CHAPTER 5

CHOOSING THE RIGHT VISUAL

This chapter introduces the common types of visuals used to communicate data in a business setting, discusses appropriate use cases for each, and highlights their use through examples built from the catalog of charts available in Tableau. You will also learn techniques to help you assess when to use these graphs, when to avoid certain types of charts, and how to generate them according to best practices, along with some of the special features in Tableau designed to help you get the most from your visual.

When it comes to visualizing data, there is no shortage of charts and graphs to choose from. From traditional graphs to innovative hand-coded visualizations, there is a continuum of visualizations ready to translate data from numbers into meaning using shapes, color, and other visual cues. However, each visualization type is intended to represent different types of data in specific ways to best represent its insight. Let’s look at seven of the most common visualization types to help you choose the right chart for your data.

The Bar Chart

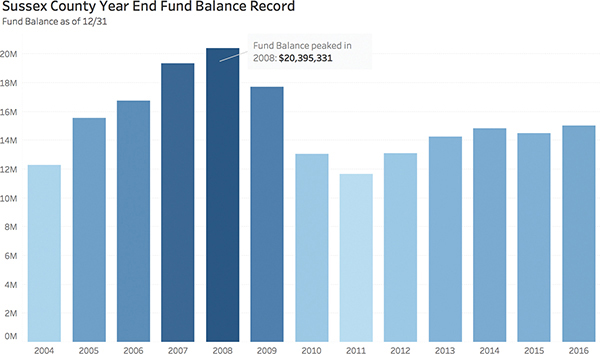

A traditional favorite, the bar chart is one of the most common ways to visualize data. It is best suited for numerical data that can be divided into distinct categories to compare information and reveal trends at a glance (see Figure 5.1).

An old classic, there are a few ways to spice up a bar chart.

![]() Bars can be oriented on the vertical or horizontal axis, which can be helpful for spotting trends.

Bars can be oriented on the vertical or horizontal axis, which can be helpful for spotting trends.

![]() Additional layers of information can be added using clustered bars or by stacking related data.

Additional layers of information can be added using clustered bars or by stacking related data.

![]() Color can be added for more impact or to overlay for immediate insight.

Color can be added for more impact or to overlay for immediate insight.

![]() Trend lines and other annotations can be added to highlight important data points.

Trend lines and other annotations can be added to highlight important data points.

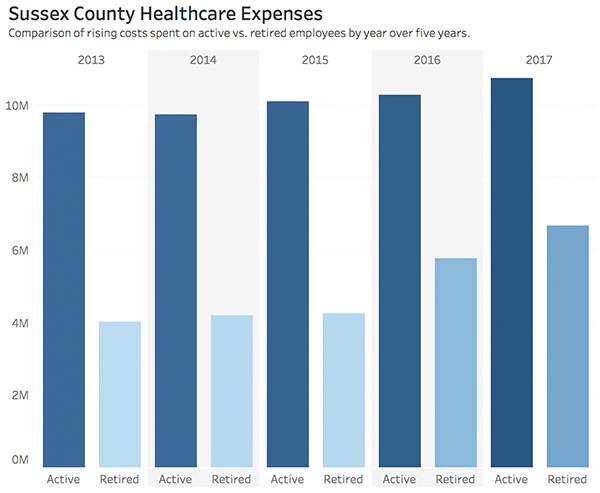

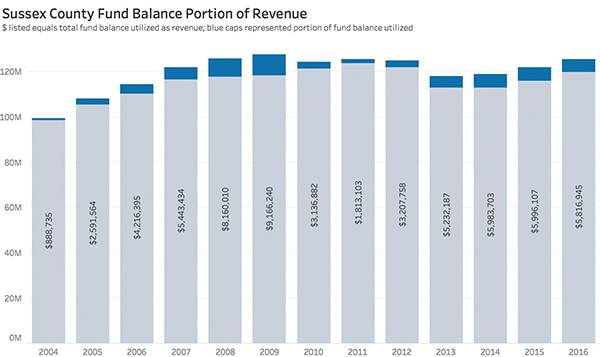

![]() Use side-by-side or stacked bars (see Figure 5.2) to give depth to your analysis and answer multiple questions at once.

Use side-by-side or stacked bars (see Figure 5.2) to give depth to your analysis and answer multiple questions at once.

![]() Bar charts can be combined with maps or line charts to act as filters that correspond to different data points as they are selected.

Bar charts can be combined with maps or line charts to act as filters that correspond to different data points as they are selected.

![]() Finally, multiple bar charts could be set on a dashboard to help viewers quickly compare information without navigating several charts.

Finally, multiple bar charts could be set on a dashboard to help viewers quickly compare information without navigating several charts.

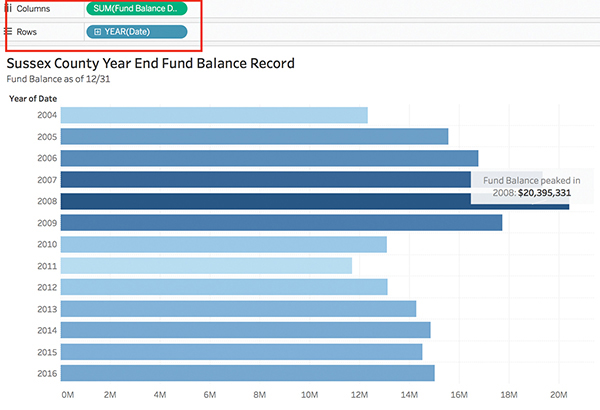

Figure 5.1 This simple, classic bar chart with color gradient shading and a point annotation compares the year end balance for Sussex County, NJ over a period of 13 years.

note

All the charts and graphs created in this chapter are made from real data. You can work with these datasets yourself by downloading the raw or cleaned data files and accompanying Tableau workbooks from www.visualdatastorytelling.com.

Figure 5.2 Alternative bar charts: a side-by-side bar chart with color gradient shading and a stacked bar chart with labeled and banded columns.

Tableau How-To: Bar Chart

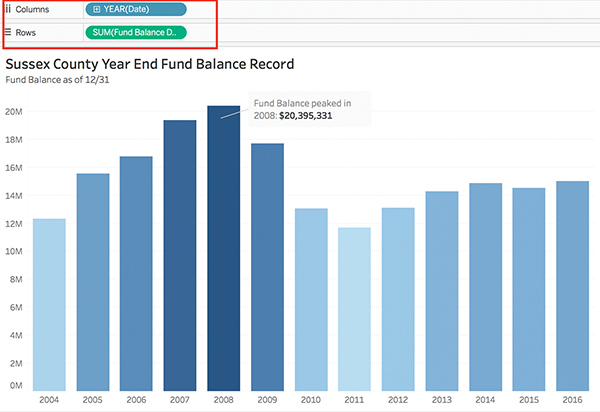

To begin a vertical bar chart in Tableau, place a dimension on the rows shelf and a measure on the columns shelf (or vice versa to create a horizontal bar chart—place a measure on the rows shelf and a dimension on the columns shelf as in Figure 5.3). You will notice that the Bar mark type is already selected on the Mark card. Tableau automatically selects this mark type when the data view matches one of the two field arrangements mentioned previously. From here, you can add additional fields to these shelves and further modify your bar chart as desired.

Figure 5.3 You can create vertical or horizontal bar charts by rearranging measures and dimensions on the rows and columns shelves. However, pay attention to how many bars you have on a horizontal bar chart to avoid the Moire effect (see Chapter 6).

tip

Instead of manually rearranging pills on the shelves, you can also use the Swap Rows and Columns button on the toolbar to rearrange rows and columns and toggle between views (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 The Swap Rows and Columns button.

The Line Chart

Like the bar chart, the line chart is another of the most frequently used chart types. These charts connect individual numeric data points to visualize a sequence of values. As such, they are most commonly used when an element of time is present. In fact, the best use case for line charts involves displaying trends over a period of time (see Figure 5.5), when your data are ordered, or when interpolation makes sense.

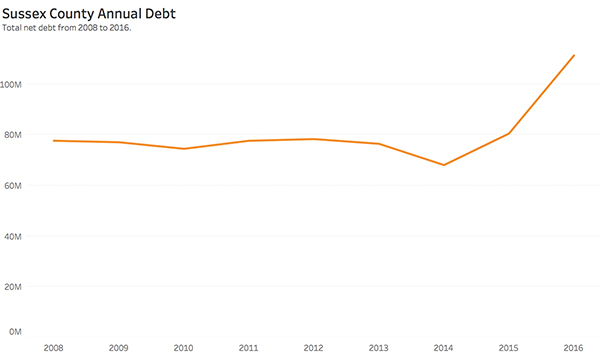

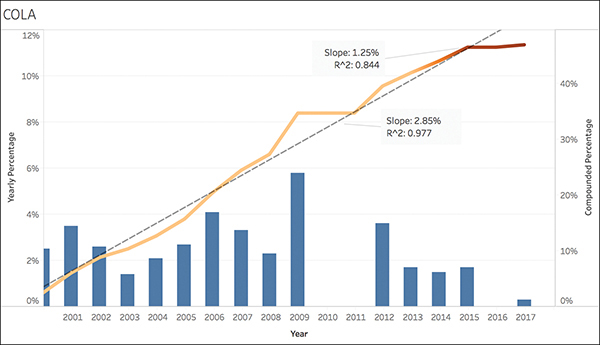

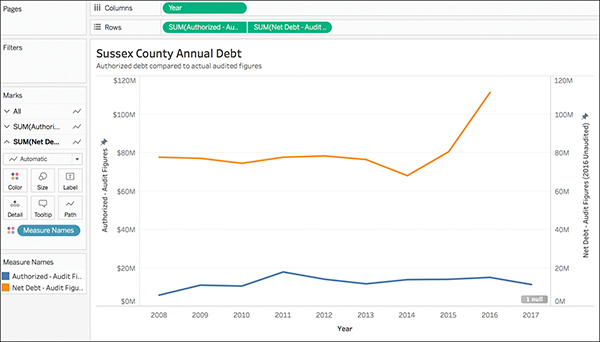

Figure 5.5 This line chart shows the audited annual net debt for Sussex County over a period of nearly ten years.

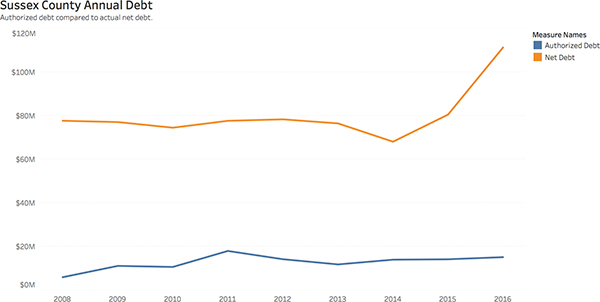

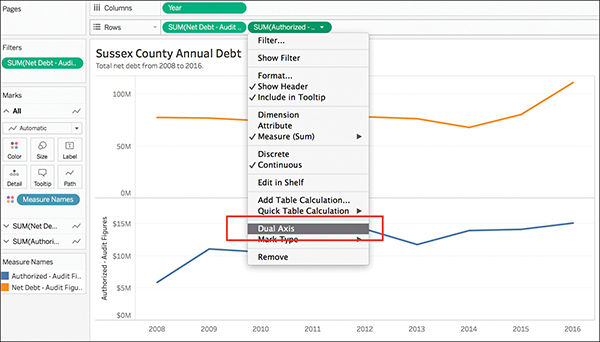

Dual-axis line charts can be created by bringing two measures to the rows shelf, and then right-clicking on the second measure and selecting Dual-axis from the drop-down menu (see Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6 Create a dual-axis line chart by combining two measures. This produces a line chart with multiple lines.

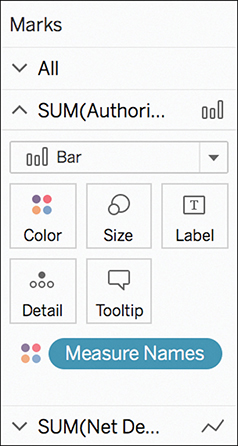

Additionally, when two or more lines are present, you can transform line charts by adding additional chart types to deepen insight. For example, a line chart can be combined with a bar chart (see Figure 5.7) to provide visual cues for further investigation. Or, the area under lines can be shaded into an area chart by filling the space under each respective line to extend the analysis and illuminate the relative contribution that a line contributes to the whole.

Figure 5.7 Adjust the Marks card to help you combine chart types. This work-in-progress line chart has been combined with a bar chart. It also includes annotations, trend lines, and a color gradient shade element on the line to enhance insight.

Tableau How-To: Line Chart

You create a line chart in Tableau by placing one or more measures on either the columns shelf or the rows shelf, and then plotting the measures against either a date or continuous dimension (see Figure 5.8). Additionally, the Automatic Marks card drop-down menu will select Line as the mark type. You can further expand line charts by including additional summary analytics, like forecasting. Be sure to synchronize or adjust axes to keep numbers in context.

Figure 5.8 Create a dual-axis line chart to show two pieces of data on the same chart.

The Pie and Donut Charts

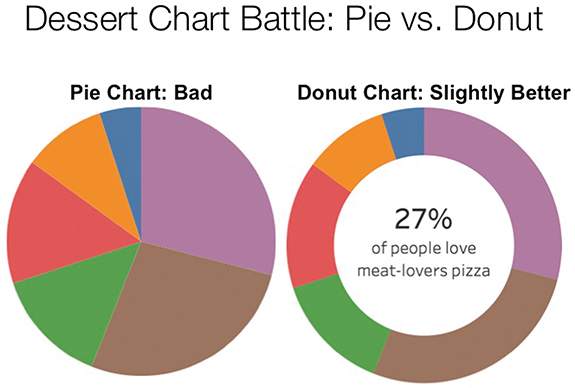

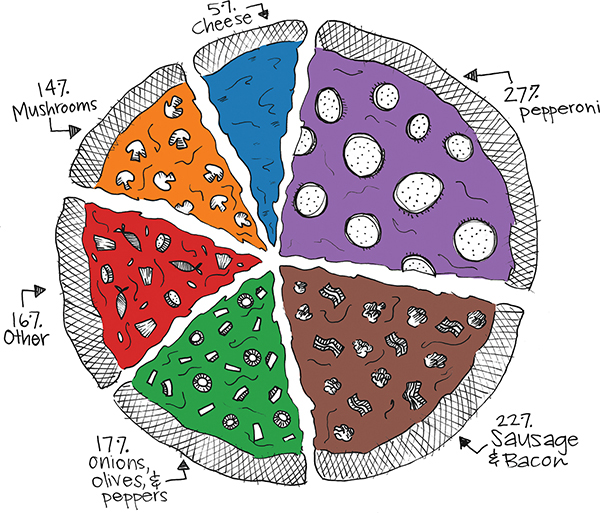

We all love to hate the pie chart and its cousin the donut chart. This hatred for “dessert charts” is prolific with a lot of opinions thrown in the mix, but a substantial amount of empirical research explores many good reasons not to use these charts. Among these, known problems exist with how we read and understand angles and the many distortion effects caused by too many slices (which apply to both pie and donut charts). Even so, these charts are still among the most misused and overused of chart types. Nevertheless, with a few tweaks there are ways that both of these notorious chart types can be used—with discretion—as viable options to visualize parts of a whole, or percentages (see Figure 5.9), particularly for use as storyteller, rather than analytical, visualizations.

In both charts the circle represents the 100% whole, and the size of each wedge (the largest of which should start on the upper right and move clockwise) represents a percentage. The trick to properly reading pie or donut charts is to not rely on the angle, but to look at area or arc length. To avoid a bad pie chart, focus on comparing only a few values (less than six is preferable, two if possible) and use distinct color separation for maximum readability. Donut charts can help clarify your data story by including a key takeaway in the center white space (see Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.9 A side-by-side comparison of an unlabeled pie chart and a donut chart displaying percentages of America’s favorite pizza toppings.

Tableau How-To: Pie and Donut Charts

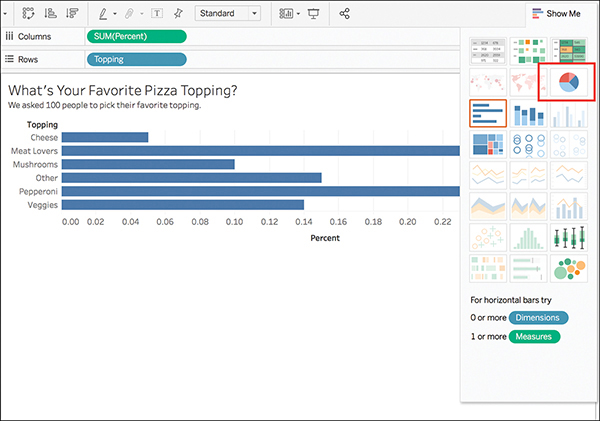

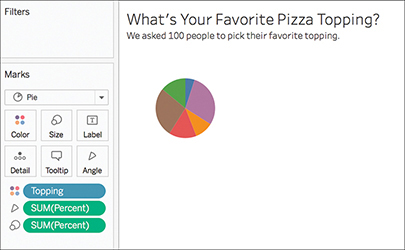

To begin either a pie or donut chart, you start by building a basic bar chart and then use the Show Me card to select the pie chart option (see Figure 5.10). You could also create a pie chart directly in the Marks card. This will produce a rather small pie chart.

tip

You can increase the size by holding down Ctrl+Shift (or holding down Command+Shift on a Mac) and pressing B several times.

Figure 5.10 Create a bar chart, and then select the pie chart from the Show Me card.

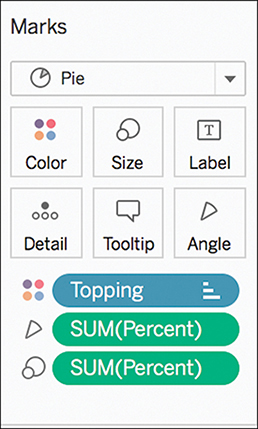

While there is not a one-click or Show Me option to change a pie chart into a donut chart, a few additional steps will transform your chart:

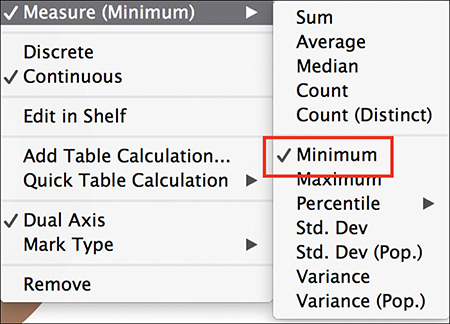

1. Beginning with a pie chart, drag your measure to the Rows shelf again. Right-click both instances and select Measure (Sum) > Minimum (see Figure 5.11).

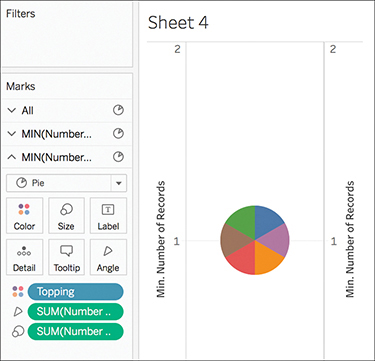

2. Right-click the second instance of Number of Records and select Dual Axis.

Figure 5.11 Transform a pie chart into a donut chart by creating a dual-axis chart.

3. Now to combine two pie charts into one, transforming the second into what will become the center of your donut: Move to your Marks card, click the second instance of your measure and click MIN(Number of Records) (2).

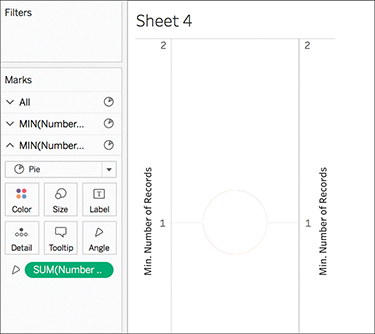

4. Remove any pills from the Color and Size marks.

5. Click Color and choose the same color as the background (in this example, white).

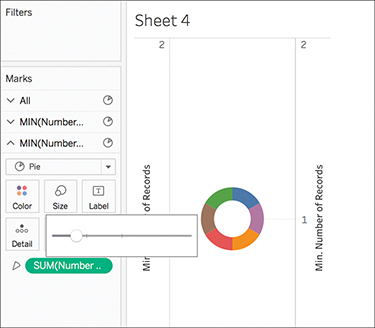

6. At this point, your pie chart will appear to disappear; however, select Size and drag the slider to the left to make the circle smaller. As the white circle decreases, the center of your donut “hollows” out (see Figure 5.12).

Figure 5.12 These visuals reflect the steps to transform your pie chart into a donut chart.

From this point, you can finalize your donut chart by removing headers, showing labels, and so on.

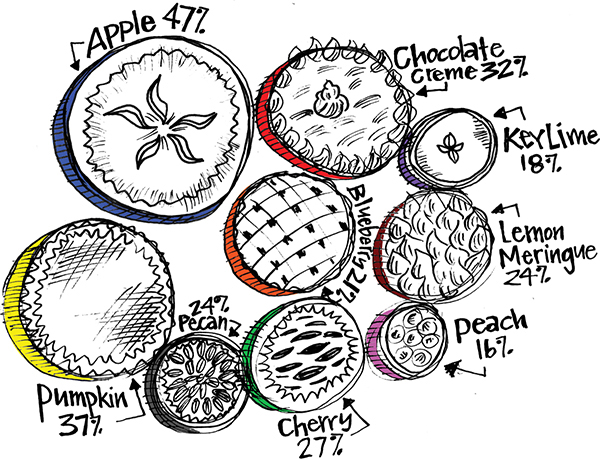

SKETCHING YOUR STORY

Sketching out ideas for your graphics can aid with the artistic process as you work to frame your story (see Figure 5.13). If you can create a vision of your story, you can use this as a guide to curate meaningful charts and graphs. Of course, Tableau doesn’t support sketching; however, these guides can be helpful as you work to curate your visual in Tableau to tell its best story.

Figure 5.13 Sketching out stories can facilitate the artistic process of visualization and help you see your end goal as you work to curate it in Tableau.

The Scatter Plot

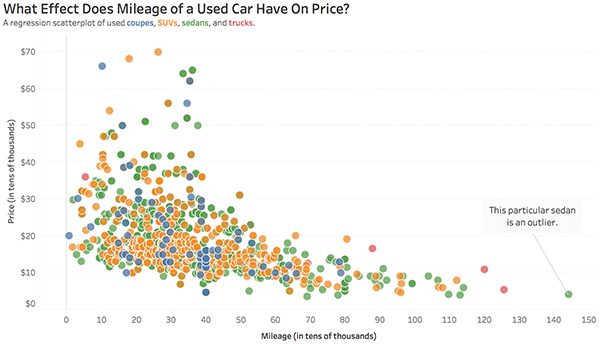

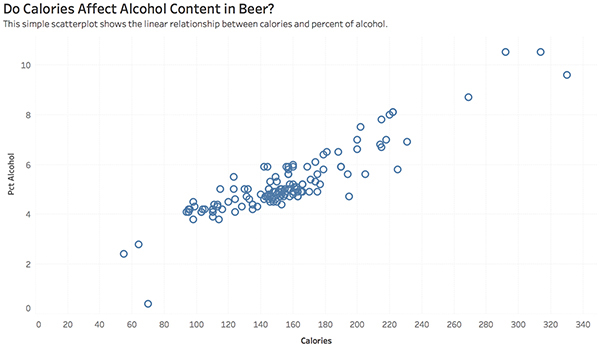

Scatter plots are an effective way to visualize numerical variables to compare measures and quickly identify patterns, trends, concentrations (clusters), and outliers. These charts can give viewers a sense of where to focus discovery efforts further and are best used to investigate relationships between variables. Scatter plots are particularly useful when exploring statistical relationships such as linear regression. Figure 5.14 illustrates an example of the scatter plot.

Figure 5.14 Scatter plot example.

Tableau How-To: Scatter Plots

You can create a scatter plot in Tableau in two ways: as a simple scatter plot or a matrix scatter plot.

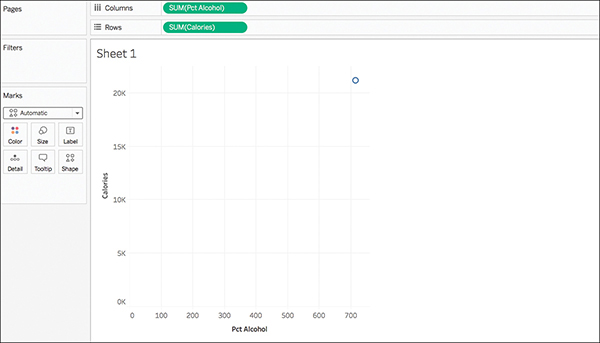

You create simple scatter plots by dragging a measure to the Columns shelf and a measure to the Rows shelf. When you plot one number against another, the result is a Cartesian chart—a one-mark scatter plot with a single x and y coordinate (see Figure 5.15).

Figure 5.15 Simple scatter plots begin with aggregated measures, showing only one mark.

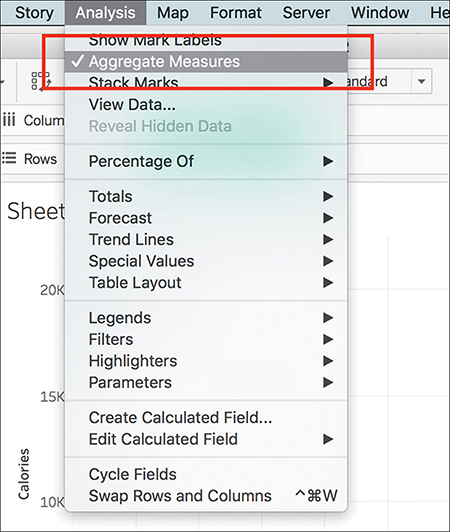

To view all of your measures, deselect the Aggregate Measures option from the Analysis menu (see Figure 5.16).

Figure 5.16 Deselect Aggregate Measures to view all of your data points on a scatter plot.

Doing so generates a simple scatter plot, as shown in Figure 5.17.

Figure 5.17 A simple scatter plot.

You can add depth and visual richness to a scatterplot by:

![]() Bringing over dimensions and using them to add color or additional shapes onto the scatter plot.

Bringing over dimensions and using them to add color or additional shapes onto the scatter plot.

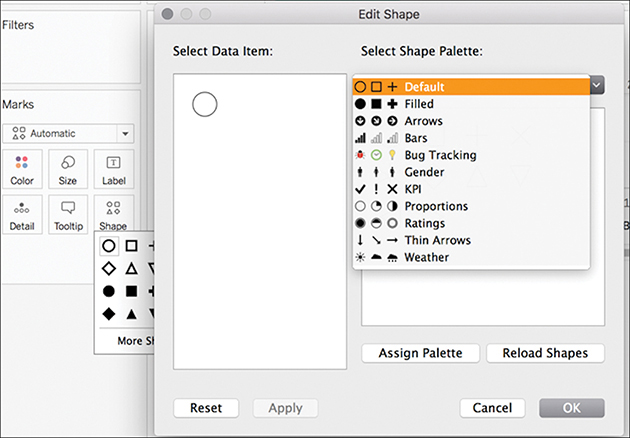

![]() Changing the shape of the data via the Marks card to provide additional relevance and visual cues. You can choose these shapes from a set of sample default shapes as well as a selection of shape palettes included in Tableau (see Figure 5.18).

Changing the shape of the data via the Marks card to provide additional relevance and visual cues. You can choose these shapes from a set of sample default shapes as well as a selection of shape palettes included in Tableau (see Figure 5.18).

Figure 5.18 Choose shapes from the Marks card to add depth to your scatter plot.

![]() Incorporating filters can reduce noise and help limit investigation to the factors that matter most to your analysis.

Incorporating filters can reduce noise and help limit investigation to the factors that matter most to your analysis.

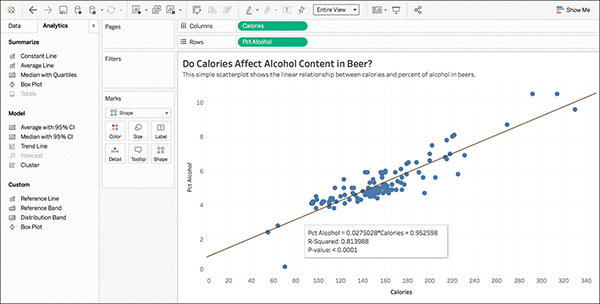

![]() Scatter plots are excellent candidates to include statistical information to review trends and other analytics. Via Tableau’s Analytics pane, you can add a variety of analytic models to highlight the statistics in your data. Hover the cursor over the trend lines to display statistical information used to create the line(s), as shown in Figure 5.19.

Scatter plots are excellent candidates to include statistical information to review trends and other analytics. Via Tableau’s Analytics pane, you can add a variety of analytic models to highlight the statistics in your data. Hover the cursor over the trend lines to display statistical information used to create the line(s), as shown in Figure 5.19.

Figure 5.19 A scatter plot with a trend line and summary statistics.

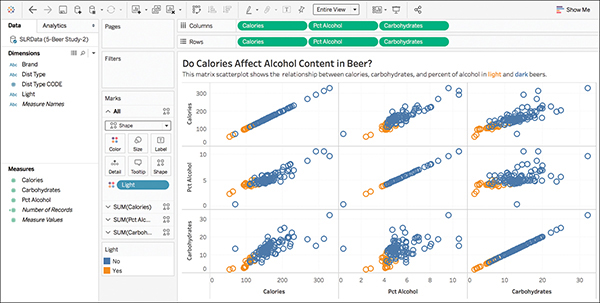

If these shelves contain both dimensions and measures, Tableau will create a Matrix of Scatter Plots and place the measures as the innermost fields, which means that measures are always to the right of any dimensions that you have also placed on these shelves. The word innermost in this case refers to the table structure (see Figure 5.20).

Figure 5.20 A matrix scatter plot.

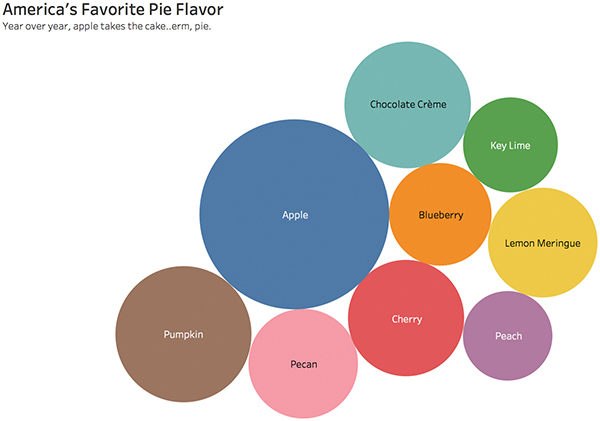

The Packed Bubble Chart

The bubble chart is a variation of the scatter plot that replaces data points with a cluster of circles (or bubbles), a technique that further emphasizes data that would be rendered on a pie chart, scatter plot, or map. This method shows relational values without regard to axes and is used to display three dimensions of data: two through the bubble’s location and another through size.

These charts allow for the comparison of entities in terms of their relative positions with respect to each numeric axis and size. The sizes of the bubbles provide details about the data, and colors can be used as an additional encoding cue to answer many questions about the data at once (see Figure 5.21). As a technique for adding richness to bubble charts, consider overlaying them on a map to put geographic data quickly in context.

Figure 5.21 A packed bubble chart displays data in a cluster of circles, using size and color to encode the bubbles with meaning.

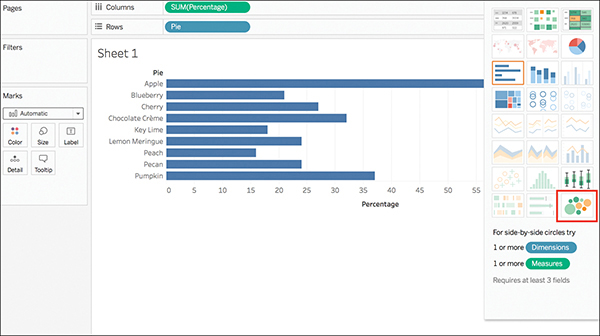

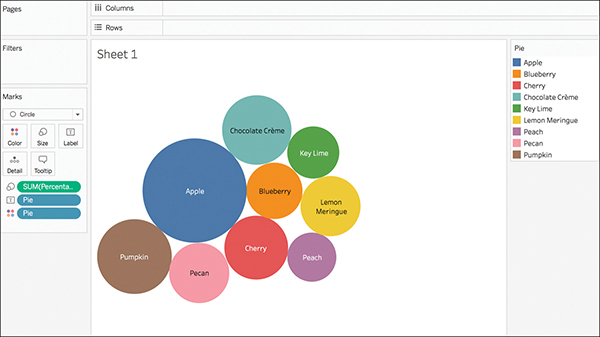

Tableau How-To: Packed Bubble Charts

To create a basic packed bubble chart, drag a dimension to the Columns shelf and a measure to the Rows shelf. Tableau will aggregate the measure as a sum and create a vertical axis to display a bar chart. This is the default functionality when you select one measure and dimension in this manner. Next, use the Show Me card to select the Packed Bubble chart from the list of options (see Figure 5.22).

In this example, the size of the bubble represents the number of survey responses whereas the color of the bubble represents the flavor or pie chosen. The circle is also labeled with the flavor.

Figure 5.22 Building a packed bubble chart in Tableau begins with building a bar chart and changing the chart type.

Like most chart types, there are ways to add more insight into a packed bubble chart or embellish the chart with storytelling techniques. For example, use different dimensions to encode color, or adjust labels to add additional information. (Chapter 9 covers formatting Mark labels.)

Shapes, especially circles, also provide an interesting opportunity to move beyond data visualization tools to bring your story to life in creative ways (assuming, of course, this works for your audience and your story). In Figure 5.23, images of the pie flavors overlay the bubbles, presenting the same data in a more visual way. Because we are interested in the story here more than the analytics, this works.

Figure 5.23 A more artistic storytelling approach to this same data story.

note

You might recognize this image from Wake’s Pis: A Kid’s Guide to Delicious Data Stories. For more of Wake’s work, check out www.wakespis.com.

The Treemap

One of the two more advanced visualizations covered in this chapter, the treemap uses a series of rectangles of various sizes to show relative proportions (see Figure 5.24). It works especially well if the data being visualized has a hierarchical structure (with parent nodes, children, and so on) or when analyzing a parts-to-whole relationship. As its name suggests, a treemap divides and subdivides based on parts of a whole by breaking down into smaller rectangles nested within a larger rectangle, often of a different color or different color gradient, to emphasize its relationship to the larger whole.

The treemap also provides a much more efficient way to see this relationship when working with large amounts of data by making efficient use of space. It is ideal for legibly showing hundreds (or perhaps even thousands) of items simultaneously within a single visualization.

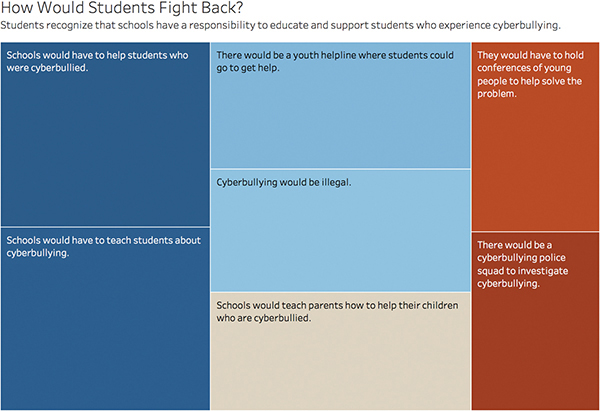

Figure 5.24 This treemap shows the rate of student survey responses on how they perceive schools should fight back against cyberbullying. The sizes and shapes of the rectangles give further detail on their relationship within the hierarchy of total answers.

Tableau How-To: Treemaps

Use dimensions to define the structure of a treemap, and measures to define the size (or color) of the rectangles.

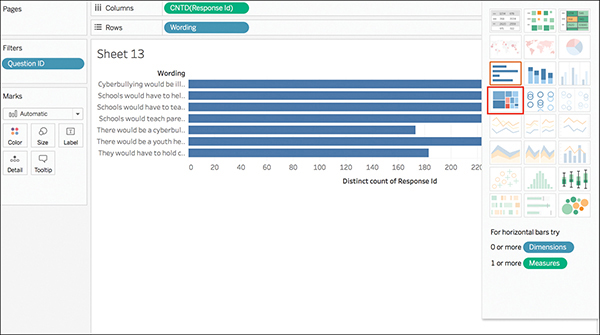

Again, drag a dimension to the Columns shelf and a measure to the Rows shelf. Tableau will aggregate the measure as a sum and create a vertical axis to display a bar chart (see Figure 5.25). From here, use the Show Me card to select a treemap from the list of available chart types.

Figure 5.25 Building a treemap in Tableau begins with building a bar chart and changing the chart type.

In this example, we are using survey data to create the treemap and looking at how many respondents selected each of the options presented. Both the size of the rectangles and their color are determined by the value of Response ID—the greater the sum of unique responses for each category, the darker and larger its box (this is further clarified by the color legend at right).

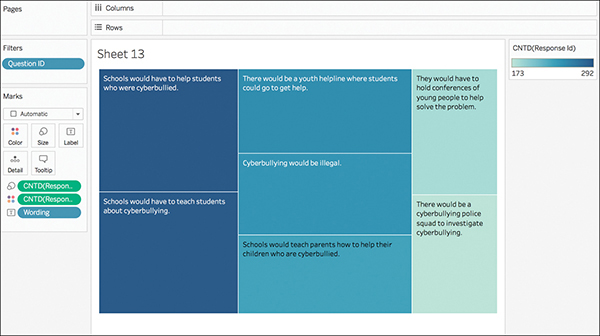

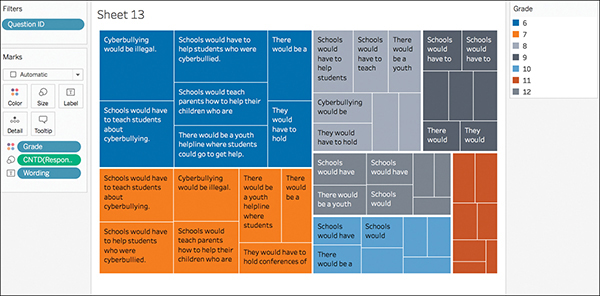

Size and Color are crucial elements in treemaps. You can modify a treemap by adjusting how color is utilized. For example, in Figure 5.26 I have removed count of Response ID from Color and replaced it with Grade. Now, Grade determines the color of the rectangles and the count of Responses still determines the size of rectangles, allowing us to see top responses per grade.

Figure 5.26 Modify elements on the Marks card to adjust the elements of color and shape in a treemap.

The Heat Map

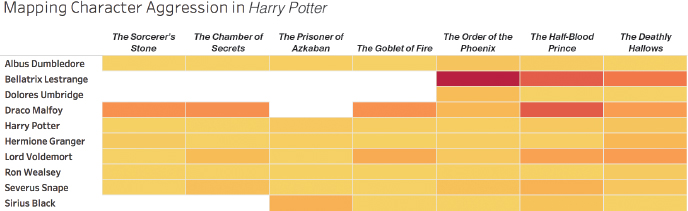

A heat map graph is a great way to compare categorical data using color (see Figure 5.27). Similar to the tree map, a heat map represents the values by a variable in a hierarchy. They are similar in concept to the type of complex visual data representation that you might see used on your local weather forecast by the meteorologist to illustrate rainfall patterns across a region. However, they are not limited to use with maps.

Figure 5.27 A heat map of frequency of aggressive acts committed in Harry Potter.

Tip for navigating this type of visualization include:

![]() Adding a size variation for squares to show the concentration of intersecting factors while adding a third element.

Adding a size variation for squares to show the concentration of intersecting factors while adding a third element.

![]() Using a shape other than a square to convey meaning in a more impactful way.

Using a shape other than a square to convey meaning in a more impactful way.

Tableau How-To: Heat Maps

Building a heat map in Tableau takes a few more clicks than with some of the other charts discussed.

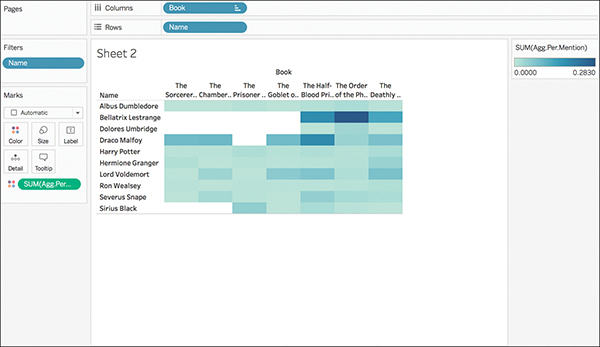

To begin, place one (or more) dimensions onto the Columns shelf and one (or more) dimensions on the Rows shelf. Select Square as the mark type and place a measure on the Color shelf (see Figure 5.28).

Figure 5.28 Building a heat map.

note

In Figure 5.28 I have already manually sorted the order of books (you can see the sort icon on the Book pill) and filtered the number of characters down (you can see the Name pill in on the Filters shelf).

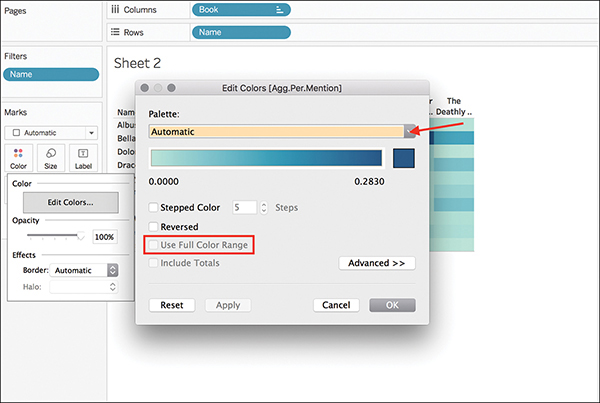

There are a few more steps to curate this heat map. The preceding example uses an automatic blue gradient color palette. There might be more appropriate color palettes depending on the data you are looking at. For example, Figure 5.27 shows the use of a red-gold gradient scheme to progressively darken the cell color in line with characters’ aggressive action counts. You can enter the Colors box in the Marks card, and then select Edit Colors to open the Edit Colors dialog box (see Figure 5.29). From here you can select another color palette from the drop-down menu. This can be either a gradient palette or a diverging palette.

Figure 5.29 Use the Edit Colors dialog box to select an appropriate color scheme for a heat map.

![]() If you select the Use Full Color Range check box for a diverging option, Tableau will assign the starting number a full intensity and the ending number a full intensity.

If you select the Use Full Color Range check box for a diverging option, Tableau will assign the starting number a full intensity and the ending number a full intensity.

![]() If you don’t select Use Full Color Range, Tableau will automatically assign the color intensity as if the range were from –100 to 100, maximizing the color contrast as much as possible.

If you don’t select Use Full Color Range, Tableau will automatically assign the color intensity as if the range were from –100 to 100, maximizing the color contrast as much as possible.

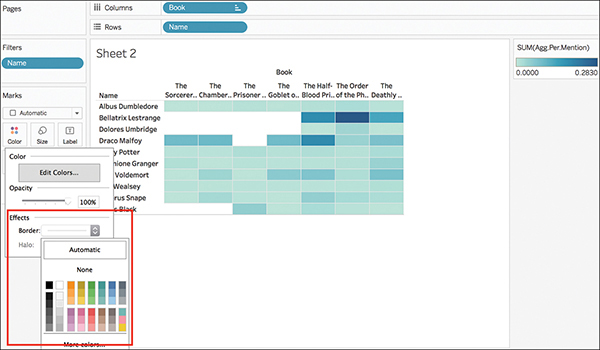

Additional visual cues, like lines, are also important contributors to curating heat maps. You can add borders to each colored cell in the view by revisiting the Color Editor box and selecting an appropriate border color from the Effects portion of the border dialog (see Figure 5.30).

Figure 5.30 Adding borders to colored cells helps to distinguish individual cells in the view.

RECOMMENDED READING

Check out the Tableau white paper: Which Chart or Graph for additional information: https://www.tableau.com/learn/whitepapers/which-chart-or-graph-is-right-for-you.

Maps

If you want to analyze or present your data geographically, Tableau has several native mapping capabilities. Maps can be used to display geographic data or as a way to communicate answers to spatial questions, like “Which states offer the most analytics education programs” or “Which regions in the U.S. have the most incidents of Lyme disease?”

While maps can be a great way to tell a story about your data, remember that they are a type of visualization and do have an appropriate use case. Depending on the question you are trying to answer or the insight you are trying to communicate, another chart type might be a more appropriate fit. Before you begin building a map, be sure to take a careful look at your data, your analysis, and your story. Maps, as Tableau explains, should answer questions that have both “appropriate data representation and attractive data representation. As a storytelling device, maps can be particularly tricky in their tendency to mislead or inadvertently cause people to misinterpret the data, or to dictate a not-quite-true story.

Tableau can be customized to create several types of maps; however, this section covers the two most common: proportional symbol maps and choropleth (or filled) maps.

note

Tableau capabilities include many advanced map types and customization functions that are not covered in this text. Tutorials and use case information for more advanced maps, such as point distribution maps, which help you look for visual clusters of data; flow (or path) maps that connect paths to see where something went (for example, storms or product sales) over time; and spider (or origin-destination) maps that show how an origin location and one or more destination locations interact can be found online. For more info, visit Tableau Help > Maps.

WHAT GEODATA DOES TABLEAU SUPPORT?

Tableau recognizes a set of geographic roles defined by a geocoding database that uses latitude and longitude coordinates. By default, Tableau supports geodata including:

![]() Worldwide airport codes

Worldwide airport codes

![]() Cities

Cities

![]() Countries/regions/territories

Countries/regions/territories

![]() States/provinces

States/provinces

![]() Some postcodes and second-level administrative districts (county-equivalents).

Some postcodes and second-level administrative districts (county-equivalents).

![]() U.S. area codes

U.S. area codes

![]() Core-Based Statistical Areas (CBSA)

Core-Based Statistical Areas (CBSA)

![]() Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA)

Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA)

![]() Congressional districts

Congressional districts

![]() Zip codes

Zip codes

Additionally, Tableau organizes geographic roles within a hierarchical order. The order is City > County > Zip Code > CBSA/MSA > Area Code > State > Country/Region. When you place multiple geographic fields on Detail on the Marks card, Tableau plots the data points in the field with the highest geographic role on this list.

Connecting to Geographic Data

Although you are already familiar with connecting to data in Tableau at this point, geographic data comes in many shapes and formats so it is useful to walk through this step of the process again within the context of mapping to discuss where geodata nuances might affect the process as you prepare to work with geographic data.

note

Newer visions of Tableau Desktop can connect directly to spatial files (like shapefiles or geoJSON files); however, following the precedent established in this book these examples demonstrate connecting to data in Excel.

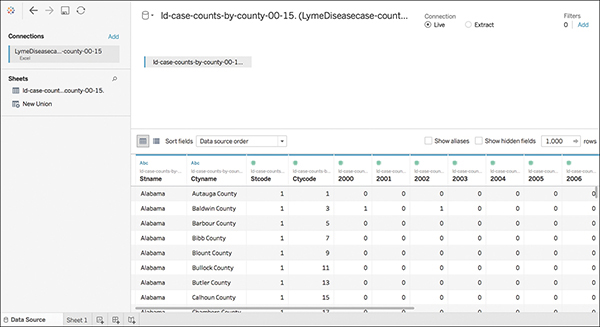

In this exercise, I connect to a dataset of incidents of Lyme disease. This dataset provides a count of Lyme disease cases by state and county from 2000 to 2015 (see Figure 5.31).

note

This Lyme disease dataset is publically available from the Center for Disease Control. You can download the data at https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/index.html.

Figure 5.31 This dataset, available from the CDC, contains the number of incidents of Lyme disease over a 15-year period.

Assigning Geographic Roles

After connecting to your data source, you might need to take a few more steps before your geographic data is fully prepared for analysis in Tableau. These steps will not always be necessary to create a map, and might differ depending on your data and the type of map you intend to create. Regardless, all geographic fields should have a data type of string, a data role of dimension, and be assigned the appropriate geographic roles. (The exception is latitude/longitude, which should have a data type of number (decimal), a data role of measure, and be assigned the Latitude and Longitude geographic roles.)

Let’s practice adjusting data types for geographic data in the CDC dataset.

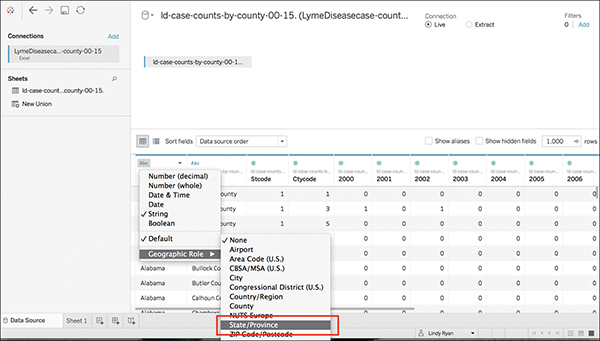

This simple dataset has two geographic fields: State and County. Tableau has correctly identified these data types as string; however, clicking on the field and looking at geographic roles reveals that none have been assigned (see Figure 5.32). You might need to assign or edit the geographic role assigned by Tableau. In this example, two things must be done:

![]() Adjust the State field to the Geographic Role of State

Adjust the State field to the Geographic Role of State

![]() Adjust the County field to the Geographic Role of County

Adjust the County field to the Geographic Role of County

Figure 5.32 Geographic roles can be assigned, or changed directly from the data source screen. They can also be changed in a worksheet.

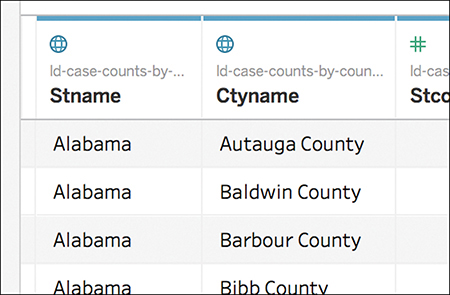

With this adjustment you will see the data type icon change to a globe, representing that the field now has a geographic role assigned (see Figure 5.33). Further, the icon designated in blue indicates that Tableau has assigned this field as a dimension. This is correct.

Figure 5.33 The globe icon reflects the geodata field assignment in Tableau.

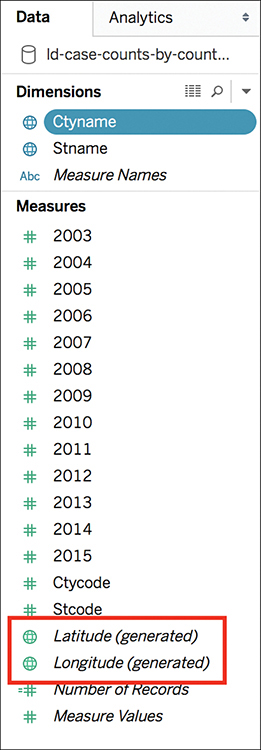

When you assign the correct geographic role to a field in Tableau, the software will also assign a latitude and longitude to each location. It does this by finding a match that is already built into the geocoding database that is installed with Tableau Desktop. These latitude and longitude fields will display on the Data pane as measures, and are how Tableau knows where to plot your data locations as you begin building a map (see Figure 5.34). (Note: In some advanced maps, you might elect to have your latitude and longitude coordinates as dimensions. These should be considered special uses and are not covered here.)

Figure 5.34 When Tableau recognizes geodata, latitude and longitude fields are automatically displayed as measures on the Data pane.

Creating Geographic Hierarchies

In the Tableau worksheet space, if you have more than one level of geographic data in your dataset you can create geographic hierarchies. While these are not critical to creating a map, geographic hierarchies will allow you to quickly drill into the levels of detail your data contains. Because this dataset has both State and County, you can create a hierarchy using these two fields. As State is the larger field in the hierarchy, let’s begin there.

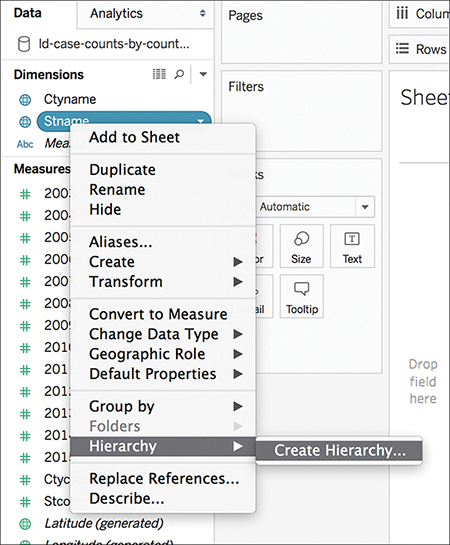

To create a geographic hierarchy, right-click the field that represents the highest level of geographic data in the Data pane. Select Hierarchy > Create Hierarchy (see Figure 5.35).

Figure 5.35 Creating hierarchies enables you to drill down to geographic levels of interest.

A dialog box appears that prompts you to name the hierarchy schema, such as Location Data. Enter a name and click OK.

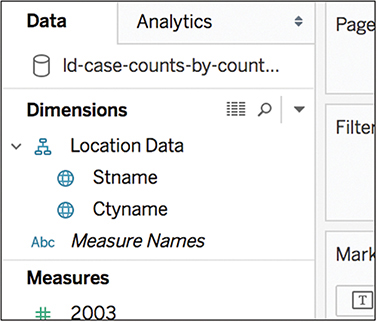

A new field now appears in the Dimensions pane with the name of the hierarchy just created. The highest level geographic data used to create the hierarchy, in this example, state, appears as the first rung in the hierarchy. To add additional fields, simply drag and drop into the hierarchy, placing them in correct order. Repeat as necessary until all geographic fields are included in the hierarchy. Figure 5.36 shows county has been added into the hierarchy below state.

Figure 5.36 Example of geographic hierarchy.

Proportional Symbol Maps

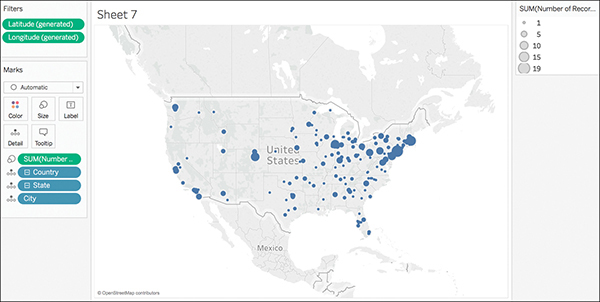

Proportional symbol maps are useful ways to show quantitative values for individual locations. They can show one or two quantitative values per location, and can be encoded with visual cues like size and color. The proportional symbol map displayed in Figure 5.37 shows the number and level of analytic academic programs across the U.S. plotted using the open dataset used in Chapter 1.

note

You can download this public, and constantly updating, dataset from https://github.com/ryanswanstrom/awesome-datascience-colleges.

Figure 5.37 This symbol map shows the number and type of academic analytics programs available in the U.S. with legends.

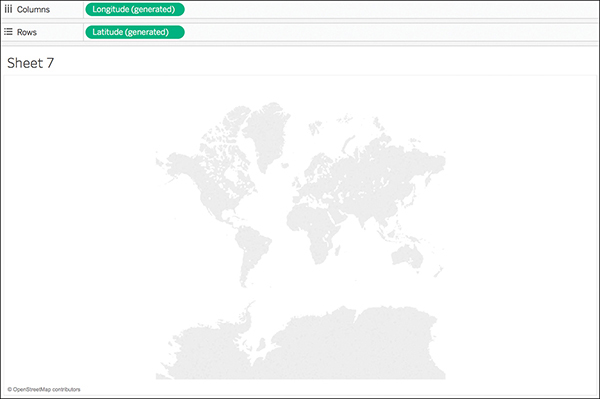

The first step to building a map is to give Tableau geographical coordinates to work with to lay the foundation of the map. Double-click the Latitude and Longitude generated fields under Measures. Latitude is added to the Rows shelf, and Longitude to the Columns shelf. Initially, a blank map view is created (see Figure 5.38).

Figure 5.38 The first step in building a map visualization is to display the Latitude and Longitude coordinates to generate a blank map.

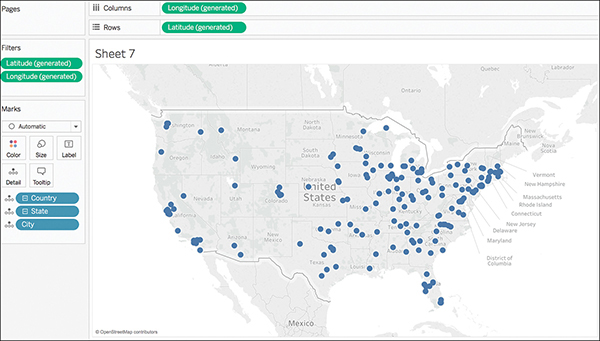

Next, drag out the dimension that represents the location you want to plot your map by and drop it on the Details card. From the hierarchy group in this dataset, I’ve brought over City to look at programs offered at specific universities. A lower level of detail is added to the view.

note

In this dataset, several international locations now show as Unknown. I’ve filtered these out to focus only on U.S.–based programs. I have further limited the view to the contiguous 48 states (see Figure 5.39).

Figure 5.39 Add dimensions to the Detail Marks card to begin populating the data displayed on the map.

With a level of detail now on the map, the next step is to bring over the Measure to encode size. In this example I am interested in seeing the number of programs per location, so I can simply bring the Number of Records Dimension to the Size Marks card. With the size of the bubbles representing the number of programs at each location, we can visualize the range of values more clearly (see Figure 5.40).

Figure 5.40 Adding detail to the Size Marks card can enhance the ways symbols appear on the map and encode additional data.

This is the basis of a proportional symbol map. The larger data points represent the locations with the larger total number of programs, and the smaller data points represent the locations with few analytics program options.

Although this shows a good picture of program availability, there is more to do to encode this map with more data and tell a better story. To get a better of idea of which programs are offered at various locations, by degree level, we can bring over Degree dimension to the Color Marks card. (Note: Although this dataset includes everything from Associate Degrees through Doctoral Degrees, I have excluded Associates.)

The proportional symbol map is now complete (see Figure 5.41).

Figure 5.41 Together, color and size can add significant layers of detail to a map.

At this point, your map should look similar to the one displayed previously in Figure 5.37. However, a few more tweaks can help to make the data in your map shine. Try the following:

![]() Sort your categories in an order that makes logical sense. This map has degrees sorted by highest level (Doctoral) to lowest (Bachelor).

Sort your categories in an order that makes logical sense. This map has degrees sorted by highest level (Doctoral) to lowest (Bachelor).

![]() Color as usual; I’ve used the colorblind palette to manually select appropriate colors for each degree in the hierarchy, on a makeshift blue-orange color scale. Additionally, adjust the opacity so that no points are lost behind colors of larger value/darker color. You can also add borders around circles to separate marks.

Color as usual; I’ve used the colorblind palette to manually select appropriate colors for each degree in the hierarchy, on a makeshift blue-orange color scale. Additionally, adjust the opacity so that no points are lost behind colors of larger value/darker color. You can also add borders around circles to separate marks.

Choropleth Map

A choropleth (or filled) map is a great tool for showing ratio or aggregated data. These maps use shading and coloring within geographic areas to encode value to a quantity in those areas. A dataset for choropleth maps should include both quantitative and qualitative values, along with location information recognizable by Tableau.

This example returns to the CDC Lyme disease dataset.

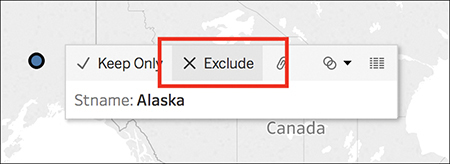

To begin building the map, double-click State. Longitude and Latitude are moved to the Columns and Rows shelves, and a map view with one data point for each state in the data source appears. To look at only the contiguous 48 states, select the Alaska and Hawaii data points, and click Exclude to remove them from view (see Figure 5.42).

Figure 5.42 You can exclude data by hovering over the data point and clicking Exclude.

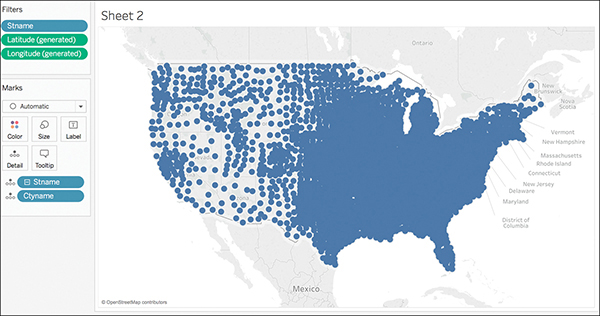

Now, let’s drill down to a better level of detail. On the Marks card, click the plus icon to drill town to County. This results in a data point for every county within the data source (see Figure 5.43). (If necessary, you can filter any nulls at this point.)

Figure 5.43 This is a nice example of why a choropleth can be a better alternative than a symbol map. There is simply too much data to show in individual points, but all is necessary for analysis.

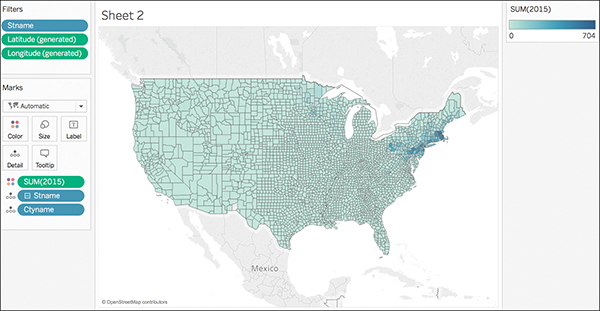

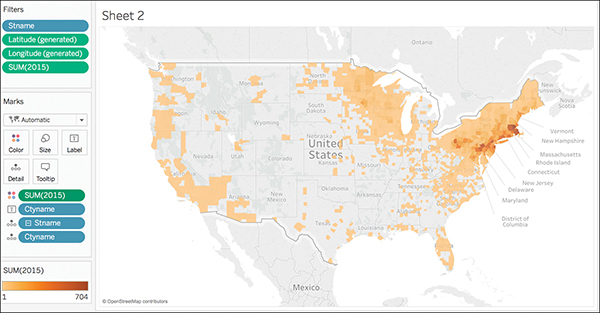

From here, to transform the symbol map to a filled map, bring a measure to Color on the Marks card. This example uses 2015, the most recent date for the data. The map changes to a filled map mark type and the polygons are colored blue by default (see Figure 5.44). Notice that the default aggregation type for the 2015 measure is SUM by default; however, this might not be the best fit depending on your data. Take a moment to verify that the field should be aggregated as a sum (because this is a count of incidents reported, a sum is appropriate).

Figure 5.44 Choropleth maps use sequential coloring to embed values in map regions.

Now, let’s improve this visualization to tell a better story about the data and complete this choropleth map.

1. On the Marks card, click Color and Edit Colors. Because these are disease incidents, choose a more alerting color, perhaps Orange.

2. Click again on the Marks card and under Effects, remove the Border option by clicking None.

3. Edit the color filter so that it applies colors only to counties that have had at least one incident of Lyme disease. This is an important step in ensuring that the map tells an accurate story, while drawing attention to areas in which Lyme disease is prevalent.

The choropleth map displaying 2015 incidents of Lyme disease within the contiguous states is complete, and paints a grim picture for New England (see Figure 5.45).

Figure 5.45 Color choice on a choropleth map is important and should follow the color practices described earlier in this text.

note

The level of detail specified in the map as well as the color distribution specified for the polygons affects how the data is represented, and how people will interpret the data. In some cases, stepped color might be more appropriate.

note

Again, as discussed in the previous chapter, context is everything. With maps, keeping population sizes in context is especially important. You might need to “normalize” your data with a calculated field to ensure you are looking at populations in context of their geographic regions.

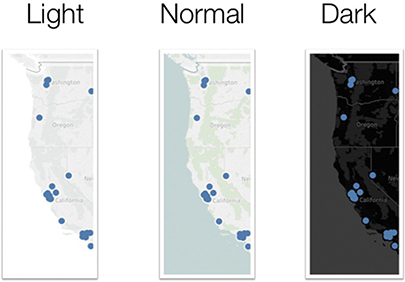

MAP LAYERS

Of the many customization features for maps in Tableau, one of the most interesting is choosing between the built-in map background styles to adjust the background of your map. The three background options offered in Tableau are Normal, Light (the default), or Dark. Figure 5.46 shows each background option.

Figure 5.46 Three standard map backgrounds available in Tableau.

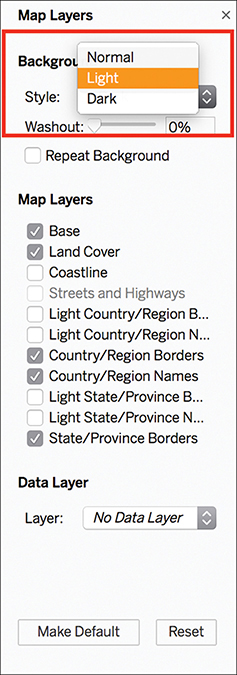

To select a Tableau map background style choose Map>Map Layers and adjust the Style in the Map Layers box (see Figure 5.47).

Figure 5.47 You can adjust map backgrounds and other formatting stylistics in the Map Layers pane.

You can also experiment with importing your own background map, adding a static background map image, and adding or subtracting map layers by data layers. Learn more at http://onlinehelp.tableau.com/current/pro/desktop/en-us/maps_options.html.

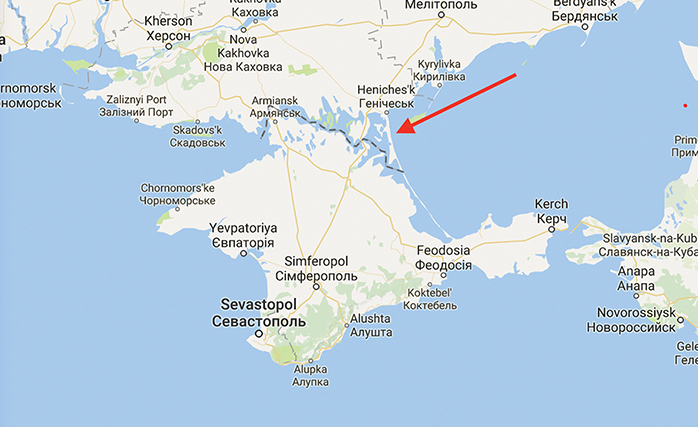

KEEPING MAPS NEUTRAL

Visualizations are not neutral and maps, like any storytelling device, can be used to mislead audiences if not designed correctly and honestly—and customized for the audience. Google Maps does this with lines and how it adjusts views for disputed territories. For example, Russian users see Crimea marked off with a solid line indicated that the area belongs to Russia, but for Ukrainian users the solid line is replaced with a dashed stroke indicating that the peninsula belongs to the Ukraine. Everyone else, like us in the U.S., see a hybrid line that reflects Crimea’s disputed status (see Figure 5.48).

Figure 5.48 This Google Maps version of the Crimea border is intended for a U.S.–based audience and shows a hybrid line that reflects the border’s disputed status.

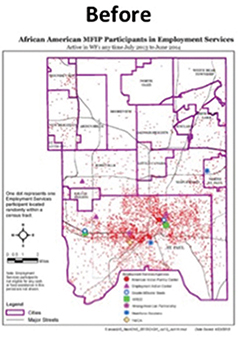

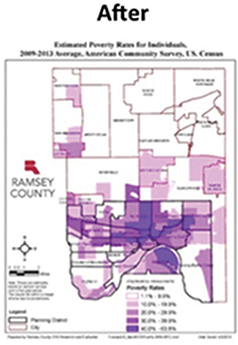

Additionally, the manner in which we use shapes and colors to encode data that represents humans can be tricky on a map. One Minnesota poverty map recently changed from representing humans as red dots—which results in a map full of red swarm—to a gradient purple to look less aggressive (see Figure 5.49).

Figure 5.49 This unfortunate design choice to represent population was later adjusted to a more neutral, and less offensive, approach.

These examples, and many more, speak to the importance of paying special attention to how our assumptions, intuitions, and biases—or even the things we might not consider—affect how we build visualizations to tell stories about people and places. Check out this article for more: https://source.opennews.org/articles/when-designer-shows-design/.

Summary

This chapter explored how to create basic charts and maps displayed on the Show Me card in Tableau. The following chapter presents a pragmatic look at how to curate meaningful visualizations that take advantage of the visual processing horsepower of the human brain.