6

6 6

6Slavery was not the beautiful state of love and confidence between masters and slaves that we often see pictured in books.1

SLAVERY WAS THE CENTRAL fact of Southern life.

Slaveowners formed the whole of the Southern political class and controlled Southern governments from top to bottom, with South Carolina the most proudly antidemocratic of all. The pro-slavery plutocracy of 1860—the Slave Power, abolitionists not incorrectly called it—had the full weight of American legal history behind it in claiming as its property 38.9 percent of the people of the slaveholding states (57 percent in South Carolina).

The legal systems of the Southern states were organized around maximizing slaveholder profit. In the towns, repressing the enslaved population was the principal goal of the policing system, which was not one of beat cops on patrol but of military-style squads that made street sweeps. In Charleston, these sweeps were done nightly by twenty to thirty officers at a time, which required much higher levels of manpower than Northern police forces.2

With their enslaved assets fully capitalized, slaveowners were not merely wealthy; they were spectacularly wealthy. At the time of secession, two-thirds of the millionaires in the country lived in the slave states, with most of their wealth in the form of slaves.3 The Slave Power became wealthier with every territorial annexation for slavery: new territories meant new slave markets, which jacked up the resale value of existing slaveholdings.4

Protecting and developing enslaved assets—most definitely including reproductive value—was slaveowners’ first, second, and third political order of business. With the leisure provided by living on the proceeds of slave labor and in the absence of other profitable ventures in the largely nonindustrial South, they had plenty of time to pursue politics, in which they competed to be the most faithful to the ideal of slavery and its concomitant philosophy of states’ rights.* Thanks to the compromises brokered at the Constitutional Convention and to the slaveowners’ bloc-voting fraternity, they exercised disproportionate political power at the national level, right up through the collapse of their system.

Slaveowners were an elite within their own geographically and ideologically isolated societies, with those who owned the most slaves at the apex of the social and political order. According to the detailed US census of 1860, which enumerated slaves and slaveholders in its “Agriculture” supplement, the 347,525 owners of one or more slaves constituted only 4.3 percent of the 8,039,000 “whites” in the fifteen slaveholding states (eleven of which would shortly secede) and 2.86 percent of the population of those states as a whole. If, as Frederic Bancroft did, we count the population of slaveholding families as five times the number of slaveowners, some 14 percent of the population of the slave states were of the slaveholding class. Perhaps one-half of 1 percent of the population of the slaveholding states owned a hundred slaves or more, and a few owned a thousand or more. It has been suggested that the 1860 census numbers might have underreported large slaveowners, but it’s unlikely that large slaveholders—again, almost the entire political class of the South—amounted to even 1 percent of the population of their states.

The South’s 1860 population of 3,953,742 enslaved people comprised or made viable an estimated four billion dollars’ worth of private property, as per Mississippi’s declaration of secession: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery…. We must either submit to degradation and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union.”6

This figure, which turns up in other contemporary writings, was an estimate of the South’s capitalization. It apparently valued slaves at a blunt average of $1,000 per human being, or maybe something like $800 per human being and $200 for the land he or she worked on. Slaves were not all the property involved in that quick-and-dirty computation, but they were most of it, the rest being land and equipment that Southerners insisted would be valueless without slave labor. Some estimates said three billion dollars, and some said two billion; sporadic sales reports in Southern newspapers during the final years before the war, at the dizziest peak of the market, suggest that a thousand a head for a total of four billion dollars might not have been too high a figure to put on it. At the beginning of 1860, the Albany (GA) Patriot reported an estate liquidation of 536 people—one of the largest slave sales ever—that brought an average price of $1,025 per person sold, making the total sale worth more than $15 million in 2014 dollars. Another estate sale from Columbus brought an average of $1,084. The Mobile Daily Advertiser of January 18, 1860, reported a Mississippi sale with an average price of $1,145.7

Four billion dollars in 1860 was equivalent to about a hundred billion in 2010. It was more than 20 times the value of the entire cotton crop that year and 17.5 times all the gold and silver money in circulation in the United States ($228.3 million, most of it in the North). It was more than nine times the $435.4 million of currency in circulation—which, pursuant to the dismantling of the national banking system by President Andrew Jackson, was issued by local banks whose notes depreciated over distance.

Four billion dollars was more than double the $1.92 billion value of farmland in the eleven states that seceded.* Without labor Southern land lost what value it had, but even with labor Southern land in 1860 still was worth much less than land in the free states. In the census of that year, farmland in the mid-Atlantic states was valued at $28.08 an acre, and in New England at $20.27 an acre, but in the Southern states it was only worth $5.34—even though the South was producing the big export crops.8 Farms in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and Illinois were more improved, more diversified, better tended, more mechanized, better connected to market by infrastructure, and were worked by family or wage labor instead of by capital-intensive slaveholdings.

It was almost a laboratory experiment: two mutually exclusive economic systems competing for territorial expansion and financial supremacy, each one having at the start about the same number of inhabitants—but one allowing enslaved human property and the other not. Slave societies were caught in a downward spiral. Slavery brooked no competition from free labor, and without a broad consuming class of wage laborers, the slavery bloc furnished no domestic market for the products of industry. Moreover, industrial working conditions involving complicated machinery proved a more problematic situation than field labor for workforce discipline, which often had to be resolved with some kind of incentive pay for the enslaved, something the politics of plantation slavery was resolutely opposed to. Without industry, the South slid further and further behind while the North modernized and grew in population.

Meanwhile, the South had no foreign outlet for its other main product besides cotton: slaves. With slaveowners’ encouragement, and sometimes their participation, the enslaved population was increasing by 25 percent or more every decade, even in the face of high mortality among the generally unhealthy enslaved.

With domestic labor needs being met, the South looked to territorial expansion for the growth of its slavery business. By 1860 North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri—and even Alabama and Mississippi—were no longer importing enslaved laborers from their neighbors to the north but were exporting coffles as far west as they could go. As more states became slave sellers, having new territories to sell slaves into became a matter of ever greater urgency.

From President Jefferson’s time forward, the grand prize of territorial expansion was Cuba. In his first year of retirement from political office, ex-president Jefferson rhapsodized in a letter to his protégé, President James Madison, about his imperial dream that the United States would acquire Cuba with Napoleon Bonaparte’s blessing, and would conquer Canada in war: “We should have such an empire for liberty as she has never surveyed since the creation: & I am persuaded no constitution was ever before so well calculated as ours for extensive empire & self government.”9 Then he described the weather and the condition of his gardens, and thanked Madison for the squashes he had sent.

When a “founding father’s” remarks about “liberty” don’t seem to make sense, substitute the word “property” and they do. Taking over Havana would have created an empire of liberty, all right—for slaveowners. Jefferson wasn’t fantasizing about freeing the two hundred thousand or so slaves who were being systematically worked to death on Cuba’s sugar plantations and replaced by new arrivals from Africa. Cuba was at that time a fantastically productive sugar machine that was still in the early phase of its multi-decade peak of importation of kidnapped Africans. Acquiring Cuba would have been a windfall for Virginia slave breeders and would have added two reliably pro-slavery senators.

In 1861, slaveowners went to war with the North over slavery, as South Carolina’s planter class had been inciting them to do for decades. The idea that the South fought a war so that it could be left in peace to have slavery merely within its settled boundaries is sometimes voiced as a cherished myth today, but it does not fit the facts on the ground, nor did anyone think so at the time. Quite the contrary: the war was fought over the expansion of slavery. Southern rulers feared being restricted to the boundaries they then occupied. The dysfunctional-from-the-beginning Confederate States of America was set to have an aggressively annexationist foreign policy.

Premised on infinite reproduction into an ever-expanding market, the slave-breeding economy was like a chain letter or a Ponzi scheme: sooner or later someone would be left holding the bag. Expansion into other territories was thus presented as a demographic imperative; in the last days of 1860, two Alabama “secession commissioners” sent to pitch secession to the North Carolina legislature announced that:

[Alabama’s black] population outstrips any race on the globe in the rate of its increase, and if the slaves now in Alabama are now to be restricted within the present limits, doubling as they do once in less than thirty years, the [white] children are now born who will be compelled to flee from the land of their birth, and from the slaves their parents have toiled to acquire as an inheritance for them, or to submit to the degradation of being reduced to an equality with them, and all its attendant horrors.10

Though the Jeffersonian “empire for liberty”—which, like we said, meant slavery—never managed to annex Cuba, it confiscated vast amounts of Native American territory as it pushed into western Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, and, after an international war of territorial conquest, Texas. Slaveowners fought bitterly but unsuccessfully to have slavery in New Mexico, California, and, in an 1854 armed confrontation of national dimensions, Kansas and Nebraska. Until Lincoln, they were used to having the president on their side.

The clash between slave labor and free-soil—the “irrepressible conflict,” to use William Seward’s phrase of 1858—resulted in the overthrow of slavery. But it was not merely a clash between labor systems; it was a clash between monetary systems.

When slavery was abolished and the on-paper value of flesh-and-blood capital disappeared from the balance sheet, the wealth of the South evaporated. Since the South’s economy had been built entirely on a foundation of slavery, there was nothing to substitute for it. There were as many laborers as before, but they could no longer be coerced. There was nothing to pay labor with, because the labor had been the money. The security for hundreds of millions of dollars in debt walked away, leaving the obligations valueless, the credit structure imploded, the hundred-dollar Confederate notes trampled in the mud, and the planters owning worthless land.11

Emancipation destroyed an entirely legal form of property, which is why it was a revolution.

Before achieving independence, the thirteen quarrelsome colonies were already well along with the process of cleaving into two interdependent but hostile economies. As each new territory came into the Anglo-American system, its policies regarding slavery and slave trading occasioned a shifting of the balance of power in the economy. The tension was there all along, and it formed arguably the greatest obstacle to union at the Constitutional Convention. The difference was not merely one of large states versus small states, or protective tariffs versus free trade, or even wage labor versus enslaved labor; it went directly to the issue of property rights in people. Within that framework, however, there was a sharp competition between the two major centers of power in the slave societies: Virginia and South Carolina. The commercial and political antagonism between the two went back to colonial days.

We’re going to turn back to the sixteenth century now, in order to describe the formation of the states of the Chesapeake and the Lowcountry, each in their differing social and political particulars. We begin just before the establishment of an English colony in North America, when the first known group of enslaved Africans brought to live in the present-day territory of the United States rebelled and escaped.

*“States’ rights” was not implicitly a slaveholders’ project at first; Massachusetts nearly seceded during the War of 1812. But a states’ rights slaveholders’ doctrine can be traced from Patrick Henry to John Randolph to John C. Calhoun, who more than anyone made it the boilerplate of slavery.5

*Notwithstanding the thirteen stars on the Confederate battle flag, there were only eleven Confederate states (in order of secession: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee). The other two stars represented Kentucky and Missouri, slave states that did not secede, though a Confederate government proclaimed itself in Missouri in addition to the Union government.

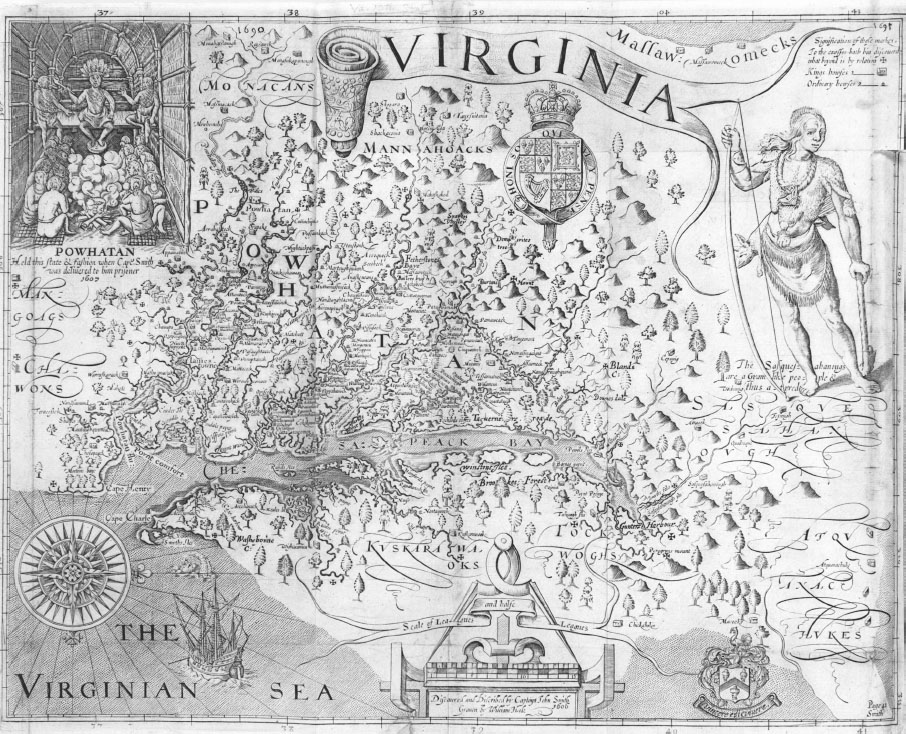

John Smith’s map of Virginia, showing the “Virginian Sea,” dated 1606 on the legend. North is to the right; the four major rivers on the western shore of the Chesapeake can be seen clearly.