16

16 16

16As the staples of Carolina were valuable, and in much demand, credit was extended to that province almost without limitation, and vast multitudes of negroes, and goods of all kinds, were yearly sent to it. In proportion as the merchants of Charlestown received credit from England, they were enabled to extend it to the planters in the country, who purchased slaves with great eagerness, and enlarged their culture.1

If We allow Slaves we act against the very Principles by which we associated together, which was to relieve the distressed. Whereas, Now we Should occasion the misery of thousands in Africa, by Setting Men upon using Arts to buy and bring into perpetual Slavery the poor people who now live free there.2

LONDON NEWSPAPERS HAILED THE initiative to found Georgia. It was the product of humanistic and philanthropic movements in London, and also of public relations. The colony’s visionary founder, James Oglethorpe, spent two years directing the colony’s promotional campaign before sailing for America.3

Oglethorpe was an aristocrat formerly allied with the Stuarts. He had studied classical antiquity at Oxford’s Corpus Christi College, then went to military school in Paris and fought against the Turks in the 1717 siege of Belgrade.4 Becoming radicalized after his scholar friend Robert Castell died in debtor’s prison, Oglethorpe wanted to help the poor better themselves in the autocratic, militarized utopia he would build.5 Georgia was intended to be a site of relief where debtors could have a fresh start—though in practice, no debtors were among the colonists—while functioning as the avant-garde of England’s North American empire, protecting South Carolina from Florida.

Drawing on his studies of Greece and Rome, Oglethorpe devised a unique plan for a city: a matrix of connected rectangular plazas—twenty-four were built—each one serving as a commons around which were to be housed ten families, with garden plots for subsistence located within walking distance. Because of that plan, and with help from the lush vegetation, historic Savannah today is one of the most beautiful urban environments in the United States.

The colonists carved out their plots from a densely wooded area on a bluff overlooking the Savannah River, beginning the construction of Oglethorpe’s meticulously planned community of 240 freeholders. He also founded several other communities in Georgia: Darien; Frederica; James Brown’s future home town of Augusta, on the South Carolina border; and Ebenezer, a community of persecuted Protestants from Salzburg who were dead set against slavery. A group of forty-one Jews, all but seven of them Sephardic Portuguese, arrived on July 11, 1733, and founded a short-lived congregation in 1735. After checking with lawyers in Charles Town as to whether Jews could be admitted to Georgia, Oglethorpe was advised that they could be, since they weren’t papists. Their arrival upset the trustees in London, but they were powerless to do anything about it.6

Oglethorpe, who had been deputy-governor of the Royal African Company, saw slavery as a bad system that would lead to problems in Georgia—and not only because the ever-present potential for rebellion was aggravated by San Agustín’s offer of freedom directly to the south. He also saw it as a corrupting influence on white colonists. Oglethorpe felt the same way about rum, prohibiting its sale, though wine and beer were permitted. Nor did he want a real estate market; in Oglethorpe’s Georgia, land given to colonists was passed on by entail: it could not be sold, only inherited, and only by men.

As the first houses of Savannah were being built and moved into, Oglethorpe lived in a tent to set an example of self-sacrifice for the others. But there was trouble from the beginning, and in an isolated community riven by vicious personal rivalries and much disagreement, slavery was a divisive issue.

Charles Town did more to destroy Oglethorpe’s utopia than Florida. Carolina merchants ran trade routes all through the area, and Savannah was dependent on them for many kinds of supplies. But Oglethorpe didn’t want his colony buying the supplies the Carolinians most wanted to sell: slaves. Moreover, Georgia’s resistance to rum impeded the Carolinians’ business of selling it to the Native Americans along with the guns and ammunition they were selling them, which created friction.7

As slaveowners would do more than a century later in Missouri and Kansas—and would even attempt to do in Southern California—the South Carolinians infiltrated pro-slavery colonists into Georgia. The Carolinians who moved down into Georgia had no more respect for Oglethorpe’s restrictions than they previously had for the lords proprietors’. From South Carolina, Eliza Lucas Pinckney complained in a September 1741 letter of Oglethorpe’s “Tyrannical Government in Georgia,” presumably because its residents were denied the freedom to own slaves, plant large plantations with staple monocrops, deal in rum, or buy and sell land.8 Noting ill treatment of indentured servants in Savannah that had caused some to desert, colonist Thomas Jones wrote: “The Carolina Temper, of procuring Slaves, and treating them with Barbarity, seems to be very prevalent among us.”9

Charles Town merchants thus began making money importing Africans from British slave traders for re-export into Georgia, a market that would keep them rich for generations. Prosperity reigned; in 1732, the year Georgia was planted, Benjamin Franklin’s ex-apprentice Lewis Timothy founded the South Carolina Gazette, with Franklin as a silent partner. The South’s second newspaper to appear, it was as strategic a media rollout as the times afforded: South Carolina’s economy, heavily centralized in Charles Town, was booming. By 1735 Charles Town was sufficiently wealthy and cultured to found the St. Cecilia concert society. Its fast-growing wealthy elite consumed luxury goods. It was the prime underserved advertising market.

Meanwhile, another migration to North America was picking up: the so-called Scotch-Irish, whose Presbyterianism made them a dissenting sect in Anglican Ulster. They had to settle to the west, because the good coastal land was taken. After the first such colony moved to South Carolina to receive land grants near the Santee River, establishing Williamsburg in 1732, they were in “low and miserable circumstances,” wrote Alexander Hewatt, until they too bought slaves from the Charles Town merchants and their lands “in process of time became moderate and fruitful estates.”10

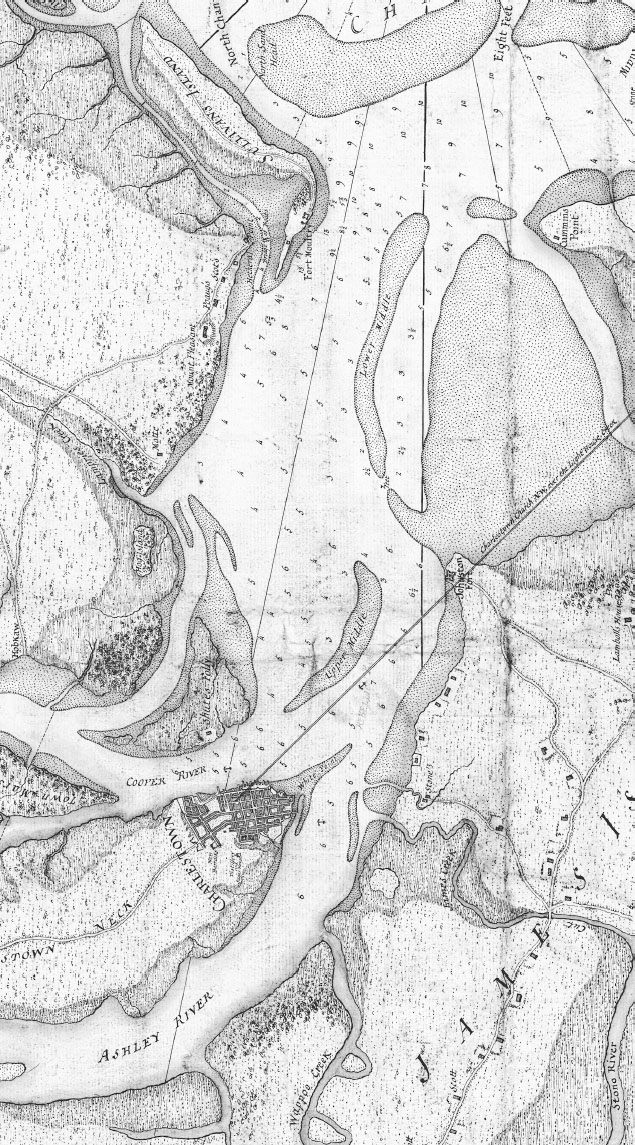

A view of Charles Town, as depicted in 1739 by artist Bishop Roberts and etcher W. H. Toms, emphasizes the constant activity in its port.

The border was still dangerous. Having Georgia as a buffer between South Carolina and Florida made Carolina that much more secure. But England and Spain were still facing off in the region; the Spanish responded by inducing more of the English colonists’ slaves to escape.

There were already small communities of free blacks around San Agustín, but in October 1733 a Spanish edict reiterated that people reaching Florida and accepting the Catholic faith would be free, increasing the flow of runaways. To further bedevil the Carolinians, a free black garrison town, called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, was established in 1738 about two miles north of San Agustín, providing a first line of defense for the Spanish.* Its governor was Francisco Menéndez, the leader of Florida’s black militia. A Mandinga who was born a Muslim, Menéndez had been kidnapped to Barbados as a boy and then taken to South Carolina. He defected to the Yamasee Indians at the time of the Yamasee War in 1715 and ultimately escaped to Florida, where he accepted Catholicism and was baptized with his Spanish name.11 There was a price on his head in South Carolina, but no matter: he was fighting for the Spanish, and he had weapons. The news traveled: a free black town on the side of the Spanish, with Bakongo soldiers among its residents, within marching distance.

In 1738, the Spanish at San Agustín announced that runaways would be given freedom and land, sweetening the attraction the Florida territory already had for Carolina slaves. Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, with its good contacts in South Carolina, ran the following item on October 8, 1739:

Extract of a Letter from Charlestown in South Carolina.

The Spaniards of St. Augustine near Georgia, have issued a Proclamation, giving Freedom to all white Servants and Negro or Indian Slaves, belonging to Carolina, Parrisburg or Georgia, that will go over to them, and have allotted them Land near St. Augustine, where upwards of 700 have been receiv’d to the great Loss of the Planters of those Parts, which will prove their Ruin if a Stop is not put to such a villanous Proceeding. This is a certain Proof of their Intent to attack Georgia, in which Case these Servants and Slaves are to be their Pilots and our worst Enemies.

The feared uprising had already happened but word of it hadn’t reached Philadelphia yet. Remembered as the Stono Rebellion, it erupted about twenty miles from Charles Town on September 9, 1739. The anonymous sole firsthand description of the event is not too long to reproduce in its entirety.

AN ACCOUNT OF THE NEGROE INSURRECTION IN SOUTH CAROLINA

Sometime since there was a Proclamation published at Augustine, in which the King of Spain (then at Peace with Great Britain) promised Protection and Freedom to all Negroes Slaves that would resort thither. Certain Negroes belonging to Captain Davis escaped to Augustine, and were received there. They were demanded by General Oglethorpe who sent Lieutenant Demere to Augustine and the Governour assured the General of his sincere Friendship, but at the same time showed his Orders from the Court of Spain, by which he was to receive all Run away Negroes.

Of this other Negroes having notice, as it is believed, from the Spanish Emissaries, four or five who were Cattle-Hunters, and knew the Woods, some of whom belonged to Captain Macpherson, ran away with His Horses, wounded his Son and killed another Man. These marched f [sic] for Georgia and were pursued, but the Rangers being then newly reduced [sic] the Countrey people could not overtake them, though they were discovered by the Saltzburghers, as they passed by Ebenezer. They reached Augustine, one only being killed and another wounded by the Indians in their flight. They were received there with great honours, one of them had a Commission given to him, and a Coat faced with Velvet.

Amongst the Negroe Slaves there are a people brought from the Kingdom of Angola in Africa, many of these speak Portugueze [which Language is as near Spanish as Scotch is to English,] by reason that the Portugueze have considerable Settlement, and the Jesuits have a Mission and School in that Kingdom and many Thousands of the Negroes there profess the Roman Catholic Religion. Several Spaniards upon diverse Pretences have for some time past been strolling about Carolina, two of them, who will give no account of themselves have been taken up and committed to Jayl in Georgia.

The good reception of the Negroes at Augustine was spread about, Several attempted to escape to the Spaniards, & were taken, one of them was hanged at Charles Town. In the later end of July last Don Pedro, Colonel of the Spanish Horse, went in a Launch to Charles Town under pretence of [taking] a message to General Oglethorpe and the Lieutenant Governour.

On the 9th day of September last being Sunday which is the day the Planters allow them to work for themselves, Some Angola Negroes assembled, to the number of Twenty; and one who was called Jemmy was their Captain, they suprized a Warehouse belonging to Mr. Hutchenson at a place called Stonehow [Stono]; they there killed Mr. Robert Bathurst, and Mr. Gibbs, plundered the House and took a pretty many small Arms and Powder, which were there for Sale. Next they plundered and burnt Mr. Godfrey’s house, and killed him, his Daughter and Son. They then turned back and marched Southward along Pons Pons, which is the Road through Georgia to Augustine, they passed Mr. Wallace’s Ta[v]ern towards day break, and said they would not hurt him for he was a good Man and kind to his slaves, but they broke open and plundered Mr. Lemy’s House, and killed him, his wife and Child. They marched on towards Mr. Rose’s resolving to kill him; but he was saved by a Negroe, who having hid him went out and pacified the others.

Several Negroes joined them, they calling out Liberty, marched on with Colours displayed, and two Drums beating, pursuing all the white people they met with, and killing Man Woman and Child when they could come up to them. Collonel Bull Lieutenant Governour of South Carolina, who was then riding along the Road, discovered them, was pursued, and with much difficulty escaped & raised the Countrey. They burnt Colonel Hext’s house and killed his Overseer and his Wife. They then burnt Mr. Sprye’s house, then Mr. Sacheverell’s, and then Mr. Nash’s house, all lying upon the Pons Pons Road, and killed all the white People they found in them. Mr. Bullock got off, but they burnt his House, by this time many of them were drunk with the Rum they had taken in the Houses.

They increased every minute by new Negroes coming to them, so that they were above Sixty, some say a hundred, on which they halted in a field, and set to dancing, Singing and beating Drums, to draw more Negroes to them, thinking they were now victorious over the whole Province, having marched ten miles & burnt all before them without Opposition, but the Militia being raised, the Planters with great briskness pursued them and when they came up, dismounting; charged them on foot. The Negroes were soon routed, though they behaved boldly several being killed on the Spot, many ran back to their Plantations thinking they had not been missed, but they were there then taken and Shot, Such as were taken in the field also, were after being examined, shot on the Spot, And this is to be said to honour of the Carolina Planters, that notwithstanding the Provocation they had received from so many Murders, they did not torture one Negroe, but only put them to an easy death.

All that proved to be forced & were not concerned in the Murders & Burnings were pardoned, And this sudden Courage in the field, & the Humanity afterwards hath had so good an Effect that there hath been no farther Attempt, and the very Spirit of Revolt seems over. About 30 escaped from the fight, of which ten marched about 30 miles Southward, and being overtaken by the Planters on horseback, fought stoutly for some time and were all killed on the Spot. The rest are yet untaken. In the whole action about 40 negroes and 20 whites were killed.

The Lieutenant Governour sent an account of this to General Oglethorpe, who met the advices on his return from the Indian Nation[.] He immediately ordered a Troop of Rangers to be ranged, to patrole though Georgia, placed some Men in the Garrison at Palichocolas, which was before abandoned, and near which the Negroes formerly passed, being the only place where Horses can come to swim over the River Savannah for near 100 miles, ordered out the Indians in pursuit and a Detachment of the Garrison at Port Royal to assist the Planters on any Occasion, and published a Proclamation ordering all the Constables &c. of Georgia to pursue and seize all Negroes, with a Reward for any that could be taken. It is hoped these measures will prevent any Negroes from getting down to the Spaniards.12

A brief account of this uprising in the Pennsylvania Gazette on November 8 read:

We hear from Charlestown in South-Carolina, that a Body of Angola Negroes rose upon the Country lately, plunder’d a Store at Stono of a Quantity of Arms and Ammunition, and murder’d 21 white People, Men, Women and Children before they were suppress’d: That 47 of the Rebels were executed, some gibbeted and the Heads of others fix’d on Poles in different Parts, for a Terror to the rest.

John Thornton underscores the probable military background of the “Angola Negroes.” They were likely not Kimbundu-speaking Angolans, relatively few of whom came to North America, but their immediate neighbors to the north, who were Bakongo. The term “Angola,” Thornton writes, “surely meant the general stretch of Africa known to English shippers as the Angola coast,” though the possibility exists that some people from various central African origins were mixed in.13 In a world divided by religion, that these Africans were Catholic made them instant allies of the Spanish.

As the slave trade created business opportunities in Africa, African despots formed regularly organized armies and battled each other, the losers being sold into slavery. The result was that the ranks of the enslaved in the Americas included increasing numbers of combat-seasoned veterans of gun-toting African armies. In her history of Kongo Catholicism, Cécile Fromont identifies the ceremony that preceded the Stono uprising as “a typical central African sangamento, a martial performance in preparation for battle, in a manner similar to that used by contemporary Kongo armies.”14 The mention of drums and singing ties the Stono rebellion in with later rebellions as well as with Kongo military and spiritual influence, in Saint-Domingue and Cuba. African drums were a means of military communication, as the British well understood. Since 1699 the law in Barbados had stipulated that

Whatsoever Master, &c., shall suffer his Negro or Slave at any time to beat Drums, blow Horns, or use any other loud instruments, or shall not cause his Negro-Houses once a week to be search’d, and if any such things be there found, to be burnt … he shall forfeit 40 s. Sterling.15

The South Carolina Gazette ran no articles about the Stono uprising, apparently fearing even to mention the subject where the black majority might learn of it. But a Charles Town merchant wrote in a letter of December 27 of that year, “We shall Live very Uneasie with our Negroes, while the Spaniards continue to keep Possession of St. Augustine.”16 “For several years after [Stono],” writes Peter H. Wood, “the safety of the white minority, and the viability of their entire plantation system, hung in serious doubt.”17

Believing foreign slaves to be the most dangerous, South Carolina raised the duty on slave importation from £10 to a prohibitive £50. But that made for considerable lost income for local government in a territory where slaves had accounted for two-thirds of customs revenues in 1731, so in 1744 the duty was lowered back to its previous level. Previously, South Carolina had imposed double duties on slaves not coming from Africa, apparently in order to discourage the unloading of incorrigible West Indian slaves into their territory.18

The author of an 1825 pro-slavery pamphlet in Charles Town noted that the Stono rebellion was also remembered as the Gullah War.*19 In recent years, Y. N. Kly has been arguing for the use of the term “Gullah War” as a blanket name for the ongoing black resistance struggle in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida that lasted from Stono until 1858, with the end of what is usually called the Third Seminole War.20 This Gullah War can be seen as part of the larger war against slavery, fought in ways large and small by the enslaved. From this perspective, slave rebellions reveal themselves not to be isolated struggles, as they have been frequently characterized, but rather as eruptions of a widespread, ongoing state of resistance. Their tactics ranged from day-to-day resistance, to absconding, to full-out uprising, to actions taken by the enslaved in major wars.21

In the wake of Stono, the South Carolina legislature on May 10, 1740, passed a detailed new slave code. “An act for the better ordering and governing Negroes and other slaves in this province,” or, more simply, the Negro Act, had long been in preparation but some had thought it severe; its passage was catalyzed by the crisis atmosphere. Under its regulations, teaching a slave to write† became punishable by a fine of one hundred pounds; masters had to apply to the legislature for permission to manumit; and it even forbade slaveowners to allow their slaves to dress in “clothes much above the condition of slaves.”

Aimed at making impossible the kinds of public assemblies that could turn into mobs or hatch conspiracies, Article 36 (out of 58) paraphrased the existing Barbadian regulation to stipulate that “whatsoever master, owner or overseer shall permit or suffer his or their Negro or other slave or slaves, at any time hereafter, to beat drums, blow horns, or use any other loud instruments or whosoever shall suffer and countenance any public meeting or feastings of strange Negroes or slaves in their plantations, shall forfeit ten pounds, current money, for every such offence.” One long-term consequence of this and similar legislation was that African hand drums, so rigorously prohibited by the British colonists, do not turn up in popular African American music until they came into the United States via the Cubans in the mid-twentieth century. That African drums were played on some Southern plantations is documented, but they do not seem to have flourished outside their immediate context.

Another clause of the Negro Act forbade slaves from engaging in sales, and yet another restricted gatherings of “great Numbers of Negroes, both in Town and Country, at their Burials and on the Sabbath Day.” All this was in marked contradistinction to New Orleans, where Sunday gatherings were already taking place at the commons later known as Congo Square.

The Negro Act was not discussed in the South Carolina Gazette. Days after the legislature adjourned, a slave conspiracy was uncovered (or perhaps imagined) in June 1740 among plantation slaves planning to strike in some numbers against Charles Town. The undoing of that conspiracy—also unreported in the Gazette, though other colonial newspapers took up the slack—resulted in the hanging of fifty people, in daily batches of ten. The following year, after a purportedly murderous slave conspiracy was uncovered in New York, the second largest black city after Charles Town, magistrate Daniel Horsmanden executed or exiled over one hundred people. Horsmanden, who may have dramatically exaggerated an existing plot or may have even imagined it all, linked the never-realized black insurrection to an alleged Catholic plot involving the Spanish.22 Between 1730 and 1760 there were twenty-nine slave revolts reported in North America, about one a year, with an unknown number of others of smaller dimensions going unreported.23

When a calamitous fire in Charles Town on November 18, 1740, “in a very short time laid the fairest and richest part of the town in ashes, and consum’d the most valuable effects of the merchants and inhabitants,” it was said at first that the fire had been set by slaves, though this apparently was not true.24 The clergyman Josiah Smith preached a sermon, subsequently published with the title “The Burning of Sodom,” that spoke of the fire as God’s punishment for wickedness. Smith excoriated the whites of the town for defiling themselves by having sex with their slaves—not because they were taking unfair advantage of their captives but because they were cohabiting with inferiors. Reverend Smith insisted there was a great deal of fornication going on:

there has been too much Affinity in our Sins and those of Sodom, as there has been in our Punishment.—Whether we have any Sodomites in our Town strictly so, I can’t say.—Such abandon’d Wretches generally curse the Sun, and hate the Light, lest their Deeds should be reproved.—But in some Respects and Instances we declare our Sin as Sodom; we hide it not—We have proclaim’d on the House-Top what we should be asham’d of in Secret … Let us enquire seriously, Whether our Filthiness be not found in our Skirts?—Whether our Streets, Lanes and Houses, did not burn with Lust, before they were consumed with Fire? … That unnatural Practice of some Debauchees, that Mixture and Production, doubly spurious, of WHITE AND BLACK; and taking those to our Bed and Arms, whom at another Time we set with the Dogs of our Flock, ought to stand in red Capitals, among our crying Abominations! I know not, if Sodom had done this!25

The news of Stono arrived in Georgia concurrently with the confirmation that, as rumored, England and Spain were at war yet again. It was especially unhappy news because tensions along the disputed Georgia-Florida border had been the catalyst for the hostilities.

Britain’s enduring, disingenuous name for the resulting war was applied to it much after the fact, in 1858, by Thomas Carlyle: the War of Jenkins’ Ear. This referred to an incident that occurred off the coast of Florida in 1731, eight years before the war began. A Spanish coast guard patrol boat from San Agustín boarded a British brig, during which action the Spanish officer Juan de León Fandiño cut off the ear of the British captain Thomas Jenkins, taking in vain the name of the British king as he did so; the pickled ear was subsequently exhibited on the floor of Parliament.

Remembering the conflict as the War of Jenkins’ Ear might suggest that the war was somehow trivial or silly. In Spain, however, the war was remembered not by that anecdotal incident but by its underlying financial cause: the Guerra del Asiento. British merchants commonly used their slave shipments to the Spanish colonies as trojan horses to smuggle in all sorts of other prohibited goods. Worse, the British government had stopped making its payments for the asiento to Spain as called for.

With England and Spain at war, Oglethorpe led a monthlong siege of San Agustín in 1740 but failed to take it; its defenders included about a hundred black militiamen from Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, led by Yamasee War veteran Francisco Menéndez.26 Meanwhile, a dissident faction in Georgia, dubbed the Malcontents, were uninterested in small, self-sufficient, inalienable farms. They wanted to get rich via large, debt-driven, plantation slavery, and they wanted a functioning real-estate market so that they could buy out or seize the farms of others. Oglethorpe thought them in league both with the Charles Town merchants (which they were) and the enemy in San Agustín (perhaps not). Oglethorpe wrote the trustees on May 28, 1742:

The Mutinous Temper at Savannah now shows it self to be fomented by the Spaniards, & that the Distruction of that Place was but part of their Scheme for raising a general Disturbance through all North America…. They found three Insuperable obstacles in their way in driving out the English from this Colony. 1st. The People being white & Protestants & no Negroes were naturally attached to the Government. 2dly. The Lands being of Inheritance, as Men could not Sell, they would not leave the Country so easily, as new commers would do, who could Sell their Emprovements. 3d. Distilled Liquors were prohibited which made the Place Healthy.

Their Partizans laboured to get those who Perhaps intended no ill to bring about what they Desired. 1st. To Obtain Negroes being secure that Slaves would be either Recruits to an Enemy or Plunder for them. 2dly. Land Alianable which would bring in the Stock Jobbing Temper, the Devill take the Hindmost. 3d. Free Importation of Rum & Spirits which would Destroy the Troops & Laboring People here.27 (paragraphing added)

The war with Spain made Savannah’s Jewish community particularly nervous, since they had fled the Inquisition. The community collapsed in 1741, and some of its members relocated to Charles Town where a congregation was organized in 1749, with the community divided between “Portuguese” (Sephardic) and “German” (Ashkenazi).28

Oglethorpe defeated a Spanish invasion of St. Simons Island in the descriptively named Battle of Bloody Marsh on July 6, 1742, effectively consolidating Britain’s ownership of the Spanish-claimed territory of Georgia. The force that attacked St. Simons Island was a large one: about a thousand Spanish regulars and five hundred or so black militiamen from Cuba, where a quarter or more of the soldiery was pardo (mulatto) or moreno (black). Alexander Hewatt, a Scottish Presbyterian minister who wrote the first history of South Carolina and Georgia (after being expelled from Charles Town as a Loyalist in 1777), recalled the frightening impression made by the presence of uniformed black soldiers:

Among their land forces they had a fine company of artillery, under the command of Don Antonio de Rodondo, and a regiment of negroes. The negro commanders were clothed in lace, bore the same rank with white officers, and with equal freedom and familiarity walked and conversed with their commander and chief. Such an example might justly have alarmed Carolina. For should the enemy penetrate into that province, where there were such numbers of negroes, they would soon have acquired such a force, as must have rendered all opposition fruitless and ineffectual.29

The war was mostly over by 1742, after an attempted occupation of Cartagena by some thirty thousand British troops was repulsed, though hostilities continued through 1748. During the war, Spanish ships (joined in 1741 by French ones) preyed on shipments bringing American tobacco to London, denying the Chesapeake’s tobacco farmers access to their market in Britain. This further encouraged the farmers in their ongoing switch to wheat, which had a domestic market, took fewer weeks of labor than tobacco, and needed less tending as it grew.30

Meanwhile, the British were cut off from their supply of indigo in the French West Indies, spurring the development of indigo production in South Carolina.

The first crop of indigo was brought in 1744 about five miles from the site of the Stono Rebellion by the twenty-one-year-old Eliza Lucas. A true godmother of American slavery, Lucas had lived most of her life in Antigua, where her father was the lieutenant governor. After trying her hand at raising ginger, alfalfa, cotton, and cassava at her father’s South Carolina plantations, which she managed in his absence, she found she could grow indigo with seeds of the West Indian variety that her father sent her—but she could not process the plant into dye until her father sent her a “negro man” who knew how.31 After the success of her crop, she distributed seed to her neighbors and married Charles Pinckney of Charles Town, becoming Eliza Lucas Pinckney.

Britain paid a bounty for indigo cultivation in order to have a supply of dye for its growing textile manufactures, though the South Carolina product was inferior in quality to the indigo they had been receiving from India. Indigo was the perfect complement to rice. Both called for large amounts of labor and, most importantly, they grew in different seasons, allowing for one overworked labor force to produce two different staple crops in a year. Both crops required disagreeable, unhealthy work.

Accounts of indigo production describe the terrible stench it gave off as the plants decomposed after infusion. It attracted grasshoppers and clouds of flies, was toxic to the workers, depleted the soil, and ruined the surrounding land for cattle, which were needed to provid basic nourishment for the region. But once processed, it was a perfect long-distance export: a small amount of the concentrated, solid dyestuff had a high value. It was even more profitable than rice. The success of indigo made South Carolina much more profitable, further stimulating British trade, most especially the slave trade, to the colony.

Charles Town, at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, at the end of a defensible channel behind barrier islands, as depicted in a 1780 map by William Faden. Sullivan’s Island, to the right, was the entry and quarantine point for upwards of a hundred thousand Africans.

Oglethorpe returned to England for good in 1743, leaving behind William Stephens as governor. Stephens followed Oglethorpe’s principles—at tremendous personal cost, since his son Thomas had become a leader of the Malcontents—but in 1749 he admitted defeat, advising the trustees that the prohibition against slavery was no longer enforceable. Slavery was legalized in Georgia as of January 1, 1751, and by 1752 the trustees had washed their hands of the place as the territory reverted to crown colony status. The itinerant traders who brought slaves in from South Carolina became known by a name that would outlive them: Georgiamen.

Twenty years after its founding as the first free-soil territory in the nascent British Empire, Georgia was firmly established as a satellite of South Carolina’s world of plantation slavery. Though slaveowners frequently accused Britain of having forced the system of slavery on them, the case of Georgia offered an unambiguous model to the contrary: the British who established the colony wanted no slavery, but some of the colonists—and the South Carolina merchants—did.

*The site of Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose was found in a 1986 architectural dig and is now a Florida state park.

*The name of the creolized African American people called “Gullah” in South Carolina likely derives from “Ngola,” or Angola, though there are other theories; in Georgia, the population is known as “Geechee,” the name presumably deriving from the indigenous-named Ogeechee River.

†Writing was taught separately from reading in those days. Slaveowners feared that slaves who could write would forge the passes that every slave traveling alone was required to carry and thus escape.

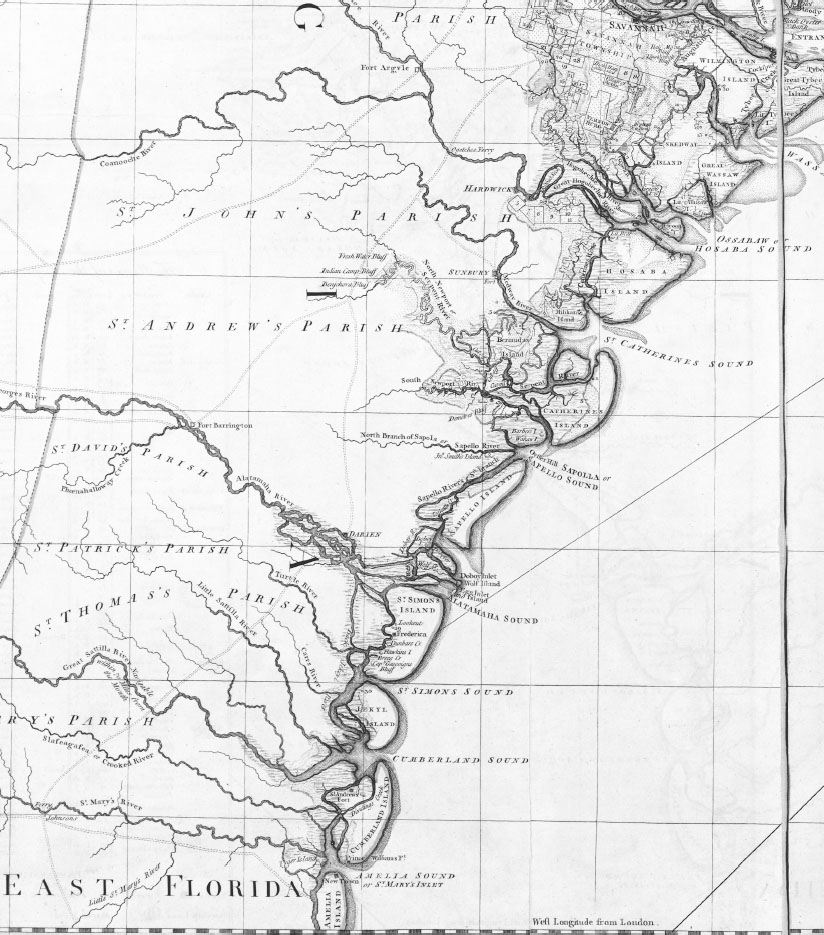

The coast of Georgia as depicted in a British map of 1780, showing the Sea Islands down to Amelia Island, claimed by Florida. Savannah is in the upper right.