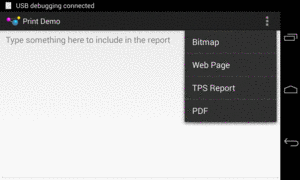

Figure 844: Print Demo App, Showing Overflow

Mobile devices are continuing to close the gap on capabilities that had formerly been the sole province of desktop systems or servers. After all, if the vision is that people should be able to use phones and tablets instead of desktops and notebooks, phones and tablets need to do whatever it is that those people need to have done.

One such capability is the ability to print to networked printers. While various third-party printing options had been available for some time, it is only starting with the Android 4.4 release that the OS and framework itself has support for printing. Hence, at this time, a significant majority of Android devices will be natively capable of printing, and so users will be more likely to expect that your app supports such printing.

As it turns out, the print engine in Android is centered upon the PDF document format, and Android supports converting HTML into PDF, albeit on a somewhat limited basis.

The API seems simple and clean. It actually is simple and clean… so long as you are printing very simple contents (bitmaps or HTML). Once you get into anything more complicated than that, the threading alone starts to make things rather messy.

This chapter describes how to use the Android 4.4 print system, including how to print HTML and PDF files. It will also cover how to generate HTML and PDF files, whether for printing or for other purposes (e.g., reports to be emailed or uploaded somewhere).

Understanding this chapter requires that you have read the core chapters

of this book. Also, you should read

the chapter on advanced uses of WebView.

Writing programs that print on desktop operating systems historically has been tedious. The fine-grained control that is needed for high-quality output makes the APIs complicated, and these tend to be only partially masked by high-level wrappers to simplify common scenarios.

Android’s print system is no different.

Starting with Android 4.4, you can request access to a PrintManager system

service (via getSystemService(), called on any Context). It offers a

print() method that lets you describe what should be printed, in the form of

a PrintAttributes (e.g., what size paper are you looking for?) and a

PrintDocumentAdapter. The latter is responsible for working with Android

to actually create the content to be printed.

print() returns a PrintJob, which you can use to examine the status of

the print request. PrintManager also offers a getPrintJobs() method that

returns all of your outstanding print requests. Note that you cannot access

print jobs from other applications.

Hence, the real complexity of printing lies in the PrintDocumentAdapter

implementation. This class is responsible for generating a PDF that represents

the content to be printed. This leads to four basic ways of working with

a PrintDocumentAdapter:

WebView for printing HTML contentCanvas-based PDF generation class, called

PrintedPdfDocument

printBitmap() on

PrintHelper

The

Printing/PrintManager

sample project demonstrates all but the Canvas option.

The UI is just a large EditText, designed for you to type in a message.

The action bar overflow contains four options:

EditText

Figure 844: Print Demo App, Showing Overflow

Google helpfully supplies a PrintHelper class in the Android Support

package that makes it trivially easy to print a bitmap. Just call printBitmap()

on the PrintHelper, after some minor configuration, and it takes over from

there.

In onOptionsItemSelected() of the sample app’s MainActivity, when

the user chooses the “Bitmap” item, we call

startActivityForResult() on an ACTION_GET_CONTENT Intent, to allow

the user to pick an image from the device or emulator:

case R.id.bitmap:

Intent i=

new Intent(Intent.ACTION_GET_CONTENT)

.addCategory(Intent.CATEGORY_OPENABLE)

.setType("image/*");

startActivityForResult(i, IMAGE_REQUEST_ID);

This, in turn, will trigger a call to onActivityResult(), once the user has

(presumably) chosen an image:

@Override

protected void onActivityResult(int requestCode, int resultCode,

Intent data) {

if (requestCode == IMAGE_REQUEST_ID

&& resultCode == Activity.RESULT_OK) {

try {

PrintHelper help=new PrintHelper(this);

help.setScaleMode(PrintHelper.SCALE_MODE_FIT);

help.printBitmap("Photo!", data.getData());

}

catch (FileNotFoundException e) {

Log.e(getClass().getSimpleName(), "Exception printing bitmap",

e);

}

}

}

If the user did indeed choose an image, we create an instance of PrintHelper,

call setScaleMode() to tell it fit the image to the page, and then call

printBitmap() to print the image.

setScaleMode() takes one of two values:

SCALE_MODE_FIT will show the entire image, blown up as big as possibleSCALE_MODE_FILL will fill the entire page, at the cost of cropping the

image along one axis, if the image’s aspect ratio does not match the paper’s

aspect ratioprintBitmap() takes the name of the print job (so the user, when reviewing the

outstanding print jobs, knows what it is) and either a Uri or a Bitmap for

the image itself. In the case of a Uri, the Uri could be malformed, in which

case the FileNotFoundException may be thrown, which is why we catch it.

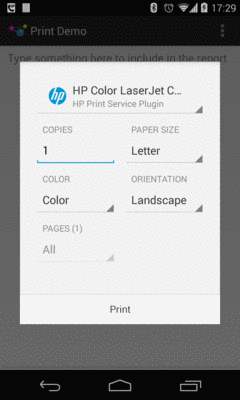

What the user sees, after choosing an image to print (and a printer, if the user has more than one available), is a print configuration dialog appear, much like those you might see in a desktop OS:

Figure 845: HP Print Configuration Dialog

The dialog itself is provided by Android; the contents of the dialog is provided

by a PrintService that is responsible for taking our print job and actually

dispatching it to the printer.

Here, the user can make typical changes, like portrait/landscape printing and the number of copies, before pressing the “Print” button. At that point, the user’s chosen image will be printed.

Note that, in Android 4.4, the print dialog does not work especially well in landscape on smaller screen sizes, forcing the user to scroll to get to all of the widgets, including the “Print” button.

Printing a bitmap is nice. It is not especially useful, as it implies that we have a bitmap worth printing by itself. That is certainly possible, but it is unlikely. Even in the case where we want to print a photo, there is a very good chance that we will need to print some additional information along with the photo (caption, date when photo was taken, etc.).

Being able to print something over which we have greater control of the rendering would be more useful. The easiest way to do that is to print some HTML. Later in this chapter we will cover how to generate some dynamic HTML representing what you want to print. For the moment, though, let’s focus on the printing itself.

Starting in API Level 19, WebView is capable of participating in the

print process. You can load up a WebView with your desired content, then

print that content.

Some apps will already be using a WebView as part of the UI, and that WebView

will contain what needs to be printed. For example, a Web browser can easily

add a “Print” action bar overflow item that would print the contents of the

active WebView in the browser.

For cases where you want to print something, but you are not using the WebView

for anything but printing, you do not need to add the WebView to the UI.

You can create a WebView instance via its constructor, passing in your Activity

as the Context required by that constructor. You can then populate that WebView

with what needs to be printed, then print it. That is the technique that the

sample application demonstrates, in part because it is likely to be the more

common scenario — only so many apps use a WebView in the UI, and more are likely

to need to print.

The sample app’s “Web Page” action bar overflow item is tied to an R.id.web

MenuItem. When that is tapped by the user, onOptionsItemSelected() calls

printWebPage() to print a Web page loaded from a URL:

private void printWebPage() {

WebView print=prepPrintWebView(getString(R.string.web_page));

print.loadUrl("https://commonsware.com/Android");

}

Here, getString(R.string.web_page) is returning a string resource that will

be used for the name of a print job. prepPrintWebView() returns the WebView

that will be used for printing. loadUrl() is the standard WebView method

for populating the WebView from a URL. Note that this causes the sample app

to need the INTERNET permission, since we are downloading a Web page and its

related assets (CSS, images) from the Internet.

You will notice that we are not actually printing anything directly in

printWebPage(), which may seem a bit odd given the name of the method. That

is because we cannot print anything until the page is loaded — after all, it is

only then that we have what we want to print.

The job of prepPrintWebView() is to arrange to get control when the page

is loaded and actually print the desired page:

private WebView prepPrintWebView(final String name) {

WebView result=getWebView();

result.setWebViewClient(new WebViewClient() {

@Override

public void onPageFinished(WebView view, String url) {

print(name, view.createPrintDocumentAdapter(),

new PrintAttributes.Builder().build());

}

});

return(result);

}

getWebView() is just a lazy-initialization method, populating a wv data

member of the activity with a WebView. This way, we avoid creating the WebView

up front, as if the user does not elect to print any HTML, we do not need the

WebView, and a WebView is expensive to initialize:

private WebView getWebView() {

if (wv == null) {

wv=new WebView(this);

}

return(wv);

}

We are holding onto the WebView in a data member to ensure that it will

not be garbage-collected. A WebView that is part of our UI is being strongly

held by its parent in the View hierarchy, so we do not normally need to worry

about this. However, in this case, we are creating a WebView dynamically and

are not adding it to the UI, so we are responsible for holding onto it, at least

as long as is needed. In this sample, we just hold onto it for the rest of the life

of the activity.

Back in prepPrintWebView(), we call setWebViewClient(), to attach an anonymous

inner class extending WebViewClient to the WebView. Back in

the chapter introducing WebView, we saw WebViewClient in the

context of shouldOverrideUrlLoading(). Another popular method to override on a

WebViewClient is onPageFinished(). This is called when the HTML and related

assets (CSS, images, etc.) have been loaded and rendered within the WebView. At

this point, for the particular URL we are loading, it is safe to print the

page.

In onPageFinished(), we call a print() method on MainActivity itself:

private PrintJob print(String name, PrintDocumentAdapter adapter,

PrintAttributes attrs) {

startService(new Intent(this, PrintJobMonitorService.class));

return(mgr.print(name, adapter, attrs));

}

The first line of print() calls startService() to start a PrintJobMonitorService.

We will see more about why we are doing that later in this chapter.

For the moment, take it on faith that this service will help ensure that our process

stays around long enough for our print job to finish.

The second line of print() calls a print() method on

a mgr data member. Here,

mgr is a PrintManager, initialized up in onCreate() of the activity,

by calling getSystemService(), asking for the PRINT_SERVICE, and casting the

result to be a PrintManager.

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.main);

prose=findViewById(R.id.prose);

mgr=(PrintManager)getSystemService(PRINT_SERVICE);

}

The print() method tells the PrintManager to go print something. print()

takes three parameters:

name parameter

to prepPrintWebView(). That parameter is marked final, so the call to

setWebViewClient() will include the value of that parameter in the

anonymous inner class’ implementation of onPageFinished().PrintDocumentAdapter. For the case of printing HTML, we get one of those

by calling createPrintDocumentAdapter() on our populated WebView.PrintAttributes object, describing any particular requirements that you

have for the printed output (e.g., media size, margins, color/monochrome). If you

will let the user control all of that via the print dialog, an empty PrintAttributes

is fine to use with print(). You typically create a PrintAttributes by

creating a PrintAttributes.Builder, calling setters on the Builder to configure

the PrintAttributes, and getting the resulting PrintAttributes via a call

to build().And that’s it. Android — in particular, WebView and its PrintDocumentAdapter –

takes over from here and prints the Web page.

Alas, we do not have infinite flexibility with printing HTML from a WebView.

Here are some limitations and potential problem areas that you will encounter:

onPageFinished()

does not take those operations into account. You will need to use

addJavascriptInterface() to inject a Java object into the JavaScript realm,

then have your asynchronous work arrange to call some method on that Java

object, to signal to you that the document is ready for printing.WebView can only do one print job at a time. Printing occurs asynchronously,

and so you have to be careful that you do not accidentally start off a second

print job while an earlier one is in process. The print() method returns a

PrintJob that you can use to monitor the print job status, and this object

will be covered in a bit more detail later in this chapter.

You may wish to set up a WebView pool, where you reuse an existing WebView

only if its associated PrintJob is completed, creating a new WebView

instance if there is no available WebView at the moment. Or, you might disable

printing options in the UI until the PrintJob is done, so you can reuse the

WebView. The sample app does none of this, to keep things simpler.<div> IDs) or by page numbers.

Hence, you need to load into the WebView exactly what you want to print, no

more, no less.Also, any direct use of PrintManager will only work on API Level 19. You will

need to ensure that you only try using it on API Level 19+ devices, using Java

version guard blocks. You will also need to set your build target

(i.e., compileSdkVersion in Android Studio) to at least

API Level 19 to be able to reference the PrintManager and related classes.

Finally, while loading and printing HTML are both intrinsically asynchronous, generating HTML locally is not. We will discuss this issue a bit more later in this chapter.

As will be seen in the next section, even if we “hand-roll”

our printed output using a Canvas, the result seems to be a PDF file. Hence,

you would think that the printing framework would provide convenience code to

print a PDF file that we obtained by other means.

Alas, that is not the case.

The sample app contains some code demonstrating how this is possible,

inspired by this Stack Overflow answer,

though

it may cut a few corners that Google would prefer not be cut. However, it also

illustrates how to create your own PrintDocumentHandler, which you will need

for any print job not involving a bitmap or HTML.

We supply a PrintDocumentAdapter to the print() method on PrintManager. In

the HTML case, we got a PrintDocumentAdapter from the WebView, and so it

is Google’s job to implement that adapter. Similarly, PrintHelper has its

own internal implementation of a PrintDocumentAdapter that it uses for printing

the bitmap.

For anything else, you need to create your own PrintDocumentAdapter, or

find a third-party implementation that you can perhaps reuse.

PrintDocumentAdapter’s job is to supply the PrintManager with the content

to be printed, in the form of a PDF file. To do that, there are four callback

methods that PrintManager (and related classes) will call on the

PrintDocumentAdapter:

onStart() is called first. If you are planning on using the same

PrintDocumentAdapter instance for multiple print jobs, this would be a spot

to initialize the work for a new job. Otherwise, if you were only planning

on using a PrintDocumentAdapter instance once, you may as well just put your

initialization logic in the constructor.onLayout() is called next. Here is where you do enough work to determine

what the resulting output will be later on as printing continues. In particular,

if you want to provide an accurate page count, this is where you will need

to perform the necessary calculations to determine that.onWrite() is called next, asking you to write one or more PDF pages out to

a supplied ParcelFileDescriptor (on which you can create an OutputStream).onFinish() is called last, when the printing request is completed, so you

can free up any necessary resources.All four of those callback methods are called on the main application thread.

Your onStart() and onFinish() methods need to be fast enough to complete

their work on that thread, and that may not be a problem. The work that

onLayout() and onWrite() do may take a while, though, and so the protocol

is designed to allow you to do that work on a background thread. Both methods

are passed a callback object that you use to pass along the results of your work,

and both are passed a CancellationSignal to indicate if the user cancels the

print job while you are doing the work.

What PrintDocumentAdapter does not do is actually give you a thread to use.

So, the sample app contains a ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter that moves

the onLayout() and onFinish() work to a background thread:

package com.commonsware.android.print;

import android.content.Context;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.os.CancellationSignal;

import android.os.ParcelFileDescriptor;

import android.print.PageRange;

import android.print.PrintAttributes;

import android.print.PrintDocumentAdapter;

import java.util.concurrent.ExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

abstract class ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter extends

PrintDocumentAdapter {

abstract LayoutJob buildLayoutJob(PrintAttributes oldAttributes,

PrintAttributes newAttributes,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

LayoutResultCallback callback,

Bundle extras);

abstract WriteJob buildWriteJob(PageRange[] pages,

ParcelFileDescriptor destination,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

WriteResultCallback callback,

Context ctxt);

private Context ctxt=null;

private ExecutorService threadPool=Executors.newFixedThreadPool(1);

ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter(Context ctxt) {

this.ctxt=ctxt;

}

@Override

public void onLayout(PrintAttributes oldAttributes,

PrintAttributes newAttributes,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

LayoutResultCallback callback, Bundle extras) {

threadPool.submit(buildLayoutJob(oldAttributes, newAttributes,

cancellationSignal, callback,

extras));

}

@Override

public void onWrite(PageRange[] pages,

ParcelFileDescriptor destination,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

WriteResultCallback callback) {

threadPool.submit(buildWriteJob(pages, destination,

cancellationSignal, callback, ctxt));

}

@Override

public void onFinish() {

threadPool.shutdown();

super.onFinish();

}

protected abstract static class LayoutJob implements Runnable {

PrintAttributes oldAttributes;

PrintAttributes newAttributes;

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal;

LayoutResultCallback callback;

Bundle extras;

LayoutJob(PrintAttributes oldAttributes,

PrintAttributes newAttributes,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

LayoutResultCallback callback, Bundle extras) {

this.oldAttributes=oldAttributes;

this.newAttributes=newAttributes;

this.cancellationSignal=cancellationSignal;

this.callback=callback;

this.extras=extras;

}

}

protected abstract static class WriteJob implements Runnable {

PageRange[] pages;

ParcelFileDescriptor destination;

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal;

WriteResultCallback callback;

Context ctxt;

WriteJob(PageRange[] pages, ParcelFileDescriptor destination,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

WriteResultCallback callback, Context ctxt) {

this.pages=pages;

this.destination=destination;

this.cancellationSignal=cancellationSignal;

this.callback=callback;

this.ctxt=ctxt;

}

}

}

This class uses a single-thread thread pool, managed by an ExecutorService.

In principle, a well-written PrintDocumentAdapter could handle multiple

print jobs in parallel — if you attempt this and are using

ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter for inspiration, simply increase the size

of the thread pool.

The onLayout() and onWrite() methods package up their parameters

(described in the next section) into job objects.

Those objects implement Runnable, and they are then handed to the ExecutorService

to be run on the next-available thread. onFinish() shuts down the ExecutorService,

though if you wanted to use the ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter for multiple

print jobs, you would come up with some other logic to clean up the

ExecutorService when you were done with all of the jobs.

Subclasses of ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter need to:

LayoutJob and WriteJob static inner classes,

implementing their respective

run() methods, to do the work required of onLayout() and onWrite()

buildLayoutJob() and buildWriteJob() methods that return

instances of those custom subclasses(fans of dependency injection no doubt can find better solutions for wiring

up a ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter)

However, we still need to actually be able to print a PDF, which

ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter does not do on its own. The sample app

also has a PdfDocumentAdapter, which extends ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter

and demonstrates a crude way of printing a PDF through the PrintDocumentAdapter

protocol.

PdfDocumentAdapter does not use onStart() or onFinish(). And, since

the onLayout() and onWrite() methods are handled by

ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter, PdfDocumentAdapter does not have those either.

It does, however, have the buildLayoutJob() and buildWriteJob() methods

required by ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter. These return instances of a

PdfLayoutJob and PdfWriteJob, respectively:

@Override

LayoutJob buildLayoutJob(PrintAttributes oldAttributes,

PrintAttributes newAttributes,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

LayoutResultCallback callback, Bundle extras) {

return(new PdfLayoutJob(oldAttributes, newAttributes,

cancellationSignal, callback, extras));

}

@Override

WriteJob buildWriteJob(PageRange[] pages,

ParcelFileDescriptor destination,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

WriteResultCallback callback, Context ctxt) {

return(new PdfWriteJob(pages, destination, cancellationSignal,

callback, ctxt));

}

PdfLayoutJob needs to fulfill the bulk of the onLayout() contract:

CancellationSignal and call onLayoutCancelled() on

the supplied LayoutResultCallback if the job has been canceledPrintDocumentInfo object to provide metadata about the document

to be printed, and pass that to onLayoutFinished() on the

LayoutResultCallback

private static class PdfLayoutJob extends LayoutJob {

PdfLayoutJob(PrintAttributes oldAttributes,

PrintAttributes newAttributes,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

LayoutResultCallback callback, Bundle extras) {

super(oldAttributes, newAttributes, cancellationSignal, callback,

extras);

}

@Override

public void run() {

if (cancellationSignal.isCanceled()) {

callback.onLayoutCancelled();

}

else {

PrintDocumentInfo.Builder builder=

new PrintDocumentInfo.Builder("CHANGE ME PLEASE");

builder.setContentType(PrintDocumentInfo.CONTENT_TYPE_DOCUMENT)

.setPageCount(PrintDocumentInfo.PAGE_COUNT_UNKNOWN)

.build();

callback.onLayoutFinished(builder.build(),

!newAttributes.equals(oldAttributes));

}

}

}

PdfLayoutJob also has access to two PrintAttributes objects, the “old”

attributes and the “new” attributes. In principle, onLayout() could be called

a couple of times, perhaps based upon changes the user makes in the print dialog.

These PrintAttributes objects describe the nature of the output, including

things like page size and margins. PdfLayoutJob totally ignores these, because

the PDF is a packaged asset in this case and cannot be changed. If you are

dynamically generating a PDF file, you may wish to pay attention to the

new PrintAttributes and take them into account.

PdfLayoutJob also has access to a Bundle of “extras”, not unlike the “extras”

associated with an Intent. At the present time, there is only one semi-documented

“extra”, EXTRA_PRINT_PREVIEW, which will be true if onLayout() is being

called to generate a print preview of the printed output, false otherwise.

What PdfLayoutJob does do is create a PrintDocumentInfo.Builder to set up

a PrintDocumentInfo object indicating that:

CONTENT_TYPE_DOCUMENT) versus a “photo”

(CONTENT_TYPE_PHOTO) or “unknown” (CONTENT_TYPE_UNKNOWN). This information

is passed to the PrintService that functions as a bridge between PrintManager

and the printer, and the PrintService might optimize output based upon this

setting (e.g., lower quality print output for a “document” instead of

a “photo”).PAGE_COUNT_UNKNOWN). In principle,

the page count is known, insofar as the PDF that will be printed is an asset

baked into the app, and so we could hard-code the page count in addition to

hard-coding other details (like the asset’s filename).The boolean second parameter to onLayoutFinished() is supposed to be true

if the layout changed, false otherwise. In practice, the value does not seem

to matter on the first onLayout() call. The implementation here compares

the two PrintAttributes objects using equals().

The last piece is the PdfWriteJob, which performs the work required of the

onWrite() callback:

private static class PdfWriteJob extends WriteJob {

PdfWriteJob(PageRange[] pages, ParcelFileDescriptor destination,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

WriteResultCallback callback, Context ctxt) {

super(pages, destination, cancellationSignal, callback, ctxt);

}

@Override

public void run() {

InputStream in=null;

OutputStream out=null;

try {

in=ctxt.getAssets().open("cover.pdf");

out=new FileOutputStream(destination.getFileDescriptor());

byte[] buf=new byte[16384];

int size;

while ((size=in.read(buf)) >= 0

&& !cancellationSignal.isCanceled()) {

out.write(buf, 0, size);

}

if (cancellationSignal.isCanceled()) {

callback.onWriteCancelled();

}

else {

callback.onWriteFinished(new PageRange[] { PageRange.ALL_PAGES });

}

}

catch (Exception e) {

callback.onWriteFailed(e.getMessage());

Log.e(getClass().getSimpleName(), "Exception printing PDF", e);

}

finally {

try {

in.close();

out.close();

}

catch (IOException e) {

Log.e(getClass().getSimpleName(),

"Exception cleaning up from printing PDF", e);

}

}

}

}

At its core, PdfWriteJob simply writes our PDF (culled from a cover.pdf asset)

to an OutputStream. The OutputStream is built from the ParcelFileDescriptor,

indicating where the PDF content should be written to.

The InputStream-to-OutputStream “bucket brigade” is augmented with checks on

the CancellationSignal, to abandon the loop if the print job was canceled by

the user. At the end, we call one of three methods on the WriteResultCallback:

onWriteCancelled() if the CancellationSignal indicates that the job

was canceledonWriteFinished() if everything succeededonWriteFailed() (with an error message) if there was some problem, such as

failed I/OPdfWriteJob has access to a PageRange array, representing the particular pages

out of a larger document to be printed. The parameter to onWriteFinished()

is another PageRange array that should indicate what pages were printed. Once

again, since the PDF is fixed, PdfWriteJob ignores the input PageRange array,

and it indicates that we wrote all pages (PageRange.ALL_PAGES) in the output.

In principle, if you have more control over your environment, you should only

print the requested pages, in which case the output parameter to onWriteFinished()

might be the same array as was passed into onWrite().

Back in MainActivity, the “PDF” action bar overflow item triggers a call to

print() on the PrintManager, supplying our PdfDocumentAdapter and another

empty PrintAttributes:

case R.id.pdf:

print("Test PDF",

new PdfDocumentAdapter(getApplicationContext()),

new PrintAttributes.Builder().build());

The PdfDocumentAdapter needs a Context, in order to access the cover.pdf

asset. If your PDF file is being generated, or is saved as a file on external

storage, you would not need this. Since it is theoretically possible that our

activity could be destroyed while the printing is going on in background threads,

rather that briefly leak an Activity, we provide the Application Context

to PdfDocumentAdapter, as that is a singleton and cannot be leaked.

The result of all of this is that when the user chooses the “PDF” action bar overflow item, the book cover copy is printed.

What Google really wants you to do — if bitmaps and HTML are insufficient –

is to create PDF documents using PrintedPdfDocument and a Canvas.

The concept is simple:

PrintedPdfDocument instance, given a PrintAttributes that describes

the page size, margins, etc.startPage() to add a page to the document, which returns a

PdfDocument.Page

getCanvas() on the Page and use the standard Android 2D drawing APIs

to draw lines, text, shaded areas, and so forthfinishPage() on the PdfPrintedDocument when you are done rendering

that pagewriteTo() on the PrintedPdfDocument to write the PDF to an OutputStream,

such as the one you get from the ParcelFileDescriptor in the onWrite()

callback of your PrintDocumentAdapter

close() on the PrintedPdfDocument when you are doneFor example, let’s look at the onWrite() implementation used by PrintHelper

to print a bitmap:

@Override

public void onWrite(PageRange[] pageRanges, ParcelFileDescriptor fileDescriptor,

CancellationSignal cancellationSignal,

WriteResultCallback writeResultCallback) {

PrintedPdfDocument pdfDocument = new PrintedPdfDocument(mContext,

mAttributes);

try {

Page page = pdfDocument.startPage(1);

RectF content = new RectF(page.getInfo().getContentRect());

// Compute and apply scale to fill the page.

Matrix matrix = getMatrix(mBitmap.getWidth(), mBitmap.getHeight(),

content, fittingMode);

// Draw the bitmap.

page.getCanvas().drawBitmap(mBitmap, matrix, null);

// Finish the page.

pdfDocument.finishPage(page);

try {

// Write the document.

pdfDocument.writeTo(new FileOutputStream(

fileDescriptor.getFileDescriptor()));

// Done.

writeResultCallback.onWriteFinished(

new PageRange[]{PageRange.ALL_PAGES});

} catch (IOException ioe) {

// Failed.

Log.e(LOG_TAG, "Error writing printed content", ioe);

writeResultCallback.onWriteFailed(null);

}

} finally {

if (pdfDocument != null) {

pdfDocument.close();

}

if (fileDescriptor != null) {

try {

fileDescriptor.close();

} catch (IOException ioe) {

/* ignore */

}

}

}

}

(note: the preceding code snippet is Copyright (C) 2013 The Android Open Source Project)

Here, they:

PrintedPdfDocument

startPage()

Matrix based upon the image size, the page size,

and the scale type (FIT or FILL)Canvas using that Matrix

OutputStream for the supplied ParcelFileDescriptor

Curiously, they do not do this work in a background thread, though the

onLayout() implementation does use a background thread (since the image

Uri may require an Internet download).

If you are comfortable with the Canvas API, writing PDF pages is much

the same as drawing to your custom View. On the other hand, Android’s

Canvas API is not the same as any other drawing system’s API, so

there will be distinct differences from any other 2D drawing API that

you might have used previously.

The print() method that we have been calling on PrintManager returns

a PrintJob, representing the print job. This object has a number of

status inquiry methods, including (in rough order of when the events occur):

isStarted()isQueued() (i.e., waiting for the print system to process it)isBlocked() (i.e., permanently stuck, but needs to be canceled)isCompleted()isFailed()isCancelled()It also has a cancel() method that you can call to cancel the print job (e.g.,

based on user request). PrintJob also offers a restart() method that

you can use to re-try a failed (but not canceled) print job.

What PrintJob does not have is a listener interface to be proactively notified

when the job changes state.

PrintManager also has getPrintJobs(), which will return a list of the

PrintJob objects representing the jobs you have requested in this process,

rather than having to keep track of all of those yourself.

If you are going to create a report in HTML,

you will want to consider doing that work in an AsyncTask’s doInBackground()

method, so the I/O involved in creating the report happens in the background.

However, PrintManager requires that print() be called on the main application

thread, so you would call print() from onPostExecute() of the AsyncTask.

Similarly, if you are creating your own PrintDocumentAdapter, you will want

to consider moving the onLayout() and onWrite() work into background

threads, such as is illustrated in the sample app via ThreadedPrintDocumentAdapter.

The problem with bare threads or an AsyncTask is that they do not indicate

to Android that your process is still doing some work. It is possible that the

user could request that you print something, then switch to another app (e.g., HOME,

recent-tasks list). Android might consider your process to be relatively

low priority and could terminate it before your print job completes.

The obvious solution is to involve a service, perhaps even a foreground service, to indicate to Android that your process is doing work that the user will notice if it does not complete. You could start the service when you do the print job, and then stop the service when the print job is completed, to return your process to normal priority.

However, actually having a service do the printing is a serious pain:

WebView’s PrintDocumentAdapter really wants the Context that created

the WebView to be an Activity

onLayout() and onWrite() are not Parcelable and

so cannot be passed in Intent extras via startService() to the serviceOne possibility would be to create a PrintJobMonitorService, which is what

the sample app does. PrintJobMonitorService takes advantage of that

listPrintJobs() method on PrintManager to keep tabs on all of our

requested print jobs. So long as there is one or more print jobs in an active

state, the service keeps running. Otherwise, the service stops. Hence, while

the service is not actually doing the printing, it is running while the printing

is going on, flagging to the OS to leave our process alone during this critical

juncture.

package com.commonsware.android.print;

import android.app.Service;

import android.content.Intent;

import android.os.IBinder;

import android.os.SystemClock;

import android.print.PrintJob;

import android.print.PrintJobInfo;

import android.print.PrintManager;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

import java.util.concurrent.ScheduledExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class PrintJobMonitorService extends Service implements Runnable {

private static final int POLL_PERIOD=3;

private PrintManager mgr=null;

private ScheduledExecutorService executor=

Executors.newSingleThreadScheduledExecutor();

private long lastPrintJobTime=SystemClock.elapsedRealtime();

@Override

public void onCreate() {

super.onCreate();

mgr=(PrintManager)getSystemService(PRINT_SERVICE);

executor.scheduleAtFixedRate(this, POLL_PERIOD, POLL_PERIOD,

TimeUnit.SECONDS);

}

@Override

public int onStartCommand(Intent intent, int flags, int startId) {

return(super.onStartCommand(intent, flags, startId));

}

@Override

public void onDestroy() {

executor.shutdown();

super.onDestroy();

}

@Override

public void run() {

for (PrintJob job : mgr.getPrintJobs()) {

if (job.getInfo().getState() == PrintJobInfo.STATE_CREATED

|| job.isQueued() || job.isStarted()) {

lastPrintJobTime=SystemClock.elapsedRealtime();

}

}

long delta=SystemClock.elapsedRealtime() - lastPrintJobTime;

if (delta > POLL_PERIOD * 2) {

stopSelf();

}

}

@Override

public IBinder onBind(Intent intent) {

return(null);

}

}

PrintJobMonitorService uses a single-thread ScheduledExecutorService, to get

control every three seconds in its run() method. The run() method iterates

over the PrintJob objects associated with our app and looks for any that are

in one of three states:

The first two states have simple test methods on PrintJob (isStarted() and

isQueued()). The “created” state does not, for some reason, so we have to get

the underlying PrintJobInfo object and manually check its state (getState())

to see if it is started (PrintJobInfo.STATE_STARTED).

PrintJobMonitorService tracks the last time we saw an in-progress print job.

If we have gone through two three-second polling periods without any in-progress

print jobs, the service assumes that it is no longer needed and calls stopSelf().

Before Android 4.4, printing in Android was limited and clunky.

The primary approach was to use Google Cloud Print. In effect, Google Cloud

Print is a Web-managed print server. You would teach Google how to talk to

your printers, and then any authorized device could print to those

printers. By sharing your content (particularly PDFs) via ACTION_SEND,

the user could choose Google Cloud Print as an option if they had

Google Cloud Print set up for their device and printer. Note that

the Android 4.4 printing framework includes a PrintService that works

with Google Cloud Print, so users who have set up Google Cloud Print can

still use it even with the new printing framework.

Various printer manufacturers or third parties also created their own apps that would fill a similar role, albeit perhaps working with printers on the local network. Or, you could write your own low-level code to talk to a network printer via relevant printing protocols like IPP, though this would be unpleasant at best.

Earlier in this chapter, we saw how to print HTML. However,

the HTML we printed was loaded from a URL. That is fine, but, as with printing

bitmaps, it may not be a very popular scenario. What will be more likely is that

you want to print some sort of report, generated on the device. And, since

printing using the Canvas is a bit complicated, creating the report via HTML

may be an easier route to take.

The typical approach for this involves creating an HTML template that sets up the basic page (e.g., references to CSS), then uses some sort of “macros” in the template to indicate portions that should be replaced dynamically with something from outside of the template.

This approach has been used since the early days of the original “dot-com revolution” of the 1990’s, pioneered by tools like Cold Fusion. In Java, there are any number of available template engines.

However, for HTML, it is reasonably likely that a Web designer is going to want to get involved, to style the report. Ideally, you choose a template engine that is either something the designer is already using, or is one that is something the designer might wish to use elsewhere in the future. Forcing the designer to learn some new template syntax, just for the purposes of creating these reports, may not be the best use of the designer’s time (or your time, for answering all of the designer’s questions).

One of the more popular template structures used today use braces (a.k.a., curly

brackets) as the macro delimiters (e.g., {{ something }}). In particular,

the macro syntax popularized by mustache is used

by many template engine implementations. There is a very good chance that your

Web designer already has used mustache-style templates, or at least has heard

about them.

And, conveniently enough, there is a Java implementation – jmustache — that is Android-friendly. The sample app in this chapter implements a “TPS Report” that is generated from a mustache template using jmustache.

The “Get It” section of the jmustache documentation contains up-to-date instructions for adding it to a project.

Developers using the Android Gradle Plugin — including Android Studio users –

should reference the Maven Central artifact (com.samskivert:jmustache) from

build.gradle.

A report template for jmustache can be a String or a Reader, with the latter

allowing you to pull in files, assets, or raw resources (the latter two via an

InputStreamReader).

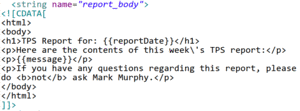

In the case of the sample app, the template is small, and is packaged as a string

resource. However, since the template involves HTML tags, we have to use CDATA

notation to allow those tags to be left alone within the XML of the string

resource:

Figure 846: TPS Report Mustache Template

The template contains {{reportDate}} and {{message}} variables to be replaced

at runtime with dynamic data from our app. Also note that, despite the CDATA,

we still need to escape the apostrophe with a leading backslash (\').

What will fill in the {{reportDate}} and {{message}} variables will be values

from a “context”. Here, “context” is not referring to Context, but rather an

object that we pass to jmustache to serve as the source of data to blend into

the report.

jmustache has fairly flexible rules for how it can resolve template variables,

including calling Java getter methods based on the variable names. Hence,

we can create a “context” that has getReportDate() and getMessage()

methods, such as the TpsReportContext class in the sample app:

private static class TpsReportContext {

private static final SimpleDateFormat fmt=

new SimpleDateFormat("yyyy-MM-dd", Locale.US);

String msg;

TpsReportContext(String msg) {

this.msg=msg;

}

@SuppressWarnings("unused")

String getReportDate() {

return(fmt.format(new Date()));

}

@SuppressWarnings("unused")

String getMessage() {

return(msg);

}

}

The “TPS Report” action bar overflow item eventually routes to a

printReport() method on MainActivity:

private void printReport() {

Template tmpl=

Mustache.compiler().compile(getString(R.string.report_body));

WebView print=prepPrintWebView(getString(R.string.tps_report));

print.loadData(tmpl.execute(new TpsReportContext(prose.getText()

.toString())),

"text/html; charset=UTF-8", null);

}

The first statement creates a jmustache Template object representing the

report template. This is created by getting the singleton compiler() from

Mustache, and calling compile() on it to interpret the string resource.

Note that since this Template only depends upon the string resource, we could

cache the Template, rebuilding it only on configuration changes, if desired.

Note that we load the template on the main application thread, as printReport()

is called from onOptionsItemSelected(). For a small string resource, that is OK.

If you are loading a more complex report template, you will want to do that in

a background thread.

The second statement mirrors one from printing the Web page from before, where

we call prepPrintWebView() to lazy-create our WebView and set it up to print

when the page is loaded. Here, we use a different print job name than before, one

reflecting the fact that this is a TPS report.

Finally, we use execute() on the Template to generate our HTML for printing,

then pass that HTML to the loadData() method on WebView. execute() takes

our “context” Object, which in this case is an instance of our TpsReportContext

class, with the value typed into the EditText widget in our UI as the “message”

to go into the report.

Note that we execute() the Template on the main application thread as well as

having loaded it on that thread in the first place. Once again, the more complex

the report, the more likely it is that you will want to move this logic into a

background thread. However, remember that print() needs to be called on the main

application thread.

The result is that the user gets a printed TPS report, containing today’s date and

whatever message they typed into the EditText.

Perhaps you feel that generating HTML does not give you enough control,

yet using the Canvas options directly was too much control. Perhaps you

then think that generating a PDF to print, using something other than PdfDocument,

is the right answer. Or perhaps you are generating a PDF for other reasons, such

as to use with ACTION_SEND as output from your app.

You have two basic options for getting this PDF: generate it on the device, or offload the generation to a server.

There are various open source and commercial libraries

for generating PDF on Android. The best-known open source Java PDF library –

iText — has as dedicated Android version

(iTextG), though the AGPL license

may make it unsuitable for your use case. The commercial libraries range

from fixed-price to per-device licenses. How much advantage these have over

using PrintedPdfDocument from the Android SDK depends upon your needs.

If the bulk of the data needed for generating the PDF resides on a server, rather than downloading that data and using an underpowered Android device to create the PDF, you could upload the device-specific data to the server, have it create the PDF, and download the result from the server. There are plenty of server-side PDF generation tools, ranging from open source (e.g., wkhtmltopdf, unoconv, prawn) to commercial (e.g., Prince, used to generate the PDF edition of this book). You also get to work in your preferred programming language, in case that is not Java, and perhaps leverage the PDF generation logic for other uses (e.g., generate reports from your Web app).