31

31 31

31I do believe that Virginia is become another Guinea, and the Eastern Shore an African coast.

I have known what it is to be dragged fifteen miles to the human flesh market and be sold like a brute beast. I am from a slave-breeding state—where slaves are reared for the market as horses, sheep, and swine are.1

ALREADY THE DOMINANT COMMERCIAL American city, New York took a major step toward consolidating its supremacy at the beginning of 1818, when “packet” boats began running monthly between New York and Liverpool.

Packets left at a scheduled departure time whether they were full of cargo or not, making shipping more predictable, and they had to do it in all kinds of weather, fighting their way across from Liverpool to New York even if it was stormy and icy. Especially in winter, the westbound, or “uphill,” trip from England to America, going against the Gulf Stream, was the most dangerous passage a sailor could make, anywhere in the world. Because vessels couldn’t sail directly against the prevailing westerly winds, they had to “tack”: set their sails at a forty-five-degree angle to the wind in a series of successive adjustments that allow the craft to make an arc in the windward direction. Accordingly, they traveled farther than they would have, and much slower, than if the winds had been in their favor. Ships sailing from England to America typically could expect to travel anywhere from four to seven hundred miles more than when they were going the other way.2

The Gulf Stream was also an obstacle for the American coasting trade southward down around Florida to New Orleans. North Carolina was a navigational menace, with sandbars outlining its shores; Capes Hatteras, Lookout, and Fear all posed dangers for passing vessels. But it was also where vessels began to have to go against the Gulf Stream. Then, going around Florida, there were coral reefs, shoals, keys, sandbars, eddy currents, and shallow water, to say nothing of the difficulty of passing through the Straits of Florida against the force of the current. Maritime insurers rated the accident rate from New York to New Orleans at 1¼ to 1½ percent, more dangerous than the trip from New York to Liverpool though not more dangerous than the trip from Liverpool to New York.3

New York’s monopolization of the carrying trade was bitterly resented by the cotton growers of the South, but there was nothing they could do. Even from Charleston, the “great circle” northern route was the shortest way from America to England. Though wealthy planters were beyond-conspicuous consumers, there were so few of them that the South didn’t buy enough imports to make regular direct round-trip transatlantic shipping from Liverpool to Charleston worthwhile—ships would have arrived in America with their holds full of ballast. The shipping profit from sending cotton out and receiving imported goods in return went to New York, where the products were handled.

Coasting packets took Carolina and Georgia cotton to New York, where it was loaded onto transatlantic packets. When ships arrived at New York carrying merchandise from Britain, the part of it that was destined for the Lowcountry traveled on a coasting packet, so British goods cost more in South Carolina than they did in New York. And needless to say, when specie was shipped from Britain to pay for purchases, it came to New York.

Baltimore had the best harbor in the Chesapeake, and some of the best shipping facilities in the country, but it had no chance of competing with New York for European commerce. Instead, it was perfectly positioned to specialize in servicing the expanding domestic market, and it grew with the republic. Its shipyards built the lightweight, high-speed schooners that began darting back and forth along the coast as packets, bringing regular news from one place to another. The run was especially profitable between Baltimore and New Orleans: since both cities were rich emporia, ships could go full in both directions.

Maryland, a border state with diversified agriculture that counted a number of Quakers in its population, was increasingly divided over slavery. On the Eastern Shore, there was much slave agriculture but also antislavery sentiment. In the northern part of the state especially, slavery was on the decline after 1820, as it was in Delaware. Limited terms of service were becoming increasingly common for Maryland slaves, raising them almost to the category of indentured servants. Slave-sale advertisements naming individuals generally specified whether they had a term of service or were “slaves for life.”

Fast-rising Baltimore had slave labor, but it was not a slave society the way Richmond or Charleston was. Seth Rockman describes the diverse mix of the early nineteenth-century Baltimore workforce as “a continuum of slaves-for-life to transient day laborers—with term slaves, rented slaves, self-hiring slaves, indentured servants, redemptioners, apprentices, prisoners, children, and paupers occupying the space in between.” He argues that the reason slavery remained viable in the dynamic Baltimore labor market at all was the enslaved laborer’s capitalized value: “the perpetuation of slavery in a place like Baltimore owed less to the actual labor compelled from enslaved workers and more to the fact that plantation purchasers in Charleston, Augusta, New Orleans, and throughout the South were willing to pay hundreds of dollars for Baltimore slaves.”4

One of those enslaved laborers in Baltimore was Frederick Douglass, who ultimately escaped on a boat leaving the port. Though he remembered that “going to live at Baltimore laid the foundation, and opened the gateway, to all my subsequent prosperity,” while working as a hired slave at the Fell’s Point shipyard he was beaten by “four of the white apprentices” in a fight “in which my left eye was nearly knocked out, and I was horribly mangled in other respects.” He described the relations between classes of laborers there:

The white laboring man was robbed by the slave system of the just results of his labor, because he was flung into competition with a class of laborers who worked without wages. The slaveholders blinded them to this competition by keeping alive their prejudice against the slaves as men—not against them as slaves. They appealed to their pride, often denouncing emancipation as tending to place the white working man on an equality with negroes, and by this means they succeeded in drawing off the minds of the poor whites from the real fact, that by the rich slave master they were already regarded as but a single remove from equality with the slave. The impression was cunningly made that slavery was the only power that could prevent the laboring white man from falling to the level of the slave’s poverty and degradation.

To make this enmity deep and broad between the slave and the poor white man, the latter was allowed to abuse and whip the former without hindrance…. these poor white mechanics in Mr. Gardiner’s ship-yard, instead of applying the natural, honest remedy for the apprehended evil, and objecting at once to work there by the side of slaves, made a cowardly attack upon the free colored mechanics … The feeling was, about this time, very bitter toward all colored people in Baltimore, and they—free and slave—suffered all manner of insult and wrong.5 (paragraphing added)

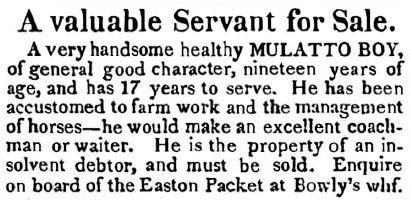

The Baltimore waterfront was a key site for slave trading. There were twenty-four wharves along the harbor, to any one of which Maryland captains of local packet-boats coming from Easton, Chestertown, Kent Island, or other Eastern Shore points of origin might bring along a slave or two to sell. Most were sold without newspaper ads, but some surviving examples testify to the practice.

Baltimore American and Commercial Daily Advertiser of December 21, 1818. This nameless “mulatto,” sold in payment of a debt, might have remained in Baltimore, perhaps hired out at the shipyard by his new owner, or perhaps ultimately taken down South. In the latter case, it is doubtful that his freedom date seventeen years hence would have meant much.

It is clear that there was already an export market for slaves out of Maryland by this time, though not much direct documentation of it survives. An 1816 grand jury report in Baltimore stated:

There are, in this city, houses appropriated to this trade, as prisons for the reception of the Negroes intended to be carried to other states. Slaves are crowded together, male and female, in one common dungeon. They are loaded with irons, confined in their filth, and subjected to various species of cruelty and tyranny from their keepers.6

The earliest shipment of slaves by water from Baltimore to New Orleans of which we have a record—though clearly not the first to take place—was in December 1818, when, in Ralph Clayton’s description, “twenty-four slaves, boarded by six different shippers, were brought to the dock over a four day period” to be put on the brig Temperance.7 In addition to slaves consigned from traders on the hard sail South, the packets might take migrating farmers transporting their labor forces, or passengers accompanied by enslaved personal servants.

Austin Woolfolk Jr. was only nineteen when he began running his CASH FOR NEGROES advertisements in the Baltimore press in 1816, almost as soon as the coast was clear of the British.8 Working with his father, he had built up a stake in his hometown of Augusta, Georgia, by supplying slaves to planters relocating to newly available Alabama land.9 There were no quantities of slaves available in cotton-mad Georgia, so he went northward in search of supply—to the farmers of Maryland’s Eastern Shore, whose eagerness to sell slaves had already been amply demonstrated.

Woolfolk was not the first slave trader to offer cash in newspaper advertisements, but he became emblematic of the practice. Spending liberally on advertising, traders helped anchor the Upper South’s newspaper industry, running ads in every issue, all season long, of every small-town paper in their regions of coverage. Most merchants handled a variety of merchandise, but Woolfolk, who embraced as part of his pitch the term “Georgiaman,” dealt only in slaves, and unlike other slave traders, he did not run coffles, but only shipped captives by water.

To maximize profits, a slave trader had to cover both ends of the transaction: buy young people cheaply from farmers in Virginia and Maryland, transport them to the Deep South, and sell them there at premium prices. Woolfolk could bypass intermediaries by canvassing farms directly, offering farmers more for young African Americans than the Richmond-bound traders could. That meant having operations at both ends, with all the complexities of interstate law, taxation, and banking, all the complications of transport, and a large network of contacts. It meant a cash-flow-intensive business that had to respond quickly to changing political, economic, or weather conditions, and it entailed having offices and slave-processing facilities in different cities, with partners or agents in those cities. In Woolfolk’s case, as with many merchants, his family provided them.

The Woolfolks developed the most effective network for canvassing the farms of the Eastern Shore for slaves to buy, establishing a base of operations headed by Woolfolk’s brother Joseph at Easton. Once the harvest was in and farmers were ready to sell, Woolfolk’s agents scoured the area, visiting every farm they could. Throughout the region they established temporary headquarters at one or another inn, distributed handbills, and took out CASH FOR NEGROES newspaper ads. They sailed the captives downriver to the Chesapeake Bay and on to Baltimore, where they were held in Woolfolk’s jail until he had a full gang for shipment.

Woolfolk “generally consummated just a few sales at a time” when buying in Maryland, writes William Calderhead, “and from one to four slaves per purchase. Most chattels were in their teens and males outnumbered females by a ratio of 8 to 5. Slaves were not purchased in families, but on occasion a mother and child would be acquired as a unit.”10 But only “on occasion.”

Like everyone else in his trade, Woolfolk routinely separated families. John Thompson, born in Maryland in 1812 on a plantation with about two hundred slaves, had as one of his earliest childhood memories a visit to the jail where his sister was about to be sold, as his mother wept:

the first thing that saluted my ears, was the rattling of the chains upon the limbs of the poor victims. It seemed to me to be a hell upon earth, emblematical of that dreadful dungeon where the wicked are kept, until the day of God’s retribution, and where their torment ascends up forever and ever.

As soon as my sister saw our mother, she ran to her and fell upon her neck, but was unable to speak a word. There was a scene which angels witnessed; there were tears which, I believe, were bottled and placed in God’s depository, there to be reserved until the day when He shall pour His wrath upon this guilty nation.11

The slave-buyers chatted up the locals to find out who might be going out of business, who needed cash, who might have an extra laborer to sell. It was much like what horse traders did, and not a few people who wound up doing this kind of work were former horse-traders who had moved over into trading in slaves; their successors would move back to selling horses again after emancipation. The working vocabulary of the slave trade overlapped that of the livestock business, as per the use of a term like “stock”—specificially a breeding term—to describe a labor force.

A few slave dealers advertised themselves as “negro traders,” but most were identified more generically as brokers, commission merchants, auctioneers, et cetera. The network of the slave trade was not limited to the trader’s own agents. The commerce spread its largesse around Maryland, and especially around Baltimore, through an informally organized network whose meeting-places were inns and taverns, some of which were especially known for their involvement in the business. “Bartenders were often used as agents,” writes Ralph Clayton. “Their exposure to numerous travelers … placed them in an ideal position to act as go-betweens. A number of ads often reflected the seller or buyer’s desire to have information left ‘at the bar.’”12 Clayton has compiled a list of Baltimore spots where traders did business: Mr. Lilly’s Tavern, Fowler’s Tavern, Fountain Inn, Sinner’s Tavern, Mrs. Kirk’s, the General Wayne Inn, William Fowler’s, John Cugle’s, the Columbian Hotel, the Globe Hotel, et cetera. This pattern was consistent throughout the South, where hotels commonly had secure lockup rooms that ranged from individual cells to full-fledged jails.

Slave jailing was an informally organized, widely distributed system of forprofit prisons. Traders in many towns maintained their own jails, which passing coffle-drivers could use, with the advantage of possibly being able to sell or buy through contacts there. In other towns, the local lawman might be happy to rent space in the town jail for a night. Speaking of the 1850s, Bancroft wrote:

Every Southern city, and some mere villages, had slave-jails, slave-pens, or slave-yards, as they were variously called. They differed much in size and character. Some were carefully built, while others were old buildings, houses, sheds or stables, slightly altered. They usually had some of the characteristics of a poor barrack, a boarding stable and a prison…. At the best of the public ones, where slaves were fed and watched for any stranger, the usual charge was twenty-five or thirty cents a day—hardly as much as the feeding and care of a horse at any public stable. Their food was almost as plain as a horse’s and they often had less that could be called a bed. They slept on the hard floor, and considered themselves fortunate if, in addition to their bundle of clothes, which they used for a pillow, they could get an old blanket.13

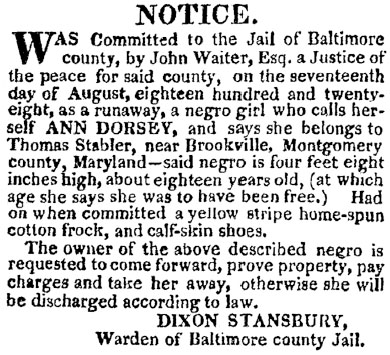

One of nine such advertisements in an issue of the Easton, Maryland, Gazette, October 18, 1828.

Local sheriffs were good contacts for Woolfolk’s agents, because they were in a position to flip runaways, whose disgusted owners might authorize handing them over to Woolfolk in exchange for a cash settlement, or who might be sold unclaimed. Surviving records from Baltimore show fifteen handovers of runaways to him between 1829 and 1836: Liz, on August 10, 1835; Kitty, on November 5, 1835; Henry Hazelton, December 3, 1835, et cetera.14

Some “runaways” might be free people kidnapped off the street, as in the case of Fortune Lewis, who was abducted in 1822, taken to Woolfolk’s jail, and sent to Washington, where he was able to prove his freedom and was released.15 But such a happy resolution for the victim was unusual. The free black people of Baltimore—and, indeed, free black people throughout the North—lived with the knowledge that they could be kidnapped and sold.

Austin Woolfolk’s early growth was slowed by national economic difficulties. Much as the First Bank of the United States had previously done in 1792, the Second Bank of the United States caused a panic soon after it was chartered.*

The depression remembered as the Panic of 1819 took two years to bottom out and two more to come back, though its effects were lighter in the newly wealthy Deep South. “Not till 1821 did [Woolfolk] ship more than one hundred slaves south annually,” writes Calderhead. That was the year he moved into his Pratt Street quarters, complete with his own slave jail. “In the following year his scale of operations doubled, and for the next six years he shipped from 230 to 460 slaves south on an annual basis.”16

Woolfolk’s main source of supply was the farms of Maryland’s Eastern Shore; like those of Virginia, their well-fed, hard-working young farmhands were established as a premium brand. Calderhead notes that “as for sellers, many who dealt with the traders once were inclined to do so again.”17 For those repeat vendors, selling slaves had become a regular part of their economic cycle—which is to say, they had become slave-farmers who sold perhaps one or two teenagers a year.

Like many traders, Woolfolk lived on his jail site, in a house that was part of a complex where dozens of people might be chained up at a time. The size of Woolfolk’s operation made him the public face of the “negro-trader” and his name the terror of the enslaved. He had a kind of bogeyman status for enslaved children—except, unlike the bogeyman, he was real.

Frederick Douglass grew up in fear of Woolfolk. Like many who were born enslaved, Douglass had been separated from his mother at an early age and did not know the exact date of his birth, which he reckoned to have been in 1818. Before he was hired and sold away, Douglass was one of about a thousand people Edward Lloyd owned on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, near Easton. That kind of estate took generations to accumulate; Lloyd was descended from seventeenth-century Maryland old money, and the core of his property is still in the hands of his descendants today. Lloyd was at various times a congressman, senator, and the governor of Maryland; it is ironic that he is most remembered for owning the plantation where Frederick Douglass was born and lived as a child.

Lloyd’s captives labored on a network of neighboring agricultural prisons administered from a central location. Douglass, who described the brutalities of Lloyd’s regime, recalled of the central plantation that “if a slave was convicted of any high misdemeanor, became unmanageable, or evinced a determination to run away, he was brought immediately here, severely whipped, put on board the sloop, carried to Baltimore, and sold to Austin Woolfolk, or some other slave-trader, as a warning to the slaves remaining.”18

Woolfolk accounted for 53 percent of the 4,304 people documented as sent by the oceangoing trade from Baltimore to New Orleans between 1819 and 1831, but despite his outsized historical footprint, there were many other traders. A person with “Negroes of either sex to dispose of” might, for example, stop by the New Bridge Hotel and leave word for the Kentucky trader David Anderson, who accounted for 223 of the 1,400-plus people known to have been shipped by water from Baltimore to New Orleans between 1818 and 1822.19

Woolfolk knew better than to parade the grim spectacle of loading his ships before the eyes of the town. When it was time to sail, the captives were marched under cover of predawn darkness out of his complex, located near present-day Oriole Park, down seven or so blocks to Fell’s Point. From there, they sailed around the peninsula of Florida, and many were ultimately sold out of the Woolfolk firm’s New Orleans office at 122 Chartres Street. Others were taken to Natchez, where Woolfolk also sold slaves, as an advertisement in the Woodville, Mississippi, Republican that ran for three months in late 1826 / early 1827 announced:

NEGROES FOR SALE. The subscriber has on hand seventy-five likely young Virginia born Negroes, of various descriptions, which he offers to sell low for cash, or good acceptance; any person wishing to purchase would do well to call and suit themselves. — I will have a constant supply through the season. — I can be found at Purnell’s Tavern.

Natchez, December 1st, 1826. “Austin Woolfolk.”20

Frederick Douglass recalled:

When a child … I lived on Philpot Street, Fell’s Point, Baltimore, and have watched from the wharves, the slave ships in the Basin, anchored from the shore, with their cargoes of human flesh, waiting for favorable winds to waft them down the Chesapeake. There was, at that time, a grand slave mart kept at the head of Pratt Street, by Austin Woldfolk [sic]. His agents were sent into every town and county in Maryland, announcing their arrival, through the papers, and on flaming “hand-bills,” headed CASH FOR NEGROES. These men were generally well dressed men, and very captivating in their manners; ever ready to drink, to treat, and to gamble. The fate of many a slave has depended upon the turn of a single card; and many a child has been snatched from the arms of its mother by bargains arranged in a state of brutal drunkenness.

The flesh-mongers gather up their victims by dozens, and drive them, chained, to the general depot at Baltimore. When a sufficient number have been collected here, a ship is chartered, for the purpose of conveying the forlorn crew to Mobile, or to New Orleans. From the slave prison to the ship, they are usually driven in the darkness of night; for since the antislavery agitation, a certain caution is observed.

In the deep still darkness of midnight, I have been often aroused by the dead heavy footsteps, and the piteous cries of the chained gangs that passed our door. The anguish of my boyish heart was intense; and I was often consoled, when speaking to my mistress in the morning, to hear her say that the custom was very wicked; that she hated to hear the rattle of the chains, and the heart-rending cries. I was glad to find one who sympathised with me in my horror.21

A coastwise trip took three weeks or so, depending on the weather, versus seven or eight weeks to make the grueling walk from Maryland to New Orleans. Economic historians Herman Freudenberger and Jonathan B. Pritchett found that eight passages—“shipments” was the term—from Norfolk to New Orleans took an average of nineteen days in transit, at a cost of seventeen dollars per slave. But the transit time, they found, was only 18 percent of the time elapsed between receiving a certificate of good conduct (affirming that the enslaved person in question was not dangerous) and sale.22 The time of actual transport was sandwiched between weeks of being held in pens at either end. Though an individual interstate trade could be a process of between two and three months, there were cases that took a year—a process of mental agony for the captive. Enslaved women were frequently pregnant, and on occasion women gave birth while in a holding pen or at sea.

The advantages of coastal speed over the overland trade were obvious. Coastal trade turned capital around quicker, essential in a cash-intensive business; market conditions could be responded to more quickly; a minimum of two weeks’ expenses of provisions was saved; and, most important, the enslaved arrived in better condition—especially children, who had a hard time keeping up with a coffle’s pace—which meant a higher price. There were relatively few onboard fatalities among these young people, who had, after all, been selected for their relative health and appeal.23 Long months of confinement in pens, followed by weeks at sea, facilitated the spread of diseases, but these were not the Middle Passage crossings that averaged something like a 15 percent mortality en route.

The inward shipping manifests show a disturbing phenomenon one digit at a time: the number of children under ten sold away from their mothers and sent for sale alone. Louisiana put a stop to that in 1829 with a unique law that harmonized with the rules of the old Code Noir, prohibiting the sale of children under ten without their mother unless documented proof of orphanhood was furnished. “This statute markedly lowered the number of sales in Louisiana of out-of-state, unaccompanied young slave children,” writes Judith K. Schafer. “Immediately before passage of this law, 13.5 percent of the slaves sent from Virginia to New Orleans were under the age of ten years. Immediately following passage of the act, shipments from Virginia of slave children under ten declined to 3.7 percent, and none of these were unaccompanied by their mothers.”24 Which is to say that, in Austin Woolfolk’s heyday, until a regulation to control it was implemented, 9.8 percent of the involuntary passengers shipped south were motherless children under ten. For that matter, most of the rest of the passengers were little more than children, in the early years of their reproductive lives. Ninety-three percent of the enslaved people whose passage Freudenberger and Prichett could document were between the ages of eleven and thirty. But then, it was a young country. Black or white, people didn’t live all that long. Over 40 percent of Baltimore was fifteen or younger in 1820.25

There were dangers connected with oceangoing ships: piracy and mutiny. Both happened to ships carrying slaves for Woolfolk. The mutiny happened on April 20, 1826, when the schooner Decatur left for New Orleans with thirty-one enslaved people on board. When the veteran captain made the mistake of allowing small groups of them on deck unchained, two men took him by surprise and threw him overboard. The mate, attempting to come to his aid, was also thrown overboard. The mutineers had hoped to escape to “San Domingo” (Haiti, which since 1822 had taken over the entire island of La Española), but lacking navigation skills, they instead floated aimlessly and were overtaken.26

Ultimately fourteen men from the Decatur were brought into New York, where, incredibly, they escaped into the city. Only one man, William Bowser, was apprehended, and he alone was tried for the murders of the captain and the mate.

Coffles came via the National Road to Wheeling, Virginia, all the time during coffle season, there to be sent down the Ohio River, which empties into the Mississippi. Recalling his days as a nineteen-year-old saddler in Wheeling, Benjamin Lundy wrote, “My heart was deeply grieved at the gross abomination. I heard the wail of the captive; I felt his pang of distress; and the iron entered my soul.”27

After resettling a few miles away to raise his family on the other side of the borderline of emancipated Ohio, Lundy began an antislavery society and, in 1821, moved it to eastern Tennessee, where a manumission society existed. He took over a faltering antislavery publication, renamed it Genius of Universal Emancipation, and made it the first substantial antislavery publication in the United States. By 1824 he was publishing in Baltimore and traveling extensively. He wasn’t only a propagandist, but also an organizer, helping found other antislavery societies. He traveled to Haiti in 1825—still thirty-seven years away from being recognized by the United States—to make an arrangement with the Haitian government to take emancipated people. When in 1826 he arranged for the American Convention for the Abolition of Slavery to be held in Baltimore, there were “directly or indirectly, eighty-one societies” represented, “seventy-three being located in slaveholding States.”28

Lundy began hammering at Woolfolk in print. He reprinted the New York Christian Inquirer’s account of William Bowser’s trial and execution:

One woman, [Bowser] said, who was confined in Woolfolk’s prison, first cut the throat of her child, and then her own, rather than be carried away! … he was carried to the place of execution, when a few minutes before his exit he addressed the spectators in a few words, stating his willingness to die, and exhorting them to take warning by him to prepare to meet their God. As Woolfolk was present, he particularly addressed his discourse to him, saying he could forgive him all the injuries he had done him, and hoped they might meet in Heaven; but this unfeeling “soulseller,” with a brutality which becomes his business, told him with an oath, (not to be named,) “that he was now going to have, what he deserved, and he was glad of it,” or words to this effect! He would have probably continued his abusive language to this unfortunate man, had he not been stopped by some of the spectators who were shocked at his unfeeling, profane and brutal conduct. In a few moments after this, the unfortunate man was launched into eternity.29

Lundy ended his peroration with the words, “Hereafter let no man speak of the humanity of Woolfolk.”

In the South, such an insult against a gentleman would demand satisfaction in a duel, but Woolfolk did not pretend to be a gentleman, nor did he consider Lundy to be one. A few days after the article ran, Lundy was, as he put it in his memoir, “assaulted and nearly killed” when Woolfolk caught up with him on the street in Baltimore on January 9, 1827.30 Woolfolk beat Lundy severely, stomping on his head and leaving his face “in a gore of blood” that left him with a long recuperation and permanent damage. According to the coverage in Niles’ Weekly Register,* when Woolfolk was tried for the assault on Lundy, he denied having been in New York during the execution, but admitted

that he was guilty of a breach of the law, but in mitigation of the penalty they read several articles in the Genius of Universal Emancipation, which Lundy acknowledged he had written and published, in which the domestic slave trade from Maryland to the southern states was spoken of in the heaviest and bitterest terms of denunciation, as barbarous, inhuman and unchristian; and Woolfolk was called a “slave trader,” “a soul seller,” &c., and equally guilty in the sight of God with the man who was engaged in the African slave trade….

Chief justice Brice, in pronouncing sentence, took occasion to observe, that he had never seen a case in which the provocation for a battery was greater than the present—that if abusive language could ever be a justification for a battery, this was that case—that the traverser was engaged in a trade sanctioned by the laws of Maryland, and that Lundy had no right to reproach him in such abusive language for carrying on a lawful trade—that the trade itself was beneficial to the state, as it removed a great many rogues and vagabonds who were a nuisance in the state—that Lundy had received no more than a merited chastisement for his abuse of the traverser, and but for the strict letter of the law, the court would not fine Woolfolk any thing. The court however was obliged to fine him something, and they therefore fined him one dollar and costs.31

Woolfolk won the battle but lost the war; this violent clash of slave trader versus abolitionist was a propaganda victory for the burgeoning antislavery campaign, which in its early stages tactically consisted largely of attempts to prohibit the interstate slave trade.

It was not surprising that Lundy should receive street justice at the hands of a crude man like Woolfolk; physical threats and intimidation were a regular part of the arsenal of defending slavery. But Lundy’s protégé, William Lloyd Garrison, had the effrontery to call out the respectable merchant Francis Todd—from Garrison’s hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts—in the Genius of Universal Emancipation issue of November 13, 1829. Todd had allowed his vessel to be used to take eighty or so enslaved people from Herring Bay in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, down to New Orleans at the behest of a Louisiana planter who had purchased an entire plantation’s worth of labor.

Garrison, who was only beginning his career, was not impressed that, according to Todd’s testimony, the whole gang boarded cheerfully at the thought of being transported South to work together rather than to be broken up and sold separately; he wrote that Todd should be “SENTENCED TO SOLITARY CONFINEMENT FOR LIFE.”32 Todd sued him for libel, and Garrison was jailed for inability to pay approximately one hundred dollars in fine and costs after his conviction; ultimately, he was ransomed by a wealthy abolitionist. From his incarceration (which he was allowed to pass under conditions more like house arrest), he wrote a letter to Todd, printed in the Boston Courier:

How could you suffer your noble ship to be freighted with the wretched victims of slavery? … Suppose you and your family were seized on execution, and sold at public auction: a New-Orleans planter buys your children—a Georgian, your wife—a South Carolinian, yourself: would one of your townsmen (believing the job to be a profitable one) be blameless for transporting you all thither, though familiar with all these afflicting circumstances?33

Garrison went on to publish The Liberator, which began on January 1, 1831, and he formed the New England Anti-Slavery Society one year later to the day. The most consistently outspoken voice of the movement, The Liberator continued for thirty-five years, during which it focused on the slave trade as emblematic of the evils of slavery, and as slavery’s most vulnerable point. Local and state antislavery societies appeared, with the National Antislavery Society being formed in Philadelphia in late 1833.34

Abolitionism already had a decades-long history in Britain, going back to the days of the Somerset decision. Nicholas Biddle derided its presence in America as part of “the latest English fashions of philanthropy and dress.”35 Abolitionism was a much more radical position than merely being antislavery. One could be antislavery without actually intending to do anything about it, while barring free blacks from one’s state and letting the South continue having slaves. Abolitionists, who were both black and white, and both male and female, wanted slavery extinguished, immediately, where it existed—converted to free labor, without compensation for the slaveowners. As such, abolitionism was a revolutionary ideology. If implemented, it would have had the effect of impoverishing many of the richest men in the United States, devaluing their capital suddenly to zero. It would destroy the basis of Southern credit.

Even John Quincy Adams, who as a congressman delivered up sheaves of abolition petitions to the House of Representatives, wrote in his diary after spending an afternoon with Lundy:

Lundy … and the abolitionists generally are constantly urging me to indiscreet movements, which would ruin me and weaken and not strengthen their cause. My own family, on the other hand—that is, my wife and son and Mary—exercise all the influence they possess to restrain and divert me from all connection with the abolitionists and with their cause. Between these adverse impulses my mind is agitated almost to distraction. The public mind in my own district and State is convulsed between the slavery and abolition questions, and I walk on the edge of a precipice in every step that I take.36

Bona fide abolitionists were relatively few among the white population in the early days of the movement, though their numbers grew in the 1850s. The hard core of abolitionists, of course, were the enslaved themselves, along with free people of color, who constituted most of the first five hundred subscribers to The Liberator.37

During the summer of 1822, the city of Charleston was convulsed by the investigation of an alleged conspiracy headed by Denmark Vesey, an ex-sailor and free man of color who had cofounded Charleston’s African Methodist Episcopal church, where he was known as a radical abolitionist preacher.38

Vesey, whose first name came from his origin (if not his birthplace, which is unknown) on the Danish Caribbean island of St. Thomas, came with a suspect background: he had been enslaved in Saint-Domingue for a time as a boy.39 In South Carolina, he purchased his freedom from the sea captain Joseph Vesey with lottery winnings in 1799.40 Vesey was alleged to have organized a plot, said to be French-influenced, to kill white people, supposedly on Bastille Day, and flee for Haiti. Scholars have argued as to whether the conspiracy actually existed—many now believe it did not—or whether it was only in the imagination of Charleston mayor James Hamilton Jr., who made political hay out of it along with Robert J. Turnbull and Robert Y. Hayne, all of whom would in a few years become known as Nullifiers. But whether there was a conspiracy or not, the repression of a known revolutionary and the destruction of the “African Church”—the AME, affiliated with Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel—was real. One hundred thirty-five men were tried, and Vesey, sentenced to death on June 29, was one of thirty-five who were hanged, becoming a martyr. The AME church was burned by a mob, and its ministry exiled.*

Among the condemned was the African-born Jack Pritchard, or “Gullah Jack,” a conjurer who was part of the AME congregation and who was alleged to have been Vesey’s recruiter.41 African power objects were seen as part of the alleged plot’s military process, as expressed by South Carolina magistrate L. H. Kennedy’s reference to “powers of darkness” in pronouncing sentence on Pritchard on July 9:

In the prosecution of your wicked designs, you were not satisfied with resorting to natural and ordinary means, but endeavoured to enlist on your behalf, all the powers of darkness, and employed for that purpose, the most disgusting mummery and superstition. You represented yourself as invulnerable; that you could neither be taken nor destroyed, and all who fought under your banners would be invincible.42

Advertisement in the Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, October 22, 1822.

When the brig Sally carried twenty-five slaves from Charleston to Mobile on February 12, 1823, the manifest noted that they “were cleared of [involvement in] the recently attempted insurrection in Charleston.”43 The Vesey conspiracy provoked a series of retaliatory measures that included the formation of a new repressive organization, the South Carolina Association. The Negro Seamen’s Act provided for imprisoning free black sailors while their ships were docked in Charleston; in open defiance of federal law, it put South Carolina in the provocative position of detaining black British sailors. All emancipation petitions were to be denied; the entry of free people of color into the state was prohibited, as was all education for free or enslaved blacks. A kind of security fence bearing a medieval name became popular in Charleston: the chevaux-de-frise.

David Walker was probably in Charleston when the post-Vesey repression began. If Vesey had a plot, he might have been part of it. Walker, the first militant African American writer, was born with free status (free mother, enslaved father), probably in Wilmington, North Carolina (though there is no documentation), probably in 1796 or ’97, and he became literate, probably through Biblical education in the African Methodist Episcopal church in Wilmington.44 When he was grown, he moved to Charleston, where a small community of free blacks worked as craftsmen and entrepreneurs. An evangelical Christian, he probably attended the same AME church as Vesey and Gullah Jack. He moved on to less repressive Boston, probably in 1825 or ’26, where he married. He kept a used-clothes store in Beacon Hill, where he sold second-hand sailors’ uniforms. He was a subscription agent for the short-lived Freedom’s Journal, the first African American newspaper; edited by Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm, it was outspokenly abolitionist and anticolonization.

A chevaux-de-frise at the Miles Brewton House on King Street, Charleston, June 2013.

In the tradition of that foundational genre of American literature, the insurrectionary pamphlet, Walker published Walker’s Appeal in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular and Very Expressly to Those of the United States of America in September 1830. It demanded the immediate overthrow of slavery.

Walker’s Appeal explicitly talked back to Jefferson. As the idea of “colonization” for free people of color—which meant, deporting people like David Walker—grew, the legacy of Jefferson’s philosophical racism in Notes on the State of Virginia was being, in Walker’s words, “swallowed by millions of whites,” adding that “unless we try to refute Mr. Jefferson’s arguments respecting us, we will only establish them.”45 But beyond calling for black responses to Jefferson, Walker’s treatise was a call to action for immediate self-emancipation:

in the two States of Georgia, and South Carolina, there are, perhaps, not much short of six or seven hundred thousand persons of colour; and if I was a gambling character, I would not be afraid to stake down upon the board FIVE CENTS against TEN, that there are in the single State of Virginia, five or six hundred thousand Coloured persons. Four hundred and fifty thousand of whom (let them be well equipt for war) I would put against every white person on the whole continent of America. (Why? why because I know that the Blacks, once they get involved in a war, had rather die than to live, they either kill or be killed.) The whites know this too, which make them quake and tremble.46

Walker smuggled quantities of his Appeal into the South, where anyone remotely connected with its circulation would be considered guilty of sedition. The first place the Appeal turned up was Walker’s old home town of Wilmington, where the North Carolina legislature responded by meeting in a secret session to enact a slew of repressive measures against slaves but especially against free people of color. By the time Walker was mysteriously found dead on his own doorstep on June 28, 1830, the state of Georgia had a price on his head: $10,000 alive, $1,000 dead. The rumor spread that he had been poisoned, but no autopsy was done and no one stepped forward to claim the reward.

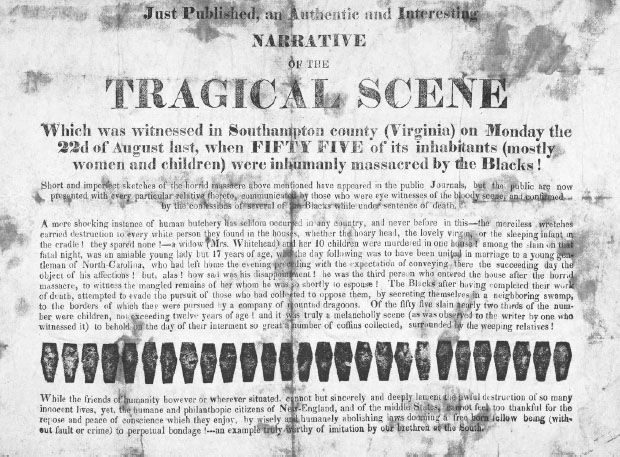

Walker’s Appeal was blamed by nervous Southerners for the bloody revolt in Virginia on August 21, 1831, when at least fifty-seven people were killed in an uprising at Southampton, a few miles inland from Norfolk. Led by the mystical evangelical preacher Nat Turner and four other enslaved men, the conspiracy had at least seventy followers. Turner was hanged on November 11, following which his dead body was skinned.

Reaction to Turner’s rebellion was swift. Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama all banned out-of-state traders for a time, though state residents could still bring slaves in, and could still sell them. The fear that Turner’s collaborators might show up in their territory corresponded to a frequently expressed belief in the Deep South, not entirely unfounded but certainly exaggerated, that the interstate slave trade was bringing in “the dregs of the colored population of the states north of us,” in the words of a correspondent to a Georgia newspaper.47 Louisiana’s prohibition lasted until 1834, when the immediate terror had passed and planters would wait no longer. Mississippi’s new constitution, to take effect in 1833, included a ban on slaves introduced “as merchandize.” There was an immediate outcry in Mississippi to lift the ban, and though it remained on the books, it was unenforced. The Mississippi legislature imposed a 2½ percent tax on slave sales, subsequently reduced to 1 percent. Mississippi’s flourishing slave trade was thus unconstitutional but not illegal, and it continued in a gray era until the state again prohibited importations in 1837.*

Excerpt from a broadside headlined Horrid Massacre in Virginia, 1831.

In Maryland, where much of the state no longer used slave labor, the reaction to the Turner uprising was to prohibit almost entirely the growing trend of manumission in 1832. At the same time, Maryland’s traffic to Louisiana, which had been drawing down the numbers of enslaved people in the state, stopped. These two reactions, writes Calderhead, “practically ended Maryland’s chances of eventually becoming a free state.”48

Nat Turner’s vision was apocalyptic, but most of the enslaved were more pragmatic. Africans had believed they would return home after death; African Americans were home, in a high-security prison on perpetual lockdown. There was no place for most of the enslaved to escape to—no occupying armies to defect to as in 1775 and 1814, no foreign-held territory in Florida, no Indians left to hide out with.

In Virginia, where many whites were already alarmed by having so many black people in their midst, the result of Turner’s rebellion was the debate of 1831–32 on the abolition of slavery, the only such debate in a Southern legislature ever. Among the many quotable statements of the session was the disapproving declaration by Charlottesville’s representative Thomas Jefferson Randolph, grandson of the recently deceased ex-president: “It is a practice, and an increasing practice, in parts of Virginia, to rear slaves for market.”49

Some individual slaveowners voluntarily impoverished themselves by freeing their slaves in the wake of the Turner rebellion. But after considering the matter, Virginia legislators unsurprisingly declined abolition, passing instead a repressive new slave code.

Thomas Dew, a respected academic who subsequently became the president of William and Mary College, published his much-read A Review of the Debate in the Virginia Legislature of 1831 and 1832 in Richmond. In it, he argued that ending slavery would reward Turner’s violence and legitimize the massacre. John Quincy Adams called Dew’s 140-page landmark pro-slavery work “a monument of the intellectual perversion produced by the existence of slavery in a free community.”50 A full discussion of Dew’s argument, which cites classical, Biblical, and European authors, is beyond the scope of our work, but we note two points:

1) Estimating the annual outflow of slaves into the Deep South market, Dew approvingly spoke of the fecundity of the capitalized womb as an economic engine for the state, affirming that “Virginia is in fact a negro raising state for other states; she produces enough for her own supply and six thousand for sale.” (emphasis in original) He was if anything conservative in his figure of six thousand annually exported; Frederic Bancroft believed the number might be double that, and some estimates are higher.51

2) He reported that the post-Turner legislation was actually good for business, with more Louisiana and Mississippi planters journeying up to buy slaves in Virginia in the absence of a mechanism for importing:

The Southampton massacre produced great excitement and apprehension throughout the slave-holding states, and two of them, hitherto the largest purchasers of Virginia slaves, have interdicted their introduction under severe penalties. Many in our state looked forward to an immediate fall in the price of slaves from this cause—and what has been the result? Why, wonderful to relate, Virginia slaves are now higher than they have been for many years past—and this rise in price has no doubt been occasioned by the number of southern purchasers who have visited our state, under the belief that Virginians had been frightened into a determination to get clear of their slaves at all events; “and from an artificial demand in the slave purchasing states, caused by an apprehension on the part of the farmers in those states, that the regular supply of slaves would speedily be discontinued by the operation of their non-importation regulations;” and we are, consequently, at this moment exporting slaves more rapidly, through the operation of the internal slave trade, than for many years past.52 (quotations in original, unsourced)

An inward manifest documenting the passage of six enslaved people from Charleston to New Orleans in 1832.

Even with Louisiana having closed its markets to outside traders from 1832 to 1834, there were still slaves coming into Louisiana, because New Orleans–based traders were still free to import, as per a manifest from September 24, 1832 (pictured), which shows the New Orleans trading firm Amidée Gardun et fils as “owners or shippers” of six people sent on the schooner Wild Cat from Charleston to New Orleans. One tries to imagine the stories behind the names and the descriptions by sex, age, height, and skin tone: Willis, Jack, Hector, Adam, Maria, and seven-year-old, three-foot-six Mary.

The business that Dew had enthusiastically described as “negro raising” was too important to stop. Meanwhile, Louisiana’s cutoff of importation, combined with the wild Jacksonian credit boom and the new availability of Mississippi land, stimulated the slave market at Natchez beyond anything previously experienced.

*Cycles of capitalism in the United States have been remarkably consistent: too much easy credit, followed by strain to the system resulting in the failure of key financial institutions, after which credit vanishes and the economy goes into a long tailspin.

*A widely read Baltimore magazine, edited by the antislavery Quaker Hezekiah Niles.

*The 1891 building of the Charleston A.M.E., “Mother Emanuel,” was the site of the 2015 Charleston Massacre of nine African Americans, including pastor and state senator Clementa Pinckney.

* The Groves v. Slaughter case, which went to the US Supreme Court in 1841, turned on the repudiation by a slave purchaser in Mississippi of a promissory note he had given a slave trader in payment by claiming that the state Constitution prohibited the sale. The Court ruled in favor of the trader.