10

10 10

10Does my hair trouble you?1

IN HER MARRIAGE CONTRACT, the fifteen-year-old Queen Consort Henrietta Maria was guaranteed the full practice of her Roman Catholic religion, which enraged the Puritans.

Born in 1609, nine years after her father King Henri IV’s Edict of Nantes provided civil guarantees for French Protestants, Henrietta Maria came from France to England with a mission of spearheading Catholic power by means of strategic marriage. She had learned the art of queening at the knee of her mother, Marie de Medici, who commissioned a series of twenty-six allegorical paintings depicting her life from the prolific Peter Paul Rubens.

She brought with her from France eleven liveried musicians and three singing boys, who performed sacred music composed for her. The English crown was considerably less affluent than the French, and Henrietta Maria’s retinue was smaller than the Bourbons were accustomed to in France, but it was large enough that her household staff included a “keeper of the parrots” and two dwarves, Jeffrey and Sarah, both of whom had servants.2 “Pet” dwarves were common figures in royal courts, but in the case of Charles and Henrietta Maria, they had the function of making the monarchs look bigger: Charles was five foot four, and Henrietta Maria was so short she only came up to his shoulder.

England began its slide to civil war in 1629 when Parliament, with strong Puritan representation, refused to convene. For the Puritans, having a Catholic queen was a dreadful infamy; they saw Charles as soft on popish Spain. By that time, England’s monarch had deferred to Parliament for over three hundred years, but now Charles attempted to run England without Parliament, a standoff that lasted eleven years. During that period the royals also had a tense relationship with William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who persecuted both Puritans and Catholics while discharging his responsibilities as head of the twelve-member Lords Commissioners for Foreign Plantations.

The ensuing migration of Puritans to America defined one of the principal power blocs of future American politics, as approximately twenty thousand dissenters came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1630s. Unlike most other immigrants to the Americas, these were not single young men, but families. Many were relatively prosperous, and the community they built was stable, productive, and repressive.

Puritan New England, a culture of literate, industrious, small farmers, was on guard against tyranny and against witchcraft—which, for them, included Catholicism. There was no doubt: the Antichrist was the pope, and the Spanish were his henchmen. Immigrants had to be formally admitted to New England: the Puritans required letters of recommendation for potential colonists, who could only be part of the Calvinist New England Congregationalist Church. They were anti-episcopal (didn’t have bishops), and they were intolerant of the episcopal Anglicans, as well as of the Quakers, to say nothing of Catholics.

In 1629, the same year that Puritans began fleeing to New England, George Calvert, now titled Lord Baron of Baltimore, asked Charles I for a land grant. His short-lived Avalon colony in Newfoundland had been defeated by a harsh winter. Now he wanted the territory belonging to Virginia on both the western and eastern banks of the upper Chesapeake, as mapped out by Captain John Smith. He pitched the charter as providing a buffer zone to protect His Majesty’s grand Chesapeake Bay from encroachment by the Dutch and Swedish. The former had founded Nieuw Amsterdam in 1625, while the latter, colonizing parts of what later became Delaware and Pennsylvania, named a river and a settlement after the Swedish Queen Christina.

If the Swedish queen had a settlement named in her honor, what homage befit the queen of England?

Calvert died only weeks before his land grant was finalized, but it was bestowed on his son Cecil Calvert, who inherited his title. Writing in Latin, a priest gave an account of the colony in 1633, before the first colonists had sailed: “The Most Serene King of England desired that it should be called the land of Maria or Maryland, in honor of Maria, his wife. The same Most Serene King, out of his noble disposition, recently, in the month of June, 1632, gave this Province to the Lord Baron of Baltamore and his heirs forever.”3

Praying to the Virgin Mary was a razor-sharp dividing line between Catholics and Protestants, the former of whom saw it as a mystical experience and the latter of whom saw it as idolatry. Virginia had been named for the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth, whose Church of England had removed the worship of the Virgin Mary from its liturgical calendar. Now there would be another Virgin-inspired queen-named colony in the typhoidal swampland—this one appropriate for Catholic pioneers, for whom Marianism was at once a religious and political imperative.

Mary’s Land was to be tolerant, but Maryland would not be Catholic turf the way the Spanish domains were. Quite the contrary: Maryland was officially Anglican, the majority of its colonists were Anglican or Protestant, and no Catholic church was actually established there, though Jesuits manned missions.

Never again would the Chesapeake be under the control of a single entity. Its division into upper (Maryland) and lower (Virginia) affected everything from the cultivation of tobacco—the two colonies could never coordinate how much they would produce or even what the standard measure was—to the two territories’ opposing status in 1861, when Virginia went Confederate while Maryland remained in the Union.

The first Maryland colonists arrived in 1634 on the Ark, traveling via the Antilles. The priest Andrew White, who crossed the Atlantic with them, wrote in his journal that “we came before [the island of] Monserat, where is a noble plantation of Irish Catholiques whome the virginians would not suffer to live with them because of their religion.”4 This first known written instance of the word “virginian” was, significantly, used in connection with Virginia’s intolerance. Virginia was officially Anglican and remained intolerant until independence, although Virginia was not settled by religious dissenters and was not particularly pious. “With no resident bishop and only a handful of ministers to watch over its rowdy, scattered populace,” writes Paul Lucas, “seventeenth-century Virginia became noted for its lack of religiosity.”5

“As for Virginia, we expected little from them but blows,” wrote Father White. When they arrived, he was impressed by the “Patomecke” (Potomac) River, which the new colonists attempted to rename St. Gregory’s; it was, he wrote, “the sweetest and greatest river I have seene, so that the Thames is but a little finger to it.”6

Father White brought with him a Portuguese-surnamed indentured servant of African descent, Mathias de Sousa, described as a “molato,” along with another “molato” named Francisco, so free men of color—albeit indentured—were among the founders of the colony. Father White assigned his headrights to one Ferdinando Pulton, who claimed land grants based on the importation of twenty-one people.7

The Virginia colonists were already insolent. In a 1634 letter written from Jamestown, Captain Thomas Yong of the Maryland expedition wrote, “I have bene informed that some of the [Virginia] Councellors have bene bold enough in a presumptuous manner to say, to such as told them that perhaps their disobedience might cause them to be sent for into England, That if the King would have them he must come himself and fetch them.”8

Virginia was by that time relatively stable. Its food problem had largely been solved by the successful establishment of large herds of cattle and especially hogs, which can have two or more litters a year of up to a dozen piglets at a time. With so much land available for pasturage, raising meat animals was practical, and the easy availability of high-quality protein from meat and dairy products may have been the salvation of the Virginia colony.

Virginia was impresarial, its founding the work of a corporation with investors, but Maryland was a proprietorship. Lord Baltimore owned it. A number of counties in Maryland are named for his family members: Calvert (the family name), Cecil (for Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore), Charles (for Charles Calvert, the third Lord Baltimore), Anne Arundel (Cecil Calvert’s wife, Charles Calvert’s mother), and Talbot (Lady Grace Talbot, Cecil Calvert’s sister).

Written in Latin, King James’s charter granted to Lord Baltimore the hactenus inculta, or uncultivated lands, “partly occupied by Savages, having no knowledge of the Divine Being.” As compensation, the king and his heirs and successors were to receive (according to contemporary translation) “TWO INDIAN ARROWS of those Parts, to be delivered to the said Castle of Windsor, every Year, on Tuesday in Easter-week; and also the fifth Part of all Gold and Silver Ore, which shall happen from Time to Time, to be found within the aforesaid Limits.”

The Maryland charter covered both shores of the upper Chesapeake, creating a territory divided into two parts by water. The “western shore” and the “Eastern Shore” of Maryland do not meet, but must connect across water.* The Virginians had the Chesapeake’s four great rivers in their territory, though they were not yet fully navigable—from south to north, the James, the York, the Rappahannock, and the Potomac. Maryland occupied the northern bank of the Potomac, but never attempted to navigate it commercially.

Calvert’s territory did, however, have a grand harbor on its western shore. It would not be of much use for transatlantic traffic, but would later be the commercial powerhouse of the Chesapeake’s communication with the westwardly expanding domestic market: Baltimore.

The Virginians were too few in number to have occupied the Maryland territory, but William Claiborne (or Clayborne, or Clairborne), a Virginian from Kent, England, was already invested in the territory and opposed Baltimore’s plan. Claiborne, a member of the Virginia Council, had named and claimed proprietorship of Kent’s (or Kent) Island, which sits in the middle of the Chesapeake adjacent to the Eastern Shore. He focused not on planting tobacco but on fur trading, which obliged him to have good relations with the Native Americans. Claiborne insisted that the charter’s language could not apply to Kent Island, to which he asserted ownership rights. Planning for the island to be the hub of a mercantile empire he would build, he had convinced settlers to move there and plant it with orchards and vines. He set up a shipyard, where he had the pinnace Long Tayle built in 1631, three years before the arrival of Lord Baltimore’s colony—“the first boat built solely on the bay,” writes Frederick Tilp.9

The first naval battle in the Anglo-American colonies took place in 1635 between Maryland and Virginia, when Lord Baltimore’s pinnaces defeated Claiborne’s vessels at the entrance to the Pocomoke River.10 Claiborne attempted various times to get back what he considered his land, through military conflict and diplomatic wrangling, but he ultimately relinquished the struggle in 1657 after an intra-Chesapeake hostility that lasted more than twenty years. Remembered as the champion of Virginia’s former grandeur, he was the founder of a still-prominent family line of politically connected American bluebloods that includes his great-great-grandson W. C. C. Claiborne (the Virginian who was the first American governor of Mississippi and Louisiana).

Perhaps it was Calvert’s experience with the failed colony at Newfoundland that led him to issue and enforce instructions to his colonists to grow food crops for themselves: “that they cause all the planters to imploy their servants in planting of sufficient quantity of corne and other profision of victuall and that they do not suffer them to plant any other comodity whatsoever before that be done in a sufficient proportion wch they are to observe yearely.”11

Plantations were anything but self-sufficient in food. As John Smith explained to a royal commission, “Corne was stinted [valued] at two shillings six pence the bushell, and Tobacco at three shillings the pound; and they value a mans labour [in tobacco] a yeere worth fifty or threescore pound, but in Corne not worth ten pound.”12 The capital-intensive nature of a plantation required the dedication of all land to maximum financial return, with supplies imported and paid for on credit. But Lord Baltimore’s insistence that “Mary’s Land” raise its own “victuall” implanted from the beginning a culture of expert and varied cultivation in the colony, with long-range consequences for the state’s high-quality food supply.

Maryland put itself to the cultivation of tobacco from early days, with the result that Virginia planters had competitors who could be expected to increase production if they held back.

New England (Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and, later, Vermont and Maine) never developed a staple crop, or a plantation system. New England had slavery in the colonial years, but unlike Virginia, it never became a slave society, in which all social and economic relations revolve around slavery. One of the first slaveowners in Massachusetts, Samuel Maverick, was the object of a complaint from a captive African woman whom he had force-mated with an African man; but without plantations, and cooped up in the limited space of houses in town, New Englanders did not engage much in slave breeding.13 New Englanders bought slaves, but mostly in small numbers: Africans (or creoles) from the Antilles and, later, Native Americans from Carolina, who were generally destined to be household, urban, or small-farm workers. Nor was New England a heavy consumer of indentured labor.

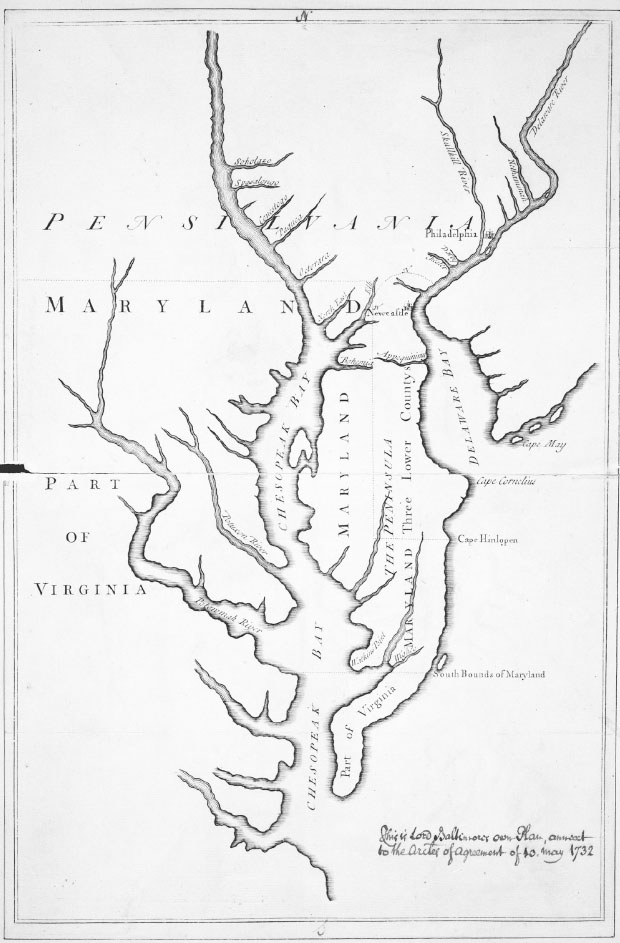

The Eastern Shore is prominent in this depiction of Lord Baltimore’s Maryland in 1732.

New England survived in its early days the way the French did in Canada: on the fur trade. Beaver pelts were a principal export, and King Charles provided a market for them all by himself. He particularly liked silk-lined beaver hats, worn with brightly colored hatbands, and bought them not only for himself but for his retinue. According to Nick Bunker, he bought “sixty-four beaver hats in 1618, fifty-seven in 1619, forty-six in 1623, and forty-three in 1624.” Bunker estimates that as the beaver hat became popularized as “an emblem of status” for the peerage and the landed gentry, a minimum of twenty-three thousand of them a year were needed to accommodate the demand.14

The small farmers of New England exported a variety of food and commodities, especially corn, and they diversified into becoming fishermen, lumberjacks, and shipbuilders, then developed into shippers, merchants, bankers, and insurers.

David Hackett Fischer’s tracing of four English folkways in America provides a model for appreciating the cultural contrast: 1) the Puritans of southeast and northeast of London, who moved to New England; 2) the Royalists of the south and west, who moved to Virginia; 3) the up-country Quakers, to Pennsylvania; and 4) the “Scotch-Irish,” to the Appalachians. Fischer surveys the demographics of England from which each migration came and demonstrates strong cultural continuity between locales on either side of the Atlantic, each of which would develop into a distinct political tendency in the independent American republic.

Slavery was not a new idea in English culture, particularly in the area from which the largest number of Virginia’s early populators came. “Virginia’s recruiting ground,” writes Fischer, “was a broad region in the south and west of England” of scarce urban development and large rural manors—an area where slavery had earlier (though no longer) existed for centuries, going back to the Roman era. “During the eighth and ninth centuries,” writes Fischer, “the size of major slaveholdings in the south of England reached levels comparable to large plantations in the American South. When Bishop Wilfred acquired Selsey in Sussex [in the late seventh century], he emancipated 250 slaves on a single estate. Few plantations in the American South were so large even at their peak in the nineteenth century.”15

The Puritans of New England and the Royalist Virginians, opposed to each other from the start, struggled to establish their respective colonies in America as the hatred between “Roundheads” (Puritans, so called because they cut their hair short, who in popular telling were commoners descended from Saxons) and “Cavaliers” (Anglicans, who wore their hair long and were said to be aristocrats descended from French Normans, who were in turn the descendants of Norsemen, or Vikings) erupted in 1642 into what has been remembered in England as the Civil War, which had a strong echo in America.

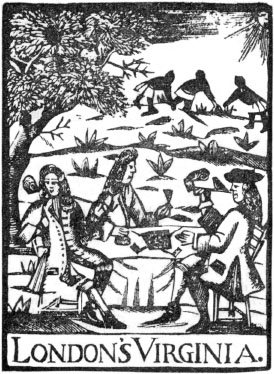

In this woodcut tobacconist’s card from ca. 1700, Virginia cavaliers drink and smoke while black slaves labor behind them. Images of Africans at work appeared in a variety of English tobacco advertising materials in the late seventeenth century, along with (not depicted here) Indians depicted with black skin, in tobacco-leaf skirts and headdress, overtly promoting as part of the product’s public image its origin as an “Indian weed” cultivated by slave labor in Virginia. From Fairholt.

The Puritans versus the Cavaliers: not coincidentally, in North America these words connoted the two power bases of New England and Virginia. The Royalist Virginia gentry, who were largely descendants of English family webs transferred to America, believed in aristocracy, hierarchical society, luxury, idleness, and servants. Their identification as “Cavaliers”—a word meaning “horsemen,” or, more broadly, “knights”—links them with the Spanish caballeros and the French chevaliers. Like them, the Cavaliers had the opposite of the Puritans’ work ethic. “Many Virginians of upper and middle ranks aspired to behave like gentlemen,” writes Fischer. “The words ‘gentleman’ and ‘independent’ were used synonymously, and ‘independence’ in this context means freedom from the necessity of labor.”16

The stringently religious Puritans did not gamble, but Virginia planters gambled compulsively. The Puritans suspected them of being Catholic sympathizers. By the 1630s, the more affluent Virginians were buying African slaves from Dutch traders on an ongoing basis, while Virginia frontier traders, who were something of a renegade element in the colony, enslaved and sold Native Americans.17

Henrietta Maria opened her chapel at Somerset House in 1636, after seven years of work. It was a safe place to attend Mass, and thousands did. It was also the height of fashion. The chapel hummed with motets commissioned from the queen consort’s preferred composers. Marian imagery was everywhere. “Visitors thronged to see the mesmerizing decorative scheme,” writes Erin Griffey, “replete with paintings and a special sacristy. Conversions of prominent courtiers and aristocrats, ladies in particular, were not uncommon in 1637. [Archbishop] Laud was incensed by the public scandal.”18 But pursuant to an anti-superstition act of the Puritan Parliament, Henrietta Maria’s chapel was destroyed by a mob of iconoclasts in 1643.19 They tore its crowning work, Rubens’s Crucifixion, into bits and threw the pieces into the Thames, along with the rest of the painting and sculpture the chapel contained.

By then, the English Civil War was under way. The Puritans, whose New Model Army was the first modern army in England, beat the forces of King Charles in 1645 and established the Commonwealth of England in 1649. Parliament carried out one of the most radical acts in all of European history when it tried, convicted, and, on January 30, 1649, killed the king. Remembering the botched execution of his grandmother, Mary Queen of Scots, Charles Stuart put his long Cavalier hair away from his neck into a cap to allow his executioner (a professional, brought from France for the occasion) a clean shot at his neck, and was successfully beheaded with a single stroke.

Once Puritans no longer feared persecution in England, out-migration to New England stopped as suddenly as it had begun. The region would not receive another mass migration for nearly two centuries. There was even a reverse migration back to England, since previously closed doors were now open to well-connected Puritan businessmen.

The Puritan regicide further poisoned the relations between Catholic and Protestant Europe. The designation of the ambitious New Model Army leader and king-killer Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland in 1653 began an era of intolerance, during which the execution of heretics increased and theaters remained shut down.

In Maryland, the colonial assembly passed the Act of Toleration in 1649 at the Calverts’ urging. The first law in the colonies concerning religious tolerance, it reiterated the tolerant policy that had been part of Lord Baltimore’s instruction from the beginning. But after a ten-man Puritan council headed by Maryland’s old nemesis William Claiborne took charge of Maryland in post-Cromwell 1654, a new law prohibited open practice of the Catholic faith.20 In 1658, Calvert managed to get the Act of Toleration reinstated. Still, on July 23, 1659, the council issued a directive to “Justices of the Peace to seize any Quakers that might come into their districts and to whip them from Constable to Constable until they should reach the bounds of the Province.”21

Quakers, who were antislavery and were therefore unwelcome, presented a new social and political problem for the nominally Anglican Cavaliers.22 The first seed of Quakerism was planted in Virginia in 1656 by the Londoner Elizabeth Harris, who remained in Virginia for a year or so and proselytized. Quaker George Wilson, who had been whipped from constable to constable through three different towns and banished from Massachusetts, arrived in Virginia in 1661 and was imprisoned until “his flesh actually rotted away from his bones,” in the words of a chronicler.23

Under the Puritans, Royalists fled England for Virginia and Maryland, an exodus that continued even after the Restoration of 1660. “From 1645 to 1665,” writes Fischer, “Virginians multiplied more than threefold and Marylanders increased elevenfold, while New Englanders merely doubled.”24

Other Cavaliers fled hostile Puritan England for the island of Barbados, where a different kind of revolution was in progress: sugar.

*By custom “Eastern Shore” is capitalized, but “western shore” is not.