CHAPTER TWO

Plant Fibres

Cotton

The cotton plant, of the genus Gossypium (named by Carl Linnaeus in his Species

Plantarum in 1753), first appeared in the warm and moist corners of the world seven million years ago or thereabouts.

Cotton in two continents

The seeds of the different wild varieties blew hither and thither across the globe on their tiny filaments and cross-fertilised with other cotton plants to create new types. Although there are more than 50 kinds of cotton plants in the world today, only four varieties bear fibres suitable for spinning into thread.

Interestingly, these four varieties, all belonging to the swamp mallow family Gossypium malavaceae, can be split into two groups, two of which evolved in Africa and Asia and the other two in Central and Southern America. One theory explaining this split is that when Gondwanaland separated and drifted into distinct continents the cotton species thrived and developed in the two hemispheres. While this may explain the initial division of the same plant developing on different continents, it has also been found that there has been a long history of cross-fertilisation of the different species, evolving into the four distinct varieties suitable for spinning. Hybridisation, through natural and man-made interference, has worked in harmony to produce a textile that forms one of the world’s largest industries.

Gossypium arboretum is native to the Indus Valley region (modern day Pakistan) spreading to Nubia (where it was cultivated by the Meroe people who were the first African civilisation to weave textiles), and Nigeria in Africa and Gossypium herbaceum was found in sub-Saharan Africa then eventually made its way to China. On the other side of the world Gossypium barbadense first grew in Chile and Peru while Gossypium hirsutum flourished in Central America and Mexico.

The history of the cultivation of the cotton plant and its use as a fibre for spinning into thread and weaving into cloth appears to have as close a parallel history in both eastern and western hemispheres as the evolution of the cotton plant itself. However, the archaeological evidence is by far the most prevalent in Asia, Europe and Africa than it is in the Americas.

The Indus Valley

There is strong proof in the findings of the remains of cotton thread that the cultivation of cotton as a textile fibre began in the Indus River Valley (the site of modern Pakistan) about 5,500 years ago. This date is approximately the same for the cotton fibres found in Mexican Caves in the Tehaucan Valley, evidence supported by fossil findings in other parts of South America that date to 2,900 BC. Remains of cotton thread, dated to 2,500 BC, show that Peruvians were using cotton thread to make fishing nets.

Cotton was being cultivated in India and the Indus Valley and traded with other countries as long ago as 5,000 BC. For the Harappan civilisation of the Indus Valley, cotton textiles were a major industry and even though they were domesticating sheep and cattle at the same time as they were refining their cotton, it was the latter, not animal wool that was the more successful export. After the decline of the Harappan people, around 1000 – 900 BC the area they had inhabited and its neighbouring surrounds continued to produce much of the cotton products in the Old World.

Cotton in Egypt

From the Indus valley the growing and use of cotton for making fabric spread to Mesopotamia and Egypt. A statue excavated in one of the Indus Valley sites wore a sculpted stole over its shoulders with a detailed pattern etched into its stony surface. Apparently it was the spitting image of an actual textile found in the tomb of Tutankhamen in Egypt. This evidence would then suggest that the Harappan people traded in cotton textiles from a very early time.

Egypt’s fertile Nile flood plain was an excellent location for growing cotton. The annual flooding brought essential nutrients to the soils that were quickly depleted from them by the ever hungry cotton crop. While Egypt did produce large quantities of cotton and cotton fabric, their own people tended to wear linen clothing, keeping the fine cotton for special occasions only. The Egyptian priests would don cotton robes to undertake special ceremonies. The quality of the finished material was similar, or even superior to that produced by India.

The Greeks

While the fabric was known to the ancient Greeks, it was an import and not produced locally. Herodotus, in the Fifth Century BC says of the cotton plant, ‘there are trees which grow wild there, the fruit thereof is a wool exceeding in beauty and goodness that of a sheep. The natives make their clothes of this tree-wool’ (Book 111, ch. 103 – 107). The fact that Herodotus claims the cotton plants grew wild shows that countries relying on imported fabric remained highly ignorant of its cultivation, not unlike the ignorance surrounding the farming and processing of silk. The first written evidence of cotton is from Herodotus and the first mention of trade in the fabric was in Periplus on the Erythrean Sea.

When Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, took his troops to India in 326 BC they were all intrigued by this lightweight fabric resembling the finest of fine linen but which grew in a fleecy down on shrubs.

Sir John Mandeville claimed to have seen cotton growing as lambs on trees.

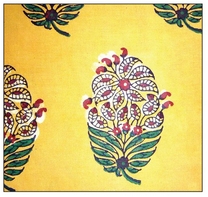

Ablock printed cotton fabric from India, picture courtesy of the Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur.

They stuffed the wool-like substance into their saddles as wadding, marvelling at the ‘tree-wool’, and introduced it to Macedonia and Greece. From Greece it found its way to Rome where it was considered a luxurious fabric.

One of Alexander the Great’s generals, Nearchus, founded a Macedonian colony in the Indus Valley. He was in great admiration of a flowery printed, lightweight cotton fabric called ‘chintz’ which hundreds of years later caused such a big sensation in Europe in the Eighteenth Century.

In the Seventh and Eighth Centuries AD, Hebrew and Phoenician merchants traded in cotton fabric across the known world outside Europe.

Cotton arrives in Europe

Before the introduction of cotton fabric into Europe, the main textiles were made from wool or linen, or a mixture of the two. The Moors took cotton and the secrets of its spinning and weaving to Spain in the early Middle Ages.

Vasco da Gamma, the Portuguese explorer, loaded his ship with calico on his return exploratory trip from Lisbon, around the Cape of Good Hope to Calcutta. The opening of this new trade route meant that Spain and Portugal became leading traders in cotton.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic …

Cotton bolls were being carded, spun and woven into fabric by the native people of the West Indies. Captain Gonzalo Fernandez De Oviedo wrote of Christopher Columbus’s first encounter with some of the indigenous people in his log book of 1492 – 3. When they saw the European ship the natives swam out to meet it carrying gifts for those on board which included parrots and balls of string. Despite the technology to spin thread they did not appear to wear clothes.

In exchange for the equivalent of a farthing, one native gave a sailor, 16 balls of cotton which would fetch about 25 pounds back in Europe. Gonzalo says he would have liked to forbid such goings on and trade with the Indians himself on behalf of his Majesties. He does not say he would offer a better exchange rate for it.

A few days later the sailors arrived at an island where cotton cloth was woven. On the 5th November, two members of the crew went off exploring and when they returned told of what they had seen.

The cotton plant.

They had a great abundance of cotton spun into balls, so much that a single house contained more than 12,500lb of yarn. They do not plant it by hand, for it grows naturally in the fields like roses, and the plants open spontaneously when ripe, though not all at the same season. For one plant they saw a half-formed pod, an open one, and another so ripe that it was falling. The Indians afterwards brought a great quantity of these plants to the ships, and would exchange a whole basket for a leather tag. Strangely enough, none of the Indians made use of this cotton for clothing, but only for making their nets and beds – which they call hammocks – and for weaving the little skirts or cloths which the women wore to cover their private parts.1

During the second voyage, 1493 – 6, Dr Chanca, court physician who accompanied Columbus, writes of their travels in a letter made to the City of Seville. Firstly he talks about their stay on the island of Guadalupe. The people there, he says, were of a gentle and industrious disposition.

These people seem to us more civilised than those elsewhere. All have straw houses, but these people build them much better, and have larger stocks of provisions, and show more signs of industry practised by both men and women. They have much cotton, spun and ready for spinning, and much cotton cloth so well woven that it is in no way inferior to the cloth of our own country.2

In marked contrast, Chanca writes, with the wild Carib people (who have cannibalistic tendencies, and their custom of wearing two woven cotton braids, one just below the knee and the other at the ankle). On the island, christened Isabela, in honour of the Spanish queen, Chanca goes on land himself. He sees marvellous trees, not with animals hanging out of the pods but which:

… bear very fine wool, so fine that those who understand weaving say that good cloth could be woven from it. These trees are so numerous that the caravels could be fully laden with the wool, though it is hard to gather, since they are very thorny, but some means of doing so could easily be devised. There is also an infinite amount of cotton growing on trees the size of peach trees …3

The wool bearing trees have since been identified as the ceiba or silk cotton tree.

South America

Columbus had discovered cotton growing wild in the Caribbean that was spun by the natives into thread, and sometimes woven into fabric. Later Cortez, Pizarro and other Spanish Conquistadors, were astounded to find that the inhabitants of New World Peru not only could spin and weave cotton into high quality fabric but that they wore it as well.

Cotton in Britain

Cotton cannot grow in the English climate. Britain has always had to rely on imported raw material in order to feed its thriving cotton textile industry. In the past it imported cotton from India, America, Egypt and Australia.

The art of making fabric out of cotton came from the Netherlands during the Sixteenth Century. Within a century mills for spinning and weaving cotton had sprung up. Cotton overtook the traditional spinning and weaving of flax as a popular textile, though it was never seen as a rival to wool cloth.

Cotton in America

When England claimed parts of America as British territory it took advantage of the new land’s climate to establish cotton plantations. The first of these was in Virginia in 1607. The seeds were brought from the West Indies. The first crops were experimental but the plants grew so well and were so prolific that cotton plantations sprang up across the south.

By 1640 the growers of cotton, linen and wool were being offered cash incentives to get the textile industry up and running as an economic success. Wool and cotton were commonly woven together into a fabric known as fustian.

Within two years West Indian cotton growers were exporting their raw cotton product and the increasing demand for it meant more workers were needed to grow and harvest it. Slave trading boomed and many African people were stolen from their native land and transported in appalling conditions to the West Indies to work their lives away for someone else’s profit.

By Washington’s time it was not an idle thought that textile production, largely from home-grown cotton could become a United States mainstay, not only as an export but for the use of its own, growing population.

Interestingly, the new inventions that were revolutionising the textile industry in Britain were being exported to the States and hand production remained the main method of spinning and weaving long after the English had adapted to their new factory system.

Eli Whitney’s Cotton Gin

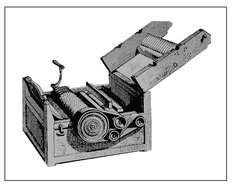

One of the most important inventions to be made in America was the cotton gin: the brain child of one Eli Whitney. It enabled cotton to be cleaned of extraneous material in a simple process by a machine that was so easily copied that Whitney’s patent was inefficient to cover it from plagiarism.

The overarching effect of Whitney’s invention was to speed up the cotton cleaning process to such an extent that the exports of raw cotton from America to Europe multiplied 700 times. Before the implementation of the cotton gin in 1791, 400 bales of cotton went to Europe from the American docks, by 1800 more than 30,000 bales annually crossed the ocean. Ten years later than this it had risen to some 180,000 bales.

Eli Whitney’s cotton gin.

Slave labour leads to American Civil War

By the time the cotton gin was in constant use consciences were turning against slavery but because the gin made it so much easier to clean the bolles it meant that more could be processed in a shorter time. It seemed impossible for the plantation owners to get rid of their labour just as the whole industry was going to make the economy boom.

One of the biggest problems with the American cotton product was the fact that it relied solely on slave labour. The plantation owners argued that they were providing a civic duty to a people who were incapable of making adult decisions. They were given clothing, food and shelter in return for their labour in the cotton fields. And the arduous task of thinking for themselves was also removed.

The ethics behind such self justifying arguments did not win everyone over and ultimately it led to civil war in America. The northern and southern states more or less divided, the former wanting to abolish slavery and the latter advocating it as a legitimate way of life and business.

Going back in time to the English Invasion of India …

Before the emergence of the cotton gin, England, in 1757, decided to invade India and take over its natural resources, including cotton.

When the act of invasion was complete and India became a colony of Britain, the Indian people virtually became slaves within their own country. They were not allowed to produce cotton fabric from their own raw product but had to cultivate and harvest it so that British textile mills could turn it into material and sell it back to the Indians at an inflated price. To make the whole matter worse, Britain used the sale of Indian cotton to supplement its slave trade to the West Indies.

England buys American cotton

By 1840 the cotton industry in India was not efficient enough to supply the mills in Britain and so England looked to America to supply extra material. American cotton by this time was of a very high quality.

Cotton mills of England

The Industrial Revolution and the rise in cotton textile manufacture in England were by and large reliant on each other. The mechanisation of the spinning and weaving of fabric was already burgeoning for wool and silk when Eli Whitney’s cotton gin revolutionised the cleaning of cotton making it far quicker to process.

Before Whitney in America, James Hargreaves, Richard Arkwright and Samuel Crompton were three of the major names in the Industrial Revolution, known for their services to the textile industry.

Arkwright put his own meagre funds, plus those of investors he managed to convince of his competence, into a cotton spinning mill in Lancashire in 1771. It was already a success with its water driven wheel before either the cotton gin or James Watt’s steam engine.

By 1778 cotton had over taken the making of woollen and linen fabrics in England: cotton reigned supreme.

Back in America

The issue over slave labour finally came to a head and civil war broke out between the northern and southern states of America.

The civil war took a heavy toll on America’s population, industry and morale. Slavery was abolished and slaves were officially made free people. However, it did not necessarily turn out happily ever after for everyone. Suddenly people who had been dependent all their lives were thrust into fending for themselves. The cotton magnates found they couldn’t work their plantations with paid labour and many former slaves were left homeless and jobless.

It took a huge effort for America to turn this economic disaster around. A business man from the south, William Gregg motivated others to set up their cotton businesses anew. Americans invented their own spinning and weaving machines and in 1881 the International Cotton Exposition in Atlanta was the perfect place to showcase them. As a consequence cotton mills sprang up everywhere and thrived. For the rest of the century and even up until World War II the industry flourished in America.

The second half of the Twentieth Century saw other factors emerge that changed cotton production. The main one of these was the invention of synthetic fabrics with their easy care qualities and inexpensive prices.

Back in Britain …

England had been more than happy to purchase American slave-produced cotton, even though they abhorred the use of slave labour. When civil war broke out American cotton was prevented from leaving the country’s shores by Union blockades, the northern Confederates thinking this move would initiate action by Britain to support their cause in the war. It did not.

Egyptian Cotton

The British and French left America to fight its own war and turned to Egypt instead. The Egyptians, encouraged by the interest from these two countries invested heavily in cotton plantations, borrowing heavily to set them up. The trade lasted only until the end of the American Civil War and then, without further thought to Egypt’s position, France and England dropped the Egyptian product and resumed trade with America. It was disastrous for Egypt which was declared bankrupt in 1876. It was no surprise then that in 1882 Egypt became an extension of the British Empire.

What happened to cotton in India?

Britain withdrew from India after the Second World War, declaring it would transfer rule back to India at the end of June 1948. It was a time of turbulence in India with fighting breaking out between the Hindu and

The charkha spinning wheel.

A hand printed cotton fabric from India, image courtesy of the Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

Muslim population. The outcome was a partition of the country into a smaller India and the New Dominion of Pakistan.

A political and spiritual leader of the time, Mahatma Gandhi (as he is known in the west) played an enormous part in the process of Indian independence. He proscribed satyagraha, civil disobedience as a means of fighting domination. It was a philosophy that advocated non violent methods of protest.

One of the important policies he introduced to the Indian National congress in 1921 was the practise of Swarja, the boycott of foreign, particularly British products. He urged his fellow Indians to go back to making and wearing khadi, homespun cloth and suggested that all citizens regardless of caste, gender, age or financial status to spend a period of time each day spinning thread to support solidarity in the movement against the British occupation.

The use of spinning and weaving as a tool to unify the people against oppression was to link India back to its ancient cultural past. Spinning and weaving were integrally linked to the Hindu belief in a balanced and unified existence, compared to a piece of fabric that goes on forever.

The Rig Veda, 1500 BC is the earliest known religious text to mention weaving. In the Artharva Veda there is a story involving two sisters, day and night, who weave warp and weft. Besides the metaphor for the continuation for life, weaving and spinning were, and still are, considered the perfect activities to accompany meditation; repetitive movement with a definite rhythm. Gandhi used his own portable spinning wheel, the charkha, to spin on everyday to accompany his meditation.

Cotton in the Twentieth Century

After the American Civil War and slave emancipation the solution to working the cotton fields came in the form of sharecropping. Freed slaves and white men without their own farms were able to work for cotton plantation owners with a view to sharing the profits from the sale of the raw material. It was a system that worked reasonably well until the introduction of machinery in the early part of the Twentieth Century. Workers were laid off then two world wars came along to occupy them all.

By 1950 new machinery was invented to facilitate the harvesting of cotton and the trade picked up so that cotton was again a major export product of the United States.

Since then the biggest competitor for cotton has been the increase in popularity of synthetic fibres. Cotton has been in and out of fashion since the sixties and now many fabrics are a mix of cotton and synthetics.

But what is cotton?

Unlike the bast fibres of flax and hemp, whose fibre comes from inside the stem of the plant, cotton fibre forms inside the seed head, called the boll, and looks like fluffy cotton wool, its appearance giving rise to the aforementioned stories.

Originally cotton grew as a perennial bush or small tree but through its domestication it is cultivated as an annual. The cultivated cotton plant grows into a bush approximately one metre high. It produces small white flowers (that turn red overnight) and later green seed pods after the petals have fallen from the flowers. Six to eight weeks after their emergence, these pods burst open revealing a mass of light, white downy stuff with small seeds attached. Left to its own devices, the cotton seeds will disperse on the wind, each carried on its own little cloud of fluff.

Properties of Cotton

The tensile strength of cotton fabric is far greater when the material is wet than when it is dry. It can withstand pressure of 30,000 to 60,000 pounds per square inch when it is wet and depending on the quality of the cotton and its processing. Another of cotton’s versatile properties is its absorbency. Cotton fibre can suck up to 27 times its own weight in water. It does not have the same fire resistant qualities of wool but it can be boiled for sterilisation purposes. A piece of woven cotton can be folded 50,000 times without damage. It is a good fabric to wear in hot and humid climates as it will absorb the excess moisture of perspiration and will dry quickly.

Processing of Cotton

To process the vegetable wool into fibre for spinning it must first be picked. This was done by hand for centuries. It was then beaten to release the seeds from the fibres and also to remove bits of dirt and other extraneous matter.

Each boll produces 20,000 or so fibres which range in size from 10 to 60 mm long, the longer the better for spinning. After the bolls have been cleaned they are pressed into bales. The bales are then sent to the cotton mill where the bales are reopened, the fibre further cleaned, dried and spread out. They are then rolled together to form a lap. It is carded to straighten the fibres out and to be pulled into a sliver from which the shorter fibres are removed. Slivers are then drawn through a roller to thin them down further and to twist them. The final strands are called roves.

Before the industrial revolution these process were all done by hand and it was very labour intensive.

Cotton’s worst nightmare

Cotton’s biggest natural fear may well be the cotton boll weevil. This insect attacks cotton crops in the spring and summer. Eggs are laid at a rate of 200 per adult female over 10 to 12 days. Each egg hatches within three days and feasts on the emerging cotton buds.

They multiply at an alarming rate, the life cycle of larvae to adult only taking three weeks. It is possible for 10 generations to exist in one season. The loss to crops is devastating.

It was at the end of the Nineteenth Century that the cotton boll weevil migrated from Mexico into the southern states of the US and from there to every cotton growing district in America. It meant huge losses in the early part of the Twentieth Century and did nothing to help the economic difficulties of the Great Depression.

In 1978 America implemented its Boll Weevil Eradication Programme which has been very successful in cotton growing areas of the world.

Another major disease is a fungus that attacks the plants via the root system and extracts all the moisture from the stem of the plant giving it the characteristic wilt which gives the fungus its name: ‘cotton wilt’ or ‘fusarium wilt’. In 1901 it did great damage to the cotton fields in Peru. It took 10 years for an enterprising Puerto Rican agriculturist, Fermin Tanguis, to come up with a viable solution. He cross-germinated various cotton plants and finally came up with a hybrid that was strong enough to resist the fungus. The cotton type took the name of its inventor, Tanguis and has been the preferred crop for Peru ever since.

The cotton boll weevil.

The modern German word for cotton is baumwolle which translates as ‘tree-wool. ’