioux Wars (1854–91) ended.

The objective of most military action against Indians during the Gilded Age was to force them onto reservations and keep them there. During 1870–90, the U.S. Army rarely topped 28,000 officers and men. It was essentially a frontier police force—poorly paid, poorly fed, poorly equipped, poorly trained, and often poorly led—very thinly spread across a vast area. The “enemy” it faced included—especially among the Plains tribes—warriors raised in a culture that valued and cultivated skill at arms, combat-effective horsemanship, and what today would be called guerrilla tactics. Possessed of a definite tactical edge, warrior tribes also had the advantage of defending a homeland they loved and knew intimately against “foreign” invaders. Threatened with impoverishment, dispossession, and death, the Indian warriors were highly motivated. This was in sharp contrast with the soldiers of the U.S. Army, who were often given ambiguous orders and who were themselves ambivalent about their mission. While some soldiers looked on Indians as a brutal, even subhuman enemy, many respected them and were revolted by the injustice and abuse to which poorly conceived and indifferently, incompetently, or maliciously executed federal policy had subjected them. Such ambivalence also reached to the highest levels of government. The halls of Congress rang with condemnation of military activity in the West, yet legislators struggled and failed to devise just alternatives.

For all their tactical advantages, Indian combatants were fatally handicapped in warfare by the very features of their culture, which prized individual strength, cunning, skill, endurance, courage, and honor. War chiefs were not generals. They did not command their fighters, but led them by charisma, reputation, and example. Rarely could large numbers of warriors be led in coordinated, disciplined operations. Even more rarely did tribes act with unity or form intertribal strategic alliances. Most of all, by the Gilded Age, the white population in the West massively outnumbered the Native American population—on average by a factor of ten. Against such demographic odds, no warriors could long prevail.

The western “Indian Wars” of 1866–90 were wars of attrition, and by the end of the nineteenth century, there were 187 reservations—181,000 square miles (468,788 km2) of land—in the United States. Of the 248,253 Native Americans counted in the 1890 U.S. Census, most were domiciled on reservations. This was the culmination of four centuries of Indian-white warfare in North America. And at this point, there arose from the despair and misery of the reservations a shamanistic Paiute prophet named Wovoka. Having spent part of his youth with a white rancher’s family, he was the product of both Native American and white Christian religious traditions. This moved him to prophesy to the reservation Indians the coming of a new world, in which only Indians dwelled and in which the bison were again plentiful on virgin plains. To promote the advent of this world, Wovoka urged all Indians to perform a sacred Ghost Dance and, in the meantime, to faithfully practice the ways of peace.

The Wounded Knee Massacre of December 29, 1890, made international news. This wood engraving, titled “The Ghost Dance of the Sioux Indians,” was published in the Illustrated London News on January 3, 1891.

Ghost Dancing soon swept through many of the Western reservations. While the Teton Sioux embraced the Dance, they rejected the ways of peace. Two Ghost Dance leaders among the Tetons, Short Bull and Kicking Bear, called for hastening the day of deliverance through a bloody campaign to obliterate the white man. For warriors in this cause, they fashioned a “ghost shirt,” which, they claimed, was impervious to white men’s bullets.

The Ghost Dance alarmed white Indian agents in charge of the reservations, who summoned army reinforcements. In a climate of increasing fear and distrust, the revered Hunkpapa Sioux chief Sitting Bull (c. 1831–90) took up the Ghost Dance religion. Knowing that many Sioux would follow Sitting Bull’s example, the agent in charge of the chief’s reservation dispatched Native American reservation police officers to arrest him on December 15, 1890.

No Native American was more famous or more revered—by whites and Indians alike—than the Hunkpapa Lakota chief Sitting Bull. He poses here adorned with a crucifix and holding a “peace pipe.” Five years later, he enthusiastically espoused the Ghost Dance religion—and was killed by Native American reservation police sent to arrest him on December 15, 1890.

The arrest went very badly. A riot broke out and, in the melee, whether deliberately or by accident, Sitting Bull was killed. Word of the “murder” spread like flame across the Sioux reservations, and a new war seemed inevitable. The most militant chiefs and warriors made a stand in a part of the Pine Ridge Reservation called the Stronghold. Chief Red Cloud, a Pine Ridge leader friendly to the whites, asked Spotted Elk (“Big Foot”), chief of the Miniconjou Sioux, to come to the reservation and use his influence to persuade the Stronghold party to surrender. Tragically, the army commander in the region, General Nelson A. Miles, knew nothing about this. All he knew was that the Sioux were near rebellion and that Big Foot, a prominent Sioux leader, was on his way to meet with the leaders of that rebellion. He therefore ordered his troops to pursue and intercept Big Foot and any other Miniconjous.

Renowned Western artist Frederic Remington published his depiction of “The Opening of the Fight at Wounded Knee” in the January 24, 1891, edition of Harper’s Weekly.

So, on December 28, 1890, a squadron of the 7th Cavalry located the chief and about 350 of his followers camped near a South Dakota stream called Wounded Knee Creek. By morning, some five hundred soldiers, under Colonel James W. Forsyth, surrounded Big Foot’s camp. In defiance, a medicine man, traditionally identified as Yellow Bird but probably Stosa Yanka (“Sits Up Straight”), began dancing, urging his people to fight. A shot was fired—no one knows by whom—and the soldiers opened up on the camp with deadly Hotchkiss guns, small rapid-fire cannon that delivered one 42-millimeter round per second. The troops mowed down men, women, and children, killing Big Foot and at least 153 other Miniconjous in less than an hour. Others, who were wounded, crawled or limped away and therefore went uncounted among the slain. Estimates put the total death toll at 300 of the 350 who had been camped at Wounded Knee Creek. Miles was appalled by Wounded Knee, but he nevertheless used the “battle” as the opening move in the final suppression of the Sioux “uprising.” The chiefs surrendered on January 15, 1891.

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

University of Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner delivered his famous paper on the significance of the frontier in American history just two years after the surrender of the Sioux. Based on the 1890 census, Turner concluded that the frontier had been fully settled—conquered, as it were—and therefore “closed.” He predicted that the “restless, nervous energy,” which had so long driven American westward expansion, would now “demand a wider field of exercise.” Without what he called the “safety valve” of an open frontier—his implied analogy to a steam engine was significant in an age of steam—American energy would propel expansion overseas. The United States would become an imperialist power.6

Recent historians question whether the frontier, as Turner imagined it, ever really existed. And if it did not exist, how could it “close”? Nevertheless, Turner was correct in his prediction that American policy would suddenly look beyond the ocean-bound borders of the United States. In February 1896, the Spanish government sent General Valeriano Weyler to restore order in Cuba, its increasingly rebellious island possession. Among the military governor’s first acts was to build “reconcentration camps” for the incarceration of rebels as well as other citizens accused of supporting or even sympathizing with the rebels. Although both U.S. presidents Grover Cleveland and his successor William McKinley stoutly resisted calls from some in Congress to intervene against Spanish “atrocity” in Cuba, American popular sentiment, whipped up by lurid stories of Spanish cruelty published in the rival New York papers of Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, at last moved McKinley to order the battleship USS Maine into Havana Harbor to protect American citizens and property there.

The onset of war fever in the United States was not exclusively caused by a humanitarian concern for Cuban suffering. By the late nineteenth century, large and powerful American business concerns had made major investments in the island, especially in sugar plantations. Revolutionary unrest posed a threat to these investments; however, a successful revolution, if properly supported by the United States, could create a nominally independent Cuban government that would be an obedient U.S. client. Alternatively, the United States might simply annex the island.

On February 9, 1898, Hearst created a sensation by publishing a purloined private letter in which the Spanish minister to the United States insulted President McKinley. With the nation now fully infected with war fever, news broke on February 15 that the armored cruiser Maine, moored in Havana Harbor, had suddenly exploded and sunk, with the loss of 266 crewmen. Today, most historians believe that the ship’s powder magazine spontaneously ignited through no hostile action, but a naval court of inquiry at the time concluded that the ship “was destroyed by the explosion of a submarine mine.”7 The court did not assign responsibility for the explosion—was it a rebel mine or a Spanish one?—but the Hearst and Pulitzer papers most certainly did. Each pointed a finger at Spain, and the United States soon rang with the battle cry of “Remember the Maine … to hell with Spain!”

Spain wanted no war, and obligingly began accelerating its withdrawal from Cuba. President McKinley therefore delayed a decision throughout the early spring, but, yielding at last to popular pressure, he requested congressional authorization for an invasion. The legislators gave him more than he asked for, voting to recognize Cuban independence from Spain. In response, Spain declared war on the United States, on April 24, 1898.

The diminutive U.S. Army was entirely unprepared to fight an “expeditionary campaign”—an overseas foray against a foreign adversary. But the far more formidable U.S. Navy was prepared, and it made the first move—not in Cuba, but in the Spanish-occupied Philippine Islands. After receiving word of the declaration of war, Rear Admiral George Dewey steamed his Asiatic squadron from Hong Kong to Manila Bay. On May 1, 1898, he fired on the Spanish fleet, destroying all ten ships in the bay. President McKinley dispatched eleven thousand troops to the Philippines, and that force, along with pro-independence Filipino irregulars commanded by Emilio Aguinaldo, defeated Spanish forces in Manila, the archipelago’s capital city, on August 13.

In the meantime, the U.S. Army delayed and blundered as it struggled to transport its soldiers from the American mainland to Cuba aboard a ragtag fleet of chartered commercial vessels. Yet once military action did start, the army moved decisively. On May 29, the U.S. fleet blockaded the Spanish fleet at Santiago Harbor on the eastern end of Cuba. The following month, seventeen thousand troops were finally positioned to invade Cuba at Daiquiri. Despite severe illness ravaging the ranks—Cuba was plagued by yellow fever—the invaders advanced on Santiago.

The Rough Riders pose around their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, atop San Juan Heights (also known as San Juan Hill or Kettle Hill), which they had captured on July 1, 1898, during the Spanish-American War. It was the make-or-break battle of the brief war’s even briefer land phase.

The regular army forces were supplemented by numerous hastily raised volunteer units, including the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry. When its commander, Colonel Leonard Wood, was given command of the entire 2nd Cavalry Brigade, his second in command, Theodore Roosevelt, assumed operational command of the 1st USVC, better known by its nickname, the Rough Riders. Roosevelt had stepped down from McKinley’s cabinet, in which he had been serving as assistant secretary of the navy, to accept a commission as lieutenant colonel, and he had personally selected the men of the Rough Riders. Thanks to a transportation snafu, the unit arrived in Cuba without most of its horses. So, when Roosevelt led the Rough Riders in the assault on Kettle Hill during the Battle of San Juan Hill on July 1, the attack was largely on foot. They not only took Kettle Hill, but fended off a determined counterattack. This victory enabled the American forces to surround Santiago de Cuba, and, from San Juan Heights (as the combination of San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill were called), the American forces attacked Santiago de Cuba while also firing on the Spanish cruiser fleet in the city’s harbor, which had been blockaded by the U.S. Navy. Under withering fire from the Heights, Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera decided that he had no choice but to run the blockade. In a four-hour naval battle, the American fleet destroyed all of Cervera’s ships while sustaining minor damage and the loss of just a single American sailor.

On August 12, Spain agreed to withdraw from Cuba and to cede Puerto Rico and the Pacific island of Guam to the United States. Formal peace negotiations in Paris resulted in Spain’s also selling the Philippine Islands to the United States for $20 million.

The United States set up a territorial government in Puerto Rico without much difficulty, but U.S.-Cuban relations proved far more tenuous. In 1899, President McKinley installed a military government and pondered annexation of Cuba, mainly to protect substantial American investments there.

Meanwhile, McKinley ran for reelection in 1900, winning a second term, with Theodore Roosevelt as his vice president. TR assumed the presidency himself on September 14, 1901, following McKinley’s assassination (see pages 310-11). In May 1902, the United States renounced annexation. Roosevelt withdrew federal troops from the island, and instead authorized Cuban leaders to draft a constitution for an independent Cuba. The document, which was subject to U.S. approval, included clauses establishing American military bases on the island and guaranteeing the right of the United States to intervene in Cuban affairs to “preserve” the island’s independence.

Theodore Roosevelt takes the oath of office as president of the United States, September 14, 1901, at the home of his friend, lawyer Ansley Wilcox, in Buffalo, New York. The ceremony took place hours after President William McKinley died of septic shock from wounds sustained during the Leon Czolgosz shooting.

“Roosevelt established a policy toward the Caribbean islands and Latin America that determined U.S. behavior in the region for decades to come.”

BECOMING A WORLD POWER

Riding a wave of popularity gained as a result of his heroism in what John Hay (U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom and then secretary of state) famously called “that splendid little war,”8 Theodore Roosevelt was elected president in his own right in 1904. As president, he took steps that certainly seemed to bear out Professor Turner’s predictions about the rise of American imperialism.

Roosevelt established a policy toward the Caribbean islands and Latin America that determined U.S. behavior in the region for decades to come. Known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, the policy called for the United States to act as an international police force in the region. In this way, for better or worse, the nation shunned the isolationism that had dominated its policies ever since George Washington warned against foreign entanglements. The nation began to assume a position as both a regional and a global power. The trend had begun during McKinley’s administration when, in January 1899, following the conclusion of the Treaty of Paris with Spain, the United States announced annexation of the newly acquired Philippines. Pro-independence Filipinos, under Emilio Aguinaldo, responded by proclaiming Philippine independence on June 12, 1898. This touched off the bitter Philippine-American War of 1899–1902, which brought an end to the First Philippine Republic and made the Philippines an unincorporated U.S. territory.

This portrait of the Empress Dowager Cixi was made c. 1890. It was hand-colored by painters of the Imperial Court. The regent who presided over Qing dynasty China from 1861 to 1908, she threw her support behind the so-called “Boxers” in the Boxer Rebellion. shooting.

In 1899, Secretary of State Hay proposed to the governments of France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Russia, and Japan that they all endorse an “Open Door Policy” (first suggested by a British customs official, Alfred E. Hippisley) with regard to China. The United States, all European nations, and Japan, he argued, should have equal access to Chinese trade. Although Japan balked, the proposal met with universal approval among the nations of the West, but China—the very subject of the policy—had not been consulted on the matter. An ancient empire in acute decay, China was torn by internal tensions and was barely held together by Cixi, the empress dowager. Seeing an opportunity to gain much-needed popularity by uniting the divided country against the foreigners, the empress dowager issued a proclamation on January 11, 1900, encouraging an uprising of a militant secret society called the Yihequan, the “righteous and harmonious fists,” which the Westerners called the “Boxers.”

In response to Boxer violence, the United States participated in a military coalition that also included England, France, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Italy, and Japan. Their mission was to protect their nationals in China by suppressing the so-called “Boxer Rebellion.” The coalition’s victory gained the United States little other than a measure of international prestige. As for China, the defeat of the Boxers brought down the Qing, or Manchu, dynasty, which had ruled since 1644. It would be decisively overthrown in the Chinese Revolution of 1911.

ROOSEVELT’S BOLDEST STEP TO PROMOTE AMERICAN IMPERIALISM was his conclusion of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, signed in 1903 and approved by the U.S. Senate in 1904, which cleared the way—diplomatically—for a canal joining the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Isthmus of Panama. The idea of building a canal to create a passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was not new. In the 1840s, the United States negotiated an agreement with New Granada (a nation consisting of present-day Panama and Colombia) for rights of transit across the Isthmus of Panama, which separates the Caribbean Sea from the Pacific Ocean. Although the isthmus jungle was dense and disease-ridden, it was nevertheless preferable to making the long and hazardous sea journey all the way down one side of the South American continent and up the other. Moreover, the 1849 California Gold Rush prompted the United States to fund the Panama Railroad across the isthmus. The ultimate goal—of the United States as well as Great Britain—was to build a canal across the isthmus. In 1850, the two nations concluded the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, agreeing that neither would assert exclusive control over the canal.

Drawing up an agreement for a canal was a long way from actually digging one. It was 1881 before a French firm, under the direction of Ferdinand de Lesseps, began work on an isthmus canal, only to quickly succumb to bankruptcy and the diseases endemic to the Panamanian jungle—yellow fever and malaria. Twenty years later, still bathed in the afterglow of victory in the Spanish-American War, Theodore Roosevelt’s State Department persuaded Great Britain to relinquish its claim to joint control of a Central American canal. In that same year, 1901, an American commission recommended building the canal in Nicaragua instead of Panama, but the New Panama Canal Company, successors to de Lesseps’s defunct firm, persuaded Roosevelt to build through Panama by offering the rights it held to the canal route not for the original asking price of $109 million, but for the bargain-basement price of $40 million. Congress authorized construction early in 1902, and the next year ratified the Hay-Herrán Treaty, by which Colombia (of which Panama was then a part) granted the United States a ten-mile (16-km) wide strip of land across the isthmus in return for a $10 million dollar cash payment and, after nine years, an annual annuity of $250,000.

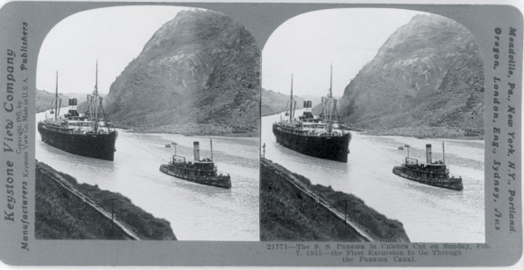

A stereograph of the SS Panama steaming through the Culebra Cut on February 7, 1915; it was one of the first passenger ships to pass through the completed Panama Canal.

Everything looked rosy until the Colombian Senate delayed ratification in the hope of increasing the price offered by the United States. Then, on August 12, 1903, that body flatly refused to ratify the treaty, partly over money, but mostly in response to a popular movement to resist “Yankee imperialism.” Roosevelt now turned to Philippe Bunau-Varilla, the French engineer who had worked on the original French canal project, joined the successor company, and gave the American president a good deal on the rights to the canal route. The president commissioned Bunau-Varilla to work with advocates of Panamanian independence to organize a revolt against Colombia. The Frenchman rallied and led a group of railway workers, firemen, and disaffected Colombian government officers and soldiers at Colón, Panama, in an uprising on November 3–4, 1903. The rebels proclaimed Panamanian independence. In the meantime, just offshore, the U.S. Navy cruiser Nashville, dispatched by President Roosevelt, interdicted an attempt by Colombian general Rafael Reyes to land troops to quell the rebellion.

On November 6, President Roosevelt officially recognized Panamanian independence and greeted Bunau-Varilla as minister from the new republic. With this new minister, Secretary of State Hay concluded the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty on November 18, which provided for the acquisition of a canal zone and the right to build and control a canal in exchange for the same monetary terms that had been offered Colombia. The U.S. Senate approved the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty in 1904, and actual construction began in 1906, after Colonel William Gorgas of the U.S. Army Medical Corps defeated the twin scourges of yellow fever and malaria by waging a successful war against mosquito infestation. In 1914, after eight years, almost $400 million, and the excavation of 240 million cubic yards (183,493,166 m3) of earth, the Panama Canal was opened to shipping. The magnitude of this project, which changed the face of the Earth itself, was extraordinary. For Theodore Roosevelt, that was precisely the point. A great world power should take on nothing less.