Chapter 3

TEXT TALK

Engaging Readers in Purposeful Discussions

DOT McELHONE

Even in an increasingly digital world that offers us opportunities to engage in online discussions of a wide range of multimedia texts (Kissel, Wood, Stover, & Heintschel, 2013), face-to-face classroom discussions are increasingly important. Students need to develop interpersonal skills to help them navigate in-person social interactions. They need opportunities to develop their ideas about texts and to rehearse their writing through meaningful talk. To authentically assess student comprehension and thinking about texts, teachers need opportunities to listen in on student discussions.

Kris Hammond aims to give her students opportunities to talk “long and windingly” about their ideas and responses to texts. She engages students in whole-class discussions of read-aloud texts, organizes students into small book clubs where they share ideas and build interpretations with peers, and meets with them in individual and small-group reading conferences to discuss the texts they have chosen. Through face-to-face interactions in each of these contexts, Ms. Hammond comes to know each student both as an individual and as a reader in ways that inform and guide her teaching far better than any screening assessment could.

Reading is a social, cultural process, and talk is a crucial tool for comprehending, learning from, synthesizing across, and generating new ideas with texts, which are central demands of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010). Talk is not merely a medium that students can use to show what they know; by talking out their ideas and confusions with peers and teachers, students actually transform and deepen their thinking. In short, when students reason together through talk, they learn. When Ms. Hammond’s students talk at length about texts in student-led and teacher-led contexts, they use talk to reason and respond together and to grow as readers.

What Kind of Student Talk Promotes Learning?

Most of us who have spent time in classrooms have experienced moments of classroom text discussion that felt productive, engaging, and alive. We could almost see our students’ wheels turning—observe the learning happening before our eyes. There is a certain kind of fleeting magic in those moments, a magic that makes teaching and learning joyful and exciting, but that magic can be hard to re-create on a regular basis. What is it that makes those moments so special? How can teachers help them happen more regularly in the classroom? In this section, I explore the kinds of student talk that can make those moments glow and some ways to determine whether this is happening in your classroom. In the following section, I examine four practices that you can use to create more of these powerful moments.

If we could return to some of those magical classroom text discussions and look closely at what students were doing, we would probably find that they were excited about the text and their ideas. Perhaps they had “aha!” moments about how tornadoes and hurricanes work, about the nature of the fictional world in The Giver by Lois Lowry, or about the way calligraphy helps Ali cope as bombs fall over the city in Silent Music: A Story of Baghdad by James Rumford. Consider a time when there was a buzz of focused energy in the room. Students responded emotionally to the text and articulated new learning from it, perhaps “interrogating the text in search of the underlying arguments, assumptions, worldviews, or beliefs that can be inferred from [it]” (Soter et al., 2008, p. 374). They may have empathized with the difficulties faced by Sade and her brother after their they were forced to flee from Nigeria to England in The Other Side of Truth by Beverley Naidoo and challenged the beliefs and actions of the bullies in Sade’s new school. Students elaborated on their contributions by explaining them, offering reasons, or pointing to particular parts of the text. They went beyond the teacher’s interpretation of the text and offered surprising new perspectives.

These magical moments of discussion often have an exploratory quality (Barnes & Todd, 1995): Students explored ideas together by listening and responding directly to one another, building on and constructively challenging one another’s contributions, and working toward a consensus interpretation or answer. Collaborating toward consensus pushes students to reason together, rather than simply holding on to their initial impressions. Students might even reconsider or question their beliefs through these powerful discussions (Pierce & Gilles, 2008). When students are talking in this way, they are often so engaged that the conversations spill over from reading time onto the playground or into the lunchroom.

Table 3.1 offers some questions that you might ask yourself about the student talk you hear during text discussions in your own classroom. Answering these questions can help you set goals for student text talk. This work will be even more worthwhile if you collaborate with a trusted colleague. For example, each teacher could videotape text discussions for a week and then select one or two video segments to share. You could view the segments and choose some of the questions in Table 3.1 to answer about each one. Revealing the video segments that puzzle or concern you may feel risky. It is crucial that both teachers agree to respond in a positive, respectful manner that honors the risk each is taking by sharing his or her practice. My collaboration with Teri Tilley, a fifth-grade teacher, was built on a foundation of trust and respect. As we investigated video recordings of text-based talk in her classroom, she found that our work together was most productive when she focused on video segments and topics that felt a little scary. Those conversations pushed her out of her comfort zone and into new insights about student talk.

Table 3.1

Questions to ask yourself about your students’ talk

- Who is participating? Who is silent?

- Do students offer expressive or emotional responses to the text?

- Do students articulate new learning from the text?

- Do students make critical inferences and judgments about the text?

- Do students communicate their points clearly?

- Do students use talk to try out ideas that might not be fully formed? (This kind of exploratory talk is often marked by hesitations and incomplete statements.)

- Do students connect their contributions to what came before, or does each contribution send the conversation in a new direction?

- Do students respond to one another’s ideas uncritically (e.g., not noticing when their idea contradicts the one that came before)? Do students challenge one another’s ideas in a respectful way?

- Do students elaborate on their ideas by explaining, giving reasons or examples, or pointing to evidence in the text?

- Do students collaborate to try to reach a consensus about questions or interpretations? (Collaborating toward consensus pushes students to reason together, rather than simply holding on to their initial impressions.)

Cultivating Powerful, Engaging Discussions

What can you do to help students reason together through talk in ways that promote engagement and learning? How can you re-create the magic of powerful discussions regularly in your classroom? In this section, I explore four key ways that you can help your students move toward these kinds of discussions. First, you need to set the stage by establishing a safe climate for risk taking and by helping students understand what they will be doing with talk and why. Next, think carefully about the kinds of questions and follow-ups you pose to students during discussions, but also recognize that engaging discussion rests on more than good questions. Third, offer students supported opportunities to engage in small-group text discussions. Last, but perhaps most important, ensure that text discussions are based on interesting texts that merit critical, thoughtful discussion.

Setting the Stage for Productive Talk

Exploratory, critical, constructive talk among students can only occur in a classroom climate where students feel respected and safe in taking risks. Teachers and students create that climate from the first day of school through relationship building and activities that set the tone for the classroom culture. (Visit the Responsive Classroom website for useful resources on developing a positive classroom climate: www.responsiveclassroom.org/.)

Even in a warm, safe, supportive classroom, the kinds of talk about texts that promote learning and growth do not just happen on a regular basis. Engaging students daily in powerful talk requires intentional, talk-focused work. Researchers and educators such as Mercer and Littleton (2007) and Nichols (2008) have observed that when students are asked to engage in conversations around academic tasks without talk-focused preparation, those conversations often stray off topic, fail to delve deep into the academic content, or do not include the constructive challenges that are characteristic of exploratory talk. If you have listened in on small groups of students at work, you will likely recognize this phenomenon. Students are talking to one another, but they don’t seem to be getting anywhere with their talk.

Although all children (except some with particular special needs) arrive at school using language successfully for a range of purposes and engaging in social interactions, we cannot expect children to know how to engage in focused, academically productive discussions or elaborated, exploratory talk unless we show them how and support them. We swim in a sea of talk so continuously that we can fail to pay attention to the “water.” Setting students up for success in text discussions requires you to focus explicit attention on how talk will unfold.

Constructing Ground Rules

You can set the stage for productive discussions by constructing ground rules about how talk will work in the classroom. Researchers recommend establishing clear norms for turn taking in class discussions, such as asking each student contributor to select the next speaker (Michaels, O’Connor, & Hall, 2010). The Thinking Together program (Mercer & Littleton, 2007) is organized around a set of ground rules designed to promote exploratory talk. I adapted these ground rules into student-friendly language:

- Everyone joins in.

- Explain why you think what you think.

- Listen to what others are saying and try to understand their points of view.

- Give others the chance to try out new ideas.

- You can respectfully disagree with someone else’s idea if you give reasons.

- You can respectfully disagree with someone else’s idea and offer a different idea.

- Let each person share their idea before you make a decision as a group. (adapted from Mercer & Dawes, 2008, p. 66)

You can work with your students to develop ground rules in their own words that get at these same ideas.

The Accountable Talk approach to classroom discourse is organized around three forms of accountability (Michaels, O’Connor, & Resnick, 2008). These forms are different from the accountability that we associate with high-stakes tests and teacher evaluation. First, students are accountable to the learning community, which means that they listen to one another attentively and respond respectfully. Second, students are accountable to accurate knowledge: They strive to provide accurate information, refer to resources to help them get their facts straight, and notice where they need more information. Finally, students are accountable to rigorous thinking or standards of reasoning: building coherent, defensible arguments supported by relevant, compelling evidence. These norms might form the basis for co-constructed ground rules written in student-friendly language.

Before generating a list of ground rules, engage students in activities that require collaboration and conversation. You might start by asking pairs of students to meet together to talk about a picture book, poem, short story, article, or other short text. After these conversations, help students reflect together about their talk. They might notice that not everyone gets an equal opportunity to participate, that sometimes the conversation strays far away from the text or task, or that participants sometimes disagree but don’t explain why. After engaging in cycles of collaborative activity and reflection on talk over the course of a few days, the students will be more prepared to co-construct ground rules with you that will support the exploratory, constructive talk that you are hoping for. (See Dawes, 2011, and Dawes and Sams, 2004, for more ideas about setting the stage for talk.)

Once ground rules are established, the teacher should follow them, along with the students. For example, if treating tentative ideas with respect is a ground rule, the teacher should not evaluate a student’s contribution of a partially formed or in-process idea offered during a discussion. The teacher should leave the door open for the class to continue developing the idea (e.g., “What do other people think about David’s idea?”).

Acknowledging Different Talk Norms

When we construct ground rules for talk with students and refer to them regularly, we help students talk to learn (rather than only to be social), we provide a shared reference about what is expected, and we make norms that often exist as implicit expectations clear and explicit for all students. Because the kinds of talk norms advocated by researchers such as Mercer, Michaels, and O’Connor (e.g., those listed previously) are similar to implicit talk norms among middle class, white populations or associated with the dominant culture, some scholars have cautioned against sanctioning them as class ground rules (e.g., Lambirth, 2006). The concern is that making these norms the official discourse of the classroom privileges them over other kinds of talk and may disenfranchise or alienate students who come from backgrounds with different talk norms. This is a valid and important concern.

I argue that shying away from ground rules or explicit attention to talk norms is not the best way to address this concern. Talk norms exist in every cultural setting, including every classroom, whether they are acknowledged or not. Leaving norms implicit and unacknowledged is likely to result in frustration or limited success for students whose talk patterns do not match the unstated norms of the classroom. Instead, I encourage you to explicitly explain and model the norms for academically productive talk and support and coach students as they try on those norms. It is also important to explicitly acknowledge that these norms do not represent the only way to speak “correctly” or to “be smart.” You can help students navigate successfully across the multiple spaces where they live and learn by drawing their attention to the various ways of talking and interacting that they use across a range of purposes and settings. Have students brainstorm the kinds of talk that they might use in particular settings, or even role-play talk in those settings and point out that we use talk for different purposes and in different ways in different places and with different people. All ways of talking are valid. Demystify academic talk by making clear what is expected and showing students how they can participate successfully. Doing so will help include and engage all students in the learning community.

Facilitating Powerful Teacher–Student Dialogue

Over the past several decades, the recommended role of the teacher in classroom dialogue has changed quite a bit. In the not too distant past, teacher–student exchanges like this one were the accepted norm:

|

Mr. Elmore: |

|

What did Corduroy lose on his overalls? Samantha? |

|

Samantha: |

|

A button. |

|

Mr. Elmore: |

|

Right! A button. |

In this interaction, Mr. Elmore has asked a question for which he has one correct answer in mind (initiation). Samantha produces the answer (response), and he evaluates her response as correct (evaluation/feedback). Exchanges like this are often referred to by the acronym IRE (initiation–response–evaluation) or IRF (initiation–response–feedback).

The trouble with teacher–student interactions like this one is that they can shut down dialogue and do not typically offer opportunities for students to explore or develop ideas. Recitation sequences like this put the teacher in the position of primary knower (Berry, 1981), the one person in the classroom who holds authoritative knowledge. Students are often left trying to identify the answer that the teacher is looking for, rather than using talk to grapple with big ideas.

To address these problems with IRE/IRF recitation, over the past several decades, scholars have put forward a number of alternate forms of questioning and responding to students during class discussion. For example, Nystrand (1997) recommends that teachers pose authentic questions (i.e., open-ended questions without predetermined answers) as a way to promote dialogue. Mr. Elmore could have asked the class authentic questions about Corduroy by Don Freeman, such as, “Did you enjoy the story? Why or why not?” Some authentic questions challenge students to analyze, apply, synthesize, interpret, or evaluate what they have read. Mr. Elmore could have posed one of these higher order questions to prompt dialogue, such as, “What can you infer about the little girl from the ending of the story?” or “What would you have done if you were the girl?”

The Importance of Wait Time

To offer more students opportunities to think through the question and generate a response, Mr. Elmore would be wise to use wait time. Although keeping the overall pace of a lesson snappy is valuable, if we are seeking elaborated, thoughtful responses from students, we need to offer them time to think. That can feel awkward for teachers and students accustomed to rapid-fire recitation. I recommend addressing wait time in the ground rules for talk, setting an expectation that both the teacher and the students will offer others time to think. Explain to students why you do not call on the first student to raise a hand, and establish norms for wait time, such as keeping hands down until prompted by the teacher. Even three seconds of wait time between posing a question and calling on a student can dramatically increase the number of students participating in discussion. Once you have selected a student, it is valuable to offer further wait time. Students sometimes need to gather their thoughts during or before speaking. When you encourage other students to give the chosen student time to formulate his or her thoughts, you communicate that you respect your students and value thoughtful ideas over quick answers. This practice can be particularly valuable for English learners, who may need time to translate thoughts from their native language into English.

Taking Up Student Ideas and Pressing Students to Think Further

Authentic and higher order questions have the potential to open up dialogue about texts, but how should teachers respond after students answer these kinds of questions? Researchers have found that students offer more elaborated contributions to discussions when teachers do not evaluate student responses by saying things like “Good,” “Right,” or “Not quite” (Nystrand, 1997). By refraining from evaluation, you also step out of the role of primary knower and open space for students to be possible knowers (Aukerman, 2006): individuals with valid, worthwhile ideas to contribute. From these positions, students are able to reason together and grapple with ideas, rather than jockey for opportunities to report the “correct” answer. They can talk in ways that promote learning.

What should go in place of evaluation? Uptake, or incorporating a student’s response into a discussion (“taking up” their ideas), is a form of feedback that researchers recommend (Nystrand, 1997). High-press talk (McElhone, 2012), which is one form of uptake, involves probing student responses with follow-up questions that press them to take their ideas further. High-press follow-up questions ask students to clarify (e.g., “What do you mean?”), elaborate (e.g., “Can you say more about that?”), explain (e.g., “Why do you think so?” “How did you figure that out?”), provide evidence (e.g., “What did you see in the text that made you think that?”), or give examples (e.g., “Can you give an example?”).

Joy Nivera used this kind of feedback during a reading conference about Wilma Unlimited: How Wilma Rudolph Became the World’s Fastest Woman by Kathleen Krull (1996). This picture book chronicles the life of an African American track star and Olympic gold medalist who was struck with polio during her impoverished upbringing in the 1940s U.S. South. During a unit on biography and overcoming adversity, Ms. Nivera read this text aloud to her class. She discussed the challenges faced by Wilma with Gabriela.

|

1 Ms. Nivera: |

|

So, we’ve been talking about how in our biographies each—each person faced some diff—some struggles in their life. What have you noticed about Wilma and her struggles? |

|

2 Gabriela: |

|

That, um, that she struggled with, like, racism. |

|

3 Ms. Nivera: |

|

OK, with racism. So, back that up. What, uh, what is the evidence that she struggled with racism? |

|

4 Gabriela: |

|

’Cause they only had—like there were only a couple of doctors, and about the bus, too. |

|

5 Ms. Nivera: |

|

There were only a couple of doctors? |

|

6 Gabriela: |

|

Yeah. |

|

7 Ms. Nivera: |

|

Why were you thinking that had to do with racism? What made you say that’s about racism? |

|

8 Gabriela: |

|

Mostly the doctors, they wouldn’t help them because they were black, and the—the doctor they could go to lived a long way away. And on the bus to go over there, they had to ride in the back. |

|

9 Ms. Nivera: |

|

OK, so what does all that make you think about Wilma? |

|

10 Gabriela: |

|

It was hard, like it was already hard for her because she was sick, and they didn’t—they didn’t have a lot of money and stuff. And then they made it hard—harder for her because she was black. They made it harder for her to get better and be happy just because she was black. It’s not fair how they did that. And I can’t—I can’t believe that all happened and she still got to become a gold medal winner. |

One of the most striking things about this moment of classroom talk is the way Gabriela elaborated on her evolving thinking. She proposed that Wilma struggled with racism, and then explored and built on that idea over the course of the conversation, sometimes hesitating or offering partially formed ideas. In this exchange, Ms. Nivera helped Gabriela elaborate by asking her follow-up questions that pursued her claim about Wilma’s struggles. In turns 3, 7, and 9, Ms. Nivera asked high-press questions that pushed Gabriela to do more with the ideas that she had communicated.

The way you respond to student contributions in discussions shapes student engagement and opportunities to learn. By inquiring into their thinking, you can prompt students to engage with their own ideas about text and with the text itself. Your responses also tell students something about what reading is and about who they are and can become as readers and participants in class discussion. In this interaction, Ms. Nivera took Gabriela’s ideas seriously. She stuck with Gabriela’s thinking even when it was unclear exactly where she was headed. The follow-up moves that Ms. Nivera chose positioned Gabriela as a capable reader with worthwhile ideas. They also highlighted building ideas (rather than mastering discrete skills) as central to the practice of reading.

Beyond Teacher Questions: Taking a Dialogic Stance

Although we know that it can be useful for teachers to ask authentic, higher order, open-ended questions and to follow up by taking up students’ ideas and probing their thinking, there is more to creating magical moments of productive student talk than particular types of teacher questions. Sometimes higher order or open-ended questions fall flat; students offer one-word answers or don’t chime in at all. Sometimes a teacher can pose a series of closed-ended questions in an IRE structure that launches an engaging, constructive discussion.

Recent research points to the importance of the teacher’s overall instructional stance in shaping the way students receive and respond to particular forms of teacher questions and feedback. A teacher’s stance is informed by the purposes that he or she brings to classroom interactions over time. For example, a teacher concerned primarily with test preparation or eliciting correct answers, or who believes that students can simply listen and “receive” school knowledge without connecting it to their everyday knowledge, takes a monologic stance. The students in this class might notice that their teacher does not seem to really listen to their ideas, except to check whether they are correct. They get a sense that their job is to report correct answers as quickly as possible so the class can move on, and might offer only brief responses aimed at guessing what answer the teacher has in mind even when he or she poses an open-ended question.

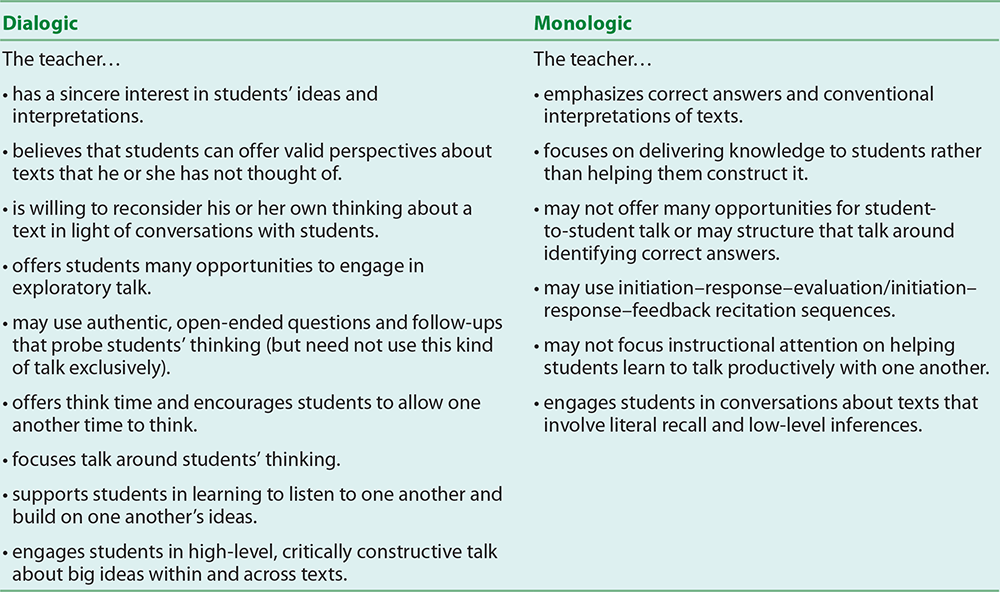

In contrast, Boyd and Markarian (2011) report on a third-grade teacher named Michael who brings to classroom conversations a sincere interest in his students’ ideas. He is, first and foremost, a listener. Over the course of the school year, Michael’s students pick up on his desire to hear them elaborate on their thinking and develop ideas about texts together, even when he poses closed-ended questions. Michael takes a dialogic stance toward his literacy teaching. In this dialogic classroom, students can read the undercurrent of the teacher’s intentions in his tone of voice, his focused way of listening to students, the think time he offers, and in the way he encourages students to add their thoughts, rather than always emphasizing his own. Table 3.2 shows a comparison of monologic and dialogic stances.

I find the research on monologic and dialogic stances encouraging. It tells me that although I should be thoughtful about the questions I pose and the way I respond to students, I don’t have to be perfect. If I maintain the genuine interest in getting to know students and learning about their ideas that drew me to teaching in the first place, and if I communicate that interest through words, gestures, and actions, my students are likely to understand that my classroom is a space where they can grow ideas and elaborate on them through talk. They are likely to pick up on my dialogic stance.

Table 3.2

Characteristics of dialogic and monologic stances

Navigating Across Communicative Approaches

Given today’s rigorous standards and the central role of high-stakes tests, taking a dialogic stance in teaching has become especially challenging. How can a dialogic teacher teach the content that students need to meet the standards? Does being a dialogic teacher mean never providing explanations or modeling for students? Must a dialogic teacher follow every interaction wherever it leads, even when conversation drifts far from the intended purposes of a lesson? Definitely not. In fact, Mortimer and Scott (2003) found that effective, dialogically oriented science teachers navigate across multiple communicative approaches for different instructional purposes.

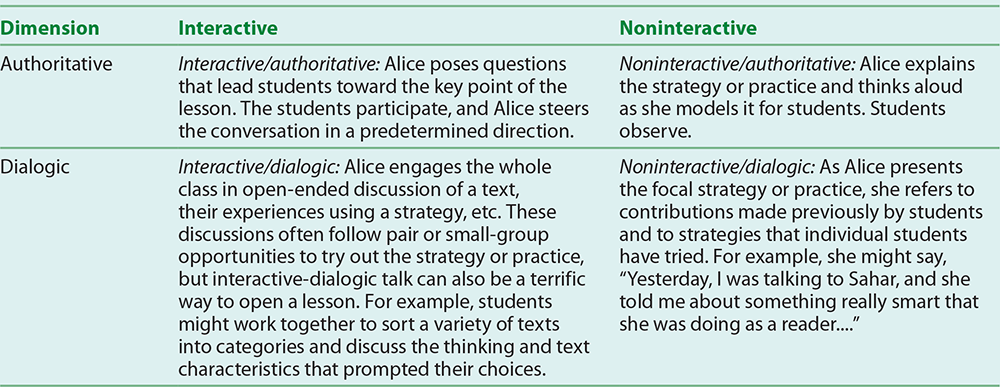

These researchers described communicative approaches across two dimensions: interactive–noninteractive and authoritative–dialogic. In interactive communication, students have opportunities to contribute to class discussion, whereas in noninteractive communication, the teacher does all of the talking. Authoritative communication occurs when the teacher steers the talk in a particular direction, such as to make an instructional point or to introduce a concept that students are unlikely to discover on their own. In dialogic communication, student ideas are incorporated into the flow of the talk, although they might be referred to by the teacher rather than spoken by the students. (The term dialogic is used a little differently in this context than in an overall dialogic stance.) These two scales yield four communicative approaches: interactive/authoritative, noninteractive/authoritative, interactive/dialogic, and noninteractive/dialogic. A skilled teacher can take an overall dialogic stance toward literacy teaching while navigating across these four communicative approaches. Table 3.3 summarizes Alice Pan’s use of the four communicative approaches during reading minilessons.

Table 3.3

How Alice Pan uses the four communicative approaches in her reading minilessons

By traversing these four communicative approaches, Alice can engage students in critically constructing ideas together and offer some explicit, formative assessment–driven teaching of strategies that will help students grow as readers. This class has a trajectory: It is clearly headed somewhere, but the journey isn’t rigid or lockstep. Alice and her students move forward together in a bumpy, dynamic, alive way that keeps everyone learning.

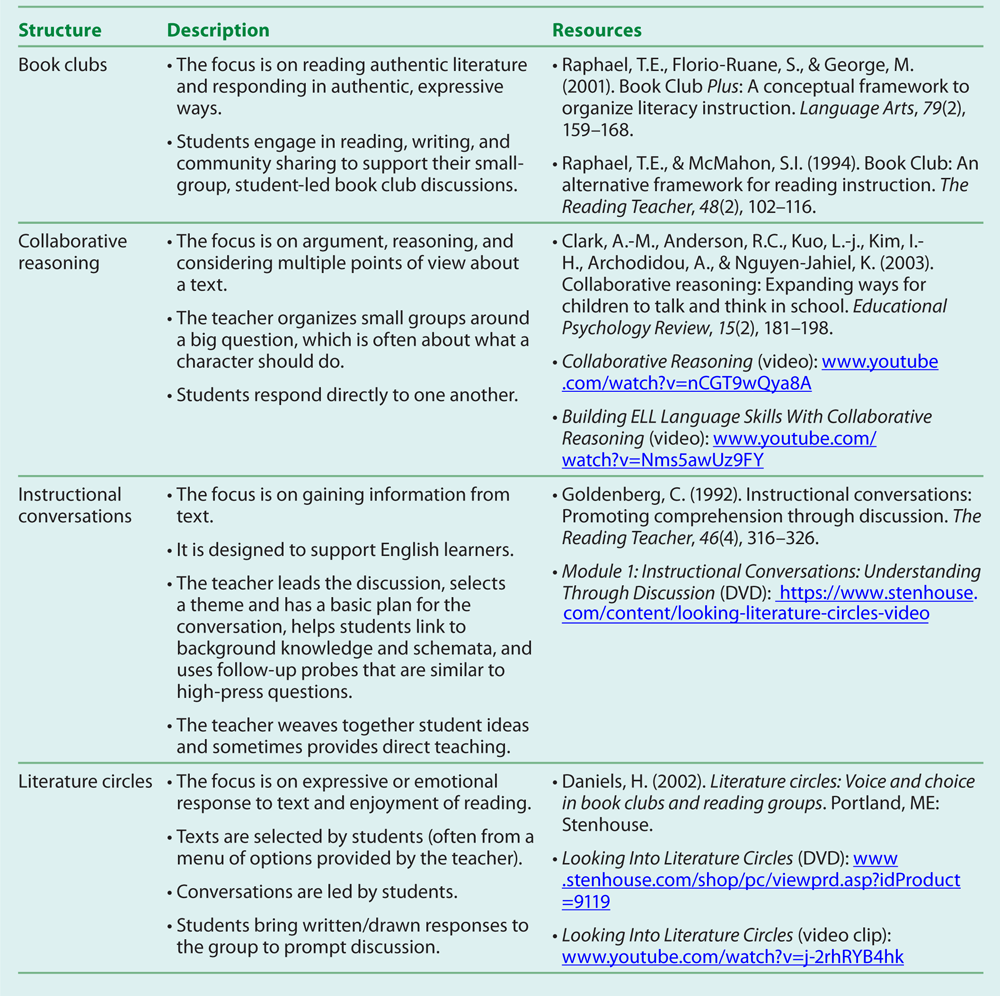

Scaffolding Productive Small-Group Text Discussions

If our goal is for students to build ideas about texts together through talk, our teaching must give them lots of opportunities to talk to one another. Book clubs (Raphael, Florio-Ruane, & George, 2001) and literature circles (Daniels, 2002) are examples of proven structures for discussion that are seeing a resurgence in light of the CCSS for speaking/listening and reading and as teachers push back against instructional practices and curricula that have parsed reading into a process of mastering discrete skill sets. Yet, literature circles and book clubs are not the only structures for engaging students in small-group text discussion. Table 3.4 provides resources to help you learn more about student-led and teacher-led small-group text discussion structures studied by researchers.

In any of these text discussion structures, the goal is for students to engage in enjoyable, constructive talk about texts. It’s important to guide students and scaffold their learning until they’re comfortable with such discussions. The teacher leads some structures (e.g., instructional conversations, Questioning the Author; see Beck & McKeown, 2006), whereas in others (e.g., literature circles), the teacher facilitates the classwide process, moves from group to group listening in on discussions, and occasionally offers a comment or idea, but the groups are run by the students.

Colleen Tracy assigns the group members in her class rotating roles, such as discussion director (facilitates the discussion) and passage picker (selects a favorite or puzzling passage to share and discuss with the group). She teaches minilessons about each role to help all students step into the discussion prepared. Many teachers have found these roles to be helpful, temporary scaffolds that support students as they learn to talk about texts together. However, be careful about relying on particular roles (or the role sheets that sometimes accompany them) for too long. Although using roles can encourage reluctant or uncertain students to start talking, over time the roles can constrain discussion. Conversation can become robotic: Each student reads the notes on his or her role sheet, and the discussion stops there.

Table 3.4

Selected structures for small-group text discussion

Some teachers, such as Ms. Hammond, find that students engage more effectively in small-group text discussions when they create more open-ended responses that aren’t tied to particular roles. In minilessons, Ms. Hammond teaches her students to try out various types of response and to track their thinking across a text using sticky notes. For example, students might track the author’s use of a particular symbol, jot down questions prompted by the text, or note similarities and differences in the content of two informational texts on the same topic. Ms. Hammond also teaches her students, many of whom are English learners, how to keep a discussion going and how to incorporate strategies for close reading and critical analysis of texts into their conversations. She models small-group discussions with students and occasionally with other teachers, and students have the opportunity to observe and comment on the kinds of talk they hear.

Within talk-focused minilessons, Ms. Hammond asks her students to try out posing particular kinds of questions to their partners, such as, “Where did you find that in the text?” She helps them get the language of text discussion “in their mouths” so they are more likely to use it when they collaborate in small groups without her direct guidance. The sticky note responses prompt students to tie their discussions to the text because they have to open it up to see the ideas they have written. That way, when students question one another or challenge one another’s ideas, they can point to specific text passages and investigate them together.

Literature circles typically focus on students’ emotional and expressive responses to texts, which are crucial aspects of the social process of reading. Ms. Hammond’s approach helps students respond emotionally and engage critically with texts in ways that are likely to help them meet the demands of the CCSS.

Choosing Texts That

Support Powerful Talk

For a text discussion to take on magical, alive, exploratory qualities, it must start with an interesting, compelling, or controversial text. Incorporating such texts may seem like a challenge if your school dictates strict use of narrow reading programs and decodable books. However, if you are hoping to convince your principal or district curriculum director of the importance of incorporating authentic, high-quality trade books, you can turn to CCSS Anchor Standard 10 (range of reading and level of text complexity; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010) for support. The CCSS call for students to read, comprehend, discuss, and connect ideas across increasingly complex, high-quality literary and informational texts. Some examples are provided in Appendix B of the CCSS. These lists can provide a starting point for thinking about appropriate texts, but don’t limit yourself and your students to the exemplar texts.

Seek out quality children’s literature across a range of genres and consider how you can incorporate a range of texts into your discussion activities with students. Award programs for children’s literature, such as the Coretta Scott King and Orbis Pictus awards, can offer a good starting point in identifying quality texts, although not all discussion-worthy texts are award winners. (See Table 3.5 for information about children’s literature awards.) You can also refer to the annual Children’s Choices booklists published by the International Reading Association. Young readers often have different tastes than adult judges, and their preferred texts may prompt the richest discussions. You might even host a children’s choice contest in your classroom and ask your students to vote for favorite texts in a number of different genres. Doing so is a terrific way to get to know your students as readers and to communicate to them that you value their opinions: one more way to take a dialogic stance in your teaching. Banned books and texts addressing social justice issues (see, e.g., www.tolerance.org/lesson/reading-social-justice) can also prompt engaging discussions that challenge students to question their thinking and beliefs.

Just as you hope your students will turn a critical eye toward texts in their classroom talk, it is important to ask critical questions as you select texts for whole-class discussion or as options for small-group discussion, such as, “Whose perspectives are represented in the text?” “Who is absent from the text?” and “What ways of knowing or ways of living are valued?” It is important to ensure that all of your students will see their cultural and linguistic backgrounds represented in the texts chosen for small- and whole-group discussion. Further, particularly if you teach in a relatively culturally homogeneous setting, make sure to incorporate texts into discussion that introduce your students to cultures and experiences that they might not encounter in their local surroundings.

Table 3.5

Selected children’s literature awards

- Batchelder Award for children’s books published outside the United States in a language other than English: www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/batchelderaward

- Caldecott Medal for illustrations in a picture book: www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/caldecottmedal/caldecottmedal

- Coretta Scott King Book Awards for African American authors and illustrators of books “that demonstrate an appreciation of African American culture and universal human values” (American Library Association, 2014, para. 1): www.ala.org/emiert/cskbookawards

- Edgar Awards for mystery (see the Best Juvenile category): www.theedgars.com/edgarsDB/index.php

- Jane Addams Award for children’s books “that effectively promote the cause of peace, social justice, world community, and the equality of the sexes and all races” (Jane Addams Peace Association, 2013, para. 1): www.janeaddamspeace.org/jacba/

- NCTE Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children: www.ncte.org/awards/poetry

- NCTE Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children: www.ncte.org/awards/orbispictus

- Newbery Medal for “the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children” (Association for Library Service to Children, 2014a, para.1): www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/newberymedal/newberymedal

- Pura Belpré Award for Latino/Latina authors and illustrators “whose work best portrays, affirms, and celebrates the Latino cultural experience” (Association for Library Service to Children, 2014b, para.1): www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/belpremedal

- Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Medal: www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/sibertmedal

- Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction: www.scottodell.com/pages/ScottO’DellAwardforHistoricalFiction.aspx

Choosing a face-to-face format for discussion doesn’t mean you cannot take advantage of digital resources. Powerful text discussions can emerge when students read e-books, blog posts, or informational or news-related websites.

Final Thoughts

Talk is the heart of classroom life and a powerful tool for learning, even in an increasingly digital age. As the pressure to meet rigorous standards mounts and the stakes around assessment grow ever higher, students need teachers to push back against policies and curricula that strip away the joyful, social, collaborative, critical nature of real reading. Whole-class, small-group, and one-on-one discussions of texts are crucial to students’ literacy development and to their success in meeting the CCSS. Teachers can help students engage in powerful, productive text talk by creating a safe climate for risk taking; developing, modeling, and scaffolding clear ground rules for participating in discussion; posing questions and follow-ups that encourage elaboration; taking a dialogic stance toward their literacy teaching; organizing small text discussion groups; and choosing texts that are likely to prompt rich discussion.

Classroom talk is both fascinating and complex. No teacher ever completely masters the art of engaging all students in powerful text discussions. There is always something new to learn. Consider collaborating with colleagues to use video as a tool for inquiring into the patterns of talk in your classroom. Perhaps the most important “what’s new” in classroom talk about texts will be what you uncover in your own reflective teaching.

References

American Library Association. (2014). The Coretta Scott King Book Awards. Available: www.ala.org/emiert/cskbookawards

Association for Library Service to Children. (2014a). Welcome to the Newbery Medal home page! Available: www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/newberymedal/newberymedal

Association for Library Service to Children. (2014b). Welcome to the Pura Belpré Award home page! Available: www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/belpremedal

Aukerman, M. (2006). Who’s afraid of the “big bad answer”? Educational Leadership, 64(2), 37–41.

Barnes, D., & Todd, F. (1995). Communication and learning revisited: Making meaning through talk. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Beck, I.L., & McKeown, M.G. (2006). Improving comprehension with Questioning the Author: A fresh and expanded view of a powerful approach. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Berry, M. (1981). Systemic linguistics and discourse analysis: A multilayered approach to exchange structure. In M. Coulthard & M. Montgomery (Eds.), Studies in discourse analysis (pp. 120–145). London, England: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Boyd, M.P., & Markarian, W.C. (2011). Dialogic teaching: Talk in service of a dialogic stance. Language and Education, 25(6), 515–534. doi:10.1080/09500782.2011.597861

Clark, A.-M., Anderson, R.C., Kuo, L.-j., Kim, I.-H., Archodidou, A., & Nguyen-Jahiel, K. (2003). Collaborative reasoning: Expanding ways for children to talk and think in school. Educational Psychology Review, 15(2), 181–198. doi:10.1023/A:1023429215151

Daniels, H. (2002). Literature circles: Voice and choice in book clubs and reading groups. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Dawes, L. (2011). Creating a speaking and listening classroom: Integrating talk for learning at key stage 2. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dawes, L., & Sams, C. (2004). Talk box: Speaking and listening activities for learning at key stage 1. New York, NY: David Fulton.

Goldenberg, C. (1992). Instructional conversations: Promoting comprehension through discussion. The Reading Teacher, 46(4), 316–326.

Jane Addams Peace Association. (2013). Awards home. Available: www.janeaddamspeace.org/jacba/

Kissel, B., Wood, K., Stover, K., & Heintschel, K. (2013). Digital discussions: Using Web 2.0 tools to communicate, collaborate, and create [IRA E-ssentials series]. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Lambirth, A. (2006). Challenging the laws of talk: Ground rules, social reproduction and the curriculum. Curriculum Journal, 17(1), 59–71.

McElhone, D. (2012). Tell us more: Reading comprehension, engagement, and conceptual press discourse. Reading Psychology, 33(6), 525–561. doi:10.1080/02702711.2011.561655

Mercer, N., & Dawes, L. (2008). The value of exploratory talk. In N. Mercer & S. Hodgkinson (Eds.), Exploring talk in school (pp. 55–72). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

Michaels, S., O’Connor, C., & Resnick, L.B. (2008). Deliberative discourse idealized and realized: Accountable talk in the classroom and in civic life. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27(4), 283–297. doi:10.1007/s11217-007-9071-1

Michaels, S., O’Connor, M.C., & Hall, M.W. (with Resnick, L.B.). (2010). Accountable Talk® sourcebook: For classroom conversation that works. Pittsburgh, PA: Institute for Learning, University of Pittsburgh.

Mortimer, E.F., & Scott, P.H. (2003). Meaning making in secondary science classrooms. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Authors.

Nichols, M. (2008). Talking about text: Guiding students to increase comprehension through purposeful talk. Huntington Beach, CA: Shell Education.

Nystrand, M. (with Gamoran, A., Kachur, R., & Prendergast, C.). (1997). Opening dialogue: Understanding the dynamics of language and learning in the English classroom. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Pierce, K.M., & Gilles, C. (2008). From exploratory talk to critical conversations. In N. Mercer & S. Hodgkinson (Eds.), Exploring talk in school (pp. 37–54). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Raphael, T.E., Florio-Ruane, S., & George, M. (2001). Book Club Plus: A conceptual framework to organize literacy instruction. Language Arts, 79(2), 159–168.

Raphael, T.E., & McMahon, S.I. (1994). Book Club: An alternative framework for reading instruction. The Reading Teacher, 48(2), 102–116.

Soter, A.O., Wilkinson, I.A., Murphy, P.K., Rudge, L., Reninger, K., & Edwards, M. (2008). What the discourse tells us: Talk and indicators of high-level comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(6), 372–391. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2009.01.001

Children’s Literature Cited

Krull, K. (1996). Wilma unlimited: How Wilma Rudolph became the world’s fastest woman. Orlando, FL: Harcourt.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

DOT MCELHONE is an assistant professor of curriculum and instruction in literacy at Portland State University in Portland, Oregon.