CHAPTER THREE

Animal Fibres

Wool

Wool, the warm, insulating coat grown by members of the Caprinae family, is a protein fibre. Each single hair is made up of a medulla, cortex and cuticle.

- The medulla is the core of the hair and is fundamental to wool’s famous insulating properties

- The cortex is the component of the fibre that creates a crimp effect when it is subjected to heat and moisture. This is because the cortex is made up of two separate parts that work differently under these conditions

- The cuticle is covered in scales, situated around the base of the fibre’s core. When the fleece is growing on the sheep’s back the lanolin covered scales on each fibre deflect rain from the skin. When the greasy lanolin is washed from the fleece the scales are able to mesh together to make felt, especially when aided by heat, moisture and pressure

Wool can be left on the skin and used as a furry rug, shorn from the living animal and carded into soft rolls ready for massaging into felt or spinning into yarn to be woven, knitted, embroidered or knotted into myriad different things. It is soft, it is warm, it can deflect water, it is difficult to burn and it is used in many aspects of our lives today. It is also one of the oldest fibres manipulated by mankind and there are uses and processes that really haven’t changed dramatically in thousands of years.

Prehistoric wool

Sheep were domesticated at least 9,000 years ago. They were not necessarily bred for their fleece or even their hides. These early farmed sheep would have produced meat and milk first and then the skins would have been used for making clothing, shelter and bedding.

Sheep in their woolly coats.

It wasn’t until about 5,000 BC that sheep began to show their potential for growing wool. The amount and quality of wool that a sheep produces depends on the breed, just as with cattle, some types are bred primarily for meat, others for their milk.

It is largely the breed of sheep that determines the wool quality and amount of wool produced. How and where they are raised can affect the quality. The same type may produce extra fine or extra long fleece in one country and in another it may be considerably shorter and coarser. The fleece from one individual sheep may vary from season to season depending on the food source available, the overall health of the animal and its age. Human hair can show symptoms of disease or lack of nutrition too.

Selective breeding over centuries has produced a number of types of sheep that are well known for the particular attributes of their fleece. The earliest sheep breeding, with an idea to industry, was undertaken in south-eastern Sumeria about 5,500 years ago. By 3,000 BC there is evidence that wool was being used as a clothing textile in a broad geographical area reaching as far as Germany and Switzerland. Implements for shearing sheep have been found that date to 2,300 BC.

The wool industry in England

In Australia we talk about the economy having ridden on the sheep’s back but it would be even more relevant to apply this saying to England, which has had a flourishing wool production industry since early medieval times, possibly even earlier (wool was being woven in Britain from about 1900 BC). Wool was certainly one of the most commonly used fibres from which the native population and the subsequent invaders and settlers fashioned textiles to clothe themselves. The Romans found a thriving industry in spun and woven wool, comparing its fineness to spider’s web.

The green and pleasant land was conducive to raising sheep and not only did the animals provide meat and milk for cheese but their fleece was soft, long fibred and strong: ideal for spinning into thread.

Textiles made somewhere between the Ninth and Eleventh Centuries have been found in York. They seem to be made from the long-haired fleece of a sheep native to northern Europe. The spun thread is somewhat coarse and heavy. It contrasts dramatically with the type of fleece being produced centuries before, during the Roman occupation of Britain when sheep were brought over from the Mediterranean. At some point the different types of sheep were interbred to produce other qualities of fleece. English wool even at this early stage took dye extremely well which was an attractive characteristic.

In the Middle Ages two distinct breeds of sheep emerged from several that grazed the fields. One was a small animal with a short fleece but was very hardy and prospered on rocky mountainsides with sparse grazing and relatively poor pasture. The other type was much larger, had a longer fleece and was raised on the fenlands with its rich grass and easier living conditions.

Flanders enters the field

We might note here that across the English Channel at a similar time another country was busy raising sheep for wool. This potential rival was Flanders. It too offered excellent grazing for sheep with its low lying coastal plains that were not particularly good for general agriculture such as the growing of crops. However, even with such good pasture it was generally accepted that Flanders didn’t produce such fine fleeces as the English did.

For some time the two countries developed a largely parallel industry. In Flanders wool was so easily grown that it wasn’t long before the country had more fleece than it could use in its domestic market. Processing, spinning and weaving into cloth, was an ideal way to occupy a rapidly expanding population: lots of unemployed meant cheap labour. Cloth as a finished product became a major export for the Flemish.

Indisputably the English were able to produce a finer quality fleece than their counterparts across the water, and as the people of Flanders were putting more effort into turning their raw wool into cloth, the two countries, instead of competing with each other, decided it would make more sense for the Flemish to import fine fleece from England, weave it into fabric, dye, finish it and sell it, not only back to the English, but to many other countries in Europe and the East as well. The major centres of cloth making in Flanders were: Ypres, Ghent, Douai, St Omer, Arras and Bruges.

To keep ahead of any possible rivals in the cloth-making trade the Flemish were constantly improving techniques and developing machinery to spin and weave wool. For many years Flanders and England were content to support each other in this way: one, supplying the wool, the other turning it into exemplary cloth. In 1113 a contemporary reference suggests that the mutual trade between England and Flanders was already well established. It has been further suggested that it began as early as the Tenth Century.

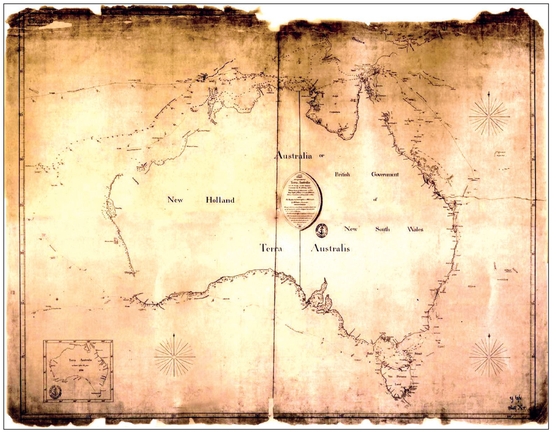

A map of trade routes in the Fourteenth Century between England and the Continent.

With an interdependent trade relationship between Flanders and England it would seem that everything was smooth sailing. But, instead of it being a rock steady one, it was fraught with problems. Perhaps it was the very nature of the interdependence that helped fan the fires of discord because, although Flanders needed English wool, they were geographically aligned with France and therefore often obliged to show support for the rulers of that country. This meant that when relationships between England and France grew unsteady, Flanders would be caught up in it, being pulled in both directions for its allegiance. Two main camps arose in Flanders: the ‘Leiliaards’ who supported the French and the ‘Klauwaarts’ who supported the English. Troubles would flair and subside countless times over the centuries and always affected trade in some way. For centuries the English wool trade and politics were inextricably linked.

For instance, King John made an enemy of Philip Augustus of France and consequently lost not only his own fiefdoms in France but also those belonging to many English barons. Then, after virtually splitting England from France, John antagonised Pope Innocent III and more trouble ensued from both outside England and within its own ruling classes as English noblemen found themselves stripped of ancient ties to France. The eventual outcome was John’s signing of the Magna Carter Treaty under order of the English barons. This caused yet another rift with the Flemish.

Here come the Italians

It was during this turmoil that John ordered goods belonging to Flemish merchants in London be seized; in the case of one unfortunate trader it meant the loss of about 18 stone (114.305 kg) of wool. To make matters worse a decree was issued that made it illegal for Englishmen to trade with Flemings unless the seller had a special license. Trading with Flanders didn’t cease, it was still one of the major importers of English wool during the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, but hostile behaviour, as exhibited by King John, meant that England needed to find other outlets for their product and as the Italians were also fine cloth makers it was natural that Italian centres like Florence offered a ready market for English wool.

Italian merchants were in an excellent position to trade with England. They were able to borrow money at lower rates of interest and therefore could pay for wool in advance, making trade with them a very attractive option.

As the demand for raw wool grew, both for the overseas and the domestic markets, different groups of people in England began to raise sheep. Cistercian monasteries were one example who, through slow and careful breeding managed to accumulate a sizeable amount of wealth. But sheep farming wasn’t just for large scale groups like monasteries or the landed gentry, anyone could graze a sheep or two on the common, shear the wool and use it for family clothing and bedding and then sell any surplus for a small but welcome profit.

It was the merchants who were making the real profit, growing so wealthy from selling wool that when Edward I imposed a tax of seven shillings sixpence per sack, they didn’t raise a murmur of protest. It must be noted, however, that when he tried to raise it a couple of decades later to 40 odd shillings a sack, the merchants were not nearly so complacent in accepting it.

In the late Thirteenth Century wool was such a profitable export for the city of York that a large amount of revenue was raised by charging a toll of one shilling per sack that was brought into or sold out of the town. Many of the merchants on whom this toll was imposed came from overseas, though there were a certain number of English merchants trading in wool too. Flemish and Italian traders were joined by German and French.

Flanders is squeezed out of the market

1270 saw the culmination of more strife with Flanders and Edward I had all Flemish merchants in England arrested. This meant that the other European merchants were given the opportunity to gain ground in the wool business. While the Flemish had been prepared to travel around the countryside to buy wool the Germans and Italians preferred to stay in London and leave the gathering of the raw product to London merchants.

In 1287 when the English lifted their ban on trade with Flanders, the Flemish merchants found that their position as number one wool buyers had been superseded by other Europeans and were eventually eased out altogether as exporters of English wool.

Florence as master cloth makers

In the meantime Florence had emerged as another great centre of cloth manufacture and the Italian ships sailed to London ports full of exotic wares for the English (and particularly the London) market then loaded up with fine English wool to carry home. The Fourteenth Century historian and financier, Giovanni Villani, commented on the shape of the city of Florence. It was shaped like a cross and the Arte della Lana, the guild centre for woollen cloth manufacturers, lay at its centre. This was symbolic of the importance of spinning and weaving cloth to the local economy. Approximately a third of the population depended on the cloth industry for its livelihood, one way or another. It was estimated that in the 1330s, Florence sold more than 80,000 rolls of finished cloth and that it brought in about 1,200,000 florins: the worth of two kings’ ransoms.

Merchants, merchants everywhere: foreign merchants in England

In fact, the growth in numbers of merchants from outside England coming to English cities to buy wool (and other goods) became a perceived threat to the local population. In York, in the early part of the Fourteenth Century, citizens put together a petition requesting that a law be made forbidding foreigners to stay more than 40 days in their city on a single visit.

While English merchants despised and distrusted the foreign counterparts and wanted strict measures put in place to keep them under control while on English soil, the king and his government tended quite often to lean in favour of the outsiders.

In 1303 Edward I issued a charter called the Carta Mercatoria. It virtually threw open trade within England to traders from Germany, France, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands by exempting them from paying the usual tolls and tariffs imposed by the staple towns. It also gave the foreigners licence to stay where and when they liked within England, not compelling them to stay with native merchants and lifting the restrictions on how long they stayed. It overturned nearly all the strategies formally put in place to keep trade fair and regulated for the English merchants.

In 1311 under the newly appointed King Edward II, the following ordinances were made:

Item, it is ordained that the customs of the kingdom shall be received and kept by men of the kingdom itself, and not by aliens; and that the issues and profits of the same customs, together will all other issues and profits pertaining to the kingdom from any source, shall in their entirety come to the king’s exchequer and be paid to the treasurer …

Also new customs have been levied and the old have been increased upon wool, cloth … and other things – whereby [our] merchants come more rarely and bring fewer goods into the country, while alien merchants reside longer than they used to, and by such residence things become dearer than they used to be, to the damage of the king and his people – we ordain that all manner of customs and maltotes levied since the coronation of King Edward [that is Edward I], son of king Henry, are to be entirely removed and utterly abolished forever …1

Even though ordnances of this sort were put in place the trend for trade within England to be carried out by foreign merchants continued until the end of the Fourtheenth Century. It has been suggested that this may be attributed to the English merchants’ lack of economic wiles and capital to travel outside their own country in order to find customers for their wool. Of course, this was already changing. The Merchants of the Staple, for whom a patent roll was made in 1313 by Edward III, were indeed such traders who based themselves eventually in Calais. Besides, England was free of the kind of civil strife that afflicted other countries and the general peace was conducive to the raising of fat, woolly sheep without fear of raids by marauding neighbours.

England traded with many European countries, including parts of Scandinavia, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Spain and Italy. Flanders, Germany and Italy were the principal ones.

Italian finance

England in the Middle Ages was somewhat behind its continental neighbours in its comprehension of the detailed matters of economics. The English were neither as experienced, nor as wealthy as some other countries and the government, even though it taxed goods for export, did not have ready cash available to fund military expeditions and the like.

The Italians were accomplished bankers and were able to offer ready money to the king in the form of a loan against the taxes when the revenue became available. It was Florentine money that sponsored the early part of the Hundred Years’ War, to be paid against taxes placed on sacks of wool (and other export items).

Even kings can run up debts that cannot be paid. In 1348, Edward III became so indebted (to the tune of $3m in modern money) to Italian bankers that he was unable to pay the loan back, even when the taxes came in and consequently the financiers that had backed him were left wanting. England’s monarch was not the only defaulter at the time and some of the banks failed under the strain of unpaid debt.

Guilds

An Haberdasshere and a Carpenter,

A Webbe, a Dyer, and a Tapycer—

And they were clothed alle in o lyveree

Of a solmpne and a greet fraternitee

Prologue from the Canterbury Tales by Chaucer2

A major aspect of the wool trade was the rise of institutions called guilds. These were the formal gatherings of craftsmen (craft guilds) who participated in the same craft, for example, weaving, spinning or making gloves and merchants (mercantile guilds) who wanted to keep control of the quality and price of the goods they sold. To come together in this way, as an organised body of people with the same interest and livelihood meant that there was opportunity for conditions and pay to be regulated, to provide larger purchasing power and to build a social network which could, in theory, also provide support for those workers who found themselves in difficulties.

The interior of the Hall of Merchants Company in York.

The rise of wool-related guilds in England grew out of the increasing interest in the production of cloth itself. Carding, spinning and weaving had been practised for centuries by women in the household in order to clothe the family and make comfortable, draught reducing furnishings such as bed hangings and curtains, blankets and quilts.

Often the textiles made in these domestic situations were fairly unrefined. The people who had crafted them were doing it out of necessity and had not been trained or given the opportunities to use innovative techniques brought over from the continent. Besides which it was time consuming and had to fit in with other household chores and baby rearing. Children would grow and require new clothes, old ones would be worn out: an endless task of spinning, weaving and sewing.

The professional production of cloth was left to the men. Processing wool and making it into cloth and striving to perfect it became the focus of professional craftsmen situated in the larger towns and cities, rather than rural backwaters or villages.

Guilds were emerging as a force to be reckoned with from early in the Middle Ages. The weaver’s guild, for instance had been given Royal approval in Henry I’s reign, and was still chartered in the mid to late Twelfth Century under Henry II. It was forbidden for non guild members to ply their trade in London, Southwark or other places where London did business in the wool or cloth making industry. Business had to be conducted in the place and at the time stipulated by the guild controlling that trade. Non guild members were required to pay hefty tolls for the privilege of trading in guild towns, whereas members were exempt from these.

The Hall of Merchants Company in York.

An example of this can be found in documents relating to trade in Southampton:

And no one in the city of Southampton shall buy anything to sell again in the same city unless he is of the gild merchant or of the franchise.

Of course charters were not granted out of the goodness of the reigning king’s heart. It meant money. To receive a royal charter for a guild to practice it had to pay a yearly fee. For the weavers in Henry II’s time this was: two gold marks (1,400 silver pennies). It was not a trifling sum by any means.

Guilds were supposed to be given royal approval before setting themselves up in practice; besides giving the king an opportunity to make money from them, it gave the guild a legitimacy to have a royal charter. However, in reality, many guilds, particularly those in rural centres, away from London and the seat of power, just set themselves up without a charter.

There were distinct advantages to belonging to a guild:

- Solidarity could present before the King or to some other authoritarian body in order to have wrongs righted

- Prices for buying and selling could be regulated

- Buying power was strengthened

- Guild members enjoyed certain privileges in the manufacturing, or processing of their wool; such as in Leicester where only guild members could have their fleece washed in the town water or packed by local packers

- The guild had power to fix wages: in 1281 in Leicester it was decided that wool wrappers would be given a penny a day for labour plus food but flock pullers would get three halfpence and no food. Any guild member who was found to pay more than this would be fined by the community of Leicester

- Guild members didn’t have to pay tolls whereas non members had to

- Only guild members could sell particular produce at a retail level

- It was the guild members who made sure that middle men did not profit at the expense of the public or the guild members themselves

- Guilds offered a support network for fellow guild members when things got bad

While there was a certain amount of safety to be found in numbers being a guild member brought burdens and obligations. For a start, there was a fee to be paid in order to become a member. There were rules to be obeyed, such as a member was not allowed to go into partnership with a non member. To be a guild member meant municipal duty and members tended to become the upstanding leaders of the towns, adopting positions of power such as the mayor. As Chaucer says of his Haberdasshere, Webbe and Dyer, ‘Wel semes ech of hem a fair burgeys, to sitten in a yeldehalle on a deys’, that they were comfortably off, suggests that they were all fit to be aldermen, and that their wives would have themselves called ‘madame’ and have the train of their gowns lifted by a servant. Members of guilds were an up and coming class.

Other aspects of life became embedded in the guild traditions, which had not even the most tenuous of connections with their business. An important one was the putting on of public performances of ‘miracle’ plays with guild members strutting their thespian skills (or lack thereof, if we take Shakespeare’s’ ‘rude mechanicals’ as exemplars).

Though guilds as institutions of master craftsmanship remained for centuries (some are still around today) they did not retain the power they had enjoyed in the Middle Ages. The interest in English cloth making overtook the previous passion for exporting raw wool and the demand for cloth became so urgent that manufacturing was being undertaken by all and sundry, skilled or not.

Organisation of medieval mercantile guilds

The guilds organised themselves into sophisticated committees. The officiating member was called the alderman who was supported by a number of official staff: stewards, bailiffs, skevins, ushers, deans and chaplains.

Meetings were held regularly and the agenda for discussion would include items such as required new laws to protect their livelihood, the election of officers, and admittance of new members. Sometimes these meetings were held in conjunction with a guild feast which meant that it was not just a matter of business but also of pleasure. An example of another of the guild’s fraternal nature was the support in which it gave its members when they found themselves in trouble or if one of them had died:

If a gildsman be imprisoned in England in time of peace, the alderman, with the steward and with one of the skevins, shall go, at the cost of the gild, to procure the deliverance of the one who is in prison … If any of the brethren shall fall into poverty or misery, all the brethren are to assist him by common consent out of the chattels of the house or fraternity, or of their proper own … And when a gildsman dies, all those who are of the gild and are in the city shall attend the service for the dead, and gildsmen shall bear the body and bring it to the place of burial.3

It can be seen how the guilds were forerunners of municipal government with the offices still bearing familiar names, like alderman.

The craft guilds also regulated the apprenticeship system. One of these was that after an apprentice had served his time under a master craftsman, often a period of seven years, he was free to work at his craft under his own direction. These men were called journeymen after the French word journée meaning by the day, the term could also have come from the fact that such free craftsmen were often required to travel, journey, to different places everyday in order to secure work.

From being a journeyman, the craftsman would try to make enough money to set himself up in a set place, perhaps a shop and then take on apprentices of his own.

An apprentice at work in his master’s workshop.

Decay of the guilds

- When manufactured cloth took over from raw wool as England’s major export the demand for cloth meant that it was being made by people everywhere, particularly in rural areas where extra money was always welcome and where there was time and space to do it: spinning could be done in the main room of a cottage by candle light

- The government took over many of the guilds’ fiscal operations

- As the guilds became stripped of their duties and purpose their numbers declined

By the Sixteenth Century the power and influence of the guilds had waned to such an extent that dire measures were often taken by those remaining in them to keep them going. One idea was to amalgamate guilds, such as the guild of goldsmiths in Hull in 1598, where it is documented as including not only goldsmiths but also smiths in general, pewterers, plumbers, glaziers, painters, cutlers, and incongruously musicians, stationers, bookbinders and basket makers.

In Ipswich there were The Mercers who included such diverse crafts and trades as: mariners, shipwrights, bookbinders, printers, fishmongers, sword-setters, cooks, fletchers, arrowhead-makers, physicians, hatters, cappers, mercers, merchants, and several others. The Drapers did not merge with the tailors or even the shoemakers but joined with carpenters, publicans, freemasons, bricklayers, tilers, carriers, casket-makers, surgeons and clothiers. The Tailors aligned themselves with the cutlers, smiths, barbers, chandlers, pewterers, minstrels, peddlers, plumbers, pinners, millers, millwrights, coopers, shearmen, glaziers, turners and tinkers.

The disparity in the types of trades represented in the new guilds could perhaps be explained that they were not organised within trade related groups but rather within the town geography so that the occupants of certain streets belonged to the one guild.

In an attempt to retain some power at local government level, the guilds would appoint an alderman and a couple of wardens. Craftsmen or traders wishing to set up business in a town would be placed in a seemingly appropriate guild regardless of their occupation. By the early Seventeenth Century guilds had changed completely from their medieval forms.

Merchants of the Staple

The trade in raw wool between England and the Netherlands needed some kind of national organisation. In England this system was called the ‘staple’. Particular towns were selected, known as ‘staple’ towns, to be collection centres for wool that would then be taken to a staple port for export. The staple towns would eventually be places where exports would be registered, weighed and duly taxed before being shipped abroad, keeping the bulk of the business on home turf.

To facilitate trade at the overseas end, the government nominated a town in the Netherlands to which the goods could be sent for processing, sale and dispersal but under a watchful English eye.

From 1354, in the dozen or so staple towns in England, a Mayor of the Staple and two Constables were appointed by the merchants of the staple to oversee the king’s financial interest by way of tax collection, ensure foreign merchants were kept happy and also just for the general keeping of civil peace within in the town.

Merchants of the Staple was a trading group that formed out of the guild of merchants called ‘the Brotherhood of St. Thomas Beckett’.4 It is not known for certain when they were first founded but the earliest charter still in existence dates to 1296.

The Staple was the official body that purchased and sold raw wool. One of its purposes was to make it easier to collect tax on the goods and another was to observe the amount of trade going on. A foreign city, or collection of towns was chosen to be the place of business and all exports had to go through it and be handled by the Merchants of the Staple, appointed to the position by Royal charter.

If the Merchants of the Staple were the men involved in organising the export of wool, staple towns were the specially designated towns through which they did it and through which foreign merchants could buy and sell wool from the official traders. To trade outside this system was illegal.

The arms of the Merchants of the Staple in London.

The King to all to whom, etc., greeting. Know ye that whereas before these times divers damages and grievances in many ways have befallen the merchants of our realm, not without damage to our progenitors, sometimes Kings of England, and to us, because merchants, as well denizen as alien, buying wools and woolfells within the realm aforesaid and our power, have gone at their pleasure with the same wools and fells, to sell them, to divers places within the lands of Brabant, Flanders and Artois: We, wishing to prevent such damages and grievances and to provide as well as we may for the advantage of us and our merchants of the realm aforesaid, do will and by our council ordain, to endure for ever, that merchants denizen and alien , buying such wools and fells or cause them to be taken to a fixed staple to be ordained and assigned within any of the same lands by the mayor and community of the said merchants of our realm, and to be changed as and when they deem expedient, and not to other places in those lands in any wise.5

Organisation of the Staple [Patent Roll, 6, Edward II, p.2, m.5], 1313

However, it was never plain sailing for the Merchants of the Staple and at various times the government policy on the staples and export would change, sometimes in favour of the English merchants and at other times in favour of foreign merchants. At another stage the whole system was done away with and trade thrown open to all and sundry.

After decades of moving from city to city (even though official arguments were put to the king in 1319 for the establishment of a Home Staple), including Bruges and Antwerp, the Staple was settled at Calais in 1363. Twenty-six merchants formed the company at Calais and became known as the Company of the Staple at Calais.

Edward I was the instigator of a regulated national customs duty on exported goods, including wool and leather. Because he needed regular finance for the war against France he knew he needed a means of exacting tax from merchants on a systematic basis.

To start with, Edward I organised merchants to centralise their business dealings overseas so that export could be monitored and so that no potential taxes could slip by unnoticed.

The word staple comes from the old French word for market, staple.

In return for their diligent work for the Crown they were granted the sole right of trading in English raw wool.

It was the Merchants of the Staple who became financiers to the king, lending him funds to wage war against the French. In the first third of the Fourteenth Century the Hundred Years War began. Several factors played a part in starting the war; one was conflict over the French throne (Edward the III claimed his right to it because he was the son of the late French king’s sister), another was over control of the English Channel as a line of defence for the English, and thirdly there was the need to keep open the lucrative trade market with Flanders (as we have already seen, Flanders was under French rule which made trade with England in times of conflict difficult).

During the long series of battles the Merchants of the Staple not only continued business as usual but fought for their English King against the French. However, they were also the king’s creditors and although he might be able to rely on them to fight beside him in war, he couldn’t take them for granted when it came to asking for finance for military campaigns.

Edward, by the grace of God king of England and France and lord of Ireland, to all our sheriffs, mayors, bailiffs, ministers, and other faithful men to whom these present letters may come, greeting. Whereas good deliberation has been held with the prelates, dukes, earls, barons, knights of the shires – that is to say, one from each for the whole shire- and commons of cities and boroughs of our kingdom of England, summoned to our great council held at Westminster …, concerning damages which have been notoriously incurred by us and by the lords, as well as by the people of our kingdom of England and our lands of Wales and Ireland, because the staple of wool, leather, and wool-fells for our said kingdom and lands has been kept outside the said kingdom and lands; and also concerning the great profits that would accrue to our said kingdom and lands it the staple should be held within them and nowhere else: so, for the honour of God and the relief of our kingdom and lands aforesaid, and for the sake of avoiding the perils that otherwise may arise in times to come, by the counsel and common assent of the said prelates, dukes, earls, barons, knights, and commons aforesaid, we have ordained and established the measures hereinunder written, to wit:-

First, that the staples of wool, leather, wool-fells and lead grown or produced within our kingdom and lands aforesaid shall be perpetually held in the following places: namely, for England at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, York, Lincoln, Norwich, Westminster, Canterbury, Chichester, Winchester, Exeter, and Bristol; for Wales at Carmarthen; and for Ireland at Dublin, Waterford, cork, and Drogheda, and nowhere else …6

Excerpts from the Ordinance and Statute of the Staple (1353)

The Merchants of the Staple were able to make their way up the social ladder by acquiring lands in wool growing districts, largely in the West Country, and managing to establish distinguished families whose names are still revered.

The export of raw wool was at its height in the middle of the Fourteenth Century but over the next fifty years it began a steep decline until by 1500 or thereabouts it constituted a fraction of England’s overseas trade. The Merchants of the Staple who had held a monopoly on the export of raw wool found that their own livelihoods were under such a strain with the disappearance of the demand for their product that they could no longer keep up the civic responsibilities that they had been in the habit of maintaining. One of the casualties was the English garrison at Calais.

The Merchants of the Staple enjoyed many long years of monopoly of the wool trade in England. Members grew prosperous and often ended up with influential positions in government. It was not to last. Even after their demise as a functioning business group, the Merchants of the Staple still exist.

Hanseatic League

Across the Channel, Europe was developing its own guilds and trading laws commensurate with the craft guilds of England and particularly the Merchants of the Staple. It is thought to have originated in the town of Lübeck in Northern Germany after 1159. The term Hansa was first documented in 1267 but the organisation was already well established by then. Members of the Hansa tried to improve trade conditions for themselves and were successful in getting Henry II to lift trade embargos and fees so they could trade throughout England without restraint. Henry’s compliance did not please the English traders.

Flemish traders who bought and sold goods with England also organised themselves into a formal group: the Flemish Hanse of London. The rules under which the league worked were similar to those of the Merchants of the Staple and forbade trade by non members except under special licence or through paying tolls.

The German Hanse consisted of traders from the towns of Lübeck, Hamburg, Bremen, Dantzig, and Brunswick as well as up to 80 more unspecified ones. These Hanse cities had bargained with the English government for all sorts of special trade privileges and concessions.

Not only did the Hanse end up trading under the same terms and conditions in England as the English merchants, they were even more privileged outside of England. This meant that they were able to offer much more competitive prices to potential customers than the English.

While the English merchants were busy petitioning their king to get tough on foreign merchants in England, the town of Hamburg was doing a similar thing to the Merchant Adventurers. The English tried to establish a base, first in Emden, then Hamburg and then Emden again. The second attempt at Emden, in 1579, proved successful although the Hanseatic League tried to have the Count of East Friesland expel them. The Merchant Adventurers used Emden as their European staple until 1587. Surprisingly, in 1586, the Senate of Hamburg issued an invitation back to Hamburg but it did not eventuate until much later. By 1611 the staple was established in Hamburg.

The Hanseatic League suffered its own decline and by the late Sixteenth Century was in deep distress through its inability to deal with organisational issues as well as the political and international trade changes that were happening. The Hanse’s last formal meeting was held in 1669, which only nine members attended. The Hanse struggled to survive in to the Nineteenth Century, just as its English counterparts the Merchants of the Staple and the Merchant Adventurers, but had become not much more than a social club.

Wool in the Time of Chaucer

A Marchant was ther with forked berd,

In mottelee, and hye on horse he sat;

Upon his heed a Flaunderyssh bever hat7

Prologue from The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer

At the beginning of the Fourteenth Century raw wool was still the major export product of England. Everybody was raising sheep, from peasants with a single animal to large landholders with hundreds of them. Wool exports in the early years of the century amounted to 30,000 sacks a year. Cloth was also exported but was a marginal industry; 5,000 pieces of cloth was a sixth of the raw wool export.

The English were producing cloth for their own use, though still importing the finished fabric back from Flanders. The home-made, coarse textile was made for many years to come but the guilds in the towns were working hard to refine their techniques to make a fabric comparable to the Flemish. Even before the start of the Hundred Years War, Stamford cloth was renowned for its fineness as far away as Venice.

In the Fourteenth Century the industry changed, slowly but surely. The guilds had monopolised the manufacture of cloth and they had made it into an art form for which one had to be apprenticed for a set term in order to learn all there was to know about spinning and weaving. The making of cloth itself, rather than the growing of wool, was on the rise and people everywhere were beginning to take it up, just as they had embraced the raising of sheep. To be sure, quality suffered because the guilds were no longer the major producers. Any peasant in the middle of nowhere could spin a bit of extra thread and the merchants found that the cost was a lot less than when manufactured by master craftsman, therefore profit could be larger.

Edwards I and II oversaw action that banned the import of finished cloth into England. This meant Flanders no longer had a ready market to sell their cloth to. Craftsmen from abroad were brought to England to teach the native population their innovative techniques and trade secrets. English craftsmen strongly resented the intrusion by the foreigners, at the crown’s expense and request; it could be seen as nothing but insulting. The visiting craftsmen were given government protection from attacks by the outraged Englishmen.

During the century the manufacture and export of finished cloth continued to grow. Broadcloth was a popular, densely woven woollen fabric which was made on a broad loom (the width measuring 1.75 yards) was made from the short staples of wool and ‘fulled’ after weaving. ‘Fulling’ was a process where water, heat and agitation made the fibres, creep and shrink (felting) to make strong, smooth fabric. The export of this cloth over several generations in the Fourteenth Century multiplied nine-fold. And, correspondingly, the export in raw wool declined. The peak of the raw wool export industry was the mid Fourteenth Century.

Different areas of England were becoming specialised in certain aspects of wool growing and manufacture. For instance: The West Country, the

Spinning and weaving.

Pennines in Yorkshire, and the countryside of Lancashire had plenty of luscious pasture for farming sheep, soft water for washing, dyeing and scouring fleece, and running streams which would later supply water power for driving fulling mills.

In Norfolk and its surrounding areas in East Anglia, the sheep grew a long, fine fleece which was made into worsted cloth, named after the village of the same name in Norfolk.

The Merchants of the Staple, who had monopolised the industry so well, also faded into the background as their market fell away; with England using more of its own raw material and making it into a new export product. With less trade they made less money and had less power. They were also less able to perform their municipal duties; such as providing the means for maintain the defence force at Calais.

Increase in exports meant an increase in demand for goods to sell which in turn meant that a highly organised production line was the only realistic way of meeting the demand. This could not be done by the guilds; their system did not encompass the whole process from start to finish but only the crafting of a particular section in it. The need for a general overseer saw the rise of a new kind of merchant, the entrepreneur, the person who linked all the manufacturing steps into a seamless production line. It was he, aided by financial backing, that would make sure wool would get from one stage to the next on time so that orders from afar could be filled and the money roll in.

Wool in Tudor times

The next step in the history of the English cloth trade was an enormous one and it meant that England remained prosperous for centuries. It did, however, also mean the decline of the craft guild. Towns as centres of production were no longer important; much of the cloth making, in its various stages was done in the country in small villages or by rural people.

It was a great opportunity for the poor of the land:

- They could do as much or as little as they could

- They didn’t need their own equipment

- Inclement weather meant that there was an opportunity to still make money

- The whole family could help

- Skill was not of the greatest importance

To have the workers working in their own homes like this was the start of what was known as the Domestic System and continued for a long time. Of course, there were as many disadvantages to the system as there were advantages:

- Workers were not independent and relied on the business owners

- Tools had to be hired from the business owner and paid for out of the money made from producing the cloth

- There was no negotiation about prices or conditions

- There was often the possibility that the worker ended up owing more money to the owner than he made

As someone who probably already worked for a landowner these disadvantages would have been nothing new in the experience of the poor. Any work was better than no work.

Extra tax had been added to the export of raw wool in order to encourage the making of finished cloth. By 1420 cloth exports had overtaken those of raw wool: during the 50 years be tween 1350 and 1400, cloth exports multiplied eight-fold to an average of 40,000 pieces a year. Ninety years later this figure itself had quadrupled to 160,000 pieces of finished cloth. Despite the large amount of material going overseas it appears the home market utilised two or three times that.

The cloth industry in England was well established by the end of the Fifteenth Century and would remain its dominant industry until the appearance of cotton in the Eighteenth Century.

Monopolies still existed over the trading of cloth, just as it had done over raw wool; the type of merchant and how he traded changed.

The North Sea became a difficult place to trade with strong opposition from the German Hanse. The Hundred Years War, although long ended had left ongoing problems from the direction of France. This all meant that the Netherlands was the only real option for entering European markets.

The demand for raw wool to be turned into undressed cloth meant that every available piece of land was turned to the raising of sheep, or so the popular theory goes. There is some dispute as to the real cost of sheep versus land for general agriculture. The enclosure of land for sheep was thought to have contributed to a national food shortage, a large body of unemployed rural populous and displaced persons.

The kings of England were still using revenue from wool and cloth export taxes to pay for war against European neighbours.

Henry VIII, and his rejection of the Pope and Catholicism, undertook a massive task in the dissolution of the monasteries. This meant important opportunities for those with money or influence with the king. The monastery at Cirencester had two newly built fulling mills, which the former abbot had ordered at a cost of £500 or more. Such a set up as this was in effect a prototype of the factory; offering a variety of potential processes to be done under the one roof, or at least on the one property.

Enclosure, legislated in 1487, was another topical issue for the people of Henry VIII’s time. The cloth trade was again putting pressure on England to increase its product and in order to do so more sheep needed to be farmed for wool. Land that had been traditionally used for crops was marked out for pasture. Food became scarce and prices skyrocketed. Another disastrous consequence was the displacement of agricultural workers whose services in ploughing, harvesting and processing food were no longer in demand. As is the way, those that got the money were the great landowners and merchants.

Like his predecessors, Henry VIII was an expensive war monger; borrowing heavily from foreign financiers to fund his was chests. It consequently led to a debasement of the English currency which meant that English wool and cloth were once more very attractive imports for foreign merchants.

At the time of Henry VIII’s demise England was exporting twice as much cloth than when he had ascended the throne. While the increases in exports might look like prosperity, the proceeds from industry generated tax went back into the war coffers or to its financial backers.

Weaver makes good

Men of influence tended to come from the merchant class or the aristocracy but John Winchcombe, known as Jack Newberry in Delony’s ballad of 1597, was neither. He had been a humble weaver whose first step to success was to marry the widow of his former master. His business interests never looked back and when he died in 1520 he was extremely rich. His son, John Winchombe II, furthered his father’s meteoric social rise by becoming a Member of Parliament.

The Merchant Adventurers of London

The term Merchant Adventurer is undoubtedly romantic and not necessarily a misnomer in this case. There were merchants who would sail the seas in search of goods to buy and of ports in which to sell English merchandise. They were indeed referred to as ‘adventurers’, ‘venturers’ or ‘merchant adventurers’. The term loosened over time to include the meanings of financial venture, as in economical risk taking rather than physical risk taking.

The hall of the Merchant Adventurers in Bruges.

In the early days of the company the Merchant Adventurers mainly exported plain broadcloth (a dense, woollen cloth that was fulled after being woven) and imported all sorts of exotic and luxury goods to England. In its early days it was based at Antwerp in the Netherlands and was able to sell cloth to other Dutch towns as well as to Flemish markets. The company was made up of separate but associated groups, mostly from non London towns including York, Norwich, Exeter, and Hull.

As time went on the fellowship’s aims grew similar to those of the Merchants of the Staple before them, that was; to build a monopoly of the trade by making it illegal for anyone to trade without complying with the Adventurers conditions. It was decided to make it harder to become a member. In order to become one you had to either be an apprentice, inherit from your father, or purchase a membership. These conditions did much to ensure that the Adventurers were largely a London based organisation made up of London traders. To be an apprentice to a member or to inherit a position meant residing in London. Traders from other towns and cities in England were welcome to purchase a membership but there were exorbitant fees involved, which were, of course, designed to limit outsiders from the city.

As with the Merchants of the Staple different kings of England put forward different trading rules; some favoured the English merchants, others favoured those from overseas. Also, the bases from which the traders could sell changed continuously; sometimes they were based in England and sometimes abroad.

The Fifteenth Century saw the Adventurers rise as a major rival to the Merchants of the Staple. In 1486 the city of London authorities publically recognised them as a legitimate company and the group became the Fellowship of the Merchant Adventurers of London. They had been formed as a commercial body long before this time and as early as the mid Fourteenth Century they were giving the Staples a run for their money.

The Adventurers enjoyed similar privileges to those of the Merchants of the Staple. They had a base overseas, enjoyed government backing, power and wealth. To become a member of this elite establishment the trader had to pay the exorbitant sum of £20. In 1497, through an act of parliament the fee was dropped to a more manageable £6 13s. 4d.

In 1498 the Merchant Adventurers were distinguished with their own coat of arms. Sixty-six years later they became known as The Merchant Adventurers of England, granted by royal charter. In power and wealth they outstripped the Merchants of the Staple, who had kept their trading interests to the export of raw wool and so limited their potential as financial entrepreneurs.

They carried on the tradition of merchants offering other services to the king, such as providing men to fight on his behalf. Where the Staplers had offered to provide up to a hundred men at arms, the Merchant Adventurers were supposed to have sent two thirds of the ships that made up the battle fleet that would face the Spanish Armada.

The Merchant Adventurers were advocates of exporting only undressed cloth, that is, cloth that is woven but not dyed or finished in any other way. In 1514 the company put forth series of arguments for this.8 And it was for exactly the opposite reason that a patent roll was issued in 1616 – 17 to establish a company that would export in dressed cloth because the Merchant Adventurers would not.

James by the Grace of God, etc.:

We have often and in divers manners express ourselves … what an earnest desire and constant resolution we have that, as the reducing of wools into clothing was an act of our noble progenitor King Edward the Third, so the reducing of the trade of white cloths, which is but an imperfect thing towards the wealth and good of this our kingdom, unto the trade of dyed and dressed, might be the work of our time.

To which purpose we did first invite the ancient company of Merchant Adventurers to undertake the same, who upon allegation or pretence of impossibility refused.9

The Merchant Adventurers enjoyed a long reign as supreme traders but in the Seventeenth Century they lost their trading privileges following the Glorious Revolution of 1688 (and the overthrow of James II). Parliament opened trade to everyone and the Adventurers, though seriously declining as a trading company, existed into the Nineteenth Century.

Friction between the Staples and the Adventurers

As England became more of a cloth manufacturer and less of an exporter of raw wool, tensions between the two great merchant companies grew in intensity. In 1504 a judgement was made by King and Council in the ‘Sterre Chambre’ concerning:

… certain disputes between the said merchant adventurers and the merchants of the staple of Calais, whereby wither party making any use of the privileges of the other, should be subject to all regulations and penalties by which the other is bound.10

The decline of the Staples and the rise of the Merchant Adventurers is well illustrated in the following poem by William Forrest in the time of Edward VI. It demonstrates how the Staples, relying on the sale of raw wool, had been steadily finding their countrymen turning to making cloth for export and using the raw wool for their own cloth manufacture. The Merchant Adventurers were all set to exploit this new industry and export the woven textile instead of the fleece.

No town in England, village or borough

But thus with clothing be occupied.

Though not in each place clothing clean thorough,

But as the town is, their part is applied.

Here spinners, here weavers, there clothes to be dyed,

With fullers and shearers as be though best,

As the clothier may have his cloth drest.

The wool the Staplers do gather and pack

Out of the Royalme to countries foreign,

Be it revoked and stayed aback,

That our clothiers the same may retain,

All kinds of work folks here to ordain,

Upon the same exercise their feat

By tucking, carding, spinning and to beat.11

The Domestic System

At the end of the Middle Ages, as raw wool was gradually being replaced by woven cloth as a major export, the domestic system of manufacture was a new and radical system that eventually saw the decline of the guild system. People were able to produce spun yarn and woven cloth in their own homes, earning themselves a little extra money.

While there had always been a percentage of workers producing goods for sale outside the guild system, by the end of the Fifteenth Century it was becoming an increasing trend. A new type of merchant had emerged, known as ‘clothiers’, or ‘merchant clothiers’ who were buying wool, not for export, but to have made up as cloth, which they would then export. It was these merchants who were responsible for the rise of the new domestic system of manufacture. They required the work to be done within certain time frames and therefore arranged the collection from one set of workers and delivery to the next to ensure a seamless flow of production. It meant that master craftsmen no longer had control over the market; they couldn’t regulate costs, conditions or quality and quite often it was not of a very good standard. Those who undertook work offered by the clothiers were paid in the form of wages.

A household working in the domestic system.

Placing themselves outside the reputable craft towns meant that the guilds were not in a position to interfere with the new system either. A law made in 1495 saw that authorities were unable to use their power to clamp down on non-guild member activities of manufacture.

The towns that had made a name for themselves as centres of craftsmanship lost their monopoly on the trade and consequently found their previous posterity on the downward slope. Taxes could not be paid and building projects often had to remain unfinished. While the clothiers became wealthy and non guild workers enjoyed some extra wages the urban areas suffered an economic crisis.

As we have seen, England had never been up to the same standard of manufacture of woollen cloth as their Flemish counterparts. To improve the skills needed to upgrade their product, England welcomed the knowledge and techniques brought to them by foreigners. Religious persecution of Protestants in various parts of Europe saw many refugees fleeing to Britain. Many of these immigrants were textile workers and were more than happy to begin plying their trade in England and passing on their skills to the local population.

At first the newcomers were strongly resented and were only supported by the royal authority. However, with time they settled in and as they became immersed in their business and shared their expertise with their new neighbours they were accepted. Not only did they bring technical skill with them, the refugees brought inventions that would eventually revolutionise the cloth industry. In Queen Elizabeth I’s time the ‘stocking frame’ was invented, although it did not fulfil its potential for another hundred years or so.

The domestic system of cloth manufacture grew steadily for the next couple of centuries until it, like its guild worker predecessors, suffered through a new type of manufacture in the rise of the mechanised factory.

Wool in Nineteenth Century

Evidence of Mr. James Ellis, 18 April, 1806 (a clothier of Harmley, near Leeds, working with an apprentice, two hired journeymen and a boy, and giving some work out)

Do you instruct this apprentice in the different branches of the trade?

As far as he has been capable I have done.

Will you enumerate the different branches of the trade which you yourself learnt, and in which you instruct your apprentice?

I learnt to be a spinner before I went apprentice; my apprentice was only eleven years old when I took him; when I went apprentice I was a strong boy, and I was put to weaving first; I never was employed in bobbin winding myself while I was apprentice; I had learnt part of the business with my father-in-law before I went; I knew how to wind bobbins and to warp; after that I learnt to weave; we had two apprentices, and after I had been there a little while we used to spin and weave our webs; while one was spinning the other was weaving.

An engraving of Hogarth’s The Lazy Apprentice.

Did you also learn to buy your own wool?

Yes; I had the prospect of being a master when I came out of my time, and therefore my master took care I should learn that.

Does that branch require great skill?

Yes it does; I found myself very deficient when I was loose.

Different sorts of wool are applicable to different dyes and different manufactures?

Yes. I was frequently obliged to resort to my master for information as to the dyeing and buying of wool.

Does it not require great skill to dye according to pattern even when you have bought wool?

Yes.

Were you also instructed in that?

Yes; I kept an account all the time I was apprentice of the principal part of the colours we dyed, and practised dyeing: I always assisted in dyeing; I was not kept constantly to weaving and spinning; my master fitted me rather for a master than a journeyman.

And you instruct your apprentice in the same line?

Yes; we think is a scandal when an apprentice is loose if he is not fit for his business; we take pride in their being fit for their business, and we teach them all they will take.12

The Old Apprenticeship System in the Woollen Industry [Report of Committee on the Woollen Industry, 1806 (III), p.5, 1806]13

Wool in the Twentieth Century

The Merchants of the Staple, the Merchant Adventurers, and craft guilds may, or may not, still exist in some form today but long gone is their power and control over the wool export industry.

The wool industry in the Twentieth Century was given the name The International Wool Textile Organization (IWTO) which also went by the name of the Federation Laniere Internationale (FLI) and it formed out of groups of industry workers. It was initiated in 1928 as an international arbitration body for the wool trade in its various processes. Its purpose has since grown to include the regularising of weights and measures used, to facilitate trade between member countries, to collect statistics and other information, and to support research for many aspects of the industry. The organisation is much more focused on the wool trade with the extra activities that grew from the Merchant groups like civil duties and the putting on of miracle plays are within the reserve of the individual as non-work related practice.

Wool in Australia

In 1788, when the first fleet landed on the shores of the new British colony of Australia, it carried not only convicts and their gaolers but also the first sheep to step onto that land. They were not taken there for their wool but for their meat.

Map of Australia.

Not long after Spanish Merinos were imported and 1796 saw the start of what was to be another long and prosperous industry. These first immigrants were joined by other wool producing sheep from Britain, Europe, and even the USA (Rambouillet and Vermont breeds).

The first samples of commercially viable wool were sent to England in 1801 and the first bale ever to be auctioned of Australian wool was in 1806. From then until about 1870 England was the main consumer of Australian wool; its mills were still churning out yards of woollen cloth. And in response to the demand, Australia began to breed sheep in earnest, just as England had done centuries before.

The main type of wool grown in Australia was Merino. It was graded into three categories: superfine, fine and medium according to the length and fineness of the fibres. And just as in early England, different sheep thrived in different conditions producing different types of wool, so did they in Australia. The superfine Merino wool preferred the colder and wetter climates of NSW, Victoria and Tasmania whereas the dry, harsh landscape of South Australia required a tougher sheep that consequently bore coarser wool.

Wool was transported long distance in bales, apparently invented so that a bale could sit comfortably either side of a camel’s hump. They were enormous things, twelve of them weighed about two tonnes. They were not just carried by single animals however, but more often by teams of bullocks pulling large, cumbersome wagons.

Toward the very end of the Nineteenth Century Australia’s wool exports moved primarily from England to Europe itself. The mills of England were no longer producing the wool cloth it had been so famous for.

Shearing sheep

Before wool was taken from the live sheep, the hair (similar to goat hair) covered hides would have been used to make clothes, blankets, foot wear and rugs. As the sheep developed wool they would leave lumps of it behind during the moulting season. It was gathered, teased into lengths and twisted into a primitive yarn.

From gathering naturally shed fleece humans devised ways of harvesting wool in larger batches at a time more suited to them than nature had devised. It started with plucking by hand and combing with bone and bronze implements to cutting away from the skin with knives. Shears have been found that are over three thousand years old. Up until the age of electricity hand shears, like large scissors, were used to shear a sheep. Now they are given a ‘number 1or 2’ haircut with an industrial set of electric razors similar to those a barber uses.

A pair of traditional shears.

The fleece is sheared from the skin of the sheep, a job that has become an art form. It takes dexterity to negotiate the bends and folds of an animal with four legs even with modern technology. The fleece is removed as a whole, unbroken coat.

The coat is picked up and thrown onto a table for the wool classer to skirt it (trimming away the outer edges of the fleece to leave the longer, better quality). The classer categorises the fleece according to colour and fibre length and strength.

With the fleece sorted into bins of similar quality it is then taken and pressed into a bale of wool. One bale comprises about 40 fleeces and weighs up to 200 kg. This wool is unprocessed, that is, it has not been washed or had any of the lanolin (the fleece’s natural oil) removed, it is known as greasy wool.

The cleaning process is called scouring and involves washing the fleece to remove, not only dirt and extraneous bits and pieces (twigs, grass seeds etc) but also the lanolin which is separated from the rubbish and made into cosmetic creams such as hand moisturisers. The clean wool is then ready for further processing: combing, carding and spinning.

Worsted processing

Worsted processing uses only virgin wool, that is, unused in anyway previously (some wool is reprocessed after an initial spinning meaning that it not virgin wool). The staples need to be long and fine and scoured to remove any impurities and oil. Any short fibres will be discarded to be reused in a different process. One of the main features in worsted yarns is the fact that the fibres are combed carefully so they lie parallel to each other as much as possible. The fibre is spun into a tight twist.

Worsted wool is a classic textile for making men’s suits.

A tailor’s sample book of worsted fabrics.

A tailor’s sample book of worsted fabrics.

Wool processing

All sorts of wool fibre can be used in the woollen process, even fabric. It will be broken down into fibre before being mixed with other sorts of wool, greasy, scoured, short fibres etc. This means that waste from worsted wool spinning can be used.

Some of the major sheep wool types

There are many more different breeds of sheep than mentioned here but this list comprises the most commonly used ones for wool:

- Blackface – coarse mountain wool

- Bulky low lustre wool

- Cheviot

- Coopworth – coarse long lustre wool

- Corridale – medium fine wool

- Hampshire-short bulky wool and meat

- Leicester – long lustre wool

- Lincoln – long lustre wool

- Merino – fine wool

- Perendale – Long, bulky

- Polwarth – medium fine wool and meat

- Romney – long lustre wool and meat

- Suffolk – short bulky wool and meat

Parasites and other problems

Sheep may be fairly hardy and can live happily in the pastures without too much human intervention; however, there are several problems that can interfere with a sheep’s health and well being.

- Common parasites that can infest sheep are: intestinal worms, maggots and lice. Worms can be controlled through good farm management, prevention rather than cure. The grazing paddocks need to be in good shape, not overstocked or bare of grass. Then drenching can be applied once or twice a year. Drenching is a liquid worm medicine squirted into the sheep’s mouth. A narrow race is filled with sheep so each can be given its dose and then let out the other end

- Lice are a problem for sheep just as they are for humans. To control the breeding sheep are back-lined (in which the chemical is applied along the backbone) or put through a long trough full of the chemical, this is called dipping

- In Australia sheep can suffer from maggot infestation caused by the larvae of the blowfly. The site of the infestation is usually around the backend where wool gets soaked with urine. Removing the tails of lambs has been a traditional way of helping solve this problem but ethical questions are being raised about the methods used to do this (without anaesthetic). An additional measure is to crutch the sheep before the wool gets too dirty and attractive to flies. This is a quick shearing around the bottom. At the other end, wool can grow too long over a sheep’s eyes so they can’t see. They are sometimes given a hair cut in a process called wigging

- Footrot is a highly infectious disease which can stay in the ground for a week or more. It cripples the animal. Infected sheep are given a toe nail clip and walked or stood in a chemical bath. If the infection is too bad the sheep are sent to the abattoir to be used as meat

- In medieval times sheep poo was an important fertiliser for crops and just as useful a product as the animals’ meat and wool

- When Richard the Lionheart was held for ransom, certain religious orders who were wool growers were able to contribute to the release money through paying taxes in wool

- A decree was issued in 827 that women were to shear the sheep

- William the Conqueror took English textiles back to France with him where it was widely admired for its high quality

- Policy on foreign merchants during the early part of the Fourteenth Century was that they were only supposed to stay in the area for 40 days for the purpose of conducting trade, and furthermore, that they should stay with a native merchant who could watch they didn’t get up to mischief. They were not allowed to stay in an inn

- Henry II, in 1163, gave the weavers of York the right to have their own guild. For £10 a year they had the sole right to weaving and dyeing striped cloth. This was paid dutifully for about 40 years but in the very early years of the Thirteenth Century the guild’s ability to pay its dues declined until they were not only totally unable to pay their annual subscription but where several years in arrears (by 1309 the weavers’ guild of York owed the King £780)

- In 1180 Henry II, probably inspired by the success of the London weavers’ guild and their annual contribution to his coffers, tried to seek out all unregistered guilds and fine them. He managed to track down the saddlers’ guild in York and they had to pay a sum of 20 shillings; the guild of glove makers had to pay 2 marks, the same as the weavers in London paid for their annual charter, and a guild of hosiers had to pay 1 mark

- The guild of weavers forbade the weaving of cloth at night because candles were insufficient to see well by in order to produce top quality cloth

- The weavers’ guild became a powerful force in London in the Middle Ages and at one point the city administrative centre tried, with bribery, to get the king to get rid of it. No action was taken, the bribe never materialised for one thing and the weavers increased their fee to 1,600 silver pennies a year instead. The king could hardly turn away from such a secure source of revenue.

- Astronauts wear wool when in space

- Wool is an ideal insulator, protecting from heat, cold and sound. This is because the crimp of the fibres adds bulk to the textile which traps air

- Wool absorbs moisture well. It can absorb approximately one third of its own weight

- Wool bearing animals were being domesticated and the processes for spinning and weaving it were developing in South America at a similar time to the developments on the other side of the world. The animals were not sheep but llamas and alpacas whose closest relatives are those of the camel family

- The wool industry was of such importance to England that the wool sack became the symbolic seat for the Chancellor. There were four of them to start with, large red bags of wool, probably introduced in Edward III’s reign to symbolise England’s major export

- Wool is used as a low fire risk fibre. It needs a higher temperature to make it ignite and the rate of spreading is relatively slow compared to other common fabrics. It will not melt, drip or let off toxic gases when alight. A woollen blanket is a good thing to wrap a burning body in to stifle the flames

- Jackie Howe was an Australian shearer who, in 1892, managed to shear an incredible 321 sheep in a day

- Lucius Columalla was a Roman living in Spain. He is supposed to have first crossed the native Spanish sheep with the Roman Tarrentine and come up with the Merino

- ‘Morrowspeches’ was the name given to guild meetings in which members might be disciplined or fined or to have grievances aired

- In 1350, in London there were more than 40 craft guilds operating

- The word ‘sterling’ as in pounds sterling, originally came from the word ‘Easterling’ which was used to name the traders from Germany and the Netherlands

- One suggested etymology for the word blanket is that the article, made of wool, was invented by a Thomas Blanket in the Fourteenth Century. This turned out to be a humorous suggestion made by a Nineteenth Century Canadian author of fiction

- A parliamentary act of 1666 and 1678 forbade the burial of a corpse in any garment or shroud unless it was made of wool; also the coffin was to be lined with wool. This was yet another effort by the English government to boost its industry. By 1814 so many people had disobeyed the law that it was repealed

- Pope, in his Moral Essays, Ep. I, iii (1733),has a funny take on this:

‘Odious! In woollen! ’twould a saint provoke!’

(were the last words Narcissa spoke).

‘No! Let a charming chintz and Brussels lace

Wrap my cold limbs, and shade my lifeless face.

Notes

Sources of English constitutional History, (eds) Carl Stephensen and Frederick George Marcham, Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York and London, 1937, pp. 193 – 4.

The Riverside Chaucer, (ed.) Larry D. Benson, Oxford University Press, third edition, 1988.

Cheney, Edward Potts, An Introduction to the Industrial and Social History of England, Project Gutenburg, 2007, Chapter III: Town Life and Organisation.

From A History of Commerce.

English Economic History, pp. 178 – 8.

Taken from: Stephenson, Carl and Marcham, Frederick George, Sources of English Constitutional History, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York and London, 1937. pp. 228 – 229.

The Riverside Chaucer , (ed.) Larry D. Benson, Oxford University Press, third edition, 1988.

See English Economic history, pp. 402 – 404.

English Economic History, p. 454.

Tanner, J.R. (ed.), Tudor Constitutional Documents AD 1485 – 1603, Cambridge university Press, Cambridge, 1951, p. 260.

Trevelyan, G.M. Illustrated English Social History vol. I, Longmans, Green and Co, London, 1958, p. 129.

English Economic History, pp. 499 – 500.

From English economic History (eds.) Bland, Brown and Tawney, G. Bell and sons Ltd, London, p. 499.