Chapter II.2.2

Inflammation, Wound Healing, and the Foreign-Body Response

Inflammation, wound healing, and foreign-body reaction are generally considered as parts of the tissue or cellular host responses to injury. Table II.2.2.1 lists the sequence/continuum of these events following injury. Overlap and simultaneous occurrence of these events should be considered; e.g., the foreign-body reaction at the implant interface may be initiated with the onset of acute and chronic inflammation. From a biomaterials perspective, placing a biomaterial in the in vivo environment requires injection, insertion or surgical implantation, all of which injure the tissues or organs involved.

Biocompatibility and Implantation

Implantation of a biomaterial, medical device, or prosthesis results in tissue injury that initiates host defense systems, e.g., inflammatory, wound healing, and foreign-body responses. The extent and time-dependent nature of these responses, in the context of the characteristics and properties of the biomaterial, form the basis for determining the biocompatibility or safety of the biomaterial. In addition to defining the biocompatibility of a biomaterial, a fundamental understanding of these responses permits their use as biological design criteria.

TABLE II.2.2.1 Sequence/Continuum of Host Reactions Following Implantation of Medical Devices

Injury

Blood–material interactions

Provisional matrix formation

Acute inflammation

Chronic inflammation

Granulation tissue

Foreign-body reaction

Fibrosis/fibrous capsule development

The placement procedure initiates a response to injury by the tissue, organ or body, and mechanisms are activated to maintain homeostasis. The degrees to which the homeostatic mechanisms are perturbed, and the extent to which pathophysiologic conditions are created and undergo resolution, are a measure of the host reactions to the biomaterial and may ultimately determine its biocompatibility. Although it is convenient to separate homeostatic mechanisms into blood–material or tissue–material interactions, it must be remembered that the various components or mechanisms involved in homeostasis are present in both blood and tissue, and are a part of the physiologic continuum. Furthermore, it must be noted that host reactions may be tissue-dependent, organ-dependent, and species-dependent. Obviously, the extent of injury varies with the implantation procedure.

Overview

Inflammation is generally defined as the reaction of vascularized living tissue to local injury. Inflammation serves to contain, neutralize, dilute, or wall off the injurious agent or process. In addition, it sets in motion a series of events that may heal and reconstitute the implant site through replacement of the injured tissue by regeneration of native parenchymal cells, formation of fibroblastic scar tissue, or a combination of these two processes.

Immediately following injury, there are changes in vascular flow, caliber, and permeability. Fluid, proteins, and blood cells escape from the vascular system into the injured tissue in a process called exudation. Following changes in the vascular system, which also include changes induced in blood and its components, cellular events occur and characterize the inflammatory response. The effect of the injury and/or biomaterial in situ on plasma or cells can produce chemical factors that mediate many of the vascular and cellular responses of inflammation.

Blood–material interactions and the inflammatory response are intimately linked, and in fact early responses to injury involve mainly blood and vasculature. Regardless of the tissue or organ into which a biomaterial is implanted, the initial inflammatory response is activated by injury to vascularized connective tissue (Table II.2.2.2). Since blood and its components are involved in the initial inflammatory responses, blood clot formation and/or thrombosis also occur. Blood coagulation and thrombosis are generally considered humoral responses that may be influenced by other homeostatic mechanisms, such as the extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation systems, the complement system, the fibrinolytic system, the kinin-generating system, and platelets. Thrombus or blood clot formation on the surface of a biomaterial is related to the well-known Vroman effect (see Chapter II.3.2), in which a hierarchical and dynamic series of collision, absorption, and exchange processes, determined by protein mobility and concentration, regulate early time-dependent changes in blood protein adsorption. From a wound-healing perspective, blood protein deposition on a biomaterial surface is described as provisional matrix formation. Blood interactions with biomaterials are generally considered under the category of hematocompatibility and are discussed elsewhere in this book.

TABLE II.2.2.2 Cells and Components of Vascularized Connective Tissue

Intravascular (Blood) Cells

Erythrocytes (RBC)

Neutrophils (PMNs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes)

Monocytes

Eosinophils

Lymphocytes

Plasma cells

Basophils

Platelets

Connective Tissue Cells

Mast cells

Fibroblasts

Macrophages

Lymphocytes

Extracellular Matrix Components

Collagens

Elastin

Proteoglycans

Fibronectin

Laminin

Injury to vascularized tissue in the implantation procedure leads to immediate development of the provisional matrix at the implant site. This provisional matrix consists of fibrin, produced by activation of the coagulation and thrombosis systems, and inflammatory products released by the complement system, activated platelets, inflammatory cells, and endothelial cells. These events occur early, within minutes to hours following implantation of a medical device. Components within or released from the provisional matrix, i.e., fibrin network (thrombosis or clot), initiate the resolution, reorganization, and repair processes such as inflammatory cell and fibroblast recruitment. The provisional matrix appears to provide both structural and biochemical components to the process of wound healing. The complex three-dimensional structure of the fibrin network with attached adhesive proteins provides a substrate for cell adhesion and migration. The presence of mitogens, chemoattractants, cytokines, and growth factors within the provisional matrix provides for a rich milieu of activating and inhibiting substances for various cellular proliferative and synthetic processes. The provisional matrix may be viewed as a naturally derived, biodegradable, sustained release system in which mitogens, chemoattractants, cytokines, and growth factors are released to control subsequent wound-healing processes. In spite of the increase in our knowledge of the provisional matrix and its capabilities, our knowledge of the control of the formation of the provisional matrix and its effect on subsequent wound healing events is poor. In part, this lack of knowledge is due to the fact that much of our knowledge regarding the provisional matrix has been derived from in vitro studies, and there is a paucity of in vivo studies that provide for a more complex perspective. Little is known regarding the provisional matrix which forms at biomaterial and medical device interfaces in vivo, although attractive hypotheses have been presented regarding the presumed ability of materials and protein adsorbed materials to modulate cellular interactions through their interactions with adhesive molecules and cells.

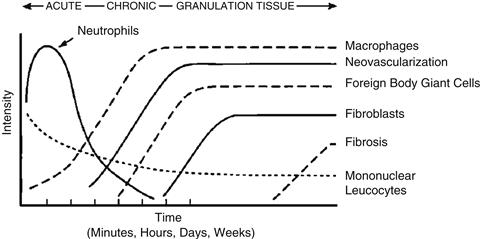

The predominant cell type present in the inflammatory response varies with the age of the inflammatory injury (Figure II.2.2.1). In general, neutrophils predominate during the first several days following injury and then are replaced by monocytes as the predominant cell type. Three factors account for this change in cell type: neutrophils are short lived and disintegrate and disappear after 24–48 hours; neutrophil emigration from the vasculature to the tissues is of short duration; and chemotactic factors for neutrophil migration are activated early in the inflammatory response. Following emigration from the vasculature, monocytes differentiate into macrophages and these cells are very long-lived (up to months). Monocyte emigration may continue for days to weeks, depending on the injury and implanted biomaterial, and chemotactic factors for monocytes are activated over longer periods of time. In short-term (24 hour) implants in humans, administration of both H1 and H2 histamine receptor antagonists greatly reduced the recruitment of macrophages/monocytes and neutrophils on polyethylene terephthalate surfaces. These studies also demonstrated that plasma-coated implants accumulated significantly more phagocytes than did serum-coated implants.

FIGURE II.2.2.1 The temporal variation in the acute inflammatory response, chronic inflammatory response, granulation tissue development, and foreign-body reaction to implanted biomaterials. The intensity and time variables are dependent upon the extent of injury created in the implantation and the size, shape, topography, and chemical and physical properties of the biomaterial.

The temporal sequence of events following implantation of a biomaterial is illustrated in Figure II.2.2.1. The size, shape, and chemical and physical properties of the biomaterial may be responsible for variations in the intensity and duration of the inflammatory or wound-healing process. Thus, intensity and/or time duration of the inflammatory reaction may characterize the biocompatibility of a biomaterial.

While injury initiates the inflammatory response, the chemicals released from plasma, cells or injured tissue mediate the inflammatory response. Important classes of chemical mediators of inflammation are presented in Table II.2.2.3. Several points must be noted in order to understand the inflammatory response and how it relates to biomaterials. First, although chemical mediators are classified on a structural or functional basis, different mediator systems interact and provide a system of checks and balances regarding their respective activities and functions. Second, chemical mediators are quickly inactivated or destroyed, suggesting that their action is predominantly local (i.e., at the implant site). Third, generally the lysosomal proteases and the oxygen-derived free radicals produce the most significant damage or injury. These chemical mediators are also important in the degradation of biomaterials.

TABLE II.2.2.3 Important Chemical Mediators of Inflammation Derived from Plasma, Cells or Injured Tissue

Acute Inflammation

Acute inflammation is of relatively short duration, lasting for minutes to hours to days, depending on the extent of injury. Its main characteristics are the exudation of fluid and plasma proteins (edema) and the emigration of leukocytes (predominantly neutrophils). Neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes, PMNs) and other motile white cells emigrate or move from the blood vessels to the perivascular tissues and the injury (implant) site. Leukocyte emigration is assisted by “adhesion molecules” present on leukocyte and endothelial surfaces. The surface expression of these adhesion molecules can be induced, enhanced or altered by inflammatory agents and chemical mediators. White cell emigration is controlled, in part, by chemotaxis, which is the unidirectional migration of cells along a chemical gradient. A wide variety of exogenous and endogenous substances have been identified as chemotactic agents. Specific receptors for chemotactic agents on the cell membranes of leukocytes are important in the emigration or movement of leukocytes. These and other receptors also play a role in the transmigration of white cells across the endothelial lining of vessels, and the activation of leukocytes. Following localization of leukocytes at the injury (implant) site, phagocytosis and the release of enzymes occur following activation of neutrophils and macrophages. The major role of the neutrophil in acute inflammation is to phagocytose microorganisms and foreign materials. Phagocytosis is seen as a three-step process in which the injurious agent undergoes recognition and neutrophil attachment, engulfment, and killing or degradation. In regard to biomaterials, engulfment and degradation may or may not occur, depending on the properties of the biomaterial.

Although biomaterials are not generally phagocytosed by neutrophils or macrophages because of the disparity in size (i.e., the surface of the biomaterial is greater than the size of the cell), certain events in phagocytosis may occur. The process of recognition and attachment is expedited when the injurious agent is coated by naturally occurring serum factors called “opsonins.” The two major opsonins are immunoglobulin G (IgG) and the complement-activated fragment, C3b. Both of these plasma-derived proteins are known to adsorb to biomaterials, and neutrophils and macrophages have corresponding cell-membrane receptors for these opsonization proteins. These receptors may also play a role in the activation of the attached neutrophil or macrophage. Other blood proteins such as fibrinogen, fibronectin, and vitronectin may also facilitate cell adhesion to biomaterial surfaces. Owing to the disparity in size between the biomaterial surface and the attached cell, frustrated phagocytosis may occur. This process does not involve engulfment of the biomaterial, but does cause the extracellular release of leukocyte products in an attempt to degrade the biomaterial.

Henson (1971) has shown that neutrophils adherent to complement-coated and immunoglobulin-coated nonphagocytosable surfaces may release enzymes by direct extrusion or exocytosis from the cell. The amount of enzyme released during this process depends on the size of the polymer particle, with larger particles inducing greater amounts of enzyme release. This suggests that the specific mode of cell activation in the inflammatory response in tissue depends upon the size of the implant, and that a material in a phagocytosable form (i.e., powder, particulate or nanomaterial) may provoke a different degree of inflammatory response than the same material in a nonphagocytosable form (i.e., film). In general, materials greater than 5 microns are not phagocytosed, while materials less than 5 microns, i.e., nanomaterials, can be phagocytosed by inflammatory cells.

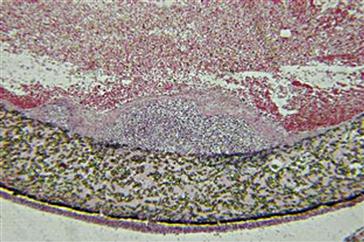

Acute inflammation normally resolves quickly, usually less than 1 week, depending on the extent of injury at the implant site. However, the presence of acute inflammation (i.e., PMNs) at the tissue/implant interface at time periods beyond 1 week (i.e., weeks, months, or years) suggests the presence of an infection (Figure II.2.2.2).

FIGURE II.2.2.2 Acute inflammation, secondary to infection, of an ePTFE (expanded poly tetrafluoroethylene) vascular graft. A focal zone of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is present at the lumenal surface of the vascular graft, surrounded by a fibrin cap, on the blood-contacting surface of the ePTFE vascular graft. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification 4 ×.

Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is less uniform histologically than acute inflammation. In general, chronic inflammation is characterized by the presence of macrophages, monocytes, and lymphocytes, with the proliferation of blood vessels and connective tissue. Many factors can modify the course and histologic appearance of chronic inflammation.

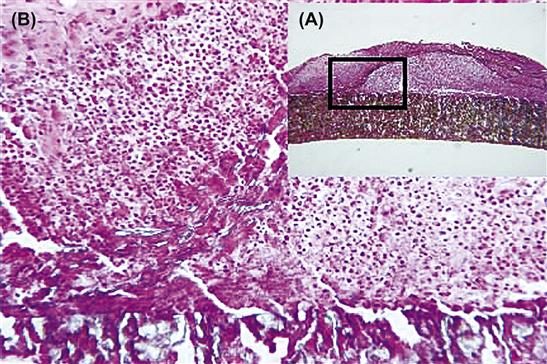

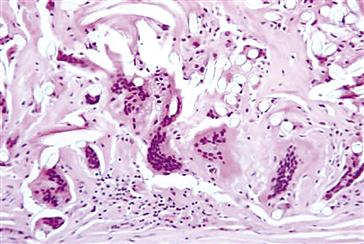

Persistent inflammatory stimuli lead to chronic inflammation. While the chemical and physical properties of the biomaterial in themselves may lead to chronic inflammation, motion in the implant site by the biomaterial or infection may also produce chronic inflammation. The chronic inflammatory response to biomaterials is usually of short duration, and is confined to the implant site. The presence of mononuclear cells, including lymphocytes and plasma cells, is considered chronic inflammation, whereas the foreign-body reaction with the development of granulation tissue is considered the normal wound healing response to implanted biomaterials (i.e., the normal foreign-body reaction). Chronic inflammation with the presence of collections of lymphocytes and monocytes at extended implant times (weeks, months, years) may also suggest the presence of a long-standing infection (Figures II.2.2.3A and II.2.2.3B). The prolonged presence of acute and/or chronic inflammation also may be due to toxic leachables from a biomaterial.

FIGURE II.2.2.3 Chronic inflammation, secondary to infection, of an ePTFE arteriovenous shunt for renal dialysis. (A) Low-magnification view of a focal zone of chronic inflammation. (B) High-magnification view of the outer surface with the presence of monocytes and lymphocytes at an area where the outer PTFE wrap had peeled away from the vascular graft. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification (A) 4 ×, (B) 20 ×.

Lymphocytes and plasma cells are involved principally in immune reactions, and are key mediators of antibody production and delayed hypersensitivity responses. Although they may be present in nonimmunologic injuries and inflammation, their roles in such circumstances are largely unknown. Little is known regarding humoral immune responses and cell-mediated immunity to synthetic biomaterials. The role of macrophages must be considered in the possible development of immune responses to synthetic biomaterials. Macrophages and dendritic cells process and present the antigen to immunocompetent cells, and thus are key mediators in the development of immune reactions.

Monocytes and macrophages belong to the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), also known as the reticuloendothelial system (RES). These systems consist of cells in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and specialized tissues. Table II.2.2.4 lists the tissues that contain cells belonging to the MPS or RES. The specialized cells in these tissues may be responsible for systemic effects in organs or tissues secondary to the release of components or products from implants through various tissue–material interactions (e.g., corrosion products, wear debris, degradation products) or the presence of implants (e.g., microcapsule or nanoparticle drug-delivery systems).

TABLE II.2.2.4 Tissues and Cells of MPS and RES

| Tissues | Cells |

| Implant sites | Inflammatory macrophages |

| Liver | Kupffer cells |

| Lung | Alveolar macrophages |

| Connective tissue | Histiocytes |

| Bone marrow | Macrophages |

| Spleen and lymph nodes | Fixed and free macrophages |

| Serous cavities | Pleural and peritoneal macrophages |

| Nervous system | Microglial cells |

| Bone | Osteoclasts |

| Skin | Langerhans cells |

| Lymphoid tissue | Dendritic cells |

The macrophage is probably the most important cell in chronic inflammation, because of the great number of biologically active products it can produce. Important classes of products produced and secreted by macrophages include neutral proteases, chemotactic factors, arachidonic acid metabolites, reactive oxygen metabolites, complement components, coagulation factors, growth-promoting factors, and cytokines.

Growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), TGF-α/epidermal growth factor (EGF), and interleukin-1 (IL-1) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) are important to the growth of fibroblasts and blood vessels, and the regeneration of epithelial cells. Growth factors released by activated cells can stimulate production of a wide variety of cells; initiate cell migration, differentiation, and tissue remodeling; and may be involved in various stages of wound healing.

Granulation Tissue

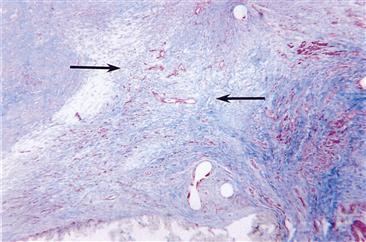

Within one day following implantation of a biomaterial (i.e., injury), the healing response is initiated by the action of monocytes and macrophages. Fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells in the implant site proliferate and begin to form granulation tissue, which is the specialized type of tissue that is the hallmark of healing inflammation. Granulation tissue derives its name from the pink, soft granular appearance on the surface of healing wounds, and its characteristic histologic features include the proliferation of new small blood vessels and fibroblasts (Figure II.2.2.4). Depending on the extent of injury, granulation tissue may be seen as early as 3–5 days following implantation of a biomaterial.

FIGURE II.2.2.4 Granulation tissue in the anastomotic hyperplasia at the anastomosis of an ePTFE vascular graft. Capillary development (red slits) and fibroblast infiltration with collagen deposition (blue) from the artery form the granulation tissue (arrows). Masson’s Trichrome stain. Original magnification 4 ×.

The new small blood vessels are formed by budding or sprouting of pre-existing vessels in a process known as neovascularization or angiogenesis. This process involves proliferation, maturation, and organization of endothelial cells into capillary vessels. Fibroblasts also proliferate in developing granulation tissue, and are active in synthesizing collagen and proteoglycans. In the early stages of granulation tissue development, proteoglycans predominate but later collagen, especially type III collagen, predominates and forms the fibrous capsule. Some fibroblasts in developing granulation tissue may have the features of smooth muscle cells, i.e., actin microfilaments. These cells are called myofibroblasts, and are considered to be responsible for the wound contraction seen during the development of granulation tissue. Macrophages are almost always present in granulation tissue. Other cells may also be present if chemotactic stimuli are generated.

The wound-healing response is generally dependent on the extent or degree of injury or defect created by the implantation procedure. Wound healing by primary union or first intention is the healing of clean, surgical incisions in which the wound edges have been approximated by surgical sutures. Healing under these conditions occurs without significant bacterial contamination, and with a minimal loss of tissue. Wound healing by secondary union or second intention occurs when there is a large tissue defect that must be filled or there is extensive loss of cells and tissue. In wound healing by secondary intention, regeneration of parenchymal cells cannot completely reconstitute the original architecture, and much larger amounts of granulation tissue are formed that result in larger areas of fibrosis or scar formation. Under these conditions, different regions of tissue may show different stages of the wound-healing process simultaneously.

Granulation tissue is distinctly different from granulomas, which are small collections of modified macrophages called epithelioid cells. Langhans’ or foreign-body-type giant cells may surround nonphagocytosable particulate materials in granulomas. Foreign-body giant cells (FBGCs) are formed by the fusion of monocytes and macrophages in an attempt to phagocytose the material (Figure II.2.2.5).

FIGURE II.2.2.5 In vivo transition from blood-borne monocyte to biomaterial adherent monocyte/macrophage to foreign-body giant cell at the tissue–biomaterial interface. Little is known regarding the indicated biological responses, which are considered to play important roles in the transition to FBGC development.

Foreign-Body Reaction

The foreign-body reaction to biomaterials is composed of foreign-body giant cells and the components of granulation tissue (e.g., macrophages, fibroblasts, and capillaries in varying amounts), depending upon the form and topography of the implanted material (Figure II.2.2.6). Relatively flat and smooth surfaces such as those found on breast prostheses have a foreign-body reaction that is composed of a layer of macrophages one-to-two cells in thickness. Relatively rough surfaces such as those found on the outer surfaces of expanded poly tetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) or Dacron vascular prostheses have a foreign-body reaction composed of macrophages and foreign-body giant cells at the surface. Fabric materials generally have a surface response composed of macrophages and foreign-body giant cells, with varying degrees of granulation tissue subjacent to the surface response (Figure II.2.2.7).

FIGURE II.2.2.6 (A) Focal foreign-body reaction to polyethylene wear particulate from a total knee prosthesis. Macrophages and foreign-body giant cells are identified within the tissue and lining the apparent void spaces indicative of polyethylene particulate. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification 20 ×. (B) Partial polarized light view. Polyethylene particulate is identified within the void spaces commonly seen under normal light microscopy. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification 20 ×.

FIGURE II.2.2.7 Foreign-body reaction with multinucleated foreign body giant cells and macrophages at the periadventitial (outer) surface of a Dacron vascular graft. Fibers from the Dacron vascular graft are identified as clear oval voids. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification 20 ×.

As previously discussed, the form and topography of the surface of the biomaterial determine the composition of the foreign-body reaction. With biocompatible materials, the composition of the foreign-body reaction in the implant site may be controlled by the surface properties of the biomaterial, the form of the implant, and the relationship between the surface area of the biomaterial and the volume of the implant. For example, high surface-to-volume implants, such as fabrics, porous materials, particulate or microspheres will have higher ratios of macrophages and foreign-body giant cells in the implant site than smooth-surface implants, which will have fibrosis as a significant component of the implant site.

The foreign-body reaction consisting mainly of macrophages and/or foreign-body giant cells may persist at the tissue–implant interface for the lifetime of the implant (Figure II.2.2.1). Generally, fibrosis (i.e., fibrous encapsulation) surrounds the biomaterial or implant with its interfacial foreign-body reaction, isolating the implant and foreign-body reaction from the local tissue environment. Early in the inflammatory and wound-healing response, the macrophages are activated upon adherence to the material surface.

Although it is generally considered that the chemical and physical properties of the biomaterial are responsible for macrophage activation, the subsequent events regarding the activity of macrophages at the surface are not clear. Tissue macrophages, derived from circulating blood monocytes, may coalesce to form multinucleated foreign-body giant cells. It is not uncommon to see very large foreign-body giant cells containing large numbers of nuclei on the surface of biomaterials. While these foreign-body giant cells may persist for the lifetime of the implant, it is not known if they remain activated, releasing their lysosomal constituents, or become quiescent.

Figure II.2.2.5 demonstrates the progression from circulating blood monocyte, to tissue macrophage, to foreign-body giant cell development that is most commonly observed. Indicated in the figure are important biological responses that are considered to play an important role in FBGC development. Material surface chemistry may control adherent macrophage apoptosis (i.e., programmed cell death) (see Chapter II.3.3) that renders potentially harmful macrophages nonfunctional, while the surrounding environment of the implant remains unaffected. The level of adherent macrophage apoptosis appears to be inversely related to the surface’s ability to promote fusion of macrophages into FBGCs, suggesting a mechanism for macrophages to escape apoptosis.

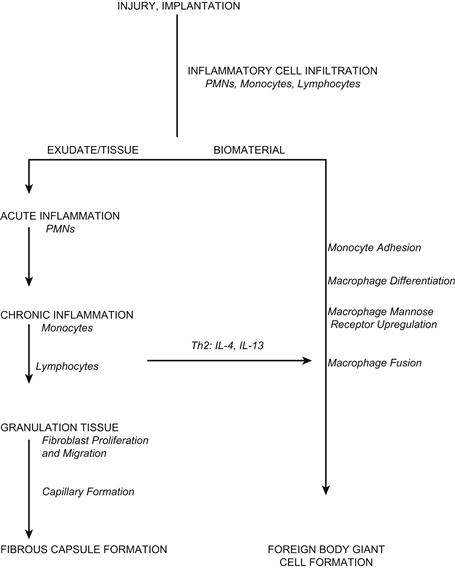

Figure II.2.2.8 demonstrates the sequence of events involved in inflammation and wound healing when medical devices are implanted. In general, the PMN predominant acute inflammatory response and the lymphocyte/monocyte predominant chronic inflammatory response resolve quickly (i.e., within 2 weeks) depending on the type and location of the implant. Studies using IL-4 or IL-13, respectively, demonstrate the role for Th2 helper lymphocytes and/or mast cells in the development of the foreign-body reaction at the tissue/material interface. Integrin receptors of IL-4-induced FBGC are characterized by the early constitutive expression of αVβ1, and the later induced expression of α5β1 and αXβ2, which indicate potential interactions with adsorbed complement C3, fibrin(ogen), fibronectin, Factor X, and vitronectin. Interactions through indirect (paracrine) cytokine and chemokine signaling have shown a significant effect in enhancing adherent macrophage/FBGC activation at early times, whereas interactions via direct (juxtacrine) cell–cell mechanisms dominate at later times. Th2 helper lymphocytes have been described as “anti-inflammatory” based on their cytokine profile, of which IL-4 is a significant component.

FIGURE II.2.2.8 Sequence of events involved in inflammatory and wound-healing responses leading to foreign-body giant cell formation.

Fibrosis/Fibrous Encapsulation

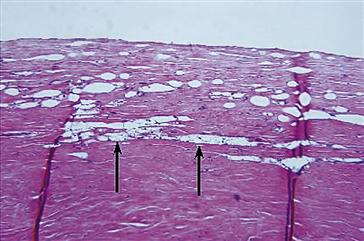

The end-stage healing response to biomaterials is generally fibrosis or fibrous encapsulation (Figure II.2.2.9). However, there may be exceptions to this general statement (e.g., porous materials inoculated with parenchymal cells or porous materials implanted into bone) (Figure II.2.2.10). As previously stated, the tissue response to implants is, in part, dependent upon the extent of injury or defect created in the implantation procedure and the amount of provisional matrix.

Injury and Repair at Implant Sites

The ultimate goal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine is replacement of injured tissue by cells that reconstitute normal tissue and organ structures. Numerous approaches, including stem cells, scaffolds, growth factors, etc., are currently being investigated. However, the relatively rapid responses of inflammation, wound healing, and the foreign-body reaction, as well as other significant factors in tissue regeneration, present major challenges to the successful achievement of this goal.

FIGURE II.2.2.9 Fibrous capsule composed of dense, compacted collagen. This fibrous capsule had formed around a Mediport catheter reservoir. Loose connective tissue with small arteries, veins, and a nerve is identified below the acellular fibrous capsule.

FIGURE II.2.2.10 Fibrous capsule with a focal foreign-body reaction to silicone gel from a silicone gel–filled silicone-rubber breast prosthesis. The breast prosthesis–tissue interface is at the top of the photomicrograph. Oval void spaces lined by macrophages and a few giant cells are identified and a focal area of foamy macrophages (arrows) indicating macrophage phagocytosis of silicone gel is identified. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification 10 ×.

Repair of implant sites can involve two distinct processes: regeneration, which is the replacement of injured tissue by parenchymal cells of the same type or replacement by connective tissue that constitutes the fibrous capsule. These processes are generally controlled by either: (1) the proliferative capacity of the cells in the tissue or organ receiving the implant and the extent of injury as it relates to the destruction; or (2) persistence of the tissue framework of the implant site. See Chapter II.3.4 for a more complete discussion of the types of cells present in the organ parenchyma and stroma, respectively.

The regenerative capacity of cells allows them to be classified into three groups: labile; stable (or expanding); and permanent (or static) cells (see Chapter II.3.3). Labile cells continue to proliferate throughout life; stable cells retain this capacity but do not normally replicate; and permanent cells cannot reproduce themselves after birth. Perfect repair with restitution of normal structure can theoretically occur only in tissues consisting of stable and labile cells, whereas all injuries to tissues composed of permanent cells may give rise to fibrosis and fibrous capsule formation with very little restitution of the normal tissue or organ structure. Tissues composed of permanent cells (e.g., nerve cells and cardiac muscle cells) most commonly undergo an organization of the inflammatory exudate, leading to fibrosis. Tissues of stable cells (e.g., parenchymal cells of the liver, kidney, and pancreas); mesenchymal cells (e.g., fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, osteoblasts, and chondroblasts); and vascular endothelial and labile cells (e.g., epithelial cells, lymphoid and hematopoietic cells) may also follow this pathway to fibrosis or may undergo resolution of the inflammatory exudate, leading to restitution of the normal tissue structure.

The condition of the underlying framework or supporting stroma of the parenchymal cells following an injury plays an important role in the restoration of normal tissue structure. Retention of the framework with injury may lead to restitution of the normal tissue structure, whereas destruction of the framework most commonly leads to fibrosis. It is important to consider the species-dependent nature of the regenerative capacity of cells. For example, cells from the same organ or tissue, but from different species, may exhibit different regenerative capacities and/or connective tissue repair.

Following injury, cells may undergo adaptations of growth and differentiation. Important cellular adaptations are atrophy (decrease in cell size or function), hypertrophy (increase in cell size), hyperplasia (increase in cell number), and metaplasia (change in cell type). Other adaptations include a change by cells from producing one family of proteins to another (phenotypic change) or marked overproduction of protein. This may be the case in cells producing various types of collagens and extracellular matrix proteins in chronic inflammation and fibrosis. Causes of atrophy may include decreased workload (e.g., stress-shielding by implants), diminished blood supply, and inadequate nutrition (e.g., fibrous capsules surrounding implants).

Local and systemic factors may play a role in the wound-healing response to biomaterials or implants. Local factors include the site (tissue or organ) of implantation, the adequacy of blood supply, and the potential for infection. Systemic factors may include nutrition, hematologic derangements, glucocortical steroids, and pre-existing diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and infection.

Finally, the implantation of biomaterials or medical devices may be best viewed at present from the perspective that the implant provides an impediment or hindrance to appropriate tissue or organ regeneration and healing. Given our current inability to control the sequence of events following injury in the implantation procedure, restitution of normal tissue structures with function is rare. Current studies directed toward developing a better understanding of the modification of the inflammatory response, stimuli providing for appropriate proliferation of permanent and stable cells, and the appropriate application of growth factors may provide keys to the control of inflammation, wound healing, and fibrous encapsulation of biomaterials.

Case Study Implant Toxicity

In vivo implantation studies were carried out subcutaneously in rats and rabbits with naltrexone sustained release preparations that included placebo (polymer only) beads and naltrexone containing beads. Histopathological tissue reactions utilizing standard procedures and light microscopic evaluation to the respective preparations were determined at days 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28. The only significant histological finding in both rats and rabbits at any time period was the inflammation that occurred focally around the naltrexone containing beads. The focal inflammatory cell density in both rats and rabbits was higher for the naltrexone beads than for the placebo beads at days 14, 21, and 28, respectively. This difference in inflammatory response between naltrexone beads and placebo beads increased with increasing time of implantation. Considering the resolution of the inflammatory response for the placebo beads with implantation time in both rats and rabbits, it is suggested that the naltrexone drug itself is identified as the causative agent of the focal inflammation present surrounding the naltrexone beads in the implant sites (Yamaguchi & Anderson, 1992).

The important lesson from this case study is the necessary use of appropriate control materials. If no negative control, i.e., placebo polymer-only material, had been used, the polymer in the naltrexone containing beads also would have been considered as a causative agent of the extended inflammatory response. Similar inflammatory responses have been identified with drugs, polymer plasticizers and other additives, fabrication and manufacturing aids, and sterilization residuals. Each case presents its own unique factors in a risk assessment process necessary for determining safety (biocompatibility) and benefit versus risk in clinical application.

Bibliography

1. Anderson JM. Biological responses to materials. Ann Rev Mater Res. 2001;31:81–110.

2. Anderson JM, Jones JA. Phenotypic dichotomies in the foreign-body reaction. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5114–5120.

3. Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign-body reaction to biomaterials. Seminars in Immunology. 2008;20:86–100.

4. Brodbeck WG, Anderson JM. Giant cell formation and function. Curr Opin In Hematology. 2009;16:53–57.

5. Browder T, Folkman J, Pirie-Shepherd S. The hemostatic system as a regulator of angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1521–1524.

6. Broughton G, Janis JE, Attinger CE. The basic science of wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117 12S–34S.

7. Chang DT, Colton E, Anderson JM. Paracrine and juxtacrine lymphocyte enhancement of adherent macrophage and foreign-body giant cell activation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2009;89A(2):490–498.

8. Clark RAF, ed. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing; 1996.

9. Gallin JI, Snyderman R, eds. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1999.

10. Henson PM. The immunologic release of constituents from neutrophil leukocytes: II Mechanisms of release during phagocytosis, and adherence to nonphagocytosable surfaces. J Immunol. 1971;107:1547.

11. Hunt TK, Heppenstall RB, Pines E, Rovee D, eds. Soft and Hard Tissue Repair. New York, NY: Praeger Scientific; 1984.

12. Hynes RO. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687.

13. Hynes RO, Zhao Q. The evolution of cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:F89–F96.

14. Jones JA, Chang DT, Meyerson H, Colton E, Kwon IK, et al. Proteomic analysis and quantification of cytokines and chemokines from biomaterial surface-adherent macrophages and foreign-body giant cells. J Biomed Mater Res. 2007;83A:585–596.

15. Jones KS. Assays on the influence of biomaterial on allogeneic rejection in tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering: Part B. 2008a;14(4):407–417.

16. Jones KS. Effects of biomaterial-induced inflammation on fibrosis and rejection. Seminars in Immunology. 2008b;20:130–136.

17. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2005.

18. Marchant RE, Anderson JM, Dillingham EO. In vivo biocompatibility studies VII Inflammatory response to polyethylene and to a cytotoxic polyvinylchloride. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986;20:37–50.

19. McNally AK, Anderson JM. Interleukin-4 induces foreign-body giant cells from human monocytes/macrophages Differential lymphokine regulation of macrophage fusion leads to morphological variants of multinucleated giant cells. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1487–1499.

20. McNally AK, MacEwan SR, Anderson JM. Alpha subunit partners to Beta1 and Beta2 integrins during IL-4-induced foreign-body giant cell formation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2007;82A:568–574.

21. McNally AK, Jones JA, MacEwan SR, Colton E, Anderson JM. Vitronectin is a critical protein adhesion substrate for IL-4-induced foreign-body giant cell formation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2008;86A(2):535–543.

22. Nel A, Xia T, Mädler L, Li N. Toxic potential of materials at the nano level. Science. 2006;311:622–627.

23. Nguyen LL, D’Amore PA. Cellular interactions in vascular growth and differentiation. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;204:1–48.

24. Pierce GF. Inflammation in nonhealing diabetic wounds: The space–time continuum does matter. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(2):399–403.

25. Sefton MV, Babensee JE, Woodhouse KA, eds. Special issue on innate and adaptive immune responses in tissue engineering. Seminars in Immunology. 2008; 20(2).

26. Yamaguchi K, Anderson JM. Biocompatibility studies of naltrexone sustained release formulations. J Controlled Rel. 1992;19:299–314.

27. Zdolsek J, Eaton JW, Tang L. Histamine release and fibrinogen adsorption mediate acute inflammatory responses to biomaterial implants in humans. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2007;5:31–37.