9

9 9

9A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse.

CHEW IT, SNORT IT, smoke it—any way you use it, tobacco gets you high.

Native Americans used it for ceremonial and medicinal purposes, but now an increasing number of Englishmen and women wanted regular doses of this addictive drug, imported or smuggled in from Spanish territories and sold in small quantities for a high price.

Londoners began getting hooked on what they called sot-weed, for the way it intoxicated the smoker. So much money was spent on it that the balance of trade between Spain and England was affected. Spain guarded its tobacco monopoly jealously, but John Rolfe obtained the seed of a strain that grew in the Spanish colonies of Venezuela and Trinidad. It was industrial theft: Rolfe convinced a sea captain, who would have been hung by the Spanish had he been discovered, to smuggle the tiny seeds to him from Trinidad. Once Rolfe was himself planted in Virginia, he began raising his crop, naming his plantation Varina after the tobacco strain; it is still a working farm in Virginia today.

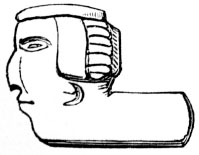

Indian tobacco pipe from Virginia. From Fairholt.

With Rolfe’s first successful crop of tobacco in 1612, Virginia found its staple. Instead of providing delicacies for England’s wealthy with olive groves and vineyards, the Virginians began supplying cheap, strong-smelling, habit-forming weed to the plebes. The tobacco the Virginians grew was universally accounted inferior to the leaf of Hispaniola, Cuba, Trinidad, Puerto Rico, or Venezuela, but it cost less.

Colonists quickly went over to cultivating the leaf. Tobacco required land and labor but not a fortune to get started, and it remained the most important American cash crop throughout the colonial years. The market was at first modest, but it swelled. Virginia’s production reached thirty million pounds by the end of the seventeenth century, and one hundred million pounds fifty years later.

Its widespread availability created a mass consumer culture in England. People were willing to work to have the money to buy tobacco, although, as the anti-tobacco King James ruefully (and correctly) noted, many a man had been known to “smoke himselfe to death with it.” James hated tobacco no less than he hated Raleigh, whom he ordered beheaded in 1618. Meanwhile, the English consumers’ new nicotine habit sustained the colonial economy that brought it to them.

Rotterdam 1623: expelling smoke through the nose was the fashionable way to smoke. From Fairholt.

When the new “partners” of the Virginia Company arrived in America, they found to their dismay that they were conscripts, coerced into gang labor under martial law. Everything they produced was to belong to the company, so they had no incentive to work.

Half or more of them died shortly after arrival. As word got out that Virginia was a death trap, agents, popularly known as “spirits,” went combing the streets for potential indentured servants for the colony—a process that included abducting children, bringing the phrase spirited away into popular usage, as well as the word kidnap.1 Some two hundred boys were taken from London in 1618, while groups of young women were dispatched in 1619 to provide wives for colonists; company officials were instructed to see that the women were not married against their will.2

Many of the desperately poor who went to Virginia were urbanites from London or Bristol, England’s second city.3 There were indentured servants in England, but their term was a year and they received a wage. In Virginia, the term was between four and seven years, and the wages were paid up front in the form of a ticket for a transatlantic crossing.4

The conditions of those crossings were described in a 1623 letter from Virginia that, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, provides the first known instance of the much older word funke as meaning “a strong smell or stink”: “Betwixt decks there can hardlie a man fetch his breath by reason there ariseth such a funke in the night that it causes putrefaction of bloud.”5 This was not a description of a slave ship; they smelled even worse.

Realizing that there was little reason to come to Virginia and little incentive beyond mere survival to work hard once arrived, Virginia governor Thomas Dale threw open the door to private land acquisition in 1616, hoping to stimulate growth. He offered a good deal: the “old planters” who were already there got a hundred acres each, along with another hundred acres if they were company shareholders. Newcomers got fifty acres.

The colony had begun as a commons under military discipline, but by changing its regime to one in which individual colonists could become landowners, Dale created a real estate market, which in turn quickly became a land grab.6 But the land was worthless without labor. It now fell to individual entrepreneurs, not the Virginia Company, to address the labor problem in Virginia, and by 1617 the company was allowing semi-independent plantations, called “hundreds,” which transported their own labor.

Indentures were probably under way in Virginia by 1617, but the first extant contract of indenture that has come down to us, issued by the Virginia partnership called the Berkeley Hundred, is dated September 17, 1619. That year, the colony’s secretary John Pory wrote to London: “All our riches for the present doe consiste in Tobacco, wherein one man by his owne labour hath in one yeare raised to himselfe to the value of 200£ sterling; and another by the meanes of sixe servants hath cleared at one crop a thousand pounds English.”

Then, as if thinking it through as he was writing, Pory corrected himself in the same paragraph:

“Our principall wealth (I should have said) consisteth in servants.”7

Workers were already capital assets.

Planters rarely imported specific indentured servants. Upon arrival, the survivors of the voyage were displayed in a market and—they used the word—“sold.” John Harrower, the Scottish indentured servant who left a journal of his tragically short life in Virginia, recalled the scene on May 16, 1774, still aboard the ship that brought him to Fredericksburg, Virginia; interestingly, he used the term “soul driver,” more commonly associated with the slave trade:

This day severalls came on board to purchase servts. Indentures and among them there was two Soul drivers. They are men who make it their bussines to go on board all ships who have in either Servants or Convicts and buy sometimes the whole and sometimes a parcell of them as they can agree, and then they drive them through the Country like a parcell of Sheep untill they can sell them to advantage.8

This manner of labor distribution uncomfortably reminded some of the slave markets of the Muslim world, which those with military backgrounds might possibly have encountered (or, as in the case of Captain John Smith, been sold in).

Planters had a sweet deal, known as the “headright” system: they were given fifty acres of land for every indentured servant whose passage they paid—so they not only got the benefit of several years of wageless labor, but also received the land to do it on. This facilitated the acquisition of large tracts of land by those with even modest amounts of capital. Headrights could be sold; by the 1650s, they were being traded for as little as forty or fifty pounds of tobacco.9 A real estate market had been created out of enclosed Virginia land, with any claims of sovereignty by Native Americans instantly discarded.

The urban poor who came as laborers were unskilled and unaccustomed to agricultural work. The descendants of multiple malnourished generations, they were not physically strong enough for the backbreaking task of clearing what George Washington would call “this wooden Country,” and their mortality rates after arrival were dreadful.10 They were, however, sufficient to amass large landholdings from headrights for those with the capital to sponsor them as land speculation began.

John Rolfe is most remembered in popular history not for his pioneering of Virginia’s great staple crop but for having married Pocahontas, a daughter of the Pamunkey chief Powhatan.

Pocahontas had learned English after being kidnapped by the Jamestown settlers in 1613, during which time she was Christianized and renamed Rebecca. As a prosperous tobacco farmer, Rolfe traveled to London in 1618 together with Rebecca/Pocahontas and their infant son, Thomas, but she fell ill and died while preparing to return to Virginia. Fearing his son would not survive the voyage, Rolfe reluctantly left him in England and returned to America.

Back in Virginia, Rolfe documented, rather off-handedly, the first known sale of African slaves in Anglo-America, from a passing Dutch vessel. One day “about the latter end of August” in 1619, as Rolfe described it in his historic letter of January 1620 (modern calendar) to Sir Edwin Sandys of the Virginia Company:

a Dutch man of Warr of the burden of a 160 tunnes arriued at Point-Comfort…. He brought not any thing but 20. and odd Negroes, wch the Governor and Cape Marchant bought for victualls (whereof he was in greate need as he pretended) at the best and easyest rates they could.11

It was a good deal for the purchasers, and, since the seller got some much-needed food, perhaps a good deal for the seller as well. But if it was a win-win for buyer and seller alike, it was at the expense of those who were bought and sold.

Historians ever since have wished Rolfe had provided more detail. These were not, as has sometimes been claimed, the first black people to come to Virginia; a census five months earlier counted thirty-two.12 Nor were they the first slaves whose sale was documented. Already in The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles, John Smith had noted an inter-Indian slave trade of sorts, though it overlapped with the concept of marriage. Powhatan, Pocahontas’s father, had sold a daughter of his, and Smith chided him for underpricing:

[Powhatan said,] “I have sold [my daughter] within this few days to a great Werowance, for two bushels of rawrenoke, three days journey from me.”

I replied … she was but twelve years old … he should have for her three times the worth of the rawrenoke in beads, copper, hatchets, &c.13

The supremacy of Dutch maritime commerce was a mark of shame for the English. In a report submitted to King James, Sir Walter Raleigh had noted that the Dutch “have a continual trade into this kingdom with five hundred or six hundred ships yearly with merchandize of other countries … and we trade not with fifty ships into their country in a year.”14

“The establishment of the American settlements,” writes Philip A. Bruce, “was the first step on the part of the English people towards a successful competition with the Dutch merchant marine.”15 England was a heavy importer of raw materials from other European nations, for which it had to pay in scarce specie. Opening up North American colonies would make a whole array of products cheaply available to them: tar and pitch, salt and potash, iron and timber, hides and pelts.

It was not unusual for the Dutch to be nosing around the Chesapeake. In flagrant violation of England’s rules, they carried Virginia and Maryland tobacco to their market in Amsterdam and gave better prices for peltry. The Dutch merchant fleet and credit services were far and away the world’s most advanced. But as their commercial power grew globally, carrying goods was no longer enough for them, and they moved toward vertical integration.

The Dutch, who were not yet trading in slaves on an industrial scale, could not attack the Portuguese under the terms of their Twelve Years’ Truce with Spain (1609–1621), because Portugal was under the Spanish crown between 1581 and 1640. But they occasionally sold slaves who had been taken as prizes from Portuguese slavers by English privateers. John Thornton argues that the “20. and Odd Negroes” were Kimbundu-speaking soldiers from Angola, captured during the large, formalized military campaigns of a war waged by the Portuguese against the kingdom of Ndongo.16 Historian Engel Sluiter provides evidence that they were nabbed by an English corsair in a raid on a Portuguese ship on its way to Veracruz.17 The raided cargo was then presumably swapped over for commercial liquidation to that “Dutch man of warr” (with an English “Pilott”) that visited Jamestown in August 1619.

If so, the “20. and Odd” would have been Catholic, at least nominally. Some of them probably spoke some Portuguese.

Ruin of the Catholic church of São Salvador do Congo, known in Kikongo as kulu mbimbi, “strong place,” built in 1491 at the royal seat of Mbanza-Kongo, in present-day northern Angola. July 2012.

Central Africa was Catholicized in 1491—before Columbus crossed the Atlantic —when the manikongo (Kongo king) Nzinga a Nkuwu at his hilltop capital of Mbanza-Kongo converted—not at sword’s point, but enthusiastically and immediately upon the arrival of two missionaries. The manikongo, who ruled the largest empire in Africa at the time,* accepted baptism and became King João I.

João seems to have grasped immediately the political uses of Catholicism. Converting his territory gave him a powerful new set of tools to establish his hegemony over the freelance priesthood of traditional Kongo religion, as well as allying him with powerful European patrons and giving him access to previously unknown manufactured goods, most especially including guns.18 Building churches throughout his vast kingdom, he established diplomatic relations with the Vatican.

The symbols and beliefs of Catholicism merged well with the symbols of traditional Bakongo religion, creating a syncretized version of Catholicism that was compatible with existing Kongo cosmology and continued ancient practices, which were arguably no more superstitious or magical than fifteenth-century Catholicism. The Bakongo already had a cross—the dikenga—a cosmogram that signified the meeting in time of the land of the living with the land of the dead on the other side of the water. It was a midpoint cross, not a chest-high crucifix, but it was recognizable. The Bible that the priest revered was, to the Bakongo, clearly an nkisi—a power object.

As Central Africans became the most numerously slaved people of the African trade, the Kongo-Catholic syncretization—a “fully Africanized” Christianity, in Thornton’s words, which came into existence before the Middle Passage—was transported to all points of the Americas, serving as a fundamental backbone of African culture in the Americas.19 It took root easily in the Catholic territories established by Spain and Portugal, which would lead to enslaved Bakongo being suspected in the English colonies as potential allies of the Spanish.

Rolfe went on in his “20. and odd” letter to describe the colonists’ fear of Spanish attack in the coming spring:

wee have no place of strength to retreate unto, no shipping of certeynty (wch would be to us as the wodden walles of England) no sound and experienced souldyers to undertake, no Engineers and arthmen to erect works, few Ordenance, not a serviceable carriadge to mount them on; not Ammunycon of powlder, shott and leade, to fight 2. wholl dayes, no not one gunner belonging to the Plantaccon.20

By that time, the Anglo-American tobacco economy in Virginia was well into a debt-driven boom, with interest typically at 6 percent per annum. With credit, people drank up the profits, then ordered another round. “The first legislative assembly in Virginia in 1619 felt obliged to pass acts against excess in apparel and also against drunkenness,” writes Edmund S. Morgan. “The thirst of Virginians became notorious in England…. The ships that anchored in Virginia’s great rivers every summer were, as one settler observed, moving taverns, whose masters, usually private traders, got the greater part of the tobacco that should have been enriching the colonists and the shareholders of the company…. There were sometimes as many as seventeen sail of ships to be seen at one time in the James River.”21

The colonists on occasion starved. Maybe it was self-destructive depression under the harsh conditions, or maybe the sheer ineptitude of their gentry-heavy colonial population. But you could also blame it on the weed: they were so determined to grow tobacco that they neglected to grow food. Colonists were officially required to cultivate a plot of corn, but many ignored the law and relied instead on the Native Americans to do the base labor of raising corn while they chased tobacco riches, but the natives didn’t always want to sell their corn to the colonists, so sometimes the Virginians went and took it.

The income that in theory accrued to the Virginia Company was being systematically drained away by its shamelessly corrupt officials, who repressed dissent brutally as its investors lost money and colonists died of diseases, mysterious distempers, and violence. A massacre commanded by Pocahontas’s uncle Opechancanough killed about a third of the colonists and kidnapped twenty women in more than thirty separate surprise attacks on March 22, 1622, with the aim of driving the English out. The ailing John Rolfe was a victim of the campaign: one of the raids destroyed his plantation, after which he died, though whether from violence or from illness is unknown.

That massacre, along with the concomitant destruction of productive facilities, was followed by yet another starving time. With fewer than a thousand colonists still alive, King James rescinded the Virginia Company’s charter, reverting the colony to royal status—a decision that earned James the vituperation of future Virginia historians. Edmund S. Morgan, in his landmark history of slavery in Virginia, responded: “Because the Stuart kings became symbols of arbitrary government and because Sir Edwin Sandys [one of the proprietors of the Virginia company] was a champion of Parliamentary power and was even accused at the time of being a republican, historians for long interpreted the dissolution of the Virginia Company as a blow dealt to democracy by tyranny. Modern scholarship has altered the verdict and shown that any responsible monarch would have been obliged to stop the reckless shipment of his subjects to their deaths.”22

Colonial development in Virginia was going to be a long-term investment, far longer than the timetables of profit could hold out for. By the time the rescission of the Virginia Company’s charter became final in 1624, investors in the company had lost £200,000 and more than three-fourths of the six thousand or so people who had emigrated since 1607 were dead.23

And by the following year, so was King James. But not before he empowered an enemy of Virginia.

In his capacity as King James’s secretary, George Calvert was the monarch’s man in Parliament to defend the proposed “Spanish match,” the never-achieved royal marriage of James’s second son, Charles, to Hapsburg princess Maria Ana, daughter of Felipe III. The idea that Charles might take a Spanish-Austrian Catholic bride horrified the Puritans in Parliament. King James’s older son, Henry, known for his upright Protestant morality, had been the great popular hope of the Puritans, but he died in 1612 at the age of eighteen, leaving younger brother Charles in line for the throne.

In the end the Spanish princess would not marry a Protestant, and though Charles traveled to Spain to court her, he would not convert to Catholicism, so the marriage never came to pass. But the fallout from the affair led to a deterioration of relations between England and Spain, followed by war. It also left Calvert on the outs politically. He resigned his position and came out of the closet as a Catholic. James rewarded Calvert for his services, and got him out of the way, by awarding him a barony in northern Ireland and a title in the Irish peerage: Lord Baron of Baltimore.

Then Charles, the future king of England, scandalized the Puritans by marrying a French Catholic Bourbon princess, Henrietta Maria de Medici. That’s Maria as in the Virgin Mary, and also as in the territory that was named for the new queen consort: Maryland.

*Reaching from present-day Gabon to present-day Zambia.