About the influence which the physical theory of relativity had upon purely mathematical research different mathematicians will be of different opinions. But it is unlikely that anybody today would agree with E. Study, Felix Klein’s contemporary and life-long enemy, a man of considerable merit in his field and of violent temper, who, in a book published 1923, accused the writers on relativity theory and tensor calculus of having laid waste a rich cultural domain (ein reiches Kulturgebiet der Verwahrlosung anheimgegeben zu haben), that rich cultural field being the algebraic theory of invariants. What got Study’s goat was the fact that the symbolic method and the classical notations of that theory had been more or less ignored by the relativists. I shall come back to his problems later on. Anyhow I would not stand here and try to say some words about the topic which the program announces, were I not convinced that relativity theory during the last decades has been an invigorating rather than a devastating influence in the development of several branches of mathematics, including the theory of invariants. Nor is it difficult to prove my point; the facts speak a too unmistakable language.

The relativity problem is one of central significance throughout geometry and algebra and has been recognized as such by the mathematicians at an early time. It played a great role in Leibniz’s philosophical-mathematical ideas. In the nineteenth century the concept of a group of transformations was devised and developed as the adequate tool for dealing with it. Suppose a realm of objects, which may be called points, is given to you. Those transformations, those one-to-one mappings of the point field into itself which leave all relations of objective significance between points undisturbed, form a group, the group of automorphisms. If in some way coordinates, self-created reproducible symbols like numbers, are assigned to the points then any automorphism carries this assignment over into a new one from which it is objectively indiscernible (to use Leibniz’s word). Hence any coordinate assignment requires an act of choice by which one picks out one from a class of equally admissible coordinate systems. The class is objectively characterized, but not the individual coordinate assignment. In Galois’ theory the “points” are the n roots α1, · · · , αn of an algebraic equation of degree n with rational coefficients. The objective relations are those expressible in terms of the fundamental operations of addition, multiplication, subtraction, and division, i.e., all relations of the form F(α1, · · · , αn) = 0 where F(x1, · · · , xn) is a polynomial of the n variables x1, · · · , xn, with rational coefficients. Labeling the roots by 1, 2, · · · , n amounts to a coordinate assignment. A transformation is a permutation of the n roots, an automorphism a permutation which leaves all algebraic relations F(α1, · · · , αn) = 0 with rational coefficients undisturbed; the automorphisms form the Galois group. Examples from geometry are probably more familiar to this audience. In the three-dimensional Euclidean vector space a frame of reference consists of 3 mutually perpendicular vectors of length 1. Relative to such a frame any vector can be described by the triple of its coordinates (x1x2x3). Transition from one such frame to an arbitrary other is effected by an orthogonal transformation of the coordinates x1, x2, x3, and these transformations constitute the group of automorphisms. In affine vector geometry this group is replaced by the group of all homogeneous linear transformations with non-vanishing determinant (or, if one follows Euler, with determinant 1). In the first half of the nineteenth century projective geometry had arisen, whose group of automorphisms consists of all collineations, i.e., of all point transformations that carry straight lines into straight lines. Möbius had added his spherical geometry, the automorphisms of which carry spheres into spheres. In a space of three or more dimensions the group of Möbius transformations coincides with that of all conformal transformations. Ideas which seem to have guided Möbius implicitly in his investigations, but could not be formulated without the group concept, were made explicit by Felix Klein in his famous Erlanger program, 1872.1 Transitions between equally admissible coordinate assignments or frames of reference in a Klein space find their expression in a group Γ of coordinate transformations. Klein defines the geometry by this group, which the mathematician feels free to choose as he likes: point relations are then said to be of objective significance if they are invariant with respect to the group Γ, two configurations of points are considered objectively alike if one is carried into the other by an operation of the group. For instance, if the group is transitive, as we shall assume in the future, all points are alike, the space is homogeneous.

According to Einstein’s special relativity theory the four-dimensional world of the space-time points is a Klein space characterized by a definite group Γ; and that group is the one most familiar to the geometers, namely the group of Euclidean similarities—with one very important difference however. The orthogonal transformations, i.e., the homogeneous linear transformations which leave

unchanged have to be replaced by the Lorentz transformations leaving

invariant. This was certainly a surprise to the mathematicians. But it did not disturb them very greatly; Minkowski made the necessary adjustments at once. Indeed in algebraic geometry they had become used to considering their variables as capable of arbitrary complex values; for that made their theories so much simpler, owing to the fact that the field of all complex numbers is algebraically closed, i.e., that an arbitrary algebraic equation of degree n with coefficients in the field always has n roots in the field. Now in the domain of complex numbers there is no difference between (+) and (−); indeed (+) goes over into (−) by substituting ix4 for x4. But in the last forty-odd years algebra has reversed its position: not only has it recognized the right of the field of real numbers besides that of the complex numbers, but it carries on its investigations, whenever possible, in an arbitrarily given field of numbers, no longer assuming that this underlying field, though closed with respect to the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, be also algebraically closed. Two non-degenerate quadratic forms with coefficients in a given field ![]() belong to the same genus if one may be carried into the other by a linear transformation with coefficients in

belong to the same genus if one may be carried into the other by a linear transformation with coefficients in ![]() . Special relativity could have taught the algebraists this lesson: do not ignore other genera of quadratic forms besides the principal genus represented by the unit form

. Special relativity could have taught the algebraists this lesson: do not ignore other genera of quadratic forms besides the principal genus represented by the unit form ![]() . As a matter of fact, in their arithmetical theory of quadratic forms, a classic subject from Gauss to Minkowski, they had never ignored them. I am afraid, the geometers had. Yet one can hardly say that here the mathematicians received a new stimulus from relativity theory; rather Klein’s Erlanger program and the distinction of genera of quadratic forms was in happy concordance with relativity theory, and Einstein’s discovery gave support to these geometric and algebraic conceptions by exhibiting one very important and quite unexpected application in physics.

. As a matter of fact, in their arithmetical theory of quadratic forms, a classic subject from Gauss to Minkowski, they had never ignored them. I am afraid, the geometers had. Yet one can hardly say that here the mathematicians received a new stimulus from relativity theory; rather Klein’s Erlanger program and the distinction of genera of quadratic forms was in happy concordance with relativity theory, and Einstein’s discovery gave support to these geometric and algebraic conceptions by exhibiting one very important and quite unexpected application in physics.

We are used today to look at mathematical questions from the standpoints of abstract algebra and of topology. Between the orthogonal and the Lorentz group there is a topological difference much more incisive than the algebraic difference of genus: the one is a compact manifold, the other is not. The most systematic part of group theory deals with the representations of groups by linear transformations. Representations in a Hilbert space of finite or infinitely many dimensions are of supreme interest to quantum mechanics. If the group is finite every such representation breaks up into irreducible parts of finite dimensionality; the entire theory, one of the proudest buildings of mathematics, is dominated by the orthogonality and completeness relations. They carry over from finite to compact groups. The theory of Fourier series is nothing but the representation theory of the group of rotations of a circle. Pleased by the beauty and harmony of this theory of representations of compact groups, the mathematicians shyed away for some time from the more complicated and less harmonious situation that had to be expected for non-compact groups. But the Lorentz group and the interest which quantum mechanics has in its representations in Hilbert space finally forced the issue: V. Bargmann in this country and Gelfand and Neumark in Russia mustered enough courage to tackle the representations of the Lorentz group in Hilbert space, and the Russians went on to develop the theory for any groups that are locally but not globally compact.

There is hardly any doubt that for physics special relativity theory is of much greater consequence than the general theory.2 The reverse situation prevails with respect to mathematics: there special relativity theory had comparatively little, general relativity theory very considerable, influence, above all upon the development of a general scheme for differential geometry. The kind of world geometry Einstein needed to put into mathematical form his central idea of an inertial field that not only acts upon matter but is also acted upon by matter, he found ready-made in the mathematical literature: from Gauss’s theory of surfaces in Euclidean space Riemann had abstracted his conception of an n-dimensional Riemannian space. Here the coordinate assignment remains quite arbitrary, subject to arbitrary (differentiable) transformations. A coordinate system usually covers only a part of the manifold; a finite or even an infinite number of partially overlapping patches are needed to cover it completely. But this is of little concern to us, as long as we are still far from overlooking the four-dimensional world in its entire extension. The fact that in an infinitesimal neighborhood of a point Pythagoras’ theorem is supposed to prevail finds its expression in Riemann’s formula

for the square of the length ds of a line element that leads from the point P = (x1, · · · , xn) to an arbitrary infinitely near point P′ = (x1 + dx1, · · · , xn + dxn). The coefficients gij do not depend on the line element but will in general vary from point to point. Riemann had gone some distance in developing this kind of geometry, which clearly follows a trend entirely different from Klein’s Erlanger program; he had, in particular, derived what is now called the Riemann curvature tensor. An elaborate mathematical machinery for Riemannian geometry had been set up under the name of Absolute Differential Calculus by G. Ricci and T. Levi-Civita. These things, which Einstein learnt from his friend, the mathematician Marcel Grossman in Zurich, enabled him to write down the equation of motion for a planet and the differential equations for the gravitational field, without an appeal to experience, in a purely speculative and yet astonishingly compelling manner. And Nature graciously confirmed his laws with as clear an O.K. as one can ever get from her.

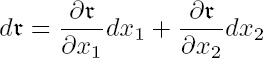

The great importance which Riemannian geometry acquired for Einstein’s theory of gravitation gave the impetus to develop this geometry further, to study more carefully its foundations and, as a consequence of such analysis, to generalize it in various directions. The first and decisive step was Levi-Civita’s discovery of the notion of infinitesimal parallel vector displacement. Let us begin with Gauss’ representation of a surface in Euclidean space. The points P of the surface are referred to arbitrary coordinates x1, x2, the location of the point P in the embedding space is given by r = r(x1x2) where ![]() is the vector leading in that space from the origin O to the space point P. The increment

is the vector leading in that space from the origin O to the space point P. The increment

is the line element joining P = (x1, x2) with the nearby surface point P′ = (x1 + dx1, x2 + dx2). In this way it comes about that the two-dimensional linear manifold of the tangent vectors r in P is referred to the affine vector basis consisting of the two vectors

![]()

The metric structure of this vector compass is taken into account, only afterwards, as it were, by expressing the square of the length of r as a quadratic form Σgijξiξj of its components with certain coefficients gij. Thus the two-dimensional Euclidean vector space, the compass at P, is here treated as an affine space to which a quadratic form is joined as the “absolute.” In a similar fashion affine space is sometimes treated as projective space in which one plane has been absolutely distinguished as the “plane at infinity.” There is an obvious artificiality in this procedure as it falsifies the group, so to speak; but it is also obvious how Gauss’ approach led to this treatment. But the natural frame for the compass would be a Cartesian one consisting of two perpendicular vectors ![]() of length 1 at the point P; choose such a frame without tying it to the coordinates x1, x2 to which the neighborhood P on the surface is referred. The line element

of length 1 at the point P; choose such a frame without tying it to the coordinates x1, x2 to which the neighborhood P on the surface is referred. The line element ![]() will then be given by an expression

will then be given by an expression ![]() where the ωi are linear differential forms oi1dx1 + oi2dx2. Invariance must prevail (1) with respect to arbitrary transformations of the coordinates xi, (2) with respect to an arbitrary rotation of the frame

where the ωi are linear differential forms oi1dx1 + oi2dx2. Invariance must prevail (1) with respect to arbitrary transformations of the coordinates xi, (2) with respect to an arbitrary rotation of the frame ![]() of the vector compass at P, arbitrary in the sense that it may depend in an arbitrary fashion on P. This scheme which E. Cartan always used is better suited to the nature of the Pythagorean metric. When one tries to fit Dirac’s theory of the electron into general relativity, it becomes imperative to adopt the Cartan method. For Dirac’s four ψ-components are relative to a Cartesian (or rather a Lorentz) frame.3 One knows how they transform under transition from one Lorentz frame to another (spin representation of the Lorentz group); but this law of transformation is of such a nature that it cannot be extended to arbitrary linear transformations mediating between affine frames.

of the vector compass at P, arbitrary in the sense that it may depend in an arbitrary fashion on P. This scheme which E. Cartan always used is better suited to the nature of the Pythagorean metric. When one tries to fit Dirac’s theory of the electron into general relativity, it becomes imperative to adopt the Cartan method. For Dirac’s four ψ-components are relative to a Cartesian (or rather a Lorentz) frame.3 One knows how they transform under transition from one Lorentz frame to another (spin representation of the Lorentz group); but this law of transformation is of such a nature that it cannot be extended to arbitrary linear transformations mediating between affine frames.

Let us return to the surface in Euclidean space. A tangent vector r at P can be transferred to the nearby surface point P′ by parallel displacement in the embedding Euclidean space. The r thus obtained is no longer tangential at P′; we therefore split it into its tangential and its (infinitesimal) normal component at P′, r = r′ + rn, and throw away the latter: r → r′ is Levi-Civita’s process of infinitesimal parallel displacement on the surface. It first looks as if it depended on the embedment of the surface into the surrounding Euclidean space; but when one carries out the computation, it turns out to be completely determined by the intrinsic metric of the surface. Hence it must be possible to give an intrinsic definition of the process. The first obvious property of Levi-Civita’s displacement is that it leaves the length of the vector r unchanged. In combination with another intrinsic condition, which I shall not formulate but only allude to by the word “condition of closure,” this leads indeed to a unique determination of the “affine connection” by virtue of which each vector at P goes over into a definite vector at the infinitely near point P′. After the notion is thus made independent of an embedding Euclidean space, it becomes applicable to any two-dimensional, nay to any n-dimensional Riemannian manifold.

It is natural to introduce the concept of an affinely connected manifold as one in which the process of infinitesimal parallel vector displacement satisfying the condition of closure is defined.4 It is a fact that the whole tensor analysis with its “covariant derivatives” makes use of the affine connection only, not of the metric. Also Riemann’s curvature finds its place here. Indeed if one carries the compass at P by successive steps of infinitesimal parallel displacement around a circuit returning to the start P, then the compass will in general not return to its initial position, but in one that arises from the initial position by a certain rotation around P. This rotation is essentially what Riemann called curvature and what should perhaps more appropriately be called vector vortex. The affine notions of covariant differentiation and of curvature become applicable to Riemannian geometry owing to the fact that the Riemann metric uniquely determines the affine connection.

Thus an affine infinitesimal geometry has sprung up beside Riemann’s metric one. One may say that the causal structure of the universe in the immediate neighborhood of the world point P is described by the equation Σgijdxidxj = 0. Hence a Riemannian metric gij and a metric ![]() of the same space lead to the same causal or conformal structure if

of the same space lead to the same causal or conformal structure if ![]() with a positive factor λ depending on P in an arbitrary fashion.5 Such features of a Riemannian space are conformal as are not affected by the change gij → λgij. One can also easily describe under what conditions two affine connections are equivalent in the sense that they lead to the same geodesics and thus to the same inertial or projective structure. What happens, one may further ask, when one replaces the geodesics by any families of curves of such nature that through every point in every direction there goes one of these lines? (General geometry of paths.)

with a positive factor λ depending on P in an arbitrary fashion.5 Such features of a Riemannian space are conformal as are not affected by the change gij → λgij. One can also easily describe under what conditions two affine connections are equivalent in the sense that they lead to the same geodesics and thus to the same inertial or projective structure. What happens, one may further ask, when one replaces the geodesics by any families of curves of such nature that through every point in every direction there goes one of these lines? (General geometry of paths.)

Now here is clearly rich food for mathematical research and ample opportunity for generalizations. Thus schools of differential geometers sprang up in the wake of general relativity. Here in Princeton Eisenhart and Veblen took the lead, Schouten in Holland. In France, E. Cartan’s fertile geometric imagination disclosed many new aspects of the subject.6 Some of their outstanding pupils are Tracy Thomas and J. M. Thomas in Princeton, van Dantzig in Holland and Shiing Shen Chern of the Paris school. A lone wolf in Zurich, Hermann Weyl, also busied himself in this field; unforunately he was all too prone to mix up his mathematics with physical and philosophical speculations. In several ways these authors soon arrived at the conclusion that it is better to establish projective differential geometry not by abstraction from the affine brand, as described above, but independently, namely by associating with each point P of the manifold a projective space ΣP in the sense of Poncelet and Plücker, this homogeneous space taking the place of the affine vector compass in the affinely connected manifold. In the same manner a general conformal geometry may be developed by associating with each point P a Möbius space ΣP. The generalization is evident. Let a manifold M and a homogeneous Klein space Σ, defined by a transitive group Γ of transformations, be given. Assume that with each point P there is associated a copy ΣP of the Klein space, and that ΣP is carried over to the space ΣP associated with an infinitely near point P′ of M by an infinitesimal operation of the group Γ that depends linearly on the relative coordinates dxi of P with respect to P. The manifold M, or at least part of it, is referred to coordinates xi. In each ΣP we must choose an admissible frame of reference, with respect to which the points of ΣP are represented by coordinates ξ. Since the Klein space is supposed to generalize the affine tangent vector space, it is natural to assume that a definite center O in ΣP is marked which “covers” the point P on M. The frame for ΣP may be so chosen that O becomes the origin ξ1 = ξ2 = · · · = 0. It is further natural to assume that the infinitesimal vectors issuing from O in ΣP on the one hand, and those issuing from P in M on the other hand, are “in coverage” by dint of a one-to-one linear mapping. This assumption brings it about that Σ has the same number of dimensions as M. It is further natural to assume that, if the infinitesimal vector ![]() in ΣP covers

in ΣP covers ![]() on M, then the displacement ΣP → ΣP will carry O1 into the center O′ of ΣP′. But no other restrictions should be imposed. Carrying ΣP by successive steps of infinitesimal displacement around a circuit we shall, when we return to P, have arrived at a definite mapping of ΣP into itself, an operation of the Klein group that is independent of the choice of coordinates xi and also, if this is understood in the proper sense, of the choice of admissible frames in all the Klein spaces associated with the various points of M. It will, of course, depend on the circuit described. This automorphism is the generalization of Riemann’s curvature. Hence we have here before us the natural general basis on which that notion rests. The infinitesimal trend in geometry initiated by Gauss’s theory of curved surfaces now merges with that other line of thought that culminated in Klein’s Erlanger program.

on M, then the displacement ΣP → ΣP will carry O1 into the center O′ of ΣP′. But no other restrictions should be imposed. Carrying ΣP by successive steps of infinitesimal displacement around a circuit we shall, when we return to P, have arrived at a definite mapping of ΣP into itself, an operation of the Klein group that is independent of the choice of coordinates xi and also, if this is understood in the proper sense, of the choice of admissible frames in all the Klein spaces associated with the various points of M. It will, of course, depend on the circuit described. This automorphism is the generalization of Riemann’s curvature. Hence we have here before us the natural general basis on which that notion rests. The infinitesimal trend in geometry initiated by Gauss’s theory of curved surfaces now merges with that other line of thought that culminated in Klein’s Erlanger program.

It is not advisable to bind the frame of reference in ΣP to the coordinates xi covering the neighborhood of P in M. In this respect the old treatment of affinely connected manifolds is misleading. What I said about Cartan’s method in dealing with Riemannian geometry was intended as an illustration of this lesson. In studying curves in three-dimensional Euclidean space one does not use a stationary Cartesian frame but associates with the point P traveling along the curve a mobile frame that is adapted to the curve in the most intimate manner, namely the Cartesian frame consisting of tangent, principal normal, and binormal. Freedom means adaptability. Cartan coined the phrase méthode de répère mobile for this procedure. Also in the modern development of infinitesimal geometry in the large, where it combines with topology and the associated Klein spaces appear under the name of fibres, it has been found best to keep the répères, the frames of the fibre spaces, independent of the coordinates of the underlying manifold.

The temptation is great to mention here some of the endeavors that have been made to utilize these more general geometries for setting up unified field theories encompassing the electromagnetic field beside the gravitational one or even including not only the photons but also the electrons, nucleons, mesons, and whatnot. I shall not succumb to that temptation.

Nobody can predict what sort of geometric structures may be thought up, and hence it would be foolish to claim that our pattern of associated Klein spaces and their displacement is universal. Whatever the structure, it must be described in some arithmetical way relative to a frame of reference f, whether that frame consists of a coordinate system for the manifold M or of a coordinate system for M plus admissible frames of references for each associated Klein space, or is something even more complicated. Always the problem of equivalence arises, i.e., the question under what conditions two such structures can be carried into each other by a change of the universal frame f. It was in the attempt of solving this problem for Riemannian geometry that Christoffel first introtuced his 3-indices symbols which later were interpreted by Levi-Civita as describing infinitesimal vector displacement, and that Riemann constructed his curvature tensor. This example is typical. In a number of important cases the attempt of solving the equivalence problem led to associating Klein spaces with the points of the manifold and to defining their infinitesimal displacement. Auxiliary variables that had to be introduced could be interpreted as coordinates in the fibre space ΣP. Hence in practice the scheme has proved of fairly universal applicability.

I wish to say a word about Cartan’s treatment of Riemannian geometry. At each point P of the manifold the vector compass bears a Cartesian frame![]() . The infinitesimal vector

. The infinitesimal vector ![]() at P is expressed in terms of it,

at P is expressed in terms of it,

by means of coefficients ωi that are linear differential forms of the dxi. Passing from P to the near-by point P′ we obtain two Cartesian frames at P′: the one that is associated with P′ and the one into which the frame associated with P goes over by parallel displacement from P to P′. These two frames in P′ are linked by an infinitesimal rotation

the coefficients ωij of which are again linear differential forms. The displacement of the vector compass is now described by (1), (2). The condition of closure, which I never formulated, makes the ωij expressible in terms of the ωi. The adequate instrument for carrying out the calculations to which such a set-up inevitably leads is a calculus fully developed by Cartan; it deals with multilinear differential forms and their multiplication and “external” derivation. This is a subject of considerable importance in several branches of mathematics including topology.

A scalar f(x1, · · · , xn) has a differential ![]() . From an arbitrary linear differential φ = Σk φkdxk we can formally derive

. From an arbitrary linear differential φ = Σk φkdxk we can formally derive ![]() . The essential point now is that in interpreting this formal expression one assumes the antisymmetric rule dxkdxi = −dxidxk for the multiplication of the differentials dxi. It is then perhaps more sincere to introduce two independent line elements dx and δx and let dφ stand for the skew-symmetric bilinear differential form

. The essential point now is that in interpreting this formal expression one assumes the antisymmetric rule dxkdxi = −dxidxk for the multiplication of the differentials dxi. It is then perhaps more sincere to introduce two independent line elements dx and δx and let dφ stand for the skew-symmetric bilinear differential form

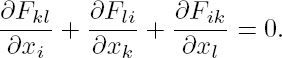

The marvelous thing about this kind of derivative is its invariance with respect to arbitrary coordinate transformations. If φ itself is the differential df of a scalar f, then dφ = 0: the derivative of a derivative is always zero. Maxwell’s theory of the electromagnetic field gives a perfect illustration for this calculus. The potentials φi form the coefficients of an invariant differential form φ = Σφidxi of rank 1; its derivative F = dφ, (3), of rank 2 gives the electromagnetic field strength ![]() . Since F itself is a derivative, the form dF of rank 3 must vanish, i.e.,

. Since F itself is a derivative, the form dF of rank 3 must vanish, i.e.,

The symbolism here employed is not as strange as it may strike you. Indeed look at the customary form of writing a double integral, ∫ · · · dx1dx2. Here also the proper meaning of dx1dx2 as the area of a parallelogram spanned by two line elements dx, δx would be more fully exhibited by writing it as the determinant dx1δx2 − dx2δx1; only this form indicates without explanation what happens to the integral under a transformation of coordinates. Multiplication of linear forms

![]()

must of course also be submitted to the antisymmetric rule dxkdxi = −dxidxk. It is clear how to pass on to higher ranks. All the integral theorems of vector and tensor analysis are special cases of the general Stokes formula which deals with the integral of a differential form of rank r over an r-dimensional (orientable) manifold imbedded in the space with the coordinates xi: the integral of the derivative df over a manifold C of dimensionality r + 1 equals the integral of f over the r-dimensional boundary ∂C of C. The law that the derivative of a derivative vanishes is thus the dual counterpart of the topological law that the boundary ∂C of something is always closed, i.e., has the boundary zero. The question whether a form f, the derivative of which vanishes, is itself a derivative leads straight to the topological theory of homologies and cohomologies; de Rham’s work is fundamental in that respect.

An impressive example demonstrating the power of this technique in which the méthode de répère mobile combines with the calculus of linear differential forms is a brief paper by Chern [1945], in which he gives an intrinsic proof for the analogue of the Gauss-Bonnet formula in a Riemannian space of arbitrary even dimension. The classical Gauss-Bonnet formula states for a closed surface in three-dimensional Euclidean space that the integral of its Gaussian curvature equals 2π · q where the even integer q is the most important topological invariant, the Euler characteristic. Allendoerfer had derived the formula for a Riemannian space of even dimension imbedded in Euclidean space, Chern freed it from the imbedding space.7 It is this perhaps the simplest instance of a relation between the differential and the topological properties of a space, and it seems that there are still many deep problems to solve in this field.

If one tries to understand what is behind the formal apparatus of tensor calculus that is used in general relativity, one arrives with necessity at the general notion of a covariant quantity. Let us take those transformations of the Klein space Σ mediating between admissible frames of reference which leave the center O of Σ fixed. They form a group Γ. A covariant quantity of definite type ![]() is described relative to an admissible frame f by a number of components X1, · · · , Xh which vary independently over all real values while the quantity ranges over the manifold of all its possible values. The components

is described relative to an admissible frame f by a number of components X1, · · · , Xh which vary independently over all real values while the quantity ranges over the manifold of all its possible values. The components ![]() of the same quantity relative to another admissible frame f′ are connected with the Xi by a linear transformation

of the same quantity relative to another admissible frame f′ are connected with the Xi by a linear transformation ![]() the coefficients tij of which are determined by the operation S of the group Γ that carries f into f′ . Composition of the group elements S must be reflected in the composition of the corresponding linear transformations ||tij(S)|| . We then speak of a representation of the group Γ by linear subsitutions, and that representation defines the type

the coefficients tij of which are determined by the operation S of the group Γ that carries f into f′ . Composition of the group elements S must be reflected in the composition of the corresponding linear transformations ||tij(S)|| . We then speak of a representation of the group Γ by linear subsitutions, and that representation defines the type ![]() of the covariant quantity. In the last decades a quite elaborate theory of representations of continuous Lie groups has developed, in which algebraic, differential, and integral methods are blended with each other in a fascinating manner. Here those problems which according to Study’s complaint the relativists had let go by the board are attacked on a much deeper level than the formalistically minded Study had ever dreamt of. For the representations of the linear group the symmetry characters studied in A. Young’s Quantitative Analysis and in a different manner by G. Frobenius, proved of great importance. Their bearing upon the quantum mechanics of systems consisting of equal particles (e.g., electrons) has been disclosed by Wigner. For the orthogonal group Cartan found a host of double-valued irreducible representations not less numerous than the single-valued ones. Their appearance is due to the topological fact that the orthogonal group is not simply connected but has a simply connected covering manifold of two sheets extending over it without boundaries and ramifications. The most elementary of these double-valued representations is the spin representation which Dirac used in his Lorentz-invariant quantum theory of the electron.

of the covariant quantity. In the last decades a quite elaborate theory of representations of continuous Lie groups has developed, in which algebraic, differential, and integral methods are blended with each other in a fascinating manner. Here those problems which according to Study’s complaint the relativists had let go by the board are attacked on a much deeper level than the formalistically minded Study had ever dreamt of. For the representations of the linear group the symmetry characters studied in A. Young’s Quantitative Analysis and in a different manner by G. Frobenius, proved of great importance. Their bearing upon the quantum mechanics of systems consisting of equal particles (e.g., electrons) has been disclosed by Wigner. For the orthogonal group Cartan found a host of double-valued irreducible representations not less numerous than the single-valued ones. Their appearance is due to the topological fact that the orthogonal group is not simply connected but has a simply connected covering manifold of two sheets extending over it without boundaries and ramifications. The most elementary of these double-valued representations is the spin representation which Dirac used in his Lorentz-invariant quantum theory of the electron.

Of course it would be foolish to maintain that all these investigations have their origin in relativity theory. Indeed Frobenius and Issai Schur’s spadework on finite and compact groups and Cartan’s early work on semi-simple Lie groups and their representations had nothing to do with it. But for myself I can say that the wish to understand what really is the mathematical substance behind the formal apparatus of relativity theory led me to the study of representations and invariants of groups; and my experience in this regard is probably not unique.

What is the upshot of it all? Relativity theory is intimately intertwined with a number of important branches of mathematics. Its influence in mathematics has been far less revolutionary than in physics and the epistemology of natural science; for its pattern fitted perfectly into the pattern of ideas already current in mathematics. But just because it could be absorbed so readily by mathematics it has stimulated the development and elaboration of those mathematical ideas to which it had a natural affinity.

[Weyl prepared this lecture for a celebration at the Institute for Advanced Study marking the seventieth birthday of Einstein, March 19, 1949; it was published in Weyl 1949b and WGA 4:394–400.]

1 [Regarding the Erlangen program (which Weyl here calls Erlanger), see above 66.]

2 [In 1949, many physicists considered general relativity a purely theoretical subject, important for cosmology, but not having any feasible experimental tests. That began to change with the experiments of R. V. Pound, G. A. Rebka, and J. L. Snider (Pound and Rebka 1959), which demonstrated the gravitational red-shift in a terrestrial experiment using the Mössbauer effect.]

3 [In contrast to Einstein’s well-known resistance to the quantum theory, Weyl was very open to it and continued to work on applying his gauge field ideas to Dirac spinors. Weyl 1929a, b introduced the tetrad or vierbein formulation of general relativity, meant to facilitate its connection with the Dirac theory.]

4 [Weyl 1952a, 112–117, 124–125, discusses affine manifolds in detail.]

5 [Weyl discusses the implications of conformal invariance for the dimensionality of space-time below, 212–213.]

6 [Weyl 1929c discusses the relation of his work and Cartan’s, continued in Brauer and Weyl 1935. Einstein was very interested in Cartan and corresponded with him on mathematical extensions of general relativity; see Cartan 1931, 1983, 1986, Pesic 2007, 179–186, and Cartan and Einstein 1979. For Weyl’s relation to Cartan, see Scholz 2010.]

7 As a matter of fact, before him Allendoerfer and A. Weil had given a proof by embedding each of the cells into which the space is cut up into a Euclidean space. Chern got rid of this embedding device.