CHAPTER TWELVE

The Industrial Revolution

Before the revolution

The raising of sheep for wool and the export of it had been one of early

England’s major economic staples. By the time of Henry VIII the sale of raw wool overseas had been well and truly overtaken by the manufacture of woollen cloth.

The rise of the newer industry meant that people all over England and particularly in rural areas participated in the various processes that turned raw wool into cloth. This was known as the domestic system and it suited the people of England very well. One did not have to be highly trained in order to do some of the jobs required. One could keep a sheep and sell its wool, and spin thread in the evenings after all the other day’s chores were done. Weaving too could be done in the largest room of a cottage.

While this system worked well for centuries it began to fail with the advent of labour saving machinery.

For several centuries the industry of making cloth had been carried out under what was known as the ‘domestic system’, where people undertook work such as spinning yarn or weaving cloth in their own homes, often to supplement other income. While there had been town-based craftsmen for a long time, and once the guild members had dominated the work force, the domestic system meant that the output of work was no longer tied to urban areas. What then happened was particular crafts tended to proliferate in a particular rural area. Subsequently new centres emerged just as they had done in the time of the guilds.

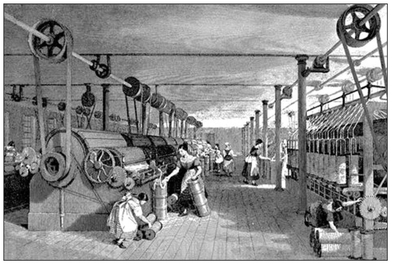

Cotton factory, Manchester.

Birmingham, Halifax, Leeds and Manchester were leading lights of the domestic system of textile production, opening the way for the introduction of the factory-based manufacturing system. The centres often appeared as specialists in one or two areas of manufacture (e.g. fulling, spinning or weaving) because geographical attributes of that area were fundamental to the processes used in those processes. Fulling required running water to power the mills (already in operation in medieval times). Easily accessible water was also good for washing cloth and dyeing it.

Before the introduction of cotton as a raw material, wool and woollen cloth were the staple products of the textile industry in England. Spinning was done on spinning wheels powered by a foot treadle and looms were all hand operated as were knitting frames.

The Beginning of Mechanisation

The fulling mill was the first real non-human powered machine and it had been around for centuries. The mills were similar in construct to mills that gound wheat or corn into flour only they turned giant hammers to batter rolls of felt rather than large stones to grind grain.

The first real water powered textile factory was that built by Thomas Lombe in 1719 on the River Derwent in Derby. The secret behind this water driven mill for spinning organzine silk thread was stolen by Thomas’s brother John from an Italian mill. John infiltrated the mill in disguise and took detailed notes of the structure and how it worked to take back to his brother in England. Unfortunately John did not live long enough to enjoy the stolen fruit of his labour because, legend has it, an Italian woman tracked him down and poisoned him.

Cotton, introduced to England by the East India Company, had given fashionable beings a taste for the light and elegant material. So much so that England began producing its own calico and lawn, and in the early part of the Eighteenth Century it was forbidden by law to print imported cotton cloth in the interests of the home product. Imported linen was exempt from this edict.

The manufacture of cotton and silk were relative newcomers to England’s textile industry in the Eighteenth Century and they were successful. They did not oust the old woollen cloth merchandise and the demand for these continued to grow, slowly but steadily.

The increased demand for English goods from foreign countries meant that the organisation needed to meet the demand was no longer adequate, just as it had happened when England began making and exporting woven wool fabric instead of staying with the tried and true raw wool. Making cloth by hand was no longer a viable indsutry, people could not physically work hard and long enough to produce the volume wanted. Machinery, however, could. Techonology was advancing in great leaps and bounds in the Eighteenth Century and it is these inventions that played a major role in the Industrial Revolution.

Spinning was one of the most labour intensive steps. It was being done in a manner that had changed little for thousands of years. The drop spindle, while no longer a common tool, was still around and it was inevitably the implement used by the very poor to eke out a meagre existence. The spinning wheel in its various forms, in particular the great wheel, was the normal method of spinning. It was quicker than the ancient drop spindle but even so, one weaver could use the yarn made by five or six spinners in the same time frame.

Unfortunately it was an invention to facilitate weaving that came before one for spinning and so the weaver was soon able to far outstrip the production of the spinner. In 1738 John Kay invented the flying shuttle. Instead of thrusting the shuttle by hand through the lifted warp threads it could be manipulated by a system of pulleys and two cords. This was even more beneficial to weavers of broadcloth who required two men to operate the hand loom; one to thrust the shuttle through the uplifted warp threads and another to retrieve it at the other end and send it back again. Kay’s flying shuttle meant that broadcloth could be woven by a single man.

Now the problem of needing more spun yarn was exacerbated. Weaving could be done in a fraction of the time it had been traditionally but the yarn was not available to enable it to be done. The Royal Society decided to launch a competition with a monetary prize for anyone who could complement the flying shuttle invention with one that would increase the speed of spinning yarn. Whist nobody claimed the prize it set in motion the steps necessary to make a more time efficient industry. One of the first successful attempts to make a spinning machine was James Hargreaves.

The Major Inventors

James Hargreaves

James Hargreaves, born in Lancashire, and was a carpenter and weaver until he turned to inventing in 1740. He began his new career as an inventor with a commission to make a more efficient carding machine. His innovative spinning jenny did not arrive on the scene until 1764. The story behind the invention was that he startled his wife who had been working at the great wheel; she jumped up in surprise and knocked it over. James observed that the wheel and the spindle were still going. He thought that if one could put several vertically placed spindles next to each other then it could be possible to spin more than one thread at a time from the one wheel.

His idea was that the one great wheel would make the spindle revolve via the means of a leather band made into a continuous circle. A pair of bars would replace the human hands that drew the carded wool from the distaff and guided it to the spindle with a pair of bars which could be consecutively separated and closed, moved closer or further away from the spindles on wheels, and so manage to spin several threads at the one time. It was named in honour of his wife.

The local community saw the machine as suspicious and were afraid that it would put them out of work. In 1768 Hargreaves’ house was set on fire and everything within it was burned including the spinning jenny. Hargreaves left the district and set up a cotton mill in Nottingham with Thomas James. Hargreaves’ invention spawned many similar ones and there were machines that could spin 20 or 30 threads at a time.

Richard Arkwright

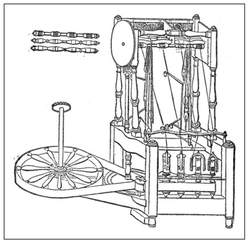

Richard Arkwright was not aiming to copy Hargreaves’s jenny but was engaged in trying to invent a more efficient one altogether. He had looked at the experiments of Wyatt from Northampton for inspiration. Arkwright worked on a succession of rollers through which the carded fleece was fed. Each pair of rollers spun more quickly to the effect that the fleece was teased out to a fine amount, just as an expert human hand might. The patent for this spinning machine was taken out in 1769 and made a strong rival for Hargreaves’ jenny.

Arkwright didn’t stop with the patented design but worked on it for years afterwards. He made and sold the machines himself and with various business partners in different districts. The patent was eventually revoked, the argument being that it contained not enough original material but relied too much on that of predecessors like Wyatt. The outcome was that with the patent lifted the invention was open to manufacture by anyone who had the means or the money. Spinning machines invaded industry. Despite the loss of his patent, Arkwright managed to amass a healthy fortune for his spinning machine and was publicly acknowledged for his services to the industry and received a knighthood in 1786.

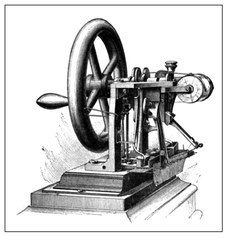

Arkwright’s Spinning machine.

Samuel Crompton

Hargreaves had sparked an inventing frenzy and after Arkwright came Samuel Crompton, another weaver by trade. He took the best aspects of Hargreaves’s jenny and Arkwright’s spinner and in 1779 he formed a hybrid that became known as the spinning ‘mule’. Crompton did not patent his improved invention and it became a popular device for spinning thread.

Just as the flying shuttle spurred on the invention of a faster and better spinning device, so the spinning jenny and mule sparked the search for a carding and a combing machine so that the fleece, ready for spinning, could be at hand. A carding cylinder was already in existence, having been invented by Paul in 1748. It now came into its own and was soon joined by wool-combing machines in 1792 and 1793.

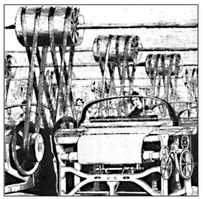

Edward Cartwright

The process began to turn full circle. Now that spinning and fleece processing had been made faster by machinery, the looms were falling behind. As wonderful as the flying shuttle had been decades earlier it had, by the end of the Eighteenth Century become old technology and the need for power looms was pressing. Edward Cartwright, a clergyman, not a weaver this time, worked consistently on improving a design for one such piece of equipment. By the beginning of the Nineteenth Century Cartwright’s power loom was the norm in the weaving industry.

Cartwright’s power loom.

While Arkwright and Crompton had been unlucky in the patenting attempts of their inventions, Cartwright’s device was seen as being not only original but an indispensable piece of industrial equipment and Parliament awarded him £10,000 in 1809.

As Britain developed its cloth manufacturing industry, so long based on wool, new fibres made their way from foreign climes. Cotton was one of these. By the time of the Cartwright’s invention cotton was no stranger to the English mills.

Eli Whitney

Perhaps the most important invention for the processing of cotton was Eli Whitney’s cotton gin. This was an American design and was so successful in removing seeds and foreign matter from the cotton bolls that it remained largely unchanged from the original of 1792.

All this machinery made production very much quicker. While the early spinning jennys could be installed in a domestic situation their later cousins were far too big and required too much manpower for a normal sized house, let alone a cottage. The need for something stronger to drive them led to the use; firstly of horse power, but eventually water power was much better. Where running water was available, mostly where mills were already set, water power was not a difficulty. The answer lay in the steam engine.

James Watt

James Watt patented his steam engine in 1769 and its first application to the textile industry was in 1785 when it powered a cotton mill. By the end of the century steam was far more prevalent for powering textile mills than water was.

The result of all this activity was that the new innovations required large amounts of capital, as well as adequate space, to run. Such machines were not even dreamed of by the cottagers who had formed the basis of the old domestic system.

Machines would spell the end of the long established domestic system. What took its place was the factory.

The Factory System

Men with money invested it in textile mills. The mills needed money to set up with machinery and then they needed a labour force to make them earn their keep. Even though machinery had revolutionised the industry, making cloth faster than humanly possible by hand, it still required many people to run them efficiently. Machinery plus men under the one roof equalled the first factories.

It was making cotton textiles that first became mechanised and organised into a factory. It was not long before the woollen cloth industry followed suit and eventually other industries all started using the new ‘factory system’ as opposed to the long standing ‘domestic system’ of production.

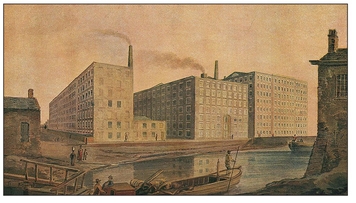

From 1760 until approximately 1800 the introduction of machinery and steam power altered the whole manufacturing process and, in this short time, it managed to produce a whole range of social problems too. Workers who had long been able to make extra money working from their own homes at their own times were now expected to go to the work site at specific times to work set hours. This automatically disqualified workers who lived any great distance from an industrial centre.

Cotton mill.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution means exactly that. Industry was revolutionised in a way that hadn’t been done for centuries, probably with the adoption of the domestic system in late medieval times. It has set a paradigm for industry ever since with a need to utilise new and more efficient machinery and technology, to gather its workers under a centralised building and to have a large well of capital to draw upon.

The effect on the domestic manufacturer was devastating. They could not compete with machine-made yarn or cloth in either speed or quality. Many people who had subsisted on a bit of domestic manufacture and a bit of agriculture could not exist on either. Many people sold up their small farms and went to seek work in the towns and cities. Others stayed on the land as farm labourers after selling their small holdings to bigger farms. The era of the small farm was over, just as the small manufacturer was too.

The population underwent a dramatic shift. Rural areas were often abandoned and some villages disappeared altogether as people sought work or opportunities abroad. Still, in 1801, according to records from the time, only one fifth of England’s population lived in urban areas and four-fifths stayed in the countryside. However, the Industrial Revolution had stimulated a major change and 50 years later the population had rearranged itself so that the percentage of town to rural dwellers was approximately half and half. By 1901 the numbers of 1801 had totally reversed and the towns held the bulk of the people and the rural areas had dwindled to a fifth of the overall population. For example:

- Manchester in 1800 had a population of 85,000; in 1850 it had expanded to 400,000

- Leeds in 1800 had a population of 53,000; in 1850 it had grown to 172,000

- Bradford in 1800 had 13,000 people; by 1850 it had become 104,000

Pollution

One of the negative outcomes for the increase of mechanised manufacture in the towns was air pollution. Charles Dickens paints a dark and dirty picture in Hard Times. Dickens, apparently, visited a Lancashire manufacturing town, Preston, at the time of industrial action by the workers.

It was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; but as matters stood it was a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage. It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and a trembling all say long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness.1

As Dingle Foot says in his introduction to this volume, Dickens was bored by the town, out of his usual setting and did not give himself the chance to get to know the people. He describes Coketown in unflattering terms and equates its population with the town’s physical attributes too.

Elizabeth Gaskell supports the idea that these textile factory towns were polluted. In North and South, her heroine, Margaret gets her first view of a northern industrial town, Milton, based on the author’s own experience of Manchester, from the train which is carrying her to it and she notices the difference between it and the south of England. The country carts ‘had more iron, and less wood and leather’ and there was less colour. Everything, Margaret thinks, has a sense of busy purpose about it.

For several miles before they reached Milton, they saw a deep lead-coloured cloud hanging over the horizon in the direction in which it lay…Nearer to the town, the air had a faint taste and smell of smoke; perhaps, after all, more a loss of the fragrance of grass and herbage than any positive taste or smell. Quick they were whirled over long, straight hopeless streets of regularly-built houses, all small and of brick. Here and there a great oblong many- windowed factory stood up, like a hen among her chickens, puffing out black, ‘unparliamentary’ smoke, and accounting for the cloud which Margaret had taken to foretell rain.2

By ‘unparliamentary’ smoke Gaskell refers to the ‘Act of Good government of Manchester’ of 1844. The act commanded that every factory furnace had a chimney that would ‘consume the smoke arising from such a furnace’. Obviously the act was not efficient in diminishing air pollution.

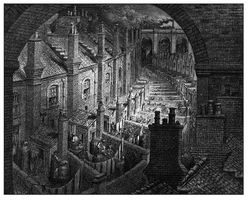

A city under a cloud.

Land Enclosure

With the disappearance of the small farms due to the decline of manufacture, the domestic system, the advances made in agriculture, plus large amounts of capital being pumped into the bigger farms, enclosure of common land was to be expected.

One of the profoundest effects on England through these changes was probably the social structure of the rural populations. Previously the boundaries had been somewhat blurred between the rural classes. With the emergence of the new factory system, the abandonment of small farming and the desperate need for work by the poorer people displaced from farm work and cloth making, the only option besides moving to the city, was to become labourers to the bigger and more impersonal farms.

At the top of the pecking order were the landlords who rapidly acquired more land. Secondly were the tenant farmers who leased the farms belonging to the landlords for large sums of money. They were professional farmers and could make the farms run at a profit big enough to pay their rent and themselves a decent wage. The labourers were at the bottom of the pile. They were paid pitiful wages for farm work, lived in rundown cottages, and had no land of their own. It is odd then that England was no longer self-sufficient in food production.

During the Eighteenth Century there was a big increase in population, from five million in the early 1700s to six and a half million in the middle of the century and approximately nine million by 1800. Within another 50 years the population of England had doubled to eighteen million. With a big part of the people involved in manufacturing non food stuff there was not enough emphasis put on domestic food production.

Urbanisation was responsible for a decrease in domestic food production but it also directed a change in the general eating habits of the English people. Before the Industrial Revolution people ate brown bread and unprocessed foods; but when people became urbanised they turned to white bread and began the tradition of tea drinking. There was a major decline in the home baking of bread. Bakery businesses grew as a consequence.

Overall living standards fell dramatically and between 1800 and 1834 they were the lowest they had ever been. Previously, farm labourers had usually lived within the confines of the farm with food plentifully provided by the farmer. As the Revolution steamrolled across England, this tradition was also lost. Farmers could sell excess food and for a good profit because of the demands of town dwellers. Farm workers moved out of the farm itself and had to find rented accommodation.

Women and children in the work force

But how were these two little girls to find time to do all this work for me? The whole day they were engaged, from six o’clock in the morning till bed time… the poor little girls had to work so hard for more than thirteen hours every day that neither of them could awake in time.3

Women and children made up much of the work force in the young factory system. They were employed more than they had ever been in previous labour systems and were employed in the factories to a greater extent than men. For instance, a flax spinning mill near Leeds, in 1832 employed 1,200 workers of which about two thirds were under the age of eighteen. This was a fairly typical ratio of the early factories.

The attraction of having such a young work force was that they could be paid a lower wage and they were more easily brought into line through physical restraint and intimidation. Men were slower to take on factory work preferring to stay with the tried and true method of working by hand.

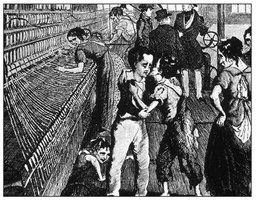

Children working in a textile mill in the Nineteenth Century.

The textile mills of the early factory system were not congenial places to work. They were noisy, hot and nasty and often dangerous. The hours were piteously long and the work repetitive to the point of insanity. There was no distinction made in the hours and conditions or types of jobs given to adults and children; all were required to work up to fourteen hours a day.

Pay could be irregular depending on the amount of production done at the time. It tended to be somewhat erratic and intense production could be followed by a lengthy and unpaid for lull. Not being able to pop out of the house and tend the garden or milk the cow, now that workers were congregating in the towns, meant that there was nothing to fill the gaps of inactivity and no wage. It also meant that the farm labourer and the factory worker alike were segregated even further from the rest of society and their potential for changing this was further diminished. Slums rapidly arose, not helped by the fact that the towns were just not equipped to manage the influx of population. The cramped conditions were highly unsanitary, depressing and degrading.

Children were the worst affected by the conditions often succumbing to infectious fevers that could not be fought because the small body was so weak and malnourished. Below is a report made on the appalling conditions that children were subjected to.

Report on the Condition of Children in Lancashire Cotton Factories [Report of Committee on Sate of Children in Manufactories, 1816 (III), pp. 139 – 140, 1796]4

It has already been stated that the objects of the present institution are to prevent the generation of diseases; to obviate the spreading of them by contagion; and to shorten the duration of those which exist, by affording the necessary aids and comforts to the sick. In the prosecution of this interesting undertaking, the Board have had their attention particularly directed to the large cotton factories established in the town and neighbourhood of Manchester; and they feel it a duty incumbent on them to lay before the public the result of their inquiries:

- It appears that the children and others who work in the large factories, are peculiarly disposed to be affected by the contagion of fever, and that when such infection is received, it is rapidly propagated, not only amongst those who are crowded together in the same apartments, but in the families and the neighbourhoods to which they belong.

- The large factories are generally injurious to the constitution of those employed in them, even where no particular diseases prevail, from the close confinement which is enjoined, from the debilitating effects of hot or impure air, and from the want of active exercises which nature points out as essential in childhood and youth, to invigorate the system, and to fit our species for the employments and for the duties of manhood.

- The untimely labour of the night, and the protracted labour of the day, with respect to children, not only tends to diminish future expectations as to the general sum of life and industry, by impairing the strength and destroying the vital stamina of the rising generation, but it too often gives encouragement to idleness, extravagance and profligacy in the parents who, contrary to the order of nature, subsist by the oppression of their offspring.

- It appears that the children employed in factories are generally debarred from all opportunities of education, and from moral or religious instruction.

- From the excellent regulations which subsist in several cotton factories, it appears that many of these evils may, in a considerable degree, be obviated; we are therefore warranted by experience, and are assured we shall have the support of the liberal proprietors of these factories, in proposing an application for the Parliamentary aid (if other methods appear not likely to effect the purpose), to establish a general system of laws for the wise, humane, and equal government of all such workers.

Finally action was taken to rectify this shocking state of child abuse. Sir Robert Peel, in 1802, put the facts before Parliament. Let it be noted that Peel himself was an employer of a thousand or so children. Outrage at the wretched conditions enforced on children led to a bill being passed for the health and moral welfare of the children in cotton factories. Children under nine were no longer allowed to be employed and the hours of labour were set at a maximum of twelve and none could be undertaken at night.

The factory buildings also had to be updated to comply with the new health regulations. Such requirements were: walls had to be whitewashed, ventilation had to be installed, and apprentices were to receive a new outfit once a year or more and were to attend church weekly so their souls could become as healthy as their bodies.

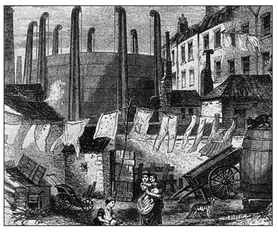

Children living in slums.

The Factory Act (1802)5

An act for the preservation of the health and morals of apprentices and others employed in cotton and other mills… Be it enacted that…all such mills and factories within Great Britain and Ireland, wherein three or more apprentices or twenty of more other persons shall at any time be employed, shall be subject to the several rules and regulations contained in this act…

…That all and every the rooms and apartments in or belonging to any such mill or factory shall, twice at least in every year, be well and sufficiently washed with quick lime and water over every part of the walls and ceiling thereof; and that due care and attention be paid by the master and mistress of such mills or factories to provide sufficient number of windows and openings in such rooms or apartments, to insure a proper supply of fresh air…

That every such master or mistress shall constantly supply every apprentice… with two whole suits of clothing…, one new complete suit being delivered to such apprentice once at least every year…

That no apprentice…bound to any such master or mistress shall be employed or compelled to work for more than twelve hours in any one day…. exclusive of the time that may be occupied by such apprentice in eating the necessary meals. Provided always that, from and after the first day of June, 1803, no apprentice shall be employed or compelled to work upon any occasion whatever between the hours of nine of the clock at night and six of the clock in the morning…

They must also receive some tuition in their trade and attend a church service on Sunday. Two independent inspectors were to have been appointed to visit the mills at regular intervals to ensure that the reforms were being carried out.

Real Reform?

The first ‘factory act’ paved the way for more reforms of working conditions, not limiting them to children nor to just the cotton industry. However, when evidence is examined from later sources it is rather difficult to see if the reforms really did much for the welfare of some of the workers or that many factories implemented them.

Evidence of Factory Workers of the Condition of Children [Report of Committee on Factory Children’s Labour, 1831 – 2 (XV) p.192, etc.] 1832 Evidence of Samuel Coulson

5047. At what time in the morning, in the brisk time, did those girls go to the mills?

In the brisk time, for about six weeks, they have gone at 3 o’clock in the morning and ended at 10, or nearly half past at night

5049. What intervals were allowed for rest or refreshment during those nineteen hours of labour?

Breakfast a quarter of an hour, and dinner half an hour, and drinking a quarter of an hour.

5051. Was any of that time taken up in cleaning the machinery?

They generally had to do what they call dry down; sometimes this took the whole of the time at breakfast or drinking, and they were to get their dinner or breakfast as they could; if not it was brought home.

5054. Had you not great difficulty in awakening your children to this excessive labour?

Yes, in the early time we had them to take up asleep and shake them, when we got them on the floor to dress them, before we could get them off to their work; but not so in the common hours.

5056. Supposing they had been a little too late, what would have been the consequence during the long hours?

They were quartered in the longest hours, the same as in the shortest time.

5057. What do you mean by quartering?

A quarter was taken off.

5058. If they had been how much too late?

Five minutes…

5061. So that they had not above four hours’ sleep at this time?

No, they had not…

5065. Were the children excessively fatigued by this labour?

Many times; we have cried often when we have given them the little victualling we had to give them; we had to shake them, and they have fallen asleep with the victuals in their mouths many a time…

And so it goes on listing accidents as a consequence of fatigue and the docking of pay while the child was off work due to the loss of a finger, regular beatings of children and instances of children, healthy before they began working in a textile mill but almost crippled after three years of labouring in one. This was a report made thirty years after Peel’s reforms.

Such damning reports lead to another factory act being made in 1833 with particular detail being directed towards child labourers.

Factory Act (1833)6

An act to regulate the labour of children and young persons in the mills and factories of the united kingdom…Be it…enacted…that…no person under eighteen years of age shall be allowed to work in the night-that is to say, between the hours half-past eight o’clock in the evening and half-past five o’clock in the morning…in or about any cotton, woollen, worsted, hemp, flax, tow, linen, or silk mill or factory, wherein steam or water or any other mechanical power is or shall be used to propel or work machinery…

And be it further enacted that no person under the age of eighteen years shall be employed in any such mill or factory…more than twelve hours in any one day, nor more than sixty-nine hours in any one week…And be it further enacted that there shall be allowed in the course of every day not less than one and a half hours for meals to every such person…

And be it enacted that… it shall not be lawful for any person whatsoever to employ in any factory or mill aforesaid, except in mills for the manufacture of silk, any child who shall not have completed his or her ninth year of age…

The 1833 factory act also mentions that the previous act of 1802 had specified that two inspectors be allocated to make sure that the reforms were being carried out. It appears that the inspections were not made as stipulated so the 1833 act made it law that the King should appoint four people with authority to inspect the mills and factories to ensure the amendments to the factory act, in regard to the welfare of children were implemented.

Fluff

Another problem facing textile workers, particularly cotton mill workers, was cotton residue being inhaled and causing respiratory problems. We have an excellent illustration of this, again from Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South. A young girl, Bessy, lying tossing and turning on her sick bed, tells Margaret about her illness.

Working in a cotton mill.

‘I think I was well when mother died, but I never been rightly strong sin’ somewhere about that time. I began to work in the carding-room soon after, and the fluff got into my lungs and poisoned me.’

‘Fluff?’ asked Margaret enquiringly.

‘Fluff,’ repeated Bessy. ‘Little bits, as fly off fro’ the cotton when they’re carding it, and fill the air till it looks all fine white dust. They say it winds round the lungs, and tightens them up. Anyhow, there’s many a one as works in a carding-room, that falls into waste, coughing and spitting blood, because they’re just poisoned by fluff.7

When Gaskell wrote her book the disease known as byssinosis had not been identified. Its common name was card-room asthma.

Industrial Revolution in London

While technology saw the rise of the factory system in many textile centres of England, London did not respond to the Industrial Revolution in the same way. There were no enormous textile mills or other steam powered manufacturing plants in London; it was very expensive to buy suitable land for factories in the city. This did not mean that the city did not play an important role in the textile industry.

What had been known as the domestic system before the Industrial Revolution became ‘sweated’ labour in London after 1800. The increased demand for cheaper goods, the influx of cheaper materials and a steadily growing population meant that for London to compete in the textile and clothing markets it had to take drastic action. Work standards broke down and semi-skilled labour replaced the skilled workers produced through rigorous apprenticeship. Lower wages were paid accordingly to the lesser level of skill and this kind of work attracted women who could often do the work at home. Others worked in what became known as ‘sweatshops’, mostly in salubrious attics or cellars supervised by a ‘sweater’ or ‘garret-master’.

The growth of these organisations meant that trained tailors, called ‘honourable’ for their work ethics and attention to high quality production, were overtaken by the ‘dishonourable’ sweat shops that exploited their workers. The employees of the sweat shops worked long, long hours, received meagre wages and were often required to pay much of this back to the employer in return for food and rent.

The Sewing Machine

The invention and implementation of machinary to do the basic production work of spinning and weaving meant that fabric could be produced much faster than previously and therefore the cost of it could come down within the reach of the general public. It had negative impacts on some parts of the textile industry but ultimatley it took over tedious hand work.

An early model domestic sewing machine.

There was an invention, made by an American in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that was to revolutionise domestic sewing as much as it did factory clothing production. Elias Howe was a mechanic working in a shop that repaired fine machinery. He became intrigued with the idea of a mechanical sewing process.

It took him several attempts to come up with a machine that would sew quickly and use a stitch, lockstitch, that wouldn’t just come out. Previously machines had been made and even patented but they relied upon chainstitch which was notrious for the stitches to pull out. Thomas Saint had brought one out 50 years before in England and in France Thimmonier employed 80 of them to make soldiers’ uniforms. Unfortunately his workshop was broken into by angry tailors who smashed the machines fearing they would put them out of work.

Elias Howe was not the first to invent the lockstitch although there is considerable doubt as to whether he ever knew of a previous lockstitch machine by a man called Walter Hunt who had devised a machine but never took the inventoin to patent.

Howe attempted several versions of a sewing machine. He tried manufacturing and selling the first, which had multiple problems attached to it, not the least being the sale price for it.

The second machine saw many of the glitches of the first sorted out but it still did not take on, partly because of the workers’ opposition to it. He did patent the second machine in 1846.

The sewing machine finally found interest in England with a corset maker who paid for the rights to produce it and pay royalties on machiens sold. Howe went to England at the invitation of the investor in order to design a sewing machine specifically for making corsets. It looked as though the sewing machine was set to take off.

Elias brought his family over from America, thinking they would all settle in Britain. Prosperity did not eventuate and Howe sent the family home again when he destroyed his relationship with the English corset maker. He followed not long after when he had gathered enough money for the ship.

On returning to America, Howe’s wife died. Hoping to make a living though his sewing machine, Elias tried to restart his business. However, during his time away his machine had been reproduced by other people, including Isaac Singer, founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

Howe and Singer became embroiled in a court case over the patent rights to the machine. After five years, Howe won out and Singer and his company had to pay Howe for royalties gained through Singer’s machine sales.

Ten years later Howe set up the Howe Machine Company of Bridgeport, Conneticut. The new venture proved profitable and when he died, only two years later in 1867, he was well and truly wealthy. The company continued until the mid 1880s, run by the inventor’s borthers-in-law.

A modern domestic Janome sewing machine.

Isaac Singer

Actor, inventor and industrialist, Isaac Singer is best known as the name behind the sewing machine. In 1851 Singer and Edward Clark, a lawyer from New York, set up a manufactury of sewing machines called I.M. Singer & Co. In 1865, well after the court battle with Elias Howe, the company was renamed the Singer Manufacturing Company.

Despite having to pay Howe a fortune in royalties for sales of a machine based largely on Howe’s design for lockstitch, Singer and his company did nothing but prosper. Isaac Singer died in 1875, nine years after his rival. The company continued without him, just as Howe’s did and in 1885 it brought out an improved machine with a vibrating shuttle.

During World War II a halt was put to the production of sewing machines so that full attention could be given to the making of armaments, specialising in artillery and bomb sights, though five hundred pistols had been made. Sewing machines returned to schedule after the war.

- In 1786 spun yarn of a particular quality was worth 38 shillings. In 1796 the same amount was only worth 19 shillings. The price continued to decline with it being worth 7 shillings 2 pence in 1806 and only 3 shillings in 1832. This devaluation meant that is certainly was no longer viable to produce hand spun thread

- Handcrafting stayed much longer as a viable production method of textiles in London than many of the other textile towns. One of its stable industries was tailoring

- In the late 1700s a man called Lieven Bauwens smuggled cotton spinning machinery out of England. He took it to Gent in Belgium and managed to kick start the mechanisation of the textile industry in his own country

- The American author, Alvin Toffler, born in1928, wrote, ‘To think that the new economy is over is like somebody in London in 1830 saying the entire industrial revolution is over because some textile manufacturers in Manchester went broke.’ Which shows how famous Manchester was for its textile industry

- During the Industrial Revolution Nottingham, was a major centre of lace production, particularly machine knitted lace

Notes

Dickens, Charles, Hard Times, Distributed by Heron Books, p. 24.

Gaskell, Elizabeth, North and South, Penguin books, Middlesex, 1978 (first published in Household Words 1854 – 5)

From Memoirs of a London Doll, Richard Henry Horne, 1846.

From English Economic History, pp. 495 – 6.

Sources of English Constitutional History, pp. 675 – 6.

Sources of English constitutional History pp. 726 – 7.

North and South p. 146.