4

4 4

4

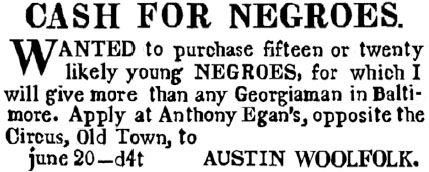

One of slave trader Austin Woolfolk’s early advertisements. Baltimore Patriot and Mercantile Advertiser, June 27, 1817.

CASH FOR NEGROES, shouted the advertisements that ran in the newspapers of Virginia and Maryland.

The ads were running as early as 1810, but the War of 1812 brought them to a temporary halt.1 After the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815 put a final victorious stamp on the war that had ended before the battle was fought, they proliferated as the economy began a ferocious expansion. An 1818 item in the New York—published National Advocate reports traders going around the streets of the Shenandoah Valley town of Winchester, Virginia, with labels reading CASH FOR NEGROES displayed on their hats.

There was always a market for “Negroes” in an expanding country of uncleared agricultural land. The key word was “cash.” Slave traders dealt in cash, which could mean specie (silver or gold coins) but typically meant high-quality paper that could be readily exchanged for specie. That made their offers compelling in an environment where “money”—almost always meaning not coins, but credit—was otherwise hard to come by. In the antebellum plantation economy, slaves were far and away the easiest property to convert to cash that a farmer might have; when a crop failed or prices dived, slaveowners could cover their debts by selling some of their laborers. Land, by contrast, had little cash value. Traders often sold slaves on time-payment plans, but they paid cash when buying, so they were important financial intermediaries in the Southern agricultural economy, dispensing liquidity as they bought children and enlarging the overall supply of credit—which was to say, of money—through the terms they gave their customers. In other words, staple crops were a credit business, but slaves were a cash business; the Southern economy was the result of the way the two worked together.

As the United States threw itself into what has been retroactively called the “market revolution,” transitioning from commerce based on imports to an ever more broadly based domestic market of producers and consumers, the domestic slave trade was the expression of that movement in the South. Addressing the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839, Connecticut abolitionist Henry Stanton used the common business-textbook metaphor of cash flow as blood circulation to describe the system that carried human chattels from the Upper South to the expanding Deep South: “The internal slave trade is the great jugular vein of slavery; and if Congress [would] … cut this vein, slavery would die of starvation in the southern, and of apoplexy in the northern slave states.”2

The rest of the world was well aware of this commerce. Writing in Die Presse of Vienna on October 25, 1861, the former New York Daily Tribune columnist Karl Marx noted “the transformation of states like Maryland and Virginia, which formerly employed slaves on the production of export articles, into states which raised slaves in order to export these slaves into the deep South.”3

We can’t quantify the domestic slave trade with any certainty, but we have a rough idea. Local transactions, not interstate trades, were likely the majority of slave sales; Stephen Deyle believes that at least two million people were sold in all, two-thirds of them in local transactions.4 Tadman declines to put a total number on the interstate trade, but based on Tadman’s work Deyle estimates that during the four decades or so prior to the end of slavery in the United States at least 875,000 enslaved people were taken southward, 60 to 70 percent of them trafficked in commercial transactions and the rest brought as a consequence of planter migration.5 More anecdotally, Illinois-born Frederic Bancroft, the path-breaking historian of the domestic slave trade, wrote in 1921 of trips he took to the “Southwest” in 1902 and 1907: “I made it my business to inquire of every ex-slave I met as to how he or she came South, if not a native. In fully four cases out of five, they were brought literally by the traders.”6

The southward trafficking of domestically raised slaves from what we will call the Upper South (Chesapeake and inland) and the Lower South (Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia) down into the “Southwest,” or Deep South (western Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas), accompanied by a flow of money in the opposite direction, bound these distinct geographical regions together into a commercial circuit that made it possible to speak of “the South” as a single entity.

That in turn led members of the Southern elite to imagine themselves leaders of a nation built on the economic system of slavery, which thrived with a balance of cash crops and human property value. In the widely reproduced March 1861 words of Alexander Hamilton Stephens, the exultant, newly named vice president of the Confederate States of America, slavery was “the chief stone of the corner in our new edifice.”7

Antebellum slavery was, in Gavin Wright’s essential phrase, “a set of property rights.”8 In a collision of the ancient institution of slavery with free-market capitalism, the modern nineteenth-century American slavery industry made laborers into financial products: merchandise, cash, productive capital, collateral, and, even, at the end of the chain, bonds.

Besides working for the people who legally owned them, the enslaved could be “hired”—rented—out, generating an income stream that could pay off a mortgage on them. “Negroes are a kind of capital which is loaned out at a high rate, and one often meets with people who have no plantation, but who keep negroes to let and receive very handsome sums for them every month,” wrote a German visitor to Savannah in 1860.9 Enslaved children were often rented out, among them Frederick Douglass.

But revenue from slave labor was only part of the profitability of slavery. Selling slaves was part of the commerce at every little Southern junction. Most farmers who had slaves bought or sold them at one time or another. “In slavery, niggers and mules was white folk’s living,” recalled an unnamed formerly enslaved woman in Tennessee, who said that her former master “would sell his own children by slave women just like he would any others. Just since he was making money…. My mother sold for $1,000.”10

The most obvious method of profit-taking in the slave market was by selling one or a few people at a time, as a plantation’s younger captives came of age while working on the staple crop with which the farm was at least nominally identified. Typically that crop was tobacco, in the case of Virginia and Maryland; the twin industries of slave raising and tobacco raising went on as complements to each other, but slave raising was for many the more lucrative.

The sale of surplus laborers wasn’t as explosive a cash-flow generator as a bumper crop, but it was more dependable, and the profits were significant. Financial and legal historian Richard Holcombe Kilbourne Jr. writes that “slaves represented a huge store of highly liquid wealth that ensured the financial stability and viability of planting operations even after a succession of bad harvests, years of low prices, or both.”11 Meanwhile, the seller had the important social distinction of being a planter instead of a slave breeder.

But neither were slaves merely labor to be jobbed out and merchandise to be sold for cash; they were also collateral with which to generate credit. Planters were chronically indebted, perpetually a year behind. They lived on credit, financing their operations with loans to be paid off by next year’s crops. The security pledged for such arrangements was most commonly the planters’ slaves, who were seen by lenders as largely risk-free collateral, even as they provided the labor that made the crop. If the crop failed, the laborers could be seized and sold on the open market. Meanwhile, the debt they collateralized added to the wealth of the slaveholding South; it was bundled into bonds that were sold to investors in New York, London, and beyond.

The financialization of enslaved people made them fundamental to the economy of the credit-driven slave society. The value of slaves, said James Gholson in the great Virginia slavery debate of 1832, “regulate[s] the price of nearly all the property we possess.” Children born into slavery, blandly referred to as “increase,” were capital assets at birth. They were the only way a planter’s assets could grow as inexorably as his debts compounded.

With human capital shoring up balance sheets as collateral for mortgages in a heavily indebted society, reproductive potential was factored into the price of enslaved women as part of a farm’s value as assessed by creditors. A slaveholder wrote to Frederick Law Olmsted that “a breeding woman is worth from one-sixth to one-fourth more than one that does not breed”; the ratio would presumably have been higher had women not died in childbirth so frequently.12

“Planters mortgaged their plantations, livestock, and slaves,” writes Russell R. Menard of the colonial Lowcountry, “to expand their estates by purchasing additional land, livestock, and slaves.”13 Most of this value was in the slaves, who as human collateral were constantly exposed to the risk of sale away from their families and community.

That’s how Thomas Jefferson funded the renovation of Monticello, by mortgaging the labor force that did the work. After he died in debt, his laborers were sold at auction. Often the decision was out of the slaveowner’s hands. In Jefferson’s case, the bitter end took the form of an estate liquidation after his death, so he never saw the human consequences of his impractical showpiece mansion and his extravagantly acquisitive ways: families separated forever on the auction block.

Much like a house mortgaged to a bank today, mortgaged slaves were security for those who put up the money for the mortgage, to whom the slaves were “conveyed.” A mortgage financier might be a merchant, a church with an investment portfolio, a college, a bank, or, commonly, a wealthy individual with a large slavehold. A slave put up for sale had to be warranted not only of “good character” (not criminal-minded or rebellious) but “free of all incumbrance” (not already mortgaged).14 Slaveowners had physical possession of, and legal title to, the enslaved, but to speak only of the slaveowners is to underestimate how broad was the stakeholding.

It is common today to hear people protective of the antebellum legacy go on the defensive by pointing out that the North profited from slavery too.

Certainly people and businesses in the North profited from slavery. Northern slaveowners sold off slaves to the West Indies and the South as slavery was ending in their territories, cashing in and diffusing their black population southward, though the numbers were tiny compared with those of the Chesapeake. New York monopolized the shipping of plantation products across the Atlantic. Northern banks captured the credit and foreign exchange generated by slave-driven agriculture, and bought and resold bonds collateralized by slaves. Hartford insurance companies, including the still-existing Aetna, sold policies to slave shippers and slaveowners, as Lloyd’s of London had done before. After the African slave trade was declared piracy, Northern merchants illegally financed and equipped expeditions to supply industrial quantities of African captives to the plantations of Cuba and Brazil.

But the capital invested in the expansion of the agricultural South does not seem to have mostly come from the North. Slavery created its own distinct circuit in the American economy, since its most valuable commodity, slaves, had no value outside the slavery bloc. By the last three decades of slavery, the South was largely funding itself, or, as Kilbourne puts it, despite the “despair-filled declarations of Southern commercial boosters and conventions … most of the internal investment in the region was funded with savings that had been accumulated over several generations in numerous wealthy households throughout the Cotton Belt.”15 Those “savings” overwhelmingly took the form of slaves, who were the basis of this massive intra-Southern credit-circulation system.

The Constitution gave Congress the power to coin money but in 1804, when Jefferson annexed Louisiana, the only US coins in common circulation were copper pennies.16 There was a chronic shortage in the South of “Spanish dollars”—the silver pesos minted in Mexico, also known as “pieces of eight,” which were accepted as legal tender in the United States, because until the discovery of gold in California in 1848, there were no large money mines in the United States. What little specie there was in circulation before the Gold Rush was rapidly pulled to the centers of banking in the North and, especially in colonial days, was sucked across the ocean by the manufacturing and commercial heavyweight of the world, Britain. The workhorse of Southern commerce was bank-issued paper money, but it entailed the risk that the bank might fail and it lost its value with distance from the issuing bank.

Enslaved people were the savings accounts. In lieu of coin or trustworthy paper, people were money in the slaveholding South. Most economists will tell you, with variations in the wording, that three conditions must be met for a commodity to be considered money:

1) a means for conducting transactions (“medium of exchange”);

2) retention of its worth over time (“store of value”); and

3) a way to keep accounts (“unit of account”).17

Slaves easily fit the first two criteria. They were a unique kind of money—a “money thing,” economists today might call it. They weren’t a convenient medium of exchange the way coins were, but coin was rare and when no reliable bank paper was available for a transaction a store debt could be paid with a child, whether through transfer of ownership or hiring out. A slave might be handed over in lieu of a debt from a land purchase or lost to a cardshark as a thousand-dollar bet in a high-stakes game.

Slaves satisfied the second condition of being money as well. As a store of value, they were the most trusted form in which a slaveowner might save his money. They not only retained their value over time by maintaining their value through reproduction, but they increased that value by reproducing frequently, which is why slaveowners insisted on owning the children: people paid flesh-and-blood interest when they reproduced. This was a modern adaptation of an ancient concept, as David Graeber notes: “in many Mediterranean languages, Greek included, the word for ‘interest’ literally means ‘offspring.’”18 Frederic Bancroft wrote that:

A stock-raiser indifferent to enlarging his herd was not so rare nor so absurd as a large planter that did not count the annual births and values that grew with the slave children. This increase alone was conservatively estimated to yield a net annual profit of from five to eight per cent after deducting all losses from age, illness or death. And even careless and spendthrift planters had such a passion to increase the number of their slaves that this human interest was regularly added to the principal, and thus compounded. A slaveholder twenty-five years old having 40 slaves might reasonably hope, without buying any, to become the owner of 150, or perhaps 200, slaves by the time he reached the age of sixty.19

If people were money, children were interest. That’s why the rigidly enforced color-coded caste system of slavery offered no path to freedom even over multiple generations: no escape from the asset column could be permitted.

At first glance, it might seem that slaves didn’t satisfy the third condition of being money, a unit of account. They were not what economists call a “sovereign currency.” No government accepted them for taxes, duties, fines, licenses, or fees. That honor went to the dollar, a denomination that Thomas Jefferson had (in the absence of any domestic sources of silver) modeled on the Spanish dollar combined with a French-inspired decimal system of cents, all in pointed contradistinction to the British pounds-and-shillings system.20

But in another way, slaves were a unit of account. The white South kept score in slaves. A rule of thumb for estimating a Southerner’s wealth was the number of slaves he had. And, as we will discuss, the Constitution’s notorious three-fifths clause* was explicitly designed to allow the South to vote that kind of wealth, making slaves a unit of account for what was literally political capital.

But if slaves were a kind of money, they were a nonconvertible domestic money, usable only inside the slave-trade zone. New York merchants wouldn’t accept slaves in payment for manufactured goods from Britain. They did frequently become slaveowners via control of slaves pledged as collateral, but if slaves had to be seized in satisfaction of a debt, they could only be sold in the regions that used slave labor. Since slaves couldn’t be used in trade outside the area of their circulation, they defined the economy of the region where they were traded.

For a money to be continually valuable, it must at times be defended by the government, even if the government is not the issuer. That happened in the case of slavery; Southern politicians were obsessively dedicated to preserving the monetary value of slaves, culminating in the cataclysmic war that ended the slave economy.

Owning people entailed risk: the person claimed as property might die, escape, or rebel. Those possibilities were best absorbed by large fortunes; slave-holding, the ultimate in inequality, was dominated by the wealthy. But taking on risk was essential for those who wanted to grow their fortunes fast. The Southwest was a magnet for high-spirited gamblers, especially in the Jacksonian era of wildcat banks. Young men in the South wanted to get rich now, before they died of some fever or distemper, so they went into cotton, plunging into debt to buy as many slave laborers, plant as much acreage, and get as fast a return as possible, then plow the profits into more land and slaves. But cotton acreage could only expand as fast as labor could be acquired to clear and cultivate it.

The reason slaves could not legally be created equal was not merely that appropriating one hundred percent of their labor was wildly profitable. Nor was it the many forms of comfort and pleasure they afforded their owners, nor even the owners’ routinely expressed fear that if freed, the blacks would do to the whites what the whites had done to them.

It was that attributing fully human characteristics to the enslaved would have debased the coin of the Southern realm.

The four million enslaved in 1860 were not merely a labor force; they were the South’s capital stock. Fanny Kemble quoted the words of “a very distinguished Carolinian” in her 1838–39 journal: “I’ll tell you why abolition is impossible: because every healthy negro can fetch a thousand dollars in Charleston at this moment.”21

Whether a slave child was ever sold in the market or not, his or her birth created money, in the form of credit, so the growth to four million enslaved people was in itself an economic expansion. The bottleneck in the creation of this unique form of sentient money was the capitalized womb.

Large landowners often preferred a strategy of buying slaves whenever they could get a good deal but never selling, whereas smaller farmers were more likely to need to sell an enslaved adolescent for cash to a regional trader’s representative. The kingpin of the Jackson-era slave trade, Tennessean Isaac Franklin, grew his fortune by accumulating people, and then put the money they collateralized to work in the credit market of his place and time by lending to smaller fry, whose slaves were in turn pledged to him as collateral. An 1847 accounting of the deceased Franklin’s estate valued the infants Andrew, George, Eliza, Larienia, Little Ann, Cynderrilla, Betsy, Shadrach, Sylvia, Lewis Edward, Noah, Isaac, Randolph, Washington, William, another Isaac, Meshac, and Matilda, along with “an infant child of Tracy Butler,” at $75 each (more than $2,000 each in 2014 dollars). They were not being priced for immediate sale, but expertly appraised for estate valuation.22

Older slaves were depreciated. Minerva Granger, who had produced nine children while enslaved by Thomas Jefferson, was at the age of fifty-five appraised as being worth nothing.23 Historian Caitlin Rosenthal explains that planters “appraised their inventory [of slaves] at market value, compared that with its past market value to assess appreciation or depreciation, calculated an allowance for interest, and used this to determine their capital costs. In a sense they were marking slaves to market.”24 The on-paper value of a child increased as he or she survived and grew, picking up around the age of eight, when he or she could begin to do a day’s work. The price peaked in the late teens, when the full-grown laborer could do a long day’s work and be advertised for sale as a “likely young Negro.”

That now-archaic word “likely,” ubiquitous in slave sale advertisements, had a cluster of converging meanings: vigorous, strong, capable, good-looking, attractive, promising—in other words, likely to reproduce.

*Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, subsequently invalidated by the Thirteenth Amendment, allows for the counting of three-fifths of “persons bound to service,” i.e. slaves, in determining a state’s representation in the House of Representatives, and, by extension, in calculating representation in the electoral college.