26

26 26

26Slaves! … Let us leave that qualifying epithet to the French themselves: they have conquered to the point of ceasing to be free.1

GEORGE WASHINGTON DID NOT live to see Thomas Jefferson become president, nor were the two men on speaking terms when Washington expired, along with the eighteenth century, on December 14, 1799. Washington’s widow, Martha Custis Washington, is said to have thought Jefferson “one of the most detestable of mankind.”2

Lacking South Carolina’s support, Jefferson had lost the 1796 election to John Adams. Open campaigning was at the time thought to be beneath the dignity of a presidential candidate, but as 1800 came around, lest anyone in South Carolina think the emancipation/deportation proposal of Notes on the State of Virginia meant that he was soft on slavery, Jefferson let it be known via Charles Pinckney that he “authorized his friends to declare as his assertion” that the Constitution did not give Congress the right to “touch in the remotest degree the question respecting the condition or property of slaves in any of the states.”3

After a complicated election, culminating in a protracted standoff over a tie vote with Aaron Burr in the House of Representatives, Jefferson prevailed over the incumbent Adams, becoming president on March 4, 1801, with Burr as vice president. For the next twenty-four years, the presidency would be occupied by a “Virginia dynasty” of Jefferson and his protégés—actually, a Piedmont dynasty, from the Shenandoah Valley above the fall line of the James River, where Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe were relative neighbors. During those years (and subsequently, for that matter) foreign and domestic policy alike would reflect the concerns of the Southern states, and specifically Virginia: protecting slavery (which meant expanding it); preventing slave rebellion (which meant isolating Haiti); free trade (with the significant exception, in Virginia’s case, of protectionism for the domestic slave trade); hard money (though an all-metal currency regime was utterly unworkable); a weak federal government (though once the Republicans took power, they came to like wielding it); and a budgetary conservatism that excluded projects for the public good.

Jefferson’s ascent to the presidency was the first peaceful transfer of political power to another party in recorded history. He seems to have truly believed, as he expressed in an 1819 letter, that his election was a “Revolution of 1800” that was as significant a revolution as the one his younger self had personified with the Declaration of Independence.4 The new Democratic-Republican party, usually just known as Republicans but sometimes as Democrats, attempted to implement Jefferson’s philosophy of governance, which proved to be impractical.

Jefferson wanted an agrarian republic, where the “chosen people of God” would “labor in the earth.” For the general operations of manufacture, “let our workshops remain in Europe,” he wrote in Notes, though he subsequently founded a nail factory. He didn’t want there to be cities, which he compared to “sores” on a body, and to that end he starved Washington City of infrastructural funds during his presidency, so that the capital consisted of two magnificent buildings in a malarial, muddy swamp.5

Jeffersonian democracy, as it came to be called, held that states’ rights were paramount, and central government was at best a necessary evil. Debt was an evil to Jefferson, something to be cancelled as quickly as possible. Banks were an evil. Slavery was a great evil, but we have no alternative to the riches it brings.

Keeping a standing army was, as Madison expressed it during the Virginia ratification debate, “one of the greatest mischiefs that can possibly happen.”6 Jefferson attempted to defend the country from foreign aggression entirely by commercial sanction, a method he called “peaceable coercion.” There would be nothing peaceful, however, about the coercion employed domestically to repress slave escape or rebellion. The constitutionally sanctioned “well-regulated militia” could put down rebellions and apprehend black people traveling without a pass, selling them to a trader if no one claimed them.

As president, Jefferson committed to his theory of governance by paying down the debt quickly rather than investing in defense. Moreover, in spite of having a long coastline to defend, he dismantled what military readiness the nation had, reducing the army from five thousand to three thousand, and, in a backhand blow to New England, mothballing the successful United States Navy that Adams had built.

A compulsive tinkerer, Jefferson couldn’t resist refitting the navy, though he had no firsthand knowledge of naval affairs. He was taken with the idea of light, portable gunboats carrying a crew of twenty or so. These were heavily used in the Barbary War that the US Navy fought from 1801 to 1805 in Mediterranean North Africa, although the navy also relied on frigates and brigs in that war. Jefferson’s remarkably bad idea was to make the entire navy into a fleet of the theoretically cheaper gunboats, relying on them as a domestic defense force.

Unfortunately, in that capacity the gunboats were almost useless; vessels that plied the relatively placid Mediterranean couldn’t go to war in the stormy Atlantic, and they were dangerous and demoralizing for the sailors who manned them. They also turned out to be unexpectedly expensive. Some of them, however, were built in Virginia.

President Jefferson pardoned James Callender from his Sedition Act conviction and gave him fifty dollars, one-quarter of his fine, but Callender interpreted the gesture, wrote Jefferson, “not as a charity but a due, in fact as hushmoney.”7 Believing himself entitled to the postmastership of Richmond, Callender turned viciously on Jefferson, publishing their correspondence. In an article published in the Richmond Recorder on September 1, 1802, he broke the story that Jefferson “keeps, and for many years past has kept, as his concubine, one of his own slaves. Her name is SALLY … There is not an individual in the neighbourhood of Charlottesville who does not believe the story; and not a few who know it…. The African venus is said to officiate, as housekeeper at Monticello.” Callender’s role in American history ended the following year, when he drowned while drunk in three feet of James River water on July 17, 1803.

The years of Jefferson’s and, subsequently, Madison’s administrations were years of war between England and France, a war in which the United States was in many ways a participant, even as it declared its neutrality.

In this chaotic maritime war, American merchant vessels fell victim to seizures by predators of both countries. Jefferson had no effective response, and piracy became more common, a situation Jefferson’s gunboats did nothing to abate.

The federal government had for years been trying to stop piracy, which overlapped with the slave trade. Responding to antislavery petitions, Congress passed the Act of 1794, subtitled “An Act to Prohibit the Carrying on the Slave Trade from the United States to any Foreign Place or Country,” which went so far as to provide for money penalties, though not imprisonment, for outfitting vessels for the foreign slave trade. A subsequent congressional measure in 1800 authorized the taking of slavers as prizes, and in the last days of the Adams administration, the US Navy began capturing slavers in the West Indies. In the days of the gunboats, however, enforcement dropped off. During Jefferson’s first term, by one estimate, US slavers carried 16 percent of the African slave trade, up from 9 percent the previous decade.8

Jefferson’s policy toward Toussaint Louverture was markedly different from that of the non-slaveowner John Adams. He refused even to write a personal letter for his new consul to Saint-Domingue to carry to Louverture, as was diplomatic custom, nor would he direct the credentials to Louverture’s attention, sending them merely to “Cap Français,” an insult that Toussaint was quick to perceive.

Saint-Domingue had never declared independence from France, though Toussaint had infuriated Napoleon by sending him a new constitution for Saint-Domingue and declaring himself Governor for Life. As Jefferson described it in a November 24, 1801, letter to James Monroe, in Saint-Domingue “the blacks are established into a sovereignty de facto, and have organized themselves under regular law and government.” Jefferson wrote in the context of wondering whether Saint-Domingue might be a possible colony on which to offload black people “exiled for acts deemed criminal by us, but meritorious perhaps by him.” By “him,” Jefferson meant Toussaint Louverture, but apparently could not bring himself to write the name, referring to him merely as “their present ruler.”9

On this issue, at least, Jefferson and the First Consul coincided. Jefferson’s explicitly racialized hatred of Toussaint was shared by Napoleon, who referred to Toussaint as the “gilded African,” while Jefferson, in a letter to Burr, referred to Toussaint’s men as “the Cannibals of the terrible republic.”10 But Jefferson still didn’t know about Napoleon’s secret plan to occupy Spanish Louisiana when, four months into his presidency, Louis-André Pichon, the French minister to Washington, broached the possibility of an armed French intervention in Saint-Domingue to prevent Toussaint’s declaring independence. Jefferson replied that, given the hostility between Britain and France, Britain had to sign on first. Pichon reported Jefferson’s words back to Paris: “in order that this concert may be complete and effective, you must make peace with England, then nothing will be easier than to furnish your army and fleet with everything and to reduce Toussaint to starvation.”11

To Pichon’s delight, the new President Jefferson, a veteran political intriguer with no military experience, had just conditionally greenlighted a hypothetical invasion of the Americas by Napoleon Bonaparte. But once Jefferson realized the implications for Louisiana, he withdrew his support.

Napoleon instructed Talleyrand in a letter of November 13, 1801, how to spin for British consumption his forthcoming invasion of Saint-Domingue: with racism. A black republic, it was assumed, would be a pirate state and a center of terrorism. Napoleon matter-of-factly wrote of “the course which I have taken of annihilating the government of the blacks in Saint-Domingue.” Without his intervention, he warned, “the scepter of the New World would sooner or later fall into the hands of the blacks … the shock that would result for England [would be] incalculable, even as the shock of the blacks’ empire, as relates to France, has been confused with that of revolution.”12

The British saw Napoleon’s plan for what it was. “The acquisition [of Louisiana],” reported Rufus King, Jefferson’s envoy to Britain, paraphrasing British foreign secretary Lord Hawkesbury, “might enable France to extend her influence and perhaps her dominion up the Mississippi; and through the Lakes even to Canada. This would be realizing the plan, to prevent the accomplishment of which, the Seven Years’ War took place.”13

With the Treaty of Amiens on March 25, 1802, Britain and France made a peace that was more or less a capitulation on Britain’s part. Though Prime Minister Henry Addington would declare war on France less than a year later, for the time being, the peace cleared the way at sea for French intervention in the Americas. While negotiations with Britain were in progress, Napoleon wasted no time in preparing his trusted brother-in-law, General Charles-Victor-Emmanuel Leclerc, to lead an expedition of some thirty thousand men, the largest fleet that had crossed the Atlantic to that date. “Troops were directed to ports, and shipyards in France, Holland and Spain intensified their activity in armaments,” wrote Lieutenant General Baron Pamphile de Lacroix, who served in Leclerc’s campaign. “The purpose of these armaments could not be doubted; they were self-evident … the most superficial observer could conclude, without mental effort, that immediate action was being taken to put Saint-Domingue back under the power of the metropolis.”14

Cap Français in Saint-Domingue was only to be the first landing. While Leclerc’s fleet was crossing the ocean during the brief window of peace between France and England, Jefferson’s minister to France, Robert Livingston, correctly reported to Rufus King on December 30, 1801, that: “I know … that the armament, destined in the first instance for Hispaniola, is to proceed to Louisiana provided Toussaint makes no opposition.”15

Bonaparte’s intention was to invade the hemisphere under cover of subduing a slave rebellion, portraying his move internationally as a preemptive expedition against black terrorists, confining the English-speaking population along the East Coast and eventually driving them out, while controlling the rest of the hemisphere through puppet Spanish and Portuguese kings. Accordingly, Leclerc’s brief was to subdue the noirs of Saint-Domingue, ship their leaders back to France in irons, and then proceed immediately on to Louisiana. Needless to say, Leclerc never complied with the latter instruction, because the black army of Saint-Domingue, together with the Aedes aegypti mosquito, beat the French. Leclerc’s men died of yellow fever even more often than they died in combat with an organized if ill-equipped black military whose soldiers were, terrifyingly, not afraid to die.

When Leclerc’s fleet appeared in Cap Français, Domingan general Henri Christophe burned the newly rebuilt town on February 4, 1802, torching his own house first and repositioning his forces in the mountains. After Leclerc betrayed Toussaint on June 7, kidnapping him to France to die in a freezing mountain prison cell after inviting him to a meeting, the command passed to Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who had formerly served as a general for the French.

At the time Dessalines took charge, Bonaparte still believed he was winning. He wrote to his minister of the marine, Denis Decrès, on June 19, 1802: “My intention is to take possession of Louisiana with the shortest delay, and that this expedition be made in the utmost secrecy, under the appearance of being directed on St. Domingo.”16 In July, the news arrived in Saint-Domingue that Napoleon had signed a decree reinstating slavery in Guadeloupe, and the resistance against France intensified. Dessalines gave an order that he is remembered for: koupe tèt, boule kay—cut off heads, burn houses.

The South was terrified.

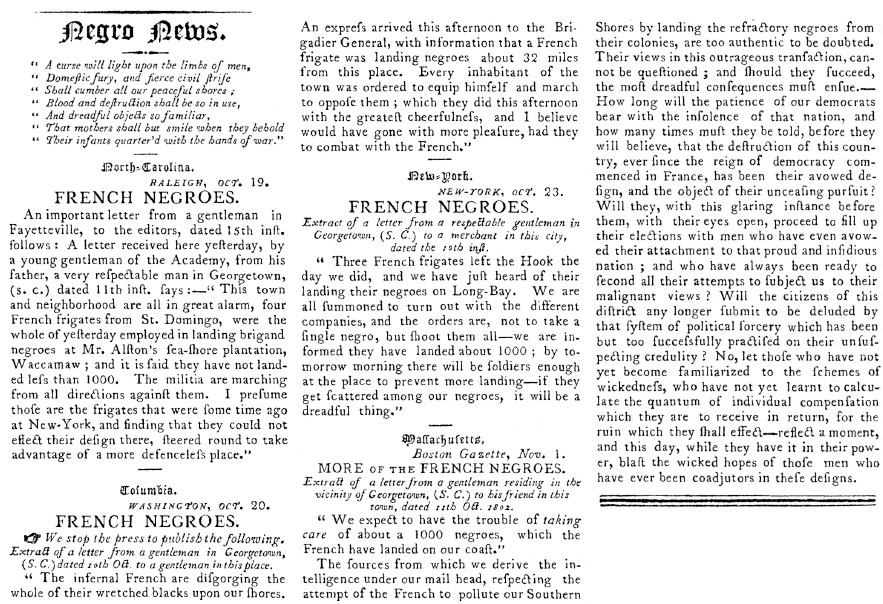

Articles warning of an imaginary invasion of “French Negroes” in the Courier of New Hampshire, November 11, 1802.

Fear of “French negroes” was general, not just in the slaveholding South but in Cuba as well, where slaveowners were prohibited from importing slaves who had lived in foreign colonies, and in Spanish Louisiana.17 A 1797 insurrection plot in South Carolina that may or may not have been real was attributed to “French negroes.” Five years later, as the carnage in Saint-Domingue mounted, a more serious eruption of popular fear had its origin in New York, where, writes Lacy K. Ford, the rumor began that “the French planned to release incendiary black ‘brigands’ up and down the Atlantic coast.” An unidentified ship in the waters near Georgetown, South Carolina, in 1802 set that heavily black area “on the razor’s edge of alarm,” so that “the sighting of a single black man, allegedly of French background, traveling without a pass on a Saturday evening prompted the rapid spread of reports that an armed brigade of French-speaking Caribbean insurrectionists had finally come ashore at Georgetown.”18 In a fit of panic, the state militia was mobilized to resist a phantom invasion. The panic was transmitted in the popular press, as newspapers published accounts describing the imaginary landing of “French negroes.”

While this panic was occurring, the French invaders were dying by the thousands in Saint-Domingue. With Leclerc’s forces dwindling, he embarked on a campaign of genocide, reporting to Napoleon on October 7 that “we must destroy all the mountain negroes, sparing only children under twelve years of age. We must destroy half the negroes of the plains, and not allow in the colony a single man who has worn an epaulette.”19 There were no further communications from Leclerc, who died on November 2 of yellow fever. His successor, General Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, the vicomte de Rochambeau, was the son of the French general who had saved the United States at Yorktown and had served his father as an aide-de-camp during the American war. He attempted to continue Leclerc’s genocide, importing some five hundred bloodhounds from Cuba trained to rip their victims apart, though most of the dogs were apparently eaten by starving French troops.20

Napoleon, who never hesitated to make a far-reaching decision fast and act on it at once, effectively gave up on his American plan when he learned of Leclerc’s death; though he retained Martinique and Guadeloupe, he was determined to spend no more money on Saint-Domingue, where some fifty thousand French soldiers had perished. Already assembling the resources for his coming campaign to conquer Europe, he cut off support for the American venture, leaving his soldiers to twist in the wind without reinforcements. Rochambeau was captured by the British while ingloriously fleeing the island and remained imprisoned for more than eight years.

In Paris, the US ambassador Robert Livingston had been instructed by Jefferson to try to purchase New Orleans and the Floridas. West Florida, with Mobile and Pensacola, was already interdependent with New Orleans for trade, and controlled the access to the sea of the rivers that emptied into the Gulf of Mexico. Without that access, frontiersmen had no outlet for their products. Then a crisis erupted: on October 18, 1802, the Spanish intendant at New Orleans, Juan Ventura Morales, suspended the “right of deposit” that allowed citizens of the United States to transship goods via that port.

Needing to look like he was doing something, Jefferson dispatched Monroe on an “extraordinary mission” to Paris in January 1803, though Livingston was already on the case. “The fever into which the Western mind is thrown by the affair at N. Orleans,” wrote Jefferson in a hasty letter to Monroe, “stimulated by the mercantile, & generally the federal interest, threatens to overbear our peace.”21 Three days later, he wrote Monroe again: “The agitation of the public mind on occasion of the late suspension of our right of deposit at N. Orleans, is extreme.”22

Livingston was no stranger to land deals; as the great-grandson of the landowner and slave trader Robert Livingston, he had inherited the town of Clermont, New York, where the British had burned his mansion during the War of Independence. But he was astounded when Talleyrand offered him not only New Orleans, but the whole vast Mississippi watershed west and north of Louisiana, albeit with little geographical precision—or, more accurately, offered him France’s claim to the territory. By the time James Monroe arrived to join him as a special envoy, sick from his ocean journey, Livingston had already made the deal, though Monroe received the credit for it in America. The price they agreed on for the territory was sixty million francs (approximately $15 million)—a bargain, but enough money that it could fund Napoleon’s war in Europe.

Was it Napoleon’s to sell? The North American purchase in effect legitimated Napoleon’s claim to Louisiana. But it was exactly what Napoleon had promised Carlos IV he would never do. The furious Spanish king took the position that by alienating Louisiana, France had lost its claim and that therefore Louisiana was rightfully Spain’s.

In Charleston, where newspapers had been chiding Jefferson for not acquiring New Orleans, the Louisiana Purchase was seen as a “greater treasure to the western part of the US than a mountain of gold.”23

Acquiring Louisiana was a coup, but Livingston and Monroe had failed to accomplish their mission. They were supposed to get the Floridas along with New Orleans, to lock in the whole Gulf Coast. Instead, they got the west bank of the Mississippi and the uncharted, undeveloped territory upriver.

Florida was an obsession, and a permanent security threat. Controlling the Floridas would secure the entire southeast of the continent from European invasion. It would allow full-scale removal of Native Americans to begin, so that slave-driven plantation agriculture could flourish outward from the slave-supply center of Charleston down into Florida, and through Georgia and Alabama, into Mississippi.

As President Jefferson explained to Congress, the Americans didn’t even have a map of Louisiana.24 No sooner was the Louisiana deal done than Livingston and Monroe—and President Jefferson, and Secretary of State Madison—began claiming that Florida was part of the deal, though they all knew it was not. Florida was still a Spanish possession and had never been ceded to Napoleon. The United States’ baldfaced attempt to claim rights to Florida became the subject of considerable diplomatic wrangling and was a major international issue through the War of 1812 and beyond. Jefferson’s minister to Spain was his South Carolina campaign supporter Charles Pinckney, the Constitution framer from South Carolina, who—unfortunately but typically for an American diplomat—did not speak Spanish.

Historians have argued about exactly why Napoleon made the sudden strategic decision to make Louisiana available to the United States at a fire-sale price, but two motives are clear: one, he wanted money right then for his European war; and, two, he didn’t want the British to have it. Empowering America would provide a check on British expansionism.

That’s certainly what the British thought. They saw Jefferson, as they had since his days in Paris, as a French lapdog, and understandably resented his funding of Napoleon’s war against them. The American Federalists, who sided with Britain against France, were furious.

President Jefferson wanted to get rid of the Indians by the old traders’ device of predatory lending—ensnaring the chiefs in personal debt, then foreclosing on the commons of the tribes they represented. He advocated this method to General William Henry Harrison on February 27, 1803:

to promote this disposition [on the part of the Native Americans] to exchange lands, which they have to spare & we want, for necessaries, which we have to spare & they want, we shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good & influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop th[em off] by a cession of lands.

He continued in a tone that perhaps illustrated how the doctrine of “peaceable coercion” applied at home:

it is essential to cultivate their love. as to their fear, we presume that our strength & their weakness is now so visible that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them.25

The annexation of Louisiana was a political blockbuster. New England was cold to the acquisition, pointing out correctly that Jefferson had exceeded his constitutional limits in making it. But though it was opposed by New Englanders in both houses of Congress—with the significant exception of John Quincy Adams, a pro-expansionist who crossed regional and party lines to side with Jefferson—it approximately doubled the size of US territory overnight. It changed the national balance of power even as the innovations of the cotton gin and a method for making sugar from Louisiana cane made practical the cultivation of these two highly profitable slave-labor crops. Virginia was set to be the primary vendor for the large numbers of slaves that Louisiana planters would want. Jefferson was well aware that a commercial network already existed in which itinerant traders and small-time merchants bought Virginia slaves for trafficking down South, and he knew it was a handy way to get rid of troublemakers, because he took advantage of it repeatedly.

After Cary, one of the imprisoned teenage boys who worked in his slave-labor nail factory at Monticello, attacked another one, Brown Colbert, with a hammer, he was sent away under Jefferson’s orders. “It will be necessary for me to make an example of him in terrorem to the others,” he wrote to his son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph Jr., from the White House on June 8, 1803. “There are generally negro purchasers from Georgia passing about the state, to one of whom I would rather he should be sold than to any other person. [I]f none such offers, if he could be sold in any other quarter so distant as never more to be heard of among us, it would to the others be as if he were put out of the way by death.”26

Jefferson, then, was not only well aware of the Georgiamen and their southbound interstate slave trade, but also understood their process as a tool with which to terrorize—“in terrorem to the others”—his factory’s workers, who were imprisoned children, and who had a cash value even as felons.

Louisiana’s Anglo-American settlers were primarily from Kentucky, a territory that had been carved out of Virginia and settled by Virginians. While the Louisiana Territory was being organized, President Jefferson sent his proven ally John Breckinridge—now a senator from Kentucky—a top-secret letter on November 24, 1803, enclosing two cramped double-column pages of proposals for a markedly undemocratic rule of Louisiana by a pro-American oligarchy that he referred to as an “Assembly of Notables.” As with the previous Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson cautioned Breckinridge to pass the work off in the Senate as his own and not reveal his hand in it:

In communicating it to you I must do it in confidence that you will never let any person know that I have put pen to paper on the subject and that if you think the inclosed can be of any aid to you will take the trouble to copy it & return me the original. I am this particular, because you know with what bloody teeth & fangs the federalists will attack any sentiment or principle known to come from me, & what blackguardisms & personalities they make it the occasion of vomiting forth.27

It was the first time that Congress had dared contemplate making any determination as to whether slavery should be allowed somewhere, but there was no alternative if the territory was to be organized. Breckinridge put forth Jefferson’s proposals as his own, perhaps with some modification (no copy survives of his bill as introduced). Having amply demonstrated his loyalty, he became Jefferson’s attorney general in 1805.

For our purposes, the most interesting feature of Jefferson’s plan for Louisiana as contained in the Breckinridge-tendered proposal was that he wanted to prohibit the foreign slave trade but allow the domestic. There was no question that Louisiana would continue to buy imported slaves. The payday for Virginia slaveholders was that slaves could not be brought to Louisiana from Africa or Havana, but would have to be imported from the United States—a move that substantially revalued every Chesapeake slaveowner’s holdings upward and substantially increased Virginia’s share of the nation’s capital stock.

But on the same day Jefferson wrote Breckinridge, South Carolina’s governor James Richardson sent a message to his state’s General Assembly calling for the reopening of the foreign slave trade to South Carolina.28 The following day, Jefferson wrote Breckinridge again, adding text to his previous letter: “Insert in some part of the paper of yesterday ‘Slaves shall be admitted into the territory of Orleans from such of the United States or of their territories as prohibit their importation from abroad, but from no other state, territory or country.’ salutations. Nov. 25. 1803.”29

Jefferson’s added clause was specifically aimed at denying South Carolina the right to import slaves for reshipment to New Orleans. Though Jefferson’s general plan became law, the prohibition of importation from South Carolina did not survive; when the Louisiana bill came before the Senate, James Hillhouse, a Connecticut Federalist, attached an amendment that prohibited slaves from “without the limits of the United States,” but made no other distinction. With legal obstacles removed, South Carolina unilaterally and legally reopened the African slave trade in order to service Louisiana with freshly imported Africans rebranded as domestic product, undercutting the Virginia slaveowners substantially.30

The United States formally took possession of Louisiana from France on December 20, 1803, twelve days before Commander in Chief Jean-Jacques Dessalines issued the Haitian Declaration of Independence that proclaimed the existence of the Republic of Haiti on January 1, 1804. It largely consisted of an extended and strongly worded cry of hatred for France, but nevertheless offered an olive branch to the rest of the hemisphere that acknowledged the fear that Haitians would become exporters of terrorism:

Let us ensure, however, that a missionary spirit does not destroy our work; let us allow our neighbors to breathe in peace; may they live quietly under the laws that they have made for themselves, and let us not, as revolutionary firebrands, declare ourselves the lawgivers of the Caribbean, nor let our glory consist in troubling the peace of the neighboring islands.

But then Dessalines went from town to town, personally supervising the execution of the French remaining in the territory—while exempting the Polish soldiers who had fought on the side of the Haitians, who were made honored members of the new society, and the many US captains who were happily doing business in the ports of the new republic. Dessalines served as Haiti’s first president for less than three years before being murdered by other Haitians, and ultimately (unlike the Catholic Toussaint) became a lwa of Haitian vodou.31

James Wilkinson was upset to see the black militiamen of New Orleans in uniform and carrying weapons. A traitor who acted as a Spanish secret agent while commanding the US Army, Wilkinson had previously proposed that Kentucky declare independence from Virginia and become allied with Spain instead. But he nevertheless was tolerated by Jefferson, who made Wilkinson the head of the US Army in Louisiana.

Jefferson’s Virginian-via-Tennessee protégé, W. C. C. Claiborne, a blue-blood descendant of Kent Island’s William Claiborne, became the territorial governor of Louisiana. Claiborne, who spoke neither French nor Spanish, had since 1801 been governor of Mississippi, a position awarded him by Jefferson. As the Americans took charge in Louisiana, Claiborne’s agent Dr. John Watkins, who had reconnoitered the country, pointed out in a report of February 2, 1804, the most important political issue:

No Subject seems to be so interesting to the minds of the inhabitants of all that part of the Country, which I have visited as that of the importation of brute Negroes from Africa. This permission would go farther with them, and better reconcile them to the Government of the United States, than any other privilege that could be extended to the Country. They appear only to claim it for a few years, and without it, they pretend that they must abandon the culture both of Sugar and Cotton. White laborers they say, cannot be had in this unhealthy climate.32

The “Kaintucks”—a minority in Louisiana—had a marked preference for American-born slaves. But the Creoles of Louisiana wanted slaves from Africa. They didn’t want English-speaking slaves, they didn’t want Protestant slaves, and they didn’t want to pay the much higher prices charged by the speculators who brought slaves from Virginia and Maryland.

Claiborne wrote to Madison on March 10, 1804, of unrest on the part of both planters and slave traders:

In a Paper which was received by the last Mail from the Seat of Government, it was stated that a Law had passed the Senate prohibiting the foreign importation of Slaves into this Province. This intelligence has occasioned great agitation in this City and in the adjacent Settlements.

The African Trade has hitherto been lucrative, and the farmers are desirous of increasing the number of their Slaves. The prohibiting the incorporation of Negroes therefore, is viewed here as a serious blow at the Commercial and agricultural interest of the Province. The admission of Negroes into the state of South Carolina has served to increase the discontent here. The Citizens generally can not be made to understand the present power of the State Authorities with regard to the importation of persons:—they suppose that Congress must connive at the importation into South Carolina, and many will be made to believe, that it is done with a view to make South Carolina the Sole importer for Louisiana.33

And, indeed, that is what happened. Louisiana was a colonized territory, and as such, it was subject to trade restrictions that benefitted the metropolis—principally Virginia, but Carolina had found a way to horn in.

Claiborne’s power during the territorial era was frequently and not inaccurately described as dictatorial, though the picture that emerges from his letters is that of a man who has a French-speaking tiger by the tail.* Contemplating the impending prohibition of both the African slave trade and the interstate trade to Louisiana as of October 1, he wrote Secretary of State Madison on May 8:

I am inclined to think that previous to the 1st of October thousands of African Negroes will be imported into this Province; for the Citizens seem impressed with an opinion, that a great, very great supply of Slaves is essential to the prosperity of Louisiana: Hence Sir you may conclude that the prohibition as to the importation Subsequent to the 1st of October, is a source of some discontent; Nay Sir, it is at present a cause of much clamour.34

And on July 12:

At some future period, this quarter of the Union must (I fear) experience in some degree, the Misfortunes of St. Domingo, and that period will be hastened if the people should be indulged by congress with a continuance of the African Trade.

African Negroes are thought here not to be dangerous; but it ought to be recollected that those of St. Domingo were originally from Africa and that Slavery Where ever it exists is a galling yoke. I find however that an almost universal sentiment exist in Louisiana in favour of the African traffic…. Slaves are daily introduced from Africa, many direct from this unhappy Country and others by way of the west India Islands. All vessels with slaves on bord [sic] are stopped at Plaquemine, and are not permitted to pass without my consent. This is done to prevent the bringing in of Slaves that have been concerned in the insurrection of St. Domingo.35

The foreign slave trade into Louisiana was never again legalized. But under pressure from Jefferson to respond to Claiborne’s urgent drumbeat that the citizens of Louisiana wanted more slaves, Congress legalized the domestic slave trade to Louisiana in March 1805, to be fully effective October 1.

That the black territory freed from France should call itself a republic was seen by whites as a grotesquerie.

For the slaveowners in the United States government to have diplomatic relations with slaves who had killed their masters was unthinkable; it would, they thought, amount to rewarding their actions. Although Haiti was the second republic in the hemisphere, the United States didn’t extend diplomatic recognition to it until 1862, and then only because President Abraham Lincoln saw it as a potential site for “colonization,” or deportation, of emancipated slaves.

Yet the Southerners owed the Haitians a lot. At a time when Washington, DC, was a squalid, barely built village and the US Army had only about three thousand troops, Haiti stopped the French troops’ forward march into the Americas. To put it another way: though it was not their objective, Dessalines and his troops prevented Bonaparte’s forces from invading Louisiana and controlling commerce on the Mississippi. Historians don’t deal in counterfactuals—what might have happened—but it is tempting to imagine scenarios: if Leclerc had been able to comply with his orders to continue on from Saint-Domingue and occupy Louisiana with ten thousand men or more, controlling the great New Orleans gateway to the sea? Could the French have managed a permanent occupation that would have been hard to dislodge? Certainly the United States governing class had not expected to be able to expand across the continent so quickly and easily.

Spain’s military involvement in Saint-Domingue was its last gasp as a world power, the prelude to losing its colonies one by one, and Saint-Domingue was the graveyard of British colonial expansion in the Americas as well. The expense and horrendous loss of life were a spur to the British in stopping the African slave trade—though not British colonial slavery, yet—via an act approved in Parliament on March 25, 1807, a mere three years after the establishment of the Republic of Haiti.

Britain could afford to get out of the slave trade. As profitable as slaving could be, British commerce was so large, and so diverse, that losing the slave trade didn’t make a dent it. Trinidad, Britain’s last-acquired Caribbean colony, was ceded to Britain by France in 1802. It had been Spanish, French, and now English in succession. The Africans who were subsequently brought to Trinidad were not brought as chattel slaves but as indentured workers from the British empire in Africa.*

New England merchants did a brisk business in Haiti, to the disgust and alarm of Southerners, trading arms along with other commodities and consumer goods. Napoleon, who refused to recognize Haitian independence, was furious about American commerce with Haiti; Jefferson, who hoped to have Napoleon’s cooperation in taking over Florida, wanted to keep him happy. Congress passed sanctions against commerce with Haiti in 1806, amid arguments that to trade with Haiti against France’s wishes was to recognize Haitian independence. That would be, Jefferson’s son-in-law John Wayles Eppes shouted in the House, “a system that would bring immediate and horrible destruction on the fairest portion of America.”36

Southerners were on permanent high alert for terrorism, and never backed down. The specter of Haiti informed all future discourse—every dinner-table conversation, every political calculation, every speech—about slavery in the Southern United States. The “French Negroes” were thought to carry the contagion of insurrection, and prophylactic measures were thought necessary to keep them from infiltrating; there was even concern, utterly unwarranted, that Haiti might attack the United States.

Here as on other occasions, Southern slaveowners revealed how terrified they were by the ferocity of black fighters. Haiti had a significant population of black men who had served in European and/or African armies or in colonial militias, and their military knowledge embraced both European and African military tactics and systems of organization.

The clock was ticking. The Constitution allowed the federal government to stop the foreign slave trade as of January 1, 1808, and President Jefferson wanted that trade shut down for good. Prohibiting the slave trade was easily represented to a panicked public as antiterrorism.

But it also partook of that other great issue: prohibiting the African slave trade protected the market so that a new class of American traders could come forward, supplied with homegrown captives born into slavery on Virginia and Maryland farms. The conditions were right for a massive forced migration of enslaved Chesapeake laborers down South, and it did not have to be a one-time drain: a continuing domestic slave-breeding industry was now possible.

This was something new. Taking the long historical view, African American historian William T. Alexander wrote in 1887:

Slave breeding for gain, deliberately purposed and systematically pursued, appears to be among the latest devices and illustrations of human depravity…. That it was cheaper to buy slaves than to rear them, [had been] quite generally regarded as self-evident. But the suppression of the African slave trade, coinciding with the rapid settlement of the Louisiana purchase and the triumph of the Cotton Gin, wrought here an entire transformation. When field hands brought from ten to fifteen hundred dollars, and young slaves were held at from ten to fifteen dollars per pound, the newly born infant, if well formed, healthy, and likely to live, was deemed an addition to his master’s stock of not less than one hundred dollars, even in Virginia and Maryland. It had now become the interest of the master to increase the number of births, in his slave cabins, and few evinced scruples as to the means whereby this result was obtained.37

The Spanish had had the most permissive slave regime ever to exist in the territories that now make up the United States. Under Spanish law, the enslaved had a right to have a hearing to establish a price by which they could purchase their freedom. This practice, called coartación, was hated by the planters, and it ended in 1807.

In Louisiana, both free people of color and the enslaved found themselves in transition to the hemisphere’s psychologically harshest racial regime: the Anglo-American mode of slavery, which provided no path to freedom even for future generations of descendants. The Virginians brought them a kind of slavery that was not only lifelong, but perpetual.

*When in 1807 Jefferson tried to prevail on James Monroe to take the Louisiana governorship, he pitched it as the “2d office in the US. in importance.” PJMon, 5:288.

*The old ways persisted, however; Trinidad’s carnival was a Mardi Gras, and when its characteristic musical form of calypso later appeared, it was in the French Creole tongue, as were many of the old bombas of western Puerto Rico, where Domingans also went.