11

11 11

11The genterey here doth live far better then ours doue in England; thay have most of them 100 or 2 or 3 of slaves apes [apiece] whou they command as they pleas: hear they may say what they have is thayer oune; and they have that Libertie of contienc [conscience] which wee soe long in England have fought for: But they doue abus it.1

THE ATLANTIC SUGAR PLANTATION system took shape in the late fifteenth century on the previously uninhabited island that the Portuguese called São Tomé, off the coast of Calabar, in the crook of Africa.

Settled by explorer Álvaro Caminha in 1493—the same year Columbus brought experimental sugar seedlings to the present-day Dominican Republic—São Tomé built on the previous model of Mediterranean sugar plantations but employed previously unthinkable quantities of labor to produce sugar on a new, large scale.2 The labor was available via São Tomé’s ready access to slave markets; it was a transshipment point for slaves headed to the Americas. By the 1550s, São Tomé had sixty sugar mills grinding, with individual plantations boasting workforces of as many as three hundred slaves.

The Portuguese applied the São Tomé model to create the first great sugar industry of the Americas in northeastern Brazil, where a full-scale planters’ aristocracy had entrenched itself by the mid-sixteenth century. There was one major difference, however: the labor force in Brazil was mostly made up of enslaved indigenous Brazilians, who quickly proved to be unsatisfactory laborers. In a pattern later replicated throughout the hemisphere, a transition began in Brazil to African slave labor.

Wanting in on the sugar plantation action, the Dutch captured São Tomé in 1598–99. While paused from attacking Spanish and Portuguese merchant vessels during the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609–1621), they built up their navy. They established Dutch outposts in North America, beginning in 1615 with Fort Nassau on the Hudson River and including, as of 1625, Fort Amsterdam—the future New York City—at the tip of Manhattan Island. With its defensive battery positioned on the site of present-day Battery Park, Fort Amsterdam provided protection for Dutch families who had been consolidated there from around the region.

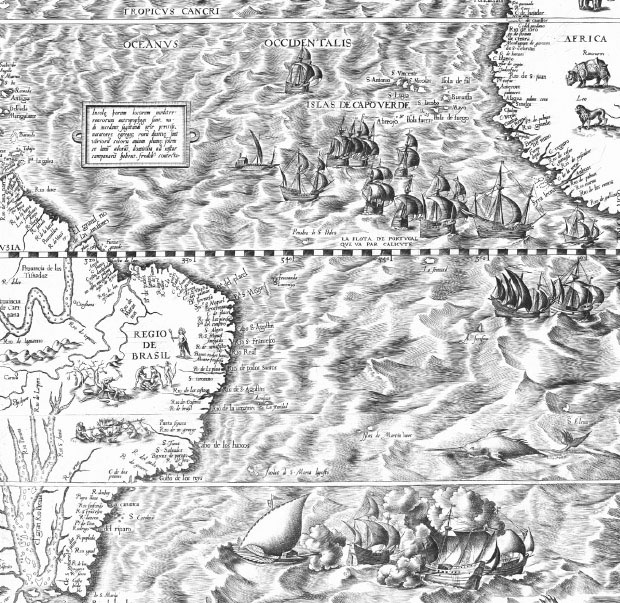

The relative closeness of Africa and Brazil is depicted in this detail from the first map of the hemisphere, a 1562 collaboration between Spanish cartographer Diego Gutiérrez and Dutch engraver Hieronymous Cock. In the ocean between the two, the Portuguese fleet is depicted on its way to “Calicute” (India). In the lower portion of the image, a naval battle is depicted.

Nieuw Amsterdam was from the beginning dense, secular, tolerant (with Jews both Sephardic and Ashkenazi), and multilingual. The colony’s first shipment of slaves, eleven in all, came in the colony’s second year, making it the second colony (after Virginia) in the present-day United States to import African slaves.

Slaves in Nieuw Amsterdam were corporately owned by the Dutch West India corporation. With time, they were manumitted and given land of their own, though they had to give a portion of their proceeds back to the company. On July 14, 1645, the free African Paulo d’Angola was granted a parcel of land on present-day Washington Square Park. Antony Congo was granted a parcel on the east side of the Bouwerie (from a point between present-day Houston and Stanton Streets to Rivington) on March 25, 1647. Francisco and Simon Congo were given nearby plots.3 They were exposed pioneers in a bad neighborhood, forming the buffer zone between the Dutch at the lower tip of Manhattan and the Native Americans to the north who might decide to raid.

As Dutch commercial policy became more aggressive, the Dutch fleet assaulted Portugal’s markets in Asia, then in the 1620s began a war for the European sugar market, which was principally supplied at that time by the two Brazilian centers of Salvador da Bahia and Recife in Pernambuco. They took Recife in 1641, though they could not hold Salvador.

From their vantage point in Brazil, the Dutch saw a double commercial opportunity nearby, on the English-controlled island of Barbados. In taking advantage of it, they created the Antillean sugar industry.

Barbados was easy for a seventeenth-century navigator to miss. Located in the Atlantic a hundred or so miles to the east of the arc of the rest of the Lesser Antilles, it’s a patch of land comprising only some 166 square miles. Off the main sea road, it was the farthest from the major Spanish bases in the Americas, and it offered a relatively easy sail to Europe.

Barbados means “bearded ones” in Spanish, though why the island was called that is a mystery. The Spanish had claimed the unoccupied island in 1511, but it was abandoned by the time the English occupied it in 1627, just as the Dutch were making their move into Brazil. Sent by a commercial syndicate in London, the English expedition to settle Barbados paused on the way to “capture a prize”—i.e., plunder another country’s vessel. They stole ten “negro slaves,” who were taken to Barbados along with the eighty settlers that disembarked on February 17, 1627.

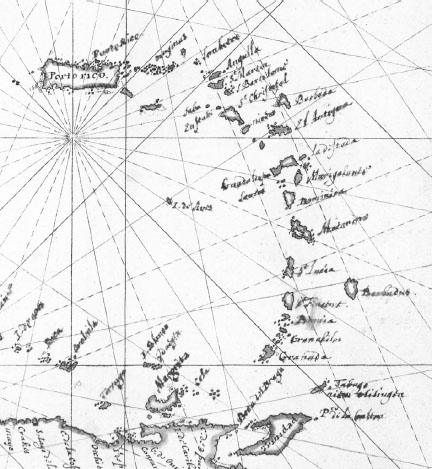

In this detail from a 1639 Dutch map by Joan Vinckeboons, Barbados is the island sticking out to the east of the arc of the Lower Antilles.

The island had no native population, but Captain Henry Powell induced thirty-two agriculturally knowledgeable native people from Dutch-held Guyana to come to Barbados, then enslaved them once they were there.4 Starvation would not be an immediate problem: the island teemed with wild hogs, the legacy of a long-gone Spanish presence. The colonists killed them off in three years flat.5

The Barbadian colonists tried raising tobacco at the same time it was being developed in Virginia and Maryland. But their product was of even poorer quality than the Chesapeake’s, and they had problems getting labor because Barbados’s checkered reputation in England made recruiting difficult. As happened over and over in the Americas, crooks and whores were sent as colonists, but they were far from satisfactory as plantation workers.

The trade balance between England and its colonies was projected to be even, via barter, without a need for settling accounts by a transatlantic flow of silver and gold that was wanted elsewhere. Since London made the rules and set the prices, London could tinker with the numbers as it liked. But just as the London planners were caught by surprise when Virginia became a tobacco exporter, they didn’t count on the Dutch setting up English colonists in Barbados in the sugar business, from a base in Brazil.

It happened in the 1640s, while England was embroiled in the civil war between Roundheads and Cavaliers. Barbados had both political tendencies present but neither controlled the society definitively, and the island was practically independent during those years, enjoying what was effectively free trade with vessels of various flags.6

The Dutch, not the English, made the Barbadians rich. Fueled by a substantial injection of Dutch capital—something strictly forbidden by London—the Barbadians learned how to make sugar, via Dutch intermediaries and also by firsthand observation from traveling to Brazil.7 The Dutch had a lot to offer the Barbadians, and they could take a profit at every step of the process. They provided the Barbadians with Europe’s cheapest credit to get started making a fortune in sugar and waited until the sugar was on the market to collect and refinance.8 They sold them the machinery and technology. They refined the molasses into sugar in Europe, and sold the sugar in the lucrative Dutch markets.

The Dutch could also provide the crucial and most expensive element: the labor. As a complement to taking Brazil, in 1637 they took the Portuguese slave castle of Elmina, offshore from the Gold Coast. They established posts on the Slave Coast (present-day Benin) that were controlled from Allada (or Ardra). For a time the Dutch controlled Luanda and Benguela in Angola as well. The strategic reason to occupy the slave ports was to support the Dutch sugar venture in Brazil, where the labor force died or escaped to the wilderness in large numbers even as acreage under cultivation was increasing. As a consequence of their move into Africa, the Dutch had plenty of slave-trading capacity with which to service the English, who were not yet engaged in the commercial African slave trade.

The Dutch didn’t rule the Brazilian northeast for long. The Brazilian planters rebelled against them in 1645, but by the time they drove the Dutch out definitively in 1654, the Barbadians had copied their techniques for making sugar and were making fortunes.9

The sugar revolution transformed Barbados. Among the skills the Barbadians learned from the Dutch and the Brazilians was the management of hundreds of slaves on a single plantation. When they converted Barbados to slave labor, they did it massively and quickly. Barbados, then, became the first place where Englishmen surrounded themselves with large numbers of enslaved Africans. The Barbadian planters had been purchasing indentures of white servants, but they made an abrupt transition to purchasing the legal rights to the bodies and the future “increase” of black laborers. They imported large numbers of kidnapped Africans, because, as with later sugar regimes, their labor force was not self-reproducing: “though we breed both Negroes, Horses, and Cattle,” wrote Richard Ligon in Barbados, “yet that increase, will not supply the moderate decays which we find in all those.”10

Along with the changeover to a slave society came accumulation by dispossession, with the mortgage as a primary tool.* The Dutch were conservative about whom they extended credit to, making for a concentration of large planters. The wealthy then extended credit to the less wealthy by means of a mortgage, and foreclosed when they could not pay, as land ownership consolidated. Many former indentured servants had been given small patches of ground at the end of their tenure; now the small farmholds of forty different farmers became the eight hundred acre property of a single sugar baron, one Captain Waterman.11

The new Barbadian sugar planters quickly developed, in Richard S. Dunn’s words, “a code of conduct that would never be tolerated at home…. In the islands there were no elders, the young were in control, and many a planter made his fortune and died by age thirty. In short, Caribbean and New England planters were polar opposites; they represented the outer limits of English social expression in the seventeenth century.”12 But these two outer limits did business with each other, as Barbados was dependent on New England for much of its food.

Barbados’s sugar revolution was well under way in 1645, when the island’s black population was 5,680. Guadeloupe and Martinique, belonging to the enemy commercial system of France, quickly followed in the conversion to sugar with the help of Dutch exiles from Brazil. On the other side of the Atlantic, some of Glasgow’s first factories were rum distilleries, which added value to the molasses Glaswegian merchants were importing from the Antilles already in the 1640s.13

As Barbados was experiencing its first rush of sugar prosperity, the execution of King Charles in 1649 sent Cavaliers fleeing to the island. They seized control of its government following a pamphlet war and armed action, making the island into a Royalist stronghold. By the following year, Barbados had declared itself for Charles II, who was in French exile. Austere, regicidal, militarized, religious extremists: the Puritan government was unpopular at home, but Barbados was in open rebellion.

More consequentially, Barbados’s practice of free trade with the Dutch antagonized the politically powerful London merchants and shippers, who were not happy about losing their captive market to foreign competition. An embargo, the Act of 1650, froze all English trade with Barbados as well as with the other Royalist colonies, including Virginia, and authorized the confiscation of all merchandise headed there. That became a hot issue in New England, whose trade with Barbados was its most profitable commercial activity.

Barbados issued what was essentially a declaration of independence on February 18, 1651, charging Parliament with placing it in a state of “slavery”—a word that would resound through pro-independence polemics on the North American mainland in the eighteenth century. Barbadian Cavaliers confiscated the lands of Barbadian Roundheads; according to an anguished letter written from Barbados, they had “Sequestred 52 Gallandt plantations, who are Werth as all ye island besydes.”14 Meanwhile, Barbadian royalists’ lands in England, Scotland, and Ireland were confiscated by Parliament.

The Puritan Parliament passed a Navigation Act in 1651 that forbade trading with foreigners, requiring the use of English ships and captains for all commerce. That quickly led to war between England and the Netherlands, leaving Barbadian planters’ Dutch business contacts on the wrong side of hostilities. Believing, perhaps not incorrectly, that Cromwell was out to destroy them, the Barbadian planters openly favored their Dutch commercial partners over their English colonial masters, effectively committing treason during wartime.

With instructions to seize Dutch merchantmen, Cromwell’s admiral Sir George Ayscue blockaded the island in 1652. Then, despite having only a small force, he attacked with the support of scurvy-ridden troops who had detoured from their mission of subduing Virginia. He bluffed the Barbadian royalists into surrendering and established a government loyal to Parliament. But the damage was done to the British colonial system: Barbados had experienced independence and free trade.15

Ayscue’s victory was only the beginning of Cromwell’s military designs. After making peace with the Dutch in 1654, he began a project—the Western Design, it was called—to drive the Spanish out of the Americas. Unfortunately, Cromwell sent an untrained, incoherent expedition of conquest to base itself in Barbados in 1655—there to provision itself, on an island dependent on importation for its food.16 Depleting the island’s scant resources, the English fleet funded itself by laying high duties on the island’s imports.

That there was already a nascent slave-breeding business of sorts in Barbados is suggested by the journal of a member of the Western Design expedition, a Puritan named Henry Whistler, who noted in 1655 that children had a cash value at birth and that there was a market in them:

This Island is inhabited with all sortes: with English, french, Duch, Scotes, Irish, Spaniards thay being Iues [Jews]; with Ingones [Indians] and miserabell Negors borne to perpetuall slavery thay and thayer seed: these Negors they doue alow as many wifes as thay will have, some will have 3 or 4, according as they find thayer bodie abell; our English heare doth think a negor child the first day it is born to be worth 511 [five pounds eleven shillings], they cost them nothing the bringing up, they goe all ways naked: some planters will have 30 more or les about 4 or 5 years ould: they sele them from one to the other as we doue shepe.17 (emphasis added)

The principle of partus sequitur ventrem was already in place. “By 1650 certainly, and probably a good bit earlier,” writes Dunn, “slavery in Barbados had become more than a lifetime condition. It extended through the slave’s children to posterity.”18 The idea that one caste of people, visibly different, could be born into bondage conflated the condition of slavery with the concept of “race.”

Before leaving Barbados on its mission of conquest, the English fleet recruited the island’s dispossessed whites to join its soldiery, a job that entailed risking one’s life but also brought the possibility of plunder, or even land. When the expedition sailed away on March 31, 1655, it took away some four thousand white Barbadians, mostly formerly indentured servants, who were never to return. In their wake were sent a rougher class: defeated Scotch and Irish soldiers captured in battle, sent as laboring prisoners, along with troublemakers, Catholics, and former landowners.

The Western Design expedition’s attack on Santo Domingo was a murderous failure, repulsed definitively by the Spanish. But then the expedition turned its sights more successfully on Jamaica. Cromwell’s navy invited pirates into Jamaica’s gaudy, raunchy, now-disappeared capital of Port Royal, beginning a golden age of piracy in the Caribbean.* While England launched attacks against Spanish coastal towns, the pirates (most infamously Henry Morgan) attacked Spanish shipping, provoking a two-fronted war that expelled the Spanish from Jamaica in 1655, though it took another five years for the English to subdue the insurgency.

This first dislodging by force of Spain from an established colony sparked a new rush for riches as politically connected merchants jockeyed for position in Jamaica. Few if any of the former Barbadian yeomen who had come to Jamaica with the fleet benefited, however; most died of disease. Some surviving soldiers received land grants and became planters, amassing large fortunes through the use of slave labor and achieving that rare, coveted condition: class mobility.

After Cromwell died in 1658, probably of a bacterial infection, the Roundheads in England deteriorated into bickering factions and the Cavaliers retook power. The extravagant, lecherous, French-raised Charles II, son of the beheaded Charles I, ascended to the English throne in 1660. Amid widespread rejoicing at the departure of the unpopular regime, the theaters of England, shuttered by the Puritans, reopened. In what has been remembered as the Restoration, London once more began to have a public life after more than a decade of Puritan sobriety, as an age of coffeehouses began.

With the Restoration came an aggressive new commercial policy designed to project an image of grandeur by maximizing the royal share of the world. Charles II was not much interested in governing, but he was attuned to the importance of the colonies; many places in the New World had been named for his father, and Maryland bore the name of his mother. In appreciation of Virginia’s loyalty, he bestowed on the colony the title of Dominion, a name that persists as Virginia’s nickname of “Old Dominion.”

Ownership of Barbadian land was quite concentrated by this time, and sugar production increased precipitously. There were twenty thousand black captives on Barbados by 1660, twenty times as many as in Virginia. By 1676, the number had grown through importation to 32,473, and 46,602 in 1684.19 The island became one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

Now that the labor force was mostly black, the situation required legal clarification. Barbados had a comprehensive slave code by 1661 that differentiated indentured servants from slaves, with provisions that were highly disadvantageous to the enslaved: killing an enslaved person was punishable only by a fine.20 The code came just in time to be useful to Jamaican lawmakers; Charles II formally annexed Jamaica for England in 1661.

Parliament passed another Navigation Act in 1660, requiring exclusivity of trade by the colonies, who could conduct commerce only with English ships that were captained by Englishmen and three-fourths of whose sailors were English. Subsequent Navigation Acts were passed in 1662 and 1663 and were followed up in 1673 and 1696, defining a policy that would in one form or another endure through the Napoleonic era. The Navigation Acts were highly consequential; by denying the Dutch access to American markets controlled by England, they consolidated England’s position as the number-one commercial power.

They also empowered the New England colonists, though that was an unintended consequence. New England had been conducting some hemispheric trade since the 1630s. Now, since colonial ships counted as English, the Navigation Acts stimulated the New England shipping industry, turning the New Englanders into “the Dutch of England’s empire.”21 New England’s territorial advancement to the north was blocked by French Canada. Especially in the case of the Rhode Island colony, founded in 1636 by Massachusetts dissident Roger Williams, New England had little in the way of a hinterland. Rhode Island was like Portugal in that both places consisted mostly of coastline; like the Portuguese, Rhode Islanders turned to the sea to make money.

The colonists weren’t allowed to manufacture, but New England ships could run down to the West Indies and exchange their farm and fishing products for molasses, which they brought home and distilled into great quantities of rum. The New Englanders also sold the Barbadians kidnapped Native Americans as slaves, but since New England was hemmed in by French Canada, their supply was limited.

Charles II was more interested in trying to find gold than slaves when he chartered the Governor and Company of the Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa on January 10, 1662.22 Most of Africa had no gold, but the Gold Coast had for centuries provided a money supply to the Muslim world. Its gold, traded overland up through the Maghreb and into Europe, had been turning up in English commerce since at least the thirteenth century, when the Royal Mint was established. Though the Gold Coast’s resources were partly depleted by the time of the Restoration, it was still a gold producer.

At that time, the Gold Coast was not an exporter of African slaves, but an importer: an intra-African coastal slave trade conducted by Portuguese captains brought laborers kidnapped from Calabar to labor in the Akans’ gold works.23 Under pressure from the colonies to supply labor, English traders began to insist on taking slaves from the Gold Coast as well as gold and ivory. The company instructed its traders not to pay for slaves with gold but with barter, because the idea was to bring gold home. But African traders quickly began demanding gold for at least part of the price of slaves, the rest being made up of manufactured goods.

The Royal Mint began striking a new gold piece in 1663, the first machine-minted English coin, intended to be worth twenty shillings (actual exchange rates were different). A tiny elephant embossed on each one—sometimes an elephant and castle—let the world know that England’s money was made with Africa’s gold. The coins became known almost immediately as “guineas,” from the name of the long coastal stretch of West Africa between the mountain ranges of Sierra Leone and the Bight of Biafra. Elephant and elephant-and-castle guineas were minted until 1726, though later non-African-themed guineas were minted until 1813, the monarch pictured on the “heads” side changing with the throne.

Detail of a guinea.

The castle was a direct image of England’s growing importance in the slave trade, while the coin’s elephant image depicted another of the sources of wealth of the African trade: ivory, used in all manner of fine manufactures, notably including musical instruments. Ivory comes from killing a male animal (only the males have big tusks) of five tons or so in order to harvest the approximately 1 percent of its body weight that is dentine mass, while leaving the carcass for carrion eaters. As keyboards appeared all over Europe and America, the intelligent animals were slaughtered in large numbers so their teeth could produce ivory for the fingers of well-bred young ladies to caress, the market picking up when the piano began to be mass-produced in the nineteenth century. Ivory toothpicks became a necessary gentleman’s item in Europe. In Africa, where hunting elephants was basic to survival and hunting lore was remembered in the form of song, the animal was consumed after slaughter and the tusks used as ceremonial trumpets across a wide range of the continent.

England’s creation of the guinea spearheaded an offensive in which it squared off against the Netherlands. Charles II’s brother James (the future King James II), who bore the king’s brother’s traditional title of Duke of York, prosecuted a second Anglo-Dutch war, fought on multiple fronts in different parts of the world. The English attacked Dutch slave-trading positions on the African coast, and in 1664, they took control of Nieuw Amsterdam, renaming it New York in honor of the city’s new royal master. But they were otherwise badly beaten in the war, which ended in 1667 with England’s humiliating defeat. In the treaty negotiations, the English offered to trade New York back to the Dutch in exchange for the sugar-producing, moneymaking South American colony of Surinam, but the Dutch refused the offer. The English kept Manhattan, locking in their control of the Atlantic seaboard from New England down to Virginia.

That stretch of the North American Atlantic coast formerly claimed by the Dutch became property of the Duke of York, James Stuart; Charles II gave him all the land between New England and Maryland. James in turn dealt out the territory between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers to John Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, never mind that people already lived there. It was divided into East Jersey and West Jersey, with the whole collectively known as, according to the document signed by James, “New Caeserea or New Jersey,” whose birth was thus pure cronyism.24 Up the Hudson, the Dutch Fort Nassau was renamed Albany, for James’s Scottish title. Located on the Mohawk River, in the gap between the Catskills and the Adirondack Mountains, Albany was perfectly positioned for commerce with the West.

The Anglo-Dutch war badly damaged the ineffective Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa, which was reorganized and renamed the Royal African Company in 1672. But the new company was also badly managed, and it made no attempt to get North American slaveowners the labor they wanted. The gap was filled by independent entrepreneurs.

As soon as there were slaves, there were conspiracies to rebel—sometimes involving indentured whites as well, sometimes together with Native Americans. Herbert Aptheker lists the first “serious conspiracy involving Negro slaves” in English North America as occurring in Virginia in 1663, when there were still relatively few black people in Virginia and they had only just been declared to be slaves.25 The Virginia Assembly, in passing a 1672 act that authorized the killing of maroons, with reparations made at public expense to the individual slaveowners thus deprived of property, noted, “it hath beene manifested to this grand assembly that many negroes have lately beene, and now are out in rebellion in sundry parts of this country and that noe meanes have yet beene found for the apprehension and suppression of them from whome many mischeifes of very dangerous consequence may arise to the country if either other negroes, Indians or servants should happen to fly forth and joyne with them.”26 A similar authorization was passed in 1680, suggesting that the problem continued to vex the Virginians.

A plot to murder the masters, neither the first nor the last, was discovered on Barbados in 1674. Whether it existed in reality or not is hard to say, since slave societies were particularly alert to potential uprisings, to the point of sometimes executing people for imagined crimes. According to a pamphlet published in London in 1676, the conspiracy was led by the “Cormantee”—Akan people from the Gold Coast. The pamphlet’s text is notable for its description—complete with, supposedly, elephant-tusk trumpets—of the artistry and artisanship attendant to Gold Coast royal pageantry, of which some seventeenth-century Barbadians would have had firsthand knowledge from slaving voyages. It also includes an early occurrence of the word Baccararoe, i.e., buckra, which would become a black term for whites throughout the English-speaking Americas:

This Conspiracy first broke out and was hatched by the Cormantee or Gold-Cost Negro’s about Three years since, and afterwards Cuningly and Clandestinely carried, and kept secret, even from the knowledge of their own Wifes.

Their grand design was to choose them a King, one Coffee an Ancient Gold-Cost Negro, who should have been Crowned the 12th of June last past in a Chair of State exquisitely wrought and Carved after their Mode; with Bowes and Arrowes to be likewise carried in State before his Majesty their intended King: Trumpets to be made of Elephants Teeth and Gourdes to be sounded on several Hills, to give Notice of their general Rising, with a full intention to fire the Sugar-Canes, and so run in and Cut their Masters the Planters Throats in their respective Plantations where-unto they did belong.

Some affirm, they intended to spare the lives of the Fairest and Handsomest Women (their Mistresses and their Daughters) to be Converted to their own use. But some others affirm the contrary; and I am induced to believe they intended to Murther all the White People there, as well Men as Women: for Anna a house Negro Woman belonging to Justice Hall, overhearing a Young Cormantee Negro about 18 years of age, and also belonging to Justice Hall, as he was working near the Garden, and discoursing with another Cormantee Negro working with him, told him boldly and plainly, He would have no hand in killing the Baccaroroes or White Folks; And that he would tell his Master.

All which the aforesaid Negro Woman (being then accidentally in the garden) over-heard, and called to him the aforesaid Young Negro Man over the Pales, and enquired and asked of him What it was they so earnestly were talking about? He answered and told her freely, That it was a general Design amongst them the Cormantee Negro’s, to kill all the Baccararoes or White People in the Island within a fortnight. Which she no sooner understood, but went immediately to her Master and Mistris, and discovered the whole truth of what she heard, saying withal, That it was great Pity so good people as her Master and Mistriss were, should be destroyed.27

This account exemplifies what was already a well-worn conspiracy theory, combining as it does three major tropes of white narratives of slave rebellion:

1) decisions taken by a council of slaves from various plantations to stage an organized rebellion (as would in fact happen more than a century later in Saint-Domingue/Haiti);

2) the assertion by the chronicler of the intention of the black rebels to kill white men and take white women for sexual use; and

3) the salvation of the whites by the intercession of a faithful domestic slave who betrays the conspiracy of the black rank-and-file out of love for her master’s family.

These elements recur in masters’ accounts of conspiracies throughout the hemispheric history of slavery, both black and indigenous. The following excerpt from the same pamphlet concludes with the characteristic final trope of the slave rebellion narrative, portrayed as a happy ending: the torture and massacre by the masters of a number of the enslaved. It also reports a common belief of Africans, reported in various parts of the Americas, that the enslaved would return to Africa upon death.

Six burnt alive, and Eleven beheaded, their dead bodies being dragged through the Streets, at Spikes a pleasant Port-Town in that Island, and were afterwards burnt with those that were burned alive…

The spectators … cryed out to Tony, Sirrah, we shall see you fry bravely by and by. Who answered undauntedly, If you Roast me to day, you cannot Roast me tomorrow: (all those Negro’s having an opinion that after their death they go into their own Countrey). Five and Twenty more have been since Executed.28

In this telling from a colonist, the death of Africans was only of importance as the cost of doing business.

*The term “accumulation by dispossession” was suggested by David Harvey, who proposes it as an update to Marx’s “primitive accumulation.” Harvey, 137.

*Port Royal was permanently submerged by earthquake and tsunami in 1692.