THE RISE AND FALL OF BOURGEOIS Iranian society does not feature in anyone’s narrative of world history. The closest approximation is in Richard N. Frye’s book The Golden Age of Persia, subtitled The Arabs in the East.1 But even there the seeming contradiction between the title and the subtitle epitomizes the problem of representing Iranian history in the early Islamic centuries. Should the extraordinary flourishing of Iran’s highland plateau be ascribed to the Arabs who invaded or to the native Iranians? To Muslims exclusively or to the society as a whole? Is the cultural dynamism to be read only in Arabic texts or in Persian writings as well? Only in books by Muslims or also in the writings of Zoroastrians, Christians, and Jews?

The practice of historians has long been to subordinate the story of Iran in this time period to the story of Islam. The militant movement that overthrew the unimpeachably Arab caliphal dynasty of the Umayyads in 750/108 came from Iranian territory and engaged many Iranian converts to Islam in both its leadership and its soldiery. Yet it is represented primarily as a turning point in the history of Islam. The Abbasid dynasty that was the beneficiary of this movement gradually adopted many of the ceremonial, administrative, and cultural practices of the Iranian Sasanid regime that had succumbed to the Arab invaders a century earlier. Yet this is most often seen as symptomatic of Islam’s capacity for absorbing and breathing new life into the traditions of its diverse peoples. The personalities, forces, and controversies that shaped the developing institutions of the Islamic religion did not just play out on the Baghdad stage, but also in burgeoning cities throughout Iran. Yet insofar as the language in which these controversies are recorded was almost exclusively Arabic, their historical moment is elided with that of the Arab Muslims whose extraordinary conquests had brought Iran into the caliphal empire.

All these representations are valid when seen through the prism of Islamic history, of course, although they are somewhat less valid as part of Arab history, because specialists on matters Arabian frequently forget to mention how many of the most prominent authors of medieval works in Arabic grew up in Persian-speaking homes. In either case, however, what is missing is any narrative of the transformation that the Iranian heartland as such underwent between 650/29 and 1000/390, or of the subsequent undoing of much of that transformation between 1000/390 and 1200/696.

A politically oriented historian might cite the lack of a centralized Iranian state, and Iran’s actual incorporation in an empire centered on Iraq, as adequate explanation for this skewed perspective. After all, when the temporal power of the caliphate began to erode in the ninth/third century, several parts of Iran became wholly or partially independent under ruling houses of Iranian ethnic origin. The importance of these successor states, and of such specifically Iranian characteristics as their use of pre-Islamic symbolism and patronage of Persian-language writings, has been amply and properly recognized.2 But because no successor state succeeded in establishing itself over most of Iran until the Oghuz Turkomans created the Seljuq sultanate in the eleventh/fifth century, the separate histories of these ethnically Iranian principalities, which were frequently at war with one another, cannot easily be summed to a history of Iran as a whole.

Although this book has concentrated on economic aspects of Iran’s transformations because they are the ones that are the hardest to extract from sparse and often indirect sources, it is reasonable to close with some consideration of Iran’s early Islamic history in a much broader compass, namely, its impact on world history.

Comprehensive histories of Iran through the ages lavish attention on a series of pre-Islamic empires: Achaemenids, Seleucids, Parthians, Sasanids.3 But in every one of these instances, the capital province of the empire was Mesopotamia, usually around the Baghdad area, and the surviving political narratives provide the greatest detail in their accounts of conflicts with foes coming from west of Mesopotamia: Greeks, Phoenicians, Romans, Byzantines. Information about the Iranian plateau is rare; without archaeology almost nothing would be known. The few facts that are available, however, are consistent with the image of a rural aristocracy living quite grandly, a village-based grain-growing economy with very little urbanization, and a role in the imperial polity of supplying cavalry for the armies of the kings. Oddly enough, this description is not far from the image of Iran in the post-Seljuq period down to around 1500/905, except for a dramatic increase in pastoral nomadism; a persistence of city life, though on a reduced scale from its heyday in the tenth/fourth century; and the disappearance of Mesopotamia as an imperial center to which the society of the plateau is subordinate. As the general histories make clear, the horse warriors of the Seljuq and post-Seljuq era generally fight for rulers who are based in Iran proper.

What was the impact, then, of the centuries intervening between the fall of the Sasanids and the rise of the Seljuqs, when Iran became suddenly transformed into one of the world’s most productive and dynamic urban societies? Before addressing this question, let us take a more general look at the transformation.

In moviemaking, a jumpcut is an abrupt, even jarring, change of scene that sometimes makes the screenplay hard to follow. The preceding chapters have included many such abrupt jumps from one topic to another. So now I wish to draw the assorted topics together in a more narrative vision of Iran’s economy in the early Islamic centuries, connecting the arguments that have been advanced here with some others that I have elaborated in earlier publications.

When the Arab invasions brought the Sasanid Empire to an end, the invaders had no particular plan for what would come next. Different conquered areas adapted to the change of regime in different ways. In the Iranian plateau region, the economy that the Arabs gained control of was primarily agricultural and self-sufficient, though there was also a substantial trade, much of it in luxury goods, along the route linking Mesopotamia with Central Asia and China. This trade was anchored by a number of small, walled garrison towns. The fact that Arab armies campaigned as far east as Kyrgyzstan, more than 2000 miles from their desert homeland, while elsewhere stabilizing their borders much closer to familiar territory, to wit, along the Taurus Mountain frontier of southern Anatolia and at the first cataract of the Nile in Egypt, indicates that the new rulers fully understood the importance of the Silk Road trade. In all likelihood, some Arab merchants or stockbreeders even participated in the trade before the Muslims came, or they themselves became Muslims.

The conquests not only brought to power a new ruling elite, but also delivered large quantities of money into Arab hands in the form of booty, military pay, and tax revenues. Unlike Iraq, Egypt, and Tunisia, where the Arab presence was concentrated in large encampments, or Palestine and Syria, which were contiguous with traditional tribal grazing lands in the Arabian desert, Muslim rule in Iran operated through smaller army garrisons spotted at a number of strategic locales. Gorgan received more Arabs than most other places because it guarded the Karakum Desert frontier that separated Iran from the lands of the Turks to the north, and Marv received the most because it protected the Oxus as well as the Karakum frontier. Farther to the east, a large Arab garrison at Balkh anchored Muslim control in northern Afghanistan and the mountainous lands north of the Oxus. All of this before the year 750/132.

In Qom, one of the smaller Arab settlements, the question of how to adapt to life in Iran found an answer that seems to have reflected conditions in the piedmont districts more generally. Looking for a place to invest their money (my apologies for the anachronistic modern terminology), certain Arab entrepreneurs, almost certainly Yemenis by origin, hit on the idea of digging qanats and creating new villages devoted to the cultivation of cotton.

Islamic law as it crystallized in the early Abbasid period, when these villages were forming, included a “homestead” provision that granted freehold ownership to people who brought uncultivable land into production. Founding new villages in areas of desert watered by newly dug qanats thus provided an avenue for intrusive Arabs to become landowners without contesting land rights with the much more numerous Iranian landowners. The latter continued in possession of their own villages. Piedmont Iran’s geography and long-established techniques of qanat excavation opened up this possibility in a way that could not easily be imitated in other conquest areas. Farther west in the Zagros Mountains, or farther east in stretches of arable land along the Tejen, Murghab, Oxus, and Zeravshan rivers, Arab settlers seem to have found other sorts of opportunity. But the information particular to Qom is particularly revealing.

To repay the high cost of qanat and village construction, the new entrepreneurs, which included a minority of non-Muslims, planted summer crops instead of grain. Wheat and barley, the mainstay of Sasanid agriculture, were normally grown on rain-fed, spring-fed, or runoff-irrigated land that did not require so great an investment in irrigation. Pomegranates, apricots, melons, and vegetables for local consumption were appropriate for irrigated gardens close to towns, but the ideal crop for somewhat more distant villages was cotton, a plant that was unfamiliar to most Iranians but that Yemeni Arabs knew how to cultivate and process from their land of origin.

In terms of total acreage, cotton did not come close to displacing grain, but its impact transformed the nonfarming economy nevertheless. Cotton had to be freed of seeds, cleaned, combed, spun into thread, and woven into cloth. Dying, bleaching, fulling, and tailoring were also involved, depending on the fabric being produced. These industrial processes entailed a higher concentration of labor than farming villages could normally supply, and the transport and marketing of finished products similarly depended on well-developed distribution systems. Thus the emergence of cotton as an agricultural commodity provided an economic impetus for the governing points in which the Arabs had planted garrisons to expand into towns and cities.

In Sasanid times cotton farming and cotton cloth had been virtually unknown in the plateau region, although it had already been introduced into Central Asia on a fairly minor scale through contacts with India. But by the early ninth/third century cotton was already developing into the economic mainstay of an Arab-Muslim society that no longer occupied itself primarily with military operations. At the same time, cotton acquired a strong doctrinal association with Islam. Learned Muslims in Iran, a large proportion of whom, apparently around 40 percent, were engaged in or funded from one or another aspect of cotton production, popularized antisilk, pro-cotton teachings. Some of these prescriptive hadith they traced directly to Muhammad and others to early Arab responses to encounters with the defeated Sasanid elite. Religious precepts thus encouraged a rapid growth in cotton consumption as new converts to Islam sought to emulate the flowing, plain-cloth style of dress of the Arabs and the earliest converts. Sasanid-era silk brocades remained popular among the elite strata of the majority non-Muslim population. Silk also came into fashion among the Muslim civil elite, particularly in Baghdad; but the religious prohibitions were honored nevertheless through the government’s establishment of tiraz factories. The cotton (and in Egypt, linen) fabrics produced in these factories for fabrication into robes of honor made explicit the connection between Islam and textile preferences.

A visible competition arose between a Muslim lifestyle and a non-Muslim lifestyle, particularly in the growing cities. This was manifested not just in clothing preferences, but also in ceramics. Muslim austerity and reverence for the Arabic script contrasted dramatically with Sasanid luxury and figurative ornamentation. Cotton probably also contributed to the spread of Islam through the farmers attracted to work in the new cotton villages being classified as Muslims, regardless of their private convictions or depth of knowledge of the Muslim faith.

The differential between tax rates on grain and on cotton shows that growing cotton was highly profitable. The fact that Iraq was geographically unsuited to growing cotton enhanced this profitability because Arabs and new converts there consumed cloth imported from Iran. The cotton boom fueled exuberant growth in the size of Iran’s cities during the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries. It provided money for urban construction and land speculation; it provided employment in textile manufacturing; and it encouraged new converts to migrate to the cities and share in the Islam-focused prosperity. Never before had a domestically produced industrial commodity played such an important role in the overall Iranian economy, or competed in importance with the products carried by Silk Road caravans.

The scholarly elite (ulama) of the Muslim community, through their religious endorsement of cotton consumption and deep involvement in its production, stood at the center of urbanization and commerce. Through their own enterprise or through intermarriage, the most illustrious scholarly lineages had acquired, by the late tenth/fourth century, such significant commercial and landowning interests that they constituted a patrician class that dominated local urban society and politics, more on the pattern of the urban elites of late medieval Europe than of the earlier, legally defined Roman patricians. To be sure, many ulama families had commercial interests other than, or in addition to, cotton; but the wearing of plain white cotton (or linen) became the hallmark of the religious profession, and continues to be so to the present day.

A biographical note about an eminent scholar from Gorgan epitomizes this development. After praising Abu Saʿd al-Ismaʿili (d. 1007/397) for his erudition in Arabic and Islamic law, his piety, and his generosity, the biographer writes:

Among those things by which God blessed him was that when his death drew near, all of what he possessed by way of wealth and estates departed him. He had sent cotton to Bab al-Abwab [Derbent on the western side of the Caspian Sea]; it was all lost at sea. He had goods that were being transported from Isfahan; Kurds descended upon them and took them. He had some wheat being shipped to him from Khurasan; a group of people fell upon it and plundered it. He had an estate in the village known as Kuskara; Qabus ibn Washmagir [Gorgan’s ruler at that time] ordered that its trees be uprooted, and they were. The qanat was filled in and all his property seized.4

Iran’s creative urban culture continued to expand even as the cotton boom waned in the tenth/fourth century. Centuries-old traditions do not easily pass away, and the landowning families that joined the Muslim community in great numbers in the late ninth/third and early tenth/fourth centuries saw no reason to ape the Arabs just because Muhammad happened to have been born in Mecca. By this time the caliphate had lost political control, and local rulers of Iranian descent had taken power in most parts of Iran. With them, pre-Islamic styles and tastes reappeared, and the Persian language enjoyed a literary revival. In the cities, society became more complex. Some patrician families retained attitudes rooted in earlier, Arabcentered, Muslim practice; others favored newer attitudes and practices that were more responsive to the indigenous Iranian population, and more welcoming to new converts. This division contributed to a growing current of factional conflict even though the nominal basis of the conflict was differing (Sunni) views on Islamic law.

Cotton continued to be a mainstay of the manufacturing and export economy, but among the civil elite it had certainly lost its cachet as a preferred clothing textile by the mid-tenth/fourth century. At the same time, city growth through rural–urban migration, partly prompted by conversion and partly by economic opportunity, was reaching a point where the surplus food production of the labor-starved countryside was barely enough to sustain the populations of nonproductive urbanites. In some regions, such as the area around Nishapur in Khurasan, the percentage of the population living in the ten largest cities became comparable to the rate found in northern Italy and Flanders, the most highly urbanized parts of Europe. Unlike their European counterparts, however, Iran’s plateau cities did not have the benefit of inexpensive water transport for bringing foodstuffs from distant growing regions.5 Instances of drought and crop failure thus became increasingly perilous, leading governments to lower the tax rates on wheat and barley in an effort to sustain the necessary level of food production. A likely consequence would have been a partial shift from cotton to grain farming. This in turn would have touched the economic life of the cities by reducing the volume of cotton manufactures and exports.

Though a string of bad winters in the first half of the tenth/fourth century gave northern Iran a taste of what a major change in the weather might bring, the Big Chill did not set in until the eleventh/fifth century. By that time the bourgeois life-style fostered in large part by the cotton boom, and manifested in the social dominance of the patrician class, was already showing signs of stress. Factional feuding along religious lines had become endemic, and leading patrician families were sometimes bitterly at odds with one another. Episodes of famine and disease seem to have become more numerous, but the historical narratives are too spotty to be sure that this was the case.

The narratives more reliably inform us of an unprecedented movement of the Oghuz Turkomans from Central Asia into Iran. Though the stereotype of Central Asian nomadic society focuses on horse herding, the tribes that entered Khurasan at this time herded both horses and one-humped camels. Being essential for military purposes, the former probably outnumbered the latter. But the camels provided an important economic link with the caravan trade along the Silk Road. The Oghuz pastoralists interbred their one-humped females with two-humped males to produce unusually large and strong animals that were ideal for carrying loads or, in the case of females, for soldiers riding through desert terrain. The traditional lands of the Oghuz were located in the northern reaches of the Karakum Desert. The new lands they sought in their migrations were on the considerably warmer southern fringe of the same desert.

Exactly why the Turkomans were allowed to enter Khurasan is unclear, but Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna, who authorized their relocation, probably assumed that they would fit reasonably well into the economy as producers of valuable livestock. On the Oghuz side, the cooling of the climate must have enhanced their desire to relocate, if it was not the sole rationale, because their one-humped camels had a hard time surviving cold winters. As it turned out, these first Turkoman immigrants turned to pillaging, and some were driven away by the Ghaznavid army. Continuing livestock problems may well have contributed to this, because, instead of returning to Central Asia or moving back north to Khwarazm, many made their marauding way deeper into Iran. Ultimately, they found their way to Anatolia.

The next wave of Oghuz also petitioned to move from the northern Karakum to the warmer southern side of the desert, so it is likely that if the first wave had been experiencing livestock problems, the second wave was too. Fearing a repetition of the pillaging carried out by the earlier migrants, Sultan Mahmud’s son Masʿud forced the new group, led by the Seljuq family, into a military confrontation. Sultan Masʿud lost the crucial battle of Dandanqan and ceded Khurasan to the Seljuqs.

Unlike the Oghuz who had preceded them, or the Oghuz who ravaged Khurasan more than a century later after inflicting a surprise defeat on Sultan Sanjar, the last powerful Seljuq ruler, in 1153/547, the tribespeople that the Seljuqs led into Khurasan remained disciplined and helped the new rulers build a unified and comparatively peaceful domain extending from Iraq to northern Afghanistan. As for the economy, the noted historian Anne Lambton has written: “The Saljuq invasion does not appear to have caused a major break in the general continuity of rural prosperity.”6 However, the supporting evidence cited in her accompanying discussion mostly concerns southern Iran, which was less affected by the Big Chill. Khurasan, she admits, declined significantly in importance. Seljuq land policies featured increased. reliance on land grants (iqtaʿ) in return for military or government service. This may have temporarily raised revenues by giving the grantees license to oppress the peasantry, but it would have done nothing to restore flagging production in areas facing environmental deterioration. Nor is it likely to have encouraged landowners to invest more in their properties.

The superior leadership of the Seljuq family probably stemmed from prior involvement with caravan trading along the Silk Road. Like the Mongols of the thirteenth/seventh century, the Seljuqs focused their economic attention on long-distance trade. Among other effects, this served to popularize artistic styles and techniques derived from Chinese models and to encourage the growth of luxury consumption in ruling circles.

The undeniable prosperity of early Seljuq times could not conceal the fact that the agricultural infrastructure of northern Iran was suffering badly from nomadic incursions, rural insecurity, government neglect, and (especially) the Big Chill. Most cities suffered severe factional discord. The factional enmity dated from the tenth/fourth century, but its increasingly violent manifestations bespeak a competition for material resources that were becoming increasingly scarce and unreliable.

By the early twelfth/sixth century, northern Iran was in a declining condition. Members of patrician families that had the necessary financial means and scholarly connections outside Iran migrated to Iraq, Syria, Anatolia, or India. The patrician-dominated bourgeois market that had shaped consumption in pre-Seljuq times faded away, and Iran entered a long period of minimal contribution to the religious culture of Islam. The inability of the Khwarazmshahs to restore prosperity and order after Sanjar’s reign highlights the degree of damage Iran suffered during the Big Chill. By then warmth had returned, but Iran’s human and economic resources were too depleted to permit any significant recovery before the Mongol onslaught.

On a world scale, Iran’s moment of efflorescence had five significant impacts that have no parallel in earlier or later Iranian history. First, Mesopotamia under the Abbasid caliphs became the center of a vast and balanced economic region stretching from Central Asia to Tunisia instead of the eastern border of the lands around the Mediterranean. The wealth in silver dirhams derived from taxation and commerce in the lands to the east of the Zagros mountains exceeeded the wealth in gold dinars derived from the older urbanized economies of Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and North Africa. Where the various pre-Islamic dynasties that ruled from Mesopotamia between 500 BCE and the beginning of the Arab conquests had repeatedly sought to expand westward, the Muslim state paid much greater attention to eastern affairs. Abbasid caliphs rarely set foot in Egypt, Palestine, or coastal Syria; and Tunisia was the first province to be granted autonomy—in return for an annual tribute payment—by the Baghdad caliphs shortly after the year 800/183. By contrast, the first ten Abbasid rulers were all deeply involved in military campaigns or political machinations on the Iranian plateau, and several of them (e.g., al-Mahdi, Harun al-Rashid, al-Maʾmun, and al-Muʿtasim) spent substantial amounts of time there.

One reflection of this eastern orientation was a change in the locus of trading momentum. The Silk Road had always found its primary western terminus in one of a series of Mesopotamian capitals from Babylon to Ctesiphon that were built near the point where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers flow nearest to one another. Baghdad proved to be the last of these. But under earlier dynasties, substantial quantities of Silk Road goods had moved on up the Euphrates by caravan to find their way into Mediterranean commerce, usually being sold at entrepots like Dura Europus or Palmyra located near the frontier between the state based in Mesopotamia and some rival to the west. The early Islamic centuries, however, saw no great trading centers in those areas, nor does it appear that merchants in Syria, Egypt, or Byzantine Anatolia traded very extensively with Baghdad. It seems, rather, that the growing prosperity of urban Iran created an expanded outlet for Silk Road commodities that in earlier centuries had simply transited across northern Iran by caravan without being subject to much market activity at intermediate points. The upshot of this development is that the preferences and styles of the people living in the cities on the Iranian plateau region became defining components of the emergent Abbasid culture of Islam.

Second, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria were so overshadowed by Iran that they hold a comparatively negligible place in the history of the Middle East between 750/132 and 1100/493. This had never happened since the advent of the pharaohs, and it was not to happen after the undermining of the Iranian economy by the Big Chill allowed the coastlands of the Mediterranean to resume the paramount role in the Middle East that they continue to play to the present day. It is symptomatic of this diminished status that the only truly important Muslim political phenomenon at the eastern end of the Mediterranean after 750/132, the rise and fall of the Fatimid state in Tunisia, Egypt, and coastal Syria between 909/296 and 1171/566, defined itself in opposition to Abbasid Baghdad, both politically and doctrinally, but never acquired the power to mount a credible military challenge.

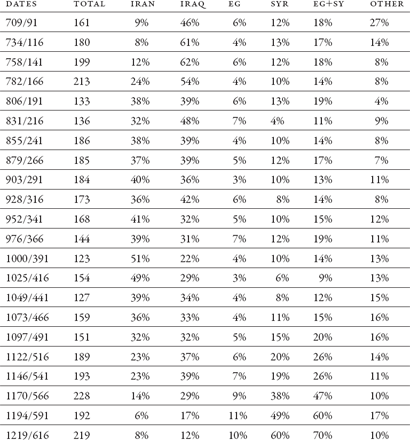

Another sort of evidence comes from a tally of geographically specific names in comprehensive biographical dictionaries of Islamic religious scholars. Between 743/125 and 1179/575, the proportion of notable scholars from Egypt and Syria/Palestine combined never exceeds 20 percent. Then it suddenly shoots up to a dominant position. By contrast, the proportion of scholars from Iran alone never falls below 30 percent between 840/225 and 1131/525. Then it tumbles (see Table 5.1).

How different medieval Mediterranean history might have been if Baghdad’s rulers, and their local successors in various parts of Iran, had cared about what happened in the west. Spain went its separate way. Tunisia’s conquest of Sicily did not interest people in the east. The Fatimid takeover of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco was a distant event of little note until the new Ismaʿili Shiʿite countercaliphate successfully expanded into Egypt and parts of Syria. And even then, the Ismaʿilis in Iran—the Assassins—loomed as a more potent threat in the imaginations of men of affairs in Mesopotamia and Iran.

Would greater attention to the affairs of Muslims living to the west of the Syrian–Iraqi desert have meant a stronger, more coordinated, and more aggressive attitude toward Christian Europe? Would it have enlivened Mediterranean trade? Would it have enhanced Europe’s awareness of and concerns about Islam? There is no way of telling. But it is strikingly apparent that the eleventh/fifth century, when climate change triggered widespread economic difficulty in Iran accompanied by nomadization, urban decline, and the emigration of the learned elite, also saw a marked revival of economic, cultural, and political interaction among the various Muslim and Christian principalities bordering on the Mediterranean. It is not inconceivable that the Mediterranean revival depended in some measure on the waning of Iran’s dynamism.

TABLE 5.1 Regional Representation among Muslim Religious Scholars

The third broad impact of Iran’s moment in the sun was that it forever changed the template of life on the plateau. Though nomads would from time to time ravage the land and bring down ruling dynasts, the idea of Iran as a land of cities persisted. Even when landowners enjoying royal favor came to control scores of villages, the pre-Islamic pattern of a warrior aristocracy settled in a dispersed fashion throughout the countryside never returned. The new landowners either were tribal chieftains, in which case they might indeed live in the country, but as pastoralists, or chose to live in or near town and send their agents to collect rents from their villages. To this day Iranians identify themselves by the urban center of the region they come from and by its traditional customs and local manufactures. They are Rashti or Shirazi or Tabrizi. Without the urbanization of the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries, this pattern would not have been there to guide the country’s recovery in the fifteenth/ninth century after a century of Mongol rule and the renewed disruptions of the Timurid era.

Language is the fourth area of impact. Every historian of Iran and of Islam has speculated on the reason or reasons for the failure of Arabic to achieve the dominance in Iran that it gained in the other regions conquered in the initial Islamic conquests. New Persian, a streamlined koine written in Arabic script, first appeared during the period of Iran’s economic boom; and great works of literature were already being authored in this language by the time the Big Chill set in in the eleventh/fifth century. This did not mean, however, that the several Middle Iranian languages of preconquest times—Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian, Bactrian, Khwarazmian, and so on—promptly disappeared. Indeed, Yaghnobi, a modern descendant of Sogdian, is still spoken in parts of Tajikistan. So not only was New Persian distinctive in its use of the Arabic script, but it saturated and lent linguistic uniformity to an Iranian language zone that had previously been multilingual and politically divided among a number of principalities.

Religion, as symbolized by the Arabic script, is the ostensible common denominator underlying this newfound linguistic uniformity. Zoroastrians continued to write religious books in Middle Persian. But to the degree that Islam had anything to say doctrinally about language, it favored Arabic, the language of the Qurʾan. Moreover, the religious elite of the Muslim community preferred for many generations to write in Arabic, leaving New Persian, at least initially, to the poets, storytellers, and historians. References to Islam or its teachings are uncommon in the corpus of early compositions in New Persian. However, that corpus is quite small and consists mostly of poems and romances before the tenth/fourth century.

An alternative common denominator could be the urban-based economic linkages that grew out of the cotton boom that began at the beginning of the ninth/third century. Muslims played the dominant role in building the new economy and populating the growing cities. They also became the most active participants in overland trade as they transported cotton cloth (and other goods) from as far east as Samarqand toward the great consumption center of Baghdad. New Persian, therefore, may have arisen the way Swahili and Bahasa Indonesia did in later periods of Islamic history, namely, as the language of merchants who resorted to a simplified grammar and morphology to gloss over the differences among the Middle Iranian tongues used in various localities, and who found an easy way to incorporate Arabic loan words by adopting the Arabic script. Known to all literate Muslims, but probably not to most non-Muslim Iranians, the Arabic script would similarly have afforded a means of overriding the preceding diversity of Middle Iranian writing systems.

Looking at the innovators of New Persian as a newly rising class of Muslim merchants and manufacturers responding to a pressing need to communicate with their counterparts in other parts of the Iranian cultural zone would help explain the uniformity, simplicity, and broad geographical extent of the new tongue. And it would raise the possibility that the Arabic script was deliberately intended to define a specifically Muslim commercial and cultural network. However, linking the emergence of New Persian to the cotton boom is entirely speculative. No commercial writings have survived from the period in any language, and the number of Iranian poets known to have written in Arabic dwarfs the handful who experimented with Persian.

By contrast, linking the decline of the Iranian agricultural economy in the era of the Big Chill to the spread outside Iran of New Persian is fairly obvious. No New Persian authors are known to have worked outside Iran before the Seljuq period, but by the thirteenth/seventh century both Anatolia and India were known for the exquisite Persian verses composed there by Jalal al-Din Rumi (d. 1273/671) and Amir Khusraw (d. 1325/725), respectively. What is important about these master poets for present purposes is not their personal lives but the fact that they rhapsodized for Persian-speaking audiences and had Persian-speaking colleagues and imitators in these foreign lands. So far as is known, the pre-Islamic Iranian dynasties never exported their languages to other lands. Not even to Mesopotamia, which was under Iranian rule for most of the millennium preceding the Arab conquests. What supported the spread of New Persian from the Seljuq era onward was not just the military success of the Turkoman warriors in Anatolia and Afghan tribesmen in northern India, but the migration out of Iran of literate scholars and litterateurs relocating themselves in response to deteriorating conditions in their homeland. To be sure, the Mongol invasion in the early thirteenth/seventh century put a capstone on Iran’s decline and forced many people to flee the destruction of their cities and not just the freezing of their crops. But there is ample evidence that the Iranian diaspora was well under way before the Mongols arrived. And there is similarly ample evidence that the emergence of New Persian as a cosmopolitan language of administration and culture from the Bay of Bengal to the Aegean Sea left a telling mark on world history.

The fifth and final impact of Iran’s boom and bust lies in the area of religion. In the sixteenth/tenth century, under the aegis of the Safavid dynasty, Iran became both declaratively and practically a Shiʿite land. Scholars disagree about how well implanted in the country Shiʿism was before the advent of the Safavids and on the extent of the coerced conversions that took place once the new identity was declared. All agree, however, that the interposition of a Shiʿite Iran between a Sunni Ottoman state to the west, a Sunni Uzbek state to the northeast, and a predominantly Sunni Muslim presence in India to the southeast powerfully shaped the history of the Muslim world from that time until the present.

From the ninth/third through the eleventh/fifth century, on the other hand, Iran was a predominantly Sunni land. To be sure, there are many indications that Shiʿites constituted a strong presence from time to time. The Buyid dynasty, for example, adhered first to the Zaidi and then to the Imami form of Shiʿism. And the Ismaʿili movement attracted many believers, particularly in the time of the Big Chill. Nevertheless, any tally of writers, thinkers, and religious leaders for the period of rapid urbanization and the cotton boom will come up with vastly more Sunnis than Shiʿites. Shiʿite ulama composed their own lists of leading scholars, but the city-based biographical dictionaries that have played such an important role in the arguments of this book are almost entirely Sunni and much more extensive than any Shiʿite compilation. Moreover, as table 5.1 shows, the Sunni intellectual output of Iran overshadowed almost every other region of the caliphate during the boom period. Although Ibn al-ʿImad, whose biographical compilation provided the data for the table (see the earlier discussion of table 4.1), was himself a Syrian, the combined share of Islamic scholarship apportionable to Egypt and Syria combined never exceeds 20 percent before the late Seljuq period

The elite emigration that took place from the late eleventh/fifth century onward effectively stripped the Sunni mass of the population of its religious leadership while at the same time the factional discord and shrinking subsistence base of the cities in the north destroyed many of the mosques and seminaries (madrasas) that had nurtured that leadership. The madrasa as a dedicated center for higher religious education had originated in Iran in the tenth/fourth century, if not before, and the institution had spread throughout the country before migrating into non-Iranian lands, more often than not with Iranian professors as inaugural academic directors. But by the beginning of the thirteenth/seventh century few noteworthy seminaries were still functioning, particularly in comparison with the many that were then flourishing in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and elsewhere.

It could be argued, of course, that the famously destructive onslaught of the Mongols would have wiped out Iran’s Sunni religious leadership even if it had not become depleted before Genghiz Khan’s first invasion in 1218/614. But this would make it difficult to account for the strong persistence of Sunni Islam in Central Asia, where the Mongol domination lasted even longer. It seems, rather, that the economically induced erosion of the Sunni spiritual leadership left Iran open to the much more populist and less legalistic guidance of Sufis, prominent members of the family of Ali, and Shiʿite preachers who ascribed divinely ordained leadership to that family. In other words, the rise of Iranian Shiʿism was facilitated, though not caused, by the collapse of what had once been a powerful, wealthy, and highly institutionalized Sunni religious establishment.

The study of world history over the past thirty years has looked with favor upon Fernand Braudel’s threefold division of time and causation: “Events” are the happenings of any given moment and should not normally command the close attention of scholars interested in the grand sweep of history. “Conjunctures” occur when various forces and institutions come together in an often complex fashion to shape a new historical tendency over a period of decades or more. And the “longue durée” involves trends that are so drawn out chronologically as to be largely unnoticed at the time even though they can have a profound impact that lasts for centuries. Narratives concentrating on the last two of these historical dimensions commonly strive to look beyond traditional political boundaries and dynastic eras.

The idea of a “moment” in world history elides these three dimensions. It concentrates on a particular place, the Iranian plateau, at a particular time, the ninth/third through twelfth/sixth centuries. Some of its arguments deal with humdrum events: the decisions made by agricultural entrepreneurs to invest in irrigation and grow cotton; or the decisions made by camel breeders to move their livestock to warmer pastures even in the face of military opposition. Other arguments are more conjunctural: the intersecting of religious teachings, economic benefit, and symbolic assertion of Muslim supremacy in the development of an urban-based cotton industry; or the coming together of agricultural decline, nomadization of the countryside, and urban factional discord to prompt a far-reaching diaspora of Iran’s religious and intellectual elite. Still others relate to the “longue durée,” notably the hypothesis that the northern Middle East experienced a Big Chill that lasted for more than a century.

From a world historical perspective, the impact of this moment was both complex and longlasting. But the story told here has been primarily the story of Iran in an era that is commonly given short shrift by historians. The economic and cultural efflorescence fostered by cotton production and rapid urbanization on the Iranian plateau in the first three Islamic centuries differed profoundly from anything that had happened in Iran before. And even though a change in climate brought an end to Iran’s agricultural prosperity and exuberant urban society, the traces of what the Iranians had created spread far and wide, and the land itself was left with a memory and a template of urban life that served as a base for revival in later and more propitious times. It was a moment to remember.