7

7 7

7It will rather hasten ye Spaniards rage, then retard yt; because he will see it, to grow every day harder for him to defeat us.1

Those who are now boastfully called popes, bishops, and lords [have issued from] such a pompous display of power and such a terrible tyranny that no earthly government can be compared to it … we have become the slaves of the vilest men on earth.2

TODAY THE LAND AROUND Sapelo Sound is part of Georgia, but in 1526 the Spanish considered it part of the vaguely bounded territory Juan Ponce de León had named in 1513: Florida.

It was probably somewhere near Sapelo Sound that the conquistador Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón established a Spanish colony in 1526, bringing some six hundred people from Santo Domingo in six vessels—including an unknown number of enslaved Africans, whose precise point of origin is also unknown, along with eighty or perhaps a hundred horses.

It was a mighty undertaking, the first since Ponce de León had left the region, and Ayllón carried a commission from Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain Carlos V. Unfortunately, Ayllón’s short-lived town of San Miguel de Guadalpe became that archetypal horror of colonial history: a failed settlement in the wilderness. Ayllón died of disease; the Africans rebelled, burning down the colonial prison; and one hundred fifty or so surviving Spanish colonists made their way back to the island of La Española (or Hispaniola).

The Africans appear to have been left behind to live or die among the Guale Indians, beginning Florida’s tradition of marronage, a state of outlaw freedom for a self-emancipated slave.* Their ultimate fate is unknown.3

In his explorations, Ayllón had discovered the major watercourses of North America’s east coast, including the Chesapeake Bay, which first appears on a map with the name Bahía de Santa María. After various failed ventures, including a brief reign of slaughter and enslavement of Native Americans under Hernando de Soto in 1539, Spain gave up trying to colonize Florida. But the Spanish king’s hand was forced by the appearance of a colony of heretics.

Martin Luther’s revolution (October 31, 1517) never took hold in militantly Catholic Spain. But in northern Europe, where dissident mobs attacked churches and monasteries, destroying statues and images in iconoclastic riots, what came to be called Protestantism was an active political project. It was a new kind of movement, disseminated by the booming technology of moveable-type printing, which thrived in northern Europe on Bible sales, creating as it did so a new political medium—the printed tract—that gloried in a rhetoric of freedom versus slavery that would carry forward into the coming centuries.

African slavery, introduced into Iberia by Portugal in 1441 or so, had not yet developed on a large scale in the Americas, nor did it exist in most of Europe, where slavery was associated with Spain and Portugal—as were black people, who in England were called blackamoors, reflecting their Iberian provenance. But though Martin Luther had no personal contact with slavery, he used the term frequently, describing conditions of the soul and of the church in terms of liberty versus slavery. In his theology, freedom was associated with reading the Bible in one’s own language, and slavery was associated with Catholic ritual.

As Europe divided into Catholic and Protestant camps, a series of civil wars paralyzed France for four decades. Huguenots, followers of Jean Calvin who numbered at their peak a little more than a tenth of the French population, were mostly urban people, many of them tradesmen, at odds with a mostly rural, agricultural country. When they declared their church an established institution with a national synod in 1559, a crisis began.4

Then, the following year, a ten-year-old was crowned king of France—Charles IX, whose affairs were guided by his Italian mother, Catherine de Medici, acting as regent. Catherine saw the growth of Protestantism as a threat to the state, and allied the French throne with Spain against it, while the Huguenots sought English and German support.

On February 18, 1562, the Huguenot sea captain Jean Ribaut embarked on a French colonizing mission across the Atlantic, which meant creeping into territory claimed by Spain. Flying the banner of his Catholic child-king, he founded the settlement of Charlesfort, at present-day Parris Island, in what later came to be called South Carolina.

Ribaut found the indigenous people* to be friendly, and when one of them showed the French the best place to land their vessel, Ribaut had him “rewarded with some looking glases and other prety thinges of smale value”—the beginning of a long cycle of trade between Native Americans and Europeans in the area.5 As the richness of the unplowed land became apparent, and after Ribaut presented more gifts, he asked the question most on Europeans’ minds:

we demaunded of them for a certen towne called Sevola [Cibola], wherof some have written not to be farr from thence…. Those that have written of this kingdom and towne of Sevolla … say that ther is great abound-aunce of gould and silver, precious stons and other great riches, and that the people hedd ther arrowes, instedd of iron, with poynted turqueses.6

Ribaut kidnapped two of the natives but, to his apparent surprise, they did not want to be captives, and they escaped: “We carried two goodly and strong abourd our shippes, clothing and using [treating] them as gentlly and lovingly as yt was possible; but they never ceassed day nor nyght to lament and at length they scaped away.”7

Leaving twenty-eight men behind at Charlesfort, Ribaut returned home to raise money, but he found France’s ports closed. Two weeks after he had embarked from France, the Duc de Guise had massacred a group of Huguenots at worship, and in Ribaut’s absence, a religious civil war had begun. He went instead to London, a city he knew well and whose language he spoke, where in May 1563 he published a forty-four-page pamphlet whose short title is The whole and true discouery of Terra Florida. In it, he noted that the natives would trade for “littell beades of glasse, which they love and esteme above gould and pearles for to hang them at there eares and necke.”8

The pamphlet brought Ribaut to a meeting with England’s Queen Elizabeth, who wanted to mount an English expedition to Florida. She briefly gave Ribaut “a salary of three hundred ducats and a house,” as the Spanish ambassador duly reported to the Hapsburg monarch Felipe (Philip) II, but then she had him imprisoned in the Tower of London after he tried to escape with four French hostages Elizabeth was holding.9

By then, the desperate, quarreling men Ribaut had left behind at Charlesfort had resolved to sail home. Running out of food and water on the voyage, they drank their own urine and turned to cannibalism, killing and eating an unfortunate outcast of their number before they were picked up by a British ship.10

A second, much larger, colonizing voyage from France brought both women and men to Florida when René Goulaine de Laudonnière, Ribaut’s former second-in-command, established the Huguenot colony of Fort Caroline (also named for Charles IX) on June 22, 1564, near the site of present-day Jacksonville, Florida. Laudonnière brought an official expedition painter along, who depicted the sixteenth-century aristocrat dressed in “a crimson, yellow, and blue costume,” in yellow boots with red linings, and three colors of plumes in his hat.11 His colonists recorded eight births during the short life of their community.12 Unfortunately, they neglected to plant sufficient crops in the fall, so when famine struck they took an Indian chief hostage for a food ransom.13

Even more unfortunately, they were in the high-security Gulf Stream corridor.

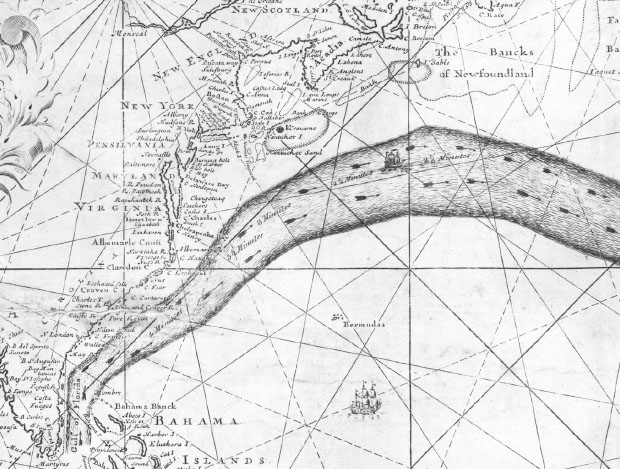

Ponce de León noted in his journal of 1513 that his three ships encountered a current they could not go against, despite favorable winds. He had discovered the strongest current in all the world’s oceans—a one-way express lane in the sea, where the water was warm even when the air was cold. More than two centuries later, Benjamin Franklin named it the “Gulf Stream.”

Driven in a west-to-east direction by the Earth’s rotation and intensified by the temperature differential between equatorial and polar latitudes, the Gulf Stream is stronger in the summer than in the winter. It originates after the waters of the Caribbean pass northward through the Straits of Yucatán, pouring into the Gulf of Mexico and making the clockwise circuit in the Gulf now known as the “loop current.” The current is amplified again, and the waters become more turbulent, when it shoots eastward through the constricted passage of the Straits of Florida. Following along the eastern coast of the United States, it reaches its closest point to land near present-day Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, before gradually veering away from the coastline and out into the Atlantic. There it divides into two main branches, with one continuing up the North Atlantic along the “great circle” route to Europe, while another branch curves off eastward, leading to Spain.

Detail of the 1768 Franklin-Folger map showing the Gulf Stream, which diverges from the mainland off the coast of North Carolina.

Every year, a Spanish fleet bound for Sevilla sailed up the Gulf Stream out of the port of Havana, packed full of silver and gold ripped out of the bowels of Mexico and Perú. The volume of silver sharply increased as of 1557, when the Spanish mines began using an amalgamation refining process that involved indigenous slaves tromping in a toxic slurry of mercury, a labor force that was soon to be augmented with Africans.

When the Spanish king Felipe II learned that French Protestants had established a colony on the mainland at a potential choke point for the route his treasure ships took, he commissioned the militantly Catholic Don Pedro Menéndez de Avilés as adelantado (governor) of Florida, instructing him to establish a Spanish presence on the North American mainland that would remove the interlopers.

William Hawkins made what was probably the first African trading voyage—but not a slave-trading one—from England in 1536, traveling from England to “Guinea” (Africa) and then to Brazil. The first English company to finance commercial ventures to Africa seems to have been a London syndicate founded in 1540, but there was little further action until a highly lucrative voyage brought back gold, ivory, and hot peppers in 1553. It was followed by more expeditions, and Queen Elizabeth became an African-venture partner in 1561. These voyages, which did not entail carrying off kidnapped people, created good relations with the African traders, but Hawkins’s son John changed that.14

There are two previous documented incidents of Englishmen engaging in commerce of small numbers of slaves, but John Hawkins was the first to make a profitable “triangular,” or clockwise, slave trade. Moreover, he not only traded in slaves but participated in raiding for them, burning a town on the Gold Coast during his first voyage. He also seized them from other slave traders through piracy—or rather, as a privateer.

Privateering—the state endorsement of commercial piracy against vessels of other flags in furtherance of military and political objectives—was an early form of capitalism as war. “The setting forth of a privateer required considerable capital,” writes Kenneth R. Andrews. “Even in ventures consisting of one small ship, the joint-stock system of investment was used more often than not.”15 In England, the partners were adventurers, a word implying joint-investor commercial enterprise, as in the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London, apparently already in existence when it was chartered by Henry VII in 1407. Freelance piracy by English captains flourished during Queen Mary’s reign (1551–58), but Queen Elizabeth, Mary’s half sister and successor, gave the former pirates letters of marque to become privateers and used them as a tool of policy—“a privileged criminal class,” in the words of Hugh F. Rankin.16

Investment in privateering ventures was facilitated by the improved quality of English money during Elizabeth’s long reign (1558–1603). Henry VIII had imposed what is remembered as the Great Debasement on his coinage as a money-making trick, sabotaging the value of the monarch’s money. But Elizabeth’s financial advisor Thomas Gresham accomplished the considerable feat of calling in the debased coinage and replacing it with newly minted gold sovereigns within a year (1560–61). Restoring value to the money created the conditions for a credit market to thrive, without which no long-distance trade could function. Gresham also impressed on Elizabeth the wisdom of raising money domestically from England’s own internal commerce instead of from foreign bankers as the Spanish crown did. From Elizabeth’s time forward, England was a financial center.

Backed by a syndicate of investors, Hawkins took three ships to Sierra Leone in 1562 with the intention of capturing Africans to sell in La Española and thereby to violate the Spanish trade monopoly. Once arrived on the African coastline, he plundered Portuguese traders and made a slave-raiding alliance with an unnamed African king. He had some three hundred captives to sell by the time he arrived at La Ysabela, Columbus’s now-vanished first settlement near present-day Puerto Plata in the Dominican Republic. Arriving with more soldiers than the Spanish had, he said he’d behave if he got to do business. After selling the Africans to eager customers, he acquired two more ships and loaded all five up with sugar, hides, ginger, and pearls for the return voyage to Europe, ultimately turning a profit for his investors.17

Hawkins’s second triangular voyage, heavily subscribed by merchant adventurers in 1564, brought back gold, silver, and pearls. On his return in August, he stopped at Fort Caroline in need of fresh water. There, in a gesture of Protestant solidarity against the Spanish, he saved the remaining Huguenot colonists by trading them food and a ship he didn’t need in exchange for a Spanish brass cannon they had captured. During the months Hawkins remained there, Jean Ribaut arrived; released from the Tower of London, he had brought a fresh colonizing expedition of five hundred men and two hundred women.

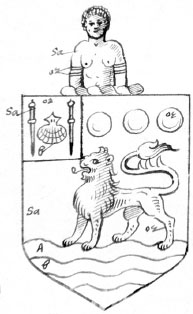

Design for Sir John Hawkins’s crest, depicting an African woman, bare-breasted and bound, 1568.

In Spain, Menéndez’s huge expedition to Florida was already in preparation when the news of Hawkins’s arrival at Fort Caroline arrived. To the Spanish king, it seemed proof of an international alliance to break his control of the Americas, and he ordered Menéndez to speed up his departure.

Menéndez had Felipe’s trust. He had fought against the forces of the French Valois king François I under Felipe’s father, Carlos V, and he had successfully escorted Felipe to London in 1554 for Felipe’s short-lived royal marriage to his Catholic second cousin, the English Queen Mary Tudor.*18 He was captain general of the Carrera de Las Indias, the transatlantic treasure route, during what is remembered as Spain’s Siglo de Oro, its Golden Age. With the security for Spain’s entire money supply and commerce on his shoulders, as well as a fantastically lucrative upside should his franchise thrive, he took his responsibilities to God, king, and silver seriously. At enormous personal expense, he brought to Florida an armada of ten ships carrying 995 people, 300 of whom were veteran soldiers, along with 200 horses. They landed on the day of San Agustín (August 28, 1565), founding the town that today is still called St. Augustine—the oldest continually occupied European-style city in the United States, though there are older Native American communities.

Shortly after Hawkins departed Fort Caroline, Menéndez captured it in a surprise attack.19 As the massacre began, he gave an order to spare women and children under fifteen (though some were apparently dispatched before the order to spare them was communicated).20 One hundred forty-three men were killed, according to one source, although Laudonnière escaped.21 Others were slaughtered in the countryside as they fled. The Spanish caught some two hundred of them, who had to be confirmed as members of the nueva religión before being executed, because they could escape death if they declared themselves Catholics. When they refused, they were taken behind a sand hill in groups of ten with their hands bound, and their throats were cut.

The Spanish found six cases of the Huguenots’ gilt-edged Bibles, which they burned. Ribaut got away with some 350 of his people, but their boat was shipwrecked near St. Augustine and Menéndez caught them. Gonzalo Solís de Merás, Menéndez’s official chronicler and brother-in-law, noted that Ribaut offered a ransom to spare their lives, but Menéndez spared only “the fifers, drummers, trumpeters, and four more who said that they were Catholics, in all sixteen persons: all the others had their throats cut,” including Ribaut.22 One town had exterminated another town thirty miles away. The site is still known today as Matanzas (Massacre) Inlet. It was a small massacre, however, compared to the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of August 1572, when the gates of Catholic Paris were closed and three days of killing of Huguenots began, followed by similar massacres in twelve other French cities that claimed an unknown number of thousands of victims.

With the Huguenots of Florida annihilated, the Spanish Fleet of the Indies continued its annual treasure runs from Havana through the Straits of Florida. To Christianize the natives, Menéndez established a mission system that was the first interconnected circuit of European settlements in North America. He established firm military control over the region, sending a detachment up north to build a fort where the Charlesfort community had been, calling it Santa Elena (St. Helena in English). One of his captains, Juan Pardo, built Fort San Juan in western North Carolina, near present-day Morganton, the ruins of which were unearthed by archaeologists in the first decade of the twenty-first century.23 The area north of St. Augustine would remain a zone of conflict between Protestant and Catholic states for almost two centuries more.

Hawkins made his third and final slave-trading voyage in 1567, taking between four and five hundred captives, but Spain mounted effective resistance, and his expedition lost money.24 The English did not immediately continue the slave trade, but John Hawkins had started them in it.

By this time, Spain had purchased tens of thousands of Africans from Portuguese slavers to work in its silver and gold mines in Mexico and Perú. It was becoming clear how vulnerable the Spanish American possessions were to slave rebellion, given how badly outnumbered the whites were, and how vulnerable they were to attack from free black people whose arrival in the hemisphere predated that of the English. With the help of numerous maroons, as well as Huguenot privateers, Hawkins’s nephew Francis Drake captured a fortune in gold—he had to leave the silver behind for lack of vessels to carry it—when he attacked one leg of the Spanish treasure fleet at Nombre de Dios, Panamá, in 1573.

England’s Queen Elizabeth knew well the traps that awaited women in royal marriage. She was the ex-sister-in-law of Spain’s Felipe II, from his marriage to her half sister Mary Tudor. Her father, Henry VIII, had beheaded her mother, Anne Boleyn. For her refusal to subordinate herself, she became known as the Virgin (meaning unmarried) Queen.

According to the writer remembered as John Taylor the Water-Poet, John Hawkins was the first person to bring tobacco to England, but it was popularized by Elizabeth’s favorite, Sir Walter Raleigh.25 An Englishman who owned extensive tracts of land in Ireland, Raleigh was the fashionable figure who popularized “tobacco-drinking,” as it was called at first, puffing away on his long-stemmed silver pipe even in the presence of the snuff-dipping queen. When the Virgin Queen awarded Raleigh a charter in 1584 to a broadly defined area of North America, he named it Virginia in her honor.

Unlike the Spanish colonies, which were developed as state projects and were often named for saints, Virginia was a commercial enterprise from the start, and its first colony, Roanoke, was named for money. Rawrenock, as Captain John Smith spelled it, was the medium of exchange used by the Pamunkey people who lived there: “white beads that occasion as much dissention among the salvages, as gold and silver amongst Christians,” Captain Smith wrote.26 The settlement was founded in 1585 on an uninhabited island off the coast of present-day North Carolina that gave signs of having previously been the site of a massacre.

Virginia was a challenge to Spain’s hegemony in the Americas. Pushed by a “war party” among her advisers—advocates of North American colonization who were locked out of commerce in the Americas by the Spanish monopoly—Elizabeth authorized Francis Drake to conduct a 1585–86 raiding expedition to the West Indies. To accomplish his mission, Drake outfitted a large fleet of some twenty-five sailing ships and at least eight pinnaces (smaller oar-and-sail combos, used for boarding and reconnaissance). He press-ganged some of his crew, but captains were eager to serve under England’s great sailor, warrior, profiteer, and anti-papist.

Shortly after setting out, a fever killed hundreds of Drake’s men, but his surviving force sacked towns on the Cape Verde islands. Then, according to one sailor’s account, on New Year’s Day 1586 he landed a thousand men some “9 or 10 miles distant from the Towne of Saint Domingo, the same day our men (by Gods helpe) tooke and spoyled the Towne.”27 To dramatize their ransom demand, the English burned between half and two-thirds of Santo Domingo, starting with the poorest parts of town. They hanged two friars, took everything of value, and remained there a month before pushing on to Cartagena de las Indias in Nueva Granada (today Colombia), which they likewise “spoyled,” tormenting the Cartagenans for six weeks before moving on.

In both Santo Domingo and Cartagena, they burned Spanish galleys; a Mediterranean naval artifact out of place in the Caribbean, the ships were slower-moving and clumsier than Drake’s vessels. They freed hundreds of galley slaves, some of whom joined Drake’s forces—a motley crew that included Africans, Turks, Frenchmen, and Greeks.28 Coming up the Gulf Stream along the coast of Florida, Drake spotted the watchtower of San Agustín, established twenty-one years before, and paused to allow his two thousand or so men to sack and burn the town.

Proceeding north, Drake’s final stop on his American tour was the queen’s colony of Roanoke. But when he arrived there, the colony was failing. He carried 105 dejected colonists home to England, so when Admiral Richard Grenville arrived with a supply ship shortly after, he found the colony abandoned. Leaving behind fifteen men, Grenville returned to England. When a second attempt at colonization with 150 colonists arrived in 1587, they found the colony abandoned yet again.

Drake’s campaign was not a profitable expedition for its joint-stock investors but it was costlier still for Spain, systematically dismantling as it did Spain’s defenses and ports. After his assault, “every sail upon the horizon conjured up the memory of Drake” for the Spanish in their system of fortresses that they called llaves (keys).29 It was the beginning of eighteen years of war between the two countries, during which England was allied with the Dutch.

Bent on retaliation for Drake’s depredations, the Invincible Armada of Spain sailed for England in 1588, but it went down to humiliating defeat. First there was a devastating storm that was widely seen in England as God’s intervention against popery and the Irish, then a battle in which England’s use of signaling beacons, constructed at strategic points along the coast, revolutionized naval communications. The defeat of the armada marked the ascension of England to the status of world power and brought a knighthood for John Hawkins. An innovative shipwright, he was effectively the founder of the English navy, which grew out of picking at Spain piecemeal.

One casualty of the Anglo-Spanish war was the Roanoke settlement: no supplies could be shipped to the colonists. By the time a ship arrived in 1590, three years after the previous supplies had landed, they had disappeared once again. There has been much speculation over the centuries about the fate of the mysterious “lost colony,” but the simplest explanation is that they were killed by the Pamunkeys under Chief Powhatan, whose territory they were invading; according to Samuel Purchas, Powhatan “confessed” to Captain John Smith “that he had bin at the murther of that Colonie.”30

Virginia had failed on its first try.

In the wake of Drake, Spain began building up its American fortifications to withstand future assaults. But in defending its positions on the mainland and the “vital artery of the treasure route,” writes Kenneth R. Andrews, most significantly meaning Havana as well as Lima, Portobelo, Cartagena, and Veracruz, “this inevitably meant that eastern Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles, though by no means abandoned, were more and more exposed to all forms of infiltration and attack.”31 Menéndez launched a newly formalized Spanish treasure fleet in 1566; that same year the Protestant Dutch, who had been under occupation by the Hapsburgs since 1482, launched a war for independence from Spain that dragged on in one form or another for some eighty years.

Spain claimed a monopoly on commerce and shipping in the Americas, but its fortress colonies were increasingly being visited by freelance merchant-warriors from other nations, who often acquired their goods by piracy and wanted in on the mercantile action, drilling into the Spanish monopoly like so many termites. The Dutch, who with their shipping industry were creating the world’s most dynamic economy in the Netherlands, made a grand business of attacking Spanish shipping. As the Anglo-Spanish war heated up, English privateers hammered at Spanish merchants and treasure ships, with profits accruing to the underwriters, who were often London merchants.

Drake and Hawkins made the mistake in 1595 of attacking the early version of San Juan’s formidable, well-defended Morro Castle, whose gunners and cannoneers had every possible angle of fire. The two despoilers of cities died in the aftermath of the assault, apparently of dysentery.

Elizabeth unified church and state under her sovereignty, formalizing the existence of the Church of England (or Anglican, or Episcopal church), which Henry VIII had broken out from the Catholic Church in 1534. The Anglican church retained much from Catholicism, but without the pope, without saints, and without the veneration of the Virgin Mary. The Lutherans and Calvinists thought the Anglicans corrupt, and the Catholics thought them heretical. While Elizabeth prioritized the avoidance of religious civil war in England, she brutally completed the conquest of Catholic Ireland that Henry had left unfinished, in a campaign that saw Spain side with its Irish co-religionists against England.

Elizabeth became alarmed by a small but increasing number of black people visible on London streets, and she ordered them deported in 1601, decrying the “great numbers of Negars and Blackamoors” in her kingdom and characterizing them as “Infidels.” She did not succeed in removing them, but she did establish a precedent in England for separating black people from others.32

Elizabeth died—unmarried, as per her vow, and without issue—in 1603 after a forty-four-year reign. She took no part in choosing her successor, but advisor Sir Robert Cecil had negotiated a succession pact in favor of her second cousin, James Stuart, who had been crowned James VI, King of Scotland at the age of thirteen months. James had been raised as an Anglican; his Catholic mother, the conspiratorial Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, had been beheaded on Elizabeth’s reluctant orders in 1567 after eighteen years of imprisonment, in a botched execution that required three ax strokes to completely sever her head. James was considered a foreigner by the English, but no matter: at the age of thirty-seven he succeeded Elizabeth as King James I of England.

Elizabeth bequeathed James a much more powerful country than the one Henry VIII had left her. Elizabethan England had beaten Spain, finished the subjugation of Ireland, and—not the least of its achievements—stabilized the pound sterling. The House of Stuart, however, proved to be, as one historian succinctly put it, “Europe’s most hapless dynasty.”33 Unifying the English and Scottish crowns, James was the first of a line of Stuart monarchs who would enrage Parliament.

Despite the black people of London having been singled out as a distinct and undesirable class by Elizabeth, their presence was changing notions of style in the city. A fashionable white fascination for blackness was particularly visible in the worlds of art and music, as on Twelfth Night, January 6, 1605, when James’s court attended The Masque of Blackness, written by Ben Jonson at the request of James’s wife, Queen Consort Anne of Denmark. “It was her majesty’s will to have them blackmoors at first,” wrote Jonson by way of introduction; the ladies of the court who performed in the cast were dressed in high style—which was the point of the exercise—as Africans, with their faces blacked.

*In Spanish the self-emancipated were called cimarrones, a word deriving from the Taíno language that became marron in French and maroon in English.

*Which group Ribaut encountered is unknown.

*The daughter of Henry VIII, she acquired the nickname “Bloody Mary” by burning 283 Protestants at the stake in 1555 during the revolt that followed her marriage to Felipe; Felipe effectively left the marriage in 1556 when he assumed the throne of Spain, leaving Mary without an heir and thus halting her project of re-Catholicizing England.