CHAPTER 14

THE PROGRESSIVES

The victory of dark horse nominee James A. Garfield over James G. Blaine on the thirty-sixth ballot of the incredibly rancorous Republican National Convention of 1880 marked the victory of the party’s progressive wing (this faction had yet to earn a capital “P”) over the Stalwart faction led by New York senator Roscoe Conkling, the nation’s preeminent machine politician. Garfield represented social change and clean politics. He was a major advocate of efficient government, including civil service reform, which was intended to replace political patronage (the “spoils system”)—by which government appointees and employees were chosen for their demonstrated party loyalty—with nonpartisan, merit-based appointments. Conkling represented the old way of doing things; Garfield the new and “progressive” approach, which was widely seen as part of the modernization trend evident in all aspects of American life during the Gilded Age.

After Charles J. Guiteau gunned down the president at the start of his fifth month in office (see chapter 13), he proclaimed to police, “I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts! I did it and I want to be arrested! Arthur is president now!”1 Vice President Chester A. Arthur (1829–86), a Conkling protégé and, judging by his record, a machine hack, was indeed a Stalwart. Those who believed that Garfield’s election meant real change for the nation were heartbroken. All they could do was pin their fragile hopes on the wounded man’s recovery, and when Garfield succumbed to infection on September 19, 1881, their hopes vanished. For Arthur was indeed president now.

Bloated and bewhiskered, Vice President Chester A. Arthur looked every inch the comfortably corrupt Republican “Stalwart.” On the death of President James A. Garfield, Arthur stunningly defied expectations by carrying out the slain president’s program of reform. No American political figure has ever redeemed himself more remarkably.

A soft, round man, whose mutton chop whiskers only drew more attention to his turkey neck, Chester “Chet” Alan Arthur looked every inch the well-fed part of the typical Stalwart politician. Doubtless, with his succession to office, Conkling and his cronies looked forward to unexpected good times. But Arthur himself was anything but exultant. When news of the president’s death reached him, all he could manage to stammer was “I hope—my God, I do hope it is a mistake.”2 His sole function as Garfield’s running mate had been to balance the ticket. Garfield was a Midwestern progressive, Arthur an Eastern Stalwart. Mostly, he was a functionary, obedient and submissive. In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes, in a rare spasm of reform, had fired Arthur from his lucrative post as New York customs collector. Since then, presumably fearful of losing another patronage sinecure, he did whatever Conkling told him to do.

Miraculously, on the death of the president, Chet Arthur found within himself a reserve of character he had never before tapped. Installed in the executive mansion, he did not miss a beat in taking up the cause of reform exactly where the slain president had left it. He morphed from Stalwart to progressive. His signal action was to sign into law the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883, which laid the foundation of the modern nonpartisan, merit-based civil service system. This sent shock waves through Stalwart ranks. Of subtler significance was his espousal of naval reform by authorizing the building of three steel “protected cruisers,” Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago, cutting-edge forerunners of the modern battleship and the heralds of another progressive theme—the United States’s claim to a position as world power.

DOWN ON THE FARM

The social and economic abuses rampant in the Gilded Age—the reign of the robber barons (see chapter 3), the abuse of immigrants (see chapter 6), the oppression of labor (see chapter 7)—had all triggered calls for reform, sometimes violent reform. Discrete acts of reform were generally associated with the cities, but the broader movement toward large-scale political reform began during the 1880s and the early 1890s with the complaints of the nation’s beleaguered farmers.

The farmers felt left out. After the Civil War, the industrialists and financiers usurped from them the language by which they had formerly defined themselves. Democratic ideals, such as democracy, liberty, equality, opportunity, and individualism, which Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson had associated with the noble agrarian—the independent farmer who boldly pushed American civilization to the western frontiers of the continent—were now the terms by which Rockefeller and Carnegie and Morgan and others of their frock-coated ilk pushed a program of laissez-faire economic policies that effectively put government in the hands of big capital.

The photographs of Solomon Butcher chronicle the hard life of the prairie sodbuster, far from the gilded cities of the late nineteenth century. Here are the Rawlings, “a farming family of Custer County, Nebraska,” 1886.

In truth, industry was invading agriculture with more than words. Innovative machinery, including sulky plows with wheels and a driver’s seat, corn planters, end-gate seeders, spring tooth rakes, binders, threshing machines, hay balers, hoisting forks, and corn shellers, had been essential to the recovery (still very imperfect) of Southern farmers from Civil War devastation. Such machinery was even more critical to farmers on the frontier, especially on the Plains, where the unyielding soil did everything possible to defeat mere human muscle. In the days of Jefferson and Jackson, self-sufficiency may have been for farmers both the idea and the rule. In the Industrial Revolution, however, farmers produced not for themselves and the villages surrounding them, but for “the market” as a whole, and the increased yields, combined with innovations in communications and transportation, ended agrarian isolation forever. The farmer now had access to a national, even international market, but was also obliged to compete in that market without government protections or regulation over production. Lacking the advantages of an urban tycoon’s capital reserves, the farmer found himself bound to the wild swings of business and price cycles over which he had no control and into which he had very little insight. The farmer did not actually see this marketplace, but he was keenly aware of its impact on him. Even as his productivity increased, the prices he received for his commodities declined. There was terrible injustice in a system that earned him less the harder he worked and the more he grew. Moreover, the less he earned, the more he needed to spend to increase production. The gap between income and expenses widened with each passing season, and soon the farmer became a debtor, forced to mortgage his land or borrow against future harvests to cover debts.

With many of the same business forces that impinged on urban labor now encroaching on them as well, farmers across the country overcame their bias toward going it alone and began forming unions and alliances that passed through several incarnations before emerging in 1891 as the People’s Party, which was also called the Populist Party or simply the Populists. The two most important Populist precursor parties, the Farmers’ Alliance (1870s) and the Greenback Party (1874–89), were largely rural and agrarian. A third forerunner was made up of an amalgam of urban labor groups, the most important of which were four small parties with the word Labor in their names: Union Labor Party, United Labor Party, Industrial Labor Party, and Labor Reform Party. These drew mainly on members of the Knights of Labor union and disaffected members of the waning Greenback Party. This agglomeration of political organizations became regional, rather than national, election influencers, electing a number of candidates to local offices in 1886.3

“Gift of the Grangers,” an elaborate chromolithograph of c. 1873, decorated the farmhouses of thousands of members of the Grange during the heyday of this powerful agricultural advocacy and lobbying organization.

In addition to the Knights of Labor, the National Grange of the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry—more simply called the Grange—a fraternal order of farmers founded in 1867, had a major role in expanding the Populist Party. As for the Greenback Party (also known as the Greenback Labor Party), its name reveals the chief concern of its members. “Greenbacks” were the paper currency, not backed by gold, issued during the Civil War. Greenbacks were intended to increase the money supply to facilitate payment of the tremendous expenses incurred by the war. The driving concern of the Greenback Party was its opposition to the postwar return to a fully gold-backed monetary system because it contributed to deflation and a lowering of prices paid to farmers. Unbacked currency, the party believed, would be a boon to farmers by raising prices and making their debts easier to pay. From the perspective of the government, greenbacks had been strictly an emergency expedient during the Civil War. From the perspective of farmers in dire straits, this fiat money represented salvation. For them, the “emergency” had never ended.

On February 22, 1892, a total of 860 delegates from twenty-seven reformist organizations, including the National Farmers’ Alliance, the Industrial Union, the Knights of Labor, and others, met in St. Louis at what was billed as the Industrial Conference. With 246 delegates between them, the National Farmers’ Alliance and the Industrial Union formed a single bloc and proclaimed their support for the new People’s Party, which many persisted in calling the Populist Party. Under either name, it was the most radical third party in American history.

The Populist Party proposed some of the most radical economic and political innovations of the late nineteenth century. Call it socialism “lite”: government ownership of railroads and utilities, a progressive (graduated) income tax, voting by secret ballot (which was not universally adopted in the United States until 1891), women’s suffrage, and Prohibition. The central issue, however, was the “the free coinage of silver,” which was the use of both silver and gold (“bimetallism”) as currency at the ratio of 16:1—sixteen ounces (454 g) of silver assigned the value of one ounce (28 g) of gold. The idea was to inflate the value of money to raise farm and other commodity prices, free up credit, and increase employment. Doing this also meant an end to unregulated laissez-faire economics and required federal manipulation of the money system. Such intervention rested on the proposition that government properly had some responsibility for the social well-being of its citizens. Urban—especially East Coast—capitalists were terrified.

The People’s Party held its first national convention on July 4, 1892, in Omaha, Nebraska, nominating former Iowa congressman James B. Weaver as its presidential candidate. Both Weaver and the Republican nominee that year, James G. Blaine, lost to Democrat Grover Cleveland. Undaunted, the Populists continued to promote a program of radical reform. The new party filled the vacuum between the Democrats and the Republicans and narrowed the gaps separating regions of the country, races, and classes. For the first time in American political history, this third party staked out viable common ground on which reformers of every stripe could join hands. By far, the widest gulf bridged was the long-standing division between the interests of farmers and labor. In 1896, the Populists took what they saw as their best shot at gaining national power. They showed up in full force at the Democratic National Convention in July 1896 in Chicago and snatched the party’s nomination from Cleveland, who was looking to run for an unprecedented third term. In his place, the Populists offered William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925), congressman from Nebraska’s 1st District, and already nationally famous as the “Boy Orator of the Platte.”

“For the first time in American political history, this third party staked out viable common ground on which reformers of every stripe could join hands.”

The nation was in the depths of what was still being called the Panic of 1893, but which had become an intractable depression, the like of which would not be seen again until the Great Depression of the 1930s. It had begun when the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad went bankrupt, triggering the biggest sell-off the New York Stock Exchange had experienced up to that point. Banks called their loans. Credit dried up. The Erie, the Northern Pacific, the Union Pacific, and the Santa Fe railroads all failed, one after another. Mills, factories, furnaces, and mines shut down everywhere. Before it was over in 1897, roughly 500 banks had failed, at least 15,000 businesses were shuttered, and uncounted numbers of farms were simply abandoned. In 1892–93, the unemployment rate shot up from 3 percent to 11 percent. In New York City alone, it hit a staggering high of 35 percent.4

Amid financial chaos and sheer terror, the Populist agenda, which many had dismissed as the ravings of a lunatic fringe, now appeared supremely rational. True, the notions of a progressive income tax and votes for women were still too much for most voters to swallow, but they were now at least open to serious public discussion. In droves, voters exited the Democratic as well as the Republican mainstream and embraced Populism. Looking to save their party, the Democrats, jealously eying the outflow of votes, summarily ejected the conservatives, the so-called Bourbon Democrats, and that meant ditching President Cleveland himself. Invited to the convention rostrum, William Jennings Bryan electrified the Democratic National Convention with a speech advocating the whole Populist agenda, including bimetallism. “I would be presumptuous, indeed, to present myself against the distinguished gentlemen to whom you have listened if this were a mere measuring of abilities,” Bryan quietly began, “but this is not a contest between persons. The humblest citizen in all the land, when clad in the armor of a righteous cause, is stronger than all the hosts of error. I come to speak to you in defense of a cause as holy as the cause of liberty—the cause of humanity.” He later made the case for a second American revolution:

It is the issue of 1776 over again. Our ancestors, when but three millions in number, had the courage to declare their political independence of every other nation; shall we, their descendants, when we have grown to seventy millions, declare that we are less independent than our forefathers? No, my friends, that will never be the verdict of our people. Therefore, we care not upon what lines the battle is fought. If they say bimetallism is good, but that we cannot have it until other nations help us, we reply that, instead of having a gold standard because England has, we will restore bimetallism, and then let England have bimetallism because the United States has it. If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we will fight them to the uttermost.

And, with this, he let fly his final arrow: “Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests, and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: ‘You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.’”5 Nor did he rely on words alone. Pressing the fingers of both hands to his temples, he suddenly extended both arms outward from his body in a pose of crucifixion. He stood thus for some five seconds, while the audience, transfixed, was silent. He then lowered his arms, stepped down from the podium, and, as he did, the applause began, slowly, before erupting in delirium.

That delirium, however, did not translate into a victory against Republican William McKinley, who received 271 electoral votes to Bryan’s 176. While Bryan remained a popular figure in American politics and a presidential hopeful in 1900 and 1908, his defeat by McKinley in 1896 heralded the demise of the Populist Party. Bryan became a successful lecturer—mostly on subjects of Christianity and general morality—from 1900 through 1912 on the Chautauqua circuit. A phenomenon of the Gilded Age, the Chautauqua movement began in 1874 with a camp meeting organized by Methodist minister John Heyl Vincent and a businessman, Lewis Miller, on the shore of Chautauqua Lake in upstate New York. It spawned Chautauqua assemblies nationwide, which variously featured speakers, educators, musicians, preachers, and others in what is best described as a mass, popular, adult-education movement.

Bryan kept his hand in politics and supported Woodrow Wilson for president in 1912, becoming his secretary of state in 1913 but resigning two years later in protest against what he deemed the president’s drift toward entry into the Great War (World War I). At the end of his career and his life, Bryan passionately advocated for Prohibition and against the teaching of Darwinian evolution in public schools. This culminated in his testimony for the prosecution in the sensational Scopes Trial of 1925, in which Tennessee schoolteacher John T. Scopes was convicted of violating state law by teaching human evolution. Bryan was humiliated on the witness stand by Scopes’s attorney, the legendary Clarence Darrow, and died five days after the trial ended. The often-brilliant, always incendiary journalist, social critic, and self-appointed enemy of intolerance H. L. Mencken gleefully published Bryan’s obituary the day after the man’s death. He claimed that Bryan had “committed suicide” upon “Clarence Darrow’s cruel hook,” having “writhed and tossed in a very fury of malignancy, bawling against the veriest elements of sense and decency like a man frantic. … He staggered from the rustic court ready to die, and he staggered from it ready to be forgotten, save as a character in a third-rate farce, witless and in poor taste.”6 Except for Mencken’s Baltimore Sun, the nation’s newspapers reported the cause of Bryan’s death as “apoplexy,” a stroke, but it is most likely that diabetes was a contributing factor.7

FROM POPULISM TO PROGRESSIVISM

The Populist Party came to an end, but Populism did not so much die as it was remolded into a more cohesive progressive movement, which may be described as Populism ratcheted up from the farmers and laborers to the middle class. There was less emphasis on improving the lot of the masses than on raising the level—and the moral “tone”—of American civilization. Progressivism was associated with “progress” in all its guises, including an embrace of education and science as applied to creating a more just and a more efficient society. “Taylorism,” the high-efficiency management ideas Frederick Winslow Taylor published in his 1911 Principles of Scientific Management, transformed the American workplace as well as the bureaucracies of American government (see chapter 4).

In the run-up to the founding of a Progressive Party in 1912, the most important reforms in national politics and policy were currency reform and civil service reform. The Greenback Party and, later, the bimetallism advocated by Bryan, led to pressure for congressional action. The admission of six new Western states in 1889–90, during the administration of President Benjamin Harrison, tipped the balance toward demand for silver coinage to increase the money supply. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 required the U.S. Treasury to purchase 4.5 million ounces (128 million g) of silver per month to be converted into coins and silver certificates (paper money backed by and redeemable as silver). This emboldened Bryan in 1896 to ask for even more—a transition from the gold standard to a combined gold and silver standard, which would release yet more money into the economy. But, in electing McKinley, thereby installing in the White House a more probusiness administration in 1896, a substantial majority of voters rejected this lurch toward Populism.

As it turned out, the election of 1896 did not swing the policy pendulum permanently back toward the era of the robber barons. Under Theodore Roosevelt, who would succeed the slain McKinley in 1901, Populism would continue to morph into progressivism, and big business would find itself facing a new reformer. The reforms President Roosevelt championed had their predicates in two important pieces of Gilded Age legislation. The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 was passed in response to abuses by railroad monopolies, including price fixing among monopolistic rivals and discriminatory shipping rates that forced farmers to use grain elevators and other storage facilities controlled by particular railroad operators. The act required “charges made for any service rendered or to be rendered in the transportation of passengers or property … to be reasonable and just” and prohibited as unlawful “every unjust and unreasonable charge.”8 What this meant was that the federal government now had regulatory and oversight power over interstate commerce. The idea that government had a proper role in the regulation of business was thus laid as a cornerstone of future progressivism. Three years later, another law, the Sherman Antitrust Act, was passed, barring businesses from employing monopolistic practices or otherwise acting in restraint of trade, including taking unfair advantage of competitors.9 With this, the reign of laissez-faire big business was doomed—at least once a president willing to wield the government’s new powers came into office.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act (1890) put more silver coins and paper “silver certificates” into circulation, creating an inflationary “flood” that (according to this 1893 Puck cartoon) threatened to drown “Business Interests.” Uncle Sam comes to the rescue with an effort to climb the rope of “Public Opinion” to the high ground of a proposed repeal of the act.

In the meantime, civil service reform took a giant—and unexpected—leap in 1883 when Chester A. Arthur, catapulted into the presidency by Garfield’s assassination in 1881, supported the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act.10 The act was the beginning of the end of the old spoils system, by which nonelective government positions were distributed to party faithful as the “spoils” of electoral victory. Under the act, the United States Civil Service Commission was established to create and administer a civil service system to ensure that government personnel would be hired—and maintained and promoted or dismissed—on the basis of merit and performance, not because of political connections. The process of reform extended throughout the last twenty years of the Gilded Age, so that, by the turn of the century, approximately half of all federal employees were classified under civil service rules. Today, the overwhelming majority of unelected government employees are civil servants, although high-level policy positions continue to be filled by political appointees serving at the pleasure of the president.

ROUGH RIDER

Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio was one of the Republican “Old Guard”—an updated name for the faction called the Stalwarts twenty years earlier. When word reached him of the death of President McKinley on September 14, 1901, he cried out: “Now look! That damned cowboy is president of the United States.”11

He was referring, of course, to Theodore Roosevelt (1857–1930), who had, in fact, owned and personally worked a ranch in the Dakota Territories, but who was far better known for his relentlessly reformist record as a former member of the U.S. Civil Service Commission and the former president of the New York City Police Board of Commissioners. As governor of New York, before being tapped as McKinley’s second-term running mate in 1900, he introduced bold reforms in Albany. His energy and zeal were inexhaustible, and he would now apply both to the presidency. The Old Guard—everywhere—had reason to mourn the passing of McKinley.

As a progressive rather than a Populist, TR saw capitalist enterprise as the great and essential engine of the American economy and the American claim to economic and political leadership in the world. Nevertheless, he believed that the Old Guard Republican policy of uncritical support for laissez-faire business, even at the expense of labor and consumers, was not only bad for the nation, but ultimately fatal for the party. Business should be allowed to prosper, but under the watchful eye and regulatory hand of enlightened government.

Enlightened government—that, Roosevelt believed, could not be entrusted to the legislative branch. He resolved to end the Gilded Age reign of weak presidents by refashioning the presidency as the office of the people’s steward and tribune. Persuaded that too many members of Congress were in the pocket of big business and no longer represented the interests of the people, Roosevelt decided that he would both represent and guide the electorate. He therefore proclaimed what he termed a “New Nationalism,” in which the entire administrative machinery of the federal government would be geared toward promoting the public welfare. The states would be obliged to subordinate themselves to federal direction, and the president, as tribune for all the people, would lead Congress in crafting laws to serve them.

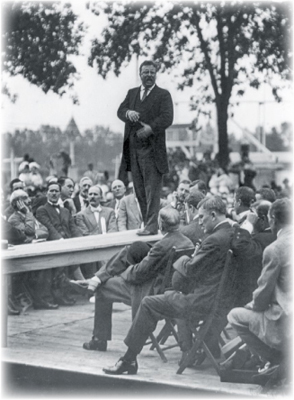

President Theodore Roosevelt speaks at Freeport, Illinois, June 3, 1903, at the dedication of a monument to the second of Abraham Lincoln’s antislavery debates with Stephen A. Douglas. TR saw in Lincoln an ancestor in the cause of progressive reform.

Theodore Roosevelt packaged his progressive domestic agenda as the “Square Deal.” This included policies intended to curb the abuses of big business, especially monopolistic trusts, while also curbing the “outrageous” demands of radical labor. The newspapers hailed the president as a “Trust Buster” after his Department of Justice used the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 to force the breakup of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. At the same time, TR became the first president to proactively engage with labor by articulating labor’s legal rights as well as the limits of those rights. When necessary, he intended to intervene in labor-management disputes directly.

Among the most innovative and far-reaching of Roosevelt’s progressive reforms was his promotion of what was called, in the early twentieth century, “conservation”—today’s environmentalism. He championed an array of conservation legislation, including laws that set aside millions of acres of national forest to be protected either entirely or in part from commercial exploitation. His signature environmental legislation, the 1906 American Antiquities Act, established 150 national forests, fifty-one federal bird reserves, four national game preserves, five national parks, and eighteen national monuments. When his legislative zeal collided with the interests of farmers and industrialists, their lobbyists goaded Congress into enacting legislation in 1908 that transferred from the president to the Congress authority to create future national forests in some Western states. Undaunted, Roosevelt resorted to executive orders to instantly implement many of his conservation initiatives. In all, by law and by executive action, TR protected some 230 million acres (92 million ha) of public land during his presidency.12

On the world stage, Roosevelt bolted far ahead of Congress. While many presidents before him deferred to the legislature on key matters of foreign policy, TR assumed quasi-autocratic authority in matters of international relations, barely consulting with Congress. In his first annual address to Congress on December 3, 1901, he asserted that U.S. victory in the Spanish-American War (1898)—in which he had fought as lieutenant colonel of the legendary Rough Riders—meant that the United States now had “international duties no less than international rights.”13 Roosevelt’s redefinition of America as a world power would find expression in the nation’s 1917 entry into the Great War that had begun in 1914—when most Americans disdainfully called it the “European War.” Except for a span of isolationist Republican administrations during the 1920s and into the first three years of the 1930s, the United States would henceforth define itself as a great world power with great privileges and even greater responsibilities.

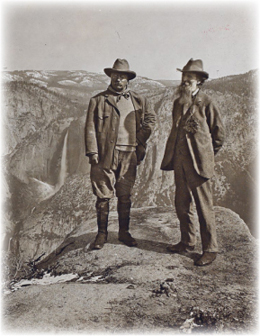

A stereograph of President Roosevelt with Sierra Club founder John Muir, the Scottish-American naturalist instrumental in molding the president’s passion for the environment. This photograph was made at Glacier Point on a trip to Yosemite Valley, California, in 1903.

TR’S WAR OF 1912

As unconventional as Theodore Roosevelt was, he could not bring himself to break the tradition, started by George Washington, that no president would serve more than two terms. In 1908, there was no Twenty-Second Amendment to legally bar a president from seeking a third term, and, had he chosen to run, TR could have argued that it would be, after all, only his second elected term. In the end, he erred on the side of tradition and bowed out of consideration, deferring, however, to a candidate he himself handpicked to succeed him. William Howard Taft (1857–1830), TR’s secretary of war, was a committed progressive, and the president trusted him to carry forward the executive agenda he had established. Indeed, Taft dutifully laid down a full program for legislative action—some of which was enacted—but Taft, ponderous in deliberation as he was ponderous in weight (at 355 pounds [161 kg], he was by far the heaviest U.S. president), never goaded Congress, let alone defied it, as Roosevelt often had. Nor did he go around the legislature to use what TR famously called the executive’s “bully pulpit” to appeal directly to the people. Taft preferred to quietly propose legislation, present a logical argument for it, and then let Congress take its course.

Taft was not a great president, but he was an admirable chief justice of the Supreme Court, to which President Warren G. Harding appointed him in 1921. It was a job Taft relished far more than the presidency. Here, an undated photograph of Taft.

That course was not uniformly progressive, and in March 1910, Republican progressives in the House united with Democrats to strip Speaker Joseph Cannon, an unapologetic Old Guard Republican, of much of his power. This created legislative chaos that a President Teddy Roosevelt would have seized on to aggrandize executive power. But Taft wanted no such thing, and the result was a dysfunctional Congress, a drifting presidency, and a profoundly discontented electorate.

As for Roosevelt, he had bitter reason to regret his decision against seeking a third term. In 1912, Taft was on course for the Republican nomination to run for a second term. Roosevelt was undecided about challenging him—until Robert M. LaFollette, senator from Wisconsin, a man who had earned his progressive reputation as the daringly innovative governor of Wisconsin, challenged Taft. Believing that neither Taft nor LaFollette could prevail against Democrat Woodrow Wilson, Roosevelt rather belatedly announced “My hat’s in the ring. The fight is on, and I’m stripped to the buff.”14 In the primaries, TR emerged the clear victor, winning 278 delegates to Taft’s 48 and LaFollette’s 36. But because thirty-six states did not hold primaries, the convention was very much up for grabs. Although most of LaFollette’s delegates deserted him for Roosevelt, Taft nevertheless prevailed. Roosevelt charged that some of the Taft delegations had been seated fraudulently, and he walked out of the convention, declaring himself the presidential candidate of the brand-new Progressive Party, which he and his supporters founded right then and there. It was quickly nicknamed the Bull Moose Party after newspapers reported that candidate Roosevelt said he now felt “fit as a bull moose.”15

In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt was the presidential nominee of the Progressive Party, but when he told reporters that he felt “fit as a bull moose,” the party got a more colorful nickname that stuck, and TR became the “Bull Moose candidate.”

The Bull Moose platform is remarkable, even by modern standards:

• Political campaign contribution limits

• Disclosure of contributors to political campaigns

• Registration of lobbyists

• All congressional committee proceedings to be recorded and the minutes published

• Creation of a National Health Service

• Creation of “social insurance,” to provide for the elderly, unemployed, and disabled

• Limits on legal injunctions against labor strikes

• A minimum wage law for women

• An eight-hour workday

• Creation of a federal securities commission

• Farm relief programs

• Creation of a fund for workers’ compensation for work-related injuries

• A federal inheritance tax

• Women’s suffrage

• Popular election of senators (at the time, senators were appointed by state legislatures)

• Required primary elections for state and federal nominations16

It was a tough three-way campaign that year among Taft, Wilson, and Roosevelt—who very nearly didn’t survive it. On October 14, 1912, while TR was campaigning in Milwaukee, John Schrank, a local saloonkeeper by trade, shot the candidate at close range just as he was about to enter an auditorium to deliver a speech. The bullet hit Roosevelt’s steel eyeglass case in the inner pocket of his frock coat, penetrating it before tearing through the fifty-page manuscript of the evening’s speech, which was folded—thereby doubling its thickness—in the same coat pocket. These two obstacles significantly slowed the projectile, which nevertheless lodged in Roosevelt’s capacious barrel chest.

Roosevelt neither lost consciousness nor was even knocked off his feet. A renowned big game hunter, the Bull Moose candidate pronounced the wound minor, mainly because he was breathing well and was not coughing up any blood. Waving off everyone’s insistence that he, for the love of God, allow himself to be rushed to the hospital, Teddy Roosevelt insisted on delivering a speech.

Taking his place at the podium, he dramatically threw open his coat and vest to reveal his blood-soaked shirt.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he began, “I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.”17 He then spoke for an hour and a half before finally consenting to go to the hospital. There, x-rays revealed that the bullet had passed through three inches (7.5cm) of chest tissue, coming to rest in a muscle before it could hit any vital organs. Surgeons decided to leave the slug where it was, rather than risking an operation to remove it. TR carried the bullet for the rest of his life.

Shot in the chest at point-blank range on October 14, 1912, just before he was to deliver a campaign speech in Milwaukee, Roosevelt refused medical attention and delivered a ninety-minute oration before he allowed himself to be hospitalized. This X-ray shows the bullet lodged in the candidate’s chest (second arrow from bottom). It remained there for the rest of his life.

Hospitalization took Roosevelt off the campaign trail for a week, during which both Taft and Wilson suspended their campaigns, agreeing that it was the only gentlemanly thing to do. In the end, TR drew 27 percent of the popular vote, to 42 percent for Wilson and a miserable 23 percent for the incumbent Taft. Socialist Eugene V. Debs polled 6 percent. Roosevelt’s tally remains the best third-party performance in American electoral history. While his defeat marked the end of the Progressive Party as a significant political force, it hardly signaled the end of Progressivism. On the contrary, Woodrow Wilson, a prolific author of works on American political history, a distinguished PhD professor of political science, former president of Princeton University, and reform governor of New Jersey, was perhaps the ultimate Progressive and, in every possible way, the exact opposite of the old-style Gilded Age politician.