Chapter II.2.7

Tumors Associated with Biomaterials and Implants

Biomaterials have been shown to be potentially tumorigenic in laboratory animals, and malignancies have occurred rarely in association with metallic and other implants in pets and humans. Thus, the possibility that implant materials could cause tumors or promote tumor growth has long been a concern of clinicians and biomaterials researchers. This chapter describes general concepts in neoplasia (i.e., the process of tumor formation), the association of tumors with implants in humans and animals, the pathobiology of tumor formation adjacent to (and potentially stimulated by) biomaterials, and other pathophysiologic interactions of biomaterials with tissues that may simulate tumor formation.

General Concepts

Neoplasia, which literally means “new growth,” is the process of excessive and uncontrolled cell proliferation (Kumar et al., 2010). The new growth is called a neoplasm or tumor (i.e., a swelling, since most neoplasms are expansile, solid masses of abnormal tissue). Tumors are either benign (when their pathologic characteristics and clinical behavior are relatively innocent) or malignant (meaning harmful, often deadly). Malignant tumors are collectively referred to as cancers (derived from the Latin word for crab, to emphasize their obstinate ability to adhere to adjacent structures and spread in many directions simultaneously). The characteristics of benign and malignant tumors are summarized in Table. II.2.7.1. Types of malignant tumors are shown in Figure. II.2.7.1. Benign tumors do not penetrate (invade) adjacent tissues, nor do they spread to distant sites. They remain localized and, thus, surgical excision can be curative in many cases. In contrast, malignant tumors have a propensity to invade contiguous tissues. Moreover, owing to their ability to gain entrance into blood and lymph vessels, cells from a malignant neoplasm can be transported to distant sites, where subpopulations of malignant cells take up residence, grow, and again invade as satellite tumors (called metastases).

TABLE II.2.7.1 Characteristics of Benign and Malignant Tumors

| Characteristics | Benign | Malignant |

| Differentiation | Well defined; structure may be typical of tissue of origin | Less differentiated, with bizarre (anaplastic) cells; often atypical structure |

| Rate of growth | Usually progressive and slow; may come to a standstill or regress; cells in mitosis are rare | Erratic, and may be slow to rapid; mitoses may be absent to numerous and abnormal |

| Local invasion | Usually cohesive, expansile, well-demarcated masses that neither invade nor infiltrate the surrounding normal tissues | Locally invasive, infiltrating adjacent normal tissues |

| Metastasis | Absent | Often present at distant sites; larger and more undifferentiated primary tumors more likely to metastasize |

FIGURE II.2.7.1 Types of malignant tumors. (A) Carcinoma, exemplified by an adenocarcinoma (gland formation noted by asterisk). (B) Sarcoma (composed of spindle cells). (C) Lymphoma (composed of an aggregation of malignant lymphocytes). All stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

(A, B and C courtesy of Robert F. Padera, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA.)

The primary descriptor of any tumor is its cell or tissue of origin. Benign tumors are identified by the suffix “oma,” which is preceded by a reference to the cell or tissue of origin (e.g., adenoma – from an endocrine gland; chondroma – from cartilage). The malignant counterparts of benign tumors carry similar names, except that the suffix carcinoma is applied to cancers derived from epithelium (e.g., squamous- or adeno-carcinoma, from protective and glandular epithelia, respectively), and sarcoma (e.g., osteo- or chondro-sarcoma, producing bone and cartilage, respectively) is applied to those of mesenchymal (i.e., connective tissue or vascular) origin. Malignant neoplasms of the hematopoietic (i.e., blood cell producing) system, in which the cancerous cells circulate in blood, are called leukemias; solid tumors of lymphoid tissue are called lymphomas.

Cancer cells express varying degrees of resemblance to the normal precursor cells from which they derive. Thus, neoplastic growth entails both abnormal cellular proliferation, and modification of the structural and functional characteristics of the cell types involved. Malignant cells are generally less differentiated than their original normal counterparts. The structural similarity of cancer cells to those of the tissue of origin enables specific diagnosis (of both source organ and cell type); moreover, the degree of resemblance to the corresponding normal tissue usually predicts prognosis of the patient (i.e., expected outcome based on biologic behavior of the cancer surmised from its pathologic characteristics). Therefore, poorly differentiated tumors are generally more aggressive (i.e., display more malignant behavior) than those that are better differentiated. The degree to which a tumor mimics a normal cell or tissue type is called its grade of differentiation. The extent of spread and other effects on the patient determine its stage.

Neoplastic growth is unregulated. Neoplastic cell proliferation is therefore unrelated to the physiological requirements of the tissue, and is unaffected by removal of the stimulus which initially caused it. Thus, its growth is autonomous. These characteristics differentiate neoplasms from: (1) normal proliferations of cells during fetal development or postnatal growth; (2) normal wound healing following an injury; and (3) hyperplastic growth which adapts to a physiological need, but which ceases when the stimulus is removed.

Analogous to normal tissues (see Chapter II.1.5), benign and malignant tumors have two basic components: (1) proliferating neoplastic cells that constitute their parenchyma; and (2) supportive stroma made up of connective tissue and blood vessels. The parenchyma of neoplasms is characteristic of the specific cells of origin. Tumor growth and evolution are critically dependent on the non-specific stroma, which is usually composed of blood vessels, connective tissue, and inflammatory cells.

Neoplasms occurring at the site of implanted medical devices are rare, despite the large numbers of implants used clinically over an extended period of time. Nevertheless, both human and veterinary implant-associated tumors have been reported, most as case reports or small series.

Association of Implants with Human and Animal Tumors

Neoplasms occurring at the site of implanted medical devices are rare, despite the large numbers of implants used clinically over an extended period of time. Nevertheless, both human and veterinary implant-associated tumors have been reported, most as case reports or small series (Pedley et al., 1981; Schoen, 1987; Black, 1988; Jennings et al., 1988; Keel et al., 2001; Visuri et al., 2006a,b; Balzer and Weiss, 2009). In all, approximately 100 cases of tumors associated with orthopedic and other surgical implants have been reported, and tumors related to other foreign materials (e.g., bullets, shrapnel, other metal fragments, sutures, bone wax, and surgical sponge) are also known. One review cites 46 cases of reported malignant tumors at the site of total hip arthroplasty from 1974 to 2002 (Visuri et al., 2006a). Tumors are also well-known to occur with environmental exposure and consequent pulmonary ingestion of foreign materials, especially asbestos, which has a cause-and-effect relationship with a special type of tumor called mesothelioma (Robinson et al., 2005).

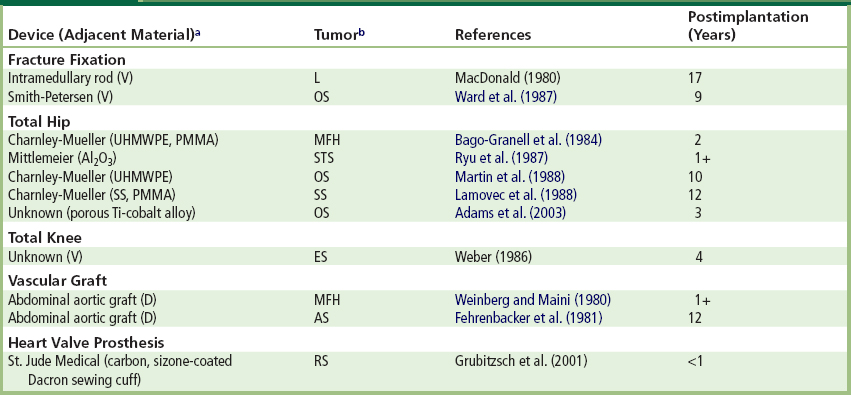

The vast majority of malignant neoplasms associated with clinical fracture fixation devices, total joint replacements, vascular grafts, breast implants, and experimental foreign-bodies in both animals and humans are sarcomas (i.e., mesenchymal tumors). They comprise various histologic subtypes, including fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma), chondrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, angiosarcoma, etc., and are characterized by rapid and locally infiltrative growth. Therapeutic implant-related tumors have been reported both short- and long-term following implantation. In a more recent case series and review confined to orthopedic implant sarcomas (Keel et al., 2001), most presented less than 15 years following surgery; implant associated tumors presented as early as 0.5 years and as late as 30 years. An osteosarcoma has been reported forming adjacent to a clinical titanium total hip replacement for osteoarthritis three years following insertion in a 68-year-old man (illustrated in Figure. II.2.7.2) (Keel et al., 2001). Diagnosis was delayed, since the initial symptoms of the tumor were attributed to the original orthopedic problem. Carcinomas, reported in association with foreign-bodies far less frequently, have usually been restricted to situations where an implant has been placed in the lumen of an epithelium-lined organ. Illustrative reported cases are noted in Table. II.2.7.2; descriptions of others are available (Jennings, et al., 1988; Goodfellow, 1992; Jacobs, et al., 1992; Keel et al., 2001; Balzer and Weiss 2009, Mallick et al. 2009). Lymphomas have also been reported in association with the capsules surrounding breast implants (Keech and Creech, 1997; Gaudet et al., 2002; Sahoo et al., 2003; Visuri et al., 2006a; Mallick et al., 2009). A non-implant-related primary tumor (gastric cancer) with a metastasis to a total knee replacement also has been reported (Kolstad and Hgstorp, 1990).

Whether there is a casual role for implanted medical devices in local or distant malignancy in general or in specific cases remains controversial. In an individual case, caution is necessary in implicating the implant in the formation of a neoplasm; clearly, demonstration of a tumor occurring adjacent to an implant does not necessarily prove that the implant caused the tumor.

FIGURE II.2.7.2 Orthopedic implant-related osteosarcoma in a 68-year-old man three years following total hip replacement. (A) Radiograph demonstrating the osteoblastic (i.e., bone-making) tumor surrounding the implant. (B) Photo of the tumor, showing its relationship to the implant and partially destroyed proximal femur. (C) Photomicrograph of tumor, demonstrating high-grade osteosarcoma. The cytologically malignant cells surround coarse lace-like neoplastic bone.

(Courtesy of Andrew E. Rosenberg, M.D., Department of Pathology, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA. (A) and (B) reproduced by permission from Keel, S. B. et al. (2001). Orthopaedic implant-related sarcoma: A study of twelve cases. Mod. Pathol. 14, 969–977.)

TABLE II.2.7.2 Tumors Associated with Implant Sites in Humans: Representative Reports

aMaterials: D: Dacron; PMMA: poly(methacrylate) bone cement; SS: stainless steel; Ti: titanium; UHMWPE: ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene; V: Vitallium.

bTumor types: AS: angiosarcoma; ES: epithelioid sarcoma; L: lymphoma; MFH: malignant fibrous histiocytoma; OS: osteosarcoma; RS: rhapdomyosarcoma; SS: synovial sarcoma; STS: soft tissue sarcoma.

Whether there is a causal role for implanted medical devices in local or distant malignancy in general or in specific cases remains controversial. In an individual case, caution is necessary in implicating the implant in the formation of a neoplasm; clearly, demonstration of a tumor occurring adjacent to an implant does not necessarily prove that the implant caused the tumor (Morgan and Elcock, 1995). Large-scale epidemiological studies and reviews of available data have concluded that there is no evidence in humans for tumorgenicity of non-metallic and metallic surgical implants (McGregor et al., 2000). Indeed, the risk in populations must be low, as exemplified by the recent cohorts of patients with both total hip replacement and breast implants that show no detectable increases in tumors at the implant site (Deapen and Brody, 1991; Berkel et al., 1992; Mathiesen et al., 1995; Brinton and Brown, 1997; Visuri, 2006b). Although cancers at most other (systemic) sites seem not to be increased, some studies suggest that there may be a slightly increased risk of the hematopoietic cancers (i.e., leukemias and lymphomas). Such cancers occur in organs where exogenous elements and particles may accumulate (e.g., lymph nodes); in this regard, one study suggests enhanced surveillance in total hip recipients with metal-on-metal articulations, in which the number of metallic particles is estimated to be much higher than with metal-on-plastic bearings (Visuri, 2006b), and the size of the particles smaller, with a correspondingly high reactive surface area. One clinical and experimental study suggested that the incidence of breast carcinoma may actually be decreased in women with breast implants (Su et al., 1995). Importantly, the presence of a breast implant does not impair the diagnosis of breast cancer (Brinton and Brown, 1997).

Moreover, neoplasms are common in both humans and animals, and can occur naturally at sites where biomaterials are implanted. Spontaneous human sarcomas in musculoskeletal sites are not unusual. Most clinical veterinary cases have been observed in dogs, a species with a relatively high natural frequency of osteosarcoma, and other tumors at sites where orthopedic devices are implanted. However, since sarcomas arising in the aorta and other large arteries are particularly rare, the association of primary vascular malignancies with clinical polymeric grafts may be stronger than that with orthopedic devices (Weinberg and Maini, 1980).

A possible association between anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and breast implants, which has received recent attention from the FDA (Center for Devices and Radiological Health, FDA, 2011), exemplifies the difficulties in assessing cause-effect relationships with implant-associated tumors. Firstly, it is not possible to confirm with statistical certainty that breast implants cause ALCL. ALCL is extremely rare, and women with breast implants may have a very small but increased risk of developing this disease in the scar capsule adjacent to the implant (and not in other sites within the breast tissue). No association of risk with type of implant (silicone versus saline) or a reason for implant (reconstruction versus augmentation) has been established. ALCL has been identified most frequently in patients undergoing implant revision operations for late onset, persistent peri-implant fluid collection (seroma), with implant durations reported to vary from 3 to 23 years. Some researchers have suggested that breast implant-associated ALCL may represent a new clinical entity with less-aggressive (indolent) behavior than ALCL not associated with implants (Miranda et al., 2009).

Benign but exuberant foreign-body reactions may simulate neoplasms. A fibrous lesion caused by a foreign-body reaction which masquerades as neoplasm is often called pseudotumor. For example, fibrohistiocytic lesions resembling malignant tumors may occur as a reaction to silica, previously injected as a soft tissue sclerosing agent (Weiss et al., 1978), and exuberant fibrohistiocytic lesions have been reported in associated with the capsules forming around breast implants (Balzer and Weiss, 2009) and a polytetraethylene sleeve used in association with a lung cancer resection (Fernandez et al., 2008). Moreover, regional lymphadenopathy (i.e., enlargement of lymph nodes) may result from an exuberant foreign-body reaction to material which has migrated from a prosthesis through lymphatic vessels. This has been documented in cases of silicone emanating from both finger joints (Christie et al., 1977) and breast prostheses (Hausner et al., 1978), as well as in association with polymeric replacements of the temporomandibular joint, and with conventional metallic, ceramic, and polymeric total replacements of large joints (Jacobs et al., 1995).

Exuberant fibro-inflammatory lesions have been reported recently with breast implants, metal-on-metal hip replacements, and other implants. For example, such lesions have been reported in associated with the capsules forming around breast implants (Blazer, 2009) and a polytetraethylene sleeve used in association with a lung cancer resection (Fernandez, 2008). Moreover, locally-destructive pseudotumors have been reported recently in association with failed metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty and may occur in as many as 1% of patients who have had metal-on-metal resurfacings (Kwon et al, 2010; Ebramzadeh et al, 2011; Guyer et al, 2011). The cause is presently unknown, but a toxic and/or hypersensivity reaction to a high rate of particulate wear debris is considered to be a central feature.

Pathobiology of Foreign-Body Tumorigenesis

Considerable progress has been made over the last several decades toward understanding the molecular basis of cancer (Kumar et al., 2010). Four principles are fundamental and well-accepted: (1) neoplasia is associated with, and often results from, non-lethal genetic damage (or mutation), either inherited or acquired by the action of environmental agents such as physical effects (e.g., radiation, fibers or foreign bodies; Fry, 1989), chemicals or viruses; (2) the principal targets of the genetic damage are cellular regulatory genes (normally present and necessary for physiologic cell function, inducing cellular replication, growth, and repair of damaged DNA); (3) the tumor mass evolves from the clonal expansion of a single progenitor cell which has incurred the genetic damage; (4) tumorigenesis is a multistep process, generally owing to accumulation of successive genetic lesions. After a tumor has been initiated, the most important factors in its growth are the kinetics (i.e., balance of replication or loss) of cell number change and its blood supply. The formation of new vessels (called angiogenesis) is essential for enlargement of tumors, and for their access to the vasculature, and hence, metastasis.

The pathogenesis of implant-induced tumors is not well-understood, yet most experimental data indicated that physical effects rather than the chemical characteristics of the foreign-body are the principal determinants of tumorigenicity.

The pathogenesis of implant-induced tumors is not well-understood, yet most experimental data indicate that physical effects rather than the chemical characteristics of the foreign-body are the principal determinants of tumorigenicity (Brand et al., 1975). Tumors are induced experimentally by a wide array of materials of diverse composition, including those that could be considered essentially nonreactive, such as certain glasses, gold or platinum, and other relatively pure metals and polymers. Indeed, one surgeon performed a much-maligned experiment in which coins inserted in rats yielded a rate of 60% sarcomas in 16 months (prompting the suggestion that probably all metallic coins were carcinogenic and should be discontinued!) (Moore and Palmer, 1997). Solid materials implanted in a configuration with high surface area are most tumorigenic. Materials lose their tumorigenicity when implanted in pulverized, finely shredded or woven form, or when surface continuity is interrupted by multiple perforations. This trend is often called the Oppenheimer effect. Thus, foreign-body neoplasia is generally considered to be a transformation process mediated by the physical state of implants; it is largely independent of the composition of the materials, unless specific carcinogens are present. However, recent evidence suggests that tumor formation induced by nanoparticles is dependent on both the physical and chemical properties in a particle-dependent preneoplasia-neoplasia model (Hansen et al., 2006). Clearly, more detailed studies regarding the physical and chemical particle–tissue interactions are of vital interest for our understanding of the use of nanoparticles in medicine.

Solid-state tumorigenesis depends on the development of a fibrous capsule around the implant, a process that involves myofibroblasts (Hinz et al., 2007), mesenchymal cells which could be involved in tumor formation. Tumorigenicity corresponds directly to the extent and maturity of tissue encapsulation of a foreign-body, and inversely with the degree of active cellular inflammation. Thus, an active, persistent inflammatory response inhibits tumor formation in experimental systems. Host (especially genetic) factors also affect the propensity to form tumors as a response to foreign-bodies. Humans are less susceptible to foreign-body tumorigenesis than rodents, the usual experimental model. In rodent systems, tumor frequency and latency depend on species, strain, sex, and age. Concern has been raised over the possibility that foreign-body neoplasia can be induced by the release of wear debris or needle-like elements from composites in a mechanism that is analogous to that of asbestos-related mesothelioma (Brown et al., 1990; Jurand, 1991). However, animal experiments suggest only particles with very high length-to-diameter ratios (>100) produce this effect. Particles with this high aspect ratio are highly unlikely to arise as wear debris from orthopedic implants.

Nevertheless, cancer at foreign-body sites may be mechanistically related to that which occurs in diseases in which tissue fibrosis is a prominent characteristic, including asbestosis (i.e., lung damage caused by chronic inhalation of asbestos), lung or liver scarring, or chronic bone infections (Brand, 1982; Robinson et al., 2005). However, in contrast to the mesenchymal origin of most implant-related tumors, other cancers associated with scarring are generally derived from adjacent epithelial structures (e.g., mesothelioma with asbestos).

Chemical induction effects are also possible. With orthopedic implants, the stimulus for tumorigenesis could be metal particulates released by wear of the implant (Harris, 1994). Indeed, implants of chromium, nickel, cobalt, and some of their compounds, either as foils or debris, are carcinogenic in rodents (Swierenza et al., 1987), and the clearly demonstrated widespread dissemination of metal debris from implants (to lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver and spleen, particularly in subjects with loose, worn joint prostheses) could not only cause damage to distant organs, but also could be associated with the induction of neoplasia (Case et al., 1994). Although unequivocal cases of metal particles or elemental metals provoking the formation of malignant tumors are not available, continued vigilance and further study of the problem in animal models is warranted (Lewis and Sunderman, 1996).

“Nonbiodegradable” and “inert” implants have been shown to contain and/or release trace amounts of substances such as remnant monomers, catalysts, plasticizers, and antioxidants. Nevertheless, such substances injected in experimental animals at appropriate test sites (without implants) in quantities comparable to those found adjacent to implants, are generally not tumorigenic. Moreover, chemical carcinogens, such as nitrosamines or those contained in tobacco smoke, may potentiate scar-associated cancers.

A chemical effect has been considered in the potential carcinogenicity of polyurethane biomaterials (Pinchuk, 1994). Under certain conditions (i.e., high temperatures in the presence of strong bases), diamines called 2,4-toluene diamine (TDA) and 4,4′-methylene dianiline (MDA) can be produced from the aromatic isocyanates used in the synthesis of polyurethanes. TDA and MDA are carcinogenic in rodents. However, it is uncertain whether: (1) TDA and MDA are formed in vivo; and (2) these compounds are indeed carcinogenic in humans, especially in the low dose rate provided by medical devices. Although attention has been focused on polyurethane foam-coated silicone gel-filled breast implants, one type of which contained the precursor to TDA, the risk is considered zero to negligible (Expert Panel, 1991).

Foreign-body tumorigenesis is characterized by a long latent period, during which the presence of the implant is required for tumor formation. Available data suggest the following sequence of essential developmental stages in foreign-body tumorigenesis: (1) cellular proliferation in conjunction with tissue inflammation associated with the foreign-body reaction (specific susceptible preneoplastic cells may be present at this stage); (2) progressive formation of a well-demarcated fibrotic tissue capsule surrounding the implant; (3) quiescence of the tissue reaction (i.e., dormancy and phagocytic inactivity of macrophages attached to the foreign body), but direct contact of clonal preneoplastic cells with the foreign-body surface; (4) final maturation of preneoplastic cells; and (5) sarcomatous proliferation. Support for this multistep hypothesis for foreign-body tumorigenesis comes from an experimental study by Kirkpatrick et al. (2000), in which premalignant lesions were frequently found in implant capsules. A spectrum of lesions was observed, from proliferative lesions without atypical calls, to atypical proliferation, to incipient sarcoma.

The essential hypothesis is that initial acquisition of neoplastic potential and the determination of specific tumor characteristics do not depend on direct physical or chemical interaction between susceptible cells and the foreign-body and, thus, the foreign-body per se probably does not initiate the tumor. However, although the critical initial event occurs early during the foreign-body reaction, the final step to neoplastic autonomy (presumably a genetic event) is accomplished only when preneoplastic cells attach themselves to the foreign-body surface. Subsequently, there is proliferation of abnormal mesenchymal cells in this relatively quiescent microenvironment, a situation not permitted with the prolonged active inflammation associated with less inert implants. Interestingly, a study, using a model of biomaterial-induced sarcoma formation in which preneoplastic changes in both tumors and the foreign-body-induced fibrous capsule can be studied by contemporary histologic and molecular techniques (Kirkpatrick et al., 2000), suggested that biomaterials-associated tumorigenesis does not occur by a specific genetic insult, and thereby is different from spontaneous tumorigenesis (Weber et al., 2009). The significance of this observation is not yet apparent.

Thus, the critical factors in sarcomas induced by foreign-bodies include implant configuration, fibrous capsule development and remodeling, and a period of latency long enough to allow progression to neoplasia in a susceptible host. The major role of the foreign-body itself seems to be that of stimulating the formation of a fibrous capsule conducive to neoplastic cell maturation and proliferation, by yet poorly-understood mechanisms. The rarity of human foreign-body-associated tumors suggests that cancer-prone cells are infrequent in the foreign-body reactions to implanted medical devices in humans.

A new set of considerations related to tumorigenesis has arisen with the use of stem cells in tissue engineering and regenerative therapeutics.

A new set of considerations related to tumorigenesis has arisen with the use of stem cells in tissue engineering and regenerative therapeutics. It is well known that similar mechanisms underly developmemtal processes, would healing and tumor formation (Friedl and Gilmour, 2009). The possibility of tumor stimulation by autologous stem cells is probably minimal or absent (Brittberg et al., 1994), but embryonic stem cells (ESC) isolated from the mouse and human are pleuripotent, and have robust tumorigenicity as each readily forms teratomas when transplanted in vivo (Blum and Benvenisty, 2008). Human-induced pleuripotent stem cells (IPSC) are predicted to have a tumorigenic potential at least as great as ESCs (Knoeppler, 2009). This issue is certain to generate considerable research and controversy over the next several years.

Conclusions

Neoplasms associated with therapeutic clinical implants in humans are rare, and causality is difficult to demonstrate in any individual case. Experimental implant-related tumors are induced by a large spectrum of materials and biomaterials, dependent primarily on the physical, and not the chemical, configuration of the implant. The mechanism of experimental tumor formation remains incompletely understood. The potential for tumors associated with therapeutic applications of stem cells must be considered.

Bibliography

1. Adams JE, Jaffe KA, Lemons JE, Siegal GP. Prosthetic implant associated sarcomas: A case report emphasizing surface evaluation and spectroscopic trace metal analysis. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2003;7:35–46.

2. Aladily TN, Mederious LJ, Alayed K, Miranda RN. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a newly recongnized entity that needs further refinement of its definition. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:749–750.

3. Bago-Granell J, Aguirre-Canyadell M, Nardi J, Tallada N. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma at the site of a total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66B:38–40.

4. Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Do biomaterials cause implant-associated mesenchymal tumors of the breast? Analysis of 8 new cases and review of the literature. Human Path. 2009;40:1564–1570.

5. Berkel H, Birdsell DC, Jenkins H. Breast augmentation: A risk factor for breast cancer?. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1649–1653.

6. Black J. Orthopedic Biomaterials in Research and Practice. New York, NY: Churchill-Livingstone; 1988; (pp. 1–394.

7. Blum B, Benvenisty N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic stem cells. Adv Cancer Res. 2008:100, 133–158.

8. Brand KG. Cancer associated with asbestosis, schistosomiasis, foreign bodies and scars. In: Becker FF, ed. New York, NY: Plenum Pub; 1982:661–692. Cancer: A Comprehensive Treatise. Vol. I 2nd ed.

9. Brand KG, Buoen LC, Johnson KH, Brand I. Etiological factors, stages and the role of the foreign body in foreign body tumorigenesis: A review. Cancer Res. 1975;35:279–286.

10. Brinton LA, Brown SL. Breast implants and cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1341–1349.

11. Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, et al. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889–895.

12. Brown RC, Hoskins JA, Miller K, Mossman BT. Pathogenetic mechanisms of asbestos and other mineral fibres. Mol Aspects Med. 1990;11:325–349.

13. Center for Devices and Radiological Health, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) In Women with Breast Implants: Preliminary FDA Findings and Analyses. 2011; In: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/BreastImplants/ucm239996.htm; 2011.

14. Case CP, Langkamer VG, James C, Palmer MR, Kemp AJ, et al. Widespread dissemination of metal debris from implants. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1994;76-B:701–712.

15. Christie AJ, Weinberger KA, Dietrich M. Silicone lymphadenopathy and synovitis Complications of silicone elastomer finger joint prostheses. JAMA. 1977;237:1463–1464.

16. Deapen DM, Brody GS. Augmentation mammaplasty and breast cancer: A 5-year update of the Los Angeles study. Mammaplast Breast Cancer. 1991;89:660–665.

17. Expert Panel on the Safety of Polyurethane-covered Breast Implants. Safety of polyurethane-covered breast implants. Can Med Assoc J. 1991;145:1125–1132.

18. Ebramzadeh E, Campbell PA, Takamura KM, et al. Failure modes of 433 metal-on-metal hip implants: How, why, and wear. Orthop Clin N Am. 2011;42:241–250.

19. Fehrenbacker JW, Bowers W, Strate R, Pittman J. Angiosarcoma of the aorta associated with a Dacron graft. Ann Thorac Surg. 1981;32:297–301.

20. Fernandez S, de Castro PL, Tapia G, Astudillo J. Pseudotumor associated with polytetrafluoroethylene sleeves. Eur J Cardio Surg. 2008;33:937–938.

21. Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457.

22. Fry RJM. Principles of carcinogenesis: Physical. In: DeVita V, ed. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. 3rd ed. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott-Raven; 1989;136–148.

23. Gaudet G, Friedberg JW, Weng A, Pinkus GS, Freedman AS. Breast lymphoma associated with breast implants: Two case-reports and a review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:115–119.

24. Goodfellow J. Malignancy and joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B:645.

25. Grubitzsch H, Wollert HG, Eckel L. Sarcoma associated with silver coated mechanical heart valve prosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1730–1740.

26. Guyer RD, Shellock J, MacLennan B, et al. Early failure of metal-on metal artificial disc prostheses associated with lymphocytic reaction. Spine. 2011;7:E492–E497.

27. Hansen T, Clermont G, Alves A, Eloy R, Brochhausen C, et al. Biological tolerance of different materials in bulk and nanoparticulate form in a rat model: Sarcoma development by nanoparticles. J R Soc Interface. 2006;3:767–775.

28. Harris WH. Osteolysis and particle disease in hip replacement. Acta Orth Scand. 1994;65:113–123.

29. Hausner RJ, Schoen FJ, Pierson KK. Foreign body reaction to silicone in axillary lymph nodes after prosthetic augmentation mammoplasty. Plast Reconst Surg. 1978;62:381–384.

30. Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, et al. The myofibroblast: One function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1807–1816.

31. Jacobs JJ, Rosenbaum DH, Hay RM, Gitelis S, Black J. Early sarcomatous degeneration near a cementless hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74B:740–744.

32. Jacobs JJ, Urban RM, Wall J, Black J, Reid JD, et al. Unusual foreign-body reaction to a failed total knee replacement: Simulation of a sarcoma clinically and a sarcoid histologically. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77:444–451.

33. Jennings TA, Peterson L, Axiotis CA, Freidlander GE, Cooke RA, et al. Angiosarcoma associated with foreign body material A report of three cases. Cancer. 1988;62:2436–2444.

34. Jurand MC. Observations on the carcinogenicity of asbestos fibers. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;643:258–270.

35. Keech Jr JA, Creech BJ. Anaplastic T-cell lymphoma in proximity to a saline-filled breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:554–555.

36. Keel SB, Jaffe KA, Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE. Orthopaedic implant-related sarcoma A study of twelve cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:969–977.

37. Kirkpatrick CJ, Alves A, Kohler H, Kriegsmann J, Bittinger F, et al. Biomaterial-induced sarcoma A novel model to study preneoplastic change. Am J Path. 2000;156:1455–1467.

38. Kolstad K, Hgstorp H. Gastric carcinoma metastasis to a knee with a newly inserted prosthesis. Acta Orth Scand. 1990;61:369–370.

39. Knoeppler PS. Deconstructing stem cell tumorigenicity: A roadmap to safe regenerative medicine. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1050–1056.

40. Kumar V, Fausto N, Aster JC, Abbas A, eds. Cotran and Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2010.

41. Kwon YM, Thomas P, Summer B, et al. Lymphocyte proliferation responses in patients with pseudotumors following metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthoplasty. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:444–450.

42. Lamovec J, Zidar A, Cucek-Plenicar M. Synovial sarcoma associated with total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:1558–1560.

43. Lewis CG, Sunderman Jr FW. Metal carcinogenesis in total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Related Res. 1996;329S:S264–S268.

44. Mallick A, Jain S, Proctor A, Pandey R. Angiosarcoma around a revision total hip arthroplasty and review of literature. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:323.

45. Martin A, Bauer TW, Manley MT, Marks KH. Osteosarcoma at the site of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:1561–1567.

46. Mathiesen EB, Ahlbom A, Bermann G, Lindsgren JU. Total hip replacement and cancer A cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77B:345–350.

47. McDonald W. Malignant lymphoma associated with internal fixation of a fractured tibia. Cancer. 1980;48:1009–1011.

48. McGregor DB, Baan RA, Partensky C, Rice JM, Wilbourn JD. Evaluation of the carcinogenic risks to humans associated with surgical implants and other foreign bodies – a report of an IARC Monographs Programme Meeting. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:307–313.

49. Moore GE, Palmer QN. Money causes cancer Ban it. JAMA. 1977;238:397.

50. Morgan RW, Elcock M. Artificial implants and soft tissue sarcomas. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:545–549.

51. Pinchuk L. A review of the biostability and carcinogenicity of polyurethanes in medicine and the new generation of “biostable” polyurethanes. J Biomater Sci Polymer Edn. 1994;6:225–267.

52. Pedley RB, Meachim G, Williams DF. Tumor induction by implant materials. In: Williams DF, ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1981;175–202. Fundamental Aspects of Biocompatibility. Vol. II.

53. Robinson BW, Musk AW, Lake RA. Malignant mesothelioma. Lancet. 2005;366:397–408.

54. Ryu RKN, Bovill Jr EG, Skinner HB, Murray WR. Soft tissue sarcoma associated with aluminum oxide ceramic total hip arthroplasty A case report. Clin Orth Rel Res. 1987;216:207–212.

55. Sahoo S, Rosen PP, Feddersen RM, Viswanatha DS, Clark DA. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma arising in a silicone breast implant capsule: Case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e115–e118.

56. Schoen FJ. Biomaterials-associated infection, tumorigenesis and calcification. Trans Am Soc Artif Int Organs. 1987;33:8–18.

57. Su CW, Dreyfuss DA, Krizek TJ, Leoni KJ. Silicone implants and the inhibition of cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:513–520.

58. Swierenza SHH, Gilman JPW, McLean JR. Cancer risk from inorganics. Cancer Metas Rev. 1987;6:113–154.

59. Visuri T, Pulkkinen P, Paavolainen P. Malignant tumors at the site of total hip prosthesis Analytic review of 46 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2006a;21:311–323.

60. Visuri TI, Pukkala E, Pukkinen P, Paavolainen P. Cancer incidence and causes of death among total hip replacement patients: A review based on Nordic cohorts with a special emphasis on metal-on-metal bearings. Proc Imech E. 2006b;220:399–407.

61. Ward JJ, Dunham WK, Thornbury DD, Lemons JE. Metal-induced sarcoma. Trans Soc Biomater. 1987;10:106.

62. Weber PC. Epithelioid sarcoma in association with total knee replacement A case report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68B:824–826.

63. Weber A, Strehl A, Springer E, Hansen T, Schad A, et al. Biomaterial-induced sarcomagenesis is not associated with microsatellite instability. Virschow’s Arch. 2009;454:195–201.

64. Weinberg DS, Maini BS. Primary sarcoma of the aorta associated with a vascular prosthesis A case report. Cancer. 1980;46:398–402.

65. Weiss SW, Enzinger FM, Johnson FB. Silica reaction simulating fibrous histocytoma. Cancer. 1978;42:2738–2743.

66. Wolkenhauer O, Fell D, De Meyts P, Blűthgen N, Herzel H, et al. SysBioMed report: Advancing systems biology for medical applications. IET Sys Biol. 2009;3:131–136.