Chapter II.1.5

Tissues, the Extracellular Matrix, and Cell–Biomaterial Interactions

This chapter will extend the concepts discussed previously in Chapter II.1.4 (Cells, Cell Function and Cell Injury) to describe how cells are organized to form specialized tissues and organs, how environmental stimuli affect tissue structure and function, how tissues respond to various insults, including those related to the insertion of biomaterials, and how cells interact with extracellular matrix and biomaterials. Four general areas will be covered:

1. Principles governing the structure and function of normal tissue, organs, and systems;

2. Processes leading to and resulting from abnormal (injured or diseased) tissues and organs;

3. Concepts in cell–biomaterials interactions;

4. Approaches to study the structure and function of tissues.

Germane to this discussion are two basic definitions: histology is the microscopic study of tissue structure; pathology is the study of the molecular, biochemical, and structural alterations and their consequences in diseased tissues and organs, and the underlying mechanisms that cause these changes. The mainstay of both histology and pathology is microscopic examination of tissues, aided by stains and other methods that enhance tissue contrast, indicate specific chemical and molecular moieties present, and convey structural and functional information.

Cells and extracellular matrix comprise the structural elements of the tissues of the body. The structure of cells, tissues, and organs comprise the morphologic expression of the complex (and dynamic) activities that comprise body function. The underlying theme is that structure is adapted to perform specific functions (conversely, changes in function may alter structure). Some excellent general references on tissue biology and pathology are available (Rubin and Strayer 2012; Kumar et al., 2010).

Cells and extracellular matrix are the structural elements of the tissues of the body. The structure of cells, tissues, and organs comprise the morphologic expression of the complex (and dynamic) activities that comprise body function. The underlying theme is that structure is adapted to perform specific functions (conversely, changes in function may change and alter structure).

Structure and Function of Normal Tissues

Cells, the living component of the body (as discussed in detail in the Chapter II.1.4), are surrounded by and obtain their nutrients and oxygen, and discharge wastes via blood, tissue fluid (also known as extracellular fluid), and lymph. Blood consists of blood cells suspended in a slightly viscous fluid called plasma; serum results when the coagulation proteins are removed from plasma, Capillaries exude a clear watery liquid called tissue fluid that permeates the amorphous intercellular substances lying between capillaries and cells. More tissue fluid is produced than can be absorbed back into the capillaries; the excess is carried away as lymph by a series of vessels called lymphatics, which ultimately empty the lymph into the bloodstream.

In all tissues and organs, cells are assembled during embryonic development into coherent groupings by virtue of specific cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions (Ingber, 2010a). Each type of tissue has a distinctive and genetically-determined pattern of structural organization adapted to its particular function; each pattern is strongly influenced by both metabolic (Carmeliet, 2003) and/or mechanical factors (Wozniak and Chen, 2009). Homeostasis, a normal process by which cells adjust their function to adapt to minor changes in day-to-day physiological demands, is regulated by:

1. Genetic programs of metabolism, differentiation, and specialization;

2. Influences of neighboring cells, the extracellular matrix, and signals that trigger specific cellular responses;

3. Environmental conditions, such as mechanical forces, temperature, and ionic content;

4. Availability of oxygen and metabolic substrates.

When normal limits of homeostasis are exceeded, pathological changes may result.

The Need for Tissue Perfusion

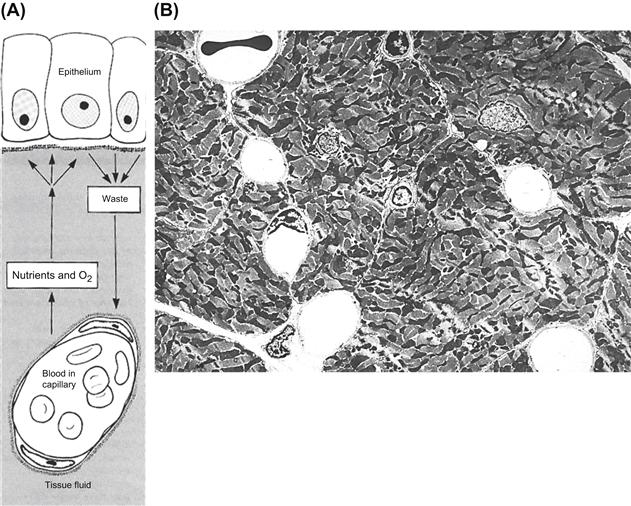

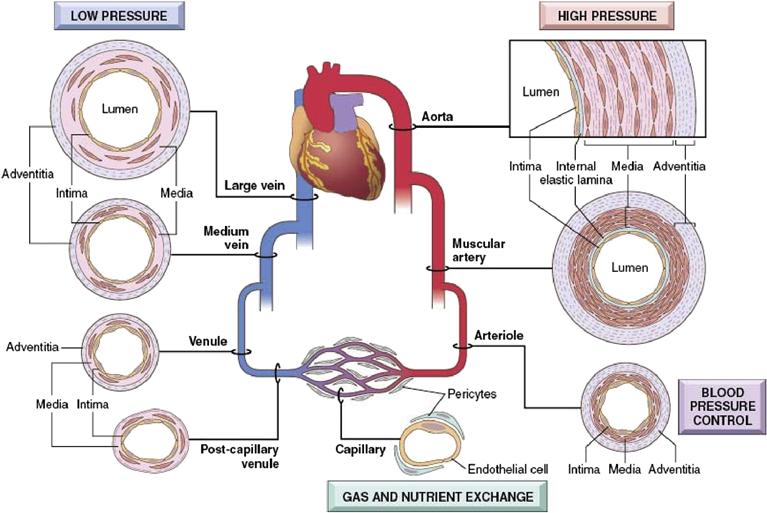

Since all mammalian cells require perfusion (i.e., blood flow bringing oxygen and nutrients, and carrying away wastes) for their survival, most tissues have a rich vascular network. Thus, the circulatory (also known as the cardiovascular) system is a key feature of tissue and organ structure and function (Figure II.1.5.1). Perfusion (i.e., delivery of blood) to a tissue or an organ is provided by the cardiovascular system, composed of a pump (the heart), a series of distributing and collecting tubes (arteries and veins), and an extensive system of thin walled vessels (capillaries) that permit exchange of substances between the blood and the tissues. Circulation of blood transports and distributes essential substances to the tissues, and removes byproducts of metabolism. Implicit in these functions are the intrinsic capabilities of the cardiovascular system to buffer pulsatile flow in order to ensure steady flow in the capillaries, regulate blood pressure and volume at all levels of the vasculature, maintain circulatory continuity while permitting free exchange between capillaries/venules and the extravascular compartments, and control hemostasis (managing hemorrhage by a coordinated response of vasoconstriction and plugging of vascular defects by coagulation and platelet clumps). Other functions of the circulation include such homeostatic (control) mechanisms as regulation of body temperature, and distribution of various regulating substances (e.g., hormones, cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, growth factors). Moreover, the circulatory system distributes immune and inflammatory cells to their sites of action, and the endothelial cells that line blood vessels have important immunological and inflammatory functions (Mitchell and Schoen, 2010).

FIGURE II.1.5.1 Role of the vasculature in tissue function. (A) Schematic diagram of the route by which the cells in a tissue obtain their nutrients and oxygen from underlying capillaries. Metabolic waste products pass in the reverse direction and are carried away in the bloodstream. In each case, diffusion occurs through the tissue fluid that permeates the amorphous intercellular substances lying between the capillaries and the tissue cells. (B) Myocardium, a highly metabolic tissue, has a rich vascular/capillary network, as demonstrated by transmission electron microscopy. The six open round spaces are capillaries. A red blood cell is noted in the capillary at upper left. ((A): Reproduced by permission from Cormack, D. H. (1987). Ham’s Histology, 9th Edn. Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA.)

Although the cardiac output is intermittent owing to the cyclical nature of the pumping of the heart, continuous flow to the periphery occurs by virtue of distention of the aorta and its branches during ventricular contraction (systole), and elastic recoil of the walls of the aorta and other large arteries with forward propulsion of the blood during ventricular relaxation (diastole). Blood moves rapidly through the aorta and its arterial branches, which become narrower and whose walls become thinner and change histologically toward the peripheral tissues. By adjusting the degree of contraction of their circular muscle coats, the distal arteries (arterioles) control the distribution of tissue blood flow to various tissues, and also permit regulation of local and systemic blood pressure. Blood returns to the heart from the capillaries, the smallest and thinnest walled vessels, by passing through venules and then through veins of increasing size.

Blood entering the right ventricle of the heart via the right atrium is pumped through the pulmonary arterial system at mean pressures about 1/6 of those developed in the systemic arteries. The blood then passes through the lung capillaries in the alveolar walls, where carbon dioxide is released across the pulmonary alveolar septa to, and oxygen taken up from, the alveoli. The oxygen-rich blood returns through the pulmonary veins to the left atrium and ventricle to complete the cycle.

Large diameter blood vessels are effective in delivering blood. Smaller vessels are most effective in regulating blood flow, and the smallest (the capillaries) regulate diffusional transport to and from the surrounding tissues. Thus, owing to their very thin walls and slow velocity of blood flow, which falls to approximately 0.1 cm/sec from 50 cm/sec in the aorta, capillaries are the sites of most exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and cellular wastes. Capillary density is determined by the diffusion limit of oxygen; approximately 100–200 μm in most highly metabolic tissues (recall Figure II.1.5.1). Thus, highly metabolic tissues (e.g., heart muscle) have a dense network of blood vessels, and three-dimensional tissue formation and growth requires the formation of new blood vessels, a process called angiogenesis. It also follows that tissues that require less nutrition (e.g., cartilage and resting skeletal muscle) and those that are relatively thin (e.g., heart valve leaflets) may either require a sparse vascular network or none at all.

In the following sections we will cover the general functional principles of tissue organization and response to various types of injury, highlighted by specific illustrative examples.

Extracellular Matrix

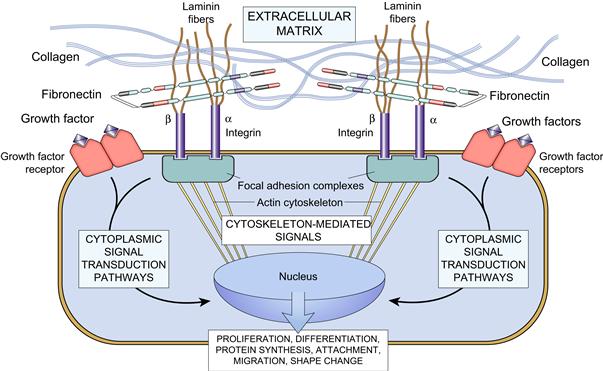

Extracellular matrix (ECM) comprises the biological material produced by, residing in-between, and supporting cells. ECM, cells, and capillaries are physically and functionally integrated in tissues and organs (Figure II.1.5.2). The ECM provides physical support and a matrix in which cells can adhere, signal each other, and interact. However, the ECM is more than a scaffold that maintains tissue and organ structure. Indeed, the ECM regulates many aspects of cell behavior, including cell proliferation and growth, survival, change in cell shape, migration, and differentiation (the so-called “cell fate decisions”). (See Figures II.1.5.3 and II.1.5.4.)

FIGURE II.1.5.2 Main components of the extracellular matrix, including collagen, proteoglycans, and adhesive glycoproteins. Both epithelial cells and fibroblasts interact with ECM via integrins. Basement membranes and interstitial ECM have differing architecture and general composition, although there is some overlap. Some ECM components (e.g., elastin) are not included for the sake of simplification. (Reproduced by permission from Kumar, V., Abbas, A. K., Fausto, N. & Aster, J. C. (eds.). (2010). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th Edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA.)

The principal functions of the ECM are:

• Mechanical support for cell anchorage

• Determination of cell orientation

• Maintenance of cell differentiation

• Scaffolding for orderly tissue renewal

• Establishment of tissue microenvironments

• Sequestration, storage, and presentation of soluble regulatory molecules.

Some extracellular matrices are specialized for a particular function, such as strength (tendon), filtration (the basement membranes in the kidney glomerulus) or adhesion (basement membranes supporting most epithelia). To produce additional mechanical strength in bones and teeth, the ECM is calcified. Even in a tissue as “simple” as a heart valve leaflet, the coordinated interplay of several ECM components, and the spatial and temporal dynamics of these interactions, are critical to function (Schoen, 2008). Moreover, the scaffolds used in tissue engineering applications often replicate the several functions of, and are intended to stimulate the production of, natural ECM (Lutolf and Hubbell, 2005; Lutolf et al, 2009).

ECM components are synthesized, secreted, and remodeled by cells in response to environmental cues. Virtually all cells secrete and degrade ECM to some extent. Certain cell types (e.g., fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells) are particularly active in production of interstitial ECM (i.e., the ECM between cells). Epithelial cells also synthesize the ECM of their basement membranes (see Figure II.1.5.5D).

Determinants of Tissue Form and Function

The mechanical forces that cells experience from their surroundings markedly influence the maintenance of cellular phenotypes, and affect cell shape, orientation, and differentiated function through interaction with receptors for specific ECM molecules on cell surfaces (such as integrins) (Chen, 2008; Mammoto and Ingber, 2010; Reilly and Engler, 2010). The resultant changes in cytoskeletal organization and in the production of second messengers can modify gene expression. ECM plays a critical role in cell differentiation, organogenesis, and as a scaffold allowing orderly repair following injury. The reciprocal instructions between cells and ECM are termed dynamic reciprocity

The ECM provides physical support and a matrix in which cells can adhere, signal each other, and interact. However, the ECM is more than a scaffold that maintains tissue and organ structure. Indeed, the ECM regulates many aspects of cell behavior, including cell proliferation and growth, survival, change in cell shape, migration and differentiation (the so-called “cell fate decisions”).

ECM consists of large molecules synthesized by cells, exported to the intercellular space, and structurally linked. Present to some degree in all tissues, and particularly abundant as an intercellular substance in connective tissues, ECM is composed of: (1) fibrous structural and adhesive proteins (e.g., collagen, laminins, fibronectin, vitronectin, and elastin); (2) specialized proteins (including growth factors); and (3) a largely amorphous interfibrillary matrix (mainly proteoglycans, solutes, and water). The precise composition varies from tissue to tissue. The large fibrous molecules are interlinked within an expansile glycoprotein–water gel, resembling a fiber-reinforced composite. The specific components are described below.

Fibrillar Proteins: Collagens and Elastin

Collagen comprises a family of closely related but genetically, biochemically, and functionally distinct molecules, which are responsible for tissue tensile strength. The most common protein in the animal world, collagen provides the extracellular framework for all multicellular organisms. The collagens are composed of a triple helix of three polypeptide α chains; about 30 different α chains form approximately 20 distinct collagen types. Types I, II, and III are the interstitial or fibrillar collagens; they are the most abundant and the most important for the present discussion. Type I is ubiquitous in hard and soft tissues; Type II is rich in cartilage, intervertebral disk, and the vitreous of the eye; and Type III is prevalent in soft tissues, especially those regions that are healing following injury, and in the walls of hollow organs. Types IV and V are nonfibrillar and are present in basement membranes, and soft tissues and blood vessels, respectively. Collagens are: (1) synthesized in cells as soluble procollagen precursors in discrete protein subunits; (2) secreted into the extracellular environment self-assembled; and (3) matured insoluble collagen molecules in the extracellular space (called “post-translational modification”).

During collagen synthesis, the α chains are subjected to a number of enzymatic modifications, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine residues, providing collagen with a high content of hydroxyproline (10%). Vitamin C is required for hydroxylation of the collagen propeptide; a requirement that explains inadequate wound healing in vitamin C deficiency (scurvy). After the modifications, but still inside the cell, the procollagen chains align and form the triple helix. However, the procollagen molecule is still soluble and contains N-terminal and C-terminal propeptides. During or shortly after secretion from the cell, procollagen peptidases clip the terminal propeptide chains, promoting formation of fibrils, often called tropocollagen, and oxidation of specific lysine and hydroxylysine residues occurs by the extracellular enzyme lysyl oxidase. This results in cross-linkages between α chains of adjacent molecules stabilizing the array that is characteristic of collagen. The mechanical properties of collagen reflect this structure; collagen fibrils are both non-extensible even at very high loads, and incompressible.

Elastic fibers are composed of the protein elastin. They confer passive recoil to various tissues, are critical components of vascular tissues (especially the aorta where repeated pulsatile flow would cause unacceptable shears on non-compliant tissue and elastic recoil is important), and of intervertebral disks (where the repetitive forces of ambulation along the spine are dissipated). Unlike collagen, elastin can be stretched). The stretching of an artery every time the heart pumps blood into an artery is followed by the recoil of elastin which restores the artery’s former diameter between heartbeats.

Amorphous Matrix: Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), Proteoglycans, and Hyaluronan

Amorphous intercellular substances contain carbohydrate bound to protein. The carbohydrate is in the form of long chain polysaccharides called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). When GAGs are covalently bound to proteins, the molecules are called proteoglycans. GAGs are highly charged (usually sulfated) polysaccharide chains up to 200 sugars long, composed of repeating unbranched disaccharide units (one of which is always an amino sugar – hence the name glycosaminoglycan). GAGs are divided into four major groups on the basis of their sugar residues:

• Hyaluronic acid: a component of loose connective tissue and of joint fluid, where it acts as a lubricant;

• Chrondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate;

With the exception of hyaluronic acid (not sulfated and thereby unique among the GAGs), all GAGs are covalently attached to a protein backbone to form proteoglycans, with a structure that schematically resembles a bottle brush. Proteoglycans are diverse, owing to different core proteins and different glycosaminoglycans. Proteoglycans are named according to the structure of their principal repeating disaccharide. Some of the most common are heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, and dermatan sulfate. Proteoglycans can also be integral membrane proteins, and are thus modulators of cell growth and differentiation. The syndecan family has a core protein that spans the plasma membrane and contains a short cytosolic domain, as well as a long external domain to which a small number of heparan sulfate chains are attached. Syndecan binds collagen, fibronectin, and thrombospondin in the ECM, and can modulate the activity of growth factors. Hyaluronan consists of many repeats of a simple disaccharide stretched end-to-end and binds a large amount of water, forming a viscous hydrate gel, which gives connective tissue turgor pressure and an ability to resist compression forces. This ECM component helps provide resilience, as well as a lubricating feature to many types of connective tissue, notably that found in the cartilage in joints.

Adhesive Molecules

Adhesive proteins, including fibronectin, laminin, and entactin permit the attachment to, and movement of, cells within the ECM.

• Fibronectin is a ubiquitous, multi-domain glycoprotein possessing binding sites for a wide variety of other ECM components. It is synthesized by many different cell types, with the circulating form produced mainly by hepatocytes. Fibronectin is important for linking cells to the ECM via cell surface integrins. Fibronectin’s adhesive character also makes it a crucial component of blood clots, and of pathways followed by migrating cells. Thus, fibronectin-rich pathways guide and promote the migration of many kinds of cells during embryonic development and wound healing.

• Laminin is an extremely abundant component of the basement membrane; it is a tough, thin, sheet-like layer on which epithelial cells sit, and is important for cell differentiation, adhesion to the substrate, and tissue remodeling. Laminin polypeptides are arranged in the form of an elongated cross, with individual chains held together by disulfide bonds. Like fibronectin, laminin has a distinct domain structure; different regions of the molecule bind to Type IV collagen (an important component of the basement membrane), heparin sulfate, entactin (a short protein that cross-links each laminin molecule to Type IV collagen), and cell surface integrins.

Extracellular Matrix Remodeling

The maintenance of the extracellular matrix requires ongoing remodeling of collagen, itself dependent on ongoing collagen synthesis and catabolism. Connective tissue remodeling, either physiological or pathological, is in most cases a highly organized and regulated process that involves the selective action of a group of related proteases that collectively can degrade most, if not all, components of the extracellular matrix. These proteases are known as the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Subclasses include the interstitial collagenases, stromelysins, and gelatinases.

In many tissues, cells degrade and reassemble the ECM in response to external signals as part of physiological homeostasis in mature, healthy tissues. Although matrix turnover is generally quite low in normal mature tissues, rapid and extensive remodeling characterizes embryological development (which involves branching morphogenesis, and stem cell homing, proliferation and differentiation), and wound repair, as well as various adaptive and pathologic states, such as tumor cell invasion and metastasis. ECM remodeling is mediated (and regulated) by signaling through ECM receptors, including the integrins and the ECM-modifying proteins, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), serene proteases (e.g., plasmin, plasminogen activator), and cysteine protease (e.g., cathepsins) (Page-McCaw et al., 2007; Daley et al., 2008). An understanding of cell–substrate interactions and matrix remodeling are central to the application of next-generation biomaterials technology, tissue engineering, and regenerative therapeutics (Gurtner et al., 2008).

Enzymes that degrade collagen are synthesized by macrophages, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells. Collagenases are specific for particular types of collagens, and many cells contain two or more different such enzymes. For example, fibroblasts synthesize a host of matrix components, as well as enzymes involved in matrix degradation, such as MMPs and serine proteases. Particularly important in tissue remodeling are myofibroblasts, a particular phenotype of cells that are characterized by features of both smooth muscle cells (e.g., contractile proteins such as α-actin) and features of fibroblasts (e.g., rough endoplasmic reticulum in which proteins are synthesized) (Hinz et al., 2007). These cells may also be responsible for the production of (and likely respond to) tissue forces during remodeling, thereby regulating the evolution of tissue structure according to mechanical requirements.

Evidence suggests that growth factors and hormones (autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine) are pivotal in orchestrating both synthesis and degradation of ECM components. Cytokines such as TGF-β, PDGF, and IL-1 clearly play an important role in the modulation of collagenase and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) expression. MMP enzymatic activities are regulated by TIMPs, which are especially important during wound repair. As natural inhibitors of the MMPs, TIMPS are multifunctional proteins with both MMP inhibitor activity and cell growth modulating properties. Degradation of the extracellular matrix is mediated by an excess of MMP activity over that of TIMPs. Distortion of the balance between matrix synthesis and turnover may result in altered matrix composition and amounts.

Cell–Cell and Cell–Matrix Interactions

Like cell–cell interactions, cell–matrix interactions have a high degree of specificity, requiring recognition, adhesion, electrical and chemical communication, cytoskeletal reorganization, and/or cell migration. Moreover, adhesion receptors may also act as transmembrane signaling molecules that transmit information about the environment to the inside of cells, in some cases all the way to the nucleus, and mediate the effects of signals initiated by growth factors or compounds controlling gene expression, phenotypic modulation and cell replication, differentiation and apoptosis (Figure II.1.5.3). Although many of the components of the extracellular matrix (ligands) with which cells interact are immobilized and not in solution (e.g., the integrin adhesion receptors and the vascular selectins (the latter modulate interaction of circulating inflammatory cells with the endothelium)), some soluble (secreted) factors also modulate cell–cell communication in the normal and pathologic regulation of tissue growth and maturation. Indeed, the array of specific binding of specialized cues with cell-surface receptors induces complex interactions that regulate tissue formation, homeostasis, and regeneration (Figure II.1.5.4). Moreover, the scaffolds used in tissue engineering applications often replicate the several functions of, and are intended to stimulate the production of, natural ECM (Lutolf et al., 2009).

FIGURE II.1.5.3 Integrin-ECM interaction. Schematic showing the mechanisms by which ECM (e.g., collagen, fibronectin, and laminin) and growth factors interact with cells, activate signaling pathways, and can influence gene expression, growth, motility, differentiation, and protein synthesis. Integrins bind ECM and interact with the cytoskeleton at focal adhesion complexes. This can initiate the production of intracellular messengers, or can directly mediate nuclear signals. Cell surface receptors for growth factors also initiate second signals. (Reproduced by permission from Kumar, V., Abbas, A. K., Fausto, N. & Aster, J. C. (eds.). (2010). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th Edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA.)

FIGURE II.1.5.4 Individual cell behavior and the dynamic state of multicellular tissues is regulated by reciprocal molecular interactions between cells and their surroundings. (Reproduced by permission from Lutolf, M. P. & Hubbell, J. A. (2005). Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nature Biotechnology, 23, 47–55.)

The integrins comprise a family of cell receptors with diverse specificity that bind ECM proteins, other cell surface proteins and plasma proteins, and control cell growth, differentiation, gene expression, and motility (Bokel and Brown, 2002). Some integrins bind only a single component of the ECM, e.g., fibronectin, collagen, or laminin (see above). Other integrins can interact with several of these polypeptides. In contrast to hormone receptors, which have high affinity and low abundance, the integrins exhibit low affinity and high abundance, so that they can bind weakly to several different but related matrix molecules. This property allows the integrins to promote cell–cell interactions as well as cell–matrix binding.

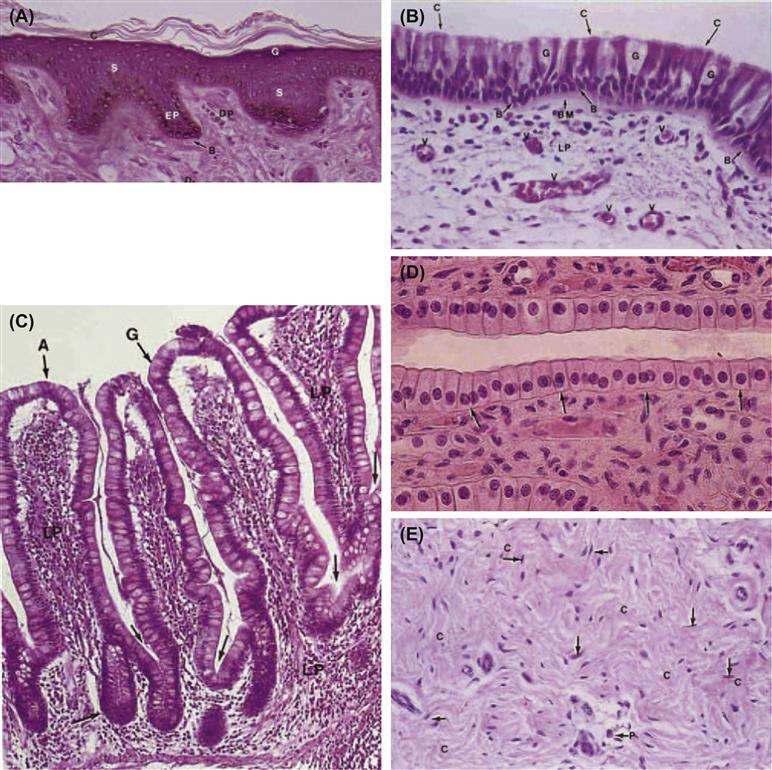

Basic Tissues

Humans have over a hundred distinctly different types of cells allocated to four types of basic tissues (Table II.1.5.1 and Figure II.1.5.5): (1) epithelium; (2) connective tissue; (3) muscle; and (4) nervous tissue. The different basic tissues have distinctive microscopic appearances that belie their specific functional roles. The basic tissues have their origins in embryological development; early events include the formation of a tube with three germ layers in its wall: (1) an outer layer of ectoderm (which gives rise to skin and the nervous system); (2) an inner layer of endoderm (from which the lining membranes of the gut, respiratory tract, and genitourinary system, and the liver and pancreas derive); and (3) a middle layer of mesoderm (which is the origin of muscle, bone, blood cells, and the blood forming organs and the heart).

TABLE II.1.5.1 The Basic Tissues: Classification and Examples

| Basic Tissues | Examples |

| Epithelial tissue | |

| Surface | Skin epidermis, gut mucosa |

| Glandular | Thyroid follicles, pancreatic acini |

| Special | Retinal or olfactory epithelium |

| Connective tissue | |

| Connective tissue proper | |

| Loose | Skin dermis |

| Dense (regular, irregular) | Pericardium, tendon |

| Special | Adipose tissue |

| Hemopoietic tissue, blood and lymph | Bone marrow, blood cells |

| Supportive tissue | Cartilage, bone |

| Muscle tissue | |

| Smooth | Arterial or gut smooth muscle |

| Skeletal | Limb musculature, diaphragm |

| Cardiac muscle | Heart |

| Nerve tissue | Brain cells, peripheral nerve |

FIGURE II.1.5.5 Photomicrographs of basic tissues, emphasizing key structural features. (A)–(D) Epithelium; (E), (F) connective tissue; (G) muscle; and (H) nervous tissue. (A) Skin. Note the thin stratum corneum (c) and stratum granulosum (g). Also shown are the stratum spinosum (s), stratum basale (b), epidermal pegs (ep), dermal papilla (dp), and dermis (d). (B) Trachea, showing goblet cells (g), ciliated columnar cells (c), and basal cells (b). Note the thick basement membrane (bm) and numerous blood vessels (v) in the lamina propria (lp). (C) Mucosa of the small intestine (ileum). Note the goblet (g) and columnar absorbing (a) cells, the lamina propria (lp), and crypts (arrows). (D) Epithelium of a kidney collecting duct resting on a thin basement membrane (arrows). (E) Dense irregular connective tissue. Note the wavy unorientated collagen bundles (c) and fibroblasts (arrows), (p), plasma cells. (F) Cancellous bone clearly illustrating the morphologic difference between inactive bone lining (endosteal, osteoprogenitor) cells (bl) and active osteoblasts (ob). The clear area between the osteoblasts and calcified bone represents unmineralized matrix or osteoid. (cl), Cement lines; (o), osteocycles. (G) Myocardium (cardiac muscle). The key features are centrally placed nuclei, intercalated discs (representing end-to-end junctions of adjoining cells) and the sarcomere structure visible as cross-striations in the cells. (H) Small nerve fascicles (n) with perineurium (p) separating it from two other fascicles (n). ((A)–(F) and (H) reproduced by permission from Berman, I. (1993). Color Atlas of Basic Histology, Appleton and Lange; (G) reproduced by permission from Schoen, F. J. (2004). The Heart. In: Cotran, R. S., Kumar, V. & Collins, T. (eds.). Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, 7th Edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA.)

Epithelia cover the internal and external body surfaces and accommodate diverse functions. An epithelial surface can be: (1) a protective dry, cutaneous membrane barrier (as in skin); (2) a moist, mucous membrane, lubricated by glandular secretions and variably absorptive (digestive and respiratory tracts); (3) a moist membrane lined by mesothelium, lubricated by fluid that derives from blood plasma (peritoneum, pleura, pericardium); (4) the inner lining of the circulatory system, called endothelium; and (5) the source of internal and external secretions (e.g., endocrine and sweat glands, respectively). Epithelium derives mostly from ectoderm and endoderm, but also from mesoderm.

Epithelial cells play fundamental roles in the directional movement of ions, water, and macromolecules between biological compartments, including absorption, secretion, and exchange. Therefore, the architectural and functional organization of epithelial cells includes structurally, biochemically, and physiologically distinct plasma membrane domains that contain region-specific ion channels, transport proteins, enzymes and lipids, and cell–cell junctional complexes. These components help integrate multiple cells to form an interface between biological compartments in organs. Subcellular epithelial specializations are not apparent to the naked eye – or even necessarily to light microscopy; they are best studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and by functional assays (e.g., assessing synthetic products, permeability, and transport).

Supporting the other tissues of the body, connective tissue arises from embryonic mesenchyme, a derivative of mesoderm. Connective tissue also serves as a scaffold and conduit, through which course the nerves and blood vessels that support the various epithelial tissues. Other types of tissue with varying functions are also of mesenchymal origin. These include dense connective tissue, adipose (fat) tissue, cartilage and bone, circulating cells (blood cells and their precursors in bone marrow), as well as inflammatory cells that defend the body against infectious organisms and other foreign agents.

Muscle cells develop from mesoderm and are highly specialized for contraction. They have the contractile proteins actin and myosin in varying amounts and configuration, depending on cell function. Muscle cells are of three types: smooth muscle; skeletal muscle; and cardiac muscle. The latter two have a striated microscopic appearance, owing to their discrete bundles of actin and myosin organized into sarcomeres. Smooth muscle cells, which have a less compact arrangement of myofilaments, are prevalent in the walls of blood vessels and the gastrointestinal tract. Their slow, non-voluntary contraction regulates blood vessel caliber, and proper movement of food and solid waste, respectively.

Nerve tissue, which derives from ectoderm, is highly specialized with respect to irritability and conduction. Nerve cells not only have cell membranes that generate electrical signals called action potentials, but also secrete neurotransmitters, molecules that trigger adjacent nerve or muscle cells to either transmit an impulse or to contract.

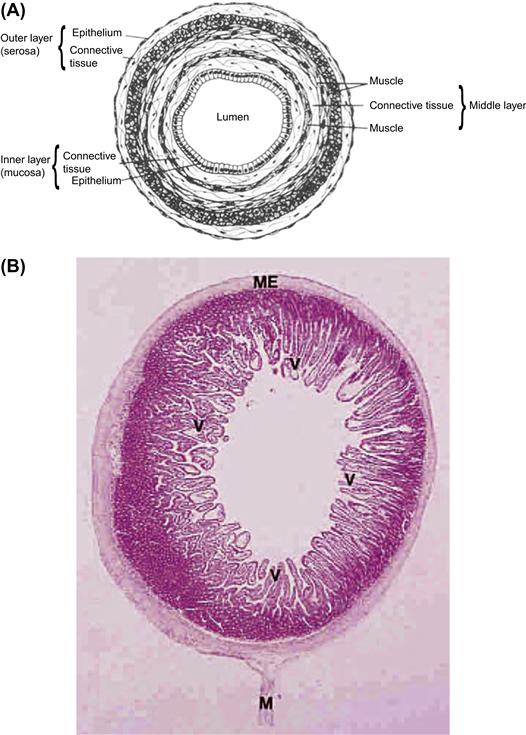

Organs

Several different types of tissues arranged into a functional unit constitute an organ. These have a composite structure in which epithelial cells typically perform the specialized work of the organ, while connective tissue and blood vessels support and provide nourishment to the epithelium. There are two basic organ patterns: tubular (or hollow) and compact (or solid) organs. Tubular organs include the blood vessels and the digestive, urogenital, and respiratory tracts; they have similar architectures in that each is composed of layers of tissue arranged in a specific sequence. For example, each has an inner coat consisting of a lining of epithelium, a middle coat consisting of layers of muscle (usually smooth muscle) and connective tissue, and an external coat consisting of connective tissue, often covered by epithelium (for example, the intestines or vascular walls) (Figure II.1.5.6). Specific variations in architecture reflect organ-specific functional requirements. While the outer coat of an organ that blends into surrounding structures is called the adventitia, the outside epithelial lining of an organ suspended in a body cavity (e.g., thoracic or abdominal) is called a serosa.

FIGURE II.1.5.6 General structure of a tubular organ system, as demonstrated by the gastrointestinal tract. (A) Organization of tissue layers in the digestive tract (e.g., stomach or intestines). (B) Photomicrograph of the dog jejunum illustrating villi (v), the muscularis external (me), and mesentery (M). In this organ the epithelium is organized into folds (the villi) in order to increase the surface area for absorption. ((A) Reproduced by permission from Borysenko, M. & Beringer, T. (1989). Functional Histology, 3rd Edn. Copyright 1989 Little, Brown, and Co.; (B) Reproduced by permission from Berman, I. (1993). Color Atlas of Basic Histology. Appleton and Lange.)

The histologic composition and organization, as well as the thickness, of these three layers of tubular systems varies characteristically with the physiologic functions performed by specific regions. The structure/function correlations are particularly well-demonstrated in the cardiovascular system (Figure II.1.5.7). Blood vessels have three layers: an intima (primarily endothelium); a media (primarily smooth muscle and elastin); and an adventitia (primarily collagen). The amounts and relative proportions of layers of the blood vessels are influenced by mechanical factors (especially blood pressure, which determines the amount and arrangement of muscular tissue), and metabolic factors (reflecting the local nutritional needs of the tissues). Three features will illustrate the variation in site-specific structure–function correlations:

• As discussed above, capillaries have a structural reduction of the vascular wall to only endothelium and minimal supporting structures to facilitate exchange (i.e., the metabolic function dominates). Thus, capillaries are part of the tissues they supply and, unlike larger vessels, do not appear as a separate anatomical unit.

• Arteries and veins have distinctive structures. The regional structural changes are primarily controlled by mechanical factors. The arterial wall is generally thicker than the venous wall, in order to withstand the higher blood pressures that prevail within arteries compared with veins. The thickness of the arterial wall gradually diminishes as the vessels themselves become smaller, but the wall–to–lumen ratio becomes greater in the periphery. Veins have a larger overall diameter, a larger lumen, and a narrower wall than the corresponding arteries with which they course.

• In essence, the heart is a blood vessel specialized for rhythmic contraction; its media is the myocardium, containing muscle cells (cardiac myocytes).

FIGURE II.1.5.7 Regional structural variations in the cardiovascular system. Although the basic organization is constant, the thickness and composition of the various layers differ, as a functional response to differential hemodynamic forces and tissue metabolic requirements. (Reproduced by permission from Mitchell, R. N. & Schoen, F. J. (2010). Blood Vessels. In: Kumar, V., Abbas, A. K., Fausto, N. & Aster, J. C. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th Edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA.)

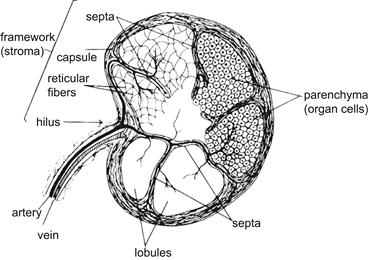

The blood supply of an organ comes from its outer aspect. In tubular organs, large vessels penetrate the outer coat, perpendicular to it, and give off branches that run parallel to the tissue layers (Figure II.1.5.8). These vessels divide yet again to give off penetrating branches that course through the muscular layer, and branch again in the connective tissue parallel to the layers. The small blood vessels have junctions (anastomoses) with one another in the connective tissue. These junctions may provide collateral pathways that can allow blood to bypass obstructions. Compact, solid organs have an extensive connective tissue framework, surrounded by a dense, connective tissue capsule (Figure II.1.5.9). Such organs have an area of thicker connective tissue where blood vessels and other conduits (e.g., airways in the lungs) enter the organ; this region is called the hilus. From the hilus, strands of connective tissue extend into the organ and may divide it into lobules.

FIGURE II.1.5.8 Vascularization of hollow organs. (Reproduced by permission from Borysenko, M. & Beringer, T. (1989). Functional Histology, 3rd Edn. Copyright, 1989 Little, Brown, and Co.)

FIGURE II.1.5.9 Organization of compact organs. (Reproduced by permission from Borysenko, M. & Beringer, T. (1989). Functional Histology, 3rd Edn. Copyright, 1989 Little, Brown, and Co.)

In both tubular and compact organs, the dominant cells comprising specialized tissues are the parenchyma (e.g., epithelial cells lining the gut, thyroglobulin-hormone producing epithelial cells in the thyroid or cardiac muscle cells in the heart). Parenchyma occurs in masses (e.g., endocrine glands), cords (e.g., liver), or tubules (e.g., kidney). Parenchymal cells can be arranged uniformly in an organ, or they may be segregated into a subcapsular region (cortex) and a deeper region (medulla), each performing a distinct functional role. The remainder of the organ has a delicate structural framework, including supporting cells, extracellular matrix, and vasculature (essentially the “service core”), which constitutes the stroma. After entering an organ, the blood supply branches repeatedly to small arteries, and ultimately capillaries in the parenchyma; veins and nerves generally follow the course of the arteries.

Parenchymal cells are generally more sensitive to chemical, physical, or ischemic (i.e., low blood flow) injury than stroma. Moreover, when an organ is injured, orderly repair and regrowth of parenchymal cells requires an intact underlying stroma.

Tissue Response to Injury: Inflammation, Repair, and Regeneration

A key protective response of an organism is its ability to eliminate damaged tissues and foreign invaders, such as microbes or exogenous non-biological materials (the latter including therapeutic biomaterials). Elimination of the intruder rids the organism of both the cause and the consequences of cell and tissue injury. Without this protective process, tissue wounds would not heal and infections would go unchecked. However, inappropriately triggered or uncontrolled inflammation can also be deleterious. Inflammation is usually a highly coordinated response involving proteins, leukocytes, and phagocytic cells (macrophages) that are derived from circulating cells, all of which travel in the blood and are recruited to a site where they are needed.

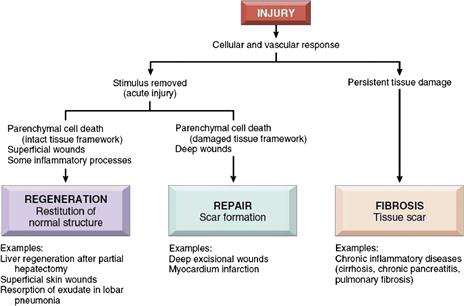

The outcome of tissue injury depends primarily on the tissue type affected, the extent of the injury, and whether it is persistent (Figure II.1.5.10). When an environmental perturbation or injury is transient or short-lived, tissue destruction is small, and the tissue is capable of homeostatic adjustment or regeneration; the outcome is restoration of normal structure and function. However, when tissue injury is extensive or occurs in tissues that do not regenerate, inflammation and repair occur, and the result is scarring (Singer and Clark, 1999). When an infection or foreign material cannot be eliminated, the body “controls” the foreign body or infection by creating a wall around it (and thereby isolating it as much as possible from healthy tissue). Thus, most inert biomaterials elicit an early inflammatory response, followed by a late tissue reaction characterized by encapsulation by a relatively thin fibrous tissue capsule (composed of collagen and fibroblasts, and similar to a scar). The nature of the reaction is largely dependent on the chemical and physical characteristics of the implant.

FIGURE II.1.5.10 Regeneration, repair, and fibrosis after injury and inflammation. (Reproduced by permission from Kumar, V., Abbas, A. K., Fausto, N. & Aster, J. C. (2010). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th Edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA.)

As described above, inflammation and repair follow cell and tissue injury induced by various exogenous and endogenous stimuli, both eliminating (i.e., diluting, destroying or isolating) the cause of the injury (e.g., microbes or toxins), and disposing of necrotic cells and tissues that occur as a result of the injury. In doing so, the inflammatory response initiates the process that heals and reconstitutes the tissue, by replacing the wound with native parenchymal cells or by filling up the defect with fibroblastic scar tissue, or some combination of both (such as skin reconstituting the epidermis and scarring the dermis) (Figure II.1.5.11). Inflammation and repair constitute an overlapping sequence of several processes (Figure II.1.5.12):

• Acute inflammation: The immediate and early response to injury, of relatively short duration, characterized by fluid and plasma protein exudation into the tissue, and by accumulation of neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes). In the case of an infection that cannot be easily eliminated, an abscess (i.e., a localized collection of acute inflammation and infectious organisms) is the outcome.

• Chronic inflammation: This phase is manifested histologically as lymphocytes and macrophages, often with concurrent tissue destruction, and can evolve into repair involving fibrosis and new blood vessel proliferation. A special type of chronic inflammation characterized by activated macrophages and often multinucleated giant cells, organized around an irritating focus, is called a granuloma or granulomatous inflammation. The pattern also occurs in pathologic states where the inciting agent is not removable, including the foreign body reaction (see below).

FIGURE II.1.5.11 Key concepts in tissue responses following injury. (A) Role of the extracellular matrix in regeneration versus repair, illustrated for liver injury. Regeneration requires an intact matrix and persistence of cells capable of proliferation. If both cells and matrix are damaged, repair occurs by fibrous tissue deposition and scar formation. (B) and (C) Wound healing and scar formation in skin. (B) Healing of a wound that caused little injury leads to a thin scar with minimal contraction. (C) Healing of a large wound causes substantial scar and more contraction and distortion of the tissue. (Reproduced by permission from Kumar, V., Abbas, A. K., Fausto, N. & Aster, J. C. (2010). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th Edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA.)

FIGURE II.1.5.12 Phases of cutaneous wound healing: Inflammation, proliferation, and maturation. (Reproduced by permission from Kumar, V., Abbas, A. K., Fausto, N. & Aster, J. C. (2010) Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th Edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA.)

Synthetic biomaterials are generally not immunogenic, and are therefore generally not “rejected” like a transplanted organ. However, they typically elicit the foreign body reaction (FBR), a special form of nonimmune inflammation. The most prominent cells in the FBR are macrophages, which presumably attempt to phagocytose the material, but degradation is difficult. Depending on the local milieu and the resultant chemical signals, microphages will differentiate (activate) in different ways, either pro-inflammatory or pro-healing and fibrosis (Mosser and Edwards, 2008; Brown et al, 2012). Multinucleated giant cells in the vicinity of a foreign body are generally considered evidence of a more severe FBR in which the material is particularly irritating. This reaction is frequently called a foreign body granuloma. The more “biocompatible” the implant, the more quiescent is the ultimate response.

• Scarring: In situations where repair cannot be accomplished by regeneration, scarring occurs as a composite of three sequential processes: (1) formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis); (2) deposition of collagen (fibrosis); and (3) maturation and remodeling of the scar (remodeling). The early healing tissue rich in new capillaries and proliferation of fibroblasts is called granulation tissue (not to be confused with granuloma, above). The essential features of the healing process are usually advanced by 4–6 weeks, although full scar remodeling may require much longer.

Inflammation is also associated with the release of chemical mediators from plasma, cells or extracellular matrix, which regulates the subsequent vascular and cellular events, and may modify their evolution. The chemical mediators of inflammation include the vasoactive amines (e.g., histamine), plasma proteases (of the coagulation, fibrinolytic, kinin, and complement systems), arachidonic acid metabolites (eicosinoids) produced in the cyclooxygenase pathway (the prostaglandins) and the lipoxygenase pathway (the leukotrienes), platelet-activating factor, cytokines (e.g., interleukin1 [IL-1], tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α] and interferon-γ [IFN-γ]), nitric oxide and oxygen-derived free radicals, and various intracellular constituents, particularly the lysosomal granules of inflammatory cells. Polypeptide growth factors also influence repair and healing by affecting cell growth, locomotion, contractility, and differentiation. Growth factors may act by endocrine (systemic), paracrine (stimulating adjacent cells) or autocrine (same cell carrying receptors for their own endogenously produced factors) mechanisms. Growth factors involved in mediating angiogenesis, fibroblast migration, proliferation, and collagen deposition in wounds include epidermal growth factor (EGF, important in proliferation of epithelial cells and fibroblasts), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF, involved in fibroblast and smooth muscle cell migration), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β, with a central role in fibrosis), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, with a central role in angiogenesis).

Techniques for Analysis of Cells and Tissues

Cells in culture (in vitro) often continue to perform many of the normal functions they have in the body (in vivo). Through measurement of changes in secreted products under different conditions, for example, culture methods can be used to study how cells respond to certain stimuli. However, since cells in culture do not have the usual chemical and physical environment that they have in tissues, normal physiological function may not always be present.

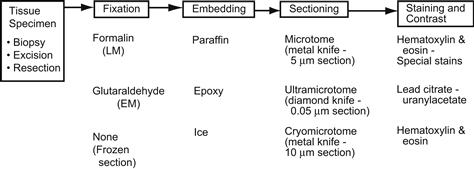

Techniques commonly used to study the structure of either normal or abnormal tissues, and the purpose of each mode of analysis, are summarized in Table II.1.5.2 and Figure II.1.5.13. The most widely used technique (historically and presently) for examining tissues is light microscopy, described below. Several advanced tissue analysis techniques are also increasingly being used to answer more detailed questions concerning cell and tissue function.

TABLE II.1.5.2 Techniques Used to Study Tissue

| Technique | Purpose |

| Gross examination | Determine overall specimen configuration; many diseases and processes can be diagnosed at this level |

| Light microscopy (LM) | Study overall microscopic tissue architecture and cellular structure |

| Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) | Study ultrastructure and identify cells and their and environment |

| Enzyme histochemistry | Demonstrate the presence and location of enzymes in gross or microscopic sections |

| Immunohistochemistry | Identify and locate specific molecules, usually proteins, for which a specific antibody is available as a probe |

| Microbiologic cultures | Diagnose the presence of infectious organisms |

| Morphometric studies (at gross, LM or TEM levels) | Quantitate the amounts, configuration, and distribution of specific structures |

| Chemical, biochemical and spectroscopic analysis | Assess bulk concentration of molecular or elemental constituents |

| Energy dispersive x-ray analysis (EDXA) | Perform site-specific elemental analysis in sections |

| In-situ hybridization | Identify presence and location of mRNA or DNA within cells and tissues in histological sections |

| Northern blot | Detect the presence, amount, and size of specific mRNA molecules |

| Western blot | Identify the presence and amount of specific proteins |

| Southern blot | Detect and identify specific DNA sequences |

| Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | Cyclical amplification of DNA to produce sufficient material for analysis |

| Tissue microarray | Permits study of multiple lesions simultaneously using tissue from multiple patients or blocks on the same slide; produced using a needle to biopsy conventional paraffin blocks and placing the cores into an array on a recipient paraffin block |

FIGURE II.1.5.13 Key features of tissue processing for examination by light and electron microscopy.

Light Microscopy

The conventional light microscopy technique involves obtaining the tissue sample, followed by fixation, paraffin embedding, sectioning, mounting on a glass slide, staining, and examination. Photographs of conventional tissue sections taken through a light microscope (photomicrographs) were illustrated in Figure II.1.5.5. Photographs of a tissue sample, paraffin block, and resulting tissue section on a glass slide are shown in Figure II.1.5.14. The tissue is obtained by either surgical excision (removal), biopsy (sampling) or autopsy (postmortem examination). A sharp instrument is used to dissect the tissue to avoid distortion from crushing. The key processing steps are summarized in the following paragraphs.

FIGURE II.1.5.14 Tissue processing steps for light microscopy. (A) Tissue section. (B) Paraffin block. (C) Resulting histologic section.

To preserve the structural relationships among cells, their environment, and subcellular structures in tissues, it is necessary to cross-link and preserve the tissue in a permanent, non-viable state called fixation. Specimens should be placed in fixatives as soon as possible after removal. Fixative solutions prevent degradation of the tissue when it is separated from its source of oxygen and nutrition (i.e., autolysis) by coagulating (i.e., cross-linking, denaturing, and precipitating) proteins. This prevents cellular hydrolytic enzymes (which are released when cells die) from degrading tissue components and spoiling tissues for microscopic analysis. Fixation also immobilizes fats and carbohydrates, reduces or eliminates enzymic and immunological reactivity, and kills microorganisms present in tissues.

A 37% solution of formaldehyde is called formalin; thus, 10% formalin is approximately 4% formaldehyde. This solution is the routine fixative in pathology for light microscopy. For TEM and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), glutaraldehyde preserves structural elements better than formalin. Adequate fixation in formalin and/or glutaraldehyde requires tissue samples less than 1.0 and 0.1 cm, respectively, in largest dimension. For adequate fixation, the volume of fixative into which a tissue sample is placed should generally be at least 5 to 10 times that of the tissue volume.

Dehydration and Embedding

In order to support the specimen during sectioning, specimen water (approximately 70% of tissue mass) must be replaced by paraffin wax or other embedding medium, such as glycolmethacrylate. This is done through several steps, beginning with dehydration of the specimen through increasing concentrations of ethanol (eventually to absolute ethanol). However, since alcohol is not miscible with paraffin (the final embedding medium), xylol (an organic solvent) is used as an intermediate solution.

Following dehydration, the specimen is soaked in molten paraffin and placed in a mold larger than the specimen, so that tissue spaces originally containing water, as well as a surrounding cube, are filled with wax. The mold is cooled, and the resultant solid block containing the specimen (see Figure II.1.5.14B) can then be easily handled.

Sectioning

Tissue specimens are sectioned on a microtome (which has a blade similar to a single-edged razor blade), that is progressively advanced through the specimen block. The shavings are picked up on glass slides. Sections for light microscopic analysis must be thin enough to both transmit light and avoid superimposition of various tissue components. Typically sections are approximately 5 μm thick – slightly thicker than a human hair, but thinner than the diameter of most cells. If thinner sections are required (e.g., approximately 0.06 μm thick ultrathin sections are necessary) for TEM analysis, a harder supporting (embedding) medium (usually epoxy plastic) and a correspondingly harder knife (usually diamond) are used. Sections for TEM analysis are cut on an ultramicrotome. Because the conventional paraffin technique requires overnight processing, frozen sections are often used to render an immediate diagnosis (e.g., during a surgical procedure that might be modified according to the diagnosis). In this method, the specimen itself is frozen, so that the solidified internal water acts as a support medium, and sections are then cut in a cryostat (i.e., a microtome in a cold chamber). Although frozen sections are extremely useful for immediate tissue examination, the quality of the appearance is inferior to that obtained by conventional fixation and embedding methods. Frozen sections may also be used to section specimens that contain a component of interest that would be dissolved out or otherwise altered by processing with the organic solvents required by paraffin embedding (e.g., some polymers).

Staining

Tissue components have no intrinsic contrast, and are of fairly uniform optical density. Therefore, in order for tissue to be visible by light microscopy, tissue elements must be distinguished by selective adsorption of dyes (Luna, 1968). Since most stains are aqueous solutions of dyes, staining requires the paraffin in the tissue section to be removed and replaced by water (rehydration). The stain used routinely in histology involves sequential incubation in the dyes hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Hematoxylin has an alkaline (basic) pH that stains blue–purple; substances stained with hematoxylin typically have a net negative charge and are said to be “basophilic” (e.g., cell nuclei containing DNA). In contrast, substances that stain with eosin, an acidic pigment that colors positively-charged tissue components pink–red, are said to be “acidophilic” or “eosinophilic” (e.g., cell cytoplasm, collagen). The tissue sections shown in Figure II.1.5.5 were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Special Staining and Immunohistochemistry

There are special staining methods for highlighting components that do not stain well with routine stains (e.g., microorganisms) or for indicating the chemical nature or the location of a specific tissue component (e.g., collagen, elastin; Table II.1.5.3). There are also special techniques for demonstrating the specific chemical activity of a compound in tissues (e.g., enzyme histochemistry). In this case, the specific substrate for the enzyme of interest is reacted with the tissue; a colored product precipitates in the tissue section at the site of the enzyme. In contrast, immunohistochemical staining takes advantage of the immunological properties (antigenicity) of a tissue component to demonstrate its nature and location by identifying sites of antibody binding. Antibodies to the particular tissue constituent are attached to a dye, usually a compound activated by a peroxidase enzyme, and reacted with a tissue section (immunoperoxidase technique) or the antibody is attached to a compound that is excited by a specific wavelength of light (immunofluorescence). Although some antigens and enzymatic activity can survive the conventional histological processing technique, both enzyme activity and immunological reactivity are often largely eliminated by routine fixation and embedding. Therefore, histochemistry and immunohistochemistry are frequently done on frozen sections. Nevertheless special preservation and embedding techniques now available often allow immunological methods to be carried out on carefully fixed tissue.

TABLE II.1.5.3 Stains for Light Microscopic Histologya

| To Demonstrate | Stain |

| Overall morphology | Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) |

| Collagen | Masson’s trichrome |

| Elastin | Verhoeff-van Gieson |

| Glycosoaminoglycans (GAGs) | Alcian blue |

| Collagen–elastic–GAGs | Movat |

| Bacteria | Gram |

| Fungi | Methenamine silver or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) |

| Iron | Prussian blue |

| Calcium phosphates (or calcium) | von Kossa (or alizarin red) |

| Fibrin | Lendrum or phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH) |

| Amyloid | Congo red |

| Inflammatory cell types | Esterases (e.g., chloroacetate esterase for neutrophils, nonspecific esterase for macrophages) |

aReproduced by permission from F. J. Schoen, Interventional and Surgical Cardiovascular Pathology: Clinical Correlations and Basic Principles, Saunders, 1989.

Electron Microscopy

Contrast in the electron microscope depends on relative electron densities of tissue components. Sections are stained with salts of heavy metals (osmium, lead, and uranium), which react differentially with different structures, creating patterns of electron density that reflect tissue and cellular architecture. An example of an electron photomicrograph is shown in Figure II.1.5.1B.

It is often possible to derive quantitative information from routine tissue sections using various manual or computer-aided methods. Morphometric or stereologic methodology, as these techniques are called, can be extremely useful in providing an objective basis for otherwise subjective measurements (Loud and Anversa, 1984). Techniques for sampling information from small amounts of tissue include laser microdissection, confocal microscopy, two-photon microscopy, etc.

Three-Dimensional Interpretation

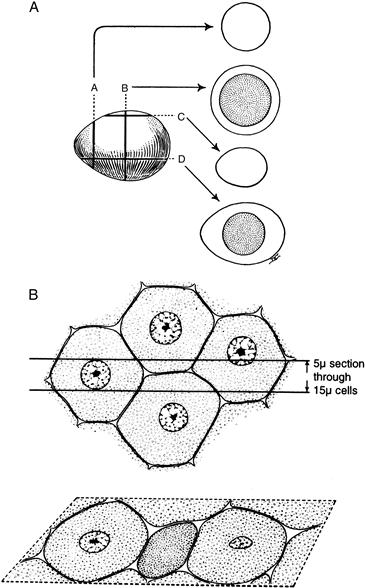

Interpretation of tissue sections depends on the reconstruction of three-dimensional information from two-dimensional observations on tissue sections that are usually thinner than a single cell. Therefore, a single section may yield an unrepresentative view of the whole. A particular structure (even a very simple one) can look very different, depending on the plane of section. Figure II.1.5.15 shows how multiple sections must be examined to appreciate the actual configuration of an object or a collection of cells.

FIGURE II.1.5.15 Considerations for three-dimensional interpretation of two-dimensional information. Sections through a subject in different levels and orientations can give different impressions about its structure, here illustrated (A) for a hard-boiled egg, and (B) for a section through cells of a uniform size that suggests that the cells are heterogenous. (Modified by permission from Cormack, D. H. (1993). Essential Histology. Copyright 1993, Lippincott.)

Artifacts

Artifacts are unwanted or confusing features in tissue sections that result from errors or technical difficulties in obtaining, processing, sectioning or staining the specimen. Recognition of artifacts avoids misinterpretation. The most frequent and important artifacts are autolysis, tissue shrinkage, separation of adjacent structures, precipitates formed by poor buffering or by degradation of fixatives or stains, folds or wrinkles in the tissue sections, knife nicks or rough handling (e.g., crushing) of the specimen.

Identification, Genotyping, and Functional Assessment of Cells, Including Synthetic Products, in Cells or Tissue Sections

It is frequently necessary to accurately ascertain or verify the identity of a cell, or to determine some aspect of its function, including the production of synthetic molecules. For such an assay, either isolated cells or whole tissues are used, depending on the objective of the study. Isolated cells or minced tissue have the advantage of allowing molecular and/or biochemical analyses on the cells and/or products, and often allow the acquisition of quantitative data. Nevertheless, the major advantage of whole tissue preparations is the ability to spatially localize molecules of interest in the context of architectural features of the tissue. Methods for identification and determination of the function of cells and identification of extracellular components in situ are summarized in Table II.1.5.4. New techniques are available. Cellular apoptosis and proliferation can be quantified (Watanabe et al., 2002). Immunohistochemical markers allow detection of proteins that are highly expressed in a tissue section. However, the relevant antibodies to proteins expressed in high concentration must be available, and the expense of such studies limits their usefulness. In-situ hybridization permits similar investigation of gene expression but, as with immunohistochemistry, only a discrete panel of previously predicted genes can be probed.

Table II.1.5.4 Determination of Cell Function, Gene Expression, and Synthetic Products

Special histologic stains

Electron microscopy

Histochemistry/cytochemistry

Autoradiography

Antibody methods for light microscopy

Immunofluorescence Immunoperoxidase

Immuno-electron microscopy

Flow cytometry

Molecular methods

In-situ hybridization

In-situ polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

TUNEL staining (for apoptosis)

Gene expression profiling (with or without laser capture microdissection)

Molecular imaging

Confocal microscopy

Advanced Tissue and Cell Analysis

Several very exciting new and evolving techniques are available to assay the anatomy and function of tissues and cells with extraordinary precision and/or spatial localization. These can be used individually or coupled. Very exciting are various forms of functional genomic and proteomic analyses (Chen et al., 2009). In particular, gene expression profiling shows the complete array of genes expressed in cells or tissues; the technology may identify pathogenetically distinct subtypes of any lesion and search for fundamental mechanisms even when candidate genes are unknown (Duggal et al., 2009). Confocal microscopy helps localize a particular component in a living cell by observing a series of optical sections (planes) which are reconstructed into a three-dimensional image (Watson et al., 2000; Howell et al., 2002). Tissue microassays permit the comparative examination of potentially hundreds of individual specimens in a single paraffin block (Hewitt, 2012). In addition, laser-assisted microdissection techniques permit isolation of an individual or a homogenous population of cells on selected cell populations under direct visualization from a routine histological section of complex, heterogeneous tissue (Edwards, 2007; Kurkalli et al., 2010). Very exciting new imaging technologies may permit analysis of viable tissues in vivo (Pinaud et al., 2006; Georgakoudi et al., 2008; Weissleder and Pittet, 2008).

Regenerative Capacity of Cells and Tissues

Organs are theoretically capable of renewing via three routes: (1) proliferation and differentiation of resident stem cells; (2) dedifferentiation of resident cells followed by proliferation/differentiation; and (3) homing and differentiation of circulating stem cells. Most types of cell populations can undergo turnover, but the process is highly regulated, and the production of cells of a particular kind generally ceases until some are damaged or another need arises. Rates of proliferation are different among various cell populations, and are frequently divided into three categories: (1) renewing (also called labile) cells have continuous turnover, with proliferation balancing cell loss that accrues by death or physiological depletion; (2) expanding (also called stable) cells, normally having a low rate of death and replication, retain the capacity to divide following stimulation; and (3) static (also called permanent) cells, not only have no normal proliferation, but they have also lost their capacity to divide. The relative proliferative (and regenerative) capacity of various cell types is summarized in Table II.1.5.5.

TABLE II.1.5.5 Regenerative Capacity of Cells Following Injury

In normally renewing (labile) cell populations (e.g., skin, intestinal epithelium, bone marrow), tissue-specific (often called “adult”) stem cells proliferate to form daughter cells that can become differentiated and repopulate the damaged cells. A particular stem cell produces many such daughter cells, and, in some cases, several different kinds of cells can arise from a common multipotential ancestor cell (also called multipotency, e.g., bone marrow stem cells lead to several different types of blood cells). In epithelia (such as the epidermis layer of skin), the stem cells reside at the base of the tissue layer, away from the surface; differentiation and maturation occur as the cells move toward the surface. Regenerative tissues, especially those with high proliferative capacity, such as the hematopoietic system (e.g., bone marrow) and the epithelia of the skin and the gastrointestinal tract, renew themselves continually and can regenerate following injury, providing that the stem cells of these tissues have not been destroyed. Expanding (stable) populations can increase their rate of replication in response to suitable stimuli. Stable cell populations include glandular epithelial cells, liver, fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, osteoblasts, and endothelial cells. Cells that die are generally replaced by new ones of the same kind. In contrast, permanent (static) cells have minimal, if any, normal mitotic capacity and, in general, cannot be induced to regenerate. Following injury, they are replaced by scar. The inability to regenerate large, functional amounts of certain tissue types following injury can result in a clinically important deficit, since the function of the damaged tissue is irretrievably lost. For example, an area of heart muscle or brain which is damaged by ischemic injury (e.g., myocardial infarction) cannot be effectively replaced by viable cells; the necrotic area is repaired by scar has no functional potential. Therefore, in heart the remainder of the heart muscle must assume the workload of the lost tissue. In brain, the majority of function is lost in the cells damaged by a stroke.

While the classical concepts enumerated above continue to hold true from a practical standpoint, recent evidence suggests that some regeneration of neural tissue and heart muscle cells can occur under certain circumstances following injury. Both the extent to which this can occur and effective strategies to harness this potential and exciting source of new tissue are as yet unknown (Orive et al., 2009; Hosoda et al., 2010; Yi et al., 2010).

Cell/Tissue–Biomaterials Interactions

For most applications, biomaterials are in contact with cells and tissues (either hard tissue, including bone; soft tissue, including cardiovascular tissues; and blood in the case of cardiovascular implants or extracorporeal devices), often for prolonged periods. Thus, rational and sophisticated use of biomaterials and design of medical devices requires some knowledge of the general concepts concerning the interaction of cells with non-physiological surfaces. This discussion complements that described in Chapter II.1.2. and II.1.3.

Most tissue-derived cells require attachment to a solid surface for viability, growth, migration, and differentiation. The nature of that attachment is an important regulator of those functions. Moreover, the behavior and function of adherent cells (e.g., shape, proliferation, synthetic function) depend on the characteristics of the substrate, particularly its adhesiveness and mechanical properties (Reilly & Engler, 2010).

Following contact with tissue or blood, a bare surface of a biomaterial is covered rapidly (usually in seconds) with proteins that are adsorbed from the surrounding body fluids. The chemistry of the underlying substrate (particularly as it affects wettability and surface charge) controls the nature of the adherent protein layer. For example, macrophage fusion and platelet adhesion/aggregation are strongly dependent on surface chemistry. Moreover, although cells are able to adhere, spread, and grow on bare biomaterial surfaces in vitro, proteins absorbed from the adjacent tissue environment or blood and/or secreted by the adherent cells themselves markedly enhance cell attachment, migration, and growth.

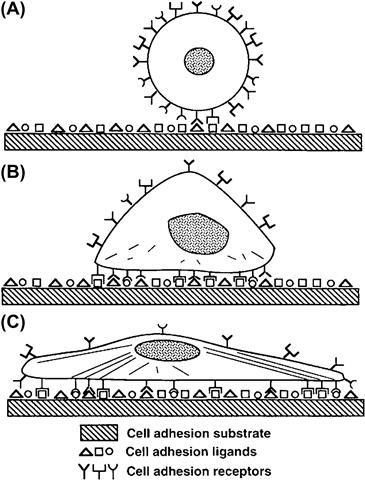

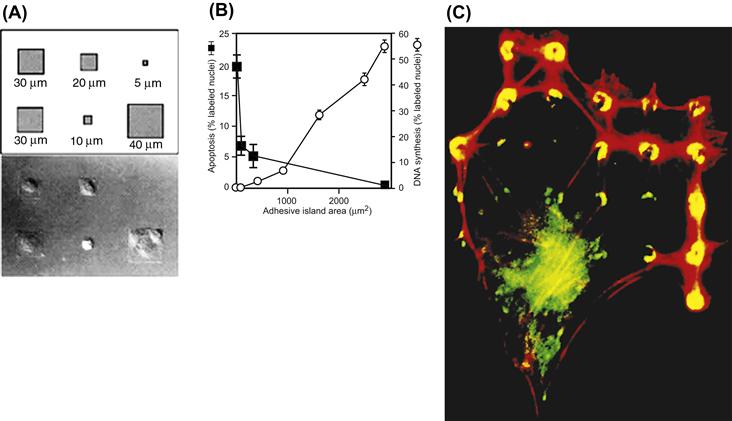

Cell adhesion to biomaterials and the ECM is mediated by cytoskeletally-associated receptors in the cell membrane, which interact with cell adhesion proteins that adsorb to the material surface from the surrounding plasma and other fluids (Figure II.1.5.16). Cell adhesion triggers multiple functional biochemical signaling pathways within the cell (Chen, 2008). The interactions are critical to cell-growth control responsive to mechanical forces mediated through associated changes in cell shape and cytoskeletal tension (Ingber, 2010b). Focal adhesions are considered to represent the strongest such interactions. They comprise a complex assembly of intra- and extracellular proteins, coupled to each other through transmembrane integrins. Cell-surface integrin receptors promote cell attachment to substrates, and especially those covered with the extracellular proteins fibronectin and vibronectin. These receptors transduce biochemical signals to the nucleus by activating the same intracellular signaling pathways that are used by soluble growth factor receptors. The more cells spread, the higher their rate of proliferation. The importance of cell spreading on their proliferation has been emphasized by classical experiments that used endothelial cells cultured on microfabricated substrates containing fibronectin-coated islands of various defined shapes and sizes of a micrometer scale (Figure II.1.5.17) (Chen et al., 1997). Cells spread to the limits of the islands containing a fibronectin substrate; cells on circular islands were circular while cells on square islands became square in shape and had 90° corners. When the spreading of the cells was restricted by small adhesive islands (10–30 μm), proliferation was arrested, while larger islands (80 μm) permitted proliferation. When the cells were grown on micropatterned substrates with 3–5 μm dots, comprising multiple adhesive islands that permitted the cells to extend over multiple islands while maintaining the total ECM contact similar to that of one small island (that was associated with inhibited growth), they proliferated. This confirmed that the ability of cells to proliferate depended directly on the degree to which the cells were allowed to distend physically, and not on the actual surface area of substrate binding. Thus, cell distortion is a critical determinant of cell behavior.

FIGURE II.1.5.16 Progression of anchorage-dependent cell adhesion. (A) Initial contact of cell with solid substrate. (B) Formation of bonds between cell surface receptors and cell adhesion ligands. (C) Cytoskeletal reorganization with progressive spreading of the cell on the substrate for increased attachment strength. (Reproduced by permission from Massia, S. P. (1999). Cell–Extracellular Matrix Interactions Relevant to Vascular Tissue Engineering. In: Tissue Engineering of Prosthetic Vascular Grafts, Zilla, P. & Greisler, H. P. (eds.). RG Landes Co., 1999.)

FIGURE II.1.5.17 Effect of spreading on cell growth and apoptosis. (A) Schematic diagram showing the initial pattern design containing different-sized square adhesive islands and Nomarski views of the final shapes of bovine adrenal capillary endothelial cells adherent to the fabricated substrate. Distances indicate lengths of the square’s sides. (B) Apoptotic index (percentage of cells exhibiting positive TUNEL staining) and DNA synthesis index (percentage of nuclei labeled with 5-bromodeoxyuridine) after 24 hours, plotted as a function of the projected cell area. Data were obtained only from islands that contained single adherent cells; similar results were obtained with circular or square islands, and with human or bovine endothelial cells. (C) Fluorescence micrograph of an endothelial cell spread over a substrate containing a regular array of small (5 μm diameter) circular ECM islands separated by nonadhesive regions created with a microcontact printing technique. Yellow rings and crescents indicate colocalization of vinculin (green) and F-actin (red) within focal adhesions that form only on the regulatory spaced circular ECM islands. ((A), (B) Reproduced by permission from Chen, C. S. et al. (1997) Geometric control of cell life and death. Science, 276, 1425; (C) Reproduced by permission from Ingber, D. E. (2003). Mechanosensation through integrins: Cells act locally but think globally. Proc Natl Acad. Sci., 100, 1472.)

Interactions of cells with ECM differ from those with soluble regulatory factors owing to the reciprocal interactions between the ECM and the cell’s actin cytoskeleton (Ingber, 2010b). For example, rigid substrates promote cell spreading and growth in the presence of soluble mitogens; in contrast, flexible scaffolds that cannot resist cytoskeletal forces promote cell retraction, inhibit growth, and promote differentiation. Thus, the properties of the nature and configuration of the surface-bound ECM on a substrate, and the properties of the substrate itself, can regulate cell–biomaterials interactions. The key concept is that a biomaterial surface can contain specific chemical and structural information that controls tissue formation, in a manner analogous to cell–cell communication and patterning during embryological development.

The exciting potential of this strategy is exemplified by tissue engineering approaches that employ biomaterials with surfaces designed to stimulate biophysical and biochemical microenviromental use of highly precise spatial and temporal reactions with proteins and cells at the molecular level, to trigger cell fate decisions such as adhesion, proliferation, migration, and specific gene-expression profiles and differentiation patterns (Lutolf et al, 2009). Such materials provide the scientific foundation for molecular design of scaffolds that could be seeded with cells in vitro for subsequent implantation or specifically attract endogenous functional cells in vivo. A key challenge in tissue engineering is to understand quantitatively how cells respond to various molecular signals and integrate multiple inputs to generate a given response, and to control non-specific interactions between cells and a biomaterial, so that cell responses specifically follow desired receptor–ligand interactions. Understanding the principles regulating these responses, the means to chart them, and the ability to fabricate elaborate interfaces with carefully controlled ligand type, density, clustering, and spatial distribution (potentially in three dimensions) will ultimately permit novel biosensors, smart biomaterials, advanced medical devices, microarrays, and tissue regenerative approaches.

Bibliography

1. Berman I. Color Atlas of Basic Histology. Appleton and Lanse 1993.

2. Bokel C, Brown NH. Integrins in development: Moving on, responding to, and sticking to the extracellular matrix. Develop Cell. 2002;3:311–321.

3. Borysenko M,, & Bringer T, et al. Functional Histology. 3rd ed. Little, Brown, and Co 1989.

4. Bozsenko M, Beringer. T. Functional Histology. 3rd ed. Little Brown and co 1989.

5. Brown BN, Ratner BD, Goodman sB, Amar S, Badylak SF. Macrophage polarization: An opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3792–3802.

6. Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nature Med. 2003;9:653–660.

7. Chen CS. Mechanotransduction: A field pulling together?. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3285–3292.

8. Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides G, Ingber DE. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 1997;276:1425–1428.

9. Chen X, Jorgenson E, Cheung ST. New tools for functional genomic analysis. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:754–760.