5

5 5

5Common sense will tell us, that the consumption of a slave must be less than that of a free workman. The master cares not if his slave enjoy life, provided he do but live … even the soft impulse of sexual attraction is subject to the avaricious calculations of the master.1

CAPITAL IS USELESS IF it is not being put to work, and slaveholders in every era were diligent in extracting the maximum return from their human capital.

Slaves were not allowed to be idle. Black men, women, and adolescents worked long days under the punishing sun doing hard labor that would have killed a white man, or so said the white men who expropriated their labor. In cold weather, they shivered in the rain and froze their fingers in the ice and snow.

In the early days of Chesapeake colonization, working alongside indentured English, Scotch, and Irish paupers and convicts, the enslaved cut down the hardwoods, pulled up the stumps, turfed the slopes of the plantations, and manicured the grounds of the master’s estate. They plowed, planted, weeded, harvested, and cured tobacco, rolled it in hogsheads down to docks they had built, and loaded it onto boats that enslaved boatwrights had constructed, piloted by enslaved navigators.

They fired the bricks with which they built the great houses that they painted, maintained, and staffed. Enslaved laborers built the stone walls, the zigzagging “worm” fences, and the roads, barns, sheds, smokehouses, and cesspools, as well as the cabins where they lived, six or eight or ten to a room. They forged the decorative ironwork, made the furniture, and except for hoes, chains, and a few other items, they even made the tools they made everything else with. “Almost all the implements used on the plantation were made by the slaves,” recalled Louis Hughes. “Very few things were bought.”2

They were most commonly employed in repetitive monocrop farming, the kind that is most destructive to the land. Every future Confederate state except Virginia raised quantities of cotton, and there were regional monocrops of tobacco in the Chesapeake, rice in the Sea Islands and Tidewater of South Carolina and Georgia, and sugar in south Louisiana. From London, Karl Marx succinctly described the practice in an October 25, 1861, newspaper column:

The cultivation of the Southern export articles, cotton, tobacco, sugar, etc., carried on by slaves, is only remunerative as long as it is conducted with large gangs of slaves, on a mass scale and on wide expanses of a naturally fertile soil, that requires only simple labor. Intensive cultivation, which depends less on fertility of the soil than on investment of capital, intelligence and energy of labor, is contrary to the nature of slavery.3

On this matter, which was more or less conventional wisdom, Marx agreed with his ideological adversary the Economist, which had printed in 1859:

The truth is, that Slavery could only be profitable on rich, large, and sparsely populated soils. The profit it yields it can only yield while the first fertility of a soil is unexhausted, and, therefore, where land is unsettled, and the labour need not be of a very earnest or skilful kind.4

When utilized this way, slave laborers were known for being utterly unenthusiastic workers. In some plantation regimes, the work was deliberately kept heavy so as to leave the labor force too tired to revolt. A note accompanying a hoe on display at Edisto Island Museum explains: “Until after the Civil War, even large tracts of land on Edisto were cultivated primarily by slaves using hoes, not animal-drawn plows. With the natural increase in the slave population, it was considered ‘good management’ to keep the work force as busy as possible.”

Perhaps neither Marx nor the Economist realized that slaves’ labor was not only crude. They brought a wide variety of expertise to skilled work. Enslaved craftsmen were the artisan class of both the colonial and the antebellum South. They helped build the White House and the US Capitol. Their knowledge, together with the forced labor of enslaved muscle, transformed forest, bramble, and swamp into the Anglo-American idea of civilization.

Planters and merchants arranged for their particularly talented artisans to be taught special skills by European craftsmen, which had the side effect of establishing a knowledge base among the community of the enslaved. It enhanced their monetary value: slaves deemed to be “skilled” brought more money in the market for both renting-out and sale. They worked as mechanics and tradesmen, discouraging white tradesmen from immigrating. Skilled slaves did cabinetry, woodworking, ironworking, tailoring, dressmaking, and jewelry-making; they were usually better than white craftsmen, if only because white craftsmen, if they were any good, often quit their trade as quickly as possible to go into planting rather than compete economically with slaves, or bought a slave to do the work for them.

Knowledge from Africa was basic to planters’ fortunes, nowhere more than in the cultivation of rice. In the unhealthy marshes of the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia, teams of enslaved laborers with interconnecting jobs—specialized task labor, not gang labor like cotton—operated complex plantations they had built with skills that were unknown to Europeans. They did this mostly in the absence of the masters, who fled their plantations in mortal fear of disease during the hot months, leaving only an overseer to run an all-black plantation.

The great rice plantations of the Lowcountry could never have been built and staffed with free labor. No one would have done that work voluntarily. Attacked by clouds of stinging insects in rattlesnake-ridden swamps, the rice slaves built dams, dug miles of ditches, burned the ground cover in spectacular nocturnal conflagrations, pulverized the earth, spent their days standing barefoot and waist-high in foul-smelling stagnant water, hoed endless rows of rice, regulated how much of the heavier salt water versus how much of the lighter fresh water to allow into the sluice gates they had designed and built, chased away the thick flocks of migrating bobolinks that could devastate a crop, winnowed the rice in baskets they had woven according to African practice, pounded the husks off with African-style tall pestles in mortars, and cut and hauled wood to build the barrels with, while also raising or catching much of the food they ate.

The homes of the enslaved brought little comfort after the work day. Josiah Henson, who published several iterations of his autobiography—the bestselling of the slave narratives, because Henson was said to be the inspiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s character of Uncle Tom—recalled in the earliest (1849) and possibly most accurate version that:

Our lodging was in log huts, of a single small room, with no other floor than the trodden earth, in which ten or a dozen persons—men, women, and children—might sleep, but which could not protect them from dampness and cold, nor permit the existence of the common decencies of life. There were neither beds, nor furniture of any description—a blanket being the only addition to the dress of the day for protection from the chillness of the air or the earth. In these hovels were we penned at night, and fed by day; here were the children born, and the sick—neglected.5

Old age was especially miserable for the enslaved. When Jefferson’s slaves got too old to work, he routinely cut their rations in half.6 Aged slaves were a drag on a planter’s profits, at which point it was cheaper to turn them loose and let them die off premises. The Virginia code of 1849 provided a fine of fifty dollars for “any person who shall permit an insane, aged or infirm slave … to go at large without adequate provision for his support,” which perhaps attests to how common the practice was.7 Isaac Mason, born enslaved in 1822 in Kent County, Maryland, recalled in his memoir that

My grandfather, in consideration of his old age and the time being past for useful labor, was handsomely rewarded with his freedom, an old horse called the “old bay horse”—which was also past the stage of usefulness—and an old cart; but, alas! no home to live in or a place to shelter his head from the storm.8 (emphasis in original)

They labored and reproduced and died and were replaced, without retaining the proceeds of their labor for their own needs, while the people who claimed to be their owners generally spent as little as possible on their maintenance. Field laborers, who had little or no direct contact with the master and his family, wore rough, cheaply manufactured “negro shoes,” and covered their bodies with osnaburg, or “negro cloth,” of jute or flax, a little softer than burlap. George White of Lynchburg, Virginia, recalled that “Dat ole nigger-cloth was jus’ like needles when it was new. Never did have to scratch our back. Jus’ wiggle yo’ shoulders an’ yo’ back was scratched.”9 They perhaps, but not necessarily, got summer and winter varieties. “Do you recollect that you have not given your Negroes Summer clothing but twice in fifteen years past[?]” wrote Georgia Sea Island plantation manager Roswell King to his boss, Constitution framer and absentee gentleman farmer Pierce Butler, at Butler’s mansion in Philadelphia.10 Thomas Jefferson’s captives got one blanket per family every three years, but when Monticello was leased out during his presidency, an overseer failed to distribute blankets for five years.11

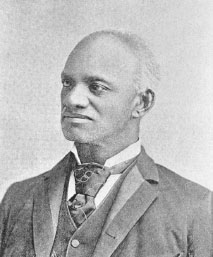

Isaac Mason’s author photograph.

They did hard labor in the same clothes all day, every day. When 225 enslaved people asserted their freedom by escaping into the custody of British rear admiral George Cockburn during his invasion of the Chesapeake in the War of 1812, Cockburn feared that the dirty rags they came clothed in might spread disease. He issued the men bright red jackets, which, said his commanding officer, Admiral Alexander Cochrane, might “act as an inducement to others to come off,” and he gave them military training, which they had previously been kept away from.12

Sometimes they worked without clothes at all. Enslaved children and sometimes even post-pubescent adolescents commonly were naked or barely clothed. Charles Ball recalled his first workday in a South Carolina cotton field after being trafficked from Virginia:

More than half of the gang were entirely naked. Several young girls, who had arrived at puberty, wearing only the livery with which nature had ornamented them, and a great number of lads, of an equal or superior age, appeared in the same costume…. [O]wing to the severe treatment I had endured whilst traveling in chains, and being compelled to sleep on the naked floor, without undressing myself, my clothes were quite worn out, I did not make a much better figure than my companions; though still I preserved the semblance of clothing so far, that it could be seen that my shirt and trowsers had once been distinct and separate garments.13

Denied basic hygiene, the laborers’ funk bothered masters enough to become a conversational commonplace among slaveholders, who typically attributed it to a racial characteristic, referring if necessary to Thomas Jefferson’s racist pseudo-factbook Notes on the State of Virginia: “they secrete less by the kidnies, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odour.”14

Enslaved women made the soap the slaveowner washed with. They carded, combed, spun, weaved, knitted, cut out, sewed, mended, washed, starched, and ironed the fine clothes the master’s family wore, and they worked into the night after a long day’s labor to dress their own families a little better, though at times there were difficult to enforce laws that forbade slaves from dressing above their station. Domestics, who were on display to guests, typically dressed much better than field laborers, often in hand-me-downs of the master or mistress.

In eighteenth-century Maryland, liveried coachmen drove the imported “chariots” in which the masters rode. In wealthy antebellum Mississippi, they wore velvet topcoats in the heat as they drove the masters’ barouches. Enslaved blacksmiths forged iron shoes for the horses that enslaved grooms put up at night. Enslaved fiddlers played at the Saturday night dances, and when the masters hunted foxes, enslaved houndsmen blew the hunting horns.

The enslaved brought to the masters’ table the food they supplied and prepared, and they kept everything the guests saw spotless, all on an unforgiving schedule. Urban slaves generally had a better diet than those on the plantations, and African Americans seem to have generally eaten better than slaves did on Antillean sugar plantations. But the quality and availability of food varied sharply from plantation to plantation, and most had an insufficient diet by modern standards.

The enslaved laborers who built the University of Virginia were fed the basic slave diet: greasy fat bacon and cornmeal, purchased in industrial quantities. A hogshead of bacon could weigh 900 pounds or more, and plantations bought commensurate quantities of molasses. “Some slaves enjoyed a wide variety of foods,” write Kenneth Kiple and Virginia King, “[but] others suffered from a seldom if ever supplemented hog-and-corn routine, while most existed on a basic meat-and-meal core with some supplementation.”15 That monotonous diet of “hominy and hog” was the mainstay for the enslaved, as well as for poor whites, in much of the South, though the enslaved of the Chesapeake and Lowcountry generally ate better than those in the Deep South. Unfortunately, the Southern-raised white corn, the most commonly eaten variety, contained no vitamin A.16 Milk was in short supply in the South, so the enslaved often got little or no calcium. They shocked doctors with their high rate of geophagy—eating clay or dirt, a malnutrition-related behavior especially associated with pregnant women—which caused a range of health problems.17 Arguing in favor of feeding the enslaved in a way he considered adequate, the overseer Roswell King Jr. of Butler Island, Georgia, wrote of the plantation’s 114 enslaved children in an 1828 letter published in the Southern Agriculturalist that “it cost less than two cents each per week, in giving them a feed of Ocra soup, with Pork, or a little Molasses or Hommony, or Small Rice. The great advantage is, that there is not a dirt-eater among them.”18

Black cooks knew how to work with the animal parts the master’s family didn’t want—the offal—and they also knew how to prepare grand Christmas feasts. It was common for the enslaved to tend a garden patch after a long day of work, and Sundays, usually a day off, could be spent hunting or fishing if owners allowed it. But even so, slaves were often malnourished and therefore sickly; the typical food expenditure for an enslaved laborer in Virginia was about a quarter that of a free laborer. Henry Watson, born in 1813 near Fredericksburg, Virginia, who was sold six times and whose experience was especially harsh, recalled the routine he knew in 1820s Mississippi:

In the morning, half an hour before daylight, the first horn was blown, at which the slaves arose and prepared themselves for work. At daylight another horn was blown, at which they all started in a run for the field, with the driver after them, carrying their provisions for the day in buckets…. [They] worked until such time as the driver thought proper, when he would crack his whip two or three times, and they would eat their breakfasts, which consisted of strong, rancid pork, coarse corn bread, and water, which was brought to them by small children, who were not able to handle the hoe.

As soon as Harry, the driver, has finished his breakfast, they finish likewise, and hang up their buckets on the fence or trees, and to work they go, without one moment’s intermission until noon, when they take their dinner in the same manner as their breakfast; which done, they go again to work, continuing till dark. They then return to their cabins, and have a half hour to prepare their food for the next day, when the horn is again blown for bed. If any are found out of their cabins after this time, they are put in jail and kept till morning, when they generally receive twenty-five or thirty lashes for their misdemeanor.19 (paragraphing added)

Charles Ball recalled a scene he witnessed while accompanying his master on travels in South Carolina:

After it was quite dark, the slaves came in from the cotton-field, and taking little notice of us, went into the kitchen, and each taking thence a pint of corn, proceeded to a little mill, which was nailed to a post in the yard, and there commenced the operation of grinding meal for their suppers, which were afterwards to be prepared by baking the meal into cakes at the fire.

The woman who was the mother of the three small children, was permitted to grind her allowance of corn first, and after her came the old man, and the others in succession. After the corn was converted into meal, each one kneaded it up with cold water into a thick dough, and raking away the ashes from a small space on the kitchen hearth, placed the dough, rolled up in green leaves, in the hollow, and covering it with hot embers, left it to be baked into bread, which was done in about half an hour.

These loaves constituted the only supper of the slaves belonging to this family for I observed that the two women who had waited at the table, after the supper of the white people was disposed of, also came with their corn to the mill on the post and ground their allowance like the others. They had not been permitted to taste even the fragments of the meal that they had cooked for their masters and mistresses.20 (paragraphing added)

Slave cabins did not have kitchens; cooking, if done indoors, was done in the fireplace. On some plantations children were fed out of troughs, eating with their hands or improvised spoons out of a communally served mush of corn-bread, molasses, or whatever else was customary.21

Beginning with maternal, fetal, and infant malnutrition, it’s hardly surprising that the enslaved were more susceptible than free people to most infirmities, including crib death, infant mortality of all kinds (including infanticide), death in childbirth, and injuries and deterioration to the mother from repeated childbirth, along with typhoid, cholera, smallpox, tetanus, worms, pellagra, scurvy, beriberi, kwashiorkor, rickets, diphtheria, pneumonia, tuberculosis, dental-related ailments, dysentery, bloody flux, and other bowel complaints. The health conditions of the enslaved were aggravated by overwork, accidents, and work-related illnesses such as “green tobacco sickness,” today known as nicotine poisoning, which plagued tobacco workers.22 The heavy work regimes they endured wore down their bodies and aged them prematurely, with childbirth-related fatalities limiting women’s life spans even more than the men’s.

The enslaved had a greater immunity to some diseases than the whites, though: the sickle-cell trait is believed to have evolved as a defense against malaria, to which many of the enslaved were immune, though they might become ill from sickle-cell disease. Some Africans were also immune to the yellow fever that on occasion killed large numbers of whites in fierce epidemics.

Africans brought a vast lore of medicines (and poisons) from Africa, and on occasion learned the use of local herbs and roots from the Native Americans. Attentive slaveowners learned from the medical knowledge of the enslaved, as in the case of smallpox vaccination, which spead in the hemisphere through the knowledge of Africans.23 In colonial Boston, Cotton Mather heard of smallpox vaccination from the enslaved Onesimus, whom Mather’s congregation had given him as a present: “Enquiring of my Negro-man Onesimus, who is a pretty Intelligent Fellow, Whether he had ever had ye Small-Pox he answered, both, Yes, and, No; and then told me, that he had undergone an Operation, which had given him something of ye Small-Pox, & would forever preserve him from it.” Onesimus had been vaccinated for the disease in Africa, and told Mather it was a common practice among the “Gurumantese” (Akan or Twi people of the Gold Coast, now called Ghana), “& who ever had ye Courage to use it, was forever free from ye fear of the Contagion. He described ye Operation to me, and shew’d me in his Arm ye Scar, which it had left upon him.”24

Especially in colonial days, slaveowners sometimes doubled as doctors. William Byrd II, the founder of Richmond, had a large medical library and gave his enslaved frequent “vomits” and “purges.” The enslaved were used as guinea pigs for experimental treatments that advanced the practice of medicine in the United States. An aspiring doctor or dentist in the South might buy an old or infirm slave to practice on. The nation’s first teaching hospital, at the Medical College in Charleston, used live enslaved people for demonstrations and dead ones for dissection. The “father” of modern gynecology, generally portrayed in medical historiography as an innovative figure, was the South Carolina surgeon J. Marion Sims, whom one historian refers to as “the Architect of the Vagina.” Sims refined his innovations by operating experimentally on the genitals of enslaved women he kept for that purpose. In this way, he developed a surgical repair for vesico-vaginal fistulas, using an infection-resistant silver suture, and more generally he popularized the use of surgery for gynecological problems, becoming quite wealthy in the process. In a “hospital” he built in his backyard in Montgomery, Alabama, he operated on a woman named Anarcha thirty times, sewing her insides without anesthesia and giving her opium afterward. He also kept women named Lucy and Betsy for this purpose, describing the expense of their maintenance as a research cost. After perfecting his treatment, he subsequently moved to New York, where he founded the Woman’s Hospital and continued experimenting surgically; since there was no slavery in New York, he practiced on poor Irish women, performing thirty surgeries on one Mary Smith.25

Later, there was an entire lucrative branch of “slave medicine” dedicated to “negro diseases,” in which naming a disease could be the road to prestige and higher fees for a physician. The Virginia-born Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright described at a professional conference a medical condition he had discovered called drapetomania, in a paper reprinted in DeBow’s Review in 1851. Drapetomania’s victims were “Negroes,” and its chief symptom was an irresistible urge to run away. When milder therapy failed, Dr. Cartwright prescribed “whipping the devil out of them.” He also described another purported disease, dysæsthesia æthiopica, or “hebetude of mind,” whose symptom was commonly described by overseers as “rascality,” and which was “much more prevalent among free negroes living in clusters by themselves, than among slaves on our plantations, and attacks only such slaves as live like free negroes in regard to diet, drinks, exercise, etc.”26 Dr. Cartwright was serious; the Southern medical profession had taken up the call to demonstrate the purportedly separate and inferior physical and mental characteristics of what was considered to be the “Negro race.”

Slaveowners had the power of life and death, and despite slaves’ monetary value as human property, death came to some from “punishments”—torture—and other violence inflicted by the owner or his agents, as Fannie Berry recalled in Petersburg, Virginia: “sometimes if [you rebelled], de overseer would kill yo’.”27 Others committed suicide.

It was much preferable to be enslaved in town. The urban enslaved generally enjoyed better material conditions than those on the plantation, as well as more independence of movement and association, more chances to make money, and, especially in port towns, a better chance to escape to free territory. Most of the work in Southern towns was done by “hired” slaves; the urban South developed in direct proportion to the amount of slave-rental that went on. Such Southern industrial work as there existed was mostly done by the enslaved, who sometimes managed to collect a bit of incentive pay.

Robert S. Starobin estimates that there were between 160,000 and 200,000 industrially employed slaves by the 1850s, 80 percent of them owned by the businesses’ owners and the rest rented.28 Ironworking was heavily dependent on enslaved labor. Slaves mined lead, salt, and coal. Turpentine production, a large industry, was almost entirely done by enslaved laborers. They manufactured rope, tanned leather, baked bread, cut lumber out of the Dismal Swamp till all the trees were gone, and operated gristmills and printing presses. In shipyards and textile mills, they worked side by side with poor whites in a sometimes violently uneasy coexistence that worked to the disadvantage of the enslaved.29

Enslaved workers cleaned and repaired Southern streets, laid down turnpikes, and dredged canals. They marked twain, shoveled coal, and sometimes were scalded to death or blown up in boiler explosions on the riverboats, with the more dangerous jobs going to older, less salable men. They built almost all the railroads in the South, as a March 30, 1852, advertisement in the Southern Recorder of Milledgeville, Georgia, illustrates:

IMPORTANT SALE OF NEGROES, MULES, &C. ON THE 27TH DAY OF APRIL NEXT.

The undersigned having nearly completed their contract on the South Carolina Railroad, will positively sell, without reserve, on TUESDAY, the 27th day of April next, at Aiken, South Carolina to the highest bidder –

| 130 | NEGROES |

| 85 | MULES, |

| 3 | HORSES, |

| 90 | CARTS and HARNESS, |

| 25 | WHEELBARROWS |

| 190 | SHOVELS, |

Railroad PLOWS, PICKS, Blacksmith’s, Carpenter’s and Wheel-right’s Tools, &c.

These Negroes are beyond doubt the likeliest gang, for their number, ever offered in any market, consisting almost entirely of young fellows from the age of twenty-one to thirty years, some few boys, from twelve to sixteen years of age, and four women.

Among the fellows are first rate Blacksmiths, Carpenters, Coopers, Brick-moulders, Wheel-rights and Wagoners.

Among the women, one excellent Weaver and Seamstress, another one, a good Cook. All well trained and disciplined for Rail and Plank-road working….

Terms Cash. J.C.SPROULL & CO., Aiken, S.C., immediately on the Railroad, 16 miles from Hamburg.30

In the towns and cities no less than on the plantations, virtually all domestic servants were enslaved; a white Southern woman who hired out as a maid had fallen on hard times indeed. In some cities, notably New Orleans and Charleston, enslaved women were major vendors of foodstuffs, whose customers were typically enslaved domestics doing the mistress’s shopping.

Slaves learned the hard way to anticipate the master and mistress’s slightest wishes. Having their ears boxed would be the least of it; they could be exposed naked to be brutally whipped with a knotted cowhide, leaving their backs and buttocks bloody raw. Slave narratives commonly contain accounts of severe punishment resulting in horrible scarring, maiming, or even death, for minor or even imagined infractions, for domestics no less than for field hands. A single example, selected almost at random from the literature, is J. D. Green’s testimony: “When I was fourteen years old my master gave me a flogging, the marks of which will go with me to my grave, and this was for a crime of which I was completely innocent.”31

Whether the victims were female or male, the torture of the enslaved also had a sexual component. There is little or no documentation of male-on-male intercourse, something unspeakable in that era, but there is much testimony about slaves being stripped naked and flogged, which today we would call sexual abuse. There are many stories of deliberate sadism in the slave narratives. After Henry Watson was trafficked to Natchez, he was sold to a man who beat him daily:

The first morning I was severely flogged for not placing his clothes in the proper position on the chair. The second morning I received another severe flogging for not giving his boots as good a polish as he thought they had been accustomed to. Thus he went on in cruelty, and met every new effort of mine to please him with fresh blows from his cowhide, which he kept hung up in his room for that purpose.32

Isaac Mason recalled that

whenever I did anything that was considered wrong … I had to go to the cellar, where I was stripped naked, my hands tied to a beam over head, and my feet to a post, and then I was whipped by master till the blood ran down to my heels. This he continued to do every week, for my mistress would always find something to complain of, and he had to be the servant of her will and passion for human blood. At last he became disgusted with himself and ceased the cruel treatment. I heard him tell her one day—after he had got through inflicting the corporal punishment—that he would not do it any more to gratify her.33

The enormous rawhide bullwhips were designed to lacerate; accounts mention whips cutting flesh to bone. Solomon Northup used the word “flaying.”34 “Many a time I’ve heard the bull-whips a-flying,” recalled Lizzie Barnett, a centenarian interviewed in the 1930s, “and heard the awful cries of the slaves. The flesh would be cut in great gaps and the maggots would get in them and they would squirm in misery.”35 These beatings—and other tortures too numerous to mention—could, and occasionally did, kill.

The enslaved had no right to refuse intimate services to the people who could order them beaten. Harriet Jacobs writes of her great-aunt Nancy, who “slept on the floor in the entry, near [the mistress’s] chamber door, that she might be within call” through six of Nancy’s pregnancies, all resulting in premature births.36

Sometimes enslaved concubines got special treatment, but sometimes not. Henry Watson’s owner had taken an enslaved woman “to wife” and had two children by her; she was “out in the field all the day, and in his room at night.”37 James Green recalled that “de nigger husbands weren’t the only ones dat keeps up havin’ chillen. De mosters and the drivers takes all de nigger girls day want. One slave had four chillen right after the other with a white moster. Their chillen was brown, but one of ’em was white as you is. But dey was all slaves just de same, and de niggers dat had chillen with de white men didn’t get treated no better.”38

The brutality of forced concubinage took place within the more fundamental brutality of being property: even the nicest master might be forced to pay his debts by selling his favorite slave, along with his children by her.

It mattered not whether white women disliked this state of affairs, since they had little or no legal standing themselves. The South Carolina plantation mistress Mary Boykin Chesnutt, author of a widely read diary and a good friend of Confederate First Lady Varina Davis, wrote angrily in 1861,

[O]urs is a monstrous system and [full of] wrong and iniquity … Like the patriarchs of old our men live all in one house with their wives & their concubines, & the Mulattoes one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children—& every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in every body’s household, but those in her own, she seems to think drop from the clouds or pretends so to think.39

Harriet Jacobs said it even more bluntly:

Southern women often marry a man knowing that he is the father of many little slaves. They do not trouble themselves about it. They regard such children as property, as marketable as the pigs on the plantation; and it is seldom that they do not make them aware of this by passing them into the slave-trader’s hands as soon as possible, and thus getting them out of their sight. I am glad to say there are some honorable exceptions.40

There is much testimony like that of Savilla Burrell, interviewed at the age of eighty-three in Winnsboro, South Carolina, who recalled (as transcribed) that “Old Marse wus de daddy of some mulatto chillun. De ’lations wid de mothers of dese chillun is what give so much grief to Mistress. De neighbors would talk ’bout it and he would sell all dem chillun away from dey mothers to a trader. My Mistress would cry ’bout dat.”41

Enslaved women were used for milk extraction, in the common case of wet nurses, or “sucklers”—women whose own babies had died or were pushed aside. Isabella Van Wagenen, better known as Sojourner Truth, born enslaved in New York in 1797, was said to have exposed her breasts to a proslavery crowd in Indiana that had questioned her gender while shouting that “her breasts had suckled many a white babe, to the exclusion of her own offspring.”42 Since enslaved women were pregnant so often, there was little need for a slaveowning white woman to feed her own baby, with the result that baby cotton planters grew up sucking from black women’s breasts. Nursing women might be lent out to a family member, or rented out to a stranger. In the latter case, the slaveowner was selling the protein and calcium out of the woman’s body.

While a “prime field hand”—young, healthy, strong, and male—was the benchmark of the slave market, the premium-priced captives were young female sex slaves, or “fancy girls,” who were light skinned or even passable as white. A teenaged “fancy girl” purchasable either for private sexual use or pressed into commercial service by a pimp could bring a multiple of what even a “prime field hand” might command.

A number of reports from the later days of slavery mention blond-haired, blue-eyed slaves on sale—the children of enslaved women, despite their phenotype. Fredrika Bremer, the Swedish novelist who visited Richmond in 1851 as part of an extended journey, wrote in her widely read Homes of the New World of visiting “some of the negro jails, that is, those places of imprisonment in which negroes are in part punished, and in part confined for sale.” She visited one “where were kept the so-called ‘fancy girls,’ for fancy purchasers,” and yet another where “we saw a pretty little white boy of about seven years of age, sitting among some tall negro-girls. The child had light hair, the most lovely light-brown eyes, and cheeks as red as roses; he was nevertheless the child of a slave mother, and was to be sold as a slave. His price was three hundred and fifty dollars.”43

The enslaved caste grew with every generation. Escape, whether by flight or by manumission, was difficult to achieve; the census counted 1,011 escaped slaves in 1850, “about 1/30 of one percent” of the enslaved.44 People in the Chesapeake might escape to free territory in the North, but in the Deep South, that was practically impossible. The lighter-skinned an enslaved person was, the greater the possibility that he or she might be able to steal away, escape the dragnet that routinely captured unaccompanied black people, and pass for white under a new identity; Thomas Jefferson allowed two of his four children by Sally Hemings to do so, under which cover they disappeared from the historical record.

Notwithstanding the severity of the whippings that occupy such a prominent role in slave narratives, the threat of sale was the most powerful coercive weapon in the slavemaster’s arsenal. As Isaiah Butler of Hampton County, South Carolina, put it: “Dey didn’t have a jail in dem times. Dey’d whip ’em, and dey’d sell ’em. Every slave know what ‘I’ll put you in my pocket, sir!’ mean.”45 No aspect of slavery was more emblematic of its horror than forced separation of families, which took place regularly and publicly in the theater of the slave auction.

Slave marriages were not binding on the slaveowner, and forced mating was always possible, sanctioned by law and by custom. Even those whose families remained together knew that the fortunes of a slave could change in a heartbeat. The enslaved lived with the knowledge that they or a loved one—a mate, a sibling, a child—might at any moment be removed without warning from their familiar world and taken away from their family without so much as a fare-thee-well.

The slave trade routinely destroyed marital relationships, along with all other family ties, by selling one or the other partner away. Robert H. Gudmestad estimates that “forced separation … destroyed approximately one-third of all slave marriages in the Upper South.”46 Marriage between slaves was sometimes solemnized and celebrated on the plantation (“jumping the broomstick”), but it was a charade: there was no such thing as legal marriage for slaves. As Matthew Jarrett, born in 1848 and interviewed in Petersburg, Virginia, put it, “don’t mean nothin’ lessen you say ‘What God done jined, cain’t no man pull asunder.’ But dey never would say dat. Jus’ say, “Now you married.”47

An individual slaveowner might respect slave marriages, but when he died, the heirs would have to divide up the estate at auction.

Masters often tried not to let slaves know in advance they were going to be sold, since they tended to run away if they knew. They ran away in any case, everywhere there was slavery. Among the many fragmentary song lyrics collected as part of the Federal Writers’ Project oral histories, none appears more frequently than Run, nigger, run / Patter-roller* catch you, a song sung by both white and black in the South. The surveillance society was a reality to African Americans in slavery—not that people didn’t run away anyway. Maroons often hid out in their home region, sometimes hiding for years in underground dugouts or hard-to-access places, sometimes returning to the plantation surreptitiously at night for food and on occasion returning to the workforce after negotiating conditions for their return.

Men ran away more than women, who might be gang-raped if caught, as described by the fugitive Lewis Clarke in 1842: “They know they must submit to their masters; besides, their masters, maybe, dress ’em up, and make ’em little presents, and give ’em more privileges, while the whim lasts; but that ain’t like having a parcel of low, dirty, swearing, drunk, patter-rollers let loose among ’em, like so many hogs.”48

Masters grew up with “little shadows,” personal child servants who did everything for them, were not allowed to fight back when they were abused, and were in deep trouble if anything happened to their young master. The three-quarters white William Wells Brown was an enslaved “playmate” at the age of nine for a five-year-old master to whom he was related. The position carried the privilege of wearing a white linen suit; he had to audition for it against “some fifteen” others by doing gymnastics. After the family moved to Missouri, Brown recalled that

William had become impudent, petulant, peevish, and cruel. Sitting at the tea table, he would often desire to make his entire meal out of the sweetmeats, the sugarbowl, or the cake; and when mistress would not allow him to have them, he, in a fit of anger, would throw any thing within his reach at me; spoons, knives, forks, and dishes would be hurled at my head, accompanied with language such as would astonish any one not well versed in the injurious effects of slavery upon the rising generation.49

When masters became older, they sometimes bet and lost their childhood companions to strangers in card games, or they might be sold to pay an extraordinary expense. In Roswell, Georgia, a town founded by Pierce Butler’s former manager Roswell King as a summer refuge for the wealthy, James Stephens Bulloch sold off four enslaved people to pay for his younger daughter Mittie’s grand wedding at Bulloch Hall on December 22, 1853.50 Bulloch did not sell Mittie’s personal slave, whose too-appropriate name was Toy. Nor could the “shadow” of Mittie’s troubled half brother Daniel Stuart Elliott be sold, because Daniel had previously shot and killed him in a fit of temper.51 But Bess, the attendant of Bulloch’s older daughter Anna, was sold together with her son John for $800. Anna, who had no husband and was therefore of no economic importance, subsequently became governess to Mittie’s children, one of whom was the future president Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

“When your marster had a baby born in his family,” recalled an unnamed formerly enslaved woman in Tennessee, “they would call all the niggers and tell them to come in and ‘see yur new marster.’ We had to call them babies ‘Mr.’ and ‘Miss’ too.”52 If a little white boy with a Roman-numeraled name said up was down, his captive black playmate had better agree. Once the boy was grown into a planter, if he said up was down, who dared correct a man who was accustomed to punishing disagreement with torture? Virtually all of the members of the Southern aristocracy that seceded from the United States grew up with such a regime, going back ten generations for the oldest families among them.

Up became more down with every passing decade, and more incompatible with the outside world. The build out of the slavery ideology became more elaborate, more radical, and more delusional as each generation began from a more doctrinally inbred point of departure. Meanwhile, it became more belligerent, accompanied by a vigilant suppression of dissent.

Antislavery opinions were not to be expressed publicly in the slave states. That was considered traitorous and was repressed with violence that was sometimes spontaneous and sometimes organized. Any perceived slight to the system of slavery could provoke a hair-trigger response. There was not even a pretense of free speech on the subject of slavery in the South, nor did slavery’s defenders want anyone in the North to criticize, or even mention, slavery. The enslaved were, needless to say, not to speak against their captivity. They were to be happy, or else. They loved their master, or else.

Unlike Africans—or, more horrifying to slaveowners, the “French Negroes” of Haiti—African Americans were believed to be docile, since scrupulous attention was paid to keeping them ignorant of military technique. That was one of the attractions of “Virginia and Maryland Negroes” in the market—they had been raised to an unquestioning submission to the work regime, or so it was believed.

That belief was disproved daily. For all their powerlessness and the almost unimaginable degree of their exploitation, the enslaved were social actors—of course they were—who, despite their great disadvantages, had some ability to negotiate their conditions. They also had the dangerous power that stemmed from slaveholders’ fear of them.

Rebellions existed wherever there was slavery, in every era, because everywhere, always, the enslaved were at war with their condition. Rebellions happened on the slave ships, on the plantations, and in the towns. Herbert Aptheker, writing in 1943, found “records of approximately two hundred and fifty revolts and conspiracies in the history of American Negro slavery,” defining such incidents as involving ten slaves or more and with the intention of obtaining freedom.53

Smaller rebellions were ubiquitous. Every runaway was a rebel, and there were runaways at almost every plantation. Often escape attempts were unsuccessful and violently repressed, while others were temporary with a negotiated end, and some were successful and permanent. Twenty-two-year-old Ona Judge, who was Martha Washington’s personal servant, escaped from the President and First Lady of the United States in Philadelphia in 1796 after learning she was to be given away as a wedding gift. She married a free black man in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and managed to avoid falling prey to the attempts at recapture that George Washington attempted against her until he died in 1799.54

Every slave who got into a suicidal, or perhaps murderous, fight with an intolerable overseer was a rebel. Every slave who took something from the master (called “stealing,” as if the master were not the one stealing from his captives) was a rebel. Every enslaved person who learned to read was a danger. The now-common term “day-to-day resistance,” proposed by Raymond A. and Alice H. Bauer in 1942, expresses the ongoing inconformity of the enslaved with their status.55

The larger rebellions, small though they were in military terms, were extraordinarily effective at bringing the war on slavery forward: the Stono rebellion (1739), the alleged New York conspiracy (1741), Gabriel’s conspiracy (1800), the German Coast rebellion (1811), Denmark Vesey’s alleged conspiracy (1822), Nat Turner’s rebellion (1831), and others were sensational news when they happened. To slaveowners, they were a portent of apocalypse.

Major foreign wars were also occasions of slave rebellion, though it was folded into the larger context. Collectively the enslaved formed a Fifth Column in every war, siding with those who promised to deliver them from the death-in-life of slavery. In Saint-Domingue, black generals fought with the Spanish against the French, with Toussaint Louverture crossing over to the French once France had declared emancipation in North America. The enslaved of Virginia and points south defected to the British during the War of Independence and again during the War of 1812. Then in 1860 they supported the Union against the Confederacy, first as “contrabands” who decamped en masse, and then as soldiers. After they were allowed to fight against the Confederacy pursuant to the Emancipation Proclamation, the war was won.

Abolitionist books and publications by David Walker, Benjamin Lundy, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and others cast a long shadow. In the eyes of slaveowners, they were multiplied manyfold into a giant “San Domingo,” with the aid of demonized figures like John Quincy Adams, William Seward, Salmon P. Chase, and Charles Sumner. This was the much-decried “Northern aggression,” whose forces were, in the minds of the South’s political class, gathering to swoop down on the defenseless South, when purportedly savage “Negroes,” would, it was believed, be let loose to rape, pillage, and kill, with nothing less than the destruction by murder and amalgamation of the white race as their object.

A letter to a Fredericksburg, Virginia, paper in 1800 declared that “if we will keep a ferocious monster in our country, we must keep him in chains.”56 In other words, the omnipresent, entirely legal violence of slavery was an ongoing state of war.

*patteroller = patroller